Predicting functionality of protein–DNA interactions by integrating diverse evidence (original) (raw)

Abstract

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-chip) experiments enable capturing physical interactions between regulatory proteins and DNA in vivo. However, measurement of chromatin binding alone is not sufficient to detect regulatory interactions. A detected binding event may not be biologically relevant, or a known regulatory interaction might not be observed under the growth conditions tested so far. To correctly identify physical interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and genes and to determine their regulatory implications under various experimental conditions, we integrated ChIP-chip data with motif binding sites, nucleosome occupancy and mRNA expression datasets within a probabilistic framework. This framework was specifically tailored for the identification of functional and non-functional DNA binding events. Using this, we estimate that only 50% of condition-specific protein–DNA binding in budding yeast is functional. We further investigated the molecular factors determining the functionality of protein–DNA interactions under diverse growth conditions. Our analysis suggests that the functionality of binding is highly condition-specific and highly dependent on the presence of specific cofactors. Hence, the joint analysis of both, functional and non-functional DNA binding, may lend important new insights into transcriptional regulation.

Contact: workman@cbs.dtu.dk

1 INTRODUCTION

Regulation of transcription via the binding of specific proteins to DNA is the most important mechanism for controlling protein levels. Specific binding of transcription factors (TFs) controls the differentiation of progenitor cells into somatic cell types, it regulates the response to cellular stress and its misregulation is causal for many diseases such as cancer. Using technologies such as ChIP-chip, ChIP-seq or DamID, it is possible to measure the DNA binding of TFs at a genomic scale (Ren et al., 2000; van Steensel and Henikoff, 2000; Wei et al., 2006). These experiments, however, suffer from high levels of noise leading to the prediction of many false positive and false negative interactions (Beyer et al., 2006; Harbison et al., 2004). In addition, even if predicted binding is real, these experiments do not provide direct evidence about the downstream effects of the binding (Gao et al., 2004).

Indeed previous work has shown that DNA binding of transcription factors may have no effect on the transcription of proximal genes (Brockmann et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2004; Workman et al., 2006). However, the extent of non-functional binding (NFB) is still unknown. This lack of knowledge is also due to a methodological complication. It is relatively easy to predict functional binding (FB), because additional information such as the conservation of TF binding sites (TFBSs), expression changes of putative target genes and others can be used to corroborate the fact that an actual interaction between the TF and the promoter of the predicted target gene is functional. Thereby, the number of false positives can be greatly reduced (Beyer et al., 2006; Harbison et al., 2004). After such filtering procedure, one is left with TF–DNA interactions that were measured with e.g. ChIP-chip, but which have insufficient support from other data sources. These predicted bindings fall in one of two categories: (i) true binding that has no effect on the putative target gene and (ii) no real binding, i.e. false positive prediction, due to noise in the DNA binding experiment. Since it is difficult to disentangle these two classes, it is hard to estimate the extent of NFB.

Another equally important question is, given that physical binding to DNA takes place, what makes this binding event functional? Factors that may determine the functionality of TF–DNA binding are (i) distance of the binding site to the transcription start site (TSS), (ii) orientation of the TF with respect to the direction of transcription, (iii) local 3D structure of the DNA and (iv) presence or absence of interacting proteins (cofactors) in the same DNA region. Importantly, these factors have to be distinguished from other factors influencing the ability of a TF to bind a specific site per se, such as the presence of histones. Such competitive factors only affect the binding efficiency, but do not influence the functionality of the binding. Histone modifications on the other hand may affect both, the binding itself and its functionality. Usually it is not known which of the above factors control the functionality of a specific TF binding. Once it is possible to distinguish true binding events that are functional from those that are non-functional, we will also be able to investigate the molecular factors distinguishing one from the other.

In this study, we utilize Bayesian logic to first determine true physical binding events of budding yeast TFs and subsequently separate functional from NFB events based on respective expression data. Here, we define TF binding as functional if it has a specific effect on the transcript levels of its target gene (Gao et al., 2004). Since such downstream effect may be condition-specific, the statement ‘binding is functional’ always refers to a specific TF–target gene pair under a specific experimental condition. Therefore, we apply our analysis to a range of stress conditions.

We use condition-specific ChIP-chip data as the primary evidence for DNA binding, which we supplement with nucleosome occupancy and TFBS predictions. Once we have determined that TF–DNA binding depends on the change in growth condition, we use expression changes of putative target genes corresponding to the same conditions to determine functionality. In other words, we only assume that the binding was functional if differential binding correlates with differential expression changes under the same condition. Due to the noise in the data, we cannot reliably determine all true binding events under a certain condition. However, we can filter for a set of high confidence interactions and then ask, which fraction of those was functional. Hence, our probabilistic framework allows us to determine the fraction of true binding events that have no effect on the expression of proximal genes, i.e. the fraction of NFBs. Below, we show that this fraction is stable when changing the probability thresholds that our analysis requires.

Next, we employ the multi-parametric Random Forests machine learning technique to determine the factors controlling the functionality of TF binding. This analysis reveals that functionality is mainly determined by the presence of specific cofactors. Distance to the target gene and orientation of the TF also affect the functionality, but to a lesser extent. Importantly, we notice that functionality is determined in a highly combinatorial and hierarchical manner. Our analysis shows that the functionality of a first TF A may be affected by a second TF B, but B's functionality is independent of A. Hence, in this case B is a master regulator of A.

This work shows that the extent of NFB is considerable and analyzing both FB and NFB events provides important new insights into the functioning of transcriptional regulatory networks.

2 DATASETS

2.1 ChIP-chip

Protein–DNA binding for TFs of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been profiled under normal growth conditions (rich media, YPD) (Harbison et al., 2004; Iyer et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2002) as well as under different stress conditions (Harbison et al., 2004; Workman et al., 2006). We utilize ChIP-chip measurements of the genome-wide TF binding locations from the Harbison et al. (2004) study, which identified genome-wide binding locations for 203 TFs in YPD and 84 TFs in one or more stress conditions, and ChIP-chip data from Workman et al. (2006), which profiled 30 TFs after DNA damaging stress with methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). In this study, we compared protein–DNA binding profiles from YPD and six environmental stress conditions where mRNA expression responses to the same environmental conditions were also available (Gasch et al., 2000). In both cases, we made use of the binding _P_-values as calculated by the authors. ChIP-chip experiments employed for our analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Condition-specific binding data

| Condition | ChIP-chip | No. of TFs | Gene expression | No. of assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA starvation | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 34 | (Gasch et al., 2000) | 5 |

| Heat shock | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 6 | (Gasch et al., 2000) | 8 |

| H2O2 high | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 28 | (Gasch et al., 2000) | 9 |

| Galactose | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 4 | (Gasch et al., 2000) | 2 |

| Raffinose | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 1 | (Gasch et al., 2000) | 2 |

| MMS treatment | (Workman et al., 2006) | 30 | (Workman et al., 2006) | 4 |

| YPD | (Harbison et al., 2004) | 203 | – | – |

2.2 Gene expression data

Gene expression profiles measured under the six stress conditions relative to the expression in normal growth conditions (YPD) have been employed for our analysis (Gasch et al., 2000). Log ratios of gene expression from all existing replicates for each of the studied stress conditions are considered. In some cases, measurements taken at comparable time points after the treatment were regarded as replicates of the same experiment after an initial evaluation of the profile similarities and overall quality. These logratios were then used to calculate a _P_-value of differential expression of each gene and each stress condition using a _t_-test. In order to account for the small number of replicates, a _t_-test based on a moderated _t_-statistics (Smyth et al., 2005) was used. The moderated _t_-statistic uses a variance estimate over many genes, instead of a single gene, and has been shown to be more robust for small sample sizes (Smyth et al., 2005). Details of these gene expression studies can be found in Table 1.

2.3 TFBS data

Existing models of TF–DNA binding specificity, as represented by position-specific scoring matrices (PSSM) compiled in Beyer et al. (2006), were used to predict TFBSs (2006) for 111 TFs. A log-likelihood score distribution for each PSSM was determined using the sequence scoring feature of the ANN-Spec tool (Workman and Stormo, 2000) over all possible sites in the yeast genome. Using this empirical probability density function, we estimated _P_-values for each TFBS using the PSSM log-likelihood scores. In most cases, this allowed us to ensure that the expected rate of predicted binding site was <10−3. We identified all significant PSSM hits for the 111 TFs with a TFBS score smaller than the score/_P_-value threshold. TFBS hits occurring within 800 bp upstream and 200 bp downstream of a gene's start codon were considered as a potential promoter binding site for that gene. In the existence of multiple motif hits between a PSSM and a gene, the TFBS with the most significant score was considered as the primary TFBS hit. Binding site scores were then used in our Naive Bayes framework as supporting evidence for a physical interaction. Orientation of a TFBS and its distance from the start codon were later used as predictive variables to explain functionality of a TF–gene binding.

2.4 Nucleosome occupancy data

Nucleosome occupancy of DNA sequence around functional TFBSs has been shown to be remarkably lower (Daenen et al., 2008). Based on this, we employed Lee et al.'s (2007) experimentally obtained atlas of nucleosome occupancy to identify potential binding sites with low nucleosome occupancy. In this study (Lee et al., 2007), nucleosome binding was profiled using 25 bp probes spaced every 8 bp of both Watson and Crick strands of the complete genome sequence. For each base pair of the yeast genome, we averaged all measurements covering that base pair and generated a mean nucleosome occupancy map of the yeast genome. This map was then used to calculate an average occupancy score for each TFBS. The nucleosome occupancy of TFBSs is integrated with evidence from TFBS and ChIP-chip datasets in our Naive Bayes model.

2.5 Training and validation data

In order to fit and validate the various estimates used in this work, 1324 high-confidence regulatory interactions were obtained from the Incyte YPD Database, a curated, literature-derived data repository (http://www.incyte.com). These data represent much of the known regulatory interactions between TFs and genes of S.cerevisiae. In this context, these interactions have been used as a positive control set for calculating both the binding and the regulatory response probabilities. As the negative control dataset, we employed random TF–gene interactions, which were enhanced by a low co-citation criterion (Beyer et al., 2006).

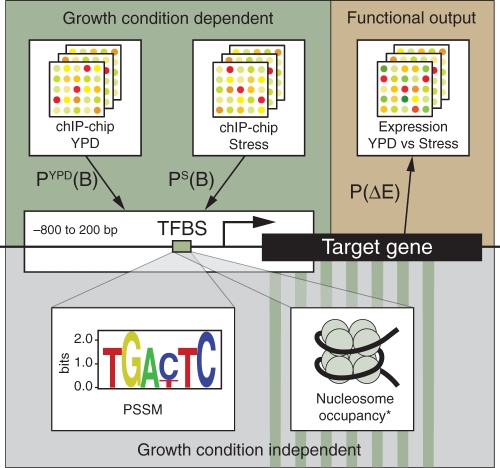

3 METHODOLOGY

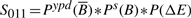

In order to reduce the number of false positive and false negative binding predictions, we integrated evidence from multiple sources to calculate the probability of a TF binding to a gene's promoter under an experimental condition c, P c(B) (Fig. 1). Importantly, we only use evidence for binding, i.e. at this step we exclude evidence such as expression data, which is predictive for the functionality of an interaction. ChIP-chip profiles generated under a particular experimental condition, TFBS data, and nucleosome occupancy of TFBSs are used as binding evidences. Using these datasets, a composite likelihood ratio of binding is calculated based on a Naive Bayes assumption regarding the conditional independence between these three predictive sources. Subsequently, the composite likelihood ratios are converted into posterior odds and finally into posterior probabilities by using a prior odds estimate that is derived from the statistics estimated using the validation data (Incyte YPD interactions). In summary, this step of our methodology aims to reliably predict binding of a regulatory protein to its targets under different experimental conditions.

Fig. 1.

The overall framework of the proposed methodology. *Though nucleosome occupancy is known to be condition dependent, it is treated as condition independent for this study.

We analyzed gene expression profiles along with these binding evidences to discriminate functional from NFB of a TF. A second probability, the probability of transcriptional response (P(Δ_E_)), to a change in growth condition was estimated, e.g. YPD to heat shock. This probability of functional response was calculated for each gene and for each stress condition based on the likelihood ratio obtained using Bayes' formula and the training datasets (Incyte YPD interactions).

We estimated binding probabilities in two different growth conditions, P _c_1(B) and P _c_2(B), as well as the response of the gene expression levels to this change in growth condition, from _c_1 to _c_2. As an example _c_1 can be a stress condition and _c_2 can be the normal growth conditions. These probabilities were further used to categorize TF–TG bindings as regulatory or non-regulatory binding or FB versus NFB. If a TF binds or is released from a gene's promoter only when the growth condition has changed, the gene's expression response to this environmental change can be used to determine the functional nature of the binding.

Next, we analyzed FB and NFBs to reveal biological factors that might play a causal role in the regulation. Distance of the binding site from the target gene, orientation of the binding site and binding of other TFs to the promoter region of the same gene were all considered as potential factors that might determine FB. We then used a feature selection algorithm based on Random Forests to identify the discriminatory factors for functionality of TFBS's and their corresponding TF–gene relationships. Our overall framework is summarized in Figure 1.

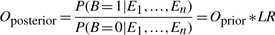

3.1 Probability of promoter binding

Posterior odds for the physical binding of a TF to its target gene's promoter (_O_posterior) can be calculated as the product of prior odds (_O_prior) and the likelihood ratio, LR. The prior odds quantifies the chance of interaction for a given TF–target pair when all pairs are considered and can be defined as P(_B_=1)/P(_B_=0), where P(_B_=1) is the probability of a physical interaction. Accordingly, the posterior odds that a TF–target pair constitutes a binding relationship given predictive evidence can be defined as:

|

(1) |

|---|

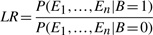

Here, E i represents the value of the TF–target pair for the _i_-th evidence and LR refers to the composite LR which can be defined as:

|

(2) |

|---|

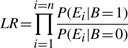

The problem with computing the likelihood ratio using the above equation is that it requires us to estimate many probabilities from limited training data. To overcome this issue, we assume that features (evidences) are conditionally independent of each other given the value of B. This assumption is often referred to as the independent feature model or as the Naive Bayes assumption. Accordingly, the simplified LR can be written as:

|

(3) |

|---|

The assumption of conditional independence, which is also the basis of Naive Bayes classification, may seem to be an oversimplification for many complex real world situations including the current one. However, as demonstrated by a number of studies, both empirical and theoretical, the performance of Naive Bayes Classifiers has been surprisingly good even in domains where this assumption is known to be a gross simplification (Domingos and Pazzani, 1996). Additionally, recent efforts have shown that Naive Bayes models can also be effective for probabilistic estimation and inference (Lowd and Domingos, 2005), suggesting that using such a model to estimate likelihood ratios like the one we describe may be reasonably effective.

Using the above Naive Bayes model, we integrated complementary evidence for protein–DNA binding from TFBS data (Workman and Stormo, 2000), nucleosome occupancy data (Lee et al., 2007) and ChIP-chip data (Harbison et al., 2004; Workman et al., 2006). Based on these three evidences, we are interested in computing the probability of binding in a particular condition for a given TF t and a gene g. ChIP-chip binding _P_-values provide evidence about physical interactions between t and g. Rank of a TFBS hit is another informative source in terms of existence of a real binding. Moreover, nucleosome occupancy of this TFBS also has an impact on TF binding. So, in our model, we separately derived likelihood ratios for the rank of the most significant TFBS hit between t and g, the corresponding average nucleosome occupancy of this TFBS and the _P_-value from the ChIP-chip data, i.e. _n_=3. These three likelihood ratios are then compiled into a single score of probability.

3.2 Probability of transcriptional response

Next, we calculated the probability of an expressional gene response based on the change of a gene's expression level in a stress condition relative to the normal growth condition. Here, we aim to assess the likelihood ratio of a gene being active (induced or repressed) under this stress condition relative to the unstressed situation. We again calculate the likelihood ratios using the positive and negative training dataset to derive the posterior probabilities. The likelihood ratio for responding is calculated based on the P_-values of the differential expression test (Δ_E). As previously discussed, these likelihood ratios were converted into posterior probabilities, where prior odds of an expression change is estimated from the Incyte YPD data (training data).

3.3 Characterization of binding events

We analyzed TF–target bindings under six stress conditions and the nominal growth condition. These binding probabilities were then used to identify condition-dependent changes in binding. Evidence for dynamic TF binding was then compared to the functional output of the putative regulatory events by analyzing the corresponding change in gene expression levels. Given this, one can tabulate the sample space for binding of a TF to its targets in two different conditions and the mRNA abundances compared between these two conditions as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Condition-dependent binding events

| _B_ypd | _B_stress | Δ_E_ | Semantics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | No binding | No response |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | No binding | Functional response |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | Differential binding | No response |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | Differential binding | Functional response |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | Differential binding | No response |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | Differential binding | Functional response |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | Constant binding | No response |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Constant binding | Functional response |

Here, we assume that a change in binding status accompanied by a change in expression can be considered as functional. Conversely, dynamic binding events with no change in the gene's transcript level can be viewed as non-functional. However, when binding is constant across two conditions, it is not easy to associate the functional response of the gene (or lack of response) to the binding event. This may be due to other factors or protein modifications that may modulate the regulatory activity even though the TF appears to remain bound both before and after stress. Therefore, we focused only on differential binding events. If differential binding to a promoter is observed in addition to a change in this gene's expression level (cases (B ypd, B stress, Δ_E_)={(0, 1, 1), (1, 0, 1)}), we labeled the corresponding binding as functional. On the other hand, if differential binding to a gene is observed but the gene's expression level is not significantly changing, then this is considered evidence of NFB (cases {(0, 1, 0), (1, 0, 0)}).

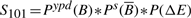

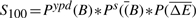

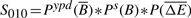

These definitions along with the previously defined probabilities allows us to rank TF–target bindings in terms of their functionality or non-functionality. We defined the four scores below to get the most functional and the most non-functional TF–target bindings.

- FB in YPD :

- FB in stress :

- NFB in YPD :

- NFB in stress :

Prior to score calculation, each of the probability distributions are equal-depth normalized (_P_-values based on ranks) separately to limit the impact of our prior estimates and the variability in the probability distributions range on the final scores. Based on these four scores, we can identify potential FB and NFBs between a TF and its target genes.

3.4 Determining factors that explain FB

Next, we aimed at determining factors that explain the difference between FB and NFB events of a given TF. We considered the following as potential factors:

- Distance: distance of the binding site with respect to the next start codon

- Orientation: binding orientation of the TFBS

- Cofactors: presence or absence of other TFs bound to the same promoter

The cofactor information is obtained from the previously calculated binding probabilities and therefore is limited by the number of TFs studied in that condition.

Since the factors are likely to act in parallel and in a combinatorial manner, we have employed multivariate methods for determining the individual importance of each factor. We have also tested univariate methods and the results are generally in agreement with the multivariate method (data not shown). However, since our multivariate approach includes factors that are known to influence gene regulation, e.g. co-transcription factors, we will focus on those results in this discussion.

The Random Forests classification method (Breiman, 2001) was used to determine features explaining the difference between FB and NFB either alone or in combination with other factors. Random Forests is an ensemble technique that combines individual classification trees into a forest of classification trees. Each individual tree is constructed from a bootstrap sample of the original samples and each splitting feature in the tree is chosen among a small random subset of original predictor variables. Random Forests are also shown to be effective in finding the predictor variables in a classification task. We employed an alternative implementation of Random Forests that eliminates the bias in variable selection where potential predictor variables vary in their scale of measurements and their number of categories (Strobl et al., 2007). Using this Random Forests algorithm, each variable is sorted according to its importance. The importance of each variable is calculated with the ‘permutation accuracy importance’ measure (Breiman, 2001).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Prediction of condition-specific promoter binding

We calculated binding probabilities based on three types of evidence under the normal growth condition (YPD) and the six stress conditions described in Table 1. In order to assess the predictive power of the binding probabilities, we first used them to predict known TF–target gene interactions from the Incyte YPD database by using a 5-fold cross-validation approach. For each TF–target pair, the posterior probabilities were calculated based on our Naive Bayes model.

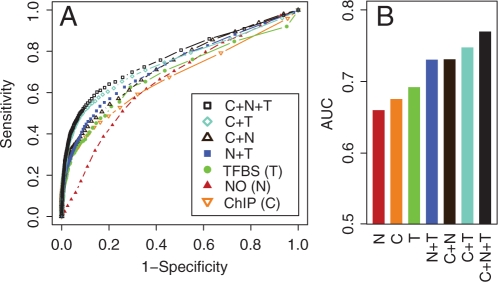

For varying posterior probability cutoffs, the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curves of our predictions were generated by using different combinations of the three types of evidence as shown in Figure 2. These ROC curves were generated based on ChIP-chip profiles measured under the YPD condition as it is the most comprehensive ChIP-chip source.

Fig. 2.

(A) ROC curves for TF–target predictions based on individual and integrated evidence, ChIP-Chip (ChIP, C), nucleosome occupancy (NO, N), transcription factor binding sites (TFBS, T) and combinations of them indicated with ‘+’, and (B) AUC scores generated by 5-fold cross-validation.

The figure indicates the anticipated result, i.e. that by combining these three sources in a model, we can better predict the existence of a physical interaction. When considering the area under the ROC curve (AUC) as a metric for predictive power, we observe an 11–17% improvement of the overall AUC score obtained by our integrated model (AUC=0.77) when compared to scores obtained by models based on single sources of evidences alone. By the ROC and AUC criteria, the predictive power of our posterior probabilities compares well to our previous work (Beyer et al., 2006) where a number of other weak lines of indirect evidence were integrated (so called ‘2hop’ relationships, data not shown).

It has been shown that nucleosome occupancy is remarkably lower around the functional TFBSs (Daenen et al., 2008) and that these data are useful for TFBS discovery (Narlikar et al., 2007). Here, we introduce a methodology to integrate this source with ChIP-chip data for predicting true DNA binding of TFs. Figure 2 shows that accounting for nucleosome occupancy at potential binding sites significantly improves the predictions. The complete list of our predictions of condition-specific TF bindings based on these three sources can be provided upon request.

4.2 Characterization of TFs and their promoter binding

Four scores are defined to quantify the functional status of TF–target bindings. For each stress condition, we labeled TF–target interactions that score >0.4 for scores _S_011 or _S_101 as FB events. Similarly, pairs that score above 0.4 for scores _S_010 or _S_100 were labeled as NFB events.

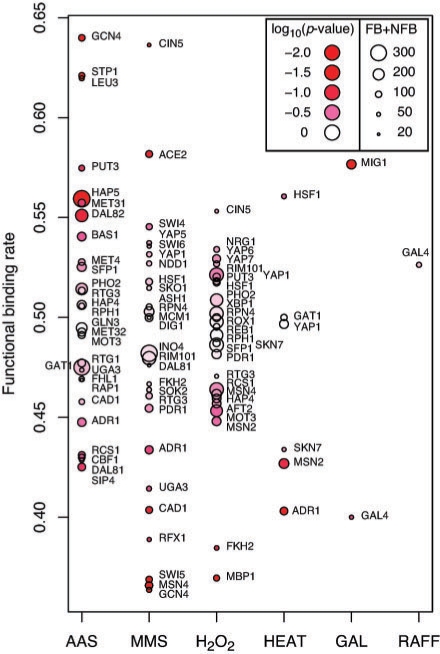

Based on these FB and NFB labels, for each TF and each stress condition we investigated the fraction of FB events. Given a condition and a specific TF, the ‘functional binding rate’ is the ratio of FB events compared to total differential binding (FB+NFB) for this TF–condition pair (i.e. FB/(FB+NFB)).

Figure 3 shows the FB rate for each TF-condition pair. The global FB rate was found to be 49% and did not significantly vary by stress condition. Although the overall distribution of FB rates varies considerably, standard deviation (SD) 0.06, this variation also did not appear to be condition specific (e.g. AAS SD=0.059, H2O2 SD=0.043 and MMS SD =0.067). The FB rates of individual TFs did depend on the threshold used though. More stringent thresholds (e.g. 0.5) resulted in more extreme FB rates due to the low numbers of predicted differential binding events, though FB rates were generally observed between 25% and 75%. In contrast, the global FB rate was remarkably stable (near 50%) over many different thresholds (0.4, 0.5 and 0.6) as can be seen in Table 3. It is also noteworthy that FB rates of individual TFs may be dramatically different for different conditions (Fig. 3). For example, GCN4's FB rate under amino acid starvation (AAS) is 64%, whereas it is just 36% after MMS treatment.

Fig. 3.

FB rates for individual TFs by condition. The size of point indicates the number of associated differential binding events predicted. Intensity of red indicates the significance of a χ2 test comparing the FB rate to the global mean FB rate (49.2% using the integrated threshold 0.4).

Table 3.

Mean FB rates by condition and threshold

| Threshold | AAS | MMS | H2O2 | HEAT | GAL | RAFF | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4 | 0.508 | 0.480 | 0.486 | 0.470 | 0.488 | 0.526 | 0.490 |

| 0.5 | 0.523 | 0.488 | 0.503 | 0.505 | 0.516 | 0.357 | 0.504 |

| 0.6 | 0.529 | 0.569 | 0.506 | 0.741 | 0.527 | 0.333 | 0.540 |

| TF number | 28 | 27 | 26 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 90 |

Each of the condition-specific FB rates was compared to the background FB rate (i.e. 49%) using a two-sided χ2 test. This analysis revealed that very few of the 90 TF–condition pairs generated FB rates significantly different from the expected rate though a few notable exceptions were found. In particular, the combination of GCN4 and AAS was found to be significantly enriched for FB events (unadjusted χ2 p<1_e_−2). Gcn4p factor is a well-known master regulator of amino acid metabolism, so this finding was not a surprise. The result does represent an important positive control and offers additional validation of our approach.

Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Ashburner et al., 2000) for the FB and NFB target gene sets were analyzed for the enrichment of assigned GO terms for each of the 90 TF–condition pairs using the GO Term Finder (Boyle et al., 2004). When we compare the total number of FB and NFB target sets that contained one or more significantly enriched GO terms (P<0.05), it was clear in the AAS and H2O2 conditions that more of the FB target sets contained enrichment of functional ontology terms (28 for FB versus 15 for NFB). In addition, the most significant results were observed for the FB target sets (data not show). The full interpretation of the significantly enriched terms is not clear and will require further analysis.

In summary, using our probabilistic method we find that roughly 50% of the condition-specific binding events are accompanied by differential expression of the targeted gene. Each of these FB observations verifies a gain or loss of positive regulation or a repression or de-repression event across the compared growth conditions. The 50% of NFB may arise for a number of reasons: (i) non-optimal distance of the TFBS to the TSS, (ii) incorrect orientation of the TFBS relative to the TSS and (iii) lack of the appropriate cofactors. In the next section, we explore the evidence for these possible determinants.

4.3 Exploration of predictive features for FB events

Next, we wanted to explain why certain TF binding events are functional whereas others are not. In order to answer this question, we focused on a selected set of interactions that were functional and non-functional with very high confidence. The top 1% of all pairs with the highest _S_101 and _S_011 scores were labeled as the FB events. Similarly the top 1% of all pairs with the highest _S_100 and _S_010 scores were selected as the NFB events. Next, we identified binding site features and cofactors explaining the difference between the two groups. We used the multivariate Random Forests method to calculate the importance of each feature for predicting the class response, in this case functionality of binding. To identify the significant predictors for each TF, we obtained a background distribution of this score by randomizing the response variable (FB/NFB). Subsequently, the variable importance scores were re-calculated for each variable. These randomization experiments were repeated 1000 times to get a stable background distribution of the variable importance scores. Finally, importance scores of each predictor were converted into _P_-values with respect to the empirical distribution obtained from the randomization experiments. Factors with _P_-values <0.05 were chosen as significant predictors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Significant predictors for functionality of TFs under studied conditions

| Condition | TF (cofactor instances) | Important factors for binding functionality | Condition | TF (cofactor instances) | Important factors for binding functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galactose | GAL4 (0) | Distance | AAS | MET31 (1) | DAL81,DAL82,GCN4,GLN3,HAP5,RAP1 |

| AAS | MET4 (5) | RCS1,RTG1 | |||

| Heat shock | SKN7 (0) | MSN2 | AAS | MOT3 (2) | DAL82 |

| AAS | PHO2 (0) | GCN4,GLN3,HAP4,MET31 | |||

| MMS treatment | ADR1 (0) | Orientation | AAS | RPH1 (1) | DAL81,MET4,UGA3 |

| MMS treatment | ASH1 (1) | RIM101 | AAS | RAP1 (2) | GAT1,RAP1 |

| MMS treatment | CAD1 (3) | FKH2,DAL81 | AAS | RTG1 (2) | BAS1 |

| MMS treatment | CIN5 (0) | Distance, MCM1 | AAS | RTG3 (2) | GCN4,HAP5,MET4,SFP1 |

| MMS treatment | DIG1 (2) | RFX1,SKO1 | AAS | SFP1 (4) | Orientation,MET4,PUT3,RAP1 |

| MMS treatment | FKH2 (1) | DAL81, MCM1, RTG3 | AAS | SIP4 (0) | SFP1 |

| MMS treatment | GCN4 (1) | YAP5 | AAS | STP1 (1) | GCN4,RTG1 |

| MMS treatment | HSF1 (0) | DAL81,RPN4 | AAS | UGA3 (3) | BAS1,RCS1,RTG3 |

| MMS treatment | INO4 (2) | ASH1,CAD1,INO4,MCM1 | |||

| MMS treatment | MSN4 (1) | DIG1 | H2O2 | AFT2 (0) | CIN5, YAP7 |

| MMS treatment | NDD1 (1) | YAP5 | H2O2 | CIN5 (2) | HSF1,PHO2 |

| MMS treatment | RFX1 (0) | INO4 | H2O2 | FKH2 (2) | XBP1 |

| MMS treatment | RTG3 (1) | DIG1 | H2O2 | HAP4 (1) | MSN4,PHO2,PUT3,YAP6 |

| MMS treatment | SOK2 (0) | CAD1, UGA3 | H2O2 | HSF1 (1) | Orientation,FKH2,RIM101,SFP1 |

| MMS treatment | SWI4 (0) | PDR1,SKO1 | H2O2 | MBP1 (1) | MOT3,MSN2,REB1,SKN7 |

| MMS treatment | SWI5 (0) | CAD1 | H2O2 | MOT3 (1) | MSN2,MSN4 |

| MMS treatment | SWI6 (0) | MCM1,MSN4,RIM101 | H2O2 | MSN2 (2) | MSN4,PUT3,RCS1 |

| MMS treatment | YAP1 (0) | GCN4,NDD1 | H2O2 | MSN4 (5) | SFP1 |

| H2O2 | PDR1 (0) | SFP1,SKN7 | |||

| AAS | ADR1 (1) | RPH1,MET4,SFP1 | H2O2 | PHO2 (5) | FKH2,SKN7,XBP1 |

| AAS | BAS1 (4) | CBF1,STP1,UGA3 | H2O2 | REB1 (2) | HAP4 |

| AAS | CBF1 (2) | BAS1,GCN4,HAP5,MET4 | H2O2 | RIM101 (1) | YAP1 |

| AAS | DAL81 (2) | Distance,CBF1 | H2O2 | ROX1 (0) | MSN4,RTG3,SFP1 |

| AAS | DAL82 (4) | GCN4,PUT3 | H2O2 | RPH1 (2) | Distance,PHO2 |

| AAS | FHL1 (0) | DAL82 | H2O2 | RPN4 (0) | Distance |

| AAS | GAT1 (1) | ADR1 | H2O2 | RTG3 (1) | NRG1 |

| AAS | GCN4 (8) | GLN3,MET32 | H2O2 | SFP1 (5) | Orientation,MSN4,RPH1 |

| AAS | GLN3 (3) | GCN4,MOT3,PUT3,SFP1 | H2O2 | SKN7 (3) | CIN5,MBP1 |

| AAS | HAP4 (1) | MOT3,RTG3 | H2O2 | YAP6 (3) | RPH1 |

| AAS | HAP5 (3) | BAS1,DAL82,GCN4 | H2O2 | YAP7 (1) | PHO2,REB1,YAP6 |

| AAS | LEU3 (0) | CBF1,UGA3 | H2O2 | XBP1 (2) | PHO2,SFP1,YAP6 |

These factors can be very useful in understanding functionality of TF binding. In some cases, for example, the geometry of a binding site (distance to gene, orientation) can be very important for the regulatory implications of a physical interaction. For example, for CIN5 in the MMS stress condition, an incorrect distance of the TFBS can lead to NFB. However, in most cases binding of other TFs to the gene's promoter region determines the functionality of binding. The most extreme example is MET31 under AAS. In this case, our algorithm predicts that its functionality of binding depends on six other TFs. As can be seen from Table 4, GCN4 is clearly the most important cofactor for the AAS condition. In this condition, we found that the functionality of 8 out of 24 tested regulators depended on the binding of GCN4. This finding recapitulates well established knowledge about GCN4's role in AAS. GCN4 is known to regulate most genes responding to this stress and it is known to be the first level responder (Hinnebusch, 2005). In the case of H2O2 treatment, PHO2 and MSN4 are identified as the most important cofactors for regulation in this condition.

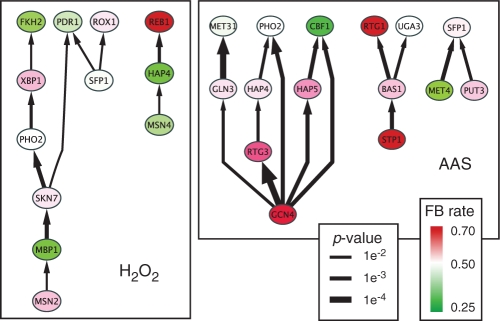

4.4 Identification of cofactor hierarchy networks

Using the cofactor relationships with significant _P_-values defined in the previous section, we identified larger systems of dependencies between regulatory proteins in each condition. As an example, functionality of eight TFs in the AAS condition is dependent on the binding of GCN4 to the same promoter region (P<0.05). On the other hand, GCN4's functionality appears to be dependent on only two cofactors (MET32 and GLN3) at this same threshold. Hence, this analysis establishes a hierarchy of regulatory relationships with GCN4 being the master regulator for responding to AAS. The set of significant dependencies can be used to define a hierarchical network describing the cofactors dependencies between TFs.

Examples of these significant relationships are shown for the AAS and H2O2 conditions for a more stringent variable importance threshold (P<0.01) in Figure 4. Given this set of the most significant cofactor dependencies, we can still clearly observe the ‘master regulator’ status of GCN4 in the AAS condition.

Fig. 4.

Significant TF–TF cofactor relationships as determined by the multivariate Random Forest method (P <0.01 by randomization trials) for the AAS and H2O2 stress conditions. This hierarchical network view shows TFs (nodes) and cofactor relationships (edges) where direction of dependency is indicated by the arrow. In this representation, _X_ ->Y implies that binding functionality of Y depends on X. The thickness of the edge indicates the significance of the X variable in determining functionality of Y binding. The node color indicates the FB rate of the TF in that condition, red indicates rates higher than expected while green indicates lower than expected rates.

The peroxide stress results also place MSN2 and MSN4 as being required as a cofactor for a cascade of regulators (Fig. 4). The importance of MSN2 and MSN4 are well documented in the oxidative stress response (Estruch and Carlson, 1993) and both are known to bind stress response elements (STRE) in response to a number of stress conditions. Though functional roles are known to be partially redundant, recent work also indicated distinct roles for MSN2 and MSN4 (Estruch, 2000) as is also suggested in Figure 4.

Figure 4 also shows the TF's FB rate (node color red/green for high/low FB rate) and it should be noted that this information does effect whether a significant cofactor relationship is likely to occur or not other than the case where all differential binding predictions are of only one category, FB or NFB. In these atypical cases, the FB versus NFB importance of other variables cannot be estimated. Based on these networks and the ones for other variable importance thresholds (data not shown), it is tempting to suggest that TFs at the top of the dependency hierarchies are more enriched for FB. Indeed this makes some intuitive sense. Dynamic binding events that require the fewest additional cofactors are the ones most likely to be functional.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We believe that the ability to distinguish functional from non-functional interactions within living cells is an important research area and will only increase in importance in the future. The need for methods to address this problem may already be acute considering the volume of protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions that have been systematically measured by yeast-two-hybrid, mass spectrometric, ChIP-chip, ChIP-Seq and other methods. The functional fraction of these newly determined and valid protein interactions is currently unclear. Our work strives to answer this question by exploiting dynamic protein–DNA binding events coupled with potential expression changes in the output of the corresponding regulatory system. The method described in this work gives a first estimate for the functionality of condition-dependent protein–DNA interactions and sheds light on the possible causal factors determining functionality.

Funding: Klaus Tschira Foundation (to A.B.); Danish National Research Foundation and the Simon Spies Foundation (to C.T.W.); National Science Foundation (NSF-CAREER-IIS-0347662, NSF-IIS-0742999) (to D.U. and S.P.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A, et al. Integrated assessment and prediction of transcription factor binding. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle EI, et al. GO:: TermFinder-open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann R, et al. Posttranscriptional expression regulation: what determines translation rates. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daenen F, et al. Low nucleosome occupancy is encoded around functional human transcription factor binding sites. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos P, Pazzani M. Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Machine Learning. Bari, Italy: Morgan Kaufmann; 1996. Beyond independence: Conditions for the optimality of the simple Bayesian classifier; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Estruch F. Stress-controlled transcription factors, stress-induced genes and stress tolerance in budding yeast. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000;24:469–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estruch F, Carlson M. Two homologous zinc finger genes identified by multicopy suppression in a SNF1 protein kinase mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:3872–3881. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, et al. Defining transcriptional networks through integrative modeling of mRNA expression and transcription factor binding data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, et al. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison CT, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. Transcriptional regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer VR, et al. Genomic binding sites of the yeast cell-cycle transcription factors SBF and MBF. Nature. 2001;409:533–538. doi: 10.1038/35054095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, et al. Transcriptional Regulatory Networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;298:799–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, et al. A high-resolution atlas of nucleosome occupancy in yeast. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1235–1244. doi: 10.1038/ng2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowd D, Domingos P. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning. Vol. 22. Bonn, Germany: ACM Press; 2005. Naive Bayes models for probability estimation; pp. 529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar L, et al. Nucleosome occupancy information improves de novo motif discovery. Lect. Note. Comput. Sci. 2007;4453:107. [Google Scholar]

- Ren B, et al. Genome-Wide Location and Function of DNA Binding Proteins. Science. 2000;290:2306–2309. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, et al. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. Limma: linear models for microarray data; pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Strobl C, et al. Bias in random forest variable importance measures: Illustrations, sources and a solution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B, Henikoff S. Identification of in vivo DNA targets of chromatin proteins using tethered Dam methyltransferase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:424–428. doi: 10.1038/74487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CL, et al. A global map of p53 transcription-factor binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2006;124:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman CT, et al. A systems approach to mapping DNA damage response pathways. Science. 2006;312:1054–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.1122088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman CT, Stormo G. ANN-Spec: a method for discovering transcription factor binding sites with improved specificity. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2000;5:464–475. doi: 10.1142/9789814447331_0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]