Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Beta Cells and Development of Diabetes (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Dec 1.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009 Aug 6;9(6):763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.07.003

Abstract

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a cellular compartment responsible for multiple important cellular functions including the biosynthesis and folding of newly synthesized proteins destined for secretion, such as insulin. A myriad of pathological and physiological factors perturb ER function and cause dysregulation of ER homeostasis, leading to ER stress. ER stress elicits a signaling cascade to mitigate stress, the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). As long as the UPR can relieve stress, cells can produce the proper amount of proteins and maintain ER homeostasis. If the UPR, however, fails to maintain ER homeostasis, cells will undergo apoptosis. Activation of the UPR is critical to the survival of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells with high secretory protein production. Any disruption of ER homeostasis in β-cells can lead to cell death and contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetes. There are several models of ER stress-mediated diabetes. In this review, we outline the underlying molecular mechanisms of ER stress-mediated β-cell dysfunction and death during the progression of diabetes.

Introduction

Proteins form the basic building blocks of cells, tissues, enzymes, and organs. Continuous production of proteins and selective degradation of defective or excessive proteins are essential processes for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and for the regulation of cell function. Newly produced proteins are not immediately functional. To become functional, they must fold into their proper three-dimensional structures. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) has an essential function in the protein folding process for secretory proteins, such as insulin, as well as cell surface receptors and integral membrane protein.

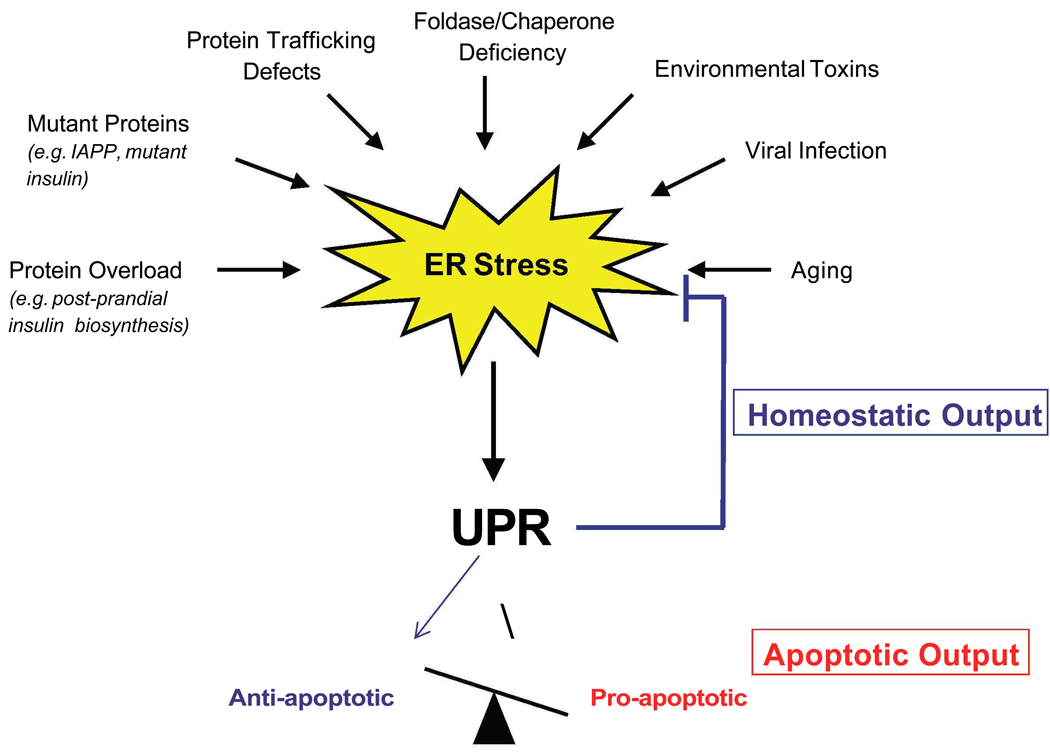

Protein folding in the ER is essential to cell survival, and is preserved during evolution in both unicellular organisms and eukaryotes. But as secretion is the basis of multicellularity, ER protein folding homeostasis powerfully impacts the physiology of higher eukaryotes. The sensitive folding environment in the ER can be perturbed by pathological insults such as viral infections, environmental toxins, inflammatory cytokines, and mutant protein expression, as well as by physiological processes such as aging and the large biosynthetic load placed on the ER due to insulin production in response to food uptake (Figure 1). When the demand that a load of proteins places on the ER exceeds its folding capacity, the result is ER stress.

Figure 1. ER stress.

There are several causes of ER stress, including protein overload. ER stress activates the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), which has two outputs: 1) homeostatic (blue) and 2) apoptotic (red). The homeostatic output leads to resolution of ER stress, while the apoptotic output, resulting from an insufficient UPR, favors the activation of pro-apoptotic over anti-apoptotic UPR

The cytoprotective, adaptive response to ER stress is the unfolded protein response (UPR), also called ER stress signaling (Figure 2). As long as the UPR can mitigate ER stress, cells maintain protein homeostasis and generate protein relative to the need for it. Under these conditions, ER stress is beneficial. There are four distinct responses of the UPR: 1) up-regulation of molecular chaperones to increase the folding activity and reduce protein aggregation, 2) translational attenuation to reduce ER workload and prevent further accumulation of unfolded proteins, 3) ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) to promote clearance of unfolded proteins, and 4) apoptosis when function is extensively impaired [1,2]. The UPR must maintain a balance between its downstream targets, which are anti-apoptotic and those which are pro-apoptotic (Figure 1). When the cell encounters ER stress and the UPR is properly balanced, the cell is then primed for a future insult. However, when activation is tipped in the favor of pro-apoptotic components due to UPR dysfunction or chronic and high ER stress, the cell undergoes irreversible damage which leads to cell death.

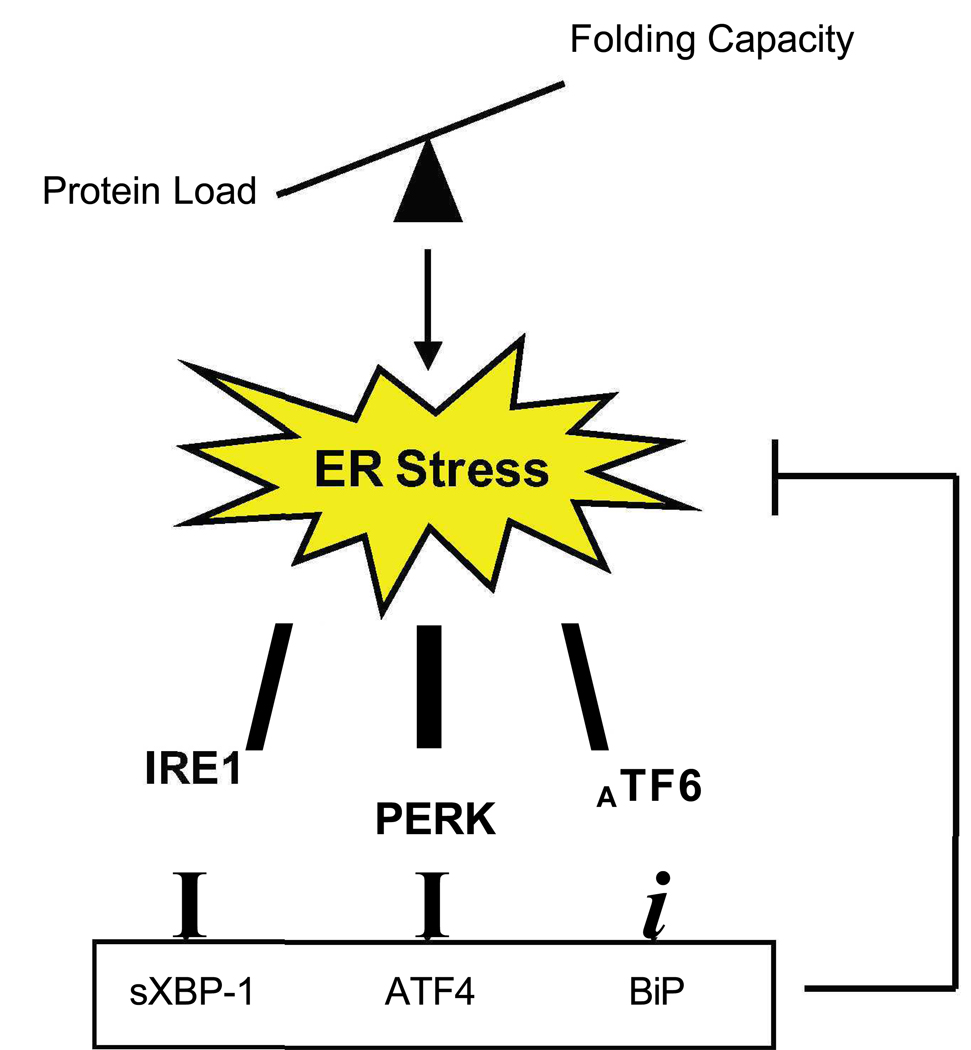

Figure 2. ER stress signaling networks.

There are three main regulators of the UPR: IRE1, PERK, and ATF6. Each of these transducers activate downstream targets which in turn mitigate stress.

ER stress signaling network

There are three master regulators of this signaling pathway: inositol requiring 1 (IRE1), PKR-like kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Figure 2). The signaling from downstream effectors of these pathways merges in the nucleus to activate UPR target gene transcription.

IRE1, a central regulator of the UPR, is a type I ER transmembrane kinase. Its N-terminal luminal domain acts as a sensor for ER stress signaling [3]. Upon sensing the presence of unfolded or misfolded proteins, IRE1 dimerizes and autophosphorylates to become active. Activated IRE1 splices X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA [4–6]. Spliced XBP1 mRNA encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor that upregulates UPR target genes, including genes that function in ERAD such as ER-degradation-enhancing-α-mannidose-like protein (EDEM) [7], as well as genes that code for folding proteins such as protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) [8]. High levels of chronic stress lead to the recruitment of TNF-receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) by IRE1 and the activation of apoptosis-signaling-kinase 1 (ASK1). Activated ASK1 activates c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) and leads to apoptosis [9–11].

PERK, a second regulator of the UPR, is responsible for regulating protein synthesis during ER stress [12,13]. It, too, is a type I ER transmembrane kinase. Like IRE1, its N-terminal luminal domain is sensitive to ER stress. When activated by ER stress, PERK oligomerizes, autophosphorylates and then directly phosphorylates Ser51 on the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α) [12]. This in turn inhibits protein translation by reducing the formation of ribosomal initiation complexes and recognition of AUG initiation codons. This leads to a reduction in ER workload and protects cells from ER stress-mediated apoptosis [13]. Concomitant with the inhibition of general translation is the increased selective translation of UPR target genes, as these polycistronic mRNAs have inhibitory upstream open reading frames (uORFs) and are thus preferentially translated by the ribosome. One of these mRNAs is that of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), a b-ZIP transcription factor that regulates UPR targets such as C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) and growth arrest and DNA damage inducible gene 34 (GADD34), as well as genes involved in redox balance and amino acid synthesis [14].

A third regulator of ER stress signaling and mediator of transcriptional induction, ATF6, is a type II ER transmembrane transcription factor [15]. Upon sensing stress in its N-terminal luminal domain, ATF6 transits to the Golgi where it is cleaved by S1 and S2 proteases, generating an activated b-ZIP factor [16]. This processed form of ATF6 translocates to the nucleus to activate UPR target genes responsible for protein folding and ERAD [17,18]. There are two isoforms of ATF6, ATF6α and ATF6β, with fairly ubiquitous tissue distribution. The α-isoform has been shown to be solely responsible for transcriptional induction of ER chaperones [19*]. It has been reported that unprocessed ATF6 is unstable and quickly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to prevent hyper-activation of the UPR [20].

The Diabetic Beta Cell

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by chronic high blood glucose levels. The two main forms of diabetes mellitus are type 1 and type 2 diabetes; they are characterized by an absolute or relative deficiency, respectively, in insulin production. This disease is associeted with severe peripheral effect and lead to heart disease, kidney failure, and blindness, thus it can be very devastating. The pathogenesis of this disease involves pancreatic β-cell dysfunction (i.e. insufficient insulin production). Recent evidence suggests that defective ER stress signaling contributes to β-cell dysfunction and eventual β-cell death. One main reason behind this is the highly specialized secretory function of β-cells to produce insulin in response to fluctuations in blood glucose levels. This constant demand from the body for insulin biosynthesis and secretion, has made β-cells dependent on a greatly efficient UPR. Indeed, baseline ER stress levels are high in these cells [21**].

Due to these observations, ER stress signaling is becoming more and more a focus in diabetes research. These efforts are supported by the recent identification of genetic links between ER stress and patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, a focus for this review.

Genetic Forms of ER Stress-Mediated Beta Cell Death

Wolcott-Rallison Syndrome

The relationship between ER stress and diabetes was first revealed in a rare autosomal recessive form of juvenile diabetes, Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. In 1972, Wolcott and Rallison described two brothers and a sister with infancy-onset diabetes mellitus and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia [22]. In this syndrome, mutations have been reported in the EIF2AK3 gene encoding PERK [23]. Because these mutations are within the catalytic domain of PERK, it is likely that they cause a loss-of-function of PERK kinase activity. This loss of PERK kinase activity leads to the reduction in the phosphorylation of eIF2α, a substrate of PERK. When a high workload is placed on the ER of the beta cell, for example when insulin demand increases following meal intake, phosphorylation of eIF2α is essential in mitigating ER stress and thereby promotes cell survival [14]. Therefore, a loss-of-function of PERK and a consequent disruption in translational attenuation during ER stress via decreased eIF2α phosphorylation, could directly attribute to beta cell apoptosis. This has been illustrated in several animal models. Indeed, PERK −/−mice develop diabetes due to excessive ER stress in their β-cells causing β-cell apoptosis [24]. Additionally, mutant mice carrying a heterozygous mutation in the phosphorylation site of eIF2α (Eif2s1+/tm1Rjk) become obese and, due to beta cell dysfunction, diabetic when fed a high-fat diet [25]. Collectively, these observations suggest that beta cell apoptosis in Wolcott-Rallison patients is caused by excessive, unresolved ER stress and a defect in the UPR (i.e. PERK signaling).

The negative regulator of PERK signaling, protein kinase inhibitor of 58 kDa (P58IPK), also functions in maintaining ER homeostasis in β-cells. P58IPK is an important component of a negative feedback loop used by these cells to inhibit eIF2α signaling and attenuate the UPR [26]. P58IPK knockout mice show a gradual onset of glucosuria and hyperglycemia associated with increased apoptosis of islet cells [27], thus this UPR component may be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes in humans.

Permanent Neonatal Diabetes

Permanent neonatal diabetes may also be attributed to excessive ER stress in the β-cell. Neonatal diabetes is defined as insulin-requiring hyperglycemia within the first month of life. This is typically associated with slowed intrauterine growth and is a rare disorder. Permanent neonatal diabetes, considered a genetic disorder, can be caused by several types of mutations, including mutations in insulin promoter factor 1 (IPF-1), and results in lifelong dependence on insulin injections. It has recently been shown that mutations in the human insulin gene, specifically mutations occurring in critical regions of preproinsulin can also cause this kind of pathology [28*]. This is an autosomal dominant disorder, with mutations primarily occurring in critical regions of preproinsulin. This presumably leads to improper folding of insulin, triggering the UPR and ultimately leads to β-cell apoptosis. A mouse model of this disease, the Munich and Akita mouse, has a dominant missense mutation in the Ins2 gene [29,30]. In the Munich mouse, there is a cysteine95-to-serine substitution, leading to a loss in an inter-chain disulphide bond of proinsulin [30]. In the Akita mouse, there is a cysteine96-to-tyrosine substitution [29]. This mutation also leads to disruption of disulphide formation between the A and B chain of proinsulin, causing insulin to misfold and accumulate in the ER of the β-cell [29]. This accumulation of misfolded insulin leads to severe ER stress, β-cell apoptosis, and consequently diabetes [31].

ER Stress in Type 1 Diabetes

Increasing evidence supports the role of ER stress-mediated β-cell death in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (i.e. autoimmune diabetes). The baseline of ER stress in β-cells is higher than that of other cell types due to their exposure to frequent energy fluctuations, as well as their high client load, insulin. It is therefore possible that any additional ER stress applied to these cells by genetic or environmental factors can lead to cell death. β-cells that undergo apoptosis as a consequence of this additional, unresolved ER stress contain misfolded proteins that can act as “neo-autoantigens” – dendritic cells in the islets engulf ER stress-induced apoptotic β-cells and stimulate the maturation of β-cell-reactive T cells that mediate autoimmune destruction of remaining β-cells [32]. Viral infections, environmental stresses, as well as nitric oxide (NO), are several insults to the β-cell that can lead to excessive, unresolved ER stress, triggering an apoptotic cascade and leading to the production of “neo-autoantigens”.

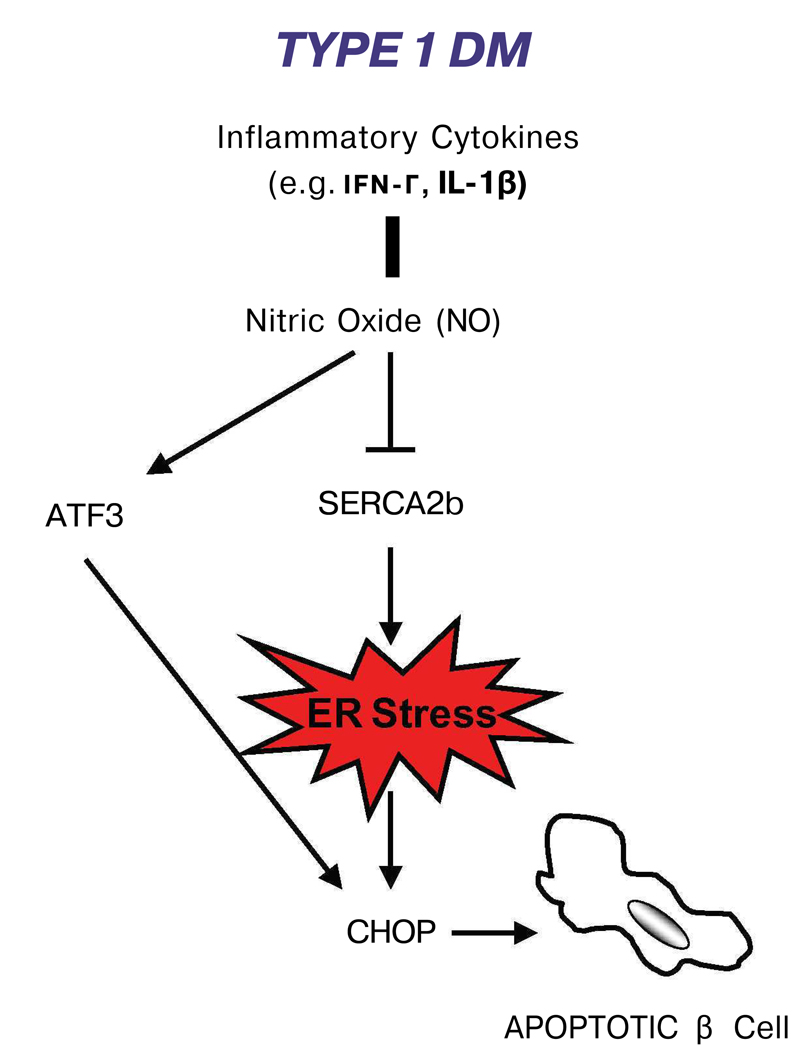

NO plays an important role in β-cell apoptosis in type 1 diabetes [33]. Inflammatory cytokines such as γ-interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in beta cells induce the production of NO, which leads to β-cell failure and consequently cell death. There is evidence that this process is mediated by ER stress [34]. Production of NO leads to the attenuation of the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase2b (SERCA2b) and consequently the reduction of calcium in the ER. This calcium depletion leads to severe ER stress and the induction of the pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP [35,36**]. It has been shown that CHOP is induced by a NO donor, S- nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (SNAP), and pancreatic islets from CHOP−/− mice are resistant to NO-induced apoptosis [34] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The role of ER stress in type 1 diabetes.

Exposure of β-cell to inflammatory cytokines leads to nitric oxide production, causing ER stress and activation of the UPR pro-apoptotic factor, CHOP.

Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a pro-apoptotic transcription factor of the ATF/CREB family, may also contribute to ER stress-mediated apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. ATF3 is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and NO (Figure 3). ATF3 knockout mouse islets are partially protected from NO- and cytokine-induced beta cell apoptosis, while over-expression of this transcription factor in mouse islets leads to β-cell dysfunction [37].

ER Stress in Type 2 Diabetes

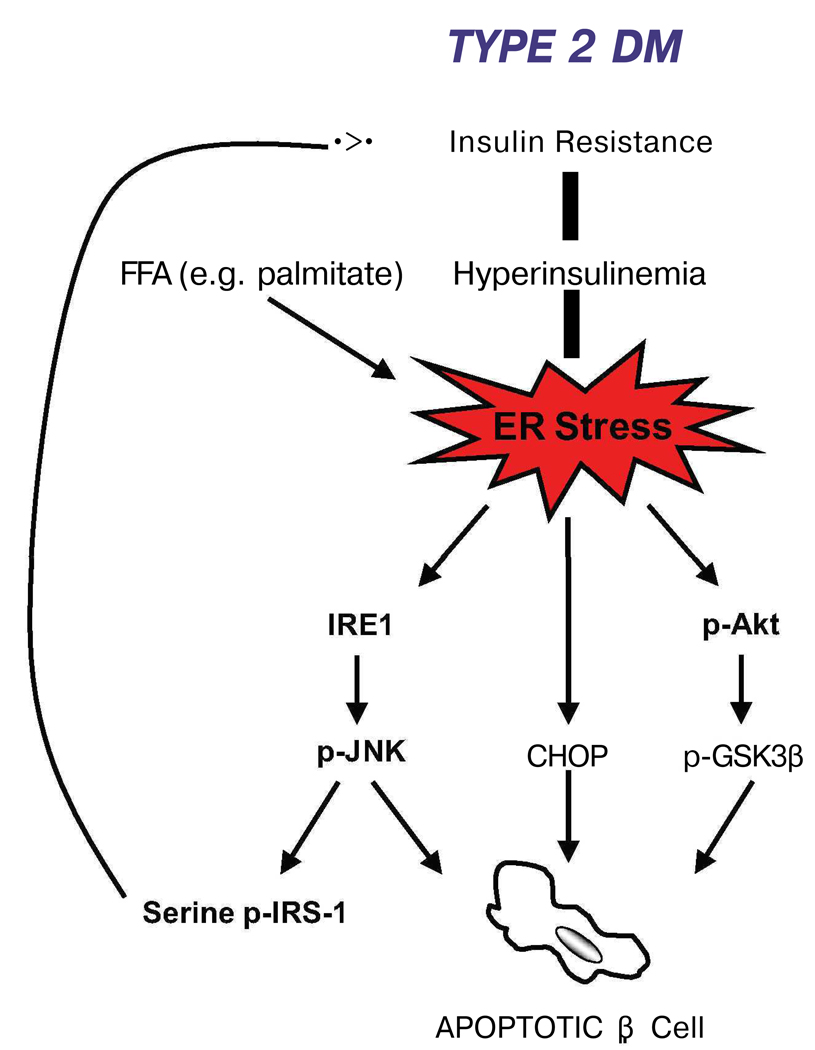

One of the main contributing factors to the pathogenesis type 2 diabetes is the reduction of β-cell mass [38]. Resistance to insulin action in peripheral tissues (i.e. adipose, muscle, and liver) is one of the primary presenting features of this disorder. This insulin resistance leads to the hyper-production of insulin (i.e. hyperinsulinemia) in the β-cell. Hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes develops only in patients that are unable to sustain this compensatory response of the β-cell [39]. This increase in insulin biosynthesis overwhelms the folding capacity of the ER, leading to chronic activation of the UPR. This chronic, hyperactivation of ER stress signaling can lead to β-cell dysfunction and death. There are several components of ER stress signaling that could contribute to this β-cell loss: IRE1-JNK signaling, CHOP, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) (Figure 4). The IRE1 pathway is important in insulin biosynthesis, where transient increases in insulin production lead to IRE1 activation [21]. Chronic activation of IRE1 during prolonged increases in insulin biosynthesis, however, may lead to β-cell death through IRE1-mediated activation of JNK [9]. CHOP is also an important player of ER stress-mediated β-cell death and may promote the progression of type 2 diabetes [31]. A third signaling component, GSK3β, also plays a role in β-cell death caused by ER stress. GSK3β is a substrate of the survival kinase, Akt [40], and it has been demonstrated that attenuation of Akt phosphorylation during ER stress mediates dephosphorylation of GSK3β, leading to ER stress-mediated apoptosis [41].

Figure 4. Type 2 diabetes and ER stress.

There is a feedback loop between insulin resistance, ER stress, and beta cell dysfunction/death. Insulin resistance leads to β-cell exhaustion due to high demand for insulin biosynthesis. This protein overload causes ER stress and activation of pro-apoptotic UPR components. One of these, JNK phosphorylation, indirectly leads to further insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance, a feature of type 2 diabetes, leads to β-cell exhaustion, glucotoxicity, and hyperinsulinemia which place a massive strain on the ER of the β-cell [42]. This, however, is not the only source of stress for the ER. It has recently been shown that free fatty acids (FFAs), specifically long-chain FFAs, also induce β-cell apoptosis [43**,44] (Figure 4). Treatment of β-cell lines with the long-chain FFA, palmitate, increases levels of ER stress markers such as ATF4 and spliced XBP-1. In addition, it has been shown that circulating FFAs lead to β-cell lipotoxicity and consequently excessive ER stress [45].

Recent studies suggest an involvement of ER stress in insulin resistance of liver, muscle, and adipose tissues. IRE1-JNK signaling plays an important role in the insulin-resistant liver tissue of type 2 diabetes patients. Obesity leads to hyper-activation of JNK signaling due to severe ER stress, leading to serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which inhibits insulin action [46]. Like β-cells, hepatocytes have a high baseline ER stress level, and therefore may be sensitive to additional ER stress. It has been shown that high ER stress in liver cells can be resolved via overexpression of the ER-resident chaperone oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150), while suppression of this chaperone in mice inhibits insulin sensitivity [47].

WFS1: The Link between Type 2 Diabetes and ER Stress

Wolfram syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by diabetes mellitus and optical atrophy, was first described by Wolfram and Wagener in 1938 [48]. This syndrome is also described as DIDMOAD (Diabetes Insipidus, Diabetes Mellitus, Optical Atrophy, and Deafness), as patients also present with secondary symptoms in addition to diabetes and optic atrophy. Postmortem studies reveal a non-autoimmune-linked selective loss of pancreatic β-cells [49]. The nuclear gene responsible for this syndrome was identified by two separate groups in 1998 and named WFS1 [50,51].

WFS1 has been shown to be mutated in 90% of patients with Wolfram syndrome [52]. More than 100 mutations of the WFS1 gene have been identified, most of which are inactivating mutations and located in exon 8 which encodes the protein’s transmembrane and C-terminal domains [53,54]. The WFS1 protein has been shown to be localized to the ER, and while ubiquitously expressed, it is highly expressed in the pancreas [55,56]. In the pancreas, it is localized to the β-cell [57**].

WFS1 has also been shown to be a downstream target of IRE1 and PERK signaling, induced transcriptionally and translationally in response to ER stress, and when suppressed, causes high levels of ER stress in the β-cell [57**], suggesting that the pathogenesis of Wolfram syndrome can be attributed to chronic, unresolved ER stress due to the lack of functional WFS1 protein in the β-cell.

Although other endocrine and exocrine cells of the pancreas are active in protein secretion, WFS1 expression levels in these cells are not detectable, as compared with β-cells which are specialized in insulin biosynthesis and secretion. WFS1 expression has been shown to be induced during insulin secretion [21,57**], suggesting that WFS1 is an important component of proinsulin folding and processing in the ER of the β-cell.

The high levels of ER stress and pancreatic β-cell death in patients with Wolfram syndrome may be related to the β-cell dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. The pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes is a result of the peripheral resistance to the action of insulin, which leads to the prolonged increase in insulin biosynthesis. Because the folding capacity of the ER is then overwhelmed, this peripheral resistance to insulin activates ER stress signaling pathways [42]. For this reason, chronic ER stress in β-cells may lead to β-cell apoptosis in patients with type 2 diabetes who are genetically susceptible to ER stress. Indeed, recent genome studies show a link between WFS1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and an increased risk for type 2 diabetes [58**,59].

Future Direction

Our understanding of ER stress signaling in β-cells is far from complete. This is because interactions of the three UPR pathways regulated by the master regulators, IRE1, PERK, and ATF6, have not been studied extensively. System biology approaches using genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics are necessary to the complete understanding of ER stress signaling. However, based on the information that we have today, predictions can be made about the future of research on ER stress signaling in β-cell biology and the consequences for the pathogenesis of diabetes.

Interactions between ER stress signaling and other signaling pathways

Increasing evidence suggests that crosstalk exists between ER stress signaling and other signaling pathways, such as mTOR signaling, JNK signaling, and insulin receptor signaling pathways. The complete understanding of this crosstalk will lead to the discovery of unexpected links between ER stress and biological outcomes, such as cell proliferation and regulation of glucose metabolism.

Discovery of endogenous molecules and chemical compounds that can modulate ER stress and thereby combat ER stress-mediated beta cell death

It has been shown that mild activation of ER stress signaling or specific activation of pro-apoptotic components of ER stress signaling has a beneficial effect on β-cell function and survival [60][21]. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a gut-derived peptide secreted from intestinal L-cells after a meal and has numerous physiological actions, including enhancement of β-cell growth and survival [61]. Interestingly, GLP-1 is a physiological activator of ER stress signaling. Activation of GLP-1 signaling improves β-cell function and survival through the activation of the PERK-ATF4 pathway [62]. We predict that other endogenous factors, like GLP-1 or chemical compounds that can activate ER stress signaling will be discovered and used to increase the viability of β-cells.

Using SNPs of ER stress response genes for prevention of diabetes

Genome-wide association studies have identified numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with increased risk for type-2 diabetes. WFS1 is one of such genes. In the future, human genetics will identify more ER stress-related genes as markers of susceptibility to type 1 and type 2 diabetes. These markers will be potentially useful in targeting patients who would benefit from screening for early detection of diabetes.

Concluding Remarks

To understand the transition from the latent to the overt diabetes state, we need to define the dynamics of β-cell function at the system level. Recent evidence strongly suggests that unresolvable severe ER stress leads to β-cell dysfunction and death during the progression of type1 and type 2 diabetes, as well as genetic forms of diabetes such as Wolfram syndrome. A complete understanding of the states of protein homeostasis regulated by ER stress signaling pathways will have a direct impact on future therapies for diabetes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIH-NIDDK (R01DK067493), the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (5 P30 DK32520), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, and the Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period or review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** or outstanding interest

- 1.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. That which does not kill me makes me stronger: adapting to chronic ER stress. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urano F, Bertolotti A, Ron D. IRE1 and efferent signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3697–3702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen X, Ellis RE, Lee K, Liu CY, Yang K, Solomon A, Yoshida H, Morimoto R, Kurnit DM, Mori K, et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell. 2001;107:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Hosokawa N, Kaufman RJ, Nagata K, Mori K. A timedependent phase shift in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Dev Cell. 2003;4:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishitoh H, Saitoh M, Mochida Y, Takeda K, Nakano H, Rothe M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for JNK/SAPK activation by TRAF2. Molecular Cell. 1998;2:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida H, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Identification of the cis-acting endoplasmic reticulum stress response element responsible for transcriptional induction of mammalian glucose-regulated proteins. Involvement of basic leucine zipper transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33741–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye J, Rawson RB, Komuro R, Chen X, Dave UP, Prywes R, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. ER stress induces cleavage of membrane-bound ATF6 by the same proteases that process SREBPs. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1355–1364. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida H, Okada T, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Negishi M, Mori K. ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6755–6767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6755-6767.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *19.Yamamoto K, Sato T, Matsui T, Sato M, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A, Mori K. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6alpha and XBP1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018.This study is the first characterization of ATF6α and ATF6β knockout mice. Analysis of these animals reveal that the α isoform of ATF6 is solely responsible for the transcriptional induction of ER chaperones during ER stress. Also of importance is the illustration that ATF6α and another ER transcription factor, XBP1, heterodimerize to induce ER-associated degradation (ERAD) components. The authors demonstrate that in mamals, ATF6 is the major regulator of ER quality proteins, which is on contrast to Drosophila and C. elegans.

- 20.Hong M, Li M, Mao C, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers an acute proteasome-dependent degradation of ATF6. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:723–732. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **21.Lipson KL, Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, Nguyen LX, Foss E, Bortell R, Rossini AA, Urano F. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab. 2006;4:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007.This is the first study which shows a link between ER stress signaling and insulin biosynthesis. Phosphorylation of the ER-resident kinase, IRE1α, which occurs as a result of acute exposure of the β-cell to high glucose treatment, is coupled to insulin production. When IRE1α is inactivated, insulin biosynthesis is reduced. This study is also novel in that it is demonstrated that acute, high glucose-mediated IRE1α phosphorylation is not accompanied by BiP dissociation, nor does it lead to XBP-1 splicing. Thus, this work reveals a beneficial effect of ER stress signaling activation in pancreatic β-cells.

- 22.Wolcott CD, Rallison ML. Infancy-onset diabetes mellitus and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1972;80:292–297. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delepine M, Nicolino M, Barrett T, Golamaully M, Lathrop GM, Julier C. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:406–409. doi: 10.1038/78085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding HP, Zeng H, Zhang Y, Jungries R, Chung P, Plesken H, Sabatini DD, Ron D. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Molecular Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheuner D, Mierde DV, Song B, Flamez D, Creemers JW, Tsukamoto K, Ribick M, Schuit FC, Kaufman RJ. Control of mRNA translation preserves endoplasmic reticulum function in beta cells and maintains glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2005;11:757–764. doi: 10.1038/nm1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan W, Frank CL, Korth MJ, Sopher BL, Novoa I, Ron D, Katze MG. Control of PERK eIF2alpha kinase activity by the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced molecular chaperone P58IPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15920–15925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252341799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladiges WC, Knoblaugh SE, Morton JF, Korth MJ, Sopher BL, Baskin CR, MacAuley A, Goodman AG, LeBoeuf RC, Katze MG. Pancreatic beta-cell failure and diabetes in mice with a deletion mutation of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone gene P58IPK. Diabetes. 2005;54:1074–1081. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Stoy J, Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Ye H, Paz VP, Pluzhnikov A, Below JE, Hayes MG, Cox NJ, Lipkind GM, et al. Insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15040–15044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707291104.This is an important study which shows that insulin gene mutations can also lead to permanent neonatal diabetes. Using a combination of gene linkage and candidate gene approaches in patients with neonatal diabetes, the authors identified insulin gene mutations. The mutations identified were in a critical region of preproinsulin, and the authors predicted these would cause insulin to misfold, leading to ER stress-mediated apoptosis. Indeed, one the mutations identified was identical to that found in the Akita mouse, a model of ER stress-mediated diabetes.

- 29.Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, Kubo SK, Kayo T, Lu D, Takata K, Koizumi A, Izumi T. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herbach N, Rathkolb B, Kemter E, Pichl L, Klaften M, de Angelis MH, Halban PA, Wolf E, Aigner B, Wanke R. Dominant-negative effects of a novel mutated Ins2 allele causes early-onset diabetes and severe beta-cell loss in Munich Ins2C95S mutant mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:1268–1276. doi: 10.2337/db06-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:525–532. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casciola-Rosen LA, Anhalt GJ, Rosen A. DNA-dependent protein kinase is one of a subset of autoantigens specifically cleaved early during apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1625–1634. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eizirik DL, Flodstrom M, Karlsen AE, Welsh N. The harmony of the spheres: inducible nitric oxide synthase and related genes in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 1996;39:875–890. doi: 10.1007/BF00403906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M, Gotoh T, Matsumoto M, Wada I, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardozo AK, Heimberg H, Heremans Y, Leeman R, Kutlu B, Kruhoffer M, Orntoft T, Eizirik DL. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine-induced and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48879–48886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **36.Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J, Feng YM, Rasschaert J, Tonnesen M, Van Eylen F, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Herchuelz A, Eizirik DL. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:452–461. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.452.Here, the authors show decisively the mechanism behind cytokine-induced ER stress in the β-cell. The cytokines which have been shown to be mediators of β-cell death in type 1 diabetes, IL-1β and IFN-γ, deplete the ER of calcium via NO production which blocks the calcium pump, SERCA2b, ultimately leading to high levels of ER stress. This severe stress leads to the upregulation of proapoptotic CHOP expression. In β-cell lines, the authors show that this leads to an increase in cell apoptosis.

- 37.Hartman MG, Lu D, Kim ML, Kociba GJ, Shukri T, Buteau J, Wang X, Frankel WL, Guttridge D, Prentki M, et al. Role for activating transcription factor 3 in stress-induced beta-cell apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5721-5732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leahy JL. Detrimental effects of chronic hyperglycemia on the pancreatic beta-cells. In: LeRoith D, Taylor SI, Olefsky JM, editors. Diabetes Mellitus. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan S, Ohsugi M, Liu Z, Fatrai S, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Permutt MA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis is partly mediated by reduced insulin signaling through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in mouse insulinoma cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:968–975. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alarcon C, Wicksteed B, Prentki M, Corkey BE, Rhodes CJ. Succinate is a preferential metabolic stimulus-coupling signal for glucose-induced proinsulin biosynthesis translation. Diabetes. 2002;51:2496–2504. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **43.Karaskov E, Scott C, Zhang L, Teodoro T, Ravazzola M, Volchuk A. Chronic palmitate but not oleate exposure induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may contribute to INS-1 pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3398–3407. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1494.This paper explores the mechanisms of FFA-induced β-cell apoptosis. This study is novel in that it reveals that long-chain FFAs, such as palmitate, cause ER stress. Interestingly, while palmitate induced the expression of the proapoptotic UPR component, CHOP, it did not induce expression of protective components, such as the chaperones BiP and PDI.

- 44.Cnop M, Ladriere L, Hekerman P, Ortis F, Cardozo AK, Dogusan Z, Flamez D, Boyce M, Yuan J, Eizirik DL. Selective inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha dephosphorylation potentiates fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3989–3997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kharroubi I, Ladriere L, Cardozo AK, Dogusan Z, Cnop M, Eizirik DL. Free fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-kappaB and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5087–5096. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Gorgun C, Glimcher LH, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawamori D, Kaneto H, Nakatani Y, Matsuoka TA, Matsuhisa M, Hori M, Yamasaki Y. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 bridges the JNK pathway and the transcription factor PDX-1 through its intracellular translocation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1091–1098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolfram DJ, Wagener HP. Diabetes mellitus and simple optic atrophy among siblings: report of four cases. May Clin Proc. 1938;1:715–718. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karasik A, O'Hara C, Srikanta S, Swift M, Soeldner JS, Kahn CR, Herskowitz RD. Genetically programmed selective islet beta-cell loss in diabetic subjects with Wolfram's syndrome. Diabetes Care. 1989;12:135–138. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Wasson J, Behn P, Kalidas K, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Mueckler M, Marshall H, Donis-Keller H, Crock P, et al. A gene encoding a transmembrane protein is mutated in patients with diabetes mellitus and optic atrophy (Wolfram syndrome) Nature Genetics. 1998;20:143–148. doi: 10.1038/2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strom TM, Hortnagel K, Hofmann S, Gekeler F, Scharfe C, Rabl W, Gerbitz KD, Meitinger T. Diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness (DIDMOAD) caused by mutations in a novel gene (wolframin) coding for a predicted transmembrane protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:2021–2028. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.13.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khanim F, Kirk J, Latif F, Barrett TG. WFS1/wolframin mutations, Wolfram syndrome, and associated diseases. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:357–367. doi: 10.1002/humu.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardy C, Khanim F, Torres R, Scott-Brown M, Seller A, Poulton J, Collier D, Kirk J, Polymeropoulos M, Latif F, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic analysis of 19 Wolfram syndrome kindreds demonstrating a wide spectrum of mutations in WFS1. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1279–1290. doi: 10.1086/302609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cryns K, Sivakumaran TA, Van den Ouweland JM, Pennings RJ, Cremers CW, Flothmann K, Young TL, Smith RJ, Lesperance MM, Van Camp G. Mutational spectrum of the WFS1 gene in Wolfram syndrome, nonsyndromic hearing impairment, diabetes mellitus, and psychiatric disease. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:275–287. doi: 10.1002/humu.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeda K, Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Matsuzaki Y, Oba J, Watanabe Y, Shinoda K, Oka Y. WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome 1) gene product: predominant subcellular localization to endoplasmic reticulum in cultured cells and neuronal expression in rat brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:477–484. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hofmann S, Philbrook C, Gerbitz KD, Bauer MF. Wolfram syndrome: structural and functional analyses of mutant and wild-type wolframin, the WFS1 gene product. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2003–2012. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **57.Fonseca SG, Fukuma M, Lipson KL, Nguyen LX, Allen JR, Oka Y, Urano F. WFS1 Is a Novel Component of the Unfolded Protein Response and Maintains Homeostasis of the Endoplasmic Reticulum in Pancreatic {beta}-Cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39609–39615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507426200.This study reveals a novel, β-cell-specific component of ER stress signaling, WFS1. Here, it is shown that WFS1 is a downstream target of PERK and IRE1α signaling and is upregulated during ER stress. WFS1 is localized to the β-cell of the pancreas, and when it is suppressed, leads to apoptosis. This study links a genetic form of diabetes, Wolfram syndrome, to ER stress.

- **58.Sandhu MS, Weedon MN, Fawcett KA, Wasson J, Debenham SL, Daly A, Lango H, Frayling TM, Neumann RJ, Sherva R, et al. Common variants in WFS1 confer risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:951–953. doi: 10.1038/ng2067.This study is significant in that it links a genetic form of type 1 diabetes, Wolfram syndrome, to type 2 diabetes and ER stress. Here, the authors assessed the association of candidate SNPs in Ashkenazi and UK populations with diabetes risk. Two SNPs were identified in all four of their studies, which was located in the WFS1 gene.

- 59.Franks PW, Rolandsson O, Debenham SL, Fawcett KA, Payne F, Dina C, Froguel P, Mohlke KL, Willer C, Olsson T, et al. Replication of the association between variants in WFS1 and risk of type 2 diabetes in European populations. Diabetologia. 2008;51:458–463. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0887-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han D, Upton JP, Hagen A, Callahan J, Oakes SA, Papa FR. A kinase inhibitor activates the IRE1alpha RNase to confer cytoprotection against ER stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yusta B, Baggio LL, Estall JL, Koehler JA, Holland DP, Li H, Pipeleers D, Ling Z, Drucker DJ. GLP-1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2006;4:391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]