An Epigenetic Role for Maternally Inherited piRNAs in Transposon Silencing (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Jan 12.

Published in final edited form as: Science. 2008 Nov 28;322(5906):1387–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1165171

Abstract

In plants and mammals, small RNAs indirectly mediate epigenetic inheritance by specifying cytosine methylation. We found that small RNAs themselves serve as vectors for epigenetic information. Crosses between Drosophila strains that differ in the presence of a particular transposon can produce sterile progeny, a phenomenon called hybrid dysgenesis. This phenotype manifests itself only if the transposon is paternally inherited, suggesting maternal transmission of a factor that maintains fertility. In both _P_- and _I_-element–mediated hybrid dysgenesis models, daughters show a markedly different content of Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) targeting each element, depending on their parents of origin. Such differences persist from fertilization through adulthood. This indicates that maternally deposited piRNAs are important for mounting an effective silencing response and that a lack of maternal piRNA inheritance underlies hybrid dysgenesis.

In Drosophila melanogaster, the progeny of intercrosses between wild-caught males and laboratory-strain females are sterile because of defects in gametogenesis, whereas the genetically identical progeny of wild-caught females and laboratory-strain males remain fertile (1–3). This phenomenon, known as hybrid dysgenesis, was attributed to the mobilization in dysgenic progeny of _P_-element or _I_-element transposons, which were present in wild-caught flies but absent from laboratory strains (4–9). The disparity in outcomes, depending on the parent of transposon origin, indicated the existence of cytoplasmically inherited determinants of the phenotype, which must be transmitted through the maternal germ line (8, 9).

The control of mobile elements in germ cells depends heavily on a small RNA-based immune system, composed of Piwi-family proteins (Piwi, Aubergine, and AGO3) and piRNAs (10, 11). Both Piwi and Aubergine (Aub) are deposited into developing oocytes and accumulate in the pole plasm (12, 13), implying possible transfer of maternal piRNAs into the germ lines of their progeny. We therefore asked whether maternally deposited small RNAs might affect transposon suppression in a heritable fashion and whether piRNAs might be the maternal suppressor of hybrid dysgenesis.

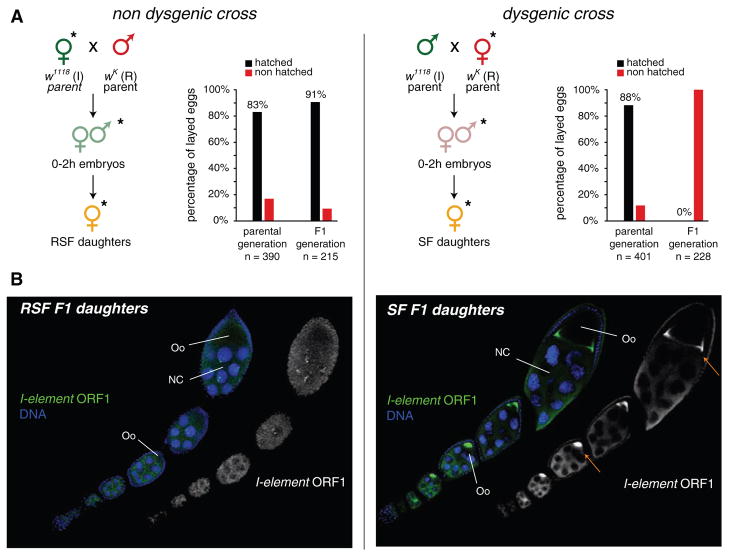

We first focused on _I_-element–induced hybrid dysgenesis (14). A cross of inducer males carrying active _I_-elements (designated “I” in Fig. 1) to reactive females devoid of active _I_-elements (designated “R”) yielded dysgenic daughters (termed SF; Fig. 1 and fig. S1) (5, 6, 8, 15). These were sterile, despite normal ovarian morphology. Sterility correlated with _I_-element expression in SF ovaries (Fig. 1B) (16). The reciprocal cross of inducer females to reactive males yielded fertile progeny (termed RSF; Fig. 1 and fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

The I-R hybrid dysgenesis system. (A) Crossing scheme to generate nondysgenic (left) and dysgenic (right) progeny. Small RNA libraries were made from flies indicated by asterisks. Bar diagrams indicate fertility analysis of parental and F1 females on the basis of egg hatching rates. n, number of counted eggs. (B) Immunofluorescence for _I_-element ORF1 (green) is shown for nondysgenic (RSF) and dysgenic (SF) daughters. Oo, oocyte; NC, nurse cells.

We sequenced 18- to 29-nucleotide RNAs from the ovaries of inducer (w1118) and reactive (wk) strains, 0- to 2-hour embryos from dysgenic and nondysgenic crosses, and ovaries from SF and RSF daughters (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). Both parental ovary and early embryo libraries contained similarly complex small RNA populations (fig. S1A). This indicates that small RNAs were maternally deposited, because the zygotic genome remains inactive during most of the period that we analyzed.

In Drosophila, piRNAs loaded into the Piwi, Aub, and AGO3 proteins exhibit distinctive features (17, 18). piRNAs occupying Piwi and Aub are predominantly antisense to transposons and contain a 5′ terminal uridine residue (1U; fig. S2A). In contrast, AGO3 harbors mainly sense piRNAs with a strong bias for adenosine at position 10 (10A; fig. S2B). On the basis of these characteristics, we could infer the binding partner(s) for many small RNAs within our sequenced populations. A comparison of small RNAs in mothers and embryos indicated robust maternal inheritance for the Aub/Piwi pool and substantial but weaker deposition of AGO3-bound piRNAs (fig S2, A and B). This observation is consistent with the degree of maternal deposition of the corresponding Piwi-family proteins (figs. S3 and S4) (12, 13).

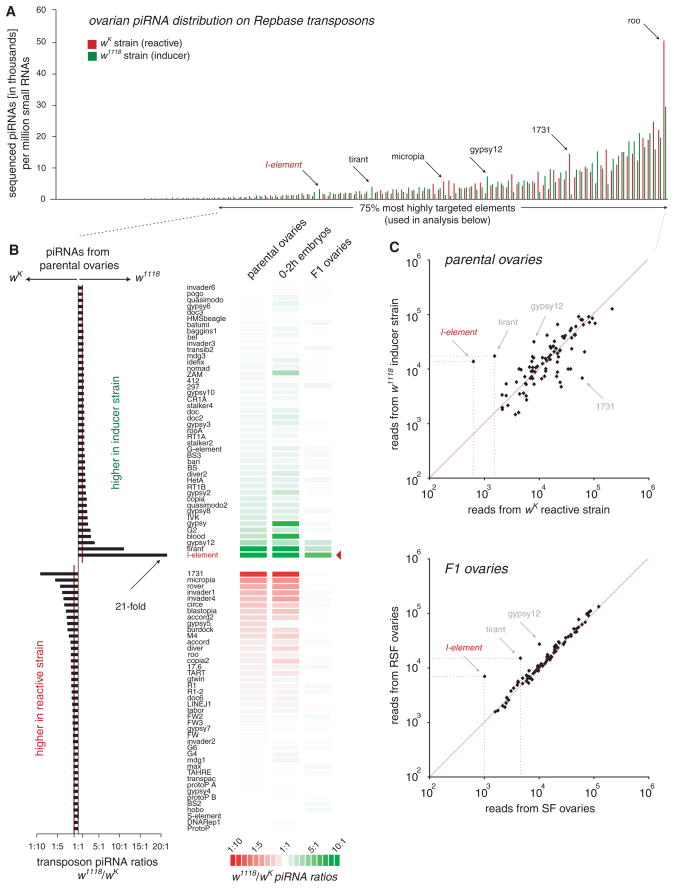

Patterns of ovarian piRNAs targeting individual D. melanogaster transposons showed marked similarity between inducer and reactive strains (Fig. 2A). However, there were notable differences (Fig. 2, B and C). The _I_-element exhibited the lowest piRNA count in the reactive strain and the greatest disparity (21-fold) between strains (Fig. 2, B and C, and fig. S5A). Less pronounced differences were noted for tirant and gypsy12, which were more heavily targeted in the inducer strain, and for 1731 and micropia, which were more heavily targeted in the reactive strain (Fig. 2, B and C). These differences were mirrored in corresponding embryonic libraries, with reactive mothers depositing 12-fold fewer _I_-element piRNAs than inducer mothers (Fig. 2B). This supports the hypothesis that piRNAs correspond to the maternally transmitted phenotypic determinant noted in many studies of hybrid dysgenesis.

Fig. 2.

I-R hybrid dysgenesis correlates with maternal piRNA inheritance. (A) Normalized piRNA counts for Repbase transposons are plotted for w1118 inducer and wK reactive ovaries. (B) (Left) Fold differences in piRNA counts comparing w1118 and wK mothers are shown (red line indicates a 1:1 ratio). (Right) Transposon piRNA ratios for mothers, embryos, and F1 progeny (SF: RSF ratio) are shown as a heat map. (C) Scatter plots indicating transposon piRNA correlations between w1118 and wK mothers (top) and their respective intercross progeny (bottom).

The outcome of an inducer-reactive (I-R) dysgenic cross manifests itself not in embryos but in adults. We therefore asked whether differences in maternally deposited piRNAs continued to influence adult piRNA profiles 2 weeks after fertilization. Consistent with their being genetically identical, SF and RSF daughters had virtually identical piRNA levels targeting nearly all transposons (Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, piRNA profiles for many elements had adjusted to a stable equilibrium during the course of germline development. As an example, for 1731 a ninefold difference in piRNA levels between mothers had equalized in progeny (fig. S5B). In RSF females, _I_-element piRNAs dropped twofold as compared with their inducer mothers (fig. S5B). This paralleled the overall reduction in active _I_-element load as the inducer genome was diluted by that of the reactive strain. However, limits on the adaptability of the system are seen in SF daughters for the _I_-element and, to a lesser degree, for tirant and gypsy12 (Fig. 2, B and C, and fig. S5). Though SF daughters contained ~1.6-fold more _I_-element piRNAs than their reactive mothers, these were still sevenfold less abundant than in RSF daughters. This deficit ultimately results in de-repression of the paternally inherited, active _I_-elements and in sterility (Fig. 1, A and B).

Though active _I_-elements are confined to inducer strains, all D. melanogaster strains contain ancestral _I_-related fragments, (6, 19–21). These are typically found in heterochromatin and exhibit 80 to 95% identity to the modern _I_-element. Such fragments have been proposed to mediate adaptation to and suppression of _I_-elements in inducer strains (15, 22–24). To understand the lack of adaptation to _I_-elements in SF daughters, we probed the nature of interaction between active and ancestral _I_-element sequences.

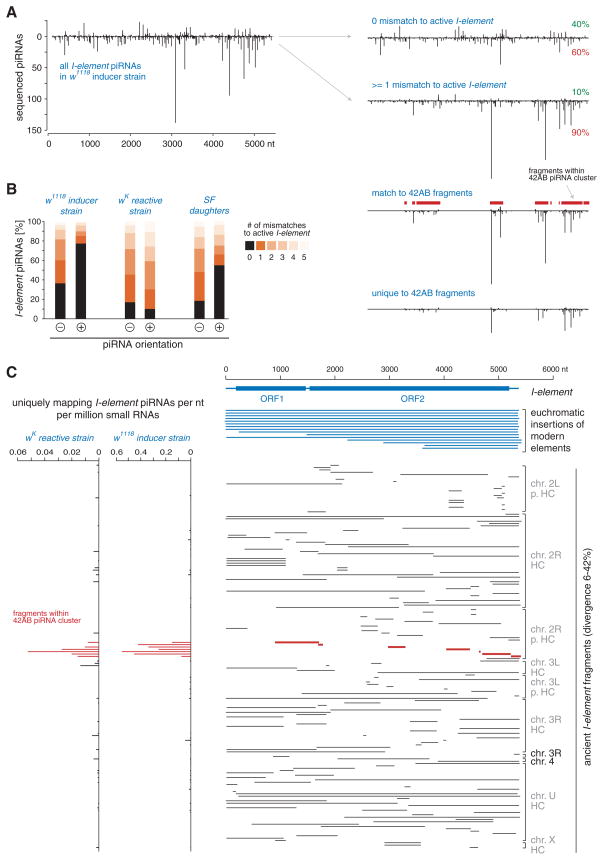

The ping-pong model of piRNA biogenesis and silencing describes a Slicer-dependent amplification cycle between active transposons and transposon fragments resident in piRNA clusters (17, 18). Sequence features fitting this model were obvious in piRNAs from the inducer strain (fig. S6). More than half of all _I_-element piRNAs deviated from the modern sequence and, therefore, must have originated from ancestral fragments (Fig. 3A). Of those piRNAs, the overwhelming majority (90%) were antisense. As a whole, sense-oriented species showed a strong tendency (~78%) to originate from modern active _I_-element copies (Fig. 3B), whereas 63% of antisense species must have originated from heterochromatic fragments.

Fig. 3.

A piRNA amplification loop between active _I_-elements and ancestral fragments. (A) Density profile of piRNAs matching the _I_-element with up to five mismatches (left) and profiles for those species with zero (top right) or at least one mismatch (below) to the active element (sense/antisense fractions in red and green) are shown. Profiles below indicate species that have the potential (upper) or must (lower) derive from the 42AB piRNA cluster. _I_-element fragments contained within the 42AB cluster are indicated in red. (B) Shown are fractions of _I_-element piRNAs from w1118, wK mothers, and SF daughters (right) that match the active sequence with the indicated number of mismatches, split into sense (+) and antisense (−). (C) (Right) All _I_-element fragments in the Release 5 genome sequence [split into modern insertions (blue) and ancestral fragments (black) and sorted by chromosomal position] are shown (gray coloring indicates heterochromatic; HC, heterochromatin; p. HC, pericentromeric HC). Red fragments map to the 42AB piRNA cluster. (Left) Bar diagrams indicate the density of piRNAs mapping uniquely to the ancestral fragments shown at right (42AB fragments in red). As fragments with high piRNA density were not more divergent overall, clustering in 42AB is not an artifact of analysis (fig. S7).

Because the reactive strain lacks active _I_-element copies, no ping-pong amplification occurred, and piRNAs mapping to the sense or antisense strand showed no distinguishing pattern of matching to the active element (Fig. 3B). Despite the lack of an efficient silencing response in SF daughters, we still observed a clear trend for sense piRNAs to originate from active _I_-element copies, which were paternally transmitted (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with the adaptive system having begun to mount a response in SF daughters, although they ultimately failed to silence the element.

In both reactive and inducer strains, the 42AB cluster represents a major source of piRNAs targeting a variety of mobile elements (fig. S8) (17). Of all heterochromatic _I_-fragments present in the sequenced melanogaster strain, seven lie within 42AB, and we verified the existence of all in both our reactive and inducer strains (fig. S9). None of the other heterochromatic _I_-fragments lie within the remaining 19 most active clusters. In the inducer strain, the majority of heterochromatin-derived _I_-element piRNAs arose from ancestral fragments within 42AB, including many of the most abundant species (Fig. 3, A and C). Despite a more than 20-fold difference in their relative levels, _I_-element piRNAs matching heterochromatic fragments were also derived from 42AB in the reactive strain (Fig. 3C).

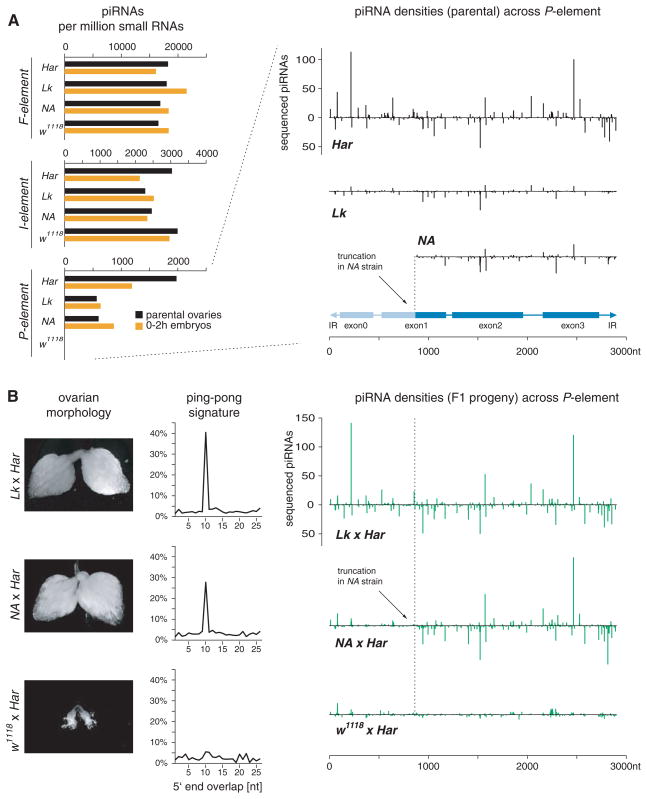

We sought to test whether the role of maternally inherited small RNAs in transposon silencing was general. In P-strain/M-strain (P-M) hybrid dysgenesis, crosses between males containing _P_-elements (P-strains) and females devoid of such elements (M-strains) yield sterile progeny with severe gonadal atrophy (GD sterility) (3, 9). We examined small RNAs from Harwich (Har), a P-strain containing 30 to 50 _P_-element copies, and w1118, here serving as an M-strain. Harwich showed strong maternal deposition of _P_-element piRNAs, whereas both M-strain mothers and their 0- to 2-hour embryos lacked such species (Fig. 4A). This contrasted with _I_- and _F_-element piRNAs, which were abundant in parents and embryos from both strains. Crosses between Harwich males and w1118 females yielded dysgenic (GD) progeny. Because of the impact of severe gonadal atrophy (Fig. 4B and table S1), we normalized the daughter library using piRNAs targeting the _F_-element, a transposon exhibiting consistent profiles in all strains examined. Clearly, dysgenic daughters lacked prominent _P_-element piRNAs and signatures of the ping-pong amplification cycle (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Suppression of P-M hybrid dysgenesis correlates with maternally deposited piRNAs. (A) Normalized number of ovarian (black) and early embryonic (orange) piRNAs from the indicated strains mapping to the _F_-, _I_-, and _P_-elements with up to three (F and I) or with one (P) mismatch(es). To the right (sense, upper; antisense, lower), densities of piRNAs are displayed over the _P_-element in parental ovaries of the Har, LK, and NA strains. The extent of the truncation of the telomeric _P_-insertion in the NA strain is indicated. The intron-exon structure of the _P_-element is shown below. (B) F1 ovarian morphology, ping-pong signature, and piRNA densities from nondysgenic (LK × Har and NA × Har) and dysgenic (w1118 × Har) F1 progeny are shown.

_Lerik_-P(1A) (designated Lk) contains two _P_-elements in the X-TAS piRNA cluster, and _Nasr’Allah_-P(1A) (designated NA) contains a single 5′ truncated insertion at the same locus (25, 26). Lk and NA both produce and maternally deposit _P_-element piRNAs (Fig. 4A), with these species in the NA strain precisely corresponding to the extent of its only _P_-fragment (Fig. 4A) (25). Unlike w1118, Lk and NA mothers were able to produce fertile offspring with Harwich. This result correlated with robust piRNA production in daughter ovaries and with a strong signature of the ping-pong amplification cycle.

The 5′ end of the _P_-element largely lacked piRNAs, particularly antisense species, in both dysgenic flies and fertile _NA_-Harwich progeny (Fig. 4B). NA does not deposit maternal piRNAs corresponding to this region, because of the truncation of its _P_-element in X-TAS. Thus, maternal piRNAs are important for potent piRNA generation in daughters, even when the _P_-element is being effectively silenced by piRNAs matching other parts of the transposon.

piRNA clusters have been envisioned as a genetic reservoir of transposon resistance, with immunity being determined by the content of these loci (17). Our data indicate that the content of piRNA clusters alone is insufficient to provide resistance to at least some elements within a single generation. Instead, maternally inherited small RNAs appear to be essential to prime the resistance system at each generation to achieve full immunity (see also 27).

In the I-R system, environmental factors influence the severity of the phenotype in a dysgenic cross (28) in a manner linked to the expression level of ancestral _I_-fragments (29). Rearing of reactive mothers at elevated temperature or increases in maternal age raise the proportion of fertile progeny. These observations suggest that the experience of the mother translates into a dominant effect on progeny. Our data suggest that this experience may be transmitted through variations in maternally deposited small RNA populations. Thus, transmission of instructive piRNA populations, shaped by both genetic and environmental factors, may provide a previously unknown mechanism for epigenetic inheritance.

Supplementary Material

Science-s1

References and Notes

- 1.Picard G, L’Heritier P. Drosophila Inf Serv. 1971;46:54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picard G. Genetics. 1976;83:107. doi: 10.1093/genetics/83.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidwell MG, Kidwell JF, Sved JA. Genetics. 1977;86:813. doi: 10.1093/genetics/86.4.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin GM, Kidwell MG, Bingham PM. Cell. 1982;29:987. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelisson A. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;183:123. doi: 10.1007/BF00270149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bucheton A, Paro R, Sang HM, Pelisson A, Finnegan DJ. Cell. 1984;38:153. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kidwell MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambeyron S, Bucheton A. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:215. doi: 10.1159/000084955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro JP, Carareto CM. Genetica. 2004;121:107. doi: 10.1023/b:gene.0000040382.48039.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J. Science. 2007;318:761. doi: 10.1126/science.1146484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W. Development. 2008;135:3. doi: 10.1242/dev.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Megosh HB, Cox DN, Campbell C, Lin H. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1884. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris AN, Macdonald PM. Development. 2001;128:2823. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 15.Jensen S, Cavarec L, Gassama MP, Heidmann T. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:381. doi: 10.1007/BF02191637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seleme MC, Busseau I, Malinsky S, Bucheton A, Teninges D. Genetics. 1999;151:761. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennecke J, et al. Cell. 2007;128:1089. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunawardane LS, et al. Science. 2007;315:1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1140494. published online 21 February 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimitri P, Bucheton A. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:160. doi: 10.1159/000084948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crozatier M, Vaury C, Busseau I, Pelisson A, Bucheton A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9199. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.19.9199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaury C, Abad P, Pelisson A, Lenoir A, Bucheton A. J Mol Evol. 1990;31:424. doi: 10.1007/BF02106056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen S, Gassama MP, Dramard X, Heidmann T. Genetics. 2002;162:1197. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen S, Gassama MP, Heidmann T. Nat Genet. 1999;21:209. doi: 10.1038/5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malinsky S, Bucheton A, Busseau I. Genetics. 2000;156:1147. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marin L, et al. Genetics. 2000;155:1841. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronsseray S, Lehmann M, Anxolabehere D. Genetics. 1991;129:501. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenstiel JP, Hartl DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucheton A. Heredity. 1978;41:357. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1978.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dramard X, Heidmann T, Jensen S. PLoS One. 2007;2:e304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.We thank M. Rooks and D. McCombie (CSHL) for help with deep sequencing, S. Jensen and S. Ronsseray for fly stocks and helpful discussions, and D. Finnegan for the _I_-element ORF-1 antibody. J.B. is supported by a fellowship from The Ernst Schering Foundation, C.D.M. is a Beckman fellow of the Watson School of Biological Sciences and is supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, and A.S. is supported by a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship. This work was supported by grants from NIH to G.J.H. and A.A.A. and a kind gift from K. W. Davis (to G.J.H.). Small RNA libraries are deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE13081, data sets GSM327620 to GSM327634).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Science-s1