Millennials and the World of Work: Experiences in Paid Work During Adolescence (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Jun 1.

Published in final edited form as: J Bus Psychol. 2010 Jun;25(2):247–255. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9167-4

Abstract

Purpose

This article considers some important questions faced by youth as they enter and adapt to paid work. We focus on two key questions: (1) how many hours should teenagers work during the school year and (2) what available jobs are desirable?

Design/Methodology/Approach

To help answer these questions, we review studies that have examined the effects of early work experiences on academic achievement, positive youth development, and health-risk behaviors. We also draw upon nationally representative data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study to illustrate some new findings on youth employment.

Findings

Moderate work hours, especially in jobs of higher-quality, are associated with a broad range of positive developmental outcomes.

Implications

These questions are not only important to teenagers and their parents, they also reflect key debates among scholars in sociology, developmental psychology, and economics regarding the potential short- and long-term consequences of early work experiences for social development and socioeconomic achievement.

Originality/Value

Although work intensity is an important dimension of adolescent work experience, it is clearly not the only one and we argue that it may not even be the most important one. By focusing on types and qualities of jobs, more can be gained in terms of understanding for whom and under what conditions teenage work does provide benefits for and detriments to youth development.

Keywords: Teenage employment, School-to-work transition, School achievement, Problem behaviors, Work quality, Life course studies

Combining school and work during adolescence, a fairly recent and largely American phenomenon, is common for the vast majority of young people today (Staff et al. 2009). This sharing of work and school roles begins early in adolescence (Entwisle et al. 2000), and research shows that many youth today leave school with an extensive history of employment experiences (Light 2001; Mortimer 2003; Staff and Mortimer 2007). Done well, the combination of work and school in adolescence can have some benefits concerning the development of independence and other skills useful for the transition to adulthood; done poorly, there are numerous detriments involving school failure and health-risk behaviors. Once the decision to work is made, young people face two key questions: (1) how many hours should they work and (2) where should they work? These questions are not only important to teenagers today and their parents, they also reflect key debates among scholars in sociology, developmental psychology, and economics regarding the potential costs and benefits of paid work for adolescent adjustment and achievement.

To help answer these questions, we first provide a brief review of studies that have examined the effects of early work experiences on academic achievement, positive youth development, and health-risk behaviors. We then highlight some new evidence on this issue using data from the ongoing Monitoring the Future (MTF) study. Since 1976, the MTF project has collected data on large (approximately 17,000 students per grade) samples of middle and high schools students in the United States each year (Johnston et al. 2008a, b). Though the MTF project has collected data on the employment experiences of earlier generations of young people (e.g., late Boomers, Generation Xers), most of the findings we highlight in this article are based upon nationally representative samples of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders born between the years 1977 and 2000, or youth comprising the Millennial generation.

How Many Hours Should Youth Work?

As mentioned before, employment often begins in middle school (Entwisle et al. 2000) and increases with age such that almost all youth have some experience in paid work while attending high school (National Research Council 1998; U.S. Department of Labor 2000). For instance, in the MTF study between 1977 and 2000, only 35% of 8th graders and 40% of 10th graders were employed when school is in session, while over 75% of 12th graders worked in paid jobs (Staff et al. 2009). It is clear that youth spend longer hours at work as they progress through secondary school. Eight percent of the employed 8th graders in the MTF worked over 20 hours per week during the school year, compared to 40% of employed 12th graders (Staff et al. 2009).

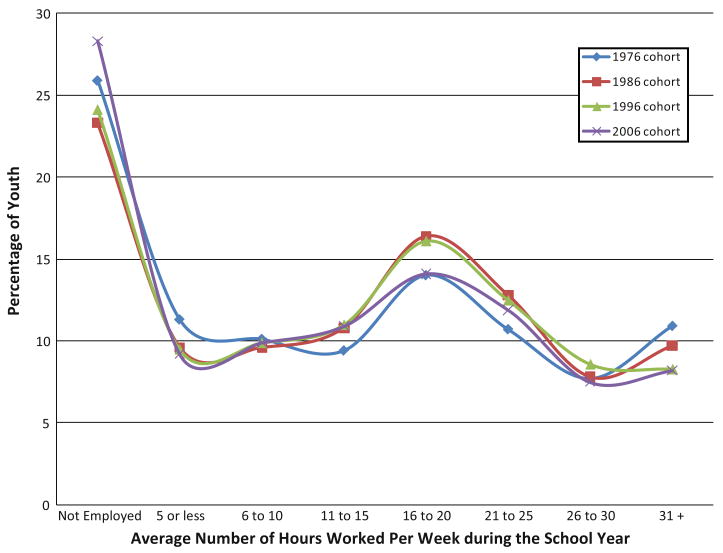

Are the early work experiences of the Millennials different from earlier generations of youth? As we have described in our previous research (Staff et al. 2009), the percentage of employed students and the number of hours they work has changed very little in the past 40 years (see also Ruhm 1997). For example, Fig. 1 shows the distribution of workers and the number of hours worked during the school year for nationally representative samples of 12th graders in 1976, 1986, 1996, and 2006. As shown in Fig. 1, the number of non-working 12th graders in 2006 (approximately 27%) is slightly, but not significantly, higher than in 1976. Nevertheless, the distribution of hours worked among employed youth during the school year is remarkably similar across the four cohorts of youth comprising late Boomers, Generation Xers, and Millennials.

Fig. 1.

Percent of employed students and number of hours worked during the school year: MTF 12th graders (1976, 1986, 1996, and 2006 12th-grade cohorts). Source: Staff, J., Messersmith, E. E., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2009). Adolescents and the world of work. In R. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., pp. 270–313). New York: John Wiley & Sons

If the majority of teenagers today work while attending secondary school, then how much should they work? On the one hand, some scholars have argued that the number of hours worked during the school week has a negative association with school success and with positive youth development (Greenberger and Steinberg 1986). Indeed, research shows that youth across the generations who spend long hours on the job report fewer hours of homework and participation in school-related sports, clubs, and other activities; lower standardized test scores and grade point averages (GPAs); and a lower probability of high school graduation than youth who do not work or who limit their hours (Lee and Staff 2007; Marsh and Kleitman 2005; Osgood 1999). Long hours on the job are also associated with potential health-risk behaviors such as less sleep, exercise, and healthy eating (Bachman and Schulenberg 1993). In addition, youth across the generations who work intensively are more likely to engage in unsupervised activities with their friends, such as going to parties, riding around in cars for fun, and spending evenings out for fun and recreation, than are youth working fewer hours or not at all. Research shows that these unstructured activities increase the likelihood of delinquency, substance use, and other problem behaviors (Osgood 1999; Safron et al. 2001), and indeed, evidence suggests that those youth who work more than 20 hours per week are more likely to engage in delinquency, substance use, and school-related misconduct (Uggen and Wakefield 2008). However, it remains unknown the extent to which these relationships are causal, such that long hours of work cause problem behaviors. As we discuss in more detail below, the alternative explanation is that both long hours and health-risk behaviors have a common cause, such as early disengagement from school or deviant peers (Bachman et al. 2008; Staff et al. 2009).

In addition to understanding causal direction, one needs to attend to potential non-linear effects of paid work on achievement and positive youth development. In fact, evidence is mounting that limited work hours are beneficial, whereas only excessive involvement in paid work is harmful. For instance, longitudinal research on two cohorts from Generation X shows that teenagers who work moderately (i.e., average 20 hours or less per week) during the school year do not spend less time on homework and extracurricular activities than their non-working peers (Schoenhals et al. 1998; Shanahan and Flaherty 2001), and shows greater academic achievement and likelihood of high school completion (Mortimer and Johnson 1998). Other studies have shown potential developmental benefits of paid work with respect to improved health and well-being, the development of responsibility and time-management skills, and improved family relationships (Mortimer 2003; Mortimer et al. 1996; Mortimer and Shanahan 1994). Moreover, in young adulthood, youth who worked moderately over the duration of high school showed higher levels of educational and occupational attainment than their counterparts who worked intensively, or not at all, during the high school years (Carr et al. 1996; Mortimer 2003; Ruhm 1997; Staff and Mortimer 2007). Again, however, the extent to which these relationships are causal is not clear—for example, those who work moderately may already have more initiative and be more organized and future oriented.

One might conclude from the available evidence that youth should avoid intensive work during the school year and only work limited hours. Parents, businesses, and policy-makers could establish sensible policies to restrict work hours for teenagers during the school year. Unfortunately, the story is not this simple. As we review below, an emerging body of research argues that the poor achievement and adjustment evident among intensive workers reflects selection processes and not causal work effects. These spurious arguments question whether youth would indeed benefit from legislative efforts to curb teenage work hours during the school year.

Spurious Arguments

Several researchers have suggested that intensive involvement in paid work may not cause poor achievement or engagement in health-risk behaviors, but instead constitute a syndrome of early adult-like identity formation (Bachman and Schulenberg 1993). Prior engagement in delinquency, such as drinking, having sex, using drugs, and school misconduct, may predispose some youth to enter work environments in which employers and coworkers offer less social constraints on these behaviors than do teachers and parents (Newcomb and Bentler 1988). In fact, longitudinal research on a cohort from Generation X shows that 9th graders with higher rates of problem behaviors (e.g., substance use, school-related deviance, and law violations) reported greater work hours in subsequent years of high school (Mortimer 2003; Staff and Uggen 2003). In a series of papers, Apel et al. (2006, 2007) and Paternoster et al. (2003) found that intensive work has little effect on delinquency, substance use, and other problem behaviors once accounting for these likely sources of spuriousness. Likewise, Rothstein (2007) found that controlling for unobserved individual differences reduced the relationship between intensive hours and GPA to statistical non-significance. These findings may reflect the notion that youth across generations who have less interest or success in school and other extracurricular activities may be drawn to the autonomy, pay, and status that can come from working (Bachman and Schulenberg 1993; Staff and Uggen 2003). Bachman et al. (2003) show that an early desire for intensive work hours (measured before the youth obtained jobs) predates both work involvement and problem behaviors in later adolescence. Thus, the argument here is that hours of work has little independent effect for at least some young people. As noted below, the apparent effects instead reflect other more fundamental causes.

Evidence from the Monitoring the Future Study

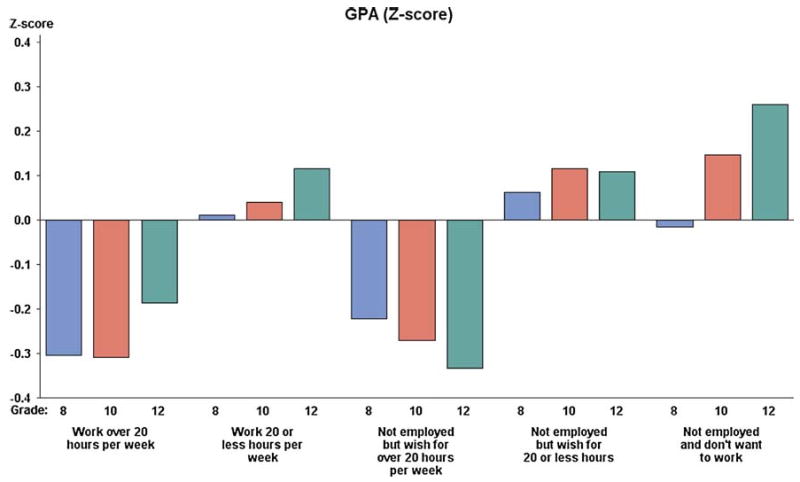

To help illustrate the importance of this spurious argument, Fig. 2 presents mean levels of GPA among working and non-working youth at various ages (i.e., in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades). We display GPA, ranging on a nine-point scale from “D” to “A,” as a z-Score to ease interpretation. For this graph, we included only youth from the Millennial generation (combined cohorts from 1991 to 2006). Similar to most previous research, we distinguished working Millennial youth who were employed intensively (i.e., averaged over 20 hours per week during the school year) from those who worked moderate hours (i.e., 20 hours or less per week). In a series of recent papers, we have argued that it is important to consider the extent to which orientations toward work affect achievement among jobless youth who have a strong desire for work but may lack the opportunity for meaningful employment (Bachman et al. 2003; Staff et al. 2006, 2008). Numerous factors could keep youth from holding desired jobs, such as poor local-labor market conditions, discrimination, obligations to school and family, compulsory school attendance, and age restrictions limiting the hours and type of employment, even if they had a strong desire to work. These preferences for long hours on the job, and not necessarily high-intensity work per se, could affect school achievement and positive youth development (Warren 2002).

Fig. 2.

Grade point average in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades (z-Scores) by actual and preferred work hours: MTF 8th, 10th, and 12th graders (combined cohorts from 1991 to 2006). Source: Staff, J., Schulenberg, J., & Bachman, J. (2008). Explaining the academic engagement and performance of employed youth. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, March 6–9

In the MTF surveys, the preference for work is based upon the question asked of all students: “Think about the kinds of paid jobs that people your age usually have. If you could work just the hours you wanted, how many hours per week would you PREFER to work?” In this example, we assigned non-working youth to one of three mutually exclusive categories based upon their preference for work: (1) non-workers who prefer intensive work (these youth were not employed during the school year but wished they could have worked 20 hours or more per week); (2) non-workers who prefer moderate work (they also averaged 0 hours of paid work during the school year but preferred to work 20 hours or less per week); and (3) non-workers who preferred not to work or who were uncertain.

Figure 2 shows a similar pattern of low achievement among the intensive workers and the non-workers who preferred to work intensively. Both groups of youth from the Millennial generation scored relatively low GPAs in the 8th, 10th, and 12th grades. In contrast, moderate work hours (both actual and preferred) were associated with school success. Students who were jobless and preferred not to work (or were uncertain as to how many hours they would like to work) were similar to youth who were also jobless but preferred to work just a little. Although not shown in Fig. 2, it is important to note that among Millennial youth, only 5% of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the MTF study indicated that they had no desire to work (and less than 1% of employed youth wished they did not have to work).

This simple illustration highlights some important selection issues regarding paid work effects on achievement among young people. Previous research and our example above suggest that Baby Boom, Generation X, and Millennial youth all perform poorly when they both wish to and actually do work long hours. This suggests that poorly performing youth may be selecting more intensive paid work experiences rather than high-intensity work compromising school success. We believe that Fig. 2 also nicely illustrates how work “effects” may be conditioned by preexisting background factors. For instance, actually working moderate hours (compared to non-working and desiring moderate hours) appears to have been more beneficial for older rather than younger youth in the Millennial generation. Likewise, older youth perform worse in school when they wish for long hours on the job (but remain jobless), compared to when they actually work long hours. Younger youth, on the other hand, appear to have the lowest GPAs when they spend long hours on the job.

Returning to the question of how many hours youth should work, the answer is not so simple. Evidence just presented suggests that work motivations can contribute to poor achievement, depending on how much the young person wants to work. For instance, among non-working youth, those who wish they could work long hours had lower grades than those who would prefer to work moderately. Since the motivations for paid work often precede the actual experience of employment (Bachman et al. 2003), some youth may have strong orientations toward work, but are externally constrained from holding a job (e.g., they are too young, they lack a car, they have no prior work experience, etc.). All things considered, desiring to work moderate hours, or actually working moderate hours, may have more benefits than other configurations.

What Types of Jobs are Desirable?

The second question facing youth as they enter paid work is what type of job they should work in. This issue may be especially important among recent cohorts of youth (i.e., Generation Xers and Millennials) because some scholars have suggested that the teenage work experience is worse today than in years past (Greenberger and Steinberg 1986; see also Aronson et al. 1996 for a contrary view). For instance, Greenberger and Steinberg (1986) argued that the majority of teenage jobs, especially those in fast-food restaurants and retail settings, no longer provide skills and workplace knowledge as preparation for adult work, in part because most teenagers work in jobs with no opportunities for meaningful interaction with adult mentors and supervisors (Greenberger 1988). Furthermore, the absence of adults in these workplace settings may heighten the risk of crime and misconduct, such as giving away products, providing free services, fabricating hours on a timecard, or vandalizing company property. In such occupational settings, the workplace is no longer a stepping-stone to future adult roles through mentorship and skill acquisition.

In order to answer the question about what jobs are desirable for young people, we first need to identify the components of a good job. Looking to adult conceptions of good jobs is not especially useful because most young people from recent cohorts (i.e., Generation X and Millennial) work in jobs that involve relatively low pay, limited benefits, and entail work arrangements that are often informal and temporary (Kalleberg et al. 2000). Hirschman and Voloshin (2007) considered employment as lifeguards, athletic coaches, tutors, office clerks, or receptionists as “good jobs” in adolescence because youth who work in these types of jobs earn high wages and often can moderate the number of hours they work per week. Yet past research shows that the conditions of youth work vary substantially across other important dimensions such as its degree of learning opportunities and skill utilization, its demanding and stressful features, and its compatibility with school, family, and friends (Mortimer 2003). Past research also shows that these qualities of paid work affect mental health and problem behaviors during adolescence. For instance, wage satisfaction and the compatibility of paid work with school enhance feelings of well-being, while job stressors increase depressive affect and reduce self-efficacy (Finch et al. 1991; Mortimer et al. 2002). Skill utilization in the workplace fosters both intrinsic and extrinsic occupational values (Mortimer et al. 1996), as well as improves the quality of relationships with parents (Mortimer and Shanahan 1994). Early work qualities have also been shown to affect delinquency and substance use (Staff and Uggen 2003). This research finds that many employment conditions that are valued by adults, such as workplace autonomy, pay, and status, worsen problem behaviors when experienced during adolescence. In contrast, work that is more age-appropriate, with clear linkages to school and with opportunities to learn new skills, reduces delinquency and substance use. Consistent with this point of view, Schulenberg and Bachman (1993) found that youths were less likely to use drugs and alcohol when their early work experiences were connected to future careers and provided opportunities to learn new skills.

Evidence from the Monitoring the Future Study

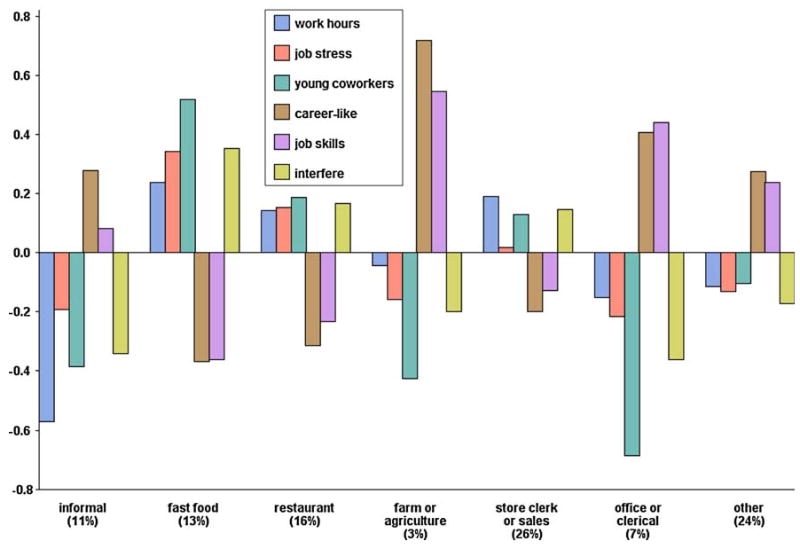

In order to illustrate what types of jobs constitute desirable employment experiences during the teenage years for young people today, we draw upon measures of work quality among employed 12th graders in the MTF dataset. (The MTF project contains limited information regarding the workplace conditions of 8th and 10th graders, so it is not presented here.) Figure 3 shows mean levels of job quality across different types of jobs based upon a combined dataset of 12 cohorts of 12th graders from 1995 to 2006 (encompassing Generation X and Millennial youth). The self-reported measures of job quality indicate the extent to which the 12th grader's current job: (1) causes stress and tension; (2) interferes with education, family, or social life; (3) uses their skills and abilities, makes good use of their special skills at work, and provides them opportunities to learn new skills; (4) is comprised of teenage coworkers; and (5) is a career-like job. We also included a measure of the average number of hours they worked during the school year. Again, we display each of these variables as z-Scores to ease interpretation.

Fig. 3.

Dimensions of work quality (z-Scores) in the 12th grade by job type: MTF 12th graders only (combined cohorts from 1995 to 2006). Source: Staff, J., Messersmith, E. E., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2009). Adolescents and the world of work. In R. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., pp. 270–313). New York: John Wiley & Sons

We then coded job type into seven categories: (1) informal jobs (e.g., babysitting, newspaper delivery, yard maintenance, and odd jobs); (2) fast-food jobs; (3) restaurant jobs (e.g., waiters and waitresses, cooks); (4) farm and agriculture jobs; (5) sales and retail jobs; (6) office or clerical positions; and (7) other jobs. Figure 3 shows the percentage of 12th grade workers in each occupational category.

As shown in Fig. 3, of the seven job types, fast-food workers (comprising 13% of employed 12th graders) rate poorly across the work quality dimensions. For instance, fast-food workers report the highest levels of job stress and job interference with school, family, and friends. Youth in fast-food settings also work with young coworkers and are unlikely to indicate that their job provides skills or is a “career-like” job. Youth employed as store clerks and in sales positions, which are the most typical among the young workers, report high levels of job stress, low levels of job skills and career potential, and interference with school, friends, and families. The most desirable jobs appear to be in office and clerical positions (8% of workers), as youth in these jobs report low job stress, older coworkers and supervisors, little interference with school and family roles, and ample opportunities to learn new skills or build a career.

Compared to prior generations, Generation X and Millennial youth are much less likely to work in agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, and even the service industry (National Research Council 1998). Instead, youth today are increasingly likely to work in department stores, grocery stores, restaurants, and retail stores (see the U.S. Department of Labor 2000). Importantly, one-third of working teenagers today are employed in eating and drinking establishments, and as we show above, these jobs often entail young coworkers and supervisors, job stress, and interference with family, friends, and school.

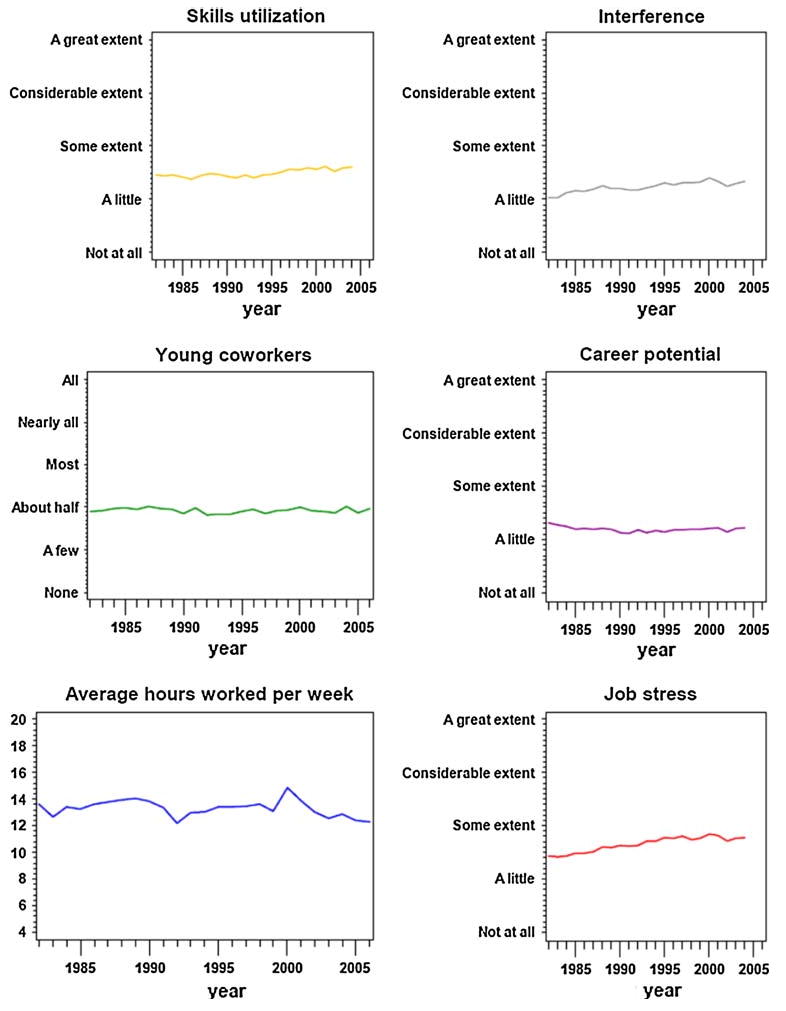

However, although we show in this example some differences in how youth rate different types of jobs, it should also be noted that overall, employed youth were generally positive about their early work experiences. In order to illustrate this point, Fig. 4 displays the average values of the work quality dimensions for nearly a quarter of a century (from 1982 to 2006, including Baby Boomers, Generation Xers, and Millennials). For instance, on average, employed youth experienced job stress “to some extent” and “a little” interference with family, school, and friends. Employed youth also used their job skills “to some extent,” reported that their jobs had “a little bit” of career potential, and said about half of their coworkers were within two or three years of their own age. What is especially striking in Fig. 4 is how little these dimensions of work quality have changed in the past 25 years; Baby Boomers, Generation Xers, and Millennials responded in largely the same way to the same questions at the same age. Moreover, as we had previously shown, the average hours of employment among working 12th graders has changed very little in the past 30 years. Thus, Baby Boomers, Generation Xers, and Millennials have all worked about the same number of hours at the same age.

Fig. 4.

Dimensions of work quality in the 12th grade from 1982 to 2006: MTF 12th graders only (combined cohorts from 1982 to 2006)

Conclusion and Future Directions

Overall, there has been little change in youth work patterns over three generations, from Baby Boomers to Generation Xers to Millennials. Our aim in this article was to highlight some key questions facing youth today as they enter the world of work, regarding work intensity and job type. Previous research leads us to conclude that youth should limit the hours they devote to work during the school year and perhaps aim to work in an office or clerical-type position. In the general case, this would be the “ideal” job for today's teenager.

Nevertheless, as we have shown in our previous study, as well as demonstrate in the example above, work motivations can also contribute to poor achievement depending on how much the young person wants to work. This suggests that work hours may have little independent effect for at least some young people (Staff et al. 2006, 2008). The desire for employment among youth is a useful way to disentangle causal versus spurious effects of work on youth achievement and adjustment. We also highlighted some of the factors that lead youth into work of varying hours, duration, and quality, and at the same time keep them from holding desired types of jobs and levels of intensity.

Against this backdrop, it is important to specify the conditions under which the effects of teenage work hours on social development vary by gender, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic background. Young people from more or less advantaged backgrounds may have varying conceptions of what are “intensive” and “moderate” work investments during the school year. Moreover, the perceived quality of jobs may also vary by these sociodemographic characteristics. For example, although fast-food work, on average, is associated with poor work quality in Fig. 3, youth in poor neighborhoods often must find jobs in a limited and competitive labor market. In such settings, work in fast-food restaurants can link teenagers with older adults in the community and foster positive social development (Newman 1999). In contrast, youth residing in more affluent neighborhoods may find numerous employment opportunities and thus may have little stake in even high quality office and clerical positions.

Given the findings we highlight in this article, an obvious recommendation for future research is to attend to the type of work experiences when examining the possible positive and negative effects of paid work on adolescent development. Past studies overwhelmingly focus on the hours of work and devote very little attention to different types of jobs and qualities of work experience (National Research Council 1998). Although work intensity is an important dimension of adolescent work experience, it is clearly not the only one and may not even be the most important one (Staff et al. 2009). By examining work intensity exclusively as a main effect, the extant literature may be missing the complex realities of adolescent work experience whereby hours of work serve largely to moderate the effects of the type and quality of work. By focusing more on types and qualities of jobs, more can be gained in terms of understanding for whom and under what conditions teenage work does provide benefits for and detriments to optimal development.

Despite some unanswered questions, we can tentatively reach the following conclusion regarding the relationship between paid work and youth development: moderate work hours, especially in jobs of higher quality, are associated with a broad range of positive developmental outcomes. We are hesitant to discourage all youth from working intensively, or from avoiding jobs that are not office and clerical positions, as even high-intensity work in fast-food jobs has been shown to be beneficial for some young people. Future research will help provide better answers about the conditions and benefits of high quality work in adolescence for subsequent generations of youth.

Acknowledgments

The first author gratefully acknowledges support from a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award in Population Research from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01 HD054467). This paper uses data from the Monitoring the Future study, which is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA01411); the second author gratefully acknowledges support from this grant. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsors. We also wish to acknowledge our coauthors on several related projects that we describe in this review: Jerald G. Bachman, Emily Messersmith, D. Wayne Osgood, and Michael Parks.

Footnotes

A previous version of this manuscript was presented at the annual meeting of the 2008 American Sociological Association.

Contributor Information

Jeremy Staff, Email: jus25@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, The Pennsylvania State University, 211 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207, USA.

John E. Schulenberg, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

References

- Apel R, Bushway S, Brame R, Haviland AM, Nagin DS, Paternoster R. Unpacking the relationship between adolescent employment and antisocial behavior: A matched samples comparison. Criminology. 2007;45(1):67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Apel R, Paternoster R, Bushway S, Brame R. A job isn't just a job: The differential impact of formal versus informal work on adolescent problem behavior. Crime and Delinquency. 2006;52(2):333–369. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson PJ, Mortimer JT, Zierman C, Hacker M. Generational differences in early work experiences and evaluations. In: Mortimer JT, Finch M, editors. Adolescents, work, and family: An intergenerational developmental analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE. The education–drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates/Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Safron DJ, Sy SR, Schulenberg JE. Wishing to work: New perspectives on how adolescents' part-time work intensity is linked with educational disengagement, drug use, and other problem behaviours. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27(4):301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. How part-time work intensity relates to drug use, problem behavior, time use, and satisfaction among high school seniors: Are these consequences or merely correlates? Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Carr RV, Wright JD, Brody CJ. Effects of high school work experience a decade later: Evidence from the national longitudinal study. Sociology of Education. 1996;69(1):66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. Early work histories of urban youth. American Sociological Review. 2000;65(2):279–297. [Google Scholar]

- Finch MD, Shanahan MJ, Mortimer JT, Ryu S. Work experience and control orientation in adolescence. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(5):597–611. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E. Working in teenage America. In: Mortimer JT, Borman KM, editors. Work experience and psychological development through the life span. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1988. pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Steinberg LD. When teenagers work: The psychological and social costs of teenage employment. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C, Voloshin I. The structure of teenage employment: Social background and the jobs held by high school seniors. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2007;25(3):189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007 Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No 08-6418A) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007 Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIH Publication No 08-6418B) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg AL, Reskin BF, Hudson K. Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. American Sociological Review. 2000;65(2):256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Staff J. When work matters: The varying impact of adolescent work intensity on high school drop-out. Sociology of Education. 2007;80(2):158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Light A. In-school work experience and the returns to schooling. Journal of Labor Economics. 2001;19(1):65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Kleitman S. Consequences of employment during high school: Character building, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal. 2005;42(2):331–369. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT. Working and growing up in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Finch MD, Ryu S, Shanahan MJ, Call KT. The effects of work intensity on adolescent mental health, achievement, and behavioral adjustment: New evidence from a prospective study. Child Development. 1996;67(3):1243–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Harley C, Staff J. The quality of work and youth mental health. Work and Occupations. 2002;29(2):166–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Johnson MK. New perspectives on adolescent work and the transition to adulthood. In: Jessor R, editor. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ. Adolescent work experience and family relationships. Work and Occupations. 1994;21(4):369–384. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Youth at work: Health, safety, and development of working children and adolescents in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of adolescent drug use: Impact on the lives of young adults. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Newman KS. No shame in my game. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. and the Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW. Having the time of their lives: All work and no play? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Shanahan MJ, editors. Transitions to adulthood in a changing economy: No work, no family, no future? Westport, CT: Praeger; 1999. pp. 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R, Bushway S, Brame R, Apel R. The effect of teenage employment on delinquency and problem behaviors. Social Forces. 2003;82(1):297–336. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein DS. High school employment and youths' academic achievement. The Journal of Human Resources. 2007;42(1):194–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ. Is high school employment consumption or investment? Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15(4):735–776. [Google Scholar]

- Safron DJ, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Part-time work and hurried adolescence: The links among work intensity, social activities, health behaviors, and substance use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(4):425–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhals M, Tienda M, Schneider B. The educational and personal consequences of adolescent employment. Social Forces. 1998;77(2):723–762. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Hours on the job? Not so bad for some types of jobs: The quality of work and substance use, affect and stress. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development; New Orleans, LA. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Flaherty BP. Dynamic patterns of time use in adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72(2):385–401. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Messersmith EE, Schulenberg JE. Adolescents and the world of work. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 270–313. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Mortimer JT. Educational and work strategies from adolescence to early adulthood: Consequences for educational attainment. Social Forces. 2007;85(3):1169–1194. doi: 10.1353/sof.2007.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Osgood DW, Schulenberg J, Bachman J, Messersmith E. Explaining the relationship between employment and juvenile delinquency. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; November 1–4; Los Angeles. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Schulenberg J, Bachman J. Explaining the academic engagement and performance of employed youth. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; March 6–9.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Uggen C. The fruits of good work: Early work experiences and adolescent deviance. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40(3):263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen C, Wakefield S. What have we learned from longitudinal studies of work and crime? In: Liberman A, editor. The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 191–219. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Report on the youth labor force. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JR. Reconsidering the relationship between student employment and academic outcomes: A new theory and better data. Youth and Society. 2002;33(3):366–393. [Google Scholar]