Quality of Life among Children with Velocardiofacial Syndrome (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Jul 5.

Published in final edited form as: Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010 May;47(3):273–283. doi: 10.1597/09-009.1

Abstract

Objective

To explore health related quality of life (QoL) among children with velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS), and to compare QoL by gender and with samples of chronically ill and healthy children.

Design and Setting

Parents of children with VCFS completed a written survey mailed to the home.

Participants

Parents of 45 children ages 2 to 18 years with VCFS participated in this study, and their findings were compared to published data on the same measures from samples of parents of healthy children (n = 10,343) and children with a variety of chronic conditions (n = 683).

Main outcome measures

QoL, including fatigue, was measured using the PedsQL™ Measurement Model. Strengths were assessed by parent report from a list of character traits developed from the Values in Action Classification system.

Results

QoL was generally lower across all domains compared to healthy children. Boys with VCFS scored significantly lower than girls on school functioning and cognitive fatigue. Compared to children with chronic conditions, children with VCFS scored lower on emotional, social, and school functioning, but not on physical health. Parents consistently described their children's strengths as humor, caring, kindness, persistence, and enthusiasm.

Conclusions

QoL among children with VCFS is characterized by significant challenges in the cognitive, social, and emotional domains. On the other hand, parents of these children describe them as having strengths that may be useful in coping with the daily challenges of this condition.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion, QoL, velocardiofacial syndrome

Velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS), also known as DiGeorge syndrome or 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, is a multianomaly genetic condition with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4000 live births (Murphy & Scambler, 2005; National Library of Medicine, 2007). VCFS is caused by a microdeletion of chromosome 22q11.2 detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing (Driscoll et al., 1992; Scambler et al., 1992). Individuals affected by VCFS face numerous physical and psychosocial challenges across the life span. The physical and cognitive issues associated with VCFS have been relatively well described in the literature. What is currently known about VCFS will be furthered by an increased understanding of the quality of life (QoL) of children with this condition. Research that incorporates a comprehensive perspective of health and well-being can be used to guide health care of children and inform pediatric health policy (Matza, Swensen, Flood, Secnik, & Leidy, 2004). The purpose of this study was to explore health related quality of life (QoL) among children with VCFS, and to compare QoL by gender and with samples of chronically ill and healthy children.

Background

Quality of Life and VCFS

Advances in pediatric health care have greatly improved the life expectancy of children born with conditions once considered to be terminal (Newacheck et al., 2008). These advances have broadened the focus of pediatric health care beyond the physical care of the child to consider the child's health-related QoL (Eiser & Morse, 2001; Quittner, Davis, & Modi, 2003). Researchers agree that QoL is a multidimensional, subjective concept and most definitions include physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains (Vallerand & Payne, 2003). To date, most studies of health-related QoL have examined the physical dimensions of health for children with chronic conditions such as asthma (Gibson, Henry, Vimpani, & Halliday, 1995), cancer (Goodwin, Boggs, & Graham-Pole, 1994; Varni, Katz, & Seid, 1998), cystic fibrosis (Havermans, Vreys, Proesmans, & DeBoeck, 2006; Modi & Quittner, 2003), and epilepsy (Keene, Higgins, & Ventureyra, 1997; Wildrick, Parker-Fisher & Morales, 1996). Researchers have also explored QoL among individuals with craniofacial conditions such as Moebius syndrome (Meyerson, 2001) and congenital and acquired facial differences such as cleft lip and palate and burns (Locker, Jokovic, & Tompson, 2005; Topolski, Edwards, & Patrick, 2005). Findings of these studies are varied but generally support the notion that QoL is an important consideration in the holistic assessment of individuals with chronic health conditions. As a construct, health-related QoL can help to translate an individual's experience of illness into a quantifiable outcome (Stade, Stevens, Ungar, Beyene, & Koren, 2006). As an outcome variable, QoL can help clinicians and researchers determine the efficacy of interventions designed to improve the lives of individuals with acute and chronic health conditions.

QoL among children with chronic conditions such as VCFS is affected by a complex interaction of factors. Compared with healthy children, children with chronic health conditions experience lower levels of physical, emotional, social, and school functioning (Wallander & Varni, 1998). A child's level of function in these four domains – physical, emotional, social, and school – contributes significantly to that child's overall well-being and QoL. Though separate entities, each of these domains interacts dynamically with the others (Ferrell & Grant, 2003). Decreased physical function, for example, may limit a child's ability to participate in recreational activities, which in turn may affect one's social and emotional function. Difficulties with fatigue, both physical and cognitive, may impact a child's ability to keep up with peers in school, further affecting one's relationships socially and emotionally. Physical well being also has a direct impact on spirituality (Ferrell and Grant), and struggling with the meaning of one's illness and the ability to transcend uncertainty has an important role in QoL. For the purpose of this study, QoL is defined in the context of VCFS as the child's: 1) level of function in four domains (physical, psychological, social, and school); 2) level of fatigue; and 3) spiritual well-being.

Functional status

Several physical features of VCFS have the potential to impact a child's overall function and QoL. Individuals with VCFS have a range of physical findings, often including congenital heart disease, palatal abnormalities, hypocalcemia, immune deficiency, and characteristic facial features (McDonald-McGinn, Emanuel, & Zackai, 2005). Additional findings include: significant feeding problems, renal anomalies, hearing loss, growth hormone deficiency, autoimmune disorders, seizures, and skeletal abnormalities (McDonald-McGinn, Emanuel, & Zackai). Gross and fine motor delays are also common among children VCFS (Van Aken et al., 2007). Many of these physical manifestations of VCFS have the potential to directly and significantly alter a child's QoL. Conotruncal defects consisting of anomalies of the outflow tract of the heart, for example, can lead to cyanosis and fatigue with a diminished tolerance for activity. Children with VCFS who have immunodeficiency are more susceptible to infections such as otitis media and recurrent bronchitis (Sullivan, 2005), placing the child at risk for hearing loss as well as poorer overall health. Palatal anomalies may affect an infant's ability to feed, which may lead to growth failure and decreased functional status, as well as cause difficulties with speech.

The primary psychological manifestations of VCFS include difficulties with anxiety, cognitive function, and attention. Children with VCFS have demonstrated higher prevalence rates of major depressive disorder, simple phobias, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Antshel et al., 2006). Campbell and Swillen (2005) suggest that there may be a cognitive profile characteristic of individuals with VCFS that is independent of associated medical conditions such as cardiac and palatal anomalies. A wide range of cognitive abilities have been found, often with a discrepancy between verbal and non-verbal IQ scores (Antshel, AbdulSabur, Roizen, Fremont, & Kates, 2005; Swillen et al., 1997). Children with VCFS tend to perform well in “rote” verbal memory, with more difficulties in the area of visual spatial memory, consistent with the pattern of cognitive impairment in nonverbal learning disability (Campbell & Swillen). The implications of this psychological profile on QoL may be greatest in the educational environment, where children are expected to comprehend instructions and process new and increasingly complex material as they advance academically.

The ability to communicate and interact socially with others is a significant factor in one's social well-being. Speech and language difficulties comprise one of the most distressing aspects for most parents of children with VCFS, and can significantly affect the quality of the child's life (Kobrynski & Sullivan, 2007). Difficulties can include velopharyngeal dysfunction with hypernasal speech, articulation disorders, motor speech disorders, expressive and receptive language deficits and pragmatics deficits (Kummer, Lee, Stutz, Maroney, & Brandt, 2007; Scherer, D'Antonio, & Kalbfleisch, 1999; Solot 2000). As with individuals with craniofacial differences, many children with VCFS have visible facial differences that may affect peer interactions and relationships, and thus may experience stigmatization that can negatively impact a child's QoL (Topolski, Edwards, & Patrick, 2005).

Fatigue

While it is a normal experience for healthy individuals, fatigue may be experienced differently by individuals with illness. Whereas healthy adults describe it as temporary, relaxing, normal, and pleasant, individuals with chronic conditions have described fatigue as frustrating, exhausting, and frightening (Gielissen et al., 2007). Fatigue is defined clinically as a decline in performance during sustained activity, and can be associated with performance on both motor and cognitive tasks (Schwid et al., 2003). When fatigued, an individual's performance declines unless the individual increases the amount of effort expended. This has a significant impact on one's QoL in that it requires an individual to work harder than others to perform tasks required for daily life as well as recreational and social activities. In cognitive fatigue, according to DeLuca et al. (2008) performance declines when sustained attention is required unless there is increased brain activation. Difficulty sustaining attention – also known as “vigilance decrement” (Pattyn, Neyt, Henderickx, & Soetens, 2008) – is a manifestation of cognitive fatigue and affects QoL by limiting one's participation in social or educational activities. Fatigue as a component of QoL among children with VCFS has not been specifically described in the literature; however, low muscle tone, cardiac anomalies, and attention difficulties may contribute to physical and cognitive fatigue in children with VCFS.

Spiritual well-being

Spiritual well-being is influenced by a number of factors, including the ability to find meaning in one's situation, the ability to maintain hope in the face of challenges, and one's inner strength (Vallerand & Payne, 2003). An important consideration in the spiritual domain of QoL for children with VCFS is the extent to which an individual is self-directed, capable of engaging cooperatively in self–other relationships, and capable of ‘transcending self’ in understanding one's place or purpose in the larger social context (Constantino, Cloninger, Clarke, Hashemi, & Przybeck, 2002). In this sense, spiritual well-being may manifest through strengths of character. The Values in Action project (Park & Peterson, 2005), an organization based on advancing principles of positive psychology, stresses the importance of strengths of character that contribute to optimal human development. According to the Search Institute (2006), internal developmental assets, such as integrity, self-regulation, and interpersonal skills, work with external developmental assets, such as family support, safety, and positive peer relationships, to promote well-being in children. Further, the more assets children have, the more likely they will report having positive attitudes and behaviors (Search Institute). Stable elements of character may be determined by genetic factors and experiences that occur before the age of 2 years (Constantino, Cloninger, Clarke, Hashemi, & Przybeck, 2002). There is some evidence for a unique profile of character strengths among individuals with similar genetic makeup and biological mechanisms. Children with ADHD, for example, have been found to have higher levels of novelty seeking and self transcendence relative to healthy controls (Cho et al., 2008). While there is some evidence for a behavioral phenotype in VCFS (Murphy, 2004), a unique profile of character strengths in VCFS has not been explored.

Gender Differences

While the current literature on QoL does not explicitly address the role of gender, gender plays an important role in child development and functioning. Research in developmental disorders has suggested that girls with developmental delays are generally less adversely affected than boys (e.g. Antshel, AbdulSabur, Roizen, Fremont, & Kates, 2005; Volkmar, Szatmari, & Sparrow, 1993). In general, boys acquire language later, have more reading problems, and smaller vocabularies than girls (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008). Boys are more likely to have early-onset disorders such as developmental language disorders and ADHD, whereas girls are more likely to have adolescent-onset emotional disorders such as mood disorders and eating disorders (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau). Boys tend to be more likely than girls to have a special health care need concurrently with a physical, developmental, behavioral/conduct, or emotional condition (Newacheck, Kim, Blumberg, & Rising, 2008).

Gender differences have been described among children with VCFS as well. Relative to boys with VCFS, girls with VCFS may be less cognitively affected, although age is negatively associated with cognitive functioning in girls with VCFS but not boys (Antshel, AbdulSabur, Roizen, Fremont, & Kates, 2005). Antshel et al. (2005) suggested that VCFS gender differences may be most significant in the nonverbal domain. DeSmedt et al. (2007), on the other hand, found no evidence for an association between cognitive function and child gender among children with VCFS. Gender differences in cognitive function among children with VCFS have been explored in the literature, however, there has yet to be an examination of the potential implications of these differences on QoL for boys and girls with VCFS.

Purpose of the Study

The measurement of QoL provides valuable information regarding the interaction of the biological, psychological, social and spiritual impact of a condition and its treatment on children, especially where no differences in survival rates are anticipated (Clarke & Eiser, 2004). However, research on VCFS to date has focused on the constellation of physical and cognitive challenges faced by these children and their families. While the implications of VCFS on a child's QoL is undoubtedly important, no research to date has been conducted to document the health related QoL for children with VCFS. In addition, despite evidence for a gender difference in the presentation and effects of VCFS, little is known about the differential effects on QoL for boys and girls with VCFS. Finally, there is need for a strength-based approach to children with VCFS so that interventions can be tailored to children's unique strengths. The purpose of this study was (1) to describe health related QoL among children with VCFS as reported by parents, as well as (2) determine whether QoL among children with VCFS differs by gender, (3) determine whether QoL scores of children with VCFS differ from QoL scores of healthy children and other children with chronic conditions, and (4) to describe a profile of strengths identified among children with VCFS.

Method

Participants

Participants were parents (n = 45) of children with VCFS ages 2 to 18 years. All of the children were diagnosed with VCFS by genetic testing with FISH prior to participating in this study. Parents were recruited by distributing informational brochures about the study to parents of children with VCFS in clinical settings (cleft and craniofacial clinics) and by mail. Brochures included a stamped, addressed postcard that the parent could return to indicate an interest in participating in the study. A website was also established to provide information to potential participants. The website included a page on which parents could send a message to the researcher indicating an interest in participating. Parents who indicated an interest in participating in the study were enrolled. One parent and one child per household are represented in this sample. Families with more than one child with VCFS were asked to consider one child when responding to the survey. Most (96%) of the respondents were female; 89% of respondents identified themselves as the child's biological parent, 7% as adoptive parents, and 4% as “other”. Eighty-four percent of respondents were married, and the remainder were widowed, divorced, separated, or never married. Approximately half (51%) of the children were male. All but 2% of the parent respondents are White, and 91% of the children are White (the remainder were identified as multiracial). Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Parent and Child Descriptives.

| Range | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Child age in years | 2.3 – 18.75 | 8.9 (4.3) |

| Child age at diagnosis (VCFS), in years | 0 – 14.1 | 3.1 (3.3) |

| Parent age in years | 25.0 – 53.0 | 38.8 (6.1) |

| Highest level of Education (parent) | n (%) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 3 (6.7) | |

| Vocational school/some college | 5 (11.1) | |

| College degree | 27 (60.0) | |

| Professional or graduate degree | 10 (22.2) | |

| Household Income (annual) | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 8 (17.8) | |

| 50,000to50,000 to 50,000to75,000 | 12 (26.7) | |

| 75,001to75,001 to 75,001to100,000 | 11 (24.4) | |

| $100,001 or more | 11 (24.4) | |

| Missing | 3 (6.7) | |

| Child receives special education services | 34 (75.6) | |

| Category of special education services* | ||

| Speech/Language Impaired (SLI) | 19 (42.2) | |

| Developmental/Cognitive Disability | 6 (13.3) | |

| Deaf/Hard of Hearing | 1 (2.2) | |

| Specific Learning Disability | 3 (6.7) | |

| Emotional Behavioral Disorder | 4 (8.9) | |

| Developmental Delay | 9 (20.0) | |

| Other Health Disability | 16 (35.6) |

Data for comparison groups

Data on general quality of life for healthy children are from a statewide population sample of 10,241 families with healthy children ages 2 to 18 years who were new enrollees in California's State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in 2001 (Varni, Burwinkle, Seid, & Skarr, 2003). Data on fatigue for healthy children are from a study in which 102 parents of children ages 2 to 18 years were recruited from a list of patients who had attended an orthopedic clinic and had been deemed healed from injuries (Varni, Burwinkle, & Szer, 2004). Data on children with chronic conditions are from a study designed to document the psychometric properties of the PedsQL™ across several pediatric populations (Varni, Seid, & Kurtin, 2001). The children with chronic conditions (n = 683) were ages 2 to 18 years and were recruited from primary care, specialty, and outpatient community clinics.

Measures

Several existing measures and demographic items were compiled into a single survey booklet, the 22qFamilyMatters Survey, for a larger study of children with VCFS. For this study, three measures were used to assess QoL, fatigue, and strengths. For all measures, parent proxy report was used. In general, parents have been found to be reliable reporters of their child's QoL (Stade, Stevens, Ungar, Beyene, & Koren, 2006).

Quality of life: function

Function was measured using the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales developed by Varni. The PedsQL™ core scales have demonstrated utility in evaluating health-related QoL for children with heart defects (Walker, Temple, Gnanapragasam, Goddard, & Brown, 2002), oral clefts (Damiano et al., 2007), and neurological disorders (Meeske, Patel, Palmer, Nelson, & Parow, 2007; Varni, Limbers, & Burwinkle, 2007), and has repeatedly been shown to be reliable and valid for children who are as young as 2 years and have chronic health conditions (Varni, Limbers, & Burwinkle). The measure has been used widely and has evidence of discriminant validity (Varni, Seid, & Kurtin, 2001). The developers of the tool have demonstrated that when differences in scores are reported across chronic health condition and healthy groups, these differences are more likely real differences in self-perceived health-related QoL for the groups studied, rather than differences in interpretation of the items as a function of health status (Limbers, Newman, & Varni, 2008). Among children with chronic health conditions, those with lower physical functioning scores on the PedsQL™ measure have been shown to account for a disproportionately large share of healthcare costs over a 24-month period (Seid, Varni, Segall, & Kurtin, 2004).). The PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales demonstrate factorial invariance for child self-report across individual age groups and across mode of administration (telephone, in-person paper-and-pencil, and mail modes of administration) (Limbers, Newman, & Varni).

The 23-item measure includes items in four domains: Physical Health (8 items), Emotional Functioning (5 items), Social Functioning (5 items), and School Functioning (5 items). Response options are in Likert format (0 = never a problem; 1 = almost never a problem; 2 = sometimes a problem; 3 = often a problem; 4 = almost always a problem). Items are reverse-scored and linearly transformed items to a 0-100 scale (0 = 100; 1 = 75; 2 = 50; 3 = 25; 4 = 0) so that higher scores indicate better health related QoL. Scale scores are computed as the sum of the items divided by the number of items answered to account for missing data. If more than half of the items in the scale are missing, the scale score is not computed.

Quality of life: fatigue

Fatigue was measured using the PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale (Varni, Burwinkle, Katz, Meeske, & Dickinson, 2002), which contains 18 items and comprises three subscales: General Fatigue (6 items), Sleep/Rest Fatigue (6 items), and Cognitive Fatigue (6 items). This instrument was developed based on research and clinical experiences in pediatric chronic health conditions, a review of literature on adult and pediatric fatigue, focus groups, and field testing (Varni, Burwinkle, & Szer, 2004). Response options, item scoring and Scale scores are the same as for the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales.

Character strengths

Because the PedsQL measurement model does not include items in the spiritual domain of QoL, we included a section in the survey to assess the parent's perception of the child's inner strengths. A set of terms that describe character strengths was developed based on the work of Park and Peterson (2005), who created the Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths. The VIA focuses on the strengths of character that contribute to optimal human development. The VIA Classification system identifies 24 character strengths organized under six broad categories. For this study, we tailored this list to enable an efficient way for parents to describe the positive aspects of their children. The final list contains 18 terms; examples are listed in Table 2. Respondents were presented with the list of characteristics with the following instructions: “Below is a list of characteristics of individuals. Please circle one or more of the traits that are strengths for your child.”

Table 2. Domains and Examples of Character Strengths, Based on the Values in Action Inventory*.

| Domain | Description | Examples of Traits |

|---|---|---|

| Wisdom and Knowledge | Cognitive strengths that entail the acquisition and use of knowledge | CuriosityLove of Learning |

| Courage | Emotional strengths that involve the exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of opposition, external or internal | EnthusiasmHonesty |

| Humanity | Interpersonal strengths that involve tending and befriending others | CaringCompassion |

| Justice | Civic strengths that underlie healthy community life | FairnessLoyalty |

| Temperance | Strengths that protect against excess | Modesty |

| Transcendence | Strengths that forge connections to the larger universe and provide meaning | GratitudeHumor |

Procedures

Approval for the use of human subjects in research was obtained from the institutions (children's hospitals) through which parents were recruited. A consent information sheet was included with the survey, with a statement noting that consent would be implied if the respondent competed and returned the survey. Surveys were mailed to parent's homes using the Tailored Design Method (TDM, Dillman, 2000). This method includes sending a pre-letter and strategically-timed post-letters, including a small stipend with the survey, and using stamped return envelopes for mailings. A resource page with contact information was provided in case parents felt a need to speak with someone about the experience of completing the survey; none of the respondents used this resource. Of the 56 surveys sent, 45 (80.4%) were completed and returned.

Analysis

Data were assessed for outliers and variations from normality. In order to confirm that differences by gender were not confounded by group differences in age or time since diagnosis, independent samples t-tests were used to determine whether age at diagnosis or number of years since diagnosis differed by gender. Internal consistency reliability was determined by calculating Cronbach's coefficient alpha for each subscale to determine appropriateness of group comparisons with these data. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare PedsQL™ Generic Core Scales and Multidimensional Fatigue Scales for the VCFS sample with healthy child norms and published means for children with chronic conditions. Strengths were analyzed using descriptive statistics to examine the frequency that each trait was endorsed by respondents. Post-hoc exploratory analyses are described below.

Results

Age at diagnosis (M = 3.07 years, SD = 3.30), and number of years that had passed since the diagnosis (M = 6.66, SD = 3.31) were not significantly different by gender, so age was not included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. Internal consistency reliability for the Peds QL™ Physical Health (α = 0.88), Emotional Functioning (α = 0.81), Social Functioning (α = 0.80), and School Functioning (α = 0.71) scales were acceptable for group comparisons. Internal consistency reliability for the General Fatigue (α = 0.80), Sleep/Rest Fatigue (α = 0.71), and Cognitive Fatigue (α = 0.95) scales were also acceptable for group comparisons.

Quality of Life among children with VCFS

Functional status and fatigue

In general, QoL scores among children with VCFS in this sample were low, with the lowest scores in the school functioning and cognitive fatigue domains. The mean Core Scale scores for functioning were 66.61 (SD = 23.61) for physical health, 62.93 (SD = 20.25) for emotional functioning, 65.07 (SD = 19.96) for social functioning, and 44.55 (SD = 55) for school functioning. Among the scores on the Fatigue Scales, where higher scores indicate less fatigue, scores for cognitive fatigue (M = 44.23, SD = 24.48) were lowest and scores for sleep/rest fatigue (M = 77.75, SD = 16.69) were highest. A post-hoc exploratory analysis was conducted to determine whether functioning and fatigue scores were influenced by the presence or absence of a heart defect or learning disability. QoL and fatigue scores for children whose parents reported a heart condition (murmur and/or anomaly) did not significantly differ from those without a heart condition. Children with a learning disability differed only on the general fatigue scale, with significantly lower scores than children whose parents did not indicate a learning disability was present.

Group Comparisons

Boys' and girls' scores are presented in Table 3. Boys' scores on school functioning (M = 39.42, SD = 15.83) were significantly lower than girls' (M = 51.88, SD = 17.96), (p < .05). Boys' scores on cognitive fatigue (M = 33.18, SD = 19.01) were also significantly lower than girls' scores (M = 56.38, SD = 24.43), indicating less cognitive fatigue in girls (p < .01). Based on item-level comparisons, boys' scores were lower than girls' on all items in this domain, but the significant gender differences in school functioning were limited to two items related to paying attention in class and keeping up with schoolwork. Gender differences in the cognitive fatigue domain were present on all items of this subscale, with the greatest difference on the attention item. On this item, boys' scores (M = 26.09, SD = 15.95) were significantly lower than girls' (M = 54.55, SD = 26.32) at p < .001 (Table 3). These differences persisted in post hoc analyses comparing school functioning and cognitive functioning scores for only those children ages five and older.

Table 3. Scale Descriptives for Quality of Life and Fatigue among Boys and Girls with VCFS.

| Measure | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Scalesa | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD |

| Physical Health | 23 | 69.10 | 24.21 | 22 | 64.00 | 23.25 |

| Emotional Functioning | 23 | 59.78 | 17.50 | 22 | 66.21 | 22.72 |

| Social Functioning | 22 | 61.55 | 19.89 | 21 | 68.75 | 19.83 |

| School Functioning (subscale items listed below) | 20 | 39.42 | 15.83 | 14 | 51.88* | 17.96 |

| Paying attention in class | 20 | 22.50 | 19.70 | 15 | 51.67*** | 24.03 |

| Forgetting things | 19 | 31.58 | 26.14 | 15 | 40.00 | 31.05 |

| Keeping up with schoolwork | 19 | 30.26 | 21.38 | 12 | 50.00* | 30.15 |

| Missing school because of not feeling well | 20 | 60.00 | 29.69 | 15 | 63.33 | 29.68 |

| Missing school to go to the doctor or hospital | 20 | 52.50 | 25.52 | 16 | 54.69 | 24.53 |

| Fatigue Scalesb | ||||||

| General Fatigue | 22 | 62.39 | 16.48 | 22 | 67.46 | 20.15 |

| Sleep/rest Fatigue | 23 | 76.99 | 17.54 | 21 | 78.57 | 16.10 |

| Cognitive Fatigue | 22 | 33.18 | 19.01 | 20 | 56.38** | 24.43 |

| Difficulty keeping his/her attention on things | 23 | 26.09 | 15.95 | 22 | 54.55*** | 26.32 |

| Difficulty remembering what people tell him/her | 22 | 30.68 | 23.06 | 20 | 50.00* | 29.25 |

| Difficulty remembering what he/she just heard | 20 | 34.09 | 22.55 | 20 | 53.75* | 30.65 |

| Difficulty thinking quickly | 21 | 29.76 | 25.76 | 20 | 56.25** | 27.95 |

| Trouble remembering what he/she was just thinking | 20 | 43.75 | 26.75 | 15 | 70.00** | 30.18 |

| Trouble remembering more than one thing at a time | 20 | 28.75 | 23.33 | 18 | 55.56** | 31.57 |

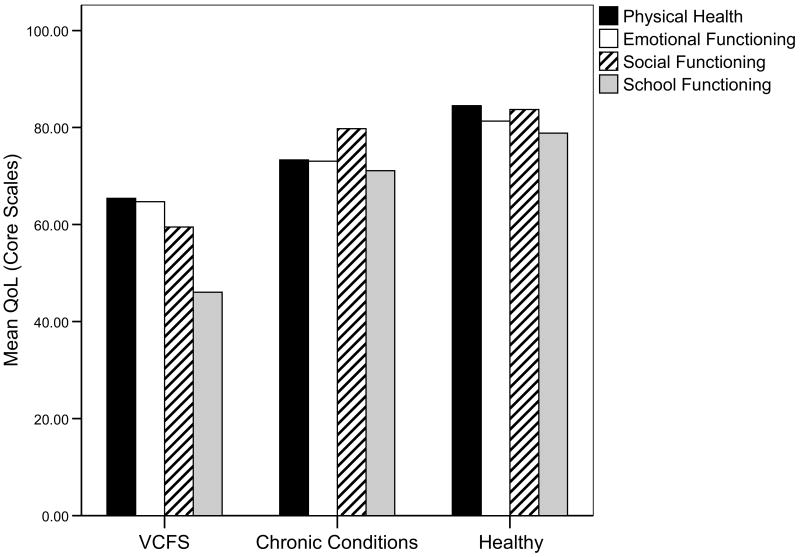

Compared with a sample of healthy children, children with VCFS had significantly lower scores on all four domains of the PedsQL Core Scales and all three domains of the Fatigue Scales. Compared with a sample of children with chronic conditions, the children in this sample scored significantly lower in emotional, social, and school functioning, but not in physical health (Table 4, Figure 1).

Table 4. Comparison of Quality of Life and Fatigue Scores among Children with VCFS, Children with Chronic Conditions and Healthy Children.

| Measure | VCFS Sample | Chronic Conditions Samplec | Healthy Sampled | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Core Scalesa | |||||||||

| Physical Health | 45 | 66.61 | 23.61 | 653 | 73.28 | 27.02 | 9413 | 84.48*** | 19.51 |

| Emotional Functioning | 45 | 62.93 | 20.25 | 661 | 73.05** | 23.27 | 9410 | 81.31*** | 16.50 |

| Social Functioning | 43 | 65.07 | 19.96 | 657 | 79.77** | 29.91 | 9406 | 83.70*** | 19.43 |

| School Functioning | 34 | 44.55 | 17.57 | 601 | 71.08*** | 23.99 | 7989 | 78.83*** | 19.59 |

| Fatigue Scalesb | Healthy Samplee | ||||||||

| General Fatigue | 44 | 64.92 | 18.37 | N/A | 102 | 89.30*** | 13.33 | ||

| Sleep/rest Fatigue | 44 | 77.75 | 16.69 | 102 | 88.86*** | 14.72 | |||

| Cognitive Fatigue | 42 | 44.23 | 24.48 | 102 | 90.72*** | 15.15 |

Figure 1.

Mean quality of life scores for PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales among children with VCFS, children with chronic conditions, and healthy children.

Note: VCFS: velocardiofacial syndrome. All scales have a range of 0-100. Higher values equal better QoL.

Character strengths

Respondents circled between one and sixteen of the descriptions of character strengths (M = 7.53 strengths, SD = 3.53). Of the 18 character strengths listed in the survey, the five most frequently endorsed descriptors were humor (endorsed by 80% of parents), caring (78%), kindness (76%), persistence (62%), and enthusiasm (58%). Parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to endorse enthusiasm as a character strength for their child, while parents of male children were more likely to endorse curiosity as a strength.

Discussion

This study adds to the body of knowledge on children with VCFS as well as the general knowledge on QoL of children with chronic health conditions. Research on the molecular genetics, physical and psychological manifestations, and the cognitive and behavioral challenges faced by children with VCFS continues to flourish. This study contributes new information describing QoL among children with VCFS. The results of this study document the significance of the impact of VCFS across a number of dimensions, particularly in the social, psychological, and educational domains. The results also underscore the significance of cognitive fatigue among the children in this sample.

The finding that boys' scores on school functioning and cognitive fatigue were significantly lower than girls' scores is consistent with recent literature that suggests a differential gender effect in this population. Antshel and others (2005), for example, found that boys with VCFS were more cognitively affected than girls, as has been the case in research on children with developmental disorders in general. The most striking finding in this sample was the extremely low scores for boys on the items pertaining to paying attention, remembering, and thinking quickly. Overall, boys' cognitive fatigue scores in this study were more than three standard deviations below scores in this domain for healthy children. There is a tendency for more males with diagnoses such as attention deficit disorder (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau, 2008). Sex differences in neurodevelopmental disorders may be explained by environmental risk factors, biological processes or differences in gene expression, or differential interactions of environmental and biological influences (Zahn-Waxler, Shirtcliff, & Marceau). The results of this study highlight the effect of these gender differences on QoL among children with VCFS; future studies of children with VCFS will need to further explore these possibilities and the resulting implications for management.

Compared to scores of healthy children in previously published studies, children with VCFS in this sample had significantly lower scores on all domains of QoL and fatigue. These findings confirm the range of implications of this syndrome on affected children, who experience physical, emotional, and social challenges associated with the syndrome. These findings are also consistent with previous studies demonstrating the impact of chronic conditions in general on a child's QoL. Compared to children with chronic conditions, the children with VCFS in this study had significantly lower scores on across all domains except physical health. Because many of the non-cardiac effects of the syndrome are related to cognitive functioning, physical appearance, and speech, physical functioning for children with VCFS may be generally less affected than cognitive functioning, particularly among children whose cardiac status is near normal following repair in infancy. It should be noted, however, that physical health in this study was measured in terms of the child's ability to perform specific activities such as running, lifting, and bathing. The findings of this study confirm the significance of the syndrome's effect in the emotional, social, and school functional domains. The findings suggest that these children have poorer QoL than their peers with single diagnosis chronic conditions which have been studied previously, such as diabetes, asthma, cardiac anomalies, and cancer. Perhaps the complexity of multiple affected systems has a compounding effect on QoL.

The profile of strengths in this sample is similar to findings of healthy children (Park & Peterson, 2006). Strengths of children with VCFS have not received much attention in research. Several of the parents in this study commented in the open-ended response section of the survey that their children are resilient. This is an important characteristic to recognize, as it highlights the strengths that come from surviving adversity. Resilience “involves struggling well, effectively working through and learning from adversity, and integrating the experience into the fabric of individual and shared lives” (Rolland & Walsh, 2006, p. 527). The resilience of children and families who have “struggled well” may be an important asset upon which to draw when designing interventions to help them navigate the challenges of this syndrome.

Limitations of the Study

One of the limitations of this study is the small sample size and the wide range of ages included. Focusing on a particular age group requires a sample large enough for examination of subsets of a sample, and this will be important as research with children with VCFS continues. The specific concerns for children with VCFS and their parents typically vary over time as the child moves through developmental stages and as the condition manifests differently at different stages. At birth, for example, the primary concerns are likely to be related to cardiac status, hypocalcemia, cleft palate, and feeding. Over the next few years of a child's life, developmental delays may be the focus, with cognitive and psychiatric concerns at the forefront as the child moves through adolescence and into adulthood (Kobrynski & Sullivan, 2007). Future studies of children with VCFS should explore how QoL varies by domain as the child ages, and whether functional status at one point in time may be predictive of later function.

Another limitation of this study is that the parents who agreed to participate may be unique in terms of their perception of their child's QoL or functional status. In addition, the parents in this sample were disproportionately White, more highly educated, and represent middle- to upper –middle income households. The assessment of strengths was based on a list generated from the Values in Action Classification; however, this study did not employ a full measure of character strengths due to time constraints and the need to minimize subject burden. We also did not analyze data based on whether the genetic mutation causing VCFS was de novo or familial, and this distinction may be related to differences in IQ (Swillen et al., 1997). Whether a parent respondent has the deletion may have also affected responses.

There is no gold standard for the measurement of QoL, and while the measures used in this study have demonstrated reliability and validity in a number of large samples, there is still a limitation to the measurement of a variable such as QoL. Further, a child's QoL would ideally be ascertained by asking the child directly as opposed to (or in addition to) using parental proxy. In circumstances where the child is too young or cognitively impaired, however, parent proxy report may be needed (Wallander & Varni, 2008). In general, parents have been found to be reliable reporters of their child's QoL (Stade, Stevens, Ungar, Beyene, & Koren, 2006). The nature of this study design precluded the use of child report measures participants, but future studies will incorporate child report in addition to parent report when this is feasible.

Implications for Research and Practice

Quality of life represents a way to describe the results of treatment efforts. Individuals with VCFS typically have multiple physical anomalies, psychological and social difficulties that may impact their quality of life. The goal of interdisciplinary treatment for individuals with chronic conditions such as VCFS is ultimately to improve their quality of life. In order to provide the best possible treatment for individuals with VCFS, professionals who work with this population must have a keen understanding of the individual's quality of life throughout the treatment process. There are multiple factors that guide treatment decision-making; however, quality of life should be at the center. Varni et al. (2002) demonstrated that when a provider used scores on the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales as part of the clinical decision making process, subsequent scores improved over time, suggesting that understanding a patient's current perceived QoL may help tailor interventions.

The child's treatment plan should recognize and reinforce the child and family's strengths as well as the negative impact of VCFS on the child's quality of life. The interdisciplinary team of professionals working with the child and his or her family can facilitate successful management of the condition by identifying what will positively impact the child's QoL, and how the child and family's assets can help move them toward an improved QoL overall. Considering the improved rates of survival for children with VCFS, patient education addressing the dimensions of quality of life along with self-care, transition to adult care and healthy coping skills could potentially last a lifetime. It is important to recognize that individual differences among children with VCFS are important. The challenges and strengths of any particular child must be considered in the context of the syndrome as well as the context of that child's unique personal, family, and environmental context. It would be naive to assume that any two children with this syndrome share the same experiences. Still, it is important to identify and understand the similarities among individuals with VCFS to the extent that tailored interventions and treatment guidelines may be developed.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Andrea Christy for her assistance in data collection for this study, and Adriane Baylis for her review of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding Acknowledgment: This study was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant #P20 NR008992; Center for Health Trajectory Research), and by the J. T. Bennett Velocardiofacial Fund.

Contributor Information

Wendy S. Looman, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota.

Anna K. Thurmes, Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Clinics, University of Minnesota.

Susan K. O'Conner-Von, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota.

References

- Antshel KM, AbdulSabur N, Roizen N, Fremont W, Kates WR. Sex differences in cognitive functioning in velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28(3):849–869. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2803_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Fremont W, Roizen NJ, Shprintzen R, Higgins AM, Dhamoon A, et al. ADHD, major depressive disorder, and simple phobias are prevalent psychiatric conditions in youth with velocardiofacial syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):596–603. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205703.25453.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Swillen A. The cognitive spectrum in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. In: Murphy K, Scambler P, editors. Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: A Model for Understanding Microdeletion Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cho SC, Hwang JW, Lyoo IK, Yoo HJ, Kin BN, Kim JW. Patterns of temperament and character in a clinical sample of Korean children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;62(2):160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SA, Eiser C. The measurement of health-related quality of life (QOL) in paediatric clinical trials: A systematic review. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Cloninger CR, Clarke AR, Hashemi B, Przybeck T. Application of the seven-factor model of personality to early childhood. Psychiatry Research. 2002;109(3):229–243. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiano PC, Tyler MC, Romitti PA, Momany ET, Jones MP, Canady JW, et al. Health-related quality of life among preadolescent children with oral clefts: The mother's perspective. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):e283–290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J, Genova HM, Hillary FG, Wylie G. Neural correlates of cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis using functional MRI. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2008;270(1-2):28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt B, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Vogels A, Gewillig M, Swillen A. Intellectual abilities in a large sample of children with Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: An update. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51(Pt 9):666–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll DA, Spinner NB, Budarf ML, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Goldberg RB, et al. Deletions and microdeletions of 22q11.2 in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1992;44(2):261–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiser C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2001;84:205–211. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Grant MM. Quality of life and symptoms. In: King C, Hinds P, editors. Quality of Life from Nursing and Patient Perspectives. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2003. pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gielissen MF, Knoop H, Servaes P, Kalkman JS, Huibers MJ, Verhagen S, et al. Differences in the experience of fatigue in patients and healthy controls: Patients' descriptions. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson PG, Henry RL, Vimpani GV, Halliday J. Asthma knowledge, attitudes, and quality of life in adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1995;73(4):321–326. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin D, Boggs S, Graham-Pole J. Development and validation of the Pediatric Oncology Quality of Life Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Havermans T, Vreys M, Proesmans M, De Boeck C. Assessment of agreement between parents and children on health-related quality of life in children with cystic fibrosis. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2006;32(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene DL, Higgins MJ, Ventureyra EC. Outcome and life prospects after surgical management of medically intractable epilepsy in patients under 18 years of age. Childs Nervous System. 1997;13(10):530–535. doi: 10.1007/s003810050132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE. Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: The chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Lancet. 2007;370:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer AW, Lee L, Stutz LS, Maroney A, Brandt JW. The prevalence of apraxia characteristics in patients with velocardiofacial syndrome as compared with other cleft populations. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2007;44(2):175–181. doi: 10.1597/05-170.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbers CA, Newman DA, Varni JW. Factorial invariance of child self-report across healthy and chronic health condition groups: A confirmatory factor analysis utilizing the PedsQLTM 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(6):630–639. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker D, Jokovic A, Tompson B. Health-related quality of life of children aged 11 to 14 years with orofacial conditions. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2005;42(3):260–266. doi: 10.1597/03-077.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza LS, Swensen AR, Flood EM, Secnik K, Leidy NK. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children: A review of conceptual, methodological, and regulatory issues. Value in Health. 2004;7(1):79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.71273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald-McGinn DM, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH. Gene Reviews. University of Washington; Seattle: 2005. GeneReviews: 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome [Electronic Version] Retrieved January 13, 2009 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=gr_22q11deletion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, Nelson MB, Parow AM. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;49(3):298–305. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson MD. Resiliency and success in adults with Moebius syndrome. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2001;38(3):231–235. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0231_rasiaw_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi AC, Quittner AL. Validation of a disease-specific measure of health-related quality of life for children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28(7):535–545. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KC. The behavioural phenotype in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2004;48(Pt 6):524–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Scambler P. Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: A Model for Understanding Microdeletion Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. 2007 Retrieved January 13, 2009 from http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition=22q112deletionsyndrome.

- Newacheck PW, Kim SE, Blumberg SJ, Rising JP. Who is at risk for special health care needs: Findings from the National Survey of Children's Health. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):347–359. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Peterson C. The Values in Action Inventory of Character Strengths for Youth. In: Moore KA, Lippman LH, editors. What do Children Need to Flourish? Conceptualizing and Measuring Indicators of Positive Development. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Peterson C. Character strengths and happiness among children: Content analysis of parental descriptors. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7:323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn N, Neyt X, Henderickx D, Soetens E. Psychophysiological investigation of vigilance decrement: Boredom or cognitive fatigue? Physiology & Behavior. 2008;93(1-2):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittner A, Davis M, Modi A. Health-related quality of life in pediatric populations. In: Roberts M, editor. Handbook of Pediatric Psychology. New York: The Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 696–709. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland JS, Walsh F. Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2006;18(5):527–538. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000245354.83454.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler PJ, Kelly D, Lindsay E, Williamson R, Goldberg R, Shprintzen R, et al. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome associated with chromosome 22 deletions encompassing the DiGeorge locus. Lancet. 1992;339:1138–1139. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90734-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, D'Antonio LL, Kalbfleisch JH. Early speech and language development in children with velocardiofacial syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1999;88(6):714–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwid SR, Tyler CM, Scheid EA, Weinstein A, Goodman AD, McDermott MP. Cognitive fatigue during a test requiring sustained attention: A pilot study. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9(5):503–508. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms946oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Search Institute. Mission, Vision, and Value. 2006 www.search-institute.org.

- Seid M, Varni JW, Segall D, Kurtin PS. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of pediatric healthcare costs: A two-year prospective cohort analysis. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solot CB, Knightly C, Handler SD, Gerdes M, McDonald-McGinn DM, Moss E, et al. Communication disorders in the 22Q11.2 microdeletion syndrome. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2000;33(3):187–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(00)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stade BC, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, Beyene J, Koren G. Health-related quality of life of Canadian children and youth prenatally exposed to alcohol. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:81. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K. Immunodeficiency in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. In: Murphy K, Scambler P, editors. Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome: A Model for Understanding Microdeletion Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Swillen A, Devriendt K, Legius E, Eyskens B, Dumoulin M, Gewillig M, et al. Intelligence and psychosocial adjustment in velocardiofacial syndrome: A study of 37 children and adolescents with VCFS. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1997;34(6):453–458. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.6.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolski TD, Edwards TC, Patrick DL. Quality of life: How do adolescents with facial differences compare with other adolescents? Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2005;42(1):25–32. doi: 10.1597/03-097.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand A, Payne J. Theories and conceptual models to guide quality of life related research. In: King C, Hinds P, editors. Quality of Life from Nursing and Patient Perspectives. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2003. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aken K, De Smedt B, Van Roie A, Gewillig M, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, et al. Motor development in school-aged children with 22q11 deletion (velocardiofacial/DiGeorge syndrome) Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49(3):210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94(7):2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2003;3(6):329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Szer IS. The PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in pediatric rheumatology: Reliability and validity. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31(12):2494–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Katz ER, Seid M, Quiggins DJ, Friedman-Bender A, Castro CM. The Pediatric Cancer Quality of Life Inventory (PCQL). I. Instrument development, descriptive statistics, and cross-informant variance. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21(2):179–204. doi: 10.1023/a:1018779908502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: A comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Medical Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Szatmari P, Sparrow SS. Sex differences in pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1993;23(4):579–591. doi: 10.1007/BF01046103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker WT, Temple IK, Gnanapragasam JP, Goddard JR, Brown EM. Quality of life after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Cardiology in the Young. 2002;12(6):549–553. doi: 10.1017/s1047951102000999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1998;39(1):29–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildrick D, Parker-Fisher S, Morales A. Quality of life in children with well-controlled epilepsy. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 1996;28(3):192–198. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:275–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]