Actin dynamics and endocytosis in yeast and mammals (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Oct 1.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010 Jul 14;21(5):604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.06.006

Abstract

Tight regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is critical for many cell functions, including various forms of cellular uptake. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is one of the main methods of uptake in many cell types. An intact and properly regulated actin cytoskeleton is required for CME in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast CME requires the proper regulation of actin polymerization, filament cross-linking, and filament disassembly. Recent studies also point to a role for F-BAR and BAR domain containing proteins in linking the processes of generating and sensing plasma membrane curvature with those regulating the actin cytoskeleton. Many of these same proteins are conserved in mammalian CME. However, until recently the requirement for actin in mammalian CME was less clear. Several recent studies in mammalian cells provide new support for an actin requirement in the invagination and late stages of CME. This review focuses on the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton during CME in yeast and the emerging evidence for a role for actin during mammalian CME.

Introduction

The actin cytoskeleton is utilized in a variety of cellular processes including uptake of nutrients, down-regulation of signaling, motility, and cytokinesis. It is tightly regulated by accessory proteins that promote nucleation and subsequent growth of new actin filaments, the stabilization of an actin network, and the disassembly and turnover of actin filaments, which generates a new G-actin pool ready for another round of polymerization. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is important for endocytosis, and this review will focus on the contributions of the actin cytoskeleton to clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME).

The role of the actin cytoskeleton in endocytosis in budding yeast

Endocytosis and actin assembly in yeast have been linked for some time. Mutants in actin related proteins have been isolated in screens for endocytic mutants, mutations in actin binding protein genes cause endocytic defects, and endocytic and actin assembly proteins colocalize. The definitive connection between these two systems came with the advent of sophisticated live cell imaging in yeast, which demonstrated coordinated assembly and disassembly of endocytic and actin-associated proteins at actin patches [1]. In addition, actin patch components were shown to colocalize with FM4-64 (a lipid dye) and fluorescently labeled alpha-factor (a ligand for a membrane receptor) [2, 3].

A stereotypical series of events takes place at sites of endocytosis. First, endocytic proteins and adaptors, including clathrin, Sla1, Sla2 and End3 appear at the actin patch, followed by regulators of the Arp2/3 complex, a nucleator for actin polymerization. These proteins remain relatively stationary near the cell cortex, presumably attached firmly to the plasma membrane. Near the end of this phase, the first signs of actin assembly appear, as actin-binding proteins, including Arp2/3, Abp1, fimbrin/Sac6, CP and others, appear. Next the majority of endocytic and actin binding proteins move a short distance away from the cell cortex, likely representing the invagination of the membrane to form an endocytic tubule. The fission of the vesicle from the tubule presumably takes place at the end of this phase. The endocytic proteins then leave, but the actin-binding proteins continue to move into the cytoplasm with the vesicle (Reviewed in [4–7]. Current research is focused on understanding the molecular details of how actin assembly at these sites is properly regulated; how actin assembly at these sites is coordinated with the rest of the endocytic machinery; and how the force generated by this actin network is used to drive invagination, scission and subsequent motility of the endocytic vesicle.

Regulation of actin assembly

Actin assembly is required to drive the inward movement of actin patches off the cortex [1, 8]. The actin at these sites is composed of a network of branched actin filaments [9] and the dendritic nucleation model for Arp2/3-based actin assembly may be a good model for how actin assembles at these sites. The major proteins involved in the dendritic nucleation model are all localized to these sites of endocytosis, including Arp2/3, capping protein (CP), and cofilin, and these proteins are all required for normal endocytosis [8, 10, 11]. The Arp2/3 complex appears to be the primary nucleator of actin at patches, and conditional loss of Arp2/3 function leads to significant defects in patch behavior [10]. The acute loss of formins, another major class of actin nucleator in yeast, does not result in a loss of actin patch assembly or proper endocytic motility [8].

The nucleation of actin filaments is a critical step in the formation of proper actin networks. In mammalian systems, the nucleation activity of Arp2/3 requires binding to a Nucleation Promoting Factor (NPF) [12]. In contrast, the yeast Arp2/3 complex is relatively active without a NPF [13], so simply localizing Arp2/3 properly may be sufficient to regulate its activity. In yeast there are five NPFs that localize to the actin patch [14]. Interestingly, while disruption of the Arp2/3 binding regions of these proteins can disrupt aspects of endocytosis, in all mutants examined to date, actin still accumulates at sites of endocytosis [15, 16] (Galletta, BJ and Cooper, JA, unpublished observations). This may suggest that the major role of the NPFs may not be to induce Arp2/3 to nucleate filaments. A more detailed study of the precise effects of these NPF mutants will be required to confirm this hypothesis and understand the exact role of Arp2/3 binding by these NPFs. In addition, some mutations of Arp2/3 itself, which dramatically reduce the in vitro nucleation activity of Arp2/3, do not have a major effect on the accumulation of actin in vivo [17]. Thus, Arp2/3 may be important for more than simply nucleating new branched filaments during endocytosis in yeast and this raises the question of what is nucleating the filaments in actin patches [17].

In the cell, actin patch filament networks are very dynamic, so that regulation of their disassembly is likely to be important. Three proteins, cofilin, Aip1 and coronin, which in vitro studies suggest work together to disassemble actin, are present in the patch [18–24] Consistent with a role in actin network turnover, all three of these proteins arrive to the patch after actin assembly has begun [25], and loss of function mutants in these proteins slows the turnover of actin in cells [11, 19, 26]. Severe loss of function mutations in cofilin cause an extended lifetime at the cell cortex by patches, but they do not affect the initial movement of invagination. After leaving the cell cortex, actin patches in cofilin mutants move further into the cytoplasm, consistent with a defect in disassembling actin networks [25, 27].

Loss of coronin, like cofilin mutants, results in an increased time spent at the membrane prior to initiation of movement and an increase in the distance moved after scission, although to a much lesser degree than described for cofilin mutants [15, 25]. In vitro, the activity of coronin can change depending on the nucleotide state of the actin filament. On ATP actin filaments, coronin can protect the actin from cofilin, but on ADP actin, coronin can synergize with cofilin to sever actin filaments and coronin may have some severing activity of its own [19]. Loss of Aip1 also results in an increased time spent at the membrane prior to patch movement, but the movement of patches appears normal [25]. Aip1 may be acting to help generate actin monomers from short actin oligomers generated by cofilin. In its absence, cells accumulate short actin oligomers that may anneal, minimizing the impact of its loss on actin dynamics [28]. It should be noted that the actin patch motility phenotypes of cells where coronin and/or Aip1 have been deleted are much less severe than what is seen in cofilin mutants [25]. This suggests that if coronin and aip1 are cooperating with cofilin, they make relatively minor contributions to normal cofilin function and actin patch movement in vivo.

Linkage between actin and membrane bending proteins

The interplay between the actin network and the proteins that bind to, and can bend, the plasma membrane, is emerging as an important area of study. BAR and F-BAR proteins may serve to bend the membrane, as well as to sense membrane curvature [29]. In yeast there are several BAR and F-BAR domain proteins in the actin patch, including Syp1, Bzz1, Rvs161, and Rvs167.

Syp1 is recruited very early in the lifetime of the patch, with similar timing as clathrin. Syp1 is almost completely gone from the patch when actin polymerization begins [30–32]. Syp1 can bind to and tubulate liposomes in vitro. [32]. Most interestingly, Syp1 can negatively regulate WASp/Las17-Arp2/3 mediated actin polymerization in vitro. Boettner and colleagues have suggested an intriguing model where Syp1’s BAR domain assists in generating the initial curvature of the plasma membrane, while simultaneously inhibiting actin nucleation. As the curvature of the membrane changes as endocytosis proceeds, Syp1 is released allowing actin nucleation to proceed [31].

Another F-BAR domain containing protein, Bzz1, is recruited to the patch after Syp1, just prior to the initiation of actin polymerization [16]. Bzz1 has the opposite effect of stimulating WASp-based actin polymerization. The SH3 domains of Bzz1 interact directly with WASp/Las17, and they are sufficient to induce actin polymerization on beads when incubated with yeast cell extracts. This actin polymerization depends on Arp2/3, Las17, Vrp1, and type-I myosins [33, 34]. In in vitro polymerization assays Bzz1 can relieve the inhibition of Las17 activity by Sla1 [16]. Toca-1 and FBP17, the likely mammalian counterparts to Bzz1, can recruit the N-WASp/WIP complex to the membrane and activate WASp/WIP to initiate actin polymerization in a membrane curvature-dependent manner [35]. An appealing model is that Bzz1 senses the curvature induced by earlier F-BAR proteins, like Syp1, and starts polymerization on the already curved membrane.

The BAR domain containing amphiphysin proteins, Rvs161 and Rvs167, arrive after actin polymerization has begun, at approximately the time when membrane fission is thought to occur. Consistent with a defect in membrane scission, Rvs167 localizes to the sides of endocytic invaginations by immuno-EM and cells lacking Rvs161 or Rvs167 show frequent retractions of endocytic proteins following their inward movement [36, 37]. Rvs167 can bind to WASp/Las17, so it too may regulate actin network assembly [38].

The role of the actin cytoskeleton in mammalian endocytosis

As described above, there is an absolute requirement for the actin cytoskeleton in S. cerevisiae clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). There is also evidence for a role for actin in CME in Drosophila [39]. In mammalian systems, the actin cytoskeleton is known to participate in various modes of cellular uptake from the environment, including phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, and caveolin-mediated endocytosis. However, the requirement for actin in mammalian CME is less clear.

In mammalian systems, there is strong biochemical evidence for interactions between many of the endocytic adaptors and the actin cytoskeleton, including several conserved from S. cerevisiae. Many proteins that link the endocytic machinery and the actin cytoskeleton potentially regulate actin assembly at endocytic sites. For example, Hip1R, the mammalian orthologue of yeast Sla2, binds clathrin, F-actin and cortactin to negatively regulate actin assembly [40]. Intersectin binds epsin (similar to Ent1 and Ent2 in yeast) and N-WASp, an activator of actin assembly [41]. Both cortactin and mAbp1 (yeast Abp1) can activate actin assembly and bind to F-actin and to dynamin, the mammalian GTPase involved in vesicle fission from the plasma membrane [42–44]. Other proteins link dynamin to N-WASp, such as SNX9/SNX18, Tuba and the F-BAR-domain proteins syndapin, Toca-1/CIP4, and formin-binding protein 17 (FBP17) [35, 45–52]. Additionally, the BAR domain protein PICK1, binds to Arp2/3 complex and inhibits actin polymerization in vitro [53].

Certain cell biology experiments support a role for the actin cytoskeleton in mammalian CME. For example, actin is recruited to clathrin-coated pits prior to movement of the vesicle away from the plasma membrane. Actin also contributes to the shape of the endocytic pit and the lateral movement of clathrin-coated pits within the membrane [54, 55]. However, experiments that treat cells with reagents to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton have resulted in conflicting results, depending on the cell types [55–57]. Several recent papers have attempted to reconcile these inconsistencies and to determine the role of the actin cytoskeleton in mammalian CME.

Kirchhausen and co-workers recently performed a careful analysis of CME events and reported two classes of CME structures, termed coated pits and coated plaques [57]. These two classes of clathrin-coated structures had distinct kinetic properties, with short-lived coated pits characterizing the typical clathrin endocytic vesicle, and longer-lived coated plaques occurring at the adherent surface of certain cell types. Dynamic actin and actin-binding proteins, Hip1R and cortactin, were necessary for the formation and invagination of the coated plaque population, but not for the coated pit population. The authors argue that the existence of these two populations of clathrin-coated structures accounts for the discrepancies reported for a critical role for the actin cytoskeleton and actin-binding proteins in CME.

Locally regulated cortical tension on the plasma membrane of mammalian cells may differentially affect clathrin-coated pit kinetics [58]. Using BSC1 cells, which do not form the coated plaques described above but only coated pits, three subpopulations of clathrin-coated pits (CCPs) were described: early and late abortive (short-lived), and productive (longer-lived) [57, 59]. Within the productive subpopulation, there was still heterogeneity in the kinetics of internalization, suggesting additional factors regulating CME.

A recent paper by De Camilli and co-workers demonstrated the concerted actions of BAR-domain proteins and the actin cytoskeleton to invaginate and tubulate membranes associated with clathrin pits prior to scission [60]. Cells derived from dynamin 1 and 2 double conditional knockout mice resulted in significant impairment of CME and the growth of long tubulated clathrin-coated pits to which BAR-domain proteins, F-actin and actin binding proteins colocalized. The actin cytoskeleton was required to maintain the tubules. The authors suggest a model of CME in which clathrin recruits additional endocytic components, including BAR-domain proteins and actin binding proteins. Subsequent coordinating actions of BAR-domain proteins and actin promote the invagination and tubulation of clathrin-coated pits until dynamin is recruited resulting in fission of the vesicle from the membrane.

The results from De Camilli and co-workers are intriguing because they demonstrate parallels between yeast and mammalian cell CME mechanisms, which some investigators have considered to be distinct. These parallels would indicate that the actin cytoskeleton plays a conserved critical role in the invagination of clathrin-coated pits, and perhaps at later stages, such as fission and movement of vesicles away from the membrane subsequent to fission.

Danuser and co-workers measured lifetimes of clathrin-coated pits of cells attached to patterned substrates [58]. The lifetimes of CCPs within regions of the cell that were attached to fibronectin were significantly longer than the lifetimes of CCPs measured outside of the region of attachment. Using reagents to reduce cortical tension by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton resulted in a reduction of the lifetimes of CCPs in the attached regions so that there was no measurable difference in the lifetimes of the CCPs within the two regions. Therefore, localized changes in cortical tension via actin cytoskeletal rearrangements may contribute to CME and may account for the heterogeneity of the kinetics reported previously.

Recent studies suggest that because yeast have a cell wall and increased turgor pressure compared to mammalian cells, yeast CME may require a stabilized actin network to provide sufficient force for membrane invagination [61]. This is supported by additional evidence that disruption of the cortical actin cytoskeleton in mammalian cells reduces membrane tension and low expression of BAR-domain proteins can artificially induce long membrane tubules when the actin cytoskeleton is compromised [62, 63]. Therefore, regulation of the actin cytoskeleton may modulate membrane tension to facilitate invagination of clathrin-coated pits in both yeast and mammalian cells.

Conclusions

Models for how actin assembly drives invagination

While it is clear that a dynamic actin cytoskeleton is essential for endocytosis in yeast and evidence is mounting for a role for actin in mammalian systems, precisely how this actin network is used to help provide the force required for the invagination, scission and vesicle motility during endocytosis is unclear. In one model, the actin filaments are primarily nucleated from a ring of NPFs around the base of the endocytic invagination. The growing barbed ends of the filaments remain pointed towards the plasma membrane, resulting in a flow of actin filaments away from the cortex. These filaments are attached to the membrane and the flow of this network away from the plasma membrane helps extrude the invagination into the cytoplasm (Figure 1A). While the flow of actin away from the cortex is supported by observations of _sla2&_Delta; cells, these cells have very severe defects in endocytosis and the large, flowing actin comet tails seen in these cells may represent a structure found very early during endocytosis or even a structure specific to cells blocked for endocytosis in this way. Furthermore, this model requires that new actin subunits, Arp2/3 and actin binding proteins like capping protein would be incorporated at the membrane as invagination takes place. However, there is no evidence for any of these proteins remaining at the membrane or occupying the region between the endocytic particle and the membrane. All of the actin associated proteins move into the cytoplasm and away from the membrane.

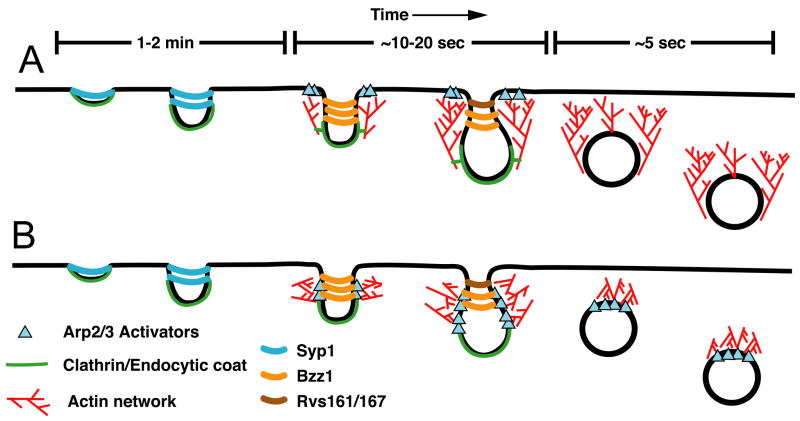

Figure 1.

Major models for actin assembly during endocytosis derived from the results of numerous works described and referenced herein. In both A and B the initial curvature of the membrane is generated by clathrin and additional endocytic proteins, such as F-BAR containing Syp1. Syp1 can inhibit WASp/Las17-Arp2/3 mediated actin assembly and may serve to keep actin polymerization inhibited during early steps of CME. As invagination proceeds, the changing membrane curvature may be sensed by other BAR domain containing proteins, for example Bzz1, which is recruited along with other endocytic proteins and regulators of Arp2/3. In model A, a ring of NPFs activate Arp2/3 which nucleates an actin network that flows away from the plasma membrane. Proteins of the endocytic coat link the membrane to this flowing network and this provides the force to invaginate further into the cell. The amphiphysin proteins, Rvs161 and Rvs167, drive membrane scission. In model B, actin is nucleated along the sides of the membrane tubule, perhaps in response to the loss of Syp1, and the recruitment of Bzz1, which can promote actin nucleation. The growing barbed ends of the actin push on the membrane tubule, squeezing it, driving elongation and assisting the amphiphysin proteins during membrane scission. In this model, the actin network is in a position to drive movement after the vesicle has been freed from the membrane. The best models for how actin polymerization is utilized during clathrin-mediated endocytosis in mammals are similar to the model presented in B [64, 65]

An alternative model is similar to one proposed by Merrifield and colleagues for animal cells and another one recently elaborated by Suetsugu [64, 65]. In this model (Figure 1B) actin is polymerized around the endocytic coat, which has already generated some degree of curvature in the membrane. The presence of curvature prior to actin polymerization is supported by EM data [37]. Furthermore, as documented above, F-BAR domain-containing proteins may help direct actin polymerization to invaginations. The force from these filaments can squeeze the invagination and help push the endocytic membrane into the cytoplasm. In this model, the actin machinery remains directly adjacent to the endocytic machinery and no connection to the plasma membrane is required. The actin filaments are in position to help during scission and to drive motility after membrane scission, which requires a properly functioning dendritic actin network [8, 15, 25, 66].

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health GM 38542 to J.A.C. and F32 GM 083538 to O.L.M.) for work described and in preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Kaksonen M, Sun Y, Drubin DG. A pathway for association of receptors, adaptors, and actin during endocytic internalization. Cell. 2003;115:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toshima JY, Toshima J, Kaksonen M, Martin AC, King DS, Drubin DG. Spatial dynamics of receptor-mediated endocytic trafficking in budding yeast revealed by using fluorescent {alpha}-factor derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5793–5798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601042103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huckaba TM, Gay AC, Pantalena LF, Yang HC, Pon LA. Live cell imaging of the assembly, disassembly, and actin cable-dependent movement of endosomes and actin patches in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galletta BJ, Cooper JA. Actin and endocytosis: mechanisms and phylogeny. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. Harnessing actin dynamics for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson AS, Smythe E, Ayscough KR. Functions of actin in endocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2049–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girao H, Geli MI, Idrissi FZ. Actin in the endocytic pathway: from yeast to mammals. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2112–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim K, Galletta BJ, Schmidt KO, Chang FS, Blumer KJ, Cooper JA. Actin-based motility during endocytosis in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1354–1363. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young ME, Cooper JA, Bridgman PC. Yeast actin patches are networks of branched actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:629–635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter D, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Li R. The complex containing actin-related proteins Arp2 and Arp3 is required for the motility and integrity of yeast actin patches. Curr Biol. 1997;7:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lappalainen P, Drubin DG. Cofilin promotes rapid actin filament turnover in vivo. Nature. 1997;388:78–82. doi: 10.1038/40418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campellone KG, Welch MD. A nucleator arms race: cellular control of actin assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:237–251. doi: 10.1038/nrm2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen KK, Rubenstein PA. Acceleration of yeast actin polymerization by yeast ARP2/3 complex does not require an ARP2/3 activating protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24168–24174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver AM, Young ME, Lee WL, Cooper JA. Integration of signals to the Arp2/3 complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galletta BJ, Chuang DY, Cooper JA. Distinct Roles for Arp2/3 Regulators in Actin Assembly and Endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y, Martin AC, Drubin DG. Endocytic internalization in budding yeast requires coordinated actin nucleation and myosin motor activity. Dev Cell. 2006;11:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin AC, Xu XP, Rouiller I, Kaksonen M, Sun Y, Belmont L, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Welch M, Drubin DG. Effects of Arp2 and Arp3 nucleotide-binding pocket mutations on Arp2/3 complex function. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:315–328. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono S. Mechanism of depolymerization and severing of actin filaments and its significance in cytoskeletal dynamics. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;258:1–82. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)58001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi M, Achard V, Blanchoin L, Goode BL. Coronin switches roles in actin disassembly depending on the nucleotide state of actin. Mol Cell. 2009;34:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brieher WM, Kueh HY, Ballif BA, Mitchison TJ. Rapid actin monomer-insensitive depolymerization of Listeria actin comet tails by cofilin, coronin, and Aip1. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:315–324. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kueh HY, Charras GT, Mitchison TJ, Brieher WM. Actin disassembly by cofilin, coronin, and Aip1 occurs in bursts and is inhibited by barbed-end cappers. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:341–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon AL, Janmey PA, Louie KA, Drubin D. Cofilin is an essential component of the yeast cortical cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120:421–435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodal AA, Tetreault JW, Lappalainen P, Drubin DG, Amberg DC. Aip1p interacts with cofilin to disassemble actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1251–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heil-Chapdelaine RA, Tran NK, Cooper JA. The role of Saccharomyces cerevisiae coronin in the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1281–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Lin MC, Galletta BJ, Sept D, Cooper JA. Overlapping and distinct functions for cofilin, coronin and Aip1 in actin dynamics in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1329–1342. doi: 10.1242/jcs.065698. Using fluorescent protein fusions to actin patch proteins, including an improved cofilin fusion, the authors examine the roles of cofilin, Aip1 and coronin during endocytosis in budding yeast. This work supports a model in which these proteins work together during actin disassembly, but demonstrates that cofilin is far more important than coronin or Aip1 for this process. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada K, Ravi H, Smith EM, Goode BL. Aip1 and cofilin promote rapid turnover of yeast actin patches and cables: a coordinated mechanism for severing and capping filaments. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2855–2868. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okreglak V, Drubin DG. Cofilin recruitment and function during actin-mediated endocytosis dictated by actin nucleotide state. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1251–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okreglak V, Drubin DG. Loss of Aip1 reveals a role in maintaining the actin monomer pool and an in vivo oligomer assembly pathway. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:769–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itoh T, De C, Pietro BAR, F-BAR (EFC) and ENTH/ANTH domains in the regulation of membrane-cytosol interfaces and membrane curvature. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2006;1761:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stimpson HE, Toret CP, Cheng AT, Pauly BS, Drubin DG. Early-arriving Syp1p and Ede1p function in endocytic site placement and formation in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4640–4651. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **31.Boettner DR, D’Agostino JL, Torres OT, Daugherty-Clarke K, Uygur A, Reider A, Wendland B, Lemmon SK, Goode BL. The F-BAR protein Syp1 negatively regulates WASp-Arp2/3 complex activity during endocytic patch formation. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1979–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.062. The F-BAR protein Syp1 is identified as a negative regulator of WASp-Arp2/3 mediated actin assembly providing a possible link between the regulation of membrane curvature and actin assembly. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reider A, Barker SL, Mishra SK, Im YJ, Maldonado-Baez L, Hurley JH, Traub LM, Wendland B. Syp1 is a conserved endocytic adaptor that contains domains involved in cargo selection and membrane tubulation. EMBO J. 2009;28:3103–3116. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soulard A, Lechler T, Spiridonov V, Shevchenko A, Li R, Winsor B. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Bzz1p is implicated with type I myosins in actin patch polarization and is able to recruit actin-polymerizing machinery in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7889–7906. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7889-7906.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soulard A, Friant S, Fitterer C, Orange C, Kaneva G, Mirey G, Winsor B. The WASP/Las17p-interacting protein Bzz1p functions with Myo5p in an early stage of endocytosis. Protoplasma. 2005;226:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s00709-005-0108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takano K, Toyooka K, Suetsugu S. EFC/F-BAR proteins and the N-WASP-WIP complex induce membrane curvature-dependent actin polymerization. EMBO J. 2008;27:2817–2828. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. A modular design for the clathrin- and actin-mediated endocytosis machinery. Cell. 2005;123:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Idrissi FZ, Grotsch H, Fernandez-Golbano IM, Presciatto-Baschong C, Riezman H, Geli MI. Distinct acto/myosin-I structures associate with endocytic profiles at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:1219–1232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708060. This immuno-EM study of several endocytic and actin assembly factors during endocytosis provides important information about the positions of key proteins relative to the endocytic tubule. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colwill K, Field D, Moore L, Friesen J, Andrews B. In vivo analysis of the domains of yeast Rvs167p suggests Rvs167p function is mediated through multiple protein interactions. Genetics. 1999;152:881–893. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kochubey O, Majumdar A, Klingauf J. Imaging clathrin dynamics in Drosophila melanogaster hemocytes reveals a role for actin in vesicle fission. Traffic. 2006;7:1614–1627. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Clainche C, Pauly BS, Zhang CX, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Cunningham K, Drubin DG. A Hip1R-cortactin complex negatively regulates actin assembly associated with endocytosis. EMBO J. 2007;26:1199–1210. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pechstein A, Shupliakov O, Haucke V. Intersectin 1: a versatile actor in the synaptic vesicle cycle. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:181–186. doi: 10.1042/BST0380181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNiven MA, Kim L, Krueger EW, Orth JD, Cao H, Wong TW. Regulated interactions between dynamin and the actin-binding protein cortactin modulate cell shape. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:187–198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessels MM, Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG, Qualmann B. Mammalian Abp1, a signal-responsive F-actin-binding protein, links the actin cytoskeleton to endocytosis via the GTPase dynamin. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:351–366. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinyol R, Haeckel A, Ritter A, Qualmann B, Kessels MM. Regulation of N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex by Abp1 controls neuronal morphology. PLoS One. 2007;2:e400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessels MM, Qualmann B. Syndapin oligomers interconnect the machineries for endocytic vesicle formation and actin polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13285–13299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salazar MA, Kwiatkowski AV, Pellegrini L, Cestra G, Butler MH, Rossman KL, Serna DM, Sondek J, Gertler FB, De Camilli P. Tuba, a novel protein containing bin/amphiphysin/Rvs and Dbl homology domains, links dynamin to regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49031–49043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yarar D, Waterman-Storer CM, Schmid SL. SNX9 couples actin assembly to phosphoinositide signals and is required for membrane remodeling during endocytosis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park J, Kim Y, Lee S, Park JJ, Park ZY, Sun W, Kim H, Chang S. SNX18 shares a redundant role with SNX9 and modulates endocytic trafficking at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1742–1750. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fricke R, Gohl C, Dharmalingam E, Grevelhorster A, Zahedi B, Harden N, Kessels M, Qualmann B, Bogdan S. Drosophila Cip4/Toca-1 integrates membrane trafficking and actin dynamics through WASP and SCAR/WAVE. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho HY, Rohatgi R, Lebensohn AM, Le M, Li J, Gygi SP, Kirschner MW. Toca-1 Mediates Cdc42-Dependent Actin Nucleation by Activating the N-WASP-WIP Complex. Cell. 2004;118:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamioka Y, Fukuhara S, Sawa H, Nagashima K, Masuda M, Matsuda M, Mochizuki N. A novel dynamin-associating molecule, formin-binding protein 17, induces tubular membrane invaginations and participates in endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40091–40099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsujita K, Suetsugu S, Sasaki N, Furutani M, Oikawa T, Takenawa T. Coordination between the actin cytoskeleton and membrane deformation by a novel membrane tubulation domain of PCH proteins is involved in endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rocca DL, Martin S, Jenkins EL, Hanley JG. Inhibition of Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization by PICK1 regulates neuronal morphology and AMPA receptor endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:259–271. doi: 10.1038/ncb1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Merrifield CJ, Perrais D, Zenisek D. Coupling between clathrin-coated-pit invagination, cortactin recruitment, and membrane scission observed in live cells. Cell. 2005;121:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.015. Using both epifluorescence and evanescent field microscopy, invagination and scission during clathrin-mediated endocytosis were monitored. Cortactin, an actin- and dynamin-binding protein, was recruited to sites of CME during the scission stage. Treatment with latrunculin B disrupted clathrin-coated pit dynamics and reduced the number of scission events. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Yarar D, Waterman-Storer CM, Schmid SL. A dynamic actin cytoskeleton functions at multiple stages of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:964–975. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0774. Investigators used biochemical reagents to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton and reported affects on clathrin-coated pit dynamics, including formation, constriction, internalization and lateral mobility within the plasma membrane of pits. These results suggest that the actin cytoskeleton plays an important role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujimoto LM, Roth R, Heuser JE, Schmid SL. Actin assembly plays a variable, but not obligatory role in receptor- mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. Traffic. 2000;1:161–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **57.Saffarian S, Cocucci E, Kirchhausen T. Distinct dynamics of endocytic clathrin-coated pits and coated plaques. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000191. In some adherent cell types, two populations of clathrin-coated structures are observed, including a shorter-lived coated pit and a longer-lived coated plaque population. The dynamics and kinetics of these two populations are distinct, with the coated plaque population requiring an intact actin cytoskeleton for invagination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **58.Liu AP, Loerke D, Schmid SL, Danuser G. Global and local regulation of clathrin-coated pit dynamics detected on patterned substrates. Biophys J. 2009;97:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.003. Reducing cortical tension by disrupting the actin cytoskeleton reduced clathrin-coated pit lifetimes, suggesting that localized changes in cortical tension induced by actin dynamics may contribute to clathrin-mediated endocytosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dinah Loerke MM, Yarar Defne, Jaqaman Khuloud, Jaqaman Hengry, Danuser Gaudenz, Sandra L. Schmid. Cargo and Dynamin Regulate Clathrin-Coated Pit Maturation. PLoS Biology. 2009;7:e1000057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **60.Ferguson SM, Raimondi A, Paradise S, Shen H, Mesaki K, Ferguson A, Destaing O, Ko G, Takasaki J, Cremona O, O’Toole E, De Camilli Coordinated actions of actin and BAR proteins upstream of dynamin at endocytic clathrin-coated pits. Dev Cell. 2009;17:811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.005. Investigators use cells derived from dynamin 1 and 2 conditional double-knock out mice to study the role of the actin cytoskeleton and BAR-domain proteins in the absence of dynamin. In the absence of dynamin, long tubules capped by clathrin grew from the plasma membrane to which components of the actin cytoskeleton and BAR-domain proteins colocalized. An intact actin cytoskeleton was required for the formation of the tubules, suggesting a coordinating role for actin and BAR-domain proteins in the invagination and tubulation of clathrin-pits, which terminates with fission by dynamin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Aghamohammadzadeh S, Ayscough KR. Differential requirements for actin during yeast and mammalian endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1039–1042. doi: 10.1038/ncb1918. The requirement for the actin cytoskeleton is vital in yeast clathrin-mediated endocytosis. By reducing turgor pressure in yeast cells, the requirement for actin was reduced and increasing turgor pressure reduced invagination. This suggests that an intact actin cytoskeletal network is critical in yeast to support invagination against high turgor pressure and may explain the differential requirements for actin in yeast versus mammalian cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wakatsuki T, Schwab B, Thompson NC, Elson EL. Effects of cytochalasin D and latrunculin B on mechanical properties of cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1025–1036. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Itoh T, Erdmann KS, Roux A, Habermann B, Werner H, De Camilli P. Dynamin and the actin cytoskeleton cooperatively regulate plasma membrane invagination by BAR and F-BAR proteins. Dev Cell. 2005;9:791–804. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suetsugu S. The direction of actin polymerization for vesicle fission suggested from membranes tubulated by the EFC/F-BAR domain protein FBP17. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3401–3404. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merrifield CJ. Seeing is believing: imaging actin dynamics at single sites of endocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gheorghe DM, Aghamohammadzadeh S, Smaczynska-de Rooij II, Allwood EG, Winder SJ, Ayscough KR. Interactions between the yeast SM22 homologue Scp1 and actin demonstrate the importance of actin bundling in endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15037–15046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710332200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]