Proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis is mediated by positive feedback amplification of PKCδ proteolytic activation and mitochondrial translocation (original) (raw)

Abstract

Emerging evidence implicates impaired protein degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) in Parkinson's disease; however cellular mechanisms underlying dopaminergic degeneration during proteasomal dysfunction are yet to be characterized. In the present study, we identified that the novel PKC isoform PKCδ plays a central role in mediating apoptotic cell death following UPS dysfunction in dopaminergic neuronal cells. Inhibition of proteasome function by MG-132 in dopaminergic neuronal cell model (N27 cells) rapidly depolarized mitochondria independent of ROS generation to activate the apoptotic cascade involving cytochrome c release, and caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation. PKCδ was a key downstream effector of caspase-3 because the kinase was proteolytically cleaved by caspase-3 following exposure to proteasome inhibitors MG-132 or lactacystin, resulting in a persistent increase in the kinase activity. Notably MG-132 treatment resulted in translocation of proteolytically cleaved PKCδ fragments to mitochondria in a time-dependent fashion, and the PKCδ inhibition effectively blocked the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, indicating that the accumulation of the PKCδ catalytic fragment in the mitochondrial fraction possibly amplifies mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Overexpression of the kinase active catalytic fragment of PKCδ (PKCδ-CF) but not the regulatory fragment (RF), or mitochondria-targeted expression of PKCδ-CF triggers caspase-3 activation and apoptosis. Furthermore, inhibition of PKCδ proteolytic cleavage by a caspase-3 cleavage-resistant mutant (PKCδ-CRM) or suppression of PKCδ expression by siRNA significantly attenuated MG-132-induced caspase-9 and -3 activation and DNA fragmentation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that proteolytically activated PKCδ has a significant feedback regulatory role in amplification of the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cascade during proteasome dysfunction in dopaminergic neuronal cells.

Keywords: Ubiquitin Proteasomal System (UPS), Protein Kinase C delta, Parkinsons disease, Neurodegeneration, Apoptosis, mitochondria

Introduction

Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is one of the major intracellular proteolysis systems responsible for degradation of damaged or misfolded proteins and proteins involved in various cellular processes including apoptosis. Polyubiquitination of target proteins, which is essential for their recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome complex, involves a cascade of ubiquitinating enzymes including ubiquitin activating enzyme, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, and ubiquitin ligase [1].

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder, affecting over 4 million people worldwide, and is becoming more prevalent each year. The disease is characterized by the selective and progressive loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons, with the underlying neuronal death remaining elusive [2]. Lines of evidence for pathogenic roles of dysfunctional UPS in PD include reduced proteasomal activities, selective loss of proteasome subunits in substantia nigra of patients with sporadic PD, and mutation of several genes involved in the UPS degradation pathway in familial PD [2–4]. Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in Lewy bodies, presumably due to failure of the clearance of target proteins by UPS, is indicative of impaired UPS function in PD. Exposure to pharmacological inhibitors of the proteasome replicates some biochemical and pathological characteristics of PD cell culture and animal models. Proteasome inhibition has been previously shown to result in α-synuclein protein aggregation and cell death in various cell models including mesencephalic dopamin-ergic neurons [2]. The Parkinsonian toxin MPTP has been shown to cause UPS dysfunction and protein aggregation in the substantia nigra [5, 6]. Additionally, other neurotoxic pesticides linked to PD such as rotenone and dieldrin cause proteasome inhibition and protein aggregation [2]. Systemically administered proteasome inhibitors produce inconsistent results in producing Parkinsonian-like pathology in rodents [7–12]. Recently, we and others demonstrated that microinjection of proteasome inhibitors into substantia nigra or striatum effectively reproduces a nigrostriatal dopamine degeneration [13–15]. Despite extensive observations of defective UPS degradation in PD pathogenesis, the cellular and molecular mechanisms leading to dopamine neuronal death following proteasomal dysfunction remain to be characterized. In the present study, we report for the first time that proteolytic activation and mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ play a critical role in apoptotic cell death during proteasome dysfunction in dopaminergic neuronal cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment paradigm

The immortalized rat mesencephalic dopaminergic cell line (N27 cells) was grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 units penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C [16, 17]. Cells were treated with different concentrations of MG-132 or lactacystin dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (0.1% DMSO final concentration) for the indicated duration in the experiments. Control groups were treated with 0.1% DMSO.

Mitochondria depolarization assay

The cationic lipophilic fluorescent dye JC-1 accumulates in the matrix of healthy mitochondria through a membrane potential-dependent manner and thus fluoresces red. However, JC-1 cannot accumulate in mitochondria with collapsed membrane potential, and thus exists in cytoplasm at low concentration as a monomer, which fluoresces green. The intensity of red and green fluorescence provides a reliable measurement of mitochondria membrane potential. N27 cells grown in 6-well plates were treated with MG-132 prior to incubation with JC-1 dye (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA) for 20 min at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. Red and green fluorescence were determined for the treated cells performed with a flow cytometer with a setting of ‘double-bandpass’ filter Ex/Em 485/535 nm for green fluorescence and Ex/Em 590/610 nm for red fluorescence, and the ratio between red/green was used as an indicator of mitochondria potential.

ROS assay

Flow cytometric analysis of reactive oxygen species in N27 cells was performed with dihydroethidine, as described previously [18–21]. In cytosol, blue fluorescent dihydroethidium can be dehydrogenated by superoxide (O2∼) to form ethidium bromide, which subsequently produces a bright red fluorescence (620 nm). N27 cells were collected by trypsinization and resuspended in Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS) with 2-mM calcium at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml. The cell suspension then was incubated with 10 μM hydroethidine at 37°C in the dark. Following addition of MG-132, ROS generation in N27 cells was measured at 0, 20, 40 and 60 min in a flow cytometer (Em/Ex 488/585 nm with 42-nm bandpass). Treatment with H2O2 was used as positive control. ROS levels were normalized as percentage of time-matched control. ROS generation was also examined by monitoring fluorescence using microscopic analysis.

Microscopic assays of ROS production were conducted using dihydroethidium or CM-H2DCFDA by following the protocols suggested by the manufacturers. Briefly, 24 hrs after cells were in culture, N27 cells in 96-well plate were then treated with MG-132 (1, 3 or 5 μM) for 1, 3 or 6 hrs. Incubation of the treated cells with 5 μM dihydroethidium or 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA for an additional 15 min was performed, and the cells were then visualized under fluorescence microscopy with Em at 620 nm and 535 nm for dihydroethidium or CM-H2DCFDA, respectively.

Caspase enzymatic activity assay

Caspase activities were assessed as described in our publications [17, 18]. Cells were lysed with 10 μM digitonin in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA). The supernatants (14,000 μ_g_, 5 min) of the lysates were incubated with 50 μM of the fluorogenic substrates Ac-DEVD-AFC, Ac-IETD-AFC and Ac-LEHD-AFC (Biomol International, Plymouth Meeting, PA) for determination of caspase-3, -8 and -9 activities, respectively. Levels of cleaved substrate (active caspase) were monitored performed with a fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA, Ex/Em 400/505 nm). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method and used for normalization of caspase activity.

Subcellular fractionation, preparation of cell lysate and Western blot

Mitochondria isolation was conducted, as described previously [22] with modification. Cells were resuspended in homogenization buffer (pH 7.5, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors), and homogenized with a glass Dounce homogenizer. Unlysed cells, cell debris and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1000 ×g for 10 min The supernatant was further centrifuged at 10,000 x gfor 25 min to obtain supernatant fraction and pellet as cytosolic and mitochondria fractions. For whole cell lysates, cells were homogenized by sonication in homogenization buffer (pH 8.0, 20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail [AEBSF"HCl, aprotinin, bestatin E-64, leupeptin, pepstatin; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, catalog #78430]) and then centrifuged at 16,000 x gfor 40 min For Western blot, samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing PKCδ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, 1:2000), V5 (Invitrogen, 1:5000) cytochrome c (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, 1:500), Smac (ProSci Poway, CA 1:500) or COX IV (Invitrogen, 1:1500).

In vitro mitochondria release assay

Isolated mitochondria were resuspended in the same isolation buffer at a concentration of 2.0 mg/ml. For the release assay [22], 40 μl mitochondria suspension was incubated with MG-132 at 30°C for 60 min Triton X-100 (0.2%, v/v) was included as positive control to release cytochrome c. After incubation, mitochondria were spun down and the supernatant was collected for the SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for cytochrome c (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, 1:500).

PKCδ kinase assay

The enzymatic activity of PKCδ was measured with an immunoprecipitation kinase assay, as described previously [23]. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (25-mM HEPES pH 7.5, 20-mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1-mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.3-M NaCl, 1.5-mM MgCl2, 0.2-mM EDTA, 0.5-mM DTT, 10-mM NaF, 4 μg/ml aprotinin, and 4 ^g/ml leupeptin). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 μ_g_ for 20 min to obtain the supernatant as cytosolic fraction. Cytosolic protein (500 |xg) was immunoprecipitated with 2 μg PKCδ antibody. The immunoprecipitates were washed 3 times with 2X kinase buffer (40 mM Tris pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 μM ATP, and 2.5 mM CaCl2), and resuspended in 20 μl of the same buffer. The reaction was initiated by adding 20 μl of reaction buffer (0.4 mg Histone H1, 50 ixg/mL phosphatidylserine, 4.1 μM dioleoyl-glycerol, and 5 μCi of [-γ-32P] ATP) to the resuspended immunoprecipi-tates. After 10-min incubation, samples were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. The radioactively labelled histone H1 was detected performed with a Phosphoimager system (Personal Molecular Imager, FX model, Bio-Rad Labs, Hercules, CA, USA) and analysed with Quantity One 4.2.0 software.

Plasmid construction and siRNA synthesis

Full-length wild-type (wt) PKCδ-GFP and PKCδD327A-GFP in pEGFP-N1 vector were obtained from Dr. Mary Reyland (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO). Full-length (PKCδ-FL), the regulatory fragment (PKCδ-RF) and the catalytic fragment (PKCδ-CF) of PKCδ were amplified from wt-PKCδ-GFP in the pEGFP-N1 vector, and PKCδD327A (caspase-3 cleavage-resistant mutant, PKCδ-CRM) was amplified from PKCδD327A-GFP in pEGFP-N1 vector by PCR. The PCR product was then cloned into the plenti6/V5-D-TOPO expression vector by following the procedure provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, CA). The primers used were: 5’-CACCATGGCACCCTTCCTGCTC3’ (forward primer for PKCδ-FL, PKCδ-CRM and PKCδ-RF) and 5’-AATGTCCAGGAATTGCTCAAAC-3’ (reverse primer for PKCδ-FL, PKCδ-CRM and PKCδ-CF), 5’-ACTCCCAGA-GACTTCTGGCTT-3’ (reverse primer for PKCδ-RF) and 5’-CACCATGAA-CAACGGGACCTGTGGCAA-3’ (forward primer for PKCδ-CF). To achieve mitochondria-targeted expression, PKCδ-RF and PKCδ-CF were cloned into the pCMV/Myc/Mito vector (Invitrogen) at Sal I and Not I sites by following standard cloning procedure. LacZ was cloned into the same vector to serve as a control. The primers used include: 5’-ATATGGGTCGA-CATGGCACCCTTCCTGCGCA-3’ (forward primer for PKCδ-RF), 5’-ATATATGTCGACATGAACAACGGGACCTATGGCAAGA-3’ (forward primer for PKCδ-CF), 5’ATATAGCGGCCGCAATGTCCAGGAATTGCTCAAAC 3’ (reverse primer for PKCδ-FL and PKCδ-CF) and 5’-ATATATGCGGCCG-CACTCCCAGAGACTTCTGGCT-3’ (reverse primer for PKCδ-RF).

Synthesis of siRNA duplex specifically targeting PKCδ and a non-specific siRNA was conducted as described in our previous publications [16, 24]. Chemically synthesized sense and antisense transcription templates contain a leader sequence complementary to the T7 promoter primer and an encoding sequence for siRNA. Following the annealing of the transcription templates with T7 promoter primer, hybridized DNA oligonucleotides were extended using Klenow DNA polymerase to form double-stranded transcription templates. An in vitro transcription reaction was then conducted with antisense or sense templates using T7 RNA polymerase, and the resulting RNA transcripts were annealed to form siRNA duplexes before removal of the leader sequence with single-strand-specific ribonuclease.

Cell transfection

The expression vectors (pLenti-PKCδ-CRM and pLenti-LacZ) were cotrans-fected with packaging plasmids provided by the manufacturer into 293 FT cells performed with Lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent for virus production (Invitrogen). The lentiviruses derived from the transfected 293 FT cells were used for transfection of pLenti-PKCδ-CRM and pLenti-LacZ in N27 cells. For stable expression, cells were selected with blasticidin (10.0 μg/ml).

Transient transfection was conducted performed with either AMAXA Nucleofector reagent (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) or the jetPEI™ DNA in vitro transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection Inc., New York, NY). For AMAXA electroporation, approximately 2×10 cells were suspended in 100 μl prepared Nucleofector™ solution V, and then mixed well with expression vectors (PKCδ-CF or PKCδ-RF), or siRNA (non-specific (NS) siRNA or PKCδ siRNA) before electroporation. Based on our previous studies [16], 25 nM siRNA-PKCδ and siRNA-NS were used for transfection. This concentration effectively suppresses PKCδ in N27 cells [16, 24]. Transfection efficiency was determined by pmaxGFP transfection, which was used as a control group for the caspase-3 assay. For transfection of mitochondria-targeted vectors, plasmids (2.0 |xg) were first mixed with 100-μl sterile sodium chloride (150 mM) to make the plasmid solution. The jetPEI™ solution was made by mixing 4.0 μl jetPEI™ reagent with 100 μl sterile sodium chloride. The jetPEI™ solution was then added to the plasmid solution and mixed well, and 200 μl jetPEI/DNA mixture was incubated at room temperature for 25 min before being added into culture wells. Transfected cells were viewed with confocal microscopy.

DNA fragmentation assay

DNA fragmentation was measured performed with a Cell Death Detection ELISA Plus Assay Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) as previously described [18]. Briefly, cells were resuspended with the lysis buffer provided in the assay kit. The lysate was centrifuged at 200 μ_g_, and 20 **μ,**l of supernatant was incubated for 2 hrs with the mixture of HRP-conjugated antibody cocktail that recognizes histones, and single- and double-stranded DNA. After washing away the unbound components, the final reaction product was measured colorimetrically, with ABTS as an HRP substrate performed with a spectrophotometer at 405 nm (490 nm as reference).

Immunocytochemistry and TUNEL staining

Immunofluorescence staining was conducted as described previously [25]. Briefly, 24 hrs after plasmid transfection, N27 cells cultured on coverslips pre-coated with poly-L-lysine were washed with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100, cells were incubated with blocking buffer (5% BSA, 5% goat serum in PBS) to minimize non-specific binding. For double staining, cells were incubated overnight with antibodies recognizing Myc tag (Abcam, Mouse monoclonal Ab 1:200) and cleaved caspase-3 (Cell signalling, Rabbit monoclonal Ab, 1:100). Then Myc tagged fusion proteins and cleaved caspase-3 were visualized with Cy3 conjugated anti-mouse and Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, respectively. The images were analysed performed with Nikon C1 confocal microscopy.

TUNEL staining for the transfected cells was conducted by following the protocol described by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Immunostaining with the Myc tag antibody was performed as described. The images were analysed with Nikon inverted fluorescence microscopy (Model TE-2000U).

Data analysis

Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M., and Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA) was used for data analysis. _P_-values were determined using Student's t-test for single comparisons of two samples. One-way anova followed by Dunnett's post-test was used to compare all groups with the control group or Bonferroni's test for comparison of selected groups. A significant difference between groups was defined as P< 0.05.

Results

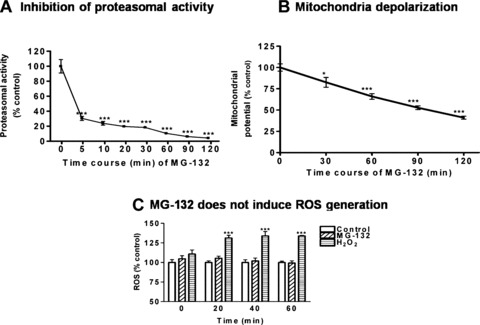

Proteasome inhibition by MG-132 precedes mitochondria depolarization

We used the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 to induce ubiquitin proteasome dysfunction in N27 dopaminergic cells. To systematically examine the effect of the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 on dopaminergic cells, we first performed a detailed time course analysis of chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity. As shown in Fig.1A, MG-132 exposure led to a rapid inhibition of proteasomal activity, with more than 70% inhibition within 5 min (P< 0.001). Next, we examined whether MG-132 has any effect on mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS generation. Determination of membrane potential by JC-1 showed a gradual and steady reduction starting at 30 min, with a 50% decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential over 120 min of MG-132 (Fig.1B). On the contrary, no significant elevation of ROS was noted during MG-132 treatment (Fig.1C) as measured by flow cytometry. To further confirm ROS production over prolonged exposure to MG-132, fluorescence microscopic analysis were performed. N27 cells were incubated with two different ROS sensitive dyes, dihydroethidine and CM-H2DCFDA, prior to treatment with MG-132 (0.1, 1, 3 or 5 μM) and ROS production was monitored over 6 hrs. As shown in Fig.1D, no significant change in ROS production was detected with either dye in N27 cells exposed to 5 μM MG-132 for 6 hrs. Additionally, lower doses (0.1–3.0 μM) did not generate any ROS (data not shown). However, we observed a significant ROS production in the 50 μM H2O2 treatment (positive control; Fig.1D). These data indicate that proteasomal inhibition, which precedes the dissipation of mitochondria membrane potential, is independent of oxidative insult.

Figure 1.

Proteasome inhibition by MG-132 precedes mitochondria depolarization. (A) Determination of proteasomal activity. N27 dopaminergic neu-ronal cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 0-120 min and chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity was assessed using Suc-LLVY-AMC. Enzymatic activity is presented as percentage of the control group. Values represent mean ± S.E.M for 6 samples in each group. (B) Flow cytometric determination of mitochondrial membrane potential. N27 cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 0–120 min. The intensity of red fluorescence for aggregated JC-1 and green fluorescence for monomer JC-1 was determined using flow cytometry, and the red/green ratio was used as the measurement of membrane potential. Values presented as mean ± S.E.M represent results of 4–6 individual samples. (C) Flow cytometric measurements for ROS. N27 cells following exposure to 5.0 μM MG-132 for 0, 20, 40 or 60 min, and intracellular ROS was quantified by flow cytometry using dihy-droethidine fluorescent probe. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. for 3–5 samples. 200 μM H2O2 was used as positive control. *P<0.05, ***P< 0.001 compared with control group. (D) ROS production using CM-H2DCFDA (DCF) or dihydroethidium (DHE) following 5.0 μM MG-132 treatment for 6 hrs. N27 cells cultured in 96-well plate were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 6 hrs. The cells were then incubated with DCF or DHE before visualization under fluorescence microscopy. H2O2 (50 μM)-treated cells were included as a positive control for ROS production.

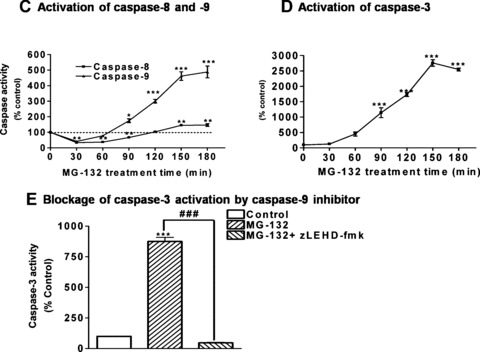

Proteasome inhibition by MG-132 triggers mitochondria-mediated apoptosis

Since MG-132 produced depolarization of mitochondria, we examined whether the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway is activated during proteasome inhibitor treatment in dopaminergic cells. First, we examined the effect of MG-132 on the release of proapoptotic molecules from mitochondria to cytosol. As shown in Fig.2A, cytosolic fractions from MG-132 treated N27 cells showed a time-dependent release of cytochrome c and Smac into cytosol in a similar temporal pattern (Fig.2A). No detection of the mitochondrial inner membrane protein COX IV in the cytosolic fraction indicated that the cytosolic fraction was free of mitochondrial contamination. To determine whether MG-132-induced release of proapoptotic factor results from a direct effect of the proteasome inhibitor on mitochondria, we measured cytochrome c release in isolated mitochondria following MG-132 treatment. The results showed no significant increase in cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria (Fig.2B), indicating that mitochondrial release of cytochrome c occurred in cells as a consequence of proteasome inhibition by MG-132, but not due to the direct stimulatory effect of MG-132 on mitochondria.

Figure 2.

Proteasome inhibition by MG-132 triggers mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. (A) Mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and Smac. N27 cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 0–120 min The cytosolic fractions prepared from the cells were resolved on 15% SDS-PAGE and blotted with antibodies against cytochrome c, Smac, β-actin, or COX IV. (B) Cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria. Mitochondria were isolated from N27 cells and resuspended in the isolation buffer at 2.0 mg/ml. An equal amount of mitochondrial suspension was incubated with 5.0- (lane 2) or 15.0 μM (lane 3) MG-132 for 1 hr, or with 0.2% Triton X-100 as positive control to release cyto c (lane 4). Lane 5 is input of isolated mitochondria. (C and D) Activation of caspase-8, -9, and -3. Cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 30, 60, 90, 120 or 180 min. The caspase-8, -9 and -3 activities were determined using fluorogenic substrates as described in the ‘Materials and methods’. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M for 8 samples. (E) Inhibition of caspase-3 activation by caspase-9 inhibitor LEHD-FMK. N27 cells were pre-treated with LEHD-FMK (50 μM) for 40 min before treatment with 5.0 μM MG-132 for an additional 120 min. The cells were collected for caspase-9 assay. Values represent mean ± S.E.M from 6 individual samples. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus control group.

Formation of the apoptosome complex by mitochondria-released cytochrome c, Apaf-1, and dATP/ATP is essential for the activation of initiator caspase-9, which then activates downstream effector caspase-3. As shown in Fig.2C, caspase-9 activity significantly increased 90 min after MG-132 treatment (P< 0.05), and then dramatically elevated three- to fourfold at 150 and 180 min (P< 0.001). We also measured caspase-8 activity to determine whether a non-mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway contributes to cell death during proteasome inhibitor treatment. The results showed only a minimal activation of caspase-8 activation only after the 120-min treatment of MG-132 (Fig.2C). Next, activity of the key effector caspase commonly known as caspase-3 was measured. MG-132 treatment resulted in a time-dependent increase starting at 90 min, and the activity was dramatically increased at 120 and 150 min (P< 0.001) (Fig.2D). Notably, caspase-3 activation was completely blocked by the caspase-9 inhibitor LEHD-fmk (Fig.2E), indicating that caspase-9 is the major upstream caspase responsible for MG-132-induced caspase-3 activation.

Proteasomal inhibition leads to proteolytic activation of PKCδ

Recently, we demonstrated that PKCδ is highly expressed in mouse nigral dopamine neurons [24], and that kinase can be proteolytically activated by caspase-3 during oxidative stress-induced dopaminergic degeneration [16, 18, 21, 23, 26]. Since we found a dramatic increase in caspase-3 activation during MG-132 treatment, we examined whether PKCδ is proteolytically activated in N27 cells. Western blot analysis revealed dose-dependent and time-dependent proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ following exposure to the 1–5 μM MG-132 for 1, 3 or 6 hrs (Fig.3A and C). The proteolytic cleavage was caspase-3-dependent, since it was diminished markedly by the caspase-3 inhibitor zDEVD-fmk (50 μM), as well as by the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (100 μM) (Fig.3A), indicating that the proteasome inhibitor induces caspase-3-dependent proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ. To assess the effect of proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ on its kinase activity, the PKCδ was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and an immunokinase assay was performed using [32P]-ATP and histone H1 substrate. Analysis of the intensity of radioactively labelled histone H1 bands indicated that MG-132 exposure results in a 282% increase in kinase activity of PKCδ (Fig.3B). Inhibition of PKCδ proteolytic cleavage either by caspase-3 inhibitors zDEVD-fmk (50 μM) or rottlerin (2.5 μM), or the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (100 μM) diminished its kinase activity, indicating that caspase-3 mediates PKCδ proteolytic cleavage and significantly activates its kinase activity (Fig.3B). In order to verify that proteasome inhibition triggers proteolytic activation of PKCδ, we used another highly specific and irreversible proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin. Treatment with lactacystin (5.0 μM) for 90 or 120 min also caused a marked increase in the proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ (Fig.3D), substantiating the proteolytic activation of PKCδ as a result of proteasomal inhibition in dopaminergic neuronal cells.

Figure 3.

Proteasomal inhibition by MG-132 leads to caspase-3-mediated proteolytic activation of PKCδ. (A) Proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ following MG-132 exposure. N27 cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 90 or 120 min. For the inhibitor study, cells were preincubated with 100 μM ZVAD or 50 μM DEVD-FMK for 40 min before the 120-min MG-132 treatment. Equal amounts of protein from individual samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody for PKCδ. Membranes were reprobed with β-actin antibody to ensure equal protein loading. (B) PKCδ kinase activity. N27 cells were exposed to 5.0 μM MG-132 for 120 min. For the inhibitor study, cells were pre-treated with 100.0 μM zVAD-fmk (+zVAD), 50.0 μM zDEVD-fmk (+DEVD) or 2.5 μM rottlerin (+Rottlerin) for 40 min. The cell lysates were prepared for PKCδ immunoprecipitation, and the kinase activity associated with immunoprecipitates was assayed by determining the intensity of the 32P-labelled H1. The arrow indicates the radioactively labelled H1. Densitometric analysis of the intensity of H1 bands is presented as percentage of control. The data represent the mean ± S.E.M. from 4 separate experiments. ***P< 0.001 comparing with vehicle-treated groups, and ###P< 0.001 comparing with MG-132 treatment group. (C) PKCδ cleavage following exposure to lower concentrations of MG-132. N27 cells were treated with 1.0 or 3.0 μM MG-132 for 1.0, 3.0 or 6.0 hrs. The cell lysates prepared from the treated cells were resolved in SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody against PKCδ. (D) Proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ following lactacystin treatment. N27 cells were treated with 5.0 μM lactacystin for 90 or 120 min and then cell lysates were prepared. Equal amount of protein from individual samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibody for PKCδ. Reprobing membrane with β-actin antibody was performed to ensure equal protein loading.

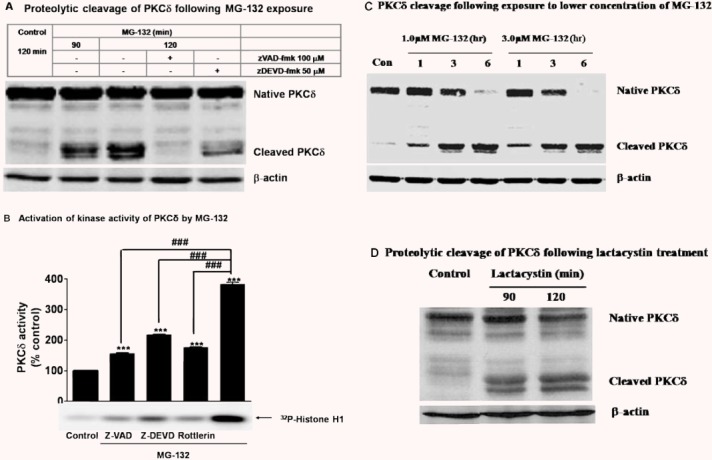

Activated PKCd as mediator for MG-132-induced mitochondria-mediated apoptosis

Next, we examined the role of proteolytically cleaved PKCδ in apoptosis by using PKCδ catalytic fragment (PKCδ-CF) and PKCδ regulatory fragment (PKCδ-RF). N27 cells were transfected with PKCδ-CF or PKCδ-RF, and the transfection efficiency was estimated by the cotransfected GFP plasmids (Fig.4A). Measurement of caspase-3 activity revealed a significant increase in the caspase-3 activity in PKCδ-CF-transfected cells as compared to RF-transfected or GFP-transfected cells, suggesting that kinase active PKCδ-CF is responsible for its proapoptotic effect in dopaminergic cells (Fig.4B). Additionally, pre-treatment with the PKCδ-specific inhibitor rottlerin also significantly attenuated MG-132-induced caspase-9 and -3 activation (Fig.4C and D), indicating that PKCδ activation indeed contributes to caspase activation following exposure to the proteasome inhibitor MG-132. However, MnTBAP, a superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic, failed to attenuate caspase-3 activation following MG-132 exposure (Fig.4E). Further, we and others have recently demonstrated a positive feedback activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 by proteolytically activated PKCδ during apoptotic cell death [21, 27]. Thus, a positive feedback loop would in part explain the observed inhibition of caspase-9 activation by rottlerin (Fig.4C). This finding suggests that the proapoptotic effect of PKCδ proceeds through the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway.

Figure 4.

Activation of caspase-3 by PKCδ-CF. (A) Twenty-four hours after transfection, phase contrast images and fluorescence images were taken to determine transfection efficiency. (B) Caspase-3 activity was measured as described in the ‘Materials and methods’ section (B). Values represent mean ± S.E.M. from 6 samples in each group. *P< 0.05 versus cells transfected with pmaxGFP alone; #P< 0.05 comparing the indicated groups. (C) and (D) Inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by rottlerin. N27 cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 120 min with or without rottlerin (2.5 μM) for a 40-min pre-treatment. Rottlerin treatment alone was also included in the experiment. Caspase-9 (C) and -3 activities (D) were assayed for the treated cells as described above. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. from 6 samples in each group. ***P< 0.001 comparing with vehicle-treated control cells. ###P< 0.001, comparison between the indicated groups. (E) Effect of MnTBAP on MG-132-induced caspase-3 activation. Cells were treated with either with 5.0 μM MG-132 alone or pre-treated with 10.0 μM MnTBAP 30 min prior to MG-132 treatment. The caspase-3 activity was determined as described previously. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. from 6 samples in each group. ***P< 0.001 comparing with vehicle-treated control cells.

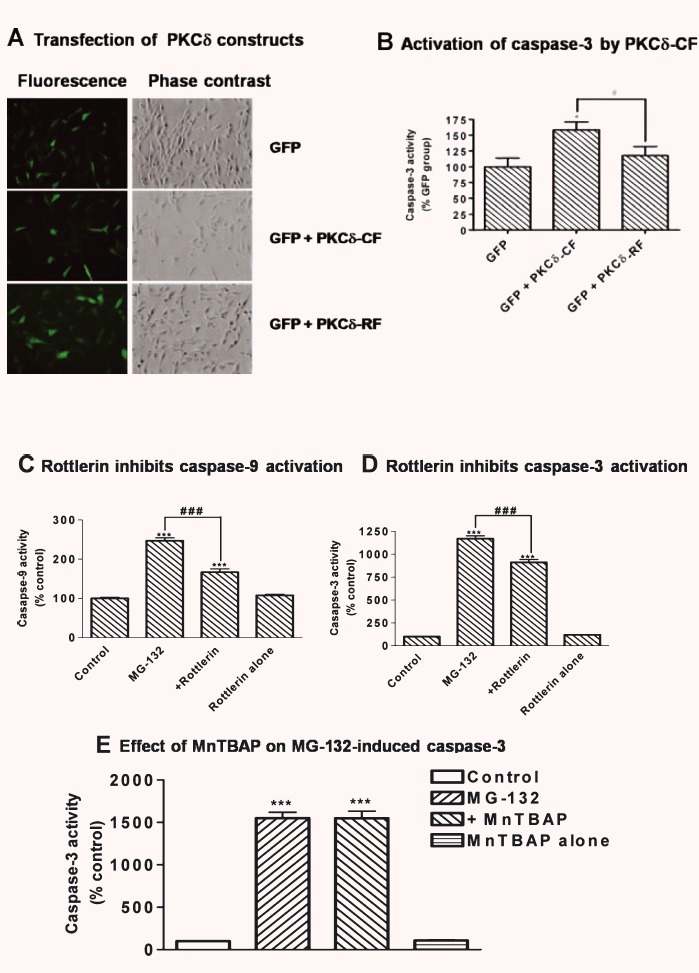

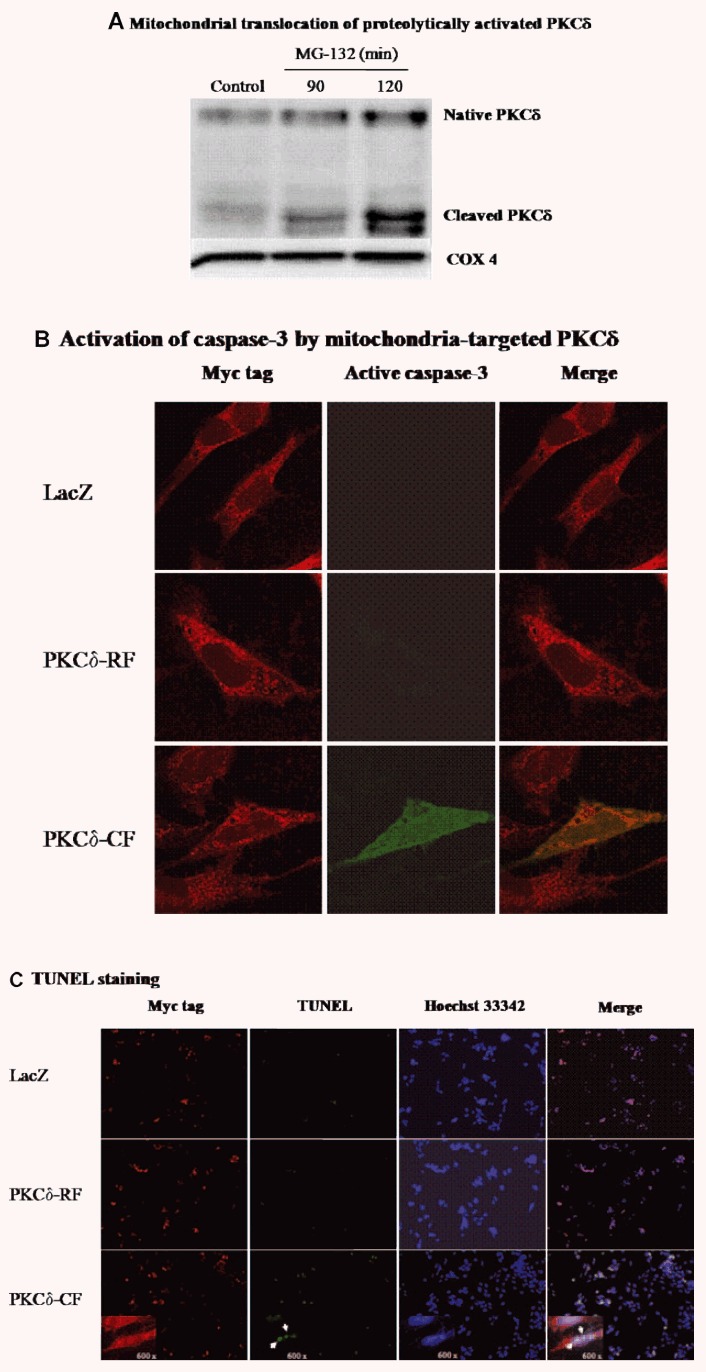

Mitochondrial translocation of active PKCδ induces apoptosis

Next, we examined whether activated PKCδ translocates to subcellular organelles to promote its proapoptotic function. As shown in Fig.5A, MG-132 treatment resulted in substantial and time-dependent accumulation of cleaved PKCδ in the mitochondrial fraction, and only a slight elevation of full-length PKCδ was observed. COX IV protein was used as marker of mitochondrial protein in the Western blot analysis (Fig.5A). Together, these results indicate proteasomal inhibition proteolytically activates PKCδ and causes translocation to mitochondria.

Figure 5.

Effect of mitochondria-localized active PKCδ on apoptosis. (A) Mitochondrial translocation of proteolyti-cally activated PKCδ. Mitochondrial fraction was prepared from cells exposed to 5.0 μM MG-132 for 90 or 120 min. Mitochondrial lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with PKCδ antibody, and the membrane was reprobed with COX IV to show equal protein loading. (B) Mitochondrial-localized active PKCδ activates caspase-3. After N27 cells were transfected with pCMV/myc/mito containing coding sequence for LacZ, PKCδ-RF or PKCδ-CF, double immunostaining was conducted using the mouse Myc tag primary antibody and rabbit active caspase-3 antibody. The Myc tag and active caspase-3 were visualized using confocal microscopy using Cy3 conjugated anti-mouse (red) and Alexa-488 conjugated anti-rabbit (green) secondary antibodies. (C) TUNEL staining in the transfected cells. After transfection for 24 hrs, cells were subjected to TUNEL staining (green) and immunostaining with Myc tag antibody (red). The images were analysed with fluorescence microscopy. The inserts show higher magnification pictures (600x).

To understand whether mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ-CF is functionally related to its proapoptotic effect, mitochondria-targeted expression of PKCδ-CF and PKCδ-RF was achieved performed with pCMV/myc/mito vector. Double immunostaining for myc tag (red) and active caspase-3 (green) revealed activation of caspase-3 in the PKCδ-CF transfected cells, but not in the PKC-RF or LacZ transfected cells (Fig.5B). Also, cells transfected with PKCδ-CF, but not PKCδ-RF or LacZ, were TUNEL positive (Fig.5C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ-CF can amplify the apoptotic cascade during proteasomal dysfunction.

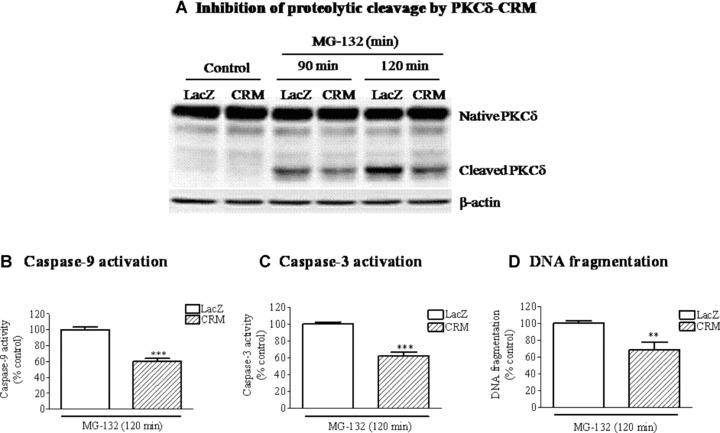

Suppression of PKCδ proteolytic activation protects cells from mitochondria-mediated apoptosis following proteasome inhibitor exposure

To further substantiate that proteolytic activation is primarily responsible for the feedback amplification of mitochondria-mediated apoptotic signalling during dopaminergic apoptosis, a caspase-3 cleavage-resistant mutant of PKCδ (PKCδ7, PKCδ-CRM) was introduced into N27 cells using a lentivirus expression system and cells stably expressing PKCδ-CRM were generated. PKCδ-CRM expressing cells are more resistant to MG-132-induced PKCδ proteolytic cleavage (Fig.6A). Furthermore, the PKCδ-CRM cells were more resistant to MG-132-induced mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, as demonstrated by the significant reduction of caspase-9, caspase-3 activation, and DNA fragmentation compared to LacZ-transfected cells (Fig.6B-D). Together these results demonstrate proteolytic activation of PKCδ promotes apoptotic cell death via a feedback amplification of the mitochondria-mediated caspase cascade.

Figure 6.

Suppression of PKCδ proteolytic activation protects cells from mitochondria-mediated apoptosis during proteasome inhibition. (A) Suppression of PKCδ proteolytic cleavage by PKCδ-CRM. N27 cells stably transfected with LacZ (as control) and PKCδ-CRM were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132. Equal amounts of protein from the LacZ and CRM cells were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblot-ting with PKCδ antibodies. The membrane was reprobed and blotted with β-actin antibody. (B, C and D) Suppression of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by PKCδ-CRM. Caspase-9 activity (B), caspase-3 activity (C) and DNA fragmentation (D) were determined for LacZ and CRM cells exposed to MG-132 for 120 min. The values are expressed as the percentage of control cells. Results represent mean ± S.E.M from 6–8 samples. *P< 0.05 and ***P< 0.001.

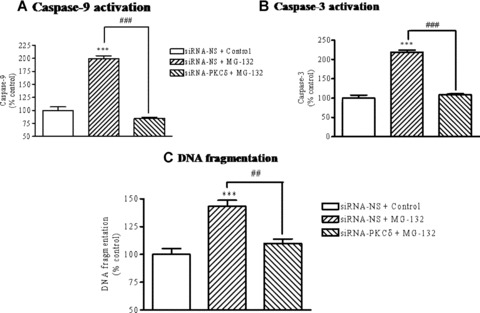

Inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by PKCδ siRNA

To further confirm the critical role of PKCδ in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis during proteasome inhibition, we used a RNAi approach. siRNA duplex specifically targeting PKCδ[16, 24] was introduced into N27 cells using electroporation transfection, and then caspase-9, caspase-3, and DNA fragmentation were assayed. The results revealed a remarkable inhibitory effect of siRNA-PKCδ on the activation of caspase-9 (Fig.7A), caspase-3 (Fig.7B) and DNA fragmentation (Fig.7C). Nonspecific siRNA treatment did not alter these apoptotic markers. Again, a positive feedback loop would in part explain the observed inhibition of caspase-9 activation by PKCδ siRNA (Fig.7A).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cascade by PKCδ siRNA. N27 cells were transfected with non-specific siRNA (siRNA-NS) or siRNA for PKCδ (siRNA-PKCδ). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 5.0 μM MG-132 for 120 min and then activities of caspase-3 (A) and caspase-9 (B) and DNA fragmentation (C) were assayed. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. from 5 samples in each group. ***P< 0.001 compared to vehicle-treated control cells. ##P <0.01, ###P <0.001, comparison between the indicated groups.

Collectively, these results clearly confirm that PKCδ regulates the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cascade following proteasomal dysfunction in dopaminergic neuronal cells.

Discussion

The present study reveals an important regulatory role of PKCδ in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells following proteasome inhibition. We demonstrated activation of the mitochondria-mediated apoptosis cascade and proteolytic activation of PKCδ during proteasome inhibition. Importantly, we found that proteolytic activation and mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ underlie its positive feedback amplification of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis during proteasome dysfunction in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells. This mitochondria-dependent proapop-totic capacity of PKCδ sheds light on degenerative processes of dopaminergic neurons mediated by UPS dysfunction in PD.

In addition to mitochondria dysfunction and oxidative stress, UPS dysfunction has recently been recognized as a key pathophysiological process of PD. Previous studies have revealed that the substantia nigra particularly suffers from UPS dysfunction in the brains of patients with sporadic PD [28, 29]. Mutations in genes of the ubiquitin ligase Parkin and the deubiquitin enzyme UchL-1 in familial PD have provided further evidence for the contributory roles of impaired UPS function in PD [2, 30, 31]. Notably, protea-some inhibitors have been shown to reproduce some key features of PD, including neuronal death [32–34]. However, underlying cell death mechanisms during UPS dysfunction remain to be determined. Recently, we and other have shown that dopaminergic neurons in mesencephalic culture are more susceptible to proteasomal inhibition than non-dopaminergic cells [15, 28, 32, 33, 35].

Additionally, we have shown dopaminergic neurons in nigral regions are more sensitive than non-dopaminergic cells following intra-nigral injection of MG-132 [15]. In the present study, we showed substantial reduction of proteasomal activity shortly after exposure to a low dose (5.0 μM) of MG-132 (70%, Fig.1A), which was followed by progressive dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig.1B). Mitochondrial depolarization has been extensively observed during apoptosis, concurrent with mitochondrial release of proapoptotic molecules in apoptosis models, including PD models [36]. Following MG-132 treatment, cytosolic cytochrome c and Smac levels progressively increased in N27 cells (Fig.2A). It appears that mitochondrial release of cytochrome c occurred as a consequence of proteasome inhibition by MG-132, but not due to a direct stimulatory effect of MG-132 on mitochondria, because incubation of isolated mitochondria with MG-132 failed to trigger mitochondrial release of cytochrome c (Fig.2B).

Several proteins important for regulation of mitochondria-dependent apoptosis, such as p53, Bax, PUMA, and BAD, have previously been shown to be degraded by the proteasome. Presumably, the inadequate proteasomal degradation of these proteins increases their mitochondrial association or translocation, and thus actively contributes to the release of cytochrome c and resulting mitochondrial functional impairment [37]. However, we cannot rule out the role of other cellular mechanisms such as lipoxygenases, ER stress and autophagy in proteasome inhibitors-induced cell death processes. Recently, lipoxygenases have been shown to play a key role in organelle degradation and mitochondria-dependent neuronal cell death [38, 39]. It has also been shown that accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins can facilitate the formation of macroautophagy, a process in which impaired organelles including mitochondria, are targeted for degradation by lysosome [40]. Presently, it is unclear whether proteasome inhibition in neuronal cells can trigger autophagy in dopaminergic neurons. Future studies will clarify the integrative role of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis in the neurodegenerative process following proteasomal dysfunction. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that proteasome inhibition activates mitochondria-mediated apoptotic signalling in dopaminergic cells.

Association of cytosolic cytochrome c with Apaf-1 and dATP/ATP as the apoptosome complex is essential for the activation of initiator and effector caspases. Following MG-132 treatment, significant activation of caspase-9 and -3 but not caspase-8 was observed for 90 min (Fig.2C and D). Unexpectedly, cas-pase-8 and -9 activities were slightly but significantly reduced at early stages (up to 60 min) of MG-132 treatment (Fig.2C), presumably due to compensatory action of anti-apoptotic proteins such as IAPs or Mcl-1 upon proteasome inhibition [41, 42]. In comparison to caspase-9 and -3 activation, the slight activation of caspase-8 at late time-points (150 and 180 min) agrees with previous reports demonstrating caspase-8 activation resulting from caspase-9 and -3 activation [43]. It appears that caspase-8 plays only a minor role in proteasomal dysfunction in dopaminergic cells. Notably, the apoptotic cell death during MG-132 was predominantly through the mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway, since caspase-3 activation was completely suppressed by the caspase-9 inhibitor LEHD-FMK (Fig.2E), indicating that caspase-9 is the major upstream initiator caspase during proteasomal dysfunction.

Protein kinase C8 (PKCδ), a member of the novel PKC family, has a structurally and functionally distinct N-terminal regulatory fragment, a C-terminal catalytic fragment, and a medial hinge region [44]. Proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ at the hinge region by caspase-3 represents one of the primary means of its activation, in addition to membrane translocation or phosphorylation [17]. Proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ physically dissociates the auto-inhibitory regulatory fragment from its catalytic fragment, thus permanently activating its kinase activity. Tyr-311 phosphorylation of PKCδ is important for its caspase-3-mediated proteolytic cleavage [45]. Previously, we showed that proteolytically activated PKCδ plays a key role in mediating oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells [16, 18, 21, 46]. The possible mechanisms of positive feedback activation of caspase-3 in dopaminergic neuronal cells are yet to be identified. Although phosphorylation of caspase-3 by full-length PKCδ has been shown to increase enzymatic activity of caspase-3 in monocytes [47], we did not find caspase-3 phosphorylation by PKCδ in dopaminergic cells (unpublished observations). It appears that PKCδ amplifies caspase-3 activation via distinct mechanisms when it is proteolytically activated in dopaminergic neuronal cells. Proteolytic activation of PKCδ in dopaminergic cells appears to depend on caspase-3 activation in N27 cells exposed to proteasome inhibitors (Fig.3A-C). The direct proapoptotic effect of PKCδ-CF is manifested by the elevation of caspase-3 activity in PKCδ-CF transfected cells (Fig.4B), consistent with apoptotic function of PKCδ proteolytic activation. In addition, PKCδ likely enhances activation of caspase-9, which further activates the downstream effector caspase-3, since the PKCδ-specific inhibitor rottlerin attenuates activation of caspase-3 and upstream initiator caspase-9, at least in our study (Fig.4C and D). Emerging evidence has indicated that rottlerin, a previously well-accepted specific inhibitor for PKCδ, actually possesses some biological function other than PKCd inhibition, such as uncoupling mitochondria [48]. Rottlerin has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of PKCd, with an IC50 of 3–6 μM, whereas the Ki for other PKC isoforms are 5–10 times higher. Other studies have shown rottlerin may inhibit other kinases such as CaM kinase III, PRAK and MAPKAP-K2 as well as other cellular targets [48–52]. Since rottlerin is not a highly specific inhibitor for PKCδ, we used multiple approaches including siRNA, dominant-negative mutant and cleavage-resistant mutants in our studies. In the present study, effective suppression of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis either by PKCδ cleavage-resistant mutant or by PKCd siRNA clearly suggests PKCδ activation truly underlies its pro-apoptotic capacity following MG-132 exposure.

Induction of ROS generation was observed during prolonged exposure to proteasome inhibitors Bortezomib [53], MG-132, lactacystin [54], and PS-341 [55] in several non-neuronal cell lines. Oxidative stress has been demonstrated to activate caspase-3 and PKCδ in N27 cells [18, 23]. In an attempt to determine whether dopaminergic apoptosis following MG-132 exposure involves oxidative stress, ROS generation was measured; no significant increase in ROS generation was noted (Fig.1C and D). Additionally, the antioxidant MnTBAP, which has been previously shown to effectively inhibit caspase-3 activation during oxidative stress in N27 cells [18], failed to attenuate caspase-3 activation induced by MG-132 (Fig.4E). Our data suggest that ROS generation plays a negligible role in apoptotic cell death following proteasome inhibition in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells.

The mitochondria-dependent proapoptotic capacity of active PKCδ, as indicated by suppression of caspase-9 activation by rottlerin, was accompanied by mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ. This translocation of proteolytically activated PKCδ following proteasome inhibition is consistent with the existing hypothesis that the mitochondrion is a major target organelle that determines the fate of cell survival and death [56]. PKCδ has been shown to accumulate in nuclei [57], golgi [58] and endoplasmic reticulum [59] in various cell types. In an attempt to determine whether mitochondrial translocation of proteolytically activated PKCδ underlies its proapoptotic effect, marked activation of caspase-3 was noted in the N27 cells expressing mitochondria targeted PKCδ-CF (Fig.5B), but not PKCδ-RF or LacZ. This indicates that mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ-CF possibly underlies its feedback amplification of caspase activation. Considering the multiple pathways that lead to PKCδ activation, we conducted additional experiments to verify that PKCδ proteolytic activation mediates its mitochondria-dependent proapoptotic effect. Expression of a caspase-3 cleavage-resistant mutant of PKCδ (PKCδ-CRM), which effectively inhibited the proteolytic cleavage of endogenous PKCδ (Fig.6A), significantly attenuated the activation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis triggered by MG-132 (Fig.6B-D). These findings are consistent with a recent study showing that PKCδ-CRM reduces the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c in UV-challenged keratinocytes [46]. Phosphorylation of mitochondrial resident proteins by active PKCδ likely underlies its effect on mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Several mitochondrial proteins have been characterized as candidate substrates of PKCδ, including phospholipid scramblase [60] and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase [61]. Likely, elevated levels of BAD, due to its incomplete degradation by the proteasome, also participates in the mitochondria-dependent proapoptotic effect of PKCδ in dopaminergic cells, given the previous finding that PKCδ mitochondrial translocation is accompanied by an increase in the level of BAD following cardiac ischaemia [62]. We also recently reported that systemic administration of PKCδ inhibitor alleviates the nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration in an MPTP-induced animal model of PD; PKCδ inhibitor has been previously shown to supress dopaminergic apoptosis involving proteolytic activation of PKCδ in the N27 cells [18, 24]. Therefore, we believe that PKCδ inhibition is expected to exert a similar neuroprotection in an MG-132 in vivo model. We are currently investigating the role of PKCδ using RNAi-based gene knockdown and PKCδ-knockout animals. Future studies should focus on identifying the key target molecule in mitochondria that contributes to amplification of apoptotic cell death following proteasome dysfunction.

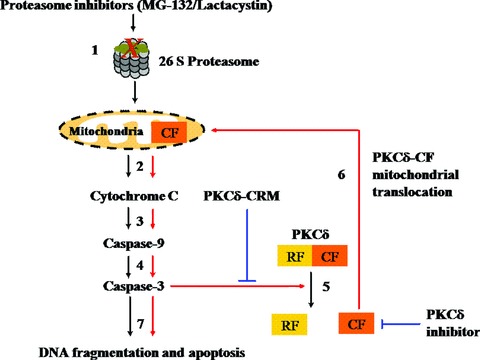

As summarized in Fig.8, the present study demonstrates that proteolytic activation and mitochondrial translocation of PKCδ underlies its feedback activation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis during proteasome dysfunction in mesencephalic dopaminergic neuronal cells. The high expression of PKCδ in nigral dopaminergic neurons and the convergence of proteasomal and mitochondrial dysfunction at the level of PKCδ demonstrate that the kinase is a crucial proapoptotic signalling molecule in dopaminergic degenerative processes. This knowledge advances our understanding of the pathogenesis of nigrostriatal degeneration and validates PKCδ as potential target for therapeutic intervention of PD.

Figure 8.

Proposed model delineating the apoptosis signalling cascades during proteasome inhibition in dopaminergic neuronal cells. (1) Proteasomal inhibition by MG-132 or lactacystin; (2) Cytochrome c release; (3) Caspase-9 activation; (4) Caspase-3 activation; (5) PKCδ proteolytic activation; (6) Positive feedback mitochon-drial translocation of proteolytically activated PKCδ; (7) DNA fragmentation and apoptotic cell death. Negative regulation of PKCδ activity by PKCδ-CRM or PKCδ inhibitor is indicated by the solid blue lines. Positive feedback activation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis cascades is indicated by red solid lines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants NS38644, ES10586 and NS45133. W. Eugene and Linda Lloyd Endowed Chair to AGK is also acknowledged. The authors acknowldege Ms. Keri Henderson for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiqui-tin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun F, Kanthasamy A, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Environmental neurotoxic chemicals-induced ubiquitin proteasome system dysfunction in the pathogenesis and progression of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;114:327–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNaught KS, Olanow CW. Proteolytic stress: a unifying concept for the etiopathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;(53 Suppl 3):S73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.10512. ; discussion S84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fornai F, Schluter OM, Lenzi P, Gesi M, Ruffoli R, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Busceti CL, Pontarelli F, Battaglia G, Pellegrini A, Nicoletti F, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A, Sudhof TC. Parkinson-like syndrome induced by continuous MPTP infusion: convergent roles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3413–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409713102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng BY, Iravani MM, Lin ST, Irifune M, Kuoppamaki M, Al-Barghouthy G, Smith L, Jackson MJ, Rose S, Medhurst AD, Jenner P. MPTP treatment of common marmosets impairs proteasomal enzyme activity and decreases expression of structural and regulatory elements of the 26S proteasome. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1766–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manning-Bog AB, Reaney SH, Chou VP, Johnston LC, McCormack AL, Johnston J, Langston JW, Di Monte DA. Lack of nigrostriatal pathology in a rat model of proteasome inhibition. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:256–60. doi: 10.1002/ana.20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schapira AH, Cleeter MW, Muddle JR, Workman JM, Cooper JM, King RH. Proteasomal inhibition causes loss of nigral tyrosine hydroxylase neurons. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:253–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.20934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNaught KS, Olanow CW. Proteasome inhibitor-induced model of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:243–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.20936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNaught KS, Perl DP, Brownell AL, Olanow CW. Systemic exposure to proteasome inhibitors causes a progressive model of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:149–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bove J, Zhou C, Jackson-Lewis V, Taylor J, Chu Y, Rideout HJ, Wu DC, Kordower JH, Petrucelli L, Przedborski S. Proteasome inhibition and Parkinson's disease modeling. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:260–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kordower JH, Kanaan NM, Chu Y, Suresh Babu R, Stansell J, 3rd, Terpstra BT, Sortwell CE, Steece-Collier K, Collier TJ. Failure of proteasome inhibitor administration to provide a model of Parkinson's disease in rats and monkeys. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:264–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNaught KS, Bjorklund LM, Belizaire R, Isacson O, Jenner P, Olanow CW. Proteasome inhibition causes nigral degeneration with inclusion bodies in rats. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1437–41. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200208070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miwa H, Kubo T, Suzuki A, Nishi K, Kondo T. Retrograde dopaminergic neuron degeneration following intrastriatal proteasome inhibition. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun F, Anantharam V, Latchoumycandane C, Zhang D, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Proteasome inhibitor MG-132 induces dopaminergic degeneration in cell culture and animal models. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:807–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Kaul S, Zhang D, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Suppression of caspase-3-dependent proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta by small interfering RNA prevents MPP+-induced dopaminer-gic degeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:406–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanthasamy AG, Anantharam V, Zhang D, Latchoumycandane C, Jin H, Kaul S, Kanthasamy A. A novel peptide inhibitor targeted to caspase-3 cleavage site of a proapoptotic kinase protein kinase C delta (PKCdelta) protects against dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in Parkinson's disease models. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1578–89. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaul S, Kanthasamy A, Kitazawa M, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Caspase-3 dependent proteolytic activation of protein kinase C delta mediates and regulates 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+)-induced apoptotic cell death in dopaminergic cells: relevance to oxidative stress in dopaminergic degeneration. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1387–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews ZB, Horvath B, Barnstable CJ, Elsworth J, Yang L, Beal MF, Roth RH, Matthews RT, Horvath TL. Uncoupling protein-2 is critical for nigral dopamine cell survival in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:184–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Wagner J, Kaul S, Kanthasamy AG. Caspase-3-dependent proteolytic cleavage of protein kinase Cdelta is essential for oxidative stress-mediated dopaminergic cell death after exposure to methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1738–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01738.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell. 1998;94:481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitazawa M, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy AG. Dieldrin induces apoptosis by promoting caspase-3-dependent proteolytic cleavage of protein kinase Cdelta in dopaminergic cells: relevance to oxidative stress and dopaminergic degeneration. Neuroscience. 2003;119:945–64. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang D, Kanthasamy A, Yang Y, Anantharam V. Protein kinase Cdelta negatively regulates tyrosine hydroxylase activity and dopamine synthesis by enhancing protein phosphatase-2A activity in dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5349–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4107-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun F, Anantharam V, Latchoumycandane C, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Dieldrin induces ubiquitin-proteasome dysfunction in alpha-synuclein overexpressing dopaminergic neuronal cells and enhances susceptibility to apoptotic cell death. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:69–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase Cdelta is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:46–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyland ME, Anderson SM, Matassa AA, Barzen KA, Quissell DO. Protein kinase C delta is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19115–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNaught KS, Belizaire R, Jenner P, Olanow CW, Isacson O. Selective loss of 20S proteasome alpha-subunits in the substantia nigra pars compacta in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326:155–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNaught KS, Jenner P. Proteasomal function is impaired in substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:191–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olanow CW, McNaught KS. Ubiquitin-proteasome system and Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1806–23. doi: 10.1002/mds.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:57–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNaught KS, Mytilineou C, Jnobaptiste R, Yabut J, Shashidharan P, Jennert P, Olanow CW. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system causes dopaminergic cell death and inclusion body formation in ventral mesencephalic cultures. J Neurochem. 2002;81:301–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rideout HJ, Lang-Rollin IC, Savalle M, Stefanis L. Dopaminergic neurons in rat ventral midbrain cultures undergo selective apoptosis and form inclusions, but do not up-regulate iHSP70, following protea-somal inhibition. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1304–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rideout HJ, Larsen KE, Sulzer D, Stefanis L. Proteasomal inhibition leads to formation of ubiquitin/alpha-synuclein-immunoreactive inclusions in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2001;78:899–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reaney SH, Johnston LC, Langston WJ, Di Monte DA. Comparison of the neuro-toxic effects of proteasomal inhibitors in primary mesencephalic cultures. Exp Neurol. 2006;202:434–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ly JD, Grubb DR, Lawen A. The mitochondrial membrane potential (deltapsi(m)) in apoptosis; an update. Apoptosis. 2003;8:115–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1022945107762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang HG, Wang J, Yang X, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Regulation of apoptosis proteins in cancer cells by ubiquitin. Oncogene. 2004;23:2009–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grullich C, Duvoisin RM, Wiedmann M, van Leyen K. Inhibition of 15-lipoxyge-nase leads to delayed organelle degradation in the reticulocyte. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:51–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Leyen K, Arai K, Jin G, Kenyon V, Gerstner B, Rosenberg PA, Holman TR, Lo EH. Novel lipoxygenase inhibitors as neuroprotective reagents. J Neurosci Res. 2007;86:904–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shacka JJ, Roth KA, Zhang J. The autophagy-lysosomal degradation pathway: role in neurodegenerative disease and therapy. Front Biosci. 2008;13:718–36. doi: 10.2741/2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Fang S, Jensen JP, Weissman AM, Ashwell JD. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteasomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science. 2000;288:874–7. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nijhawan D, Fang M, Traer E, Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X. Elimination of Mcl-1 is required for the initiation of apoptosis following ultraviolet irradiation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1475–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.1093903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viswanath V, Wu Y, Boonplueang R, Chen S, Stevenson FF, Yantiri F, Yang L, Beal MF, Andersen JK. Caspase-9 activation results in downstream caspase-8 activation and bid cleavage in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9519–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09519.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinberg SF. Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase Cdelta. Biochem J. 2004;384:449–59. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul S, Anantharam V, Yang Y, Choi CJ, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the proteolytic activation of protein kinase Cdelta in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28721–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Costa AM, Denning MF. A caspase-resistant mutant of PKC-delta protects keratinocytes from UV-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:224–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voss OH, Kim S, Wewers MD, Doseff AI. Regulation of monocyte apoptosis by the protein kinase Cdelta-dependent phosphorylation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17371–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin: an inappropriate and ineffective inhibitor of PKCdelta. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:453–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gschwendt M, Muller HJ, Kielbassa K, Zang R, Kittstein W, Rincke G, Marks F. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:93–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Samokhin GP, Jirousek MR, Ways DK, Henriksen RA. Effects of protein kinase C inhibitors on thromboxane production by thrombin-stimulated platelets. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;386:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin is a mitochondrial uncoupler that decreases cellular ATP levels and indirectly blocks protein kinase Cdelta tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37986–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ling YH, Liebes L, Zou Y, Perez-Soler R. Reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the apoptotic response to Bortezomib, a novel proteasome inhibitor, in human H460 non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33714–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu HM, Chi KH, Lin WW. Proteasome inhibitors stimulate activator protein-1 pathway via reactive oxygen species production. FEBS Lett. 2002;526:101–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fribley A, Zeng Q, Wang CY. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 induces apoptosis through induction of endoplasmic reticu-lum stress-reactive oxygen species in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9695–704. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9695-9704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denning MF, Wang Y, Tibudan S, Alkan S, Nickoloff BJ, Qin JZ. Caspase activation and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential during UV radiation-induced apoptosis of human keratinocytes requires activation of protein kinase C. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:40–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cross T, Griffiths G, Deacon E, Sallis R, Gough M, Watters D, Lord JM. PKC-delta is an apoptotic lamin kinase. Oncogene. 2000;19:2331–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kajimoto T, Shirai Y, Sakai N, Yamamoto T, Matsuzaki H, Kikkawa U, Saito N. Ceramide-induced apoptosis by transloca-tion, phosphorylation, and activation of protein kinase Cdelta in the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12668–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zrachia A, Dobroslav M, Blass M, Kazimirsky G, Kronfeld I, Blumberg PM, Kobiler D, Lustig S, Brodie C. Infection of glioma cells with Sindbis virus induces selective activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta. Implications for Sindbis virus-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23693–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He Y, Liu J, Grossman D, Durrant D, Sweatman T, Lothstein L, Epand RF, Epand RM, Lee RM. Phosphorylation of mitochon-drial phospholipid scramblase 3 by protein kinase C-delta induces its activation and facilitates mitochondrial targeting of tBid. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:1210–21. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Churchill EN, Murriel CL, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D, Szweda LI. Reperfusion-induced translocation of deltaPKC to cardiac mitochondria prevents pyruvate dehydrogenase reactivation. Circ Res. 2005;97:78–85. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173896.32522.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murriel CL, Churchill E, Inagaki K, Szweda LI, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase Cdelta activation induces apoptosis in response to cardiac ischemia and reperfusion damage: a mechanism involving BAD and the mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47985–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]