Association Between Media Use in Adolescence and Depression in Young Adulthood: A Longitudinal Study (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Dec 20.

Abstract

Context

Although certain media exposures have been linked to the presence of psychiatric conditions, few studies have investigated the association between media exposure and depression.

Objective

To assess the longitudinal association between media exposure in adolescence and depression in young adulthood in a nationally representative sample.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting and Participants

We used the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to investigate the relationship between electronic media exposure in 4142 adolescents who were not depressed at baseline and subsequent development of depression after 7 years of follow-up.

Main Outcome Measure

Depression at follow-up assessed using the 9-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Results

Of the 4142 participants (47.5% female and 67.0% white) who were not depressed at baseline and who underwent follow-up assessment, 308 (7.4%) reported symptoms consistent with depression at follow-up. Controlling for all covariates including baseline Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale score, those reporting more television use had significantly greater odds of developing depression (odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.08 [1.01-1.16]) for each additional hour of daily television use. In addition, those reporting more total media exposure had significantly greater odds of developing depression (1.05 [1.0004-1.10]) for each additional hour of daily use. We did not find a consistent relationship between development of depressive symptoms and exposure to videocassettes, computer games, or radio. Compared with young men, young women were less likely to develop depression given the same total media exposure (odds ratio for interaction term, 0.93 [0.88-0.99]).

Conclusion

Television exposure and total media exposure in adolescence are associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms in young adulthood, especially in young men.

Depression is the Leading cause of nonfatal disability worldwide.1 Because onset of depression is common in adolescence and young adulthood,2,3 it coincides with a pivotal period of physical and psychologic development and can lead to poorer psychosocial functioning, lower life and career satisfaction, more interpersonal difficulty, greater need for social support, more comorbid psychiatric conditions, and increased risk of suicide.4,5 Even after recovery from an initial episode of depression, affected young people frequently experience substantial psychosocial impairment and are at increased risk of recurrence of episodes of depression.4,5

The development of depression in adolescence may be understood as a biopsychosocial, multifactorial process influenced by risk and protective factors including temperament, genetic heritability, parenting style, cognitive vulnerability, stressors (eg, trauma exposure or poverty), and interpersonal relationships.2,3,5-7 It is plausible that exposure to electronic media may be one of the factors that influence development of depression. This exposure is massive: when accounting for multitasking, current adolescent media use is estimated at 81/2 hours per day.8

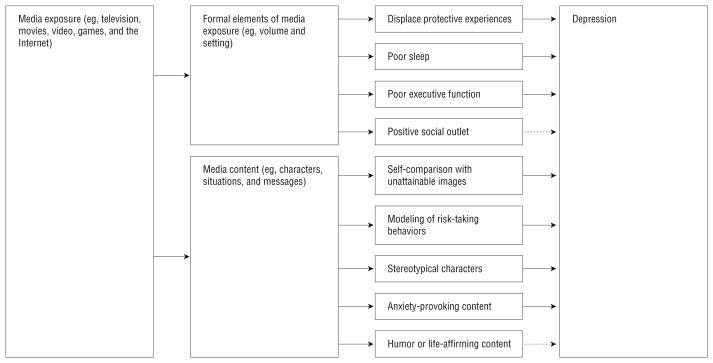

There are many different mechanisms by which media exposure may influence development of depression (Figure 1). In terms of the sheer volume of exposure, adolescents who spend excessive time engaging with media may not have as much opportunity as their peers to cultivate protective experiences that require active social, intellectual, or athletic engagement.6,7,9,10 Related to this, excessive media exposure often occurs at night and can displace sleep, which is valuable for normal cognitive and emotional development.11-14 It has also been suggested that early media exposure can interfere with optimal development of executive function,15 potentially contributing to vulnerability to cognitive distortions that have been associated with depression.16,17 It should also be noted, however, that adolescents often use media in social settings, which may offer a social outlet that protects against depression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical relationships between media exposure and depression. Dashed lines represent negative relationships (ie, positive social elements of media consumption and exposure to humor or life-affirming content may decrease the likelihood of developing depression).

Media content may also lead to depression more directly. Cultural messages transmitted through media may affect other behaviors related to mental health such as eating disorders and aggressive behavior,18,19 and media exposure may similarly contribute to development of depression through reinforcement of depressogenic cognitions.20 For example, certain electronic media exposures are saturated with highly idealized characters and situations, and constant comparison of one's self with these unattainable images may result in depression.16,20-22 Related to this, media messages often contain simplistic stereotypical portrayals of sociodemographic factors such as sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and occupation.23-27 Because adolescence is an important time of self-definition, exposure to such simplistic portrayals can interfere with normal identity development, potentially producing dysphoria.28 Other media exposures are highly negative and anxiety provoking,29-31 and repeated exposure to these messages may engender a negative and fearful perception of the world, which can also result in depression.16,17 In addition, media commonly used by adolescents contain multiple references to risky behavior including substance use or abuse, violence, and sex,32-37 and adolescents who engage in these behaviors may come to regret them and become prone to dysphoria.38-40

However, it should also be noted that exposure to certain media content might reduce the likelihood of developing depression.41,42 Humor, an important element of entertainment, is frequently portrayed in television programs, popular songs, movies, and video games.36,43-45 Biomedical studies have shown that mirthful laughter can reduce stress,46 and laughter therapy has emerged as a possible therapeutic method.41 Humor has even been found to be beneficial among depressed and terminally ill patients.47,48 Life-affirming media messages may similarly protect against depression.

Although some have investigated a relationship between electronic media and mental health, these studies generally have been cross-sectional and have focused on anxiety. For example, some studies have shown an association between posttraumatic stress disorder and exposure to television images of terrorist incidents.49,50 Similarly, excessive use of certain media has been associated with social anxiety and decline in interpersonal relationships.9,51 However, there is limited information about the relationship between media exposure and future development of depression in a nationally representative population.

The purpose of this study was to assess empirically the association between electronic media exposure in adolescence and subsequent development of depressive symptoms in young adulthood. Our a priori hypothesis was that excessive volume of television viewing during the adolescent years is associated with increased development of depression in young adulthood. On the basis of theoretical links between media use and depression as described above, we further hypothesized that exposure to television is more potent than exposure to videocassettes, computer games, or radio. Because of the known preponderance of media images of girls and women with unattainably thin and unblemished bodies,52,53 we also hypothesized that the relationship between television exposure and depression is stronger in young women than in young men.

METHODS

SAMPLE

We analyzed the public-use data set from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents conducted from September 1, 1994, to April 30, 2002. Wave 1 data, collected in 1995, included 6504 participants in grades 7 through 12 who were randomly selected from a larger nationally representative sample to be interviewed in their homes. Of those with valid wave 1 data, 4882 participants (75.1%) were reinterviewed in their homes 7 years later (wave 3).

We excluded participants who did not have complete depression data at baseline (n=18) or at follow-up (n=25). Because we were interested in identifying incident development of depression during the study period, we also excluded those who were depressed at time 1 (n=697). Our final study sample consisted of 4142 individuals who did not report depression symptoms above threshold at baseline and who had complete depression data at baseline and follow-up. This represented 63.7% of the 6504 individuals interviewed at baseline.

MEASURES

Depression

The Centers for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) consists of 20 items that have been successfully used for screening and quantifying the severity of depression in general populations, and shorter versions are commonly used.54,55 Nine CES-D items were included in baseline (wave 1) and 7-year (wave 3) assessments in the Add Health study. We formed our depression scale using all 9 items. These items asked respondents how often in the last 7 days they had experienced specific depressive symptoms (Table 1). Each item was scored on a scale of 0 to 3, corresponding to responses of “never or rarely,” “sometimes,” “a lot of the time,” and “most or all of the time.” We summed these responses to form depression scores at each time point ranging from 0 (no symptoms of depression) to 27 (severe symptoms of depression). The 9-item depression scale was internally consistent at baseline (Cronbach α=.79) and follow-up (Cronbach α=.81).

Table 1.

Nine-Item Centers for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scalea

| Item | Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | You were bothered by things that don't usually bother you |

| 2 | You felt that you could not shake off the blues, even with help from your family and your friends |

| 3 | You felt that you were just as good as other people |

| 4 | You had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing |

| 5 | You felt depressed |

| 6 | You felt that you were too tired to do things |

| 7 | You enjoyed life |

| 8 | You felt sad |

| 9 | You felt that people disliked you |

Among adolescents, the complete 20-item CES-D scale (range, 0-60) has strong predictive validity for depression at a threshold score of 24 for female adolescents and 22 for male adolescents.55 We scaled our cutoff scores on the basis of the number of items in our scale, resulting in depression cutoff scores of 11 or higher for female adolescents and 10 or higher for male adolescents (scale range, 0-27). Others have used similar methods to define a threshold for depression when using Add Health data.56,57

Media Exposure

At the Add Health baseline evaluation (wave 1), information was collected about media exposure in 1995. Participants were asked to report hours of exposure during the last week to each of 4 types of electronic media: television, videocassettes (DVDs were not widely introduced until 1997), computer games, and radio. We analyzed exposure to each media type as a continuous variable in hours per day. We also created a summary measure of media exposure equal to the sum of the hours per day of exposure to each of the 4 media types.

Sociodemographic Covariates

The Add Health survey assessed relevant sociodemographic covariates known to be related to depression and/or media exposure. Sex was self-reported. Age at follow-up was computed on the basis of the participant's date of birth and date of in-home survey. Race was self-reported as any combination of white, African American, Asian, American Indian, and other. Ethnicity was self-reported as Hispanic or not Hispanic. As a proxy for socioeconomic status, we used maternal educational level (did not graduate from high school, graduated from high school or received a general equivalency diploma, had further education after high school but did not graduate from college, graduated from college but did not pursue further education, or had an advanced or other degree). The survey also included the participants' marital status and highest level of educational attainment at follow-up.

Methods of Analysis

To compare demographic and media use variables between participants who did or did not exhibit depressive symptoms at follow-up, we used t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We used P<.05 (2-tailed) to define statistical significance for all analyses. We conducted these analyses using wave 3 sampling weights.

We then used multiple logistic regression to assess the independent association between each media exposure at baseline and presence of depression at follow-up. We applied sampling weights for wave 3 of the Add Health study in all of our regression models. In addition to excluding all participants who were depressed at time 1, we controlled for baseline CES-D score in all analyses. We searched for interaction terms between media use variables and sex because media use is strikingly different between male and female users8 and because representation of male and female individuals in media are different.52 Participants with missing data were not included in our analyses. This did not affect our results because less than 2% of wave 3 participants had missing data for this analysis.

Our primary models included all measured covariates. To test the robustness of our results, we conducted all analyses using stepwise backward logistic regression with criteria for removal from the model of P<.15.

RESULTS

SAMPLE

Of the 4142 participants who did not meet criteria for depression at baseline and had complete depression data for baseline and follow-up, 308 (7.4%) met symptom criteria for depression at follow-up. Of all participants, 52.5% were female; 23.7% were African American, and 10.3% were Hispanic; and their mean (SD) age at follow-up was 21.8 (1.8) years. Most participants (84.6%) had achieved at least a high school diploma, and 17.4% had been married (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Study Populationa

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total Sample (N=4142) | Those Who Did Not Develop Depressive Symptoms (n=3834) | Those Who Developed Depressive Symptoms by Follow-up (n=308) | P Valueb |

| Media use, mean (SD), h/d | ||||

| Television | 2.30 (2.14) | 2.28 (2.12) | 2.64 (2.51) | .004 |

| Videocassettes | 0.62 (0.96) | 0.62 (0.95) | 0.65 (1.08) | .38 |

| Computer games | 0.41 (0.94) | 0.41 (0.93) | 0.45 (0.99) | .44 |

| Radio | 2.34 (2.79) | 2.35 (2.80) | 2.24 (2.63) | .82 |

| Total | 5.67 (4.46) | 5.66 (4.46) | 5.98 (4.46) | .04 |

| Demographic characteristic | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 21.8 (1.82) | 21.8 (1.82) | 21.5 (1.76) | .02 |

| Female sex | 2173 (52.5) | 1990 (51.9) | 183 (59.4) | .03 |

| Racec/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2809 (67.8) | 2622 (68.4) | 187 (60.7) | .005 |

| African American | 983 (23.7) | 891 (23.2) | 92 (29.9) | .08 |

| Asian | 161 (3.9) | 151 (3.9) | 10 (3.3) | .35 |

| American Indian | 155 (3.7) | 136 (3.6) | 19 (6.2) | .11 |

| Other | 248 (6.0) | 227 (5.9) | 21 (6.8) | .16 |

| Hispanic | 428 (10.3) | 388 (10.1) | 40 (13.0) | .05 |

| SESd | ||||

| 1 | 633 (16.1) | 569 (15.6) | 64 (22.4) | <.001 |

| 2 | 2066 (52.6) | 1907 (52.4) | 159 (55.6) | |

| 3 | 1229 (31.3) | 1166 (32.1) | 63 (22.0) | |

| Ever married | 720 (17.4) | 674 (17.6) | 46 (15.0) | .17 |

| Educational achievement of at least graduation from high school | 3501 (84.7) | 3274 (85.5) | 227 (74.2) | <.001 |

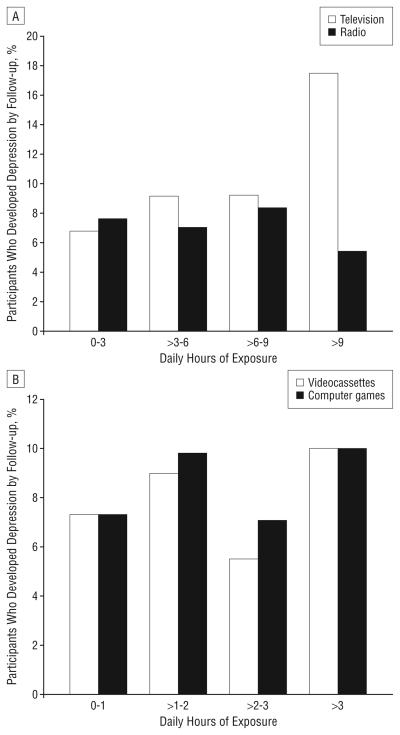

MEDIA USE

Baseline mean (SD) daily media use was 5.68 (4.46) hours, consisting of 2.30 (2.14) hours of television, 0.62 (0.96) hours of videocassettes, 0.41 (0.94) hours of computer games, and 2.34 (2.79) hours of radio (Table 2). Those who were depressed at follow-up had watched more television at baseline (2.64 vs 2.28 h/d) (Table 2 and Figure 2A) but had not been exposed to more video-cassettes, computer games, or radio (Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Percentage of sample with depression at follow-up. Only those participants who were not depressed at baseline (n=4142) were included. Television and radio (A) and videocassettes and computer games (B) were compared because adolescents are exposed to these for similar amounts of time daily (see Table 2).

MULTIVARIABLE ASSOCIATION OF MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION

In the fully adjusted models, participants had significantly greater odds of developing depression by follow-up for each hour of daily television viewed (odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 1.08 [1.01-1.16]) (Table 3). In addition, those reporting higher total media exposure had significantly greater odds of developing depression (1.05[1.0004-1.10]) for each additional hour of daily use. Hours of exposure to videocassettes, computer games, and radio were not independently associated with high levels of depressive symptoms at follow-up. All levels of significance for all analyses were similar when analyses were conducted using stepwise backward regression with criteria for removal of _P_>.15.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Developing Depressiona

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Television | Videocassettes | Video Games | Radio | Total Mediab |

| Each hour of use, eg, television or videocassettes | 1.08 (1.01-1.16)c | 1.03 (0.86-1.25) | 1.04 (0.89-1.22) | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | 1.05 (1.0004-1.10)c |

| Baseline CES-D score, each point | 1.30 (1.23-1.38)c | 1.30 (1.23-1.38)c | 1.30 (1.23-1.38)c | 1.30 (1.23-1.38)c | 1.31 (1.23-1.38)c |

| Age | 0.88 (0.81-0.97)c | 0.87 (0.80-0.96)c | 0.88 (0.80-0.96)c | 0.87 (0.80-0.95)c | 0.87 (0.79-0.95)c |

| Female sex | 1.10 (0.82-1.48) | 1.07 (0.80-1.44) | 1.09 (0.81-1.47) | 1.09 (0.80-1.47) | 1.62 (1.01-2.60)c |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 0.52 (0.19-1.45) | 0.53 (0.19-1.45) | 0.53 (0.20-1.41) | 0.53 (0.19-1.48) | 0.53 (0.19-1.45) |

| African American | 0.62 (0.21-1.78) | 0.65 (0.23-1.86) | 0.66 (0.24-1.82) | 0.63 (0.22-1.82) | 0.63 (0.22-1.79) |

| Asian | 0.28 (0.83-0.93)c | 0.28 (0.08-0.93)c | 0.28 (0.09-0.91)c | 0.28 (0.08-0.93)c | 0.29 (0.09-0.96)c |

| American Indian | 1.31 (0.63-2.72) | 1.36 (0.66-2.80) | 1.33 (0.67-2.66) | 1.37 (0.67-2.84) | 1.26 (0.62-2.59) |

| Other | 0.65 (0.24-1.78) | 0.69 (0.26-1.85) | 0.69 (0.26-1.83) | 0.69 (0.25-1.88) | 0.68 (0.25-1.86) |

| Hispanic | 1.04 (0.62-1.74) | 1.03 (0.61-1.74) | 1.04 (0.62-1.73) | 1.03 (0.61-1.75) | 1.03 (0.61-1.73) |

| SESd | |||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | 0.83 (0.55-1.25) | 0.84 (0.56-1.26) | 0.84 (0.56-1.27) | 0.85 (0.56-1.28) | 0.82 (0.54-1.24) |

| 3 | 0.63 (0.38-1.03) | 0.62 (0.38-1.01) | 0.62 (0.38-1.01) | 0.60 (0.37-0.99)c | 0.59 (0.36-0.96)c |

| Ever married | 0.73 (0.46-1.16) | 0.73 (0.47-1.16) | 0.73 (0.47-1.16) | 0.75 (0.47-1.19) | 0.73 (0.46-1.15) |

| Educational achievement of at least graduation from high school | 0.58 (0.40-0.83)c | 0.57 (0.40-0.82)c | 0.57 (0.40-0.82)c | 0.57 (0.39-0.82)c | 0.59 (0.41-0.86)c |

INTERACTIONS BY SEX

Interaction terms between sex and use of television (odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 0.97 [0.85-1.10]), videocassettes (0.86 [0.63-1.16]), and computer games (0.79 [0.53-1.19]) were nonsignificant. However, the interactions between sex and radio use (0.90 [0.81-0.9999) and total media exposure (0.93 [0.88-0.10]) were statistically significant. Because of the coding of the sex variable, these values indicate that, in each case, given the same media exposures, there was a tendency for young women to have lower odds of developing depression compared with young men.

COMMENT

This study demonstrates that, in a nationally representative sample of adolescents, television and overall media exposure are associated with the development of depressive symptoms in young adulthood, especially in young men. These results held despite controlling with multiple covariates, including baseline CES-D score. Exposure to videocassettes, video games, and radio were not associated with development of depression. The association of certain media exposures in this study with the subsequent presence of depressive symptoms is consistent with the findings of others who have associated media exposure with other mental health conditions.18,58

Of the various media exposures measured in the Add Health study, we found television and overall media exposure to be most closely linked to depression. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that excessive media exposure may detract from protective experiences or lead to poor sleep. Among the 4 media exposures measured, television viewing is unique in that it consumes a large amount of time,8 and participants who had the highest levels of baseline television exposure were most likely to develop depression (Figure 2A). Although radio exposure is also large, it more commonly is present in the background and frequently accompanies other activities.8

However, the finding that television was the medium most strongly associated with the development of depression in young adulthood is also consistent with the hypothesis that the specific content of certain media may lead to depression. For example, television contains more advertising than either videocassettes or computer games, and advertisements are often designed to make the viewer believe that he or she requires a certain product or lifestyle to feel adequate.59 Although radio also contains advertising, the combined visual and aural experience of television may be more effective and compelling.60

Another difference between videocassettes and television is that content on videocassettes is generally specifically chosen by the viewer, whereas television is more likely to be provided by default (ie, channel surfing).31 Television also contains the most compelling and dramatic news reports, many of which are anxiogenic,49,50 and repeated exposure to these messages may lead not only to anxiety but also to depression.3,16 Television also seems to contain the most stereotyping among media messages.25,26,61,62

In general, television is no more likely than other media such as movies or music to contain risk-taking behavior.33,35,36 Thus, our results suggest that the mechanism by which media exposure may influence development of depression is related to a combination of factors including displacement of protective experiences, poor sleep, self-comparison with unattainable images, stereotyping, and anxiety-provoking content.

Although we did not find that overall exposure to any of these types of media was associated with less depression, this does not rule out the hypothesis that certain humorous or life-affirming media exposures may reduce the likelihood of depression.41,42 Because we were not able to differentiate specific exposures, certain exposures still may be beneficial to some. However, it is noteworthy that this study shows that total television and total media exposure are associated with an increase, not a reduction, in depression.

It was an interesting and unexpected finding that young women did not exhibit a stronger association between media exposure and development of depression. Indeed, they had significantly lower odds of developing depression in the model involving total media exposure. Men and women use different coping mechanisms when dealing with depression; women are more likely to internalize and ruminate about their condition, whereas men are more likely to engage in externalizing or distracting activities.63,64 Similarly, adolescent girls may develop closer and more intimate social ties than their male counterparts, giving them more social reserve than adolescent boys.63,64 Thus, whereas adolescent girls may be more likely to seek comfort from peers, parents, or professionals, adolescent boys may use distractions such as television and other media to cope with underlying subsyndromal depression until different stressors and demands emerge later in life, leading to more substantial symptoms of depression. Thus, excessive time devoted to media may affect male users more substantially.4,22,65,66

It is also possible that actual media content may have more of a detrimental effect on male psychologic development than has been previously appreciated. The dominant fiction of idealized masculinity and sex roles to which boys are exposed while watching television may reinforce feelings of marginalization and worthlessness.22,67,68 The depressogenic media exposure in combination with preexisting negative cognitions may make unpopular or rejected boys feel even more outcast. Future research may explore questions such as these by examining moderating effects of other factors such as strength of interpersonal relationships on the link between media use and depression.

These findings have implications for clinicians working in a variety of fields. Psychiatrists, pediatricians, family physicians, internists, and other health care providers who work with adolescents may find it useful to ask their patients about television and other media exposure. When high amounts of television or total exposure are present, a broader assessment of the adolescent's psychosocial functioning may be appropriate, including screening for current depressive symptoms and for the presence of additional risk factors. If no other immediate intervention is indicated, encouraging patients to participate in activities that promote a sense of mastery and social connection may promote the development of protective factors against depression.

Helping children at risk of depression to bolster social support and involvement in activities is routine for child psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who work with adolescents; however, these clinicians may also want to consider an assessment of television exposure as a marker of vulnerability to the development of depressive symptoms. Further research will be necessary to understand how television exposure may correlate with the development of depressive symptoms in psychiatric clinical populations or with the clinical course of diagnosed depression. At the population level, as our understanding of the links between the mass media and adolescent depression become further refined, prevention programs may wish to incorporate these research findings into educational efforts aimed at adolescents and their families.

Our study was limited in that we relied on self-report of media exposure. Although self-report of media habits is subject to recall bias, it is currently standard practice in research of this type when it is not feasible to use recognition measures.37,69,70 It should also be noted that our independent variables were based on a single point estimate of media exposure, and there is no assurance that this remained stable over time. It is also disappointing that the baseline survey did not assess Internet exposure; however, this is a known limitation of the Add Health survey.

Insofar as the dependent variable, the Add Health study included only 9 items from the CES-D at follow-up, preventing us from using the complete 20-item scale. However, Add Health personnel carefully selected these particular 9 items because of their excellent face validity for adolescents and based on psychometric testing that showed that they represented the vast majority of the variance in the complete 20-item scale. Another limitation of the CES-D in general is its lack of specificity; for example, it tends to detect anxiety and depression.

It should be emphasized that, although our study showed a longitudinal association between media exposure in adolescence and development of depressive symptoms at later follow-up, this association does not necessarily imply causality. For example, it may be that adolescents with preexisting vulnerability to later developing depression are differentially attracted to watching television, perhaps owing to behavioral inhibition or aversive interpersonal and family relationships.

In conclusion, the present study breaks new ground in linking media use in adolescence to the development of depressive symptoms in young adulthood, especially relative to television exposure and overall media use. The study also highlights a previously unappreciated potential vulnerability to media exposure in male adolescents in particular. Its longitudinal design and large nationally representative sample are important strengths. Despite this study's limitations, these findings suggest important directions for future research and interventions with the goal of reducing the massive toll of depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Career Development Award K07-CA114315 from the National Cancer Institute, a Physician Faculty Scholar Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and a grant from the Maurice Falk Foundation (all to Dr Primack).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission on Adolescent Depression and Bipolar Disorder . Depression and bipolar disorder. In: Evans DL, Foa EB, Gur RE, et al., editors. Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders: What We Know and What We Don't Know: A Research Agenda for Improving the Mental Health of Our Youth. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paradis AD, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Fitzmaurice G. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: the impact of active and past depression on young adult functioning. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(5):318–323. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000217807.56978.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AM, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: risks and impairments. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(3):500–510. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohnert AM, Garber J. Prospective relations between organized activity participation and psychopathology during adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(6):1021–1033. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Pulkki L, Puttonen S, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. The longitudinal effects of social support and hostility on depressive tendencies. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(5):1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rideout V, Roberts D, Foehr U. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year-olds. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHale SM, Crouter AC, Tucker CJ. Free-time activities in middle childhood: links with adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2001;72(6):1764–1778. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):e119–e131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/112/2/e119. Accessed November 11, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggermont S, Van den Bulck J. Nodding off or switching off? the use of popular media as a sleep aid in secondary-school children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(7-8):428–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owens J, Maxim R, McGuinn M, Nobile C, Msall M, Alario A. Television-viewing habits and sleep disturbance in school children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(3):e27. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.3.e27. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/112/2/e119. Accessed November 11, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van den Bulck J. Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children. Sleep. 2004;27(1):101–104. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Bulck J. Adolescent use of mobile phones for calling and for sending text messages after lights out: results from a prospective cohort study with a one-year follow-up. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1220–1223. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Associations between content types of early media exposure and subsequent attentional problems. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):986–992. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakdawalla Z, Hankin BL, Mermelstein R. Cognitive theories of depression in children and adolescents: a conceptual and quantitative review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2007;10(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker AE, Burwell RA, Gilman SE, Herzog DB, Hamburg P. Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:509–514. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ. Violent television viewing during preschool is associated with antisocial behavior during school age. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):993–999. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(7):765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bissell K, Zhou P. Must-See TV or ESPN: entertainment and sports media exposure and body-image distortion in college women. J Commun. 2004;54(1):5–21. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02610.x. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van den Bulck J. Is television bad for your health? behavior and body image of the adolescent “couch potato”. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(3):273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latner JD, Rosewall JK, Simmonds MB. Childhood obesity stigma: association with television, videogame, and magazine exposure. Body Image. 2007;4(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rich M, Woods ER, Goodman E, Emans SJ, DuRant RH. Aggressors or victims: gender and race in music video violence. Pediatrics. 1998;101(4, pt 1):669–674. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Signorielli N. Children, television, and gender roles: messages and impact. J Adolesc Health Care. 1990;11(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(90)90129-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright JC, Huston AC, Truglio R, Fitch M, Smith E, Piemyat S. Occupational portrayals on television: children's role schemata, career aspirations, and perceptions of reality. Child Dev. 1995;66(6):1706–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raley AB, Lucas JL. Stereotype or success? prime-time television's portrayals of gay male, lesbian, and bisexual characters. J Homosex. 2006;51(2):19–38. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. WW Norton Co Inc; New York, NY: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison K, Cantor J. Tales from the screen: enduring fright reactions to scary media. Media Psychol. 1999;1(2):97–116. doi:10.1207/s1532785xmep0102_1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strasburger VC, Wilson BJ, Jordan A. Children, Adolescents, and the Media. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubey RW, Csikszentmihalyi M. Television and the Quality of Life: How Viewing Shapes Everyday Experience. L Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escobar-Chaves SL, Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Low BJ, Eitel P, Thickstun P. Impact of the media on adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):303–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV, Agarwal AA, Fine MJ. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):169–175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Primack BA, Gold MA, Schwarz EB, Dalton MA. Degrading and non-degrading sex in popular music: a content analysis. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(5):593–600. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts DF, Christenson PG, Henriksen L, Brandy E. Substance Use in Popular Music Videos. Office of National Drug Control Policy; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts DF, Henriksen L, Christenson PG. Substance Use in Popular Movies and Music. Office of National Drug Control Policy; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson TN, Chen HL, Killen JD. Television and music video exposure and risk of adolescent alcohol use. Pediatrics. 1998;102(5):E54. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.e54. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/102/5/e54. Accessed November 11, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eshbaugh EM, Gute G. Hookups and sexual regret among college women. J Soc Psychol. 2008;148(1):77–89. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.1.77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fong GT, Hammond D, Laux FL, et al. The near-universal experience of regret among smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 3):S341–S351. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oswalt SB, Cameron KA, Koob JJ. Sexual regret in college students. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34(6):663–669. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-7920-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacDonald CM. A chuckle a day keeps the doctor away: therapeutic humor and laughter. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2004;42(3):18–25. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20040315-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wooten P. Humor: an antidote for stress. Holist Nurs Pract. 1996;10(2):49–56. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christenson PG, Henriksen L, Roberts DF. Substance Use in Popular Prime Time Television. Office of National Drug Control Policy; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher DA, Hill DL, Grube JW, Gruber EL. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual content on television: a quantitative analysis across two seasons. J Homosex. 2007;52(3-4):167–188. doi: 10.1300/J082v52n03_08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haninger K, Ryan MS, Thompson KM. Violence in teen-rated video games [published online March 12, 2004] MedGenMed. 2004;6(1):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett MP, Zeller JM, Rosenberg L, McCann J. The effect of mirthful laughter on stress and natural killer cell activity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(2):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richman J. The lifesaving function of humor with the depressed and suicidal elderly. Gerontologist. 1995;35(2):271–273. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saper B. The therapeutic use of humor for psychiatric disturbances of adolescents and adults. Psychiatr Q. 1990;61(4):261–272. doi: 10.1007/BF01064866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahern J, Galea S, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Television images and probable post-traumatic stress disorder after September 11: the role of background characteristics, event exposures, and perievent panic. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000116465.99830.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, Brandt ENJ, Pfefferbaum RL, Doughty DE, Rainwater SM. Media exposure in children one hundred miles from a terrorist bombing. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1023293824492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campbell AJ, Cumming SR, Hughes I. Internet use by the socially fearful: addiction or therapy? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9(1):69–81. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Field AE, Cheung L, Wolf AM, Herzog DB, Gortmaker SL, Colditz GA. Exposure to the mass media and weight concerns among girls. Pediatrics. 1999;103(3):E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.e36. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/103/3/e36. Accessed November 11, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Becker AE. Television, disordered eating, and young women in Fiji: negotiating body image and identity during rapid social change. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2004;28(4):533–559. doi: 10.1007/s11013-004-1067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen YL, Russell ST, Driscoll AK. Measurement equivalence of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: a national study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(1):47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Screening for adolescent depression: a comparison of depression scales. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(1):58–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):497–504. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shrier LA, Harris SK, Sternberg M, Beardslee WR. Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):179–189. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Black D, Newman M. Television violence and children. BMJ. 1995;310(6975):273–274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6975.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisend M, Moller J. The influence of TV viewing on consumers' body images and related consumption behavior. Marketing Lett. 2007;18(1-2):101–116. doi:10.1007/s11002-006-9004-8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Druckman JN. The power of television images: the first Kennedy-Nixon debate revisited. J Polit. 2003;65:559–571. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenberg BS, Eastin M, Hofschire L, Lachlan K, Brownell KD. Portrayals of over-weight and obese individuals on commercial television. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1342–1348. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson T, Callister M, Jankoski T. Portrayal of body weight on children's television sitcoms: a content analysis. Body Image. 2008;5(2):141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex differences in unipolar depression: evidence and theory. Psychol Bull. 1987;101(2):259–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Renk K, Creasey G. The relationship of gender, gender identity, and coping strategies in late adolescents. J Adolesc. 2003;26(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hay IAA. The development of adolescents' emotional stability and general self-concept: the interplay of parents, peers, and gender. Int J Disability Dev Educ. 2003;50(1):77–91. doi:10.1080/1034912032000053359. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Postman N, Nystrom C, Strate L, Weingartner C. Myths, Men, and Beer: An Analysis of Beer Commercials on Broadcast Television. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gurian M. The Good Son: Shaping the Moral Development of Our Boys and Young Men. GP Putnam's Sons; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carson NJ, Rodriguez D, Audrain-McGovern J. Investigation of mechanisms linking media exposure to smoking in high school students. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown JD, L'Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television and magazines predicts black and white adolescents' sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]