Complete genome sequence of Pedobacter heparinus type strain (HIM 762-3T) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Pedobacter heparinus (Payza and Korn 1956) Steyn et al. 1998 comb. nov. is the type species of the rapidly growing genus Pedobacter within the family Sphingobacteriaceae of the phylum ‘Bacteroidetes’. P. heparinus is of interest, because it was the first isolated strain shown to grow with heparin as sole carbon and nitrogen source and because it produces several enzymes involved in the degradation of mucopolysaccharides. All available data about this species are based on a sole strain that was isolated from dry soil. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence, and annotation. This is the first report on a complete genome sequence of a member of the genus Pedobacter, and the 5,167,383 bp long single replicon genome with its 4287 protein-coding and 54 RNA genes is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: mesophile, strictly aerobic, dry soil, Gram-negative, flexible rods, heparinase producer, Sphingobacteriaceae

Introduction

Pedobacter heparinus strain HIM 762-3 (DSM 2366 = ATCC 13125 = JCM 7457 and other culture collections) is the type strain of the species, and was first described in 1956 by Payza and Korn as Flavobacterium heparinum (basonym) [1]. The authors of the original species description provided no type strain designation when depositing their isolate in the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 13125T). In the Approved Lists of Bacterial Names (1980) the type strain of F heparinum appears as ATCC 13125T. Strain HIM 762-3T was deposited in the DSMZ culture collection by Walter Mannheim (Marburg) in 1982, and ATCC is using the same strain designation for their ATCC 13125T. Following successive transfers of this species to the genera Cytophaga [2] and Sphingobacterium [3] the present name P. heparinus was proposed by Steyn et al. in 1998 [4]. Enzymes produced by P. heparinus could be successfully used for the study of the structure of heparin and chondroitin, important animal mucopolysaccharides with sulfate groups. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for P. heparinus HIM 762-3T (Table 1), together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Table 1. Classification and general features of P. heparinus HIM 762-3T based on MIGS recommendations [5].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidencecode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | ||

| Phylum Bacteroidetes | |||

| Class Sphingobacteria | TAS [6] | ||

| Order Sphingobacteriales | TAS [6] | ||

| Family Sphingobacteriaceae | TAS [4] | ||

| Genus Pedobacter | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Pedobacter heparinus | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain HIM 762-3 | |||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [4] | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped | TAS [4] | |

| Motility | probably gliding, non-flagellated | TAS [4] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [4] | |

| Temperature range | mesophile, 10-35°C | TAS [2] | |

| Optimum temperature | 25-30°C for growth | TAS [2] | |

| Salinity | 0-3% NaCl | TAS [2] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobe | TAS [1,2] |

| Carbon source | carbohydrates, glycosaminoglycans | TAS [1,4] | |

| Energy source | chemoorganotroph | TAS [1,2,4] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | soil | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [7] | |

| Isolation | not reported | ||

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | not reported | |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | before 1956 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 | Latitude – Longitude | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Classification and features

Until now the species P. heparinus has comprised only one strain, HIM 762-3T. Two closely related strains, Gsoil 042T and LMG 10353T, were recently described and affiliated to the species P. panaciterrae [9] and P. africanus [4], respectively, based on low DNA-DNA binding values to the type strain of P. heparinus. Unclassified strains with significant (98%) 16S rRNA sequence similarity to these species were observed from Ginseng field soil (AM279216), dune grassland soil [10] and activated sludge samples [11]. Environmental genomic surveys indicated highly similar (96% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity) phylotypes in BAC libraries generated from Brassica rapa subsp_. pekinensis_ (field mustard) and Sorghum bicolor (milo) (ED512136, DX082358, BZ779630). A draft genome sequence of the unclassified Pedobacter strain BAL39 isolated from the Baltic Sea was recently determined by the J. Craig Venter Institute (Genbank NZ_ABCM00000000).

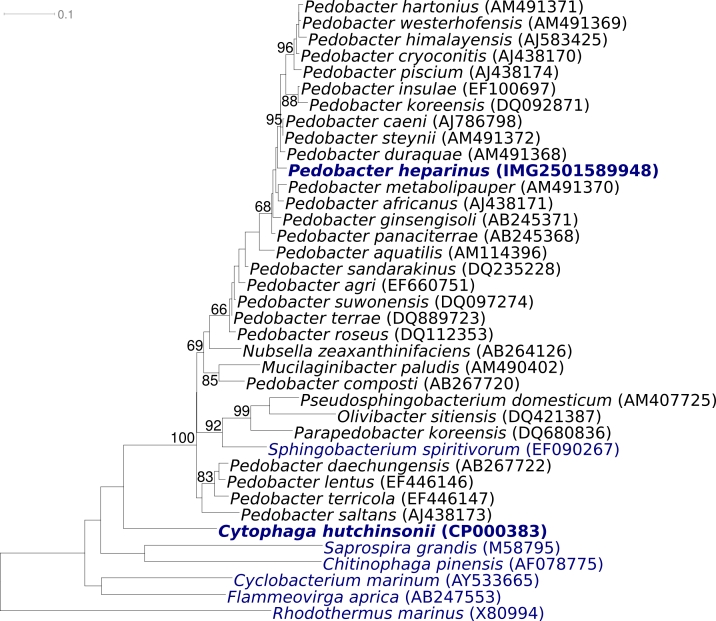

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of P. heparinus strain HIM 762-3T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the three 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome are identical and differ by only one nucleotide from the previously published 16S rRNA gene sequence derived from DSM 2366 (AJ438172).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of P. heparinus strain HIM 762-3T and the type strains of the genus Pedobacter, as well as all type strains of the other genera within the family Sphingobacteriaceae, inferred from 1373 aligned characters [12,13] of the 16S rRNA gene under the maximum likelihood criterion [14]. The tree was rooted with the type strains of the other families within the order ‘Sphingobacteriales’. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [15] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

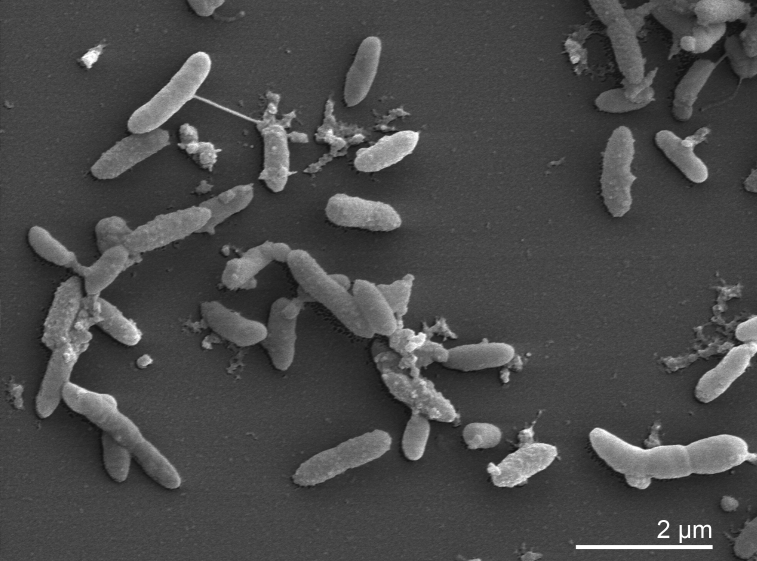

P. heparinus cells are Gram-negative, non-flagellated, non-spore-forming, flexible rods with rounded or slightly tapered ends. Cell width is 0.4-0.5 µm and cell length can vary from 0.7 to 6 µm. Protrusions can be observed on the cell surface (Figure 2). Some authors have reported a gliding motility [2]. Colonies are 1–4 mm in diameter and produce a yellowish, water insoluble, non-fluorescent pigment upon growth on nutrient agar [4]. Growth occurs at 10 and 35°C, but not above 37°C. The optimal temperature for growth is between 25 and 30°C [2]. The pH range for growth is 7-10 [2]. Strain HIM 762-3T is strictly aerobic and prefers carbohydrates and sugars as carbon sources. Neither nitrate nor nitrite is reduced. The strain is catalase and oxidase positive. Acetoin is produced from pyruvate, but indole is not produced from tryptophan. HIM 762-3T is negative for gelatinase, urease and DNase, but esculin and Tween 20–80 are hydrolyzed; acid and alkaline phosphatases are present [4]. The strain does not require vitamins, but L-histidine is essential for growth [16]. A special feature of strain HIM 762-3T is its ability to degrade acidic sulfated mucoheteropolysaccharides, like heparin and chondroitin that are formed in various animal tissues. Enzymes involved in the degradation of heparin are only produced after induction by the substrate and are formed intracellularly [16]. Several different types of enzymes are involved in the complete degradation of heparin, including heparinases, glycuronidase, sulfoesterases and sulfamidases [17]. The first step in the degradation of heparin is catalyzed by heparinase (EC 4.2.2.7), an α1-4-eliminase which acts specifically on the glycosidic linkage between _N_-sulfated D-glucosamine and sulfated D-glucuronic acid (or L-iduronic acid). The use of heparinase in the elucidation of the structure of heparin, blood deheparinization or enzymatic assay of heparin have been proposed [16]. The genetics of heparin and chondrotitin degradation in P. heparinus was studied extensively and a high-level expression system for glycosaminoglycan lyases in this species has been developed [18]. Three different genes encoding heparinases (_hepA_-C) and two different genes for chondroitinases (cslA and cslB) could be characterized [18]. The crystal structures of the chondroitinase B [19] and heparinase II [20] of P. heparinus were resolved at high resolution.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of P. heparinus HIM 762-3T

Chemotaxonomy

The peptidoglycan structure of strain HIM 762-3T is still unknown. The cellular fatty acid pattern is dominated by saturated, iso branched and hydroxylated acids. The most abundant non-polar cellular fatty acids are iso_-15:0, 16:1 ω7_c, _iso_-17:0 (3-OH), and _iso_-15:0 (2-OH) [4]. Large amounts of long-chain bases are formed, one of which has been identified as dihydrosphingosin [3]. Strain HIM 762-3T contains menaquinone MK-7.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of each phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [15] and the complete genome sequence in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two genomic Sanger libraries - 8 kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 7.5x Sanger |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| INSDC / Genbank ID | CP001681 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | July 31, 2009 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01041 | |

| NCBI project ID | 27949 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501533212 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 2366 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

P. heparinus strain HIM 762-3T, DSM 2366, was grown in DSMZ medium 1 (Nutrient Brot) at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 1-1.5 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with a modified protocol for cell lysis, adding additonal 100 µl lsozyme; 500 µl chromopeptidase, lysostaphin, mutanolysin, each, to the standard lysis solution, but reducing proteinase K to 160µl, only. Lysis solution was incubated overnight at 35°C on a shaker.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using Sanger sequencing platform only. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the DOE JGI can be found on their website. The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment. After the shotgun, stage reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Soft ware, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher [21] or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). A total of 1,897 finishing reactions were produced to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The completed genome sequences of P. heparinus contains 45,821 Sanger reads, achieving an average of 7.5 x sequence coverage per base with an error rate less than 1 in 100,000.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [22] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG-ER) platform [23].

Genome properties

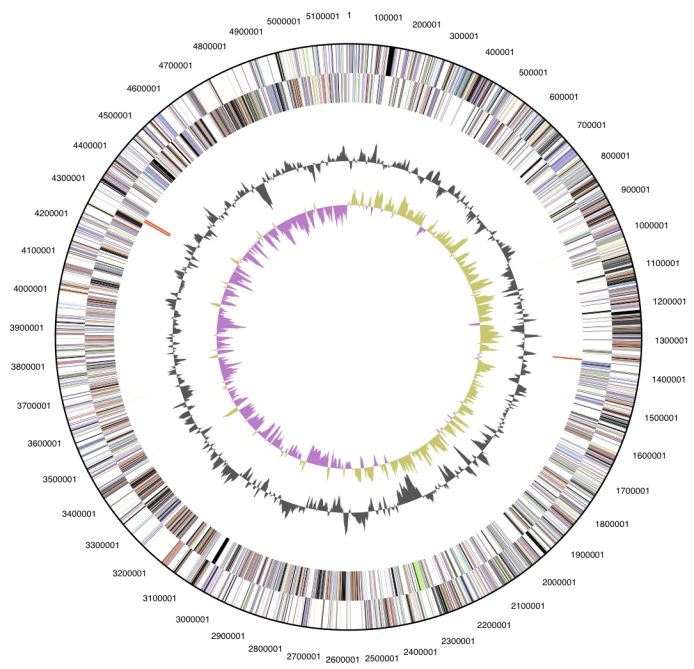

The genome is 5,167,383 bp long and comprises one main circular chromosome with a 42.1% GC content (Table 3, Figure 3). Of the 4,341 genes predicted, 4,287 were protein coding genes, and 54 RNAs. Thirty-five pseudogenes were also identified. A minority of the genes (38.1%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,167,383 | 100.00% |

| DNA Coding region (bp) | 4,829,823 | 93.47% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 2,172,827 | 42.05% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 4341 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 54 | 1.22% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 4287 | 98.69% |

| Pseudo genes | 35 | 0.81% |

| Genes with function prediction | 2911 | 67.05% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 899 | 20.70% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2806 | 64.59% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2991 | 68.85% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1425 | 32.80% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1051 | 24.19% |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0.00% |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the genome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 21 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 154 | 3.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0.0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 281 | 6.5 | Transcription |

| L | 113 | 2.6 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 19 | 0.4 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 59 | 1.4 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 222 | 5.2 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 265 | 6.1 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 13 | 0.3 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 48 | 1.1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 116 | 2.7 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 140 | 3.3 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 292 | 6.7 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 209 | 4.9 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 65 | 1.5 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 136 | 3.1 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 104 | 2.4 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 234 | 5.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 58 | 1.3 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 373 | 8.7 | General function prediction only |

| S | 229 | 5.3 | Function unknown |

| - | 1481 | 34.5 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Maren Schröder for growing P. heparinus cultures and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ) This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1.

References

- 1.Korn ED, Payza AN. The degradation of heparin by bacterial enzymes. I. Adaptation and lyophilized cells. J Biol Chem 1956; 223:853-858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen P. Description and taxonomic status of Cytophaga heparina (Payza and Korn) comb. nov. (basionym: Flavobacterium heparinum Payza and Korn 1956). Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:473-475 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeuchi M, Yokota A. Proposals of Sphingobacterium faecium sp. nov., Sphingobacterium piscium sp. nov., Sphingobacterium heparinum comb. nov., Sphingobacterium thalpophilum comb. nov. and two genospecies of the genus Sphingobacterium, and synonymy of Flavobacterium yabuuchiae and Sphingobacterium spiritivorum. J Gen Appl Microbiol 1992; 38:465-482 10.2323/jgam.38.465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steyn PL, Segers P, Vancanneyt M, Sandra P, Kersters K, Joubert JJ. Classification of heparinolytic bacteria into a new genus, Pedobacter, comprising four species: Pedobacter heparinus comb. nov., Pedobacter piscium comb. nov., Pedobacter africanus sp. nov. and Pedobacter saltans sp. nov. proposal of the family Sphingobacteriaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:165-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrity GM, Lilburn TG, Cole JR, Harrison SH, Euzéby J, Tindall BJ. The Taxonomic Outline of the Bacteria and Archaea (TOBA 7.7). 2007 www.taxonomicoutline.org

- 7.Biological Agents. Technical rules for biological agents www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 8.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon MH, Ten LN, Im WT, Lee ST. Pedobacter panaciterrae sp. nov., isolated from soil in South Korea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007; 57:381-386 10.1099/ijs.0.64693-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Boer W, Wagenaar AM, Klein Gunnewiek PJ, van Veen JA. In vitro suppression of fungi caused by combinations of apparently non-antagonistic soil bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2007; 59:177-185 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrero-Colón M, Nakatsu CH, Konopka A. Effect of nutrient periodicity on microbial community dynamics. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:3175-3183 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3175-3183.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web-servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:D475-D479 10.1093/nar/gkm884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galliher PM, Cooney CL, Langer R, Linhardt RJ. Heparinase production by Flavobacterium heparinum. Appl Environ Microbiol 1981; 41:360-365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietrich CP, Silva ME, Michelacci YM. Sequential degradation of heparin in Flavobacterium heparinum. Purification and properties of five enzymes involved in heparin degradation. J Biol Chem 1973; 248:6408-6415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blain F, Tkalec AL, Shao Z, Poulin C, Pedneault M, Gu K, Eggimann B, Zimmermann J, Su H. Expression system for high levels of GAG lyase gene expression and study of the hepA upstream region in Flavobacterium heparinum. J Bacteriol 2002; 184:3242-3252 10.1128/JB.184.12.3242-3252.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang W, Matte A, Li Y, Kim YS, Linhardt RJ, Su H, Cygler M. Crystal structure of chondroitinase B from Flavobacterium heparinum and its complex with a disaccharide product at 1.7 A resolution. J Mol Biol 1999; 294:1257-1269 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaya D, Tocilj A, Li Y, Myette J, Venkataraman G, Sasisekharan R, Cygler M. Crystal structure of heparinase II from Pedobacter heparinus and its complex with a disaccharide product. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:15525-15535 10.1074/jbc.M512055200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han CS, Chain P. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher In: Arabnia AR, Valafar H, Editors. Proceedings of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology; 2006 June 26-29. CSREA Press. p 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anonymous. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee. 2009 <http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal>

- 23.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova N, Chen IM, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Anderson I, Lykidis A, Kyrpides N. Expert Review of Functional Annotations for Microbial Genomes. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]