Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use among U.S. Adults with Common Neurological Conditions (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Nov 1.

Published in final edited form as: J Neurol. 2010 Jun 11;257(11):1822–1831. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5616-2

Abstract

Our objective was to determine patterns, reasons for, and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in United States (U.S.) adults with common neurological conditions. We compared CAM use between adults with and without common neurological conditions (regular headaches, migraines, back pain with sciatica, strokes, dementia, seizures, or memory loss) using the 2007 National Health Interview Survey of 23,393 sampled U.S. adults. Adults with common neurological conditions used CAM more frequently than those without (44.1% vs. 32.6%, p<0.0001); differences persisted after adjustment. For each CAM modality, adults with common neurological conditions were more likely to use CAM than those without these conditions. Nearly half of adults with back pain with sciatica, memory loss, and migraines reported use of CAM. Mind/body therapies were used the most; alternative medical systems were used the least. Over 50% of adults with common neurological conditions who used CAM had not discussed their use with their health care provider. Those with neurological conditions used CAM more often than those without because of provider recommendation, or because conventional treatments were perceived ineffective or too costly. Significant correlates of CAM use among adults with common neurological conditions include higher than high school education, anxiety in the prior year, living in the west, being a former smoker, and light alcohol use. CAM is used more frequently among adults with common neurological conditions than those without. More research on the efficacy of CAM use for common neurological conditions is warranted.

Keywords: Complementary and alternative medicine, Sciatic back pain, Headaches, Seizures, Stroke, Dementia

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health defines complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered conventional medicine.[4] Studies suggest that CAM use is higher among adults with chronic conditions[18], and is used when conventional treatments are ineffective.[4] Neurological conditions are often chronic and challenging to treat. Moreover, conventional treatments are not fully effective for many common neurological conditions. Thus, patients with neurological conditions may seek CAM therapies even though the efficacy may be unknown. Understanding current patterns of CAM use for neurological conditions is important to focus our research efforts and to help guide clinicians to counsel patients appropriately about benefits and risks.

Little is known about CAM use in adults with common neurological conditions. Few surveys have examined CAM use by Americans with specific neurological conditions, with prevalence estimates ranging from 18%-71%.[6, 16, 21, 25, 26, 28] However, previous surveys generally were conducted in convenience samples and limited to specific conditions.

In this context, we used the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to examine whether adults with common neurological conditions have higher rates of CAM use than the U.S. population. We explored reasons for CAM use and disclosure to conventional health care providers. We examined adults with common neurological conditions to further describe variations in CAM use across conditions and identify correlates of use.

Methods

Data Source

We analyzed data from the 2007 NHIS Sample Adult Core and Alternative Medicine Supplement. The NHIS is a nationally representative survey of the civilian U.S. population that was designed to obtain national estimates of health status, prevalence of medical conditions, and health care access and utilization.[2] NHIS is commonly used by federal agencies to monitor trends in illness and disability and track progress toward achieving national health objectives. NHIS employs a multistage stratified sampling design to select households for face-to face interviews, which are conducted in English and/or Spanish. Hispanic, Asian, and African American populations are oversampled to obtain more precise estimates for these minority populations. One adult, aged 18 or older, was randomly selected from each household to answer the Sample Adult questionnaire, which included questions about common medical conditions. In 2007, NHIS administered an alternative medicine supplement, co-sponsored by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), to better understand the national prevalence of use of CAM therapies and reasons for use.[2] To this end, sampled adults were also asked: “During the past 12 months, have you used (specific therapy)?” We used data on the use of 20 CAM therapies. The final adult sample included 23,393 respondents, with an overall response rate of 67.8%.[2]

Common Neurological Conditions

Since NHIS is a nationally-representative survey, detailed questions were asked only for neurological conditions with a high prevalence in the general population. We examined seven common neurological conditions addressed specifically: (1) regular headaches within the prior 12 months; (2) memory loss within 12 months; (3) stroke within 12 months; (4) severe headache/migraine within 3 months; (5) low back pain, with pain spreading down either leg below the knee(s) within 3 months; (6) ever having seizures; (7) ever having dementia.

Outcomes of Interest

Our primary outcome was use of at least one CAM therapy within the prior 12 months, excluding prayer, vitamin use, special diets, and traditional healers. CAM therapies were grouped into four broad categories: alternative medical systems (Ayurveda, acupuncture, homeopathy, naturopathy), manipulation/bodywork therapies (massage, chiropractic care, Feldenkreis, Alexander technique), biologically-based therapies (herbal therapies, chelation therapy), and mind/body therapies (biofeedback, energy healing, hypnosis, tai chi, yoga, qi gong, meditation, guided imagery, progressive relaxation, deep breathing exercises).

We also examined: (1) disclosure of CAM use to health care providers; and (2) reason for CAM use. For each therapy used in the previous year, respondents were asked about disclosure to conventional practitioners and reasons for CAM use. Respondents then answered yes/no to each of seven items: (1) to improve or enhance energy; (2) for general wellness/general disease prevention; (3) to improve/enhance immune function; (4) because conventional medical treatments did not help; (5) because conventional medical treatments were too expensive; (6) it was recommended by a health care provider; (7) it was recommended by family, friends, or co-workers.

Correlates of CAM Use

We considered potential correlates of CAM use reported previously.[5, 29] Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, race/ethnicity, region of residence, birthplace, educational attainment, and marital status. Potential indicators of illness burden included perceived health status, presence of functional limitations, number of ER visits in past year, self-reported history of chronic medical conditions (diabetes, cancer, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) and depression and or/anxiety in the past year. Indicators of access to care included insurance status, delayed care because of worries about cost, delayed care because could not afford it, and imputed family income provided by NHIS.[1] Measures of health habits included smoking status, physical activity level[15], and alcohol intake.[3]

Statistical Analyses

We used bivariable analyses to compare adults with and without common neurological conditions. We estimated the age-sex adjusted prevalence of CAM use, reasons for, and disclosure of CAM use to healthcare providers. We performed multivariable logistic regression to determine whether differences in CAM use persist between adults with and without common neurological conditions after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, illness burden, access to care, and health habits. We used a stepwise backward elimination process and considered factors associated with CAM use with a p-value <0.15 in bivariable analyses and those found to be important in other studies. [5, 29] Factors with a Wald statistic p-value of ≤ 0.05 and conditions that were considered a priori and have been shown to be important in the literature were retained in the final model.[5, 29] We considered potential confounding by examining a 10% change in the estimated β-coefficient for factors that did not meet these criteria. Since our comparison group of adults without neurological conditions includes individuals with no significant medical conditions, we further performed a stratified analysis to compare the prevalence of CAM use between adults with and without neurological conditions, stratifying by the presence of at least one chronic medical condition versus having no chronic conditions. We defined the subset of respondents with at least one of the following medical conditions: diabetes, cancer, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or arthritis (n=13,618). The remaining subset of respondents had none of these conditions (n=9,775)

We further examined variations in CAM use across the neurological conditions among the subset of adults with common neurological conditions. We first estimated the age-sex adjusted prevalence of CAM use across the conditions, and then used logistic regression to examine whether variations in CAM use persisted after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, illness burden, access to care, and health habits. Next, we used logistic regression (as described above) to identify independent correlates of CAM use in adults with common neurological conditions. This model adjusted for number of neurological conditions (1, ≥2), sociodemographic characteristics, illness burden, access to care, and health habits. Prevalence estimates were computed after excluding missing data; no individual variable had missing data more than 4%. Multivariable models included respondents with complete data on all covariates.

SAS-callable SUDAAN version 9.0.1 (Research Triangle Park, NC) was used to account for the complex sampling design. We weighted the data appropriately so that our results reflect national estimates.[2] The study was approved for exemption by the institutional review boards at our institutions based on 45 CFR 46.101(b) (4) because of de-identified data. This study has thus been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Overall, 6,587 adults had at least one common neurological condition queried, representing an estimated 51.8 million Americans nationwide. Overall, 15.2% reported regular headaches (estimated 33.9 million), 12.3% reported migraines (estimated 27.4 million), 8.4% reported back pain with sciatica (estimated 18.8 million), 5.5% reported memory loss (estimated 12.2 million), 2.0% reported seizures (estimated 4.5 million), 0.6% reported dementia (estimated 1.4 million), and 0.5% reported strokes (estimated 1.1 million). Respondent characteristics differed significantly between those with and without common neurological conditions (Table 1). Compared to adults without common neurological conditions, those with these conditions were more likely to be women, have lower educational attainment and family incomes, perceive their health as fair or poor, have functional limitations, report delaying care because of worries about cost or because it was not affordable, and report other medical or psychiatric conditions.

Table I. Characteristics of adults with and without common neurological conditionsa.

| Characteristic | With Neurological Condition(n=6,587),n (%) | Without Neurological Condition(n=16,806),n (%) | Chi-square p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-24 | 633 (11.0) | 1861 (13.5) | |

| 25-44 | 2390 (37.5) | 6151 (36.6) | |

| 45-64 | 2271 (34.9) | 5504 (33.8) | <0.001 |

| 65-74 | 635 (8.2) | 1782 (8.8) | |

| 75+ | 658 (8.3) | 1508 (7.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2275 (38.0) | 8100 (52.2) | <0.001 |

| Female | 4312 (62.0) | 8706 (47.8) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3845 (68.5) | 10068 (68.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1113 (12.0) | 2513 (11.2) | |

| Hispanic | 1183 (13.2) | 3013 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 275 (3.7) | 933 (4.8) | |

| Other | 171 (2.7) | 279 (1.7) | |

| Education | |||

| < High School | 1459 (19.0) | 2765 (14.1) | |

| High School | 1932 (31.2) | 4590 (27.6) | <0.001 |

| >High School | 3144 (49.0) | 9243 (57.1) | |

| Unknown | 52 (0.7) | 208 (1.2) | |

| Family Imputed Income ($) | |||

| 0-19,999 | 2116 (23.9) | 3617 (14.9) | |

| 20-34,999 | 1372 (20.0) | 3139 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| 35-64,999 | 1559 (26.8) | 4566 (27.8) | |

| >65,000 | 1500 (29.4) | 5484 (41.2) | |

| Perceived Health | |||

| Excellent/Very Good/Good | 4649 (72.5) | 15292 (92.0) | |

| Fair | 1326 (18.9) | 1244(6.5) | <0.001 |

| Poor | 609 (8.6) | 258 (1.4) | |

| History of Medical Conditions | |||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 775 (10.6) | 1261 (6.6) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 654 (9.6) | 1131 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 448 (6.6) | 607 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 365 (5.3) | 441 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2458 (35.0) | 4391 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2128 (31.7) | 3680 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1808 (25.7) | 907 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1675 (25.0) | 926 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 224 (3.3) | 186 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 1105 (16.3) | 1453 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 2296 (34.3) | 2804 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Has 1+ Chronic Medical Condition | 4996 (74.5) | 8622 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| Region of Residence | |||

| Northeast | 1072 (15.9) | 2849 (17.6) | |

| Midwest | 1421 (23.5) | 3801 (24.3) | 0.0184 |

| South | 2540 (38.3) | 6177 (36.1) | |

| West | 1554 (22.3) | 3979 (22.0) | |

| Place of Birth | |||

| US born | 5421 (85.2) | 13394 (83.0) | <0.001 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 3234 (61.3) | 8764 (62.6) | |

| Widowed | 668 (7.1) | 1594 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Divorced/separated | 1272 (12.9) | 2514 (9.9) | |

| Never Married | 1390 (18.5) | 3826 (21.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Uninsured | 1218 (18.3) | 2827 (16.0) | |

| Medicare | 1656 (21.9) | 3343 (16.4) | |

| Medicaid | 665 (8.6) | 800 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Private | 2555 (43.3) | 8425 (54.8) | |

| Other | 493 (7.9) | 1411 (8.9) | |

| Delayed Care: Worried Cost | 1253 (18.1) | 1358 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Delayed Care: Affordability | 1063 (15.5) | 956 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| 1+ Functional Limitation | 2428 (34.8) | 2002 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| # Times to ER in last year | |||

| 0 | 4416 (68.2) | 13817 (82.5) | |

| 1 | 1101 (16.6) | 1844 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| ≥2 | 956 (13.5) | 830 (4.8) | |

| Smoking Status | |||

| Current | 1571 (25.0) | 2801 (17.3) | |

| Former | 1484 (22.9) | 3445 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Never | 3434 (50.6) | 10255 (60.5) | |

| Physical Activity Level | |||

| Low | 3267 (47.5) | 6804 (37.8) | |

| Moderate | 1043 (16.3) | 2531 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| High | 2178 (34.7) | 7147 (44.5) | |

| Alcohol Intake | |||

| Abstainers | 2785 (40.5) | 6450 (36.1) | |

| Light | 2684 (41.9) | 6466 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 630 (10.2) | 2360 (15.1) | |

| Heavy | 284 (4.4) | 822 (5.2) |

Prevalence of CAM Use

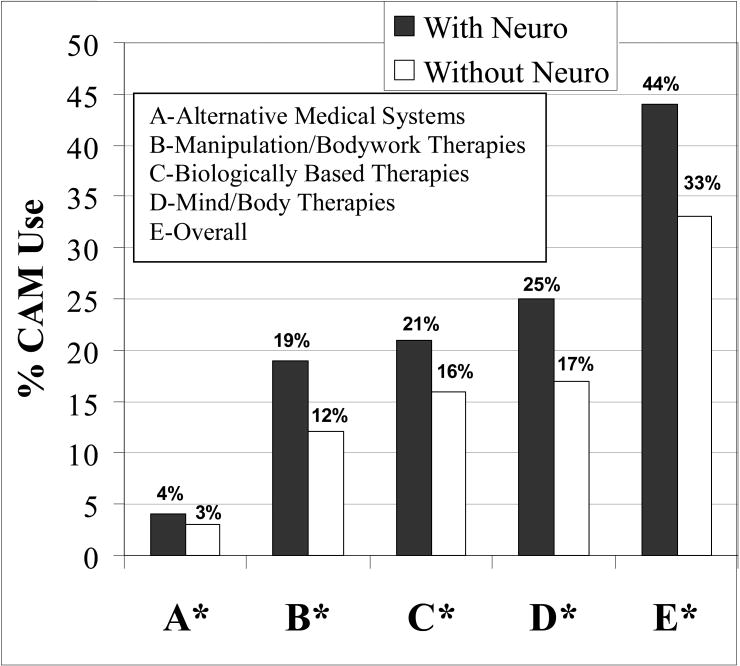

Overall, 44.1% of U.S. adults with common neurological conditions reported using at least one CAM therapy within the prior 12 months, representing an estimated 27.2 million adults, as compared to 32.6% without neurological conditions (p<0.0001), (Figure 1). After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, illness burden, access to care, and health habits, adults with common neurological conditions remained more likely to use CAM than those without these conditions (adjusted OR=1.60, 95% CI [1.46, 1.75]). In the subset of adults with at least one chronic condition, the prevalence of CAM use was higher among adults with neurological conditions compared to those without [45.6 vs. 37.9, p<0.0001]. Similarly, in the subset of adults without chronic conditions, CAM use remained higher among those with neurological conditions compared to those without [39.6 vs. 20.3, p<0.0001].

Fig 1.

Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use across broad CAM categories. Neuro neurological conditions (back pain with sciatica, memory loss, migraines, regular headaches, seizures, stroke, dementia) *=p<0.001; percentages were weighted to reflect national estimates

Mind/body therapies were used most frequently, followed by biologically-based therapies; alternative medical systems were used the least (Figure 1). The most commonly used mind/body therapies across all neurological conditions were deep breathing exercises, meditation, and yoga; herbal therapies were the main biologically-based therapy used; chiropractic care and massage were the main types of manipulation therapies used; and homeopathy and acupuncture were the main types of alternative medical systems used by adults with neurological conditions.

Respondents with neurological conditions reported higher CAM rates than those without if they were non-Hispanic White, had higher than a high school education, private insurance, functional limitations, perceived their health as fair or poor, delayed care because of worries about cost, and delayed care because it was not affordable, after adjusting for age and sex (Table 2).

Table 2. Age-sex adjusted prevalence of CAM use among adults with and without common neurological conditionsa.

| Characteristic | With Neurological Condition, % CAM use | Without Neurological Condition, % CAM use |

|---|---|---|

| Sexb | ||

| Male | 38.4 | 29.5 |

| Female | 47.4 | 36.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 48.1 | 37.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 26.6 | 21.3 |

| Hispanic | 30.1 | 18.0 |

| Asian | 37.9 | 34.8 |

| Other | 50.5 | 39.3 |

| Education | ||

| < High School | 26.6 | 13.8 |

| High School | 38.1 | 23.8 |

| >High School | 52.2 | 41.9 |

| Unknown | 15.9 | 5.7 |

| Family Imputed Income ($) | ||

| 0-19,999 | 33.8 | 23.6 |

| 20-34,999 | 37.5 | 26.3 |

| 35-64,999 | 44.1 | 30.7 |

| >65,000 | 53.0 | 39.4 |

| Delayed Care: Worried Cost | 48.4 | 40.4 |

| Delayed Care: Affordability | 47.8 | 36.6 |

| 1 + Functional Limitation | 40.0 | 34.7 |

| Insurance | ||

| Uninsured | 38.8 | 22.7 |

| Medicare | 40.0 | 30.8 |

| Medicaid | 27.9 | 14.1 |

| Private | 50.1 | 36.2 |

| Other | 49.8 | 31.9 |

| Perceived Health | ||

| Excellent/Very Good/Good | 44.8 | 33.6 |

| Fair | 39.2 | 27.8 |

| Poor | 38.4 | 15.7 |

| Lifetime History of Medical Conditions | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 35.8 | 30.9 |

| Cancer | 41.6 | 44.6 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 46.2 | 26.9 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 45.0 | 26.0 |

| Hypertension | 40.0 | 34.3 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 43.6 | 39.4 |

| Depression | 46.7 | 39.4 |

| Anxiety | 52.1 | 47.2 |

| Region of Residence | ||

| Northeast | 42.9 | 32.6 |

| Midwest | 45.9 | 36.0 |

| South | 37.1 | 26.9 |

| West | 49.5 | 39.0 |

| Place of Birth | ||

| US Born | 45.0 | 34.9 |

| Foreign Born | 31.2 | 23.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Living With Partner | 44.0 | 32.7 |

| Widowed | 34.7 | 20.9 |

| Divorced/separated | 44.3 | 30.2 |

| Never Married | 38.4 | 31.0 |

| # Times to ER in last year | ||

| 0 | 42.9 | 32.7 |

| 1 | 45.3 | 38.3 |

| ≥2 | 44.9 | 32.8 |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Current | 43.2 | 28.2 |

| Former | 51.2 | 43.2 |

| Never | 40.4 | 31.3 |

| Physical Activity Level | ||

| Low | 34.1 | 18.3 |

| Moderate | 48.9 | 37.1 |

| High | 54.6 | 44.6 |

| Alcohol Intake | ||

| Abstainers | 34.7 | 23.2 |

| Light | 49.7 | 38.7 |

| Moderate | 49.0 | 46.9 |

| Heavy | 52.6 | 40.4 |

Disclosure of and Reasons for CAM Use

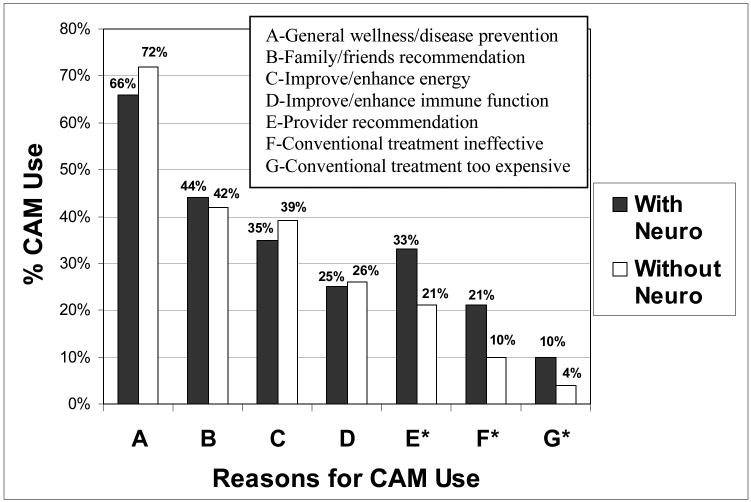

More than half of adults with common neurological conditions did not discuss their CAM use with their health care provider (51%), compared to 60% of adults without neurological conditions (p<0.0001), after adjusting for age and sex. Respondents with neurological conditions used CAM more often than those without because their provider recommended it (32.7% vs. 20.8%), conventional treatment was ineffective (20.5% vs. 10.4%), and conventional treatment was too expensive (9.7% vs. 4.0%) (p<0.001 for all comparisons), after adjusting for age and sex (Figure 2). For both adults with common neurological conditions and those without, the main reasons for CAM use were for general wellness/disease prevention (66.3% vs. 71.8%), family/friends recommendation (43.5% vs. 42.1%), and to improve/enhance energy (35.1% vs. 39.2%), respectively.

Fig 2.

Age-sex adjusted reasons for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among those with and without common neurological conditions. Neuro neurological conditions (back pain with sciatica, memory loss, migraines, regular headaches, seizures, stroke, dementia) *=p<0.001; percentages were weighted to reflect national estimates

Variations in CAM Use across Common Neurological Conditions

The age-sex adjusted prevalence of CAM use varied across neurological conditions, ranging from 47% of respondents with back pain with sciatica, memory loss, and migraines to 18.4% of those with dementia (Table 3). Due to the small sample size of adults with dementia (n=165) and stroke (n=139), only the prevalence of overall CAM use was estimated for these conditions (18.4%, based on n=31; 30.6%, based on n=41, respectively). Across all neurological conditions, mind/body therapies were used most frequently, whereas alternative medical systems were used least frequently. While the prevalence of CAM use was increased modestly in adults with two versus one neurological condition (47.5% versus 41.0%, respectively), the prevalence of CAM use did not vary appreciably in those with three versus four or more neurological conditions (50.0% versus 48.4%, respectively).

Table 3. Variations in age-sex adjusted complementary & alternative medicine (CAM) use across common neurological conditionsa.

| Neurological Condition | Overall CAM use | Mind/Bodyb | Biologicalc | Manipulationd | Alternativee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back Pain with Sciatica (n=2079) | 1102 (47.0) | 538 (25.4) | 428 (21.0) | 444 (23.2) | 101 (3.7) |

| Memory Loss (n=1380) | 819 (46.9) | 329 (27.8) | 283 (23.1) | 188 (16.6) | 51 (4.0) |

| Migraines (n=2886) | 1486 (46.5) | 858 (27.5) | 661 (22.1) | 584 (18.5) | 148 (4.1) |

| Regular Headaches (n=3609) | 2060 (41.1) | 917 (22.9) | 709 (19.8) | 616 (15.7) | 149 (3.6) |

| Seizures (n=423) | 247 (38.7) | 121 (22.9) | 70 (16.6) | 57 (12.5) | * |

| Stroke (n=139) | 41 (30.6) | * | * | * | * |

| Dementia (n=165) | 31 (18.4) | * | * | * | * |

Compared to adults with back pain with sciatica, those with migraine (aOR=1.35, [1.18, 1.55]), regular headaches (aOR=1.20, [1.06, 1.35]), and memory loss (aOR =1.34, [1.10, 1.64]) were more likely to use CAM; those with dementia (aOR =0.40, [0.23, 0.71]) were less likely to use CAM, after adjustment.

Correlates of CAM Use

Among adults with common neurological conditions, factors significantly associated with CAM use included having a high school education or higher, having anxiety in the past year, residing in western region, being a former smoker, and alcohol use (Table 4), after adjustment. Factors significantly associated with a lower likelihood of CAM use included being male, non-Hispanic Black, having an annual household income less than $20,000, and low physical activity, after adjustment.

Table 4. Independent correlates of CAM use among adults with common neurological conditionsa (n=6,587).

| Predictors | Adjustedb OR | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Neurological Conditions: | ||

| 1 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ≥2 | 1.19 | [1.03, 1.38] |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-24 | 0.90 | [0.69, 1.16] |

| 25-44 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 45-64 | 1.21 | [1.03, 1.42] |

| 65-74 | 1.49 | [1.16, 1.92] |

| 75+ | 0.68 | [0.51, 0.90] |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 0.64 | [0.55, 0.75] |

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.54 | [0.44, 0.65] |

| Hispanic | 0.66 | [0.52, 0.85] |

| Asian | 0.97 | [0.69, 1.35] |

| Other | 1.33 | [0.82, 2.14] |

| Region of Residence | ||

| South | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Northeast | 1.09 | [0.91, 1.30] |

| Midwest | 1.24 | [1.00, 1.54] |

| West | 1.51 | [1.25, 1.82] |

| Anxiety | 1.78 | [1.46, 2.16] |

| Being Foreign Born | 0.75 | [0.60, 0.94] |

| Delayed Care: Worried Cost | 1.29 | [1.08, 1.54] |

| Education | ||

| <High School | 1.00 (reference) | |

| High School | 1.29 | [1.04, 1.58] |

| >High school | 2.04 | [1.67, 2.48] |

| Family Imputed Income ($) | ||

| 0-19,999 | 0.63 | [0.50, 0.78] |

| 20-34,999 | 0.71 | [0.58, 0.87] |

| 35-64,999 | 0.83 | [0.69, 1.00] |

| >65,000 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.18 | [1.03, 1.36] |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Current | 1.14 | [0.95, 1.38] |

| Former | 1.43 | [1.20, 1.69] |

| Never | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Physical Activity Level | ||

| Low | 0.50 | [0.43, 0.58] |

| Moderate | 0.84 | [0.71, 1.00] |

| High | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Alcohol Intake | ||

| Abstainer | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Light | 1.40 | [1.19, 1.64] |

| Moderate | 1.36 | [1.06, 1.75] |

| Heavy | 1.65 | [1.20, 2.28] |

Discussion

CAM was used more frequently among U.S. adults with common neurological conditions than those without. Adults with back pain with sciatica, memory loss, migraines, or regular headaches used CAM more often than those with seizures, stroke, or dementia. Mind/body therapies were used the most; alternative medical systems were used the least. Despite the high prevalence of CAM, approximately one-half of adults with common neurological conditions did not discuss their CAM use with their health care provider. Adults without common neurological conditions were more likely than those without these conditions to report using CAM because their provider recommended it or because conventional treatments were perceived ineffective or too expensive.

The estimated prevalence of the neurological conditions examined in the NHIS is consistent with previously reported rates in the general population.[10, 11, 14, 19, 20] Rates of CAM use among adults with common neurological conditions in this survey (44.1%) fell within the wide range of published prevalence rates of CAM use for various neurological conditions. [6, 16, 21, 25, 26, 28] Consistent with studies of other chronic conditions, we found that CAM use was higher among women, those with higher educational attainment and incomes. [5, 29]

Thus, CAM use among adults with neurological conditions is popular. Research regarding its efficacy in neurological conditions is promising. Based on evidence from 39 trials, the US Headache Consortium treatment guidelines suggest that complementary therapies (relaxation training, thermal biofeedback combined with relaxation training, EMG biofeedback, and cognitive behavioral therapy) may be considered as treatment options for prevention of migraine, with Grade A evidence.[7] In the same guidelines, they did recognize that evidenced-based treatment recommendations are not yet possible regarding the use of hypnosis, acupuncture, or cervical manipulation in the treatment of migraine headaches. A recent randomized trial of yoga for the treatment of migraine without aura demonstrated a significant reduction in migraine headache frequency and associated clinical features.[13] A recent systematic review also concluded that there is strong evidence for mind/body therapies for migraine treatment.[27]

Evidence is emerging for CAM interventions in back pain management. A meta-analysis of acupuncture for low back pain concluded that acupuncture is more effective than sham treatment for short-term relief of chronic pain.[17] Another meta-analysis showed only fair evidence for the effective treatment of chronic low back pain with acupuncture, massage, and yoga.[8] There is only fair evidence to suggest that spinal manipulation may have small to moderate benefits for treatment of acute low back pain. A trial comparing active chiropractic manipulation to simulated manipulations in patients with acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion revealed that active treatment was more effective in treating pain than simulated spinal manipulation.[23]

Thus, there is promising evidence for certain CAM treatments for headaches and back pain. Further research is needed to continue to evaluate the efficacy of CAM in these and in other neurological conditions. Many previous studies were preliminary or had methodological issues such as small sample sizes and/or inadequate control groups. It is also important for patients and physicians to recognize that some CAM therapies may be potentially dangerous. For example, Ginkgo has anti-platelet effects that could cause unnecessary bleeding in stroke patients or interact with anticoagulants. Case reports of some herbs suggest proconvulsive effects.[22] Many common herbs (e.g. Ginkgo biloba and St. John's wort) interact with anti-epileptic therapies and other prescribed drugs through alterations of hepatic metabolism.[9, 22, 24] Potential for herb-drug interactions also pertain to concomitant medications which patients take for non-neurological chronic medical conditions; many of these conditions were prevalent among NHIS respondents with neurological conditions. Most concerning, however are case reports of stroke following chiropractic manipulation.[12]

There is a substantial disconnect between patients and doctors about CAM use. Surprisingly, one-third of adults with common neurological conditions reported using CAM because their provider recommended it. Although anecdotally many physicians do not feel comfortable recommending some CAM therapies because of the paucity of data on its efficacy in neurological conditions, many patients reported using these therapies anyway, and often did not inform their health care providers. We found it interesting that acupuncture, which has been studied frequently and found to be effective in patients with some neurological conditions, was used less frequently by adults with common neurological conditions than most other CAM modalities examined. Clinicians should make a concerted effort to ask patients about their CAM use, discussing possible risks and benefits.

Our study has limitations. NHIS is cross-sectional, relies on self-reporting, and is subject to misclassification and recall bias. NHIS is conducted in the U.S. and may not be generalizable to other countries. NHIS includes details about a limited number of neurological conditions, selecting only conditions with a high prevalence in the general population. Patients with other conditions commonly seen by neurologists, such as multiple sclerosis, are not fully addressed. Moreover, the severity of the conditions is not assessed. Even though respondents reported use of CAM from the prior 12 months, some conditions are reported if present in the prior 3 months. Because of small sample sizes, our study could not assess whether CAM was used specifically for the conditions examined.

In summary, CAM use is common in U.S. adults with neurological conditions, and used more frequently by adults with these conditions than those without. This finding supports our hypothesis that patients with neurological conditions may seek alternative therapies because of the chronicity of their problems and the lack of full relief from conventional therapies. Most physicians do not know about their patients' CAM use, thus it is critical to reinforce the importance of clinicians asking and discussing the use of CAM with their patients. Although there is a high prevalence of CAM use among adults with common neurological conditions nationally, there is only limited evidence for its efficacy. Thus, a chasm continues to exist between our scientific knowledge of these therapies and their use by patients. Robust trials are critically needed to bridge this gap and to provide evidence on the efficacy of CAM therapies in patients with neurological conditions, so that patients suffering from these conditions can benefit from treatments that are shown to be effective and can be counseled about those with potential adverse effects.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wells was supported by an institutional National Research Service Award Number T32AT000051 from the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Phillips was supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award K24AT000589 and Dr. McCarthy was supported by R03AT002236, also from NCCAM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Erwin Wells, Email: Rebecca_Wells@hms.harvard.edu, Division for Research and Education in Complementary and Integrative Medical Therapies, Harvard, Medical School; Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA; Osher Research Center, Harvard Medical School, Landmark Center, 401 Park Drive, Suite 22A-West, Boston, MA 02215, 617-384-8552 (phone), 617-384-8555 (fax).

Russell S. Phillips, Email: rphillip@bidmc.harvard.edu, Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical, Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, General Medicine, YA-111, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215.

Steven C. Schachter, Email: sschacht@bidmc.harvard.edu, Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Neurology, Kirstein 478, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215.

Ellen P. McCarthy, Email: emccarth@bidmc.harvard.edu, Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical, Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, General Medicine, CO-1309, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215.

References

- 1.CDC National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey 2007 Imputed Family Income. [8 January 2009];2008 http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/nhis/2007imputedincome.htm.

- 2.CDC National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey 2007 Survey Description Document. [8 January 2009];2007 ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2007/srvydesc.pdf.

- 3.Health, United States 2007. [14 July 2009];2007 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus07.pdf.

- 4.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertisch SM, Wee CC, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Alternative mind-body therapies used by adults with medical conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunelli B, Gorson KC. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by patients with peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;218:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JK, Penzien DB, Wall EM. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: behavioral and physical treatments. US Headache Consortium 2000.2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain S, American College of P Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst E. The risk-benefit profile of commonly used herbal therapies: Ginkgo, St. John's Wort, Ginseng, Echinacea, Saw Palmetto, and Kava. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:42–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-1-200201010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farlow MR. Alzheimer's Disease. In: Miller MF, editor. Continuum. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Hagerstown: 2007. pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jallon P. Epilepsy and epileptic disorders, an epidemiological marker? Contribution of descriptive epidemiology. Epileptic Disord. 2002;4:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeret JS, Bluth M. Stroke following chiropractic manipulation. Report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:210–213. doi: 10.1159/000047778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John PJ, Sharma N, Sharma CM, Kankane A. Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: a randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2007;47:654–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konstantinou K, Dunn KM. Sciatica: review of epidemiological studies and prevalence estimates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2464–2472. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318183a4a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushi LH, Fee RM, Folsom AR, Mink PJ, Anderson KE, Sellers TA. Physical activity and mortality in postmenopausal women. Jama. 1997;277:1287–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liow K, Ablah E, Nguyen JC, Sadler T, Wolfe D, Tran KD, Guo L, Hoang T. Pattern and frequency of use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with epilepsy in the midwestern United States. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, Forys K, Ernst E. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:651–663. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MF, Bellizzi KM, Sufian M, Ambs AH, Goldstein MS, Ballard-Barbash R. Dietary supplement use in individuals living with cancer and other chronic conditions: a population-based study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul SL, Srikanth VK, Thrift AG. The large and growing burden of stroke. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:786–793. doi: 10.2174/138945007781077418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen BK. Epidemiology of headache. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:774–777. doi: 10.1177/033310240102100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan M, Johnson MS. Use of alternative medications in patients with neurologic disorders. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1540–1545. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuels N, Finkelstein Y, Singer SR, Oberbaum M. Herbal medicine and epilepsy: proconvulsive effects and interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2008;49:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S. Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: a randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations. Spine J. 2006;6:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schachter SC. Complementary and alternative medical therapies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:184–189. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f47918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz CE, Laitin E, Brotman S, LaRocca N. Utilization of unconventional treatments by persons with MS: is it alternative or complementary? Neurology. 1999;52:626–629. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinto L, Yadav V, Morris C, Lapidus JA, Senders A, Bourdette D. Demographic and health-related factors associated with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:94–100. doi: 10.1191/1352458506ms1230oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahbeh H, Elsas SM, Oken BS. Mind-body interventions: applications in neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:2321–2328. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314667.16386.5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasner M, Klier H, Borasio GD. The use of alternative medicine by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeh GY, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]