Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications (original) (raw)

Abstract

Summary: A combination of bisulfite treatment of DNA and high-throughput sequencing (BS-Seq) can capture a snapshot of a cell's epigenomic state by revealing its genome-wide cytosine methylation at single base resolution. Bismark is a flexible tool for the time-efficient analysis of BS-Seq data which performs both read mapping and methylation calling in a single convenient step. Its output discriminates between cytosines in CpG, CHG and CHH context and enables bench scientists to visualize and interpret their methylation data soon after the sequencing run is completed.

Availability and implementation: Bismark is released under the GNU GPLv3+ licence. The source code is freely available from www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/bismark/.

Contact: felix.krueger@bbsrc.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cytosine methylation of DNA serves as an important epigenetic mechanism to control gene expression, silencing or genomic imprinting both during development and in the adult (Law and Jacobsen, 2010). Aberrant methylation has been associated with a variety of diseases, including cancer (Robertson, 2005). Current massively parallel sequencing methods to study DNA methylation include enrichment-based methods such as methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP-Seq) or methylated DNA binding domain sequencing (MBD-Seq), as well as direct sequencing of sodium bisulfite-treated DNA (BS-Seq) [methods compared in (Harris et al., 2010)].

Bisulfite treatment of DNA leaves methylated cytosines unaffected, while non-methylated cytosines are converted into uracils. Subsequent PCR amplification converts these uracils into thymines. For any given genomic locus, bisulfite treatment and subsequent PCR amplification give rise to four individual strands of DNA which can potentially all end up in a sequencing experiment (Supplementary Material). Mapping of bisulfite-treated sequences to a reference genome constitutes a significant computational challenge due to the combination of: (i) the reduced complexity of the DNA code; (ii) up to four DNA strands to be analysed; and (iii) the fact that each read can theoretically exist in all possible methylation states. Even though there are a number of excellent short read mapping tools available, e.g. Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009), these do not perform bisulfite mapping themselves.

2 SOFTWARE DESCRIPTION AND DISCUSSION

Bisulfite libraries are of two distinct types (Chen et al., 2010): in the first scenario the sequencing library is generated in a directional manner, i.e. the actual sequencing reads will correspond to a bisulfite converted version of either the original forward or reverse strand (Lister et al., 2009). In a second scenario, strand specificity is not preserved, which means all four possible bisulfite DNA strands are sequenced at roughly the same frequency (Cokus et al., 2008; Popp et al., 2010).

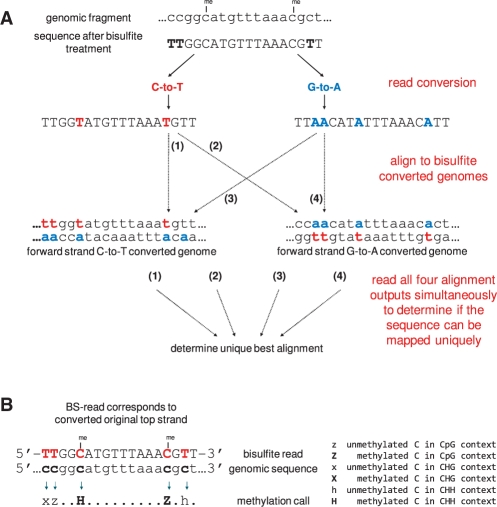

As the strand identity of a bisulfite read is a priori unknown, our bisulfite mapping tool Bismark aims to find a unique alignment by running four alignment processes simultaneously. First, bisulfite reads are transformed into a C-to-T and G-to-A version (equivalent to a C-to-T conversion on the reverse strand). Then, each of them is aligned to equivalently pre-converted forms of the reference genome using four parallel instances of the short read aligner Bowtie (Fig. 1A). This read mapping enables Bismark to uniquely determine the strand origin of a bisulfite read. Consequently, Bismark can handle BS-Seq data from both directional and non-directional libraries. Since residual cytosines in the sequencing read are converted in silico into a fully bisulfite-converted form before the alignment takes place, mapping performed in this manner handles partial methylation accurately and in an unbiased manner.

Fig. 1.

Bismark's approach to bisulfite mapping and methylation calling. (A) Reads from a BS-Seq experiment are converted into a C-to-T and a G-to-A version and are then aligned to equivalently converted versions of the reference genome. A unique best alignment is then determined from the four parallel alignment processes [in this example, the best alignment has no mismatches and comes from thread (1)]. (B) The methylation state of positions involving cytosines is determined by comparing the read sequence with the corresponding genomic sequence. Depending on the strand a read mapped against this can involve looking for C-to-T (as shown here) or G-to-A substitutions.

A similar approach was demonstrated to work well for single-end reads with the tool BS Seeker, which was developed independently of Bismark (Chen et al., 2010). BS Seeker outperformed earlier generation BS-Seq mapping programs such as BSMAP, RMAP-bs or MAQ in terms of mapping efficiency, accuracy and required CPU time. Even though the principle of both tools is similar, Bismark offers a number of advantages over BS Seeker which are summarized in Table 1. For a test dataset [15 million reads taken from SRR020138 (Lister et al., 2009), trimmed to 50 bp, mapped to the human genome build NCBI36, one mismatch allowed], a direct comparison of the two tools returned a very similar number of alignments in a similar time scale [aligned reads/mapping efficiency/CPU time: 9 633 448/64.2%/42 min (Bismark); 9 664 184/64.4%/29 min (BS Seeker)]. Due to the way Bismark determines uniquely best alignments, it is less likely to report non-unique alignments; however, this comes at the cost of a slightly increased run time (for details see Supplementary Material).

Table 1.

Feature comparison of Bismark and BS Seeker

| Feature | Bismark | BS Seeker |

|---|---|---|

| Bowtie instances (directional/non-directional) | 4 | 2/4 |

| Single-end (SE)/paired-end (PE) support | Yes/yes | yes/no |

| Variable read length (SE/PE) | Yes/yes | no/NA |

| Adjustable insert size (PE) | Yes | NA |

| Uses basecall qualities for FastQ mapping | Yes | No |

| Adjustable mapping parameters | 5 | 2 |

| Directional/non-directional library support | Yes/yes | Yes/yesa |

Many previous BS-Seq programs were solely mapping applications, which meant that extracting the underlying methylation data required a lot of post-processing and computational knowledge. Bismark aims to generate a bisulfite mapping output that can be readily explored by bench scientists. Thus, in addition to the alignment process Bismark determines the methylation state of each cytosine position in the read (Fig. 1B). DNA methylation in mammals is thought to occur predominantly at CpG dinucleotides; however, a certain amount of non-CpG methylation has been shown in embryonic stem cells (Lister et al., 2009). In plants, methylation is quite common in both the symmetric CpG or CHG, and asymmetric CHH context (whereby H can be either A, T or C) (Feng et al., 2010; Law and Jacobsen, 2010). To enable methylation analysis in different sequence contexts and/or model organisms, methylation calls in Bismark take the surrounding sequence context into consideration and discriminate between cytosines in CpG, CHG and CHH context.

The primary mapping output of Bismark contains one line per read and shows a number of useful pieces of information such as mapping position, alignment strand, the bisulfite read sequence, its equivalent genomic sequence and a methylation call string (Supplementary Material). This mapping output can be subjected to post-processing (Supplementary Material) or can be used to extract the methylation information at individual cytosine positions. This secondary methylation-state output can be generated using a flexible methylation extractor component that accompanies Bismark. The methylation output discriminates between sequence context (CpG, CHG or CHH) and can be obtained in either a comprehensive (all alignment strands merged) or alignment strand-specific format. The latter can be very useful to study asymmetric methylation (hemi- or CHH methylation) in a strand-specific manner. The output of the methylation extractor will create one entry (or line) per cytosine, whereby the strand information is used to encode its methylation state: ‘+’ indicates a methylated and ‘−’ a non-methylated cytosine. This output can be converted into other alignment formats such as SAM/BAM, or imported into genome browsers, such as SeqMonk, where it can be visualized and further explored by the researcher without requiring additional computational expertise.

3 CONCLUSIONS

We present Bismark, a software package to map and determine the methylation state of BS-Seq reads. Bismark is easy to use, very flexible and is the first published BS-Seq aligner to seamlessly handle single- and paired-end mapping of both directional and non-directional bisulfite libraries. The output of Bismark is easy to interpret and is intended to be analysed directly by the researcher performing the experiment.

Funding: Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

REFERENCES

- Chen P.Y., et al. BS Seeker: precise mapping for bisulfite sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokus S.J., et al. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature. 2008;452:215–219. doi: 10.1038/nature06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., et al. Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8689–8694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002720107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R.A., et al. Comparison of sequencing-based methods to profile DNA methylation and identification of monoallelic epigenetic modifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law J.A., Jacobsen S.E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R., et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp C., et al. Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature. 2010;463:1101–1105. doi: 10.1038/nature08829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K.D. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data