The Dicey Role of Dicer: Implications for RNAi Therapy (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Sep 12.

Abstract

The dynamic properties of RNA interference (RNAi) in cancer biology have led investigators to pursue with significant interest its role in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. We recently reported that decreased expression of key RNAi enzymes, Dicer and Drosha, in epithelial ovarian cancers was associated with poor clinical outcome in patients. Dicer expression was also functionally relevant in that targeted silencing was limited with RNAi fragments that require Dicer function compared with those that do not. Together, this and other studies suggest that RNAi machinery expression may affect key pathways in tumorigenesis and cancer biology. Understanding alterations in the functional RNAi machinery is of fundamental importance as we strive to develop novel therapies using RNAi strategies.

The emergence of RNA interference (RNAi) research has led to a better understanding of cancer biology. Fire and Mello first introduced this concept in 1998 and laid the foundation for this process by which cell systems have the inherent ability to alter gene expression (1). RNAi is a post-transcriptional gene silencing mechanism that can be triggered by small RNA molecules such as microRNA (miRNA) and short interfering RNA (siRNA). RNAi complexes are endogenously produced within cells to target host RNA sequences that result in gene silencing. In addition to regulation of normal biological processes in humans, miRNAs seem to serve an important role in human cancers. Recent studies show that components of RNAi pathways may serve as valuable diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools in cancer research (2–5).

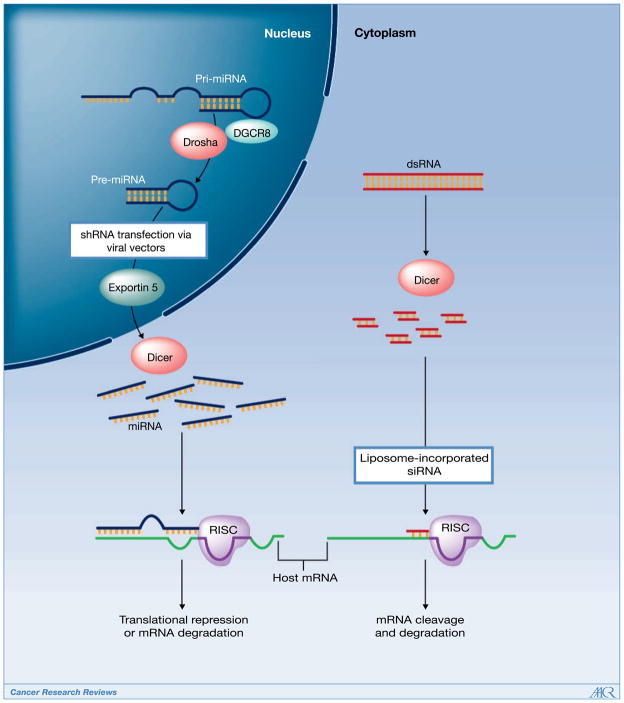

MiRNAs are often highly conserved single-stranded RNA sequences in the genome, which have partial complementarity in binding to a host’s target gene. MiRNA production begins in the nucleus from several kilobase-long primary miRNAs (pri-miRNA). These pri-miRNAs undergo cleavage to produce short hairpin-shaped intermediates known as precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA), which are approximately 70 nucleotides in length (Fig. 1). Drosha, a RNAse III enzyme, along with the DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGCR8), processes the precursors prior to translocation to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5. Subsequently, pre-miRNAs are cleaved by Dicer, also an RNAse III enzyme, resulting in mature miRNAs. SiRNA, an approximately 21-nucleotide single-stranded sequence, is derived within the cytoplasm and does not require processing by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Mature miRNAs and siRNAs are then activated through the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which produce host mRNA degradation and/or translational repression upon binding to the target. Exogenous constructs of either siRNAs or short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) can also be introduced into cells through transfection (Fig. 1; refs. 6, 7). ShRNAs are introduced through viral vectors to produce stable gene silencing, whereas siRNA transfections are more transient. Through these applications, RNAi has been a critical asset for investigators to dissect and identify pathways associated with cancer development and spread.

Figure 1.

Multiple components of the RNAi cascade are critical toward maturation of miRNA and siRNA complexes in humans. Altered expression of these entities is associated with poor outcomes and may limit RNAi function in cells. Introduction of exogenous RNAi sequences, such as siRNA, that bypass this machinery, may provide a novel pathway toward drug development in cancer therapeutics.

The importance of miRNAs in human diseases, including cancer, is becoming more apparent with recent discoveries. Genetic analyses have shown altered expression of miRNAs in many human cancers. For example, altered expression of the let-7, miR-15a, and miR-16-1 miRNA families have been shown to lead to the development and progression of multiple malignancies, including lung, breast, ovary, leukemia, and cervical (2). In addition, expression profiles of miRNA clusters show potential utility as prognostic variables in these and other malignancies (4, 8), thus, strengthening the critical need to decipher the functional role of miRNAs in cancer pathogenesis. On the basis of these and other studies, we asked whether the differential expression of RNAi processing machinery could parallel the clinical associations observed with patient outcome. To answer this question, we examined a large cohort (N = 111) of ovarian cancer specimens for Dicer and Drosha expression (9). Interestingly, expression of either enzyme was decreased in a substantial proportion of ovarian cancers compared with normal ovarian epithelium (9). Moreover, 39% of the tumors had decreased levels of both Dicer and Drosha (9). We also reported that expression levels of Dicer or Drosha were associated with patient outcome. In univariate analysis, low Dicer mRNA levels were associated with advanced tumor stage (P = 0.007), and low Drosha with suboptimal tumor cytoreduction (P = 0.02), a poor prognostic factor in ovarian cancer (9). Decreased expression of one or both enzymes was also associated with decreased patient survival (9). For example, the median overall survival of patients with low tumoral Dicer expression was 2.33 years versus 9.25 years for those with high expression (P < 0.001; ref. 9). Low Drosha expression was also associated with decreased patient survival. These poor survival outcomes were also validated in independent data sets of patients with ovarian, breast, and lung carcinoma (9). Others have examined the role of RNAi machinery expression in tumor types such as lung (10, 11), esophageal (12), and prostate cancers (13). Karube and Chiosea reported similar findings in lung cancer patients as observed in our study (10, 11). However, high Dicer expression was a poor prognostic factor in patients with prostate and esophageal carcinoma (12, 13). The differences in these reports have not been fully elucidated; however, these data suggest that RNAi regulatory processes may be tumor specific. Although not reported in our study, other components in the RNAi cascade may also play a critical role in affecting patient outcome. For example, deficiency in Exportin-5 may limit miR-NA production as showed by Yi and colleagues (14). The Argonaute family of binding proteins, which are critical to host RNA degradation via RISC may also regulate upstream RNAi machinery, thereby, reducing miRNA function (15).

The functional role of most miRNAs is largely unknown as their imperfect complementarity seems to afford multiple target binding, leading to difficulty in identifying miRNA target genes (16). However, investigators continue to make progress in surpassing this difficult challenge as recently reported by Chi and colleagues (17). Nevertheless, the importance of these RNAs has become more evident in human cancer. For example, altered miRNA expression has been linked to inhibiting or promoting the activity of key tumor-suppressor genes or oncogenes, such as p53 or MYC, respectively, thereby leading to tumor formation in preclinical models (2, 18–20). Therefore, we asked whether Dicer expression could affect the efficiency of miRNA production in cancer cells and possibly explain prior associations discovered with poor patient outcome. We examined the functional relevance of RNAi machinery in ovarian cancer cells with variable Dicer expression and showed that silencing the galectin-3 gene in ovarian cancer cells with low Dicer was successful only by using siRNA, but not with the longer shRNA fragments (9). In cells with high Dicer, no significant differences between both models were observed.

In addition to identifying components critical to key pathways in tumor formation and progression, RNAi has become an invaluable tool for cancer therapeutics. Although many new therapeutic targets have been identified, it is not possible to target all of these with conventional approaches such as small molecule inhibitors or fully humanized antibodies. MiRNAs may offer an advantage in this case because of effects on multiple downstream pathways or targets (4). Moreover, most small molecule inhibitors lack specificity and can be associated with intolerable side effects. Similarly, although monoclonal antibodies have shown promise against specific targets such as VEGF, their use is limited to either ligands or surface receptors. Therefore, RNAi has recently become a powerful tool not only in protein function delineation and gene discovery, but also in drug development.

The transition of RNAi technology from the laboratory to the clinic has been difficult, but promising. Several types of RNAi applications have been used in therapy in which RNA sequences are administered in vitro and/or in vivo. One popular method involves the use of viral vectors for incorporation of the miRNA (or shRNA) sequence into the cell. Delivery applications that are currently used in laboratory and clinical research include adeno-associated viral (AAV), lentiviral, adenoviral, and retroviral vectors (19, 21–23). In addition to diseases such as HIV, viral systems are being developed for cancer therapy. For example, AAV miRNA vectors have successfully been shown to inhibit tumor growth in an in vivo liver cancer model (19). Similar findings have been reported in leukemia, lung, and prostate models (2, 24, 25). Although minimal host toxicities were observed in murine models using viral systems, other studies suggest potential limitations may develop owing to the requirements for RNAi processing machinery in normal organ function. For example, Grimm and colleagues reported significant morbidity and mortality in murine models when administering shRNA viral vectors (26). The authors suggested that exogenous delivery of viral vector shRNA constructs may “overwhelm” the endogenous miRNA competition for RNAi maturation (26). In cells with low machinery expression, as reported in our article, these scenarios could have detrimental effects in host toxicity and therapeutic efficacy, thereby, favoring an alternative strategy that would bypass the cellular RNAi machinery.

The emergence of novel nonviral therapeutic applications, such as nanoliposomes, to deliver siRNA constructs has also become widely accepted and promising for future clinical development. Evidence suggests that siRNA constructs can deliver long duration of target inhibition as well as reduced toxicity compared with some of the other approaches. However, the delivery of siRNA constructs has been challenging and the rate-limiting step for in vivo therapy. Delivery methods that are effective for other nucleic acids are not necessarily always effective for RNAi delivery. Early attempts at delivery of “naked” siRNA, high-pressure siRNA injections, and intratumoral injections have been investigated with limited success. A highly promising option involves incorporating siRNA into nanoliposomes prior to in vivo delivery. Liposomes are a form of nanoparticles that function as carriers and act as a slow-release carrier for the drug in diseased tissue. Prior studies from our laboratory have showed effective in vivo delivery of gene-specific siRNA sequences incorporated into neutrally charged nanoliposomes for a range of targets in ovarian cancer models (27–29). In addition to minimal host toxicity, we observed remarkable gene-specific silencing. To date, this method has been validated in other laboratories as an effective therapeutic approach in colorectal, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer models (30–32). The neutral nanoliposomes with siRNA were delivered through either the intravenous or intraperitoneal route. Although not a complete list, several clinical trials are ongoing with siRNA therapeutics including patients with either macular degeneration, AIDS, pachyonychia congenital, malignant melanoma, acute renal failure, or hepatitis B (33). To the best of our knowledge, however, such trials using systemic delivery of siRNA for treatment of cancer patients remain to be initiated.

In summary, RNAi applications have become one of the most powerful tools for biomedical research today and may be the novel application needed for advancing cancer therapy. Recently, we reported that RNAi machinery expression has a direct impact on survival in patients with ovarian cancer. Furthermore, as we devote future research toward incorporating RNAi therapeutics into clinical trials, we must take note that these findings may play a pivotal role in optimizing the efficacy of the specific RNAi construct being used.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Program Project Development Grant, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Ovarian Cancer SPORE grant P50 CA083639, NIH grants CA110793, and CA109298, DOD grant OC093146, T32 Training Grant CA101642, the Gynecologic Cancer Foundation, the Zarrow Foundation, the Betty Ann Asche Murray Distinguished Professorship, the Marcus Foundation, and the Blanton-Davis Ovarian Cancer Research Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–11. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medina PP, Slack FJ. microRNAs and cancer: an overview. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2485–92. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negrini M, Nicoloso MS, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and cancer-new paradigms in molecular oncology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah PP, Hutchinson LE, Kakar SS. Emerging role of microRNAs in diagnosis and treatment of various diseases including ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2009;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–51. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandy P, Ventura A, Jacks T. Mammalian RNAi: a practical guide. Biotechniques. 2005;39:215–24. doi: 10.2144/05392RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merritt WM, Lin YG, Han LY, et al. Dicer, Drosha, and outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2641–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiosea S, Jelezcova E, Chandran U, et al. Overexpression of Dicer in precursor lesions of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2345–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karube Y, Tanaka H, Osada H, et al. Reduced expression of Dicer associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:111–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugito N, Ishiguro H, Kuwabara Y, et al. RNASEN regulates cell proliferation and affects survival in esophageal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7322–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiosea S, Jelezcova E, Chandran U, et al. Up-regulation of dicer, a component of the MicroRNA machinery, in prostate adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1812–20. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diederichs S, Jung S, Rothenberg SM, Smolen GA, Mlody BG, Haber DA. Coexpression of Argonaute-2 enhances RNA interference toward perfect match binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800803105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–86. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O’Donnell KA, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kent OA, Mendell JT. A small piece in the cancer puzzle: microRNAs as tumor suppressors and oncogenes. Oncogene. 2006;25:6188–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grimm D, Pandey K, Kay MA. Adeno-associated virus vectors for short hairpin RNA expression. Methods Enzymol. 2005;392:381–405. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)92023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. Strategies for silencing human disease using RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:173–84. doi: 10.1038/nrg2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoo JY, Kim JH, Kwon YG, et al. VEGF-specific short hairpin RNA-expressing oncolytic adenovirus elicits potent inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Mol Ther. 2007;15:295–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonci D, Coppola V, Musumeci M, et al. The miR-15a-miR-16–1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nat Med. 2008;14:1271–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calin GA, Cimmino A, Fabbri M, et al. MiR-15a and miR-16–1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5166–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800121105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halder J, Kamat AA, Landen CN, Jr, et al. Focal adhesion kinase targeting using in vivo short interfering RNA delivery in neutral liposomes for ovarian carcinoma therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4916–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landen CN, Merritt WM, Mangala LS, et al. Intraperitoneal delivery of liposomal siRNA for therapy of advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1708–13. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merritt WM, Lin YG, Spannuth WA, et al. Effect of interleukin-8 gene silencing with liposome-encapsulated small interfering RNA on ovarian cancer cell growth. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:359–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray MJ, Van Buren G, Dallas NA, et al. Therapeutic targeting of neuropilin-2 on colorectal carcinoma cells implanted in the murine liver. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:109–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villares GJ, Zigler M, Wang H, et al. Targeting melanoma growth and metastasis with systemic delivery of liposome-incorporated protease-activated receptor-1 small interfering RNA. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9078–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin P, Arumugam T, Pan X, et al. Neutral liposome-coupled siRNA delivery against EphA2 receptor sensitizes gemcitabine resistant orthotopic pancreatic tumors in vivo. [Abstr #5728]. San Diego (CA). 99th AACR Annual Meeting; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrey K, Suchit A, Nishant M, Vibha R. RNA interference: Emerging diagnostics and therapeutics tool. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:273–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]