IL28B, HLA-C, and KIR Variants Additively Predict Response to Therapy in Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection in a European Cohort: A Cross-Sectional Study (original) (raw)

Vijayaprakash Suppiah and colleagues show that genotyping hepatitis C patients for the IL28B, HLA-C, and KIR genes improves the ability to predict whether or not patients will respond to antiviral treatment.

Abstract

Background

To date, drug response genes have not proved as useful in clinical practice as was anticipated at the start of the genomic era. An exception is in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection with pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin (PegIFN/R). Viral clearance is achieved in 40%–50% of patients. Interleukin 28B (IL28B) genotype predicts treatment-induced and spontaneous clearance. To improve the predictive value of this genotype, we studied the combined effect of variants of IL28B with human leukocyte antigen C (HLA-C), and its ligands the killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR), which have previously been implicated in HCV viral control.

Methods and Findings

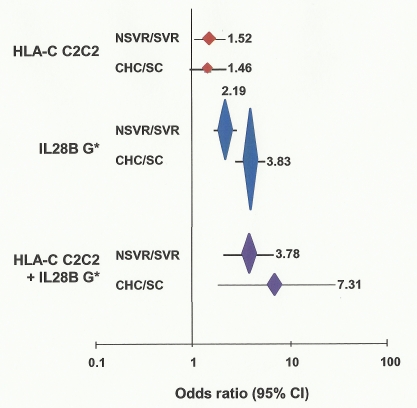

We genotyped chronic hepatitis C (CHC) genotype 1 patients with PegIFN/R treatment-induced clearance (n = 417) and treatment failure (n = 493), and 234 individuals with spontaneous clearance, for HLA-C C1 versus C2, presence of inhibitory and activating KIR genes, and two IL28B SNPs, rs8099917 and rs12979860. All individuals were Europeans or of European descent. IL28B SNP rs8099917 “G” was associated with absence of treatment-induced clearance (odds ratio [OR] 2.19, p = 1.27×10−8, 1.67–2.88) and absence of spontaneous clearance (OR 3.83, p = 1.71×10−14, 2.67–5.48) of HCV, as was rs12979860, with slightly lower ORs. The HLA-C C2C2 genotype was also over-represented in patients who failed treatment (OR 1.52, p = 0.024, 1.05–2.20), but was not associated with spontaneous clearance. Prediction of treatment failure improved from 66% with IL28B to 80% using both genes in this cohort (OR 3.78, p = 8.83×10−6, 2.03–7.04). There was evidence that KIR2DL3 and KIR2DS2 carriage also altered HCV treatment response in combination with HLA-C and IL28B.

Conclusions

Genotyping for IL28B, HLA-C, and KIR genes improves prediction of HCV treatment response. These findings support a role for natural killer (NK) cell activation in PegIFN/R treatment-induced clearance, partially mediated by IL28B.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Editors' Summary

Background

About 170 million people harbor long-term (chronic) infections with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and 3–4 million people are newly infected with the virus every year. HCV—a leading cause of chronic hepatitis (inflammation of the liver)—is spread though contact with infected blood. Transmission can occur during medical procedures (for example, transfusions with unscreened blood or reuse of inadequately sterilized medical instruments) but in developed countries, where donated blood is routinely screened for HCV, the most common transmission route is needle-sharing among intravenous drug users. HCV infection can cause a short-lived illness characterized by tiredness and jaundice (yellow skin and eyes) but 70%–80% of newly infected people progress to a symptom-free, chronic infection that can eventually cause liver cirrhosis (scarring) and liver cancer. HCV infections can be treated with a combination of two drugs—pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin (PegIFN/R). However, PegIFN/R is expensive, causes unpleasant side-effects, and is ineffective in about half of people infected with HCV genotype 1, the commonest HCV strain.

Why Was This Study Done?

It would be extremely helpful to be able to identify which patients will respond to PegIFN/R before starting treatment. An individual's genetic make-up plays a key role in the safety and effectiveness of drugs. Thus, pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variants affects the body's response to drugs—has the potential to alter the clinical management of many diseases by allowing clinicians to provide individually tailored drug treatments. In 2009, scientists reported that certain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, a type of genetic variant) lying near the IL28B gene (which encodes an immune system protein made in response to viral infections) strongly influence treatment outcomes and spontaneous clearance in HCV-infected people. This discovery is now being used to predict treatment responses to PegIFN/R in clinical practice but genotyping (analysis of variants of) IL28B only correctly predicts treatment failure two-thirds of the time. Here, the researchers investigate whether genotyping two additional regions of the genome—the HLA-C and KIR gene loci—can improve the predictive value of IL28B genotyping. Human leukocyte antigen C (HLA-C) and the killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) are interacting proteins that have been implicated in HCV viral control.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find?

The researchers genotyped 417 patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 1 whose infection had been cleared by PegIFN/R treatment, 493 patients whose infection had not responded to treatment, and 234 patients whose infection had cleared spontaneously for two HLA-C variants (C1 and C2), the presence of several KIR genes (individuals carry different combinations of KIR genes), and two IL28B SNPs (rs8099917 and rs12979860). Carriage of “variants” of either IL28B SNP was associated with absence of treatment-induced clearance and absence of spontaneous clearance. That is, these variant SNPs were found more often in patients who did not respond to treatment than in those who did respond, and more often in patients who did not have spontaneous clearance of their infection than those who did. The HLA-C C2C2 genotype (there are two copies of most genes in the genome) was also more common in patients who failed treatment than in those who responded but was not associated with spontaneous clearance. The rate of correct prediction of treatment failure increased from 66% with IL28B genotyping alone to 80% with combined IL28B and HLA-C genotyping. Finally, carriage of specific KIR genes in combination with specific HLA-C and IL28B variants was also associated with an altered HCV treatment response.

What Do These Findings Mean?

These findings show that the addition of HCL-C and KIR genotyping to IL28B genotyping improved the prediction of HCV treatment response in the patients investigated in this study. Because all these patients were European or of European descent, these findings need confirming in people of other ethnic backgrounds. They also need confirming in other groups of Europeans before being used in a clinical setting. However, the discovery that the addition of HLA-C genotyping to IL28B genotyping raises the rate of correct prediction of PegIFN/R treatment failure to 80% is extremely promising and should improve the clinical management of patients infected with HCV genotype 1. In addition, these results provide new insights into how PegIFN/R clears HCV infections that may lead to improved therapies in the future.

Additional Information

Please access these websites via the online version of this summary at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001092.

- The World Health Organization provides detailed information about hepatitis C (in several languages)

- The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides information on hepatitis C for the public and for health professionals (information is also available in Spanish)

- The US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases provides basic information on hepatitis C (in English and Spanish)

- The Hepatitis C Trust is a patient-led, patient-run UK charity that provides detailed information about hepatitis C and support for patients and their families; a selection of personal stories about patients' experiences with hepatitis C is available, including Phil's treatment story, which details the ups and downs of treatment with PegIFN/R

- MedlinePlus provides links to further resources on hepatitis C

- The Human Genome Project provides information about medicine and the new genetics, including a primer on pharmacogenomics

Introduction

Studies of human genetics have been expected to alter clinical management for many diseases, including infectious diseases. Yet, to date, there are few examples of the use of such information in routine clinical practice. One of the most promising examples, identified in genome-wide analyses, is used to predict response to treatment for hepatitis C, based on a single genetic variant.

Only 20%–30% of the ∼170 million people infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) recover spontaneously; the remainder develop chronic infection [1] with a risk for developing cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma [2]. Current standard of care with pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin (PegIFN/R) achieves a sustained virological response (SVR) (HCV RNA undetectable 6 mo post cessation of therapy) in 40%–50% of those infected with the most common viral genotype, type 1, after 48 wk [3]. Treatment is expensive and is associated with numerous side effects, which sometimes require dose reduction and premature treatment cessation, thus increasing the risk of treatment failure. Host genotyping studies have the potential to identify genes and therefore pathogenic processes important in viral clearance, enabling a rational approach to design new drugs, and to identify patients who will most likely respond to current and new treatments.

We and others previously used genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify SNPs in the genetic region encoding IL28B, which strongly influences treatment outcome [4]–[6] and spontaneous clearance [7]. Other genes associated with drug response have not yet been identified in GWAS with genome-wide significance. Variants in linkage with IL28B allow prediction of up to 64% for failure to clear virus during therapy in cross-sectional cohorts [5]. The minor allele of SNP rs8099917 tags the nonresponse haplotype in Asians and Caucasians, but not in African Americans. The minor allele of SNP rs12979860 is on this haplotype in all ethnic groups, and on other less significant haplotypes, so is used where African Americans are in the patient cohort [8].

GWAS are dependent on SNPs tagging associated genetic variants and cannot measure interactions because of the high statistical penalty for multiple comparisons. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) are highly polymorphic genetic loci whose gene proteins interact with each other and for which proxy SNPs for their major variants have yet to be identified. HLA-C molecules present ligands for KIR2DL receptors, with a functionally relevant dimorphism determining KIR specificity: HLA-C group 1 (HLA-C1) alleles, identified by Ser77/Asp80 of the HLA-C alpha 1 domain, are ligands for the inhibitory receptors KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 and the activating receptor KIR2DS2 [9],[10]. HLA-C group 2 (HLA-C2) alleles, identified by Asp77/Lys80, are recognized by inhibitory KIR2DL1 and activating KIR2DS1 [9]–[12]. KIR2DL3 and its ligand, HLA-C1 has been associated with an increased likelihood of spontaneous [13]–[15], and treatment-induced HCV clearance [14],[15]. This association is attributed to differential natural killer (NK) cell activation and function in the context of this KIR/HLA interaction [16]. SNPs from the HLA-C coding regions showed weak associations with SVR in our original GWAS [5].

The current study specifically addresses whether the IL28B and KIR/HLA-C gene loci have separate, additive, or interactive effects on HCV clearance (spontaneous or treatment induced). This information is essential to better understand the role of IL28B during HCV infection, to better predict response to therapy, and potentially to allow better selection of patients for treatment.

Methods

Ethics Statement and Study Participants

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committees of Sydney West Area Health Service and the University of Sydney. All other sites had ethical approval from their respective ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Characteristics of each cohort are shown in Table 1. All treated patients were infected with genotype 1, received PegIFN/R, and had virological response determined 6 mo after completion of therapy. The diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) was based on appropriate serology and presence of HCV RNA. All SVRs and non-SVR cases received therapy for 48 wk except when HCV RNA was present with a <2 log drop in HCV RNA level after 12-wk therapy. Patients were excluded if they had been coinfected with either hepatitis B virus or HIV or if they were not of European descent.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for chronic hepatitis C patients after therapy, and for those participants with spontaneous virus clearance of HCV included in this study.

| Demographic Factorsa | Australian Cohort (n = 312) | Berlin Cohort (n = 310) | Newcastle, UK Cohort (n = 69) | Bonn Cohort (n = 57) | Trent, UK Cohort (n = 48) | Turin Cohort (n = 114) | Total Cohort (n = 910) | Participants with spontaneous virus clearance (n = 234) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVR (n = 130) | NSVR (n = 182) | SVR (n = 150) | NSVR (n = 160) | SVR (n = 31) | NSVR (n = 38) | SVR (n = 26) | NSVR (n = 31) | SVR (n = 22) | NSVR (n = 26) | SVR (n = 58) | NSVR (n = 56) | SVR (n = 417) | NSVR (n = 493) | ||

| Age (y) | 40.0 (9.6) | 44.5 (7.1) | 41.0 (10.5) | 46.7 (10.3) | 38.2 (11.8) | 46.0 (12.0) | 44.7 (12.9) | 50.8 (10.9) | 39.8 (9.8) | 45.7 (7.9) | 43.3 (13.1) | 45.1 (10.0) | 40.9 (10.8) | 45.7b (9.3) | NA |

| Gender (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Females | 52 (40.0) | 42b (23.1) | 79 (52.7) | 69 (43.1) | 9 (29.0) | 10 (26.3) | 11 (42.3) | 11 (35.5) | 6 (27.3) | 5 (19.2) | 28 (48.3) | 19 (33.9) | 185 (44.4) | 156b (31.6) | 111 (47.4) |

| Males | 78 (60.0) | 140 (76.9) | 71 (47.3) | 91 (55.9) | 22 (71.0) | 28 (73.7) | 15 (57.7) | 20 (64.5) | 16 (72.7) | 21 (80.8) | 30 (51.7) | 37 (66.1) | 232 (55.6) | 337 (68.4) | 123 (52.6) |

| BMI | 26.9 (5.1) | 27.4 (5.3) | 25.1 (4.5) | 25.9 (3.9) | 23.7 (6.3) | 26.2 (6.6) | 25.4 (4.2) | 27.3 (4.6) | 26.9 (3.5) | 25.0 (2.9) | 24.0 (3.2) | 24.5 (3.3) | 25.5 (4.7) | 26.3 (4.7) | NA |

| Viral loadc | NS | NS | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | NS | NS | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | p<0.05 | NA |

Samples from individuals with spontaneous clearance were collected from Westmead Hospital in Sydney (n = 149), the Melbourne NETWORK study (n = 31) [17], the Australian ATACH study (n = 18) [18], and Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitaet, Bonn, Germany (n = 36). Spontaneous clearance was defined as HCV RNA negative and hepatitis C antibody positive without undergoing hepatitis C treatment.

Genotyping

For HLA-C, samples were genotyped by multiplex PCR [19] to two-digit resolution. For samples from Turin and those participants with spontaneous virus clearance, HLA-C genotyping was by PCR and sequencing. All Australian samples were genotyped by multiplex PCR for KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 [20]. KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 in the remainder and in those participants with spontaneous virus clearance and KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2 in all samples were genotyped by PCR using the protocol of Ashouri et al. [21]. 2DL1 was not included owing to the fact that it is very common (>90%), so we would have insufficient power to detect an association with its absence. The rs8099917 SNP was genotyped as previously reported [5]. The IL28B rs12979860 SNP was genotyped using a custom made Taqman genotyping kit. Further details are reported in Text S1.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann-Whitney and chi-squared tests were used to analyze baseline covariates. A chi-squared test was used to examine differences in allele, carriage, and genotype frequencies between SVR versus non-SVR (NSVR), those participants with spontaneous virus clearance (SC) versus CHC (i.e., NSVR plus SVR), and viral clearance (SC plus SVR) versus NSVR. The relationships between HLA-C, IL28B, and the KIR loci were investigated using logistic regression for predicting failure of SVR. Significance of all models was assessed by likelihood ratio (LR) tests. Analysis was carried out in R (v2.12).

Results

IL28B Genotype and HCV Viral Clearance

We had previously shown that the IL28B rs8099917 G allele predicts failure to clear HCV on PegIFN/R therapy [5], in the CHC cohort now analysed here for HLA-C and KIR genotypes. Carriers of the G allele were under-represented in SC (odds ratio [OR] 0.26, p = 1.71×10−14, 2.67–5.48) (Tables 2 and S1). The G allele appears to have a dominant effect, with both heterozygotes (OR 3.42, p = 1.32×10−11, 2.36–4.96) and homozygotes (OR 3.25, p = 1.78×10−2, 1.16–9.10) being similarly more likely to fail to clear virus spontaneously. SNP rs8099917 G carriers were 19.7% of SC, 27.5% of healthy controls (HapMap CEU [Utah residents with Northern or Western European ancestry] data), 37.9% of SVR, and 57.3% of NSVR (Table S1). Overall, those who failed to clear the virus after therapy or without therapy (NSVR versus SVR and SC) were much less likely to have the rs8099917 TT genotype (OR 0.34, p = 1.44×10−17) (Table S1), with both heterozygotes (OR 2.59, p = 5.91×10−14) and homozygotes (OR 2.12, p = 7.54×10−3) for the G allele more likely to fail to clear virus.

Table 2. Association of IL28B rs8099917 and HLA-C genotypes with viral clearance on therapy and spontaneous clearance.

| Cohort | IL28 | HLA-C | IL28/HLA-Ca | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | TG | GG | C1C1 | C1C2 | C2C2 | C1*TT | C2C2 G* | |

| SVR ( n = 398/390/389) b | 247 (62.0) | 134 (33.7) | 17 (4.3) | 151 (38.7) | 185 (47.4) | 54 (13.8) | 200 (51.4) | 13 (3.3) |

| NSVR ( n = 475/463/459) b | 203 (42.7) | 239 (50.3) | 33 (6.9) | 180 (38.9) | 192 (41.5) | 91 (19.7) | 160 (34.9) | 53 (11.5) |

| p -Value | 1.27×10−8 | 7.35×10−7 | 0.090 | 1.0 | 0.084 | 0.024 | 1.17×10−6 | 8.83×10−6 |

| OR, 95% CI | 0.46, 0.35–0.60 | 2.0, 1.52–2.63 | 1.52, 1.05–2.20 | 0.51, 0.38–0.67 | 3.78, 2.03–7.04 | |||

| Participants with spontaneous virus clearance ( n = 218/228/212) a | 175 (80.3) | 39 (17.9) | 4 (1.8) | 95 (41.7) | 105 (46.1) | 28 (12.3) | 147 (69.3) | 2 (0.9) |

| CHC ( n = 873/853/848) c | 450 (51.5) | 373(42.7) | 50(5.7) | 331(38.8) | 377(44.2) | 145(17.0) | 360 (42.5) | 69 (6.5) |

| p -Value | 1.71×10−14 | 1.32×10−11 | 0.018 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.084 | 2.40×10−12 | 1.27×10−3 |

| OR, 95% CI | 0.26, 0.18–0.37 | 3.42, 2.36–4.96 | 3.25, 1.16–9.10 | 0.33, 0.24–0.45 | 7.31, 1.78–30.06 |

HLA-C2C2 Predicts Poor Viral Clearance on Therapy

The HLA-C1 and C2 variants are associated with a number of aspects of viral clearance. HLA-C2 homozygotes were more likely to fail to clear virus on therapy than other genotypes (OR 1.52, p = 0.025, 1.05–2.20) (Figure 1; Table 2). The HLA-C effect on viral clearance seems to be a recessive trait, such that C1 heterozygotes are no more susceptible to treatment failure than C1 homozygotes. HLA-C2 homozygosity was not different between those participants with spontaneous virus clearance and healthy European controls (data for healthy controls from [22],[23]) (see Table S2). This important observation suggests that the difference in association of HLA-C genotype with viral clearance is due to response to therapy alone, not to the immune response in the absence of therapy. From two-digit genotyping of HLA-C, the C2 variant conferring highest susceptibility to treatment failure is Cw*05 (OR 1.43, p = 0.047, 1.0–2.03) (Table S3). The Cw*03 variant of C1 confers significant drug response (OR 0.61, p = 1.64×10−3, 0.44–0.83).

Figure 1. Association of HLA-C genotype with viral clearance with and without therapy.

OR is plotted against viral clearance for each comparison, plus or minus 95% confidence interval (CI). Vertical height of plotted points is in proportion to log (1/p) where “_p_” is the probability of observed association being by chance. ORs are shown for each comparison. G*, carrier of G allele.

Effect of KIR Genes on Viral Clearance

We tested if KIR2DL2 or 2DL3 affected response to therapy, protection against development of CHC, or clearance of virus with or without PegIFN/R (Table S4). As reported by others [13],[14], we observed no effect of KIR genotype per se on viral clearance in any comparison. There was evidence of a similar trend between homozygosity of HLA-C1 and KIR2DL3 with SVR [14], and with spontaneous clearance [13]. Consistent with Knapp et al. [14] and Khakoo et al. [13], we found evidence that those infected with HCV and with the KIR2DL3/C2C2 genotype, were more likely to fail to clear virus (OR 1.91, p = 0.022, 1.09–3.36) (Table S5) on therapy (NSVR versus SVR), and more common in those who failed to clear virus on therapy (NSVR) compared to those who did combined with those who cleared HCV without therapy (SVR+SC) (OR 2.08, p = 3.00×10−3, 1.27–3.40).

We next tested the combination of HLA-C alleles with KIR2DL3 and 2DL2 genes (Table S6). There was evidence of increased association with the complementary pairs, so that the combination of the C1 variant Cw*03 with its inhibiting genes was associated with increased treatment response: Cw*03 alone OR is 0.61 (p = 1.64×10−3, 0.44–0.83), with 2DL2 is 0.47 (p = 1.19×10−3, 0.29–0.75), with 2DL3 is 0.49 (p = 2.13×10−4, 0.33–0.72). Most of the C2 association with treatment failure was due to allele Cw*05 (OR 1.43, p = 4.66×10−2, 1.0–2.03), with a larger effect in combination with the inactivating haplotype tagged by 2DL3 (OR 1.97, p = 2.04×10−3, 1.28–3.06), but unaffected by 2DL2.

Effect of Activating KIR Genes on Viral Clearance

The KIR ligands on NK cells activated on ligation to HLA-C are KIR2DS2 for HLA-C1, and KIR2DS1 for HLA-C2. Increased activation could occur in HLA-C1 carriers who are also carriers of KIR2DS2, and for HLA-C2 carriers who are also carriers of KIR2DS1. However, we found no evidence that KIR2DS genotypes affected viral clearance either singly or in combination with HLA-C genotypes (Tables S7 and S8), although from a logistic regression model, it seems that KIR2DS1 could mitigate the effect of HLA-C2C2 (see below).

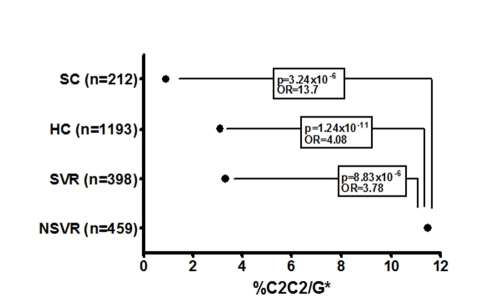

Combined Effect of HLA-C and IL28B Genotypes

Prediction of failure to clear HCV in response to treatment with either IL28B or HLA-C genotypes alone is of limited value clinically due to the relatively low positive predictive value (PPV) for treatment failure [24]. We therefore tested if both genotypes together provided additional power to predict response. Indeed, the combination significantly improves prediction of failure to clear virus on therapy (OR 3.78, p = 8.83×10−6, 2.03–7.04), failure to clear virus spontaneously (OR 7.31, p = 1.27×10−3, 1.78–30.06), and failure to clear virus with and without therapy (OR 5.10, p = 2.53×10−9, 2.84–9.17) (Tables 2 and S9a). The largest difference was between those participants with spontaneous virus clearance and those who failed to clear virus on therapy (Figure 2). As shown in Table 3, prediction of treatment failure improved from 66% for IL28B G to 80% with IL28B G*/C2C2.

Figure 2. Proportion of each cohort with the HLA-C2C2 and IL28B G* genotype, which predicts treatment failure.

HC, healthy controls; G*, carrier of G allele. Lines connect the significant 2×2 chi-squared comparisons with associated _p_-values and ORs. HC numbers obtained from Williams et al. [23] and Dunne et al. [22].

Table 3. Prediction of failure to clear virus on therapy with PegIFN/R.

| Genotype | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL28GG | 7 | 96 | 66 | 46 |

| IL28G* | 57 | 62 | 64 | 55 |

| HLA-C2C2 | 20 | 86 | 63 | 47 |

| HLA C2* | 61 | 39 | 54 | 46 |

| IL28G*/HLA-C2C2 | 12 | 97 | 80 | 48 |

A similar predictive value for treatment response has been reported for IL28B SNP rs12979860[4] We found that the PPV derived from combining this SNP and HLA-C2C2 was actually lower in this cohort than for the rs8099917 combination (OR 2.52, p = 5.18×10−5, 1.59–3.98) (Table S9b). Adding the clinical features of age, gender, body mass index, or viral load improved predictive value (Figure S1, responder operator curves).

Interactions between IL28B, HLA-C, and KIR

Using a logistic regression model, the increased OR of 3.78 for the combination rs8099917, G*/C2C2 is partially due to genetic interaction (LR, p<0.05) (Table S10), and not just an additive effect. Examining the relationship between KIR genotype and either HLA-C2C2 or IL28B rs8099917 G*, we found no evidence for any two-way interactions for predicting failure of SVR. For the three-way interaction model between HLA-C, IL28, and not 2DS1, although the coefficient for the three-way interaction is significant, the LR test concludes that the model does not produce a significantly better fit (LR, p = 0.28). Although the HLA-C main effect is not significant via a standard _t_-test in the interaction model, it is associated with response (Table 2). Adding HLA-C to a model including rs8099917 leads to significant improvement of the fit (LR, p = 0.006), implying that HLA-C has an independent affect on response and should be included in the model. Adding the interaction term again improves the model fit (LR, p = 0.03).

Discussion

The IL28B genotype is already used to predict treatment response to PegIFN/R in clinical practice, even though its association with therapeutic response was only first identified in late 2009. We tested the IL28B, HLA-C, and KIR gene variant associations with treatment-induced and spontaneous clearance of HCV and confirmed that IL28B rs8099917 predicts clearance in both situations. The HLA-C2C2 genotype predicted failure to clear HCV on treatment, but no association with failure to clear HCV without treatment was detected. The prediction of treatment-induced clearance was additive and interactive between IL28B and HLA-C; and there was evidence of additive and interactive effects between KIR2DL3, KIR2DS1, and HLA-C2C2. These data and previous reports point to HLA-C as being the second gene predicting PegIFN/R treatment response in HCV. This genetic evidence supports an underlying physiological mechanism for HCV viral control involving an interaction between IL28B, HLA-C, and _KIR_s.

Khakoo et al. [13] and Dring et al. [25] compared HLA-C and KIR genotypes between those participants with spontaneous virus clearance and CHC, and Knapp et al. [14] in these and in treatment response. As in our study, Khakoo et al. reported HLA-C2 homozygotes were more common in CHC than SC (OR 1.49, p = 0.02), and KIR2DL3-C2 homozygotes slightly more so (OR 1.87, p = 0.01); and Dring et al. reported KIR2DS3-C2 carriers were more common in CHC than SC (OR 2.26, p = 0.002). Knapp et al. detected a trend towards C2 excess in those who failed to clear virus spontaneously compared to CHC (OR 1.69, p = 0.10), a trend of C2 excess in NSVR versus SVR (OR 1.38, p = 0.27) [13], but no difference between SVR and SC. In both the Knapp study and ours, the KIR2DL3-C1 homozygotes were more common in SVR, and most of this association was due to the C1-Cw*03 variant. KIR2DL3 tags haplotype A, which contains fewer activating KIR genes. This association is consistent with insufficient activation of NK cells in the context of HLA-C2C2 inhibition as the basis for increased risk of treatment failure.

Dring et al. [25] identified a dramatic synergy between KIR2DS3 (not examined here, encoded on haplotype B) and the IL28B SNP rs12979860 in predicting spontaneous clearance in a unusually homogenous cohort of Irish females infected with genotype 1 HCV by transfusion. They also showed that IFNλ inhibited IFNγ production by NK cells. They did not examine SNP rs8099917 or SVR and NSVR. Their data further support NK function in HCV clearance as being influenced by IFNλ.

Because of the very high linkage disequilibrium in the MHC class I region around HLA-C, the association we and others have observed may be due to HLA-C variants tagging other class I genes. However, the KIR interactions, which are HLA-C specific, support the signal being due to HLA-C itself, as does the strong body of evidence pointing to the importance of NK cells in killing virally infected cells in response to interferon and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (reviewed in [26]–[28]). In addition, activated NK cells recognize and lyse HCV replicon-containing hepatoma cells in vitro [27] and should therefore be able to kill virus-infected hepatocytes in vivo. Cells that lack or have downregulated MHC class I molecules, such as virally infected cells or tumour cells, are susceptible to NK cell-mediated killing. In this context it has been reported that IFNλ3 (the protein encoded by IL28B) augments the antitumor activity of NK cells [11],[27].

The association of HLA-C with viral clearance on treatment but not spontaneous clearance suggests that, on therapy, NK killing of hepatocytes is augmented in HLA-C1 carriers compared to C2 homozygotes. There are numerous potential mechanisms by which HLA-C genotypes could affect NK cell activity in the context of IFNα treatment. IFNα could affect NK killing of HCV-infected hepatocytes. IFNα is known to increase NK sensitivity to activation [27], but also to directly activate NK cells in patients with HCV infection and induced a strongly cytotoxic phenotype [27]. This NK cell activation and killing of hepatocytes is affected by the HLA-C genotype: the C1 allele allowing activation more rapidly and aggressively [16]. HLA-C may be even more upregulated in response to IFNα [29], making it more difficult for C2 homozygotes to activate NK cells.

The association of IL28B genotype with SC and therapeutic response indicates that IFNλ3 affects viral clearance. IFNλ3 is likely to enhance antiviral mechanisms through upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in acute disease [24], but its effect may be more complicated in chronic infection, in which upregulation of ISGs in liver is associated with reduced treatment response [30]. One approach to identifying the molecular pathways through which a genetic variant affects disease outcome is to identify other genes that affect pathogenesis, and especially those with which it may interact. The additive association of HLA-C and IL28B genotypes with treatment-induced clearance, but not spontaneous clearance, suggests IL28B may be enhancing NK killing on PegIFN/R therapy. HLA-C is one of the most upregulated genes following treatment of a cell line with IFNλ3 [29]. The degree of this upregulation may depend on HLA-C genotype.

The larger predictive value for HLA-C2C2 and IL28B rs8099917 G* than SNP rs12979860 T* may indicate different haplotype effects. There are five common IL28B haplotypes in Caucasians [5]. The rs8099917 minor allele tags the haplotype with the highest association with therapeutic response, whilst rs12979860 minor alleles are on this haplotype and others (Table S11). Ge et al. [4] reported that there was evidence of independent effects of the two haplotypes. Therefore the additive effect of HLA-C with IL28B may be only with the rs8099917-tagged haplotype. It is likely that these two SNPs, which were on genotyping chips, will be supplanted by others when a more comprehensive analysis of the genetic variation of IL28B is available.

The overall differences in frequency of HLA-C2C2/IL28B G* in healthy controls, those participants with spontaneous virus clearance, SVR, and NSVR groups suggests a role in pathogenesis for this gene combination. It is also striking that HLA-C2C2 frequency is highly variable between ethnic groups, roughly in proportion to their treatment responsiveness (Figure S2). Much of the variation between African Americans and European Americans has been explained by the IL28B rs12979860 SNP [4], but it seems likely that the higher proportion of the HLA-C2C2 genotype in African Americans may also contribute to their reduced viral clearance.

With regard to patient management, avoiding treatment in those less likely to respond to PegIFN/R is important given the toxicity of this treatment and the likelihood that one or multiple direct acting antiviral agents will soon be available [31],[32]. In this context, IL28B genotype alone allows prediction of failure of PegIFN/R in only 66% of patients (Table 3). We have shown that with HLA-C genotyping this can be improved to a clinically more meaningful 80%. Genotyping of IL28B and HLA-C to C1/C2 is rapid and inexpensive. Further genetic associations, including those affecting HLA-C/IFNλ interactions, viral sequence variability [33], and host/virus interactions such as IP-10 levels [34] might further enhance prediction of treatment outcomes.

In addition to supporting the importance of HLA-C, KIR, and IL28B in HCV clearance and drug response, and emphasizing the role of NK cells in the outcomes of HCV infection, this study highlights the value of investigating variants other than SNPs to identify genetic variants causing disease and drug response. Notably, independent replication of these data in Europeans, and testing them for the first time in African-Americans and other ethnic groups is required.

Supporting Information

Figure S1

Responder operator curves for prediction of failure to clear virus on therapy based on clinical and genotyping data.

(DOC)

Figure S2

Proportion of each ethnic group with the genotype that predicts treatment failure: HLA-C2C2 homozygotes and IL28B G carriers.

(DOC)

Table S1

Association of IL28B rs8099917 genotypes with viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S2

Comparison of HLA-C group 1 and 2 allele and genotype distribution from previous studies.

(DOC)

Table S3

HLA-C (two-digit genotyping) in SVR and NSVR.

(DOC)

Table S4

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S5

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance with and without therapy in combination with HLA-C genotypes.

(DOC)

Table S6

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance in combination with HLA-C genotypes based on two-digit genotyping.

(DOC)

Table S7

Association of HLA-C activating receptor genes KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2 on viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S8

Association of HLA-C activating receptor genes KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2 on viral clearance with and without therapy in combination with HLA-C genotypes.

(DOC)

Table S9

(a) Association of combinations of IL28B SNP rs8099917 and HLA-C genotypes on viral clearance with and without therapy. (b) Association of combinations of IL28B SNP rs12979860 and HLA-C genotypes on viral clearance with therapy.

(DOC)

Table S10

Odds ratios and corresponding _p_-values for predicting failure of SVR using logistic regression models.

(DOC)

Table S11

The distribution of the six common IL28B haplotypes bound by SNPs rs12980275 and rs8099917.

(DOC)

Text S1

Supplementary methods.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all patients for their valuable participation in this study. The IHCGC team includes Monika Michalk from University of Bonn; Barbara Malik from Universitätsmedizin Berlin; Patrick McClure and Sherie Smith from the University of Nottingham; Elizabeth Snape and Vincenzo Fragomeli from Nepean Hospital; Richard Norris and Dianne How-Chow from St Vincent's Hospital; Julie R. Jonsson and Helen Barrie from Princess Alexandra Hospital; Sacha Stelzer-Braid and Shona Fletcher from Prince of Wales Hospital; Tanya Applegate and Jason Grebely from the National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research and Mandvi Bharadwaj from the Burnet Institute. We would also like to thank Reynold Leung for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

CHC

chronic hepatitis C

GWAS

genome-wide association study

HCV

hepatitis C virus

HLA-C

human leukocyte antigen C

IL28B

interleukin 28B

KIR

killer immunoglobulin-like receptors

LR

likelihood ratio

NK

natural killer

NSVR

no sustained viral response

OR

odds ratio

PegIFN/R

pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin

SC

spontaneous clearer

SVR

sustained viral response

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

VS, DB, GS, and JG were supported by Australian Research Council Roche Linkage Project grant LPO0990067 and the Robert W. Storr Bequest to the Sydney Clinical School, University of Sydney. GD is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship. TB is supported by the German Competence Network for Viral Hepatitis (Hep-Net), funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Grant No. 01 KI 0437, Genetic host factors in viral hepatitis and Genetic Epidemiology Group in viral hepatitis) and by the EU-Vigilance network of excellence combating viral resistance (VIRGIL, Projekt No. LSHM-CT-2004-503359) as well as by the BMBF Project: Host and viral determinants for susceptibility and resistance to hepatitis C virus infection (Grant No. 01KI0787, Project B). DS and MB (Newcastle University, UK) are funded by a Medical Research Council UK project grant G0502028. JN was supported by BMBF (German Ministry for Science and Education) [grant no. 01KI0791] and H.W. and J. Hector Foundation [grant no. M42]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S21–S29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967–972. doi: 10.1038/nature04082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399–401. doi: 10.1038/nature08309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/ng.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/ng.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afdhal NH, McHutchison JG, Zeuzem S, Mangia A, Pawlotsky JM, et al. Hepatitis C pharmacogenetics: state of the art in 2010. Hepatology. 2011;53:336–345. doi: 10.1002/hep.24052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colonna M, Borsellino G, Falco M, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL. HLA-C is the inhibitory ligand that determines dominant resistance to lysis by NK1- and NK2-specific natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:12000–12004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Winter CC, Peruzzi M, Long EO. Killer cell inhibitory receptors specific for HLA-C and HLA-B identified by direct binding and by functional transfer. Immunity. 1995;3:801–809. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Numasaki M, Tagawa M, Iwata F, Suzuki T, Nakamura A, et al. IL-28 elicits antitumor responses against murine fibrosarcoma. J Immunol. 2007;178:5086–5098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato A, Ohtsuki M, Hata M, Kobayashi E, Murakami T. Antitumor activity of IFN-lambda in murine tumor models. J Immunol. 2006;176:7686–7694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khakoo SI, Thio CL, Martin MP, Brooks CR, Gao X, et al. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2004;305:872–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1097670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knapp S, Warshow U, Hegazy D, Brackenbury L, Guha IN, et al. Consistent beneficial effects of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 2DL3 and group 1 human leukocyte antigen-C following exposure to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2010;51:1168–1175. doi: 10.1002/hep.23477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidal-Castineira JR, Lopez-Vazquez A, Diaz-Pena R, Alonso-Arias R, Martinez-Borra J, et al. Effect of killer immunoglobulin-like receptors in the response to combined treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2009;84:475–481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01285-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlenstiel G, Martin MP, Gao X, Carrington M, Rehermann B. Distinct KIR/HLA compound genotypes affect the kinetics of human antiviral natural killer cell responses. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1017–1026. doi: 10.1172/JCI32400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dore GJ, Hellard M, Matthews GV, Grebely J, Haber PS, et al. Effective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:123–135 e121–122. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aitken CK, Lewis J, Tracy SL, Spelman T, Bowden DS, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection in a cohort of injecting drug users. Hepatology. 2008;48:1746–1752. doi: 10.1002/hep.22534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witt CS, Price P, Kaur G, Cheong K, Kanga U, et al. Common HLA-B8-DR3 haplotype in Northern India is different from that found in Europe. Tissue Antigens. 2002;60:474–480. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni S, Martin MP, Carrington M. KIR genotyping by multiplex PCR-SSP. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;612:365–375. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-362-6_25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashouri E, Ghaderi A, Reed EF, Rajalingam R. A novel duplex SSP-PCR typing method for KIR gene profiling. Tissue Antigens. 2009;74:62–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunne C, Crowley J, Hagan R, Rooney G, Lawlor E. HLA-A, B, Cw, DRB1, DQB1 and DPB1 alleles and haplotypes in the genetically homogenous Irish population. Int J Immunogenet. 2008;35:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2008.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams F, Meenagh A, Patterson C, Middleton D. Molecular diversity of the HLA-C gene identified in a caucasian population. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:602–613. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahlenstiel G, Booth DR, George J. IL28B in hepatitis C virus infection: translating pharmacogenomics into clinical practice. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:903–910. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dring MM, Morrison MH, McSharry BP, Guinan KJ, Hagan R, et al. Innate immune genes synergize to predict increased risk of chronic disease in hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5736–5741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016358108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahlenstiel G, Titerence RH, Koh C, Edlich B, Feld JJ, et al. Natural killer cells are polarized toward cytotoxicity in chronic hepatitis C in an interferon-alfa-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:325–335 e321–322. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SH, Miyagi T, Biron CA. Keeping NK cells in highly regulated antiviral warfare. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stegmann KA, Bjorkstrom NK, Veber H, Ciesek S, Riese P, et al. Interferon-alpha-induced TRAIL on natural killer cells is associated with control of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1885–1897. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcello T, Grakoui A, Barba-Spaeth G, Machlin ES, Kotenko SV, et al. Interferons alpha and lambda inhibit hepatitis C virus replication with distinct signal transduction and gene regulation kinetics. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1887–1898. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honda M, Sakai A, Yamashita T, Nakamoto Y, Mizukoshi E, et al. Hepatic ISG expression is associated with genetic variation in interleukin 28B and the outcome of IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:499–509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, et al. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:705–716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60934-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, et al. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, et al. Amino acid substitution in hepatitis C virus core region and genetic variation near the interleukin 28B gene predict viral response to telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2010;52:421–429. doi: 10.1002/hep.23690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Askarieh G, Alsio A, Pugnale P, Negro F, Ferrari C, et al. Systemic and intrahepatic interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 kDa predicts the first-phase decline in hepatitis C virus RNA and overall viral response to therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2010;51:1523–1530. doi: 10.1002/hep.23509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Responder operator curves for prediction of failure to clear virus on therapy based on clinical and genotyping data.

(DOC)

Figure S2

Proportion of each ethnic group with the genotype that predicts treatment failure: HLA-C2C2 homozygotes and IL28B G carriers.

(DOC)

Table S1

Association of IL28B rs8099917 genotypes with viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S2

Comparison of HLA-C group 1 and 2 allele and genotype distribution from previous studies.

(DOC)

Table S3

HLA-C (two-digit genotyping) in SVR and NSVR.

(DOC)

Table S4

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S5

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance with and without therapy in combination with HLA-C genotypes.

(DOC)

Table S6

Association of HLA-C inhibitory receptor genes KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 on viral clearance in combination with HLA-C genotypes based on two-digit genotyping.

(DOC)

Table S7

Association of HLA-C activating receptor genes KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2 on viral clearance with and without therapy.

(DOC)

Table S8

Association of HLA-C activating receptor genes KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2 on viral clearance with and without therapy in combination with HLA-C genotypes.

(DOC)

Table S9

(a) Association of combinations of IL28B SNP rs8099917 and HLA-C genotypes on viral clearance with and without therapy. (b) Association of combinations of IL28B SNP rs12979860 and HLA-C genotypes on viral clearance with therapy.

(DOC)

Table S10

Odds ratios and corresponding _p_-values for predicting failure of SVR using logistic regression models.

(DOC)

Table S11

The distribution of the six common IL28B haplotypes bound by SNPs rs12980275 and rs8099917.

(DOC)

Text S1

Supplementary methods.

(DOC)