Interleukin-6 as a therapeutic target in human ovarian cancer (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Mar 15.

Abstract

Purpose

We investigated whether inhibition of IL-6 has therapeutic activity in ovarian cancer via abrogation of a tumor-promoting cytokine network.

Experimental Design

We combined pre-clinical and in silico experiments with a phase II clinical trial of the anti-IL-6 antibody siltuximab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer.

Results

Automated immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays from 221 ovarian cancer cases demonstrated that intensity of IL-6 staining in malignant cells significantly associated with poor prognosis. Treatment of ovarian cancer cells with siltuximab reduced constitutive cytokine and chemokine production and also inhibited IL-6 signalling, tumor growth, the tumor-associated macrophage infiltrate and angiogenesis in IL-6-producing intraperitoneal ovarian cancer xenografts. In the clinical trial, the primary endpoint was response rate as assessed by combined RECIST and CA125 criteria. One patient of eighteen evaluable had a partial response, whilst seven others had periods of disease stabilization. In patients treated for six months, there was a significant decline in plasma levels of IL-6-regulated CCL2, CXCL12 and VEGF. Gene expression levels of factors that were reduced by siltuximab treatment in the patients significantly correlated with high IL-6 pathway gene expression and macrophage markers in microarray analyses of ovarian cancer biopsies.

Conclusions

IL-6 stimulates inflammatory cytokine production, tumor angiogenesis and the tumor macrophage infiltrate in ovarian cancer and these actions can be inhibited by a neutralising anti-IL-6 antibody in pre-clinical and clinical studies.

Keywords: Interleukin-6, ovarian cancer, siltuximab, angiogenesis, macrophage

Introduction

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has tumor-promoting actions on both malignant and stromal cells in a range of experimental cancer models (1-5). It also is a downstream effector of oncogenic ras (6) and has been implicated as an important part of the cytokine network in several human cancers, including serous and clear cell ovarian cancer (7, 8), multiple myeloma (9), Castleman’s disease (10) and hepatocellular carcinoma (11).

In ovarian cancer, there is pre-clinical evidence that IL-6 enhances tumor cell survival and increases resistance to chemotherapy via JAK/STAT signalling in tumor cells (12) and IL-6 receptor alpha transignalling on tumor endothelial cells (13). In addition, IL-6 has pro-angiogenic properties (14), as well as regulating immune cell infiltration, stromal reaction and the tumor-promoting actions of Th17 lymphocytes (15). In patients with advanced disease, high plasma levels of IL-6 correlate with poor prognosis (16, 17), and elevated levels are also present in malignant ascites (18). Some ovarian cancer cell lines constitutively secrete IL-6, and its production is enhanced when these cells are co-cultured with other cells from the ovarian cancer microenvironment (7, 19, 20). We have found that this IL-6 is part of a malignant cell autocrine cytokine network in ovarian cancer cells (7). This network involves co-regulation of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, CCL2, CXCL12 and VEGF and has paracrine actions on angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment.

Collectively, these data led to us to the hypothesis that IL-6 antagonists may have therapeutic activity in patients with ovarian cancer via inhibition of a tumor-promoting cytokine network. To investigate this hypothesis, we studied IL-6 and IL-6 receptor expression in ovarian cancer biopsies and assessed activity of the anti-human-IL-6 antibody siltuximab (CNTO328) in tissue culture studies and human ovarian cancer xenografts. We also used bioinformatic analysis of IL-6 signalling pathways in ovarian cancer biopsies to validate further our observations on the role of IL-6 in ovarian cancer and mechanisms of action of action of anti-IL-6 antibodies. These experiments led us to conduct a single arm phase II clinical trial of siltuximab in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that was combined with pharmacodynamic analysis of IL-6-regulated cytokines in samples obtained during the trial.

We conclude that an anti-IL-6 antibody inhibits cytokine production, angiogenesis and macrophage infiltration, and that IL-6 may be a therapeutic target in women with advanced ovarian cancer.

Methods

Ethics statement

The phase II trial of siltuximab was approved by the appropriate UK regulatory authorities (MHRA reference 21313/0007; National Research Ethics Service reference 07/Q2803/30) and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were approved by the local ethics review process of the Biological Services Unit, Queen Mary University of London and conducted according to the UKCCCR guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research (21).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections of diagnostic biopsies obtained from trial patients, tumor sections in the xenograft models and tissue microarrays were stained with antibodies for IL-6 (Santa Cruz, sc-7920), CD68 (Dako, IR609), F4/80 (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK; MCA497R), gp80 (Santa Cruz, sc-661), gp130 (Abcam, ab59389), Jagged-1 (R&D Systems, AF1277), Ki67 (Dako, M7240) and Tyr705 phospho-STAT3 (Cell Signaling, 9145). Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin. Frozen tumor sections were used for Ki67 and F4/80 immunohistochemistry in tumors from the TOV21G xenograft model. Negative controls of identical tissue sections were used whereby the primary antibody was omitted. The conditions used for staining with individual antibodies were in accord with manufacturers recommendations. In relation to the IL-6 staining, antigen retrieval was carried out in citrate buffer (Vector). IL-6 expression (Santa Cruz sc-790, 1:50 dilution) was localised with diaminobenzidine.

Tissue Microarray and Automated analysis of Immunohistochemistry

Seventy-six paraffin-embedded tumor specimens from a previously described cohort (22) were used for tissue microarray (TMA) construction as previously described (23). The TMA was constructed using a manual tissue arrayer (MTA-1, Beecher Inc, WI) and consisted of four cores per patient. Two 1.0 mm cores were extracted from each donor block and assembled in a recipient block. 2 cores were taken from 2 different blocks for each tumor. There was an excellent correlation between cores (Spearmans Rho 0.88, p < 0.001 for IL6), suggesting no difference between blocks. Recipient blocks were limited to approximately 100 cores each.

A second prospectively collected cohort of 154 ovarian cancer patients was used for validation (24). The Aperio ScanScope XT Slide Scanner (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) system was used to capture whole slide digital images with a 20X objective. TMA slides were de-arrayed to visualize individual cores, using Spectrum (Aperio). Genie™ histology pattern recognition software (Aperio) was used to identify tumor from stroma in individual cores and a colour deconvolution algorithm (Aperio) was used to quantify tumor-specific and stromal expression of IL-6, gp80 and gp130. For full-face sections, a region of interest was manually selected at low power (5x), 20 random high power fields (HPF) were then generated using R software (www.r-project.org). 10 high power fields were then selected for analysis based on the quantity of tumor within the HPF and the absence of necrotic tissue and staining artefact. The output for the algorithm was intensity (measured on a scaled of 0-255) and positivity (measured as the number of positive pixels/mm2), which were combined to produce a tumor and stromal autoscore. Mean values were used for all tumors.

Cell culture

All glassware used for cell culture was baked at 220°C for 12 hours to remove contaminating endotoxin. All medium and culture reagents were prepared at Cancer Research UK Clare Hall, South Mimms, UK. Ovarian cancer cells lines (25) were grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2 in either endotoxin-free RPMI medium (IGROV-1, TOV11D and TOV21G) or endotoxin-free DMEM medium (SKOV-3) supplemented with 10% FBS (Autogen Bioclear, Calne, Wiltshire, UK) and passaged twice weekly. Cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma infection and authenticated using 16 loci short tandem repeat verification (LGC Standards, London, UK).

Siltuximab treatment of cells

After overnight culture, cells were fed with medium containing siltuximab or isotype control IgG at 10, 25, 50 and 100 μg/ml in triplicate. Cells were re-fed with the appropriate antibody on days 4 and 7, and counted using a Vi-cell cell counter (Beckman Coulter) on days 4, 7 and 11 after typsinisation and resuspension in 300 μl RPMI. Supernatants were collected on day 4 for cytokine analysis using MSD® and ELISA assays (see below).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates (15μg) were electrophoresed on an SDS 10% acrylamide gel and transferred to a nylon membrane. The membrane was blocked overnight (4°C in PBS with 0.1% Tween and 10% milk powder) and probed using anti-Jagged1 (R&D Systems, AF1277) or pSTAT3 (Cell Signaling, D3A7) antibodies. A horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used for detection (1:5,000, room temperature, 1 hour). Antibody binding was detected using the Western Lighting Chemiluminescence kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Science, Beaconsfield, United Kingdom). Protein concentration equivalence was confirmed after probing with anti-β-actin antibody.

Flow cytometry

Cells were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 2% heat inactivated FBS and 0.01% NaN3 and incubated for 40 min on ice with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies against the trans-membrane IL-6 receptors gp80 (BD Pharmingen; 551850), gp130 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-9994 PE) or isotype-matched control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2866) at 40-200 μg/ml. Cells were washed and analysed by flow cytometry on a FACScan® flow cytometer using Cellquest software (BD Pharmingen).

Growth of tumors in mice and bioluminescence imaging

5 × 106 luciferase-expressing IGROV-1-luc, TOV21G-luc or TOV112D-luc cells were injected ip into 20g 6-8 week old female BALB/c nu/nu mice. These cell lines were generated as previously published (7). Mice were observed daily for tumor growth and killed if peritoneal swelling reached UK Home Office limits (20% increase in abdominal girth). Mice were injected i.p. with 150μg/g d-luciferin in 100 μl PBS and imaged as previously described (7).

Quantification of tumor blood vessels

To visualise the architecture of blood vessels, animals were anaesthetised and injected with FITC-conjugated Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (tomato lectin; 100μl, 2 mg/ml; Vector Laboratories) via the tail vein 3 min before animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde under terminal anaesthesia. Samples were processed and microvessel density was analysed as outlined in (7).

Serum processing and cytokine analysis in mouse models

100μl blood was taken from all mice via the tail vein prior to and 2 and 4 weeks after tumor cell injection. Samples were aliquoted and stored on ice for 1-2hr prior to centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Serum was then snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Cytokine analyses with ECL assays were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (MSD® human IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8 and VEGF multi-plex microplate, N45CA-1; MSD® murine IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ and VEGF, N45IB-1).

Patients and siltuximab administration

Between August 2007 and January 2009, twenty patients, median age 62.5 years, with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, defined as radiological and/or CA125 progression within six months of prior platinum-based chemotherapy, were recruited into this open label phase 2 study. Two patients progressed rapidly following consent with symptomatic small bowel obstruction and did not receive any treatment. Patients were deemed evaluable if they received one dose of siltuximab, thus 18 were evaluable. Patients were required to have adequate bone marrow and organ function and a World Health Organisation (WHO) performance status of 0 - 2. Patients could not have had more than three prior platinum-containing treatment regimens. Of the 18 evaluable patients, 9 (50%) had received two prior lines of chemotherapy, whilst 6 (33%) had received three or more lines. Of the 18, 7 had received prior single agent liposomal doxorubicin for platinum-resistant disease. Seventeen of the evaluable patients had disease that was measureable by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria, whereas one had raised CA125 only. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are found in Supplementary Table 1 and patient characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

The trial was funded by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council and sponsored and monitored by Queen Mary University of London. Each patient provided written informed consent. The trial was registered with the European Union Clinical Trials database (EudraCT, reference 2006-005704-13). The trial was subject to a MHRA inspection in November 2008 with no critical findings. Orthobiotech Oncology supplied silituximab at no cost.

Each cycle of treatment involved an infusion of siltuximab at 5.4mg/kg (ideal body weight) every two weeks. This dosing schedule was chosen as it had been shown in previous studies to supress CRP concentrations below the lower limit of quantification, and was also used in phase I studies siltuximab and pharmacokinetic modelling in other malignancies (26, 27). The primary endpoint was the response rate to siltuximab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, whilst the secondary endpoints were changes in IL-6 and IL-6 related cytokines in response to siltuximab treatment, and Quality of Life, as assessed by EORTC QLQ-C30 and OV-28 questionnaires. Toxicity was assessed prior to each siltuximab infusion and reported using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3. Disease was assessed by CT scan after three (12 patients) or five (6 patients) treatments and every 12 weeks thereafter, and by CA125 measurement, performed every two weeks. Best overall response was defined by combined RECIST/CA125 criteria [19]. In addition, 14 patients also had [18F] FDG-PET imaging with their CT scans, which was analysed as previously described (28).

Blood sample collection from patients

Blood was taken prior to each cycle of treatment for haematological and biochemical indices, CRP and β2-microglobulin. During the first three treatments, blood was also taken on day 8 after each infusion. Blood was also taken prior to and 1 hr after each cycle of treatment and subsequently processed for plasma cytokine and chemokine analysis. Sampling was performed 24 hours and one week after each of the first three infusions. All blood specimens were collected and handled by suitably trained, competent individuals. All samples were processed according to standard operating procedures and logged accordingly. In addition, freezer temperatures were monitored and logged on a daily basis.

10 ml of blood was withdrawn from each patient and transferred into a 15 ml sterile, pyrogen free falcon tube (BD Falcon) containing 300 units of heparin (CP Pharmaceuticals). The tubes were inverted gently several times to ensure thorough mixing, kept on wet ice and processed within 1 hour of collection by centrifugation at 3100 rpm or 2000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma was then aspirated using sterile pastettes and 100 ml aliquoted into 10 × 1.5 ml cryovial tubes. Subsequently, all samples were snap frozen on dry ice prior to storage within labelled cryostorage boxes in a monitored −80°C freezer.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Serum siltuximab concentrations were determined using an electrochemiluminescent-based immunoassay (MesoScale Discovery - MSD®) method with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 0.045 μg/mL at a required dilution of 1:4. Validated assays were used to determine the concentration of siltuximab in the serum obtained prior to and 1 hr after each of the initial three infusions from all 18 evaluable patients.

Electrochemiluminescence cytokine detection

Cytokine concentrations were estimated using MSD® assays according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and CCL2, after defrosting at 4°C, samples were centrifuged briefly at 2000x g for 1-2 min at 4°C. These markers were pre-specified in the trial protocol as there was prior evidence that they were co-regulated with IL-6 (7). The calibrator standards, patient and normal healthy control were incubated on the MSD® microplates. Plates were washed and read using SECTOR Imager 2400 software (MSD®). For plasma VEGF uncoated single-spot microplates were developed according to manufacturer’s instructions with calibrator standards, capture and detection antibodies obtained from alternate sources (human VEGF DuoSet; DY293B). For human CXCL12 in plasma, a Quantikine® ELISA kit (R&D Systems, DSA00) was used. Absorbance at 450nm was measured and corrected at 570 nm in an Opsys MR plate reader (Dynex Technologies).

Apoptosis Marker

M30 Apoptosense® ELISA assays (PEVIVA AB, Bromma, Sweden) were performed as previously described (29). The ELISA detects a neo-epitope mapped to positions 387 to 396 of a 21-kDa fragment of cytokeratin 18 that is only revealed after caspase cleavage of the protein and is postulated as a selective biomarker of apoptotic epithelial cell death (30). The assay has been subject to extensive validation (31).

Gene Set Enrichment (GSEA) using Metacore pathway and process gene set

The microarray datasets GSE6008, GSE3149 and GSE9899 were downloaded from the GEO website [http:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo]. Data were analyzed using Bioconductor 1.9 (http://bioconductor.org) running on R 2.6.0 (32). Datasets GSE6008 and GSE3149 were merged to form one dataset. Probeset expression measures were calculated using the Affymetrix package’s Robust Multichip Average (RMA) default method (33). The function GeneSetTest from the limma package (34) was used to assess whether each sample had a tendency to be associated with an up or down regulation of members of the IL-6 pathway as defined by Metacore pathway analysis tool from Genego Inc., an integrated manually-curated knowledge database. The function employs a Wilcoxon t-test to generate p-values. All samples were ranked on this enrichment, from the most significant to the least significant. The top and bottom 50 samples were extracted from the dataset and given the names ‘high-IL-6’ and ‘low-IL-6’ respectively. The same analysis was done in both datasets and then only common differential genes were used for downstream process enrichment. Differential gene expression was assessed between high IL-6 and low IL-6 pathway groups, using an empirical Bayes’ t-test (limma package); p values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (35). Any probe sets that exhibited an adjusted p value of 0.05 were called differentially expressed. The same analysis was done in both datasets and then only common differential genes were used for downstream process enrichment. Probes were divided into positive and negative fold change lists and used to determine enrichment using GeneGo pathways and processes within the Metacore pathway tool. The analysis employs a hypergeometric distribution to determine the most enriched gene set. Heatmaps were drawn using expression data showing the probes that mapped to the biological processes of angiogenesis, apoptosis, cell cycle/proliferation and immune response/inflammation.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was evaluated using the Mann Whitney U test, unpaired t test and log-rank tests (GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software). Spearman’s Rho correlation was used to estimate the relationship between IL-6, gp80 and gp130 expression in the TMA (SPSS version 15.0 SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and all p values reported are two-sided.

The clinical trial aimed to recruit 20 patients on the assumption that 16 would be evaluable for response. This sample size was determined on the assumption that a response rate of less than 10% would be of no further interest, whereas a clinical benefit rate of 20% or more would demonstrate evidence of activity meriting further study. The observation of one response in the first 16 patients limits to 5% the probability of failing to observe a true response rate of 10%.

Results

High IL-6 expression by malignant ovarian cells is an indicator of poor prognosis

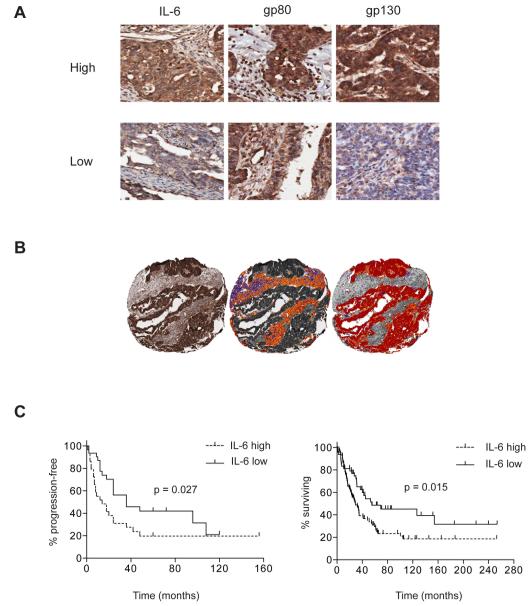

Previous results suggest that high plasma IL-6 levels are associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer (16, 17) but there is no published information as to the source of this IL-6 in tumor biopsies from patients with ovarian cancer. We therefore stained for IL-6 and its transmembrane receptors in ovarian cancer biopsies in a seventy-six patient TMA (36) and also looked for any correlations with progression-free survival. IL-6 and gp80, gp130 receptors were all found on malignant and stromal cells (Figure 1A). Automated algorithms were used to assess both malignant cell (tumor) and stromal compartments (Figure 1B), and expression levels were quantified using an autoscore that combined both the intensity and density of positive pixels. IL-6 staining was seen in the malignant cells as well as infiltrating leukocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts of the stromal areas. IL-6 staining was significantly higher in the malignant cell areas than the stromal areas (p<0.001). In addition, high (defined as greater than median) IL-6 expression by malignant cells was significantly associated with shorter progression-free survival in the whole cohort (p=0.027; Figure 1C), which was maintained when patients with serous carcinoma were analyzed separately (p=0.020; Supplementary Figure 1A). See Figure 1A for an example of high and low levels of staining for IL-6 and its receptors in the biopsies. These data were confirmed in a separate TMA of 154 ovarian cancer patients (24). Although disease-free survival data were not available for the second cohort, high (again defined as greater than median) IL-6 expression positively associated with shorter overall survival (p = 0.015; Figure 1D). However, neither IL-6 receptor expression nor stromal IL-6 associated with survival in these two cohorts (data not shown).

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical analysis of IL-6 and IL-6 receptor expression in ovarian cancer biopsies.

1A. Immunohistochemical analysis of IL-6, gp80 and gp130 expression in ovarian cancer specimens demonstrating expression in both tumor and stromal compartments. Examples are shown of high and low staining for the cytokine and its receptors.

1B. Immunohistochemical analysis of IL-6 in a TMA core (left) with example of automated analysis of staining intensity in stromal (middle) and tumor (right) cells.

1C. Progression-free survival in cohort of 76 patients with ovarian cancer according to tumor IL-6 expression (left hand graph). Overall survival in a separate cohort of 154 patients with ovarian cancer, according to tumor IL-6 expression (right hand graph).

Effects of siltuximab on human ovarian cancer cells in vitro

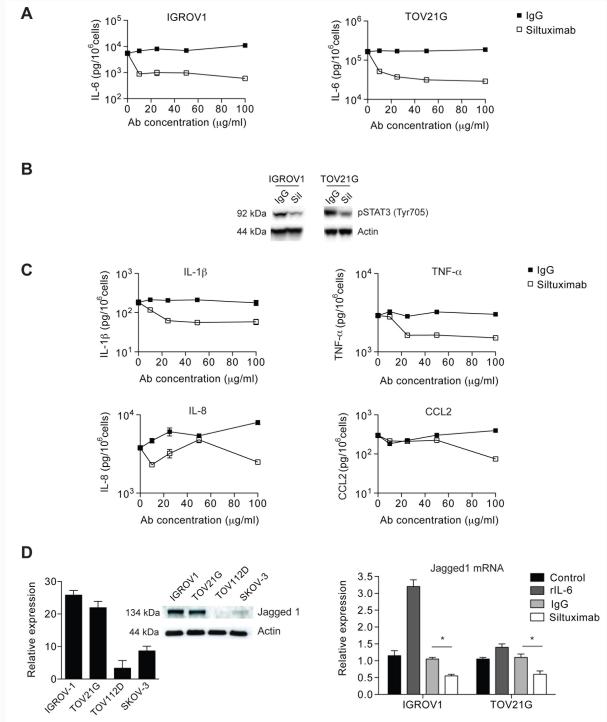

As malignant cell IL-6 had a negative influence on ovarian cancer prognosis, and malignant cells showed the highest IL-6 protein staining in the biopsies, we assessed the activity of the monoclonal anti human IL-6 antibody siltuximab on two ovarian cancer cell lines that constitutively produced IL-6 (IGROV-1 and TOV21G) and two that did not (TOV112D and SKOV-3; Supplementary Figure 1B). IL-6 production by TOV21G cells was greater than IGROV-1 cells (6824 pg/106 cells/72h and 42 pg/106 cells/72h respectively). Analysis of cell surface expression of IL-6 receptors gp80 and gp130 showed that three of the four cell lines (TOV21G, IGROV-1, SKOV-3) could potentially respond to exogenous IL-6 either bound to the cell surface or to soluble sgp80. (Supplementary Figure 1C). In vitro exposure of these ovarian cancer cells to siltuximab for 11 days had no effect on malignant cell growth even under serum-free conditions (data not shown). However, siltuximab inhibited constitutive release of IL-6 (Figure 2A), as well as IL-6 signalling as measured by a reduction in phosphorylation of the IL-6 regulated transcription factor STAT3 (Figure 2B). This suggests that there is autocrine stimulation of IL-6 production in these ovarian cancer cells that also express IL-6 receptors.

Figure 2. In vitro effects of siltuximab on ovarian cancer cells.

2A. In vitro inhibition of IL-6 release in IGROV-1 and TOV21G ovarian cancer cells by siltuximab (10 - 100μg/ml) for three days

2B. Protein was extracted from IGROV1 and TOV21G cells treated with siltuximab (Sil) or IgG control and blotted for expression of Tyr705 phospho-STAT3.

2C. In vitro inhibition of IL-6 release in both IGROV-1 and TOV21G cell lines also led to reduced release of other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Typical results of two experiments performed in IGROV1 cells are presented.

2D. Expression of Jagged-1 in unstimulated ovarian cancer cells was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot (left). Following stimulation with either 20 ng/ml IL-6, IgG control or siltuximab for 48 hours, Jagged-1 expression was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (right). Data are representative of three independent experiments performed. *p<0.05

We also found inhibition of constitutive release of other cytokines that are part of an autocrine cytokine network in ovarian cancer cells (7), IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8 and CCL2 (Figure 2C), in the IL-6 secreting IGROV-1 and TOV21G cells, but there was no effect on IL-6 negative lines (data not shown). Recently, we found that constitutive production of the angiogenic factor Jagged1 in ovarian cancer cells was also associated with this autocrine cytokine network (Kulbe et al submitted for publication). Baseline Jagged1 expression was higher in the IL-6 secreting cell lines, and was stimulated by IL-6 and inhibited by siltuximab (Figure 2D). This shows that an antibody that prevents the binding of constitutively-produced IL-6 to IL-6 receptors that are also present on the ovarian cancer cells will inhibit the production of IL-6 and other cytokines and chemokines that are part of an autocrine cytokine network in the malignant cells. Although IL-6 inhibition impacts on constitutive production of other inflammatory and angiogenic mediators by ovarian cancer cells, it does not alter malignant cell growth or survival at least in tissue culture where there were no stromal influences.

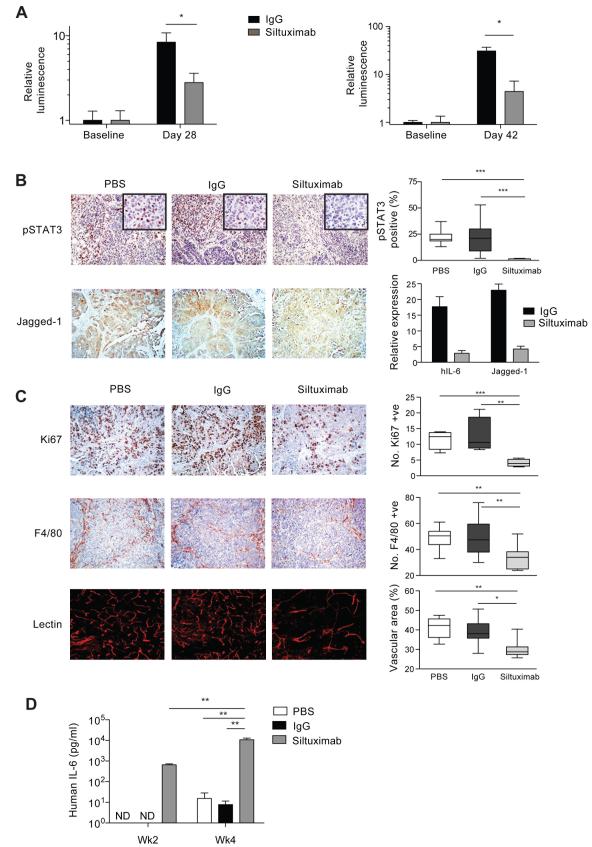

Actions of siltuximab on human ovarian cancer xenografts

To investigate the influence of the microenvironment, we grew the ovarian cancer cells as intraperitoneal xenografts in nude mice and treated with siltuximab (20mg/kg given twice-weekly intraperitoneally). Four weeks of twice-weekly siltuximab injections significantly reduced growth (p<0.05) of IGROV-1 tumors whether treatment started one (Figure 3A left) or fourteen days (Figure 3A right) after tumor initiation, but had no impact on tumor growth in IL-6-negative TOV112D or SKOV-3 xenografts (data not shown). In the experiment where treatment was started one day after tumor cell injection, there was a 66% reduction in relative luminescence after four weeks treatment with siltuximab compared to a control IgG. In the experiment where treatment started 14 days after tumor cell injection, the siltuximab group had an 84% reduction in relative luminescence compared to control IgG. Siltuximab treatment of tumors from TOV21G cells, which produce higher concentrations of IL-6 in vitro than IGROV-1, produced consistent inhibition of tumor growth in two experiments, although this did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Figure 2A).

Figure 3. Actions of siltuximab on intraperitoneal tumors formed from IGROV-1 cells.

3A. Luciferase bioluminescence imaging was used to measure intraperitoneal tumor burden. Siltuximab (20mg/kg twice weekly) treatment for four weeks started 1 day (left) or 14 days (right) after tumor cell injection, and significantly reduced tumor burden compared to IgG control (* p < 0.05). All mice were killed after four weeks of treatment.

3B. Effects of siltuximab on IL-6, phospho-STAT3 and Jagged1 expression in the IGROV-1 xenograft model following 4 weeks of siltuximab. The number of tumor cell nuclei showing positive staining for pSTAT3 were counted in 3 randomly selected areas per tumor section (n=3) using a x40 objective with approximately 500 nuclei counted per tumor (***; p < 0.0001). After 4 weeks of siltuximab treatment, there were also marked decreases in both human IL-6 and Jagged1 mRNA expression. RNA from 3 tumor samples in each group was used for this analysis. In addition, there was a reduction in Jagged-1 expression as detected by immunohistochemistry. Main photomicrographs taken with x10 magnification lens, inset x40.

3C. Ki67, F4/80 and tumor vasculature staining and quantification in IGROV-1 xenograft. Siltuximab significantly reduced cell proliferation compared to IgG control in IGROV-1 xenografts (***; p < 0.001). The proliferative index was calculated by estimating the percentage of tumor cells in 10 randomly selected areas per tissue section (n = 3) showing positive staining. Significant decreases in macrophage influx were seen with siltuximab compared to IgG control in the IGROV-1 xenograft (**; p < 0.01). The quantification was calculated by counting the number of F4/80+ cells from 10 randomly selected areas per tumor section (n = 3). Siltuximab also had a significant effect on tumor vasculature (*; p = 0.0263). The mean vascular area in each group was quantified by selecting 10 random areas per tumor section (n=3). All data are representative of two independent experiments.

3D. Human IL-6 was measured in serum of mice bearing IGROV-1 xenografts. After 4 weeks, hIL-6 significantly increased with siltuximab treatment (**; p = 0.01). ND = Not Detected

Siltuximab significantly reduced nuclear phospho-STAT3 expression in IGROV1 tumors compared to PBS or IgG, induced a significant reduction in human IL-6 (hIL-6) gene transcription after four weeks of treatment and had a strong inhibitory effect on Jagged1 protein and mRNA expression in IGROV1 tumors (Figure 3B). Siltuximab also had significant inhibitory effects on tumor cell proliferation, F4/80+ macrophage infiltration and angiogenesis in both IGROV-1 and TOV21G tumors (Figure 3C, Supplementary Figure 2B), although differences were more pronounced in IGROV-1.

Human IL-6 was detected in serum of control mice four weeks after IGROV-1 tumors were established (Figure 3D). In TOV21G-bearing mice, hIL-6 was detected earlier and at higher levels than in IGROV-1-bearing mice (Supplementary Figure 2C). However, hIL-6 was detected in the serum of all siltuximab-treated mice after two weeks and levels increased one log further after four weeks (Figure 3D). As hIL-6 mRNA was strongly decreased in tumors, this indicates that human IL-6 is sequestered by circulating antibody without a compensatory increase in tumor IL-6 production.

These results show that anti-IL-6 antibodies have greater activity when ovarian cancer cells are growing in a peritoneal environment.

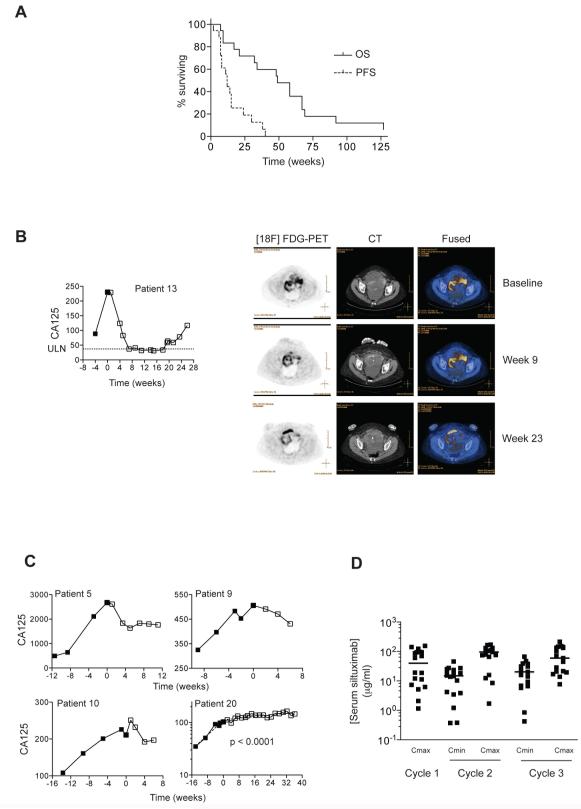

A phase II clinical trial of siltuximab in women with advanced platinum-resistant ovarian cancer

In view of the data described above and previously published literature on IL-6 and ovarian cancer, we undertook a single arm, phase II clinical trial in patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer. Intravenous siltuximab (5.4 mg/kg ideal body weight) was administered every two weeks until disease progression and was well tolerated. Details of adverse events are in Supplementary Table 3. Nineteen patients had high-grade serous ovarian cancer and one patient had clear cell ovarian cancer.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 12 weeks and median overall survival (OS) was 49 weeks (Figure 4A). Of the eighteen evaluable patients, sixteen have died, one patient is alive 127 weeks after trial entry, and one was lost to follow-up. By RECIST alone, there were no complete or partial responses. In eight patients, however, stable disease (SD) was achieved, lasting 6 months or more in four patients. Disease progressed in ten patients (PD). One patient had a partial response (PR) by combined RECIST/CA125 criteria (37), which was accompanied by a reduction in [18F] FDG uptake as detected by PET/CT imaging (Mean SUVMax baseline = 6.0; week 23 = 4.1; Figure 4B). Rising CA125 values declined in three other patients (Figure 4C), whilst in patient 20, there was a significant change in CA125 doubling time (38) after commencing treatment. CA125 continued to rise in all patients who progressed by RECIST on treatment (data not shown). Pharmacokinetic analysis (Figure 4D) indicated that the serum concentrations of siltuximab were at levels that had inhibited constitutive cytokine release by malignant cells in vitro (see Figure 2A and C); the median Cmax in cycle 3 was 59.1 μg/ml (95% CI 45.0 – 110.6 μg/ml).

Figure 4. Phase II trial of the anti-IL-6 antibody siltuximab – survival, clinical responses and pharmacokinetics.

4A. 18 women with recurrent, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer received bi-weekly infusions of siltuximab. Patients were re-staged after 3 (12 patients) or 5 (6 patients) doses and every 12 weeks thereafter. Those achieving Stable Disease (SD) after 3 – 5 doses continued treatment for up to 17 infusions. The median progression-free and overall survival, PFS and OS respectively, of the patients who received at least one infusion of siltuximab was 12 and 49 weeks respectively.

4B. CA125 was measured at enrolment and prior to each infusion of siltuximab. Patient 13 had a CA125 response by GCIG criteria. PET/CT images at baseline, Week 9 (5 cycles), Week 23 (12 cycles) indicated reduction in [18F]-FDG uptake in pelvic tumors. The region of high [18F]-FDG uptake anteriorly on the week 23 scan represents the bladder. ULN: Upper Limit of Normal

4C. CA125 values prior to and during siltuximab treatment. Patients 5, 9 and 10 had reductions in CA125 lasting up to 12 weeks. In patient 20, there was a highly significant change in CA125 doubling time slope after commencing treatment.

4D. Siltuximab pharmacokinetics. Serum siltuximab levels were measured immediately prior to (Cmin) and one hour after (Cmax) the first three doses of siltuximab.

Plasma biomarkers in response to siltuximab treatment

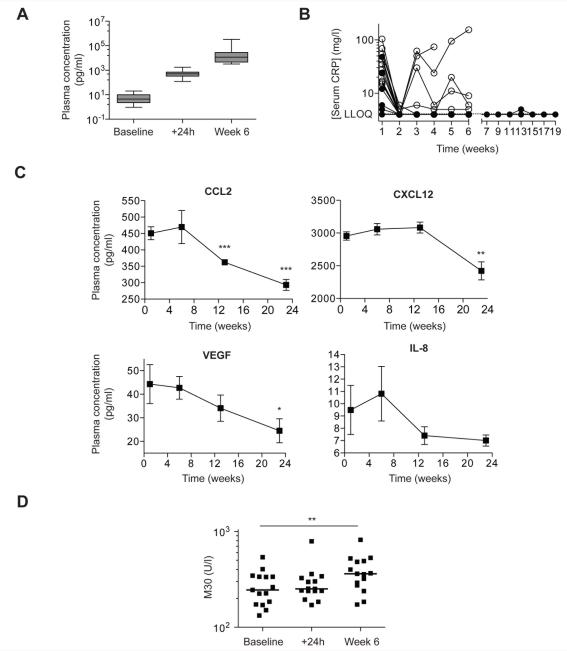

We measured IL-6 and IL-6-regulated cytokines in patient plasma in an attempt to understand mechanisms of action of the anti-IL-6 antibody and identify potential biomarkers of response. Twenty-four hours after the first antibody infusion, there was a highly significant rise in measurable plasma IL-6, which continued after six weeks (Figure 5A). Free IL-6 could not be detected, suggesting that the assay was detecting siltuximab-bound IL-6, in line with the xenograft data (See Figure 3D) as well as observations in other clinical trials of siltuximab (39), antibodies to the IL-6 receptor or to TNF-α (40, 41).

Figure 5. Pharmacodynamic analysis of the phase II trial of anti-IL-6 antibody siltuximab.

5A. Plasma levels of IL-6 were measured by electrochemiluminesence assay at baseline, 24 hours after first infusion and at week 6.

5B. CRP was measured weekly for the first 6 weeks and every two weeks thereafter. CRP fell in all patients after one dose of siltuximab. In the 8 patients who achieved SD (closed circles) after 3 – 5 doses of siltuximab, CRP remained suppressed for up to 19 weeks, whilst suppression was not maintained in 4 of 10 patients who disease progressed at first re-staging (open circles). LLOQ: Lower Limit of Quantification.

5C. Plasma levels of CCL2, CXCL12, VEGF and IL-8 were measured in the four patients (12, 13, 16, 20) who received infusions of siltuximab for at least 6 months. Points represent mean ± sem. *; p < 0.05, **; p < 0.01, ***; p < 0.001 compared to week 1.

5D. Apoptosis marker M30 plasma levels baseline, 24 hours and 6 weeks post infusion. There was a significant rise between baseline and week 6 (**; p < 0.01).

There was a close correlation between baseline plasma IL-6 levels and serum levels of the inflammatory marker CRP (r2 = 0.74, Spearman Rho = 0.87; Supplementary Figure 3A). CRP levels declined in all patients after one dose of siltuximab (Figure 5B) and fell below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) in 16 of the 18 evaluable patients. CRP remained suppressed for up to 19 weeks in patients who achieved SD, but was not maintained in four of the ten patients progressed during the first 3 – 5 treatments with siltuximab. There were no episodes of thrombocytopenia greater than grade 1 (platelet count 75-100 × 109/l), but two patients experienced one episode each of grade 3 neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count 0.5-1.0 × 109/l): each lasted less than one week and recovered spontaneously without growth factor support (Supplementary table 3). There was a significant increase in Hb levels in the fourteen patients who did not receive blood transfusions during the trial (Supplementary Figure 3B). Plasma cytokine/chemokine levels were largely unchanged after three doses of siltuximab (Supplementary Figure 3C). However, there was evidence that longer IL-6 blockade reduced plasma cytokine and chemokine levels. In the four patients who received at least six months treatment, there were significant declines in the IL-6 regulated chemokines CCL2, CXCL12 as well as the angiogenic factor VEGF. There was also a trend towards reduced IL-8 levels (Figure 5C).

Although we could find no direct effects of siltuximab on ovarian cancer cells in vitro, potential effects on angiogenesis and macrophage infiltrate could have induced cell death in the tumor microenvironment. We therefore looked for evidence of apoptosis in patient plasma, measuring the cytokeratin 18 neo-epitope M30, a marker of executioner caspase activation in epithelial cells (42). Median M30 levels increased significantly between baseline and 6 weeks (Figure 5D).

IL-6/IL-6 receptor expression in diagnostic biopsies from trial patients and an independent cohort

Diagnostic tumor biopsies were available from fourteen of the trial patients. Median tumor-specific IL-6 and gp130 expression was higher in SD/PR patients compared to PD patients (Supplementary Figure 3D and E), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.103 for IL-6). There were no differences in tumor-specific gp80 expression or stromal IL-6, gp80 or gp130 between the groups (data not shown).

Bioinformatics analysis of IL-6-linked pathways and processes in ovarian cancer biopsies

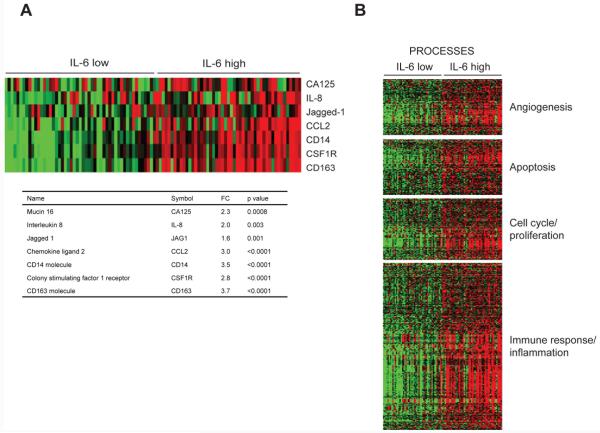

From the tissue culture, xenograft and clinical trial data, we predicted that IL-6 is involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines, angiogenesis and the infiltration of macrophages into the tumor microenvironment in ovarian cancers in which the malignant cells produce IL-6. To seek further confirmation of our findings, we studied human ovarian cancer biopsies for correlations between gene expression levels in the IL-6 pathway and expression of mediators that were down-regulated by siltuximab in the clinical and pre-clinical experiments described above. We used gene expression data from 285 ovarian cancer biopsies from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study (AOCS) (GSE9899) (43) and ranked all samples for expression of IL-6 pathway genes (defined by the Metacore pathway tool). We then selected the 50 samples with the highest (‘high IL-6’) and 50 with the lowest (‘low IL-6’) levels of expression of genes in this pathway. Next, we generated a list of genes that were differentially expressed between the high IL-6 and low IL-6 samples (fdr <0.05). A similar process was performed on a further 245 samples obtained by merging two other publicly available datasets (GSE6008 and GSE3149). All samples were used in each of the datasets for these analyses. We took forward genes that were differentially expressed in both analyses and found that high IL-6 pathway expression correlated positively with four of the genes whose levels were reduced by siltuximab treatment, namely CA125, IL-8, Jagged1 and CCL2 (all p<0.003). There was also positive correlation with the macrophage cell surface markers CD14, CSF1R, CD163 (Figure 6A) (all p<0.0001). Using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and Metacore, we found significant associations between high IL-6 pathway gene expression and the following pathways/processes: development blood vessel morphogenesis; regulation of angiogenesis; development-role of IL-8 in angiogenesis; developmental VEGF signalling and activation; apoptosis/anti-apoptosis, cell cycle/proliferation and immune response/inflammation (all p<0.001) (Figure 6B). A full list of genes associated with high levels of IL-6 signalling pathway combining all information from the three datasets can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 6. Bioinformatic analysis of IL-6 pathway gene expression in ovarian cancer biopsies.

6A. Expression profile across the 50 highest and lowest ranked IL-6 pathway samples. RMA normalised expression values for the seven genes were used to generate a heatmap. The colours indicate the expression value relative to the median expression value per gene in the dataset. Red indicates upregulation relative to median value and green indicates downregulation relative to the median value. The table shows the fold change and associated adjusted p value showing the difference between the top and bottom 50 IL-6 pathway ranked samples.

6B. Process enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. Differentially expressed probes between the 50 top and bottom ranked IL-6 samples were selected based on meeting the criteria of false discovery rate, FDR<0.05. Probes were divided into positive and negative fold changes lists and used to determine enrichment using Genego processes within Metacore pathway. Processes were grouped based on annotated biological groups of Angiogenesis, Apoptosis, Cell cycle / proliferation and Immune response / inflammation. Heat maps were drawn for each biological process using the Cluster package using average linkage hierarchical algorithm to cluster the probes.

Discussion

In this paper, we have shown how IL-6 production by malignant ovarian cancer cells stimulates inflammatory cytokine production, tumor angiogenesis, the tumor macrophage infiltrate and is associated with a poor prognosis. We also show that the anti-human IL-6 monoclonal antibody siltuximab, when given as a single agent, has some clinical activity recurrent, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. A total of eight patients achieved radiological disease stabilisation, which lasted six months or more in four cases. One of these eight also had normalisation of CA125 that lasted for 12 weeks, giving an overall partial response by combined RECIST/CA125 criteria. Combining results from clinical, pre-clinical and in silico analysis, we conclude that the mechanisms of action of anti-IL-6 in ovarian cancer are inhibition of an autocrine cytokine and chemokine network in the malignant cells that has paracrine actions on angiogenesis via inhibition of VEGF, Jagged1 and IL-8, and on the macrophage infiltrate via inhibition of the chemoattractant CCL2. These conclusions were supported by gene expression analyses, in which IL-8, CCL2 and macrophage and angiogenesis markers all correlated significantly with highest levels of gene expression in the IL-6 pathway. There was no evidence of a direct growth inhibitory action of the anti-IL-6 antibody on ovarian cancer cells, effects on their survival were only evident in the presence of a tumor stroma suggesting that this was an indirect effect.

This is the first clinical study of anti-IL-6 therapy in ovarian cancer. Siltuximab has been evaluated recently in phase II trials in Castleman’s disease (26) and castration-resistant prostate cancer (39). In Castleman’s Disease, in which IL-6 is a key pathogenic driver, the objective response rate was 52%: by contrast, in prostate cancer, the response rate was 3.2%. Although the response rate here (5.6% by combined CA125/RECIST criteria) is modest, prolonged periods of disease stabilisation were seen in women with recurrent, drug-resistant disease, as well as some evidence of activity on [18F]-FDG PET imaging. The median overall survival in this trial was similar to that seen in large randomised phase III trials of conventional chemotherapy, such as topotecan, liposomal doxorubicin and gemcitabine, in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (44, 45). However, larger randomised studies will be required to allow robust statistical conclusions to be drawn about the role of IL-6 inhibition in ovarian cancer treatment and to validate the biomarkers identified in our study.

At trial entry, there were no differences in clinical parameters between the patients who had stable disease and those who progressed through siltuximab treatment; all had platinum-resistant disease and the diagnostic biopsies from the stable disease patients tended to show higher expression of malignant cell IL-6, a feature that was associated with a shorter survival in the TMA cohorts. Nonetheless, it will be important in any future clinical trial to obtain new biopsies at time of trial enrolment to measure IL-6 activity by IHC and gene expression array and relate this to pre-treatment plasma levels, especially as recent results suggest that tumor IL-6 expression is greater in recurrent ovarian cancer compared to matched primary disease (46).

Pharmacodynamic data from a phase I trial of siltuximab in metastatic renal cell cancer, as well as modelling data, suggest that the dose regime used in this trial (6mg/kg every 2 weeks) should be sufficient to suppress CRP to below 5 mg/l in all patients with a baseline value >10 mg/l (27). Our results show that such suppression can be achieved by day 8 in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients. However, in four patients, whose mean baseline CRP was 50 mg/l, CRP suppression was transient and all four had progressive disease at first evaluation. Thus, it is possible that ovarian cancer patients with high baselines CRP values may require greater doses of anti-IL-6 antibodies for maximum pathway suppression.

In vitro, exposure of ovarian cancer cells that expressed IL-6 and its cell surface receptors to siltuximab inhibited constitutive release of IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines. In xenograft experiments, siltuximab only inhibited growth of tumors that produced IL-6, and its actions were associated with a strong decline in human IL-6 and Jagged1 mRNA. As we did not have a mouse phenocopy of siltuximab and the anti-human IL-6 antibody does not neutralise murine IL-6, we could not fully recreate the effects of an anti-IL-6 antibody in a microenvironment where malignant cells and stroma are syngeneic. However, these experiments did show that plasma levels of human IL-6 in the nude mice were determined by both the inherent ability of the malignant cells to produce IL-6 and the tumor burden.

The majority of the work in this paper relates to high-grade serous ovarian cancer. However, more recently, we have found that clear cell ovarian cancer is characterised by specific overexpression of an IL-6-STAT3-HIF pathway (8). Treatment of two patients with the multireceptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib induced changes in CA125 and FDG uptake that were maintained for 20 months in one of the two patients. The TOV21G cell line used in our study comes from a clear cell carcinoma (25) and one of the patients in the trial was also diagnosed as clear cell carcinoma. This patient also had the highest pre-treatment levels of both IL-6 (20.1 pg/ml) and CRP (69 mg/l). Further studies in clear cell carcinoma specifically are required to investigate the role of IL-6 in this ovarian cancer subtype.

Our results show that IL-6 stimulates inflammatory cytokine production, tumor angiogenesis and the tumor macrophage infiltrate in ovarian cancer and these actions can be inhibited by a neutralising anti-IL-6 antibody in pre-clinical and clinical studies. Further clinical studies of IL-6 antagonists alone or in combination with other therapies are warranted. In view of the anti-angiogenic effects reported in this paper and the encouraging results seen with recent GOG218 and ICON-7 studies of bevacizumab, we believe that a randomised trial of silituximab may be warranted in the maintenance setting.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Tables 1-3

Supplementary Table 4

Translational relevance.

As interleukin 6 (IL-6) is a major mediator of cancer-related inflammation, we investigated the therapeutic potential of IL-6 inhibition in ovarian cancer. The anti-IL-6 antibody siltuximab inhibited IL-6 signalling in ovarian cancer cells, with therapeutic effects in xenograft models, accompanied by reductions in angiogenesis and macrophage infiltration. In a phase II clinical trial in 18 women with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, single agent siltuximab was well-tolerated and had some therapeutic activity. Four patients had stable disease for 6 months or more, with reductions in plasma in the macrophage chemokines CCL2, CXCL12 and the angiogenic factor VEGF. Further clinical trials of siltuximab in ovarian cancer are indicated, with an emphasis on identifying subgroups of patients most likely to respond, especially as we found that some biopsies had high levels of IL-6 protein in the malignant cells and this was a poor prognostic sign.

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This study was funded by the Medical Research Council and siltuximab was provided free by OrthoBio R&D Oncology, Division of Centocor BV, The Netherlands. JN and JV are employees of OrthoBio R&D Oncology.

References

- 1.Naugler WE, Karin M. The wolf in sheep’s clothing: the role of interleukin-6 in immunity, inflammation and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grivennikov S, Karin M. Autocrine IL-6 signaling: a key event in tumorigenesis? Cancer Cell. 2008;13:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 Are Required for Survival of Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Development of Colitis-Associated Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollrath J, Phesse TJ, von Burstin VA, et al. gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromberg J, Wang TC. Inflammation and Cancer: IL-6 and STAT3 Complete the Link. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ancrile B, Lim K-H, Counter CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL-6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes and Development. 2007;21:1714–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulbe H, Thompson RT, Wilson J, et al. The inflammatory cytokine TNF-a generates an autocrine tumour-promoting network in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:585–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anglesio MS, George J, Kulbe H, et al. Il6-Stat3-Hif Signalling and Therapeutic Response to the Angiogenesis Inhibitor, Sunitinib, in Ovarian Clear Cell Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shain KH, Yarde DN, Meads MB, et al. β1 Integrin Adhesion Enhances IL-6-Mediated STAT3 Signaling in Myeloma Cells: Implications for Microenvironment Influence on Tumor Survival and Proliferation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1009–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimoto N, Kanakura Y, Aozasa K, et al. Humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment of multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2005;106:2627–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007 doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan Z, Foster R, Bell DA, et al. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 pathway activation in drug-resistant ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5055–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo CW, Chen MW, Hsiao M, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling in formation and progression of malignant ascites in ovarian cancer. Cancer research. 2011;71:424–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson MB, Langley RR, Fidler IJ. Interleukin-6, secreted by human ovarian carcinoma cells, is a potent proangiogenic cytokine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10794–800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyahara Y, Odunsi K, Chen W, Peng G, Matsuzaki J, Wang R-F. Generation and regulation of human CD4+ IL--17-producing T cells in ovarian cancer. PNAS. 2008;105:15505–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710686105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutgendorf SK, Weinrib AZ, Penedo F, et al. Interleukin-6, cortisol, and depressive symptoms in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4820–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scambia G, Testa U, Panici PB, et al. Prognostic significance of interleukin 6 serum levels in patients with ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:354–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plante M, Rubin SC, Wong GY, Federici MG, Finstad CL, Gastl GA. Interleukin-6 level in serum and ascites as a prognostic factor in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:1882–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940401)73:7<1882::aid-cncr2820730718>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saccani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, et al. p50 nuclear factor-kappaB overexpression in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits M1 inflammatory responses and antitumor resistance. Cancer research. 2006;66:11432–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffelt SB, Marini FC, Watson K, et al. The pro-inflammatory peptide LL-37 promotes ovarian tumor progression through recruitment of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:3806–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900244106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1555–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan DJ, Ek S, Doyle E, et al. The transcription factor Sox11 is a prognostic factor for improved recurrence-free survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1510–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kononen J, Bubendorf L, Kallioniemi A, et al. Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat Med. 1998;4:844–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehlen A, Brennan DJ, Nodin B, et al. Expression of the RNA-binding protein RBM3 is associated with a favourable prognosis and cisplatin sensitivity in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Transl Med. 2010;8:78. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Provencher DM, Lounis H, Champoux L, et al. Characterization of four novel epithelial ovarian cancer cell lines. In vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2000;36:357–61. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2000)036<0357:COFNEO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rhee F, Fayad L, Voorhees P, et al. Siltuximab, a novel anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, for Castleman’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3701–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puchalski T, Prabhakar U, Jiao Q, Berns B, Davis HM. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of an anti-interleukin-6 chimeric monoclonal antibody (siltuximab) in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1652–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avril N, Sassen S, Schmalfeldt B, et al. Prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy by sequential F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummings J, Ward TH, LaCasse E, et al. Validation of pharmacodynamic assays to evaluate the clinical efficacy of an antisense compound (AEG 35156) targeted to the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein XIAP. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:532–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagg M, Biven K, Ueno T, et al. A novel high-through-put assay for screening of pro-apoptotic drugs. Invest New Drugs. 2002;20:253–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1016249728664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greystoke A, Cummings J, Ward T, et al. Optimisation of circulating biomarkers of cell death for routine clinical use. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:990–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Team RDC . R: A Language and environment for statistical computing: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. Affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–15. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. 2005:397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. JRoy Stat Soc, Ser B. 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan DJ, Brandstedt J, Rexhepaj E, et al. Tumour-specific HMG-CoAR is an independent predictor of recurrence free survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rustin GJ, Bast RC, Jr., Kelloff GJ, et al. Use of CA-125 in clinical trial evaluation of new therapeutic drugs for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3919–26. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed N, Abubaker K, Findlay J, Quinn M. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like phenotypes facilitate chemoresistance in recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:268–78. doi: 10.2174/156800910791190175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorff TB, Goldman B, Pinski JK, et al. Clinical and correlative results of SWOG S0354: a phase II trial of CNTO328 (siltuximab), a monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6, in chemotherapy-pretreated patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3028–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, Nakahara H, Takagi N, Kakehi T. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum intrleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood. 2008;112:3959–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrison ML, Obermueller E, Maisey NR, et al. Tumor necrosis factor a as a new target for renal cell carcinoma: two sequential phase II trials of infliximab at standard and high dose. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4542–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biven K, Erdal H, Hagg M, et al. A novel assay for discovery and characterization of pro-apoptotic drugs and for monitoring apoptosis in patient sera. Apoptosis. 2003;8:263–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1023672805949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tothill RW, Tinker aV, George J, et al. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometroid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5198–208. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, Parkin DE, Gore ME, Lacave AJ. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mutch DG, Orlando M, Goss T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2811–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo Y, Nemeth JA, O’Brien C, et al. Effects of Siltuximab on the IL-6 Induced Signaling Pathway in Ovarian Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5759–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Tables 1-3

Supplementary Table 4