The Atg18-Atg2 Complex Is Recruited to Autophagic Membranes via Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate and Exerts an Essential Function (original) (raw)

Abstract

Atg18 is essential for both autophagy and the regulation of vacuolar morphology. The latter process is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate binding, which is dispensable for autophagy. Atg18 also binds to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P) in vitro. Here, we investigate the relationship between PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 and autophagy. Using an Atg18 variant, Atg18(FTTG), which is unable to bind phosphoinositides, we found that PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is essential for full activity in both selective and nonselective autophagy. Atg18(FTTG) formed a complex with Atg2 in a normal manner, and Atg18-Atg2 complex formation occurred in cells in the absence of PtdIns(3)P, indicating that Atg18-Atg2 complex formation is independent of PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18. Atg18 localized to endosomes, the vacuolar membrane, and autophagic membranes, whereas Atg18(FTTG) did not localize to these structures. The localization of Atg2 to autophagic membranes was also lost in Atg18(FTTG) cells. These data indicate that PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 is involved in directing the Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes. Connection of a 2×FYVE domain, a specific PtdIns(3)P-binding domain, to the C terminus of Atg18(FTTG) restored the localization of Atg18-Atg2 to autophagic membranes and full autophagic activity, indicating that PtdIns(3)P-binding by Atg18 is dispensable for the function of the Atg18-Atg2 complex but is required for its localization. This also suggests that PtdIns(3)P does not act allosterically on Atg18. Taken together, Atg18 forms a complex with Atg2 irrespective of PtdIns(3)P binding, associates tightly to autophagic membranes by interacting with PtdIns(3)P, and plays an essential role.

Eukaryotic cells are equipped with a self-digestion system called macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy). Autophagy is primarily utilized to recycle macromolecules under starvation conditions to allow survival (1,2). In addition, recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy has a variety of other physiological functions, including clearance of aggregate-prone proteins, defense against pathogens, and antigen presentation (reviewed in Ref.2). These diverse functions are supported by common processes: sequestration of cytoplasmic components and digestion within the lytic compartment, the vacuole, or lysosome. The morphology of these processes has been studied extensively in starved yeast cells. Upon starvation, a cup-shaped membrane structure, called the isolation membrane, emerges in the cytoplasm and extends to enwrap a portion of the cytoplasm (3). The ends of the isolation membrane are sealed to generate a closed double-membrane structure, the autophagosome. The outer membrane of the autophagosome fuses with the vacuole, and the inner membrane structure, the autophagic body, is released into the lumen of the vacuole, where it is immediately degraded. Similar processes can be seen in autophagosome formation in starved mammalian cells (4). The discovery of autophagy in yeast cells and the subsequent isolation of autophagy-defective mutants have enabled the study of autophagy at the molecular level (5,6). To date, 31 ATG (autophagy-related) genes have been identified (6-8); among them, at least 18 genes are essential for normal autophagosome formation. The corresponding 18 Atg proteins are classified into five functional groups: (i) the protein kinase, Atg1, and associated proteins; (ii) the phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns)2 3-kinase complex; (iii) proteins involved in ubiquitin-like conjugation of Atg12 and Atg5; (iv) proteins involved in ubiquitin-like conjugation of Atg8 and phosphatidylethanolamine; and (v) proteins with unknown functions, including Atg2, Atg18, and Atg9. Characterization of each protein has been ongoing, and investigations into the interrelationships among these functional groups have also begun (1,9). However, in contrast to the detailed morphological descriptions, insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying autophagosome formation has been slow in coming.

The PtdIns 3-kinase complex plays an essential role during autophagy both in yeast and animal cells (10,11). In yeast, Vps34, the sole PtdIns 3-kinase, forms two distinct protein complexes (complexes I and II) that function in different cellular processes: complex I is essential for autophagy, whereas complex II functions in vacuolar protein sorting via the endosome (11). The function of complex I in autophagy is specified by localization to the preautophagosomal structure (PAS), a perivacuolar structure where Atg proteins are localized (12), by a specific subunit, Atg14 (13). Although Atg14 homologues have not been reported in animal cells, a similar mechanism is assumed to exist, since the mammalian homologue of Vps34 is also required both for autophagy and the sorting of lysosomal proteins (10,14,15). PtdIns 3-kinase activity of Vps34 is essential for autophagy (16), and its product, PtdIns 3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P), is highly enriched on isolation membranes, autophagosomes, and ambiguous structures near the elongating tips of isolation membranes, implying the direct involvement of this phosphoinositide in autophagosome formation (16). Missing from the current model is the function of PtdIns(3)P in autophagosome formation.

Atg18 is proposed to function downstream of PtdIns(3)P because it is able to bind phosphoinositides, including PtdIns(3)P, in vitro. Atg18 has a putative phosphoinositide-binding motif, FRRG, within a predicted seven-bladed β-propeller structure (17). Substitution of the FRRG motif to FTTG causes loss of in vitro phosphoinositide binding (17,18). Interestingly, it was reported that this variant retains bulk autophagic activity, whereas the Cvt (cytoplasm to vacuole targeting) pathway, a type of selective autophagy, is completely blocked (18). From these results, it was concluded that phosphoinositide-binding by Atg18 is required for the Cvt pathway but not for autophagy.

How PtdIns(3)P binding by Atg18 is involved in autophagy remains unclear. Here, we determine Atg18-related steps that require or do not require Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding during autophagy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

_Yeast Strains and Media_—The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study were derived from SEY6210 (19) or BJ2168 (Yeast Genetic Stock Center, Berkley, CA), as specified inTable 1. We used standard methods and media for yeast manipulation (20). Autophagy was induced by transferring the cells into nitrogen-depleted medium SD (-N) (0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate and 2% dextrose) or nitrogen- and carbon-depleted medium S (-NC) (0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate). Rapamycin was directly added to the medium at a final concentration of 0.2 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | _MAT_α leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3_Δ_200 trp1_Δ_901 lys2-801 suc2_-Δ_9 | Robinson et al. (19) |

| STY679 | SEY6210 _atg18_Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| STY757 | SEY6210 _atg2_Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| YOK161 | SEY6210 _vps34_Δ::TRP1 | Obara et al. (16) |

| YOK856 | SEY6210 SNF7::SNF7-mRFP-natNT2 ATG18::ATG18-GFP-kanMX | This study |

| YOK815 | SEY6210 SNF7::_SNF7-mRFP-kanMX atg18_Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| YOK1246 | SEY6210 SNF7::SNF7-mRFP-natNT2 ATG18::_ATG18-GFP-kanMX atg2_Δ::spHIS5 | This study |

| YOK1269 | SEY6210 SNF7::SNF7-mRFP-natNT2 ATG2::_ATG2-GFP-kanMX atg18_Δ::spHIS5 | This study |

| YOK1245 | SEY6210 leu2::mRFP-Apel-LEU2 ATG18::_ATG18-GFP-kanMX atg2_Δ::spHIS5 | This study |

| YOK1270 | SEY6210 leu2::_mRFP-Apel-LEU2 atg18_Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| YOK1268 | SEY6210 leu2::mRFP-Apel-LEU2 ATG2::_ATG2-GFP-kanMX atg18_Δ::spHIS5 | This study |

| KVY55 | SEY6210 _pho8_Δ::PHO8_Δ_60 | Kirisako et al. (33) |

| STY442 | SEY6210 _pho8_Δ::_PHO8_Δ_60 atg18_Δ::kanMX | This study |

| ORY1800 | SEY6210 ATG18::ATG18-GFP-kanMX | Suzuki et al. (9) |

| ORY1802 | SEY6210 ATG18::_ATG18-GFP-kanMX atg2_Δ::spHIS5 | Suzuki et al. (9) |

| ORY0200 | SEY6210 ATG2::ATG2-GFP-kanMX | Suzuki et al. (9) |

| ORY0218 | SEY6210 ATG2::_ATG2-GFP-kanMX atg18_Δ::spHIS5 | Suzuki et al. (9) |

| BJ2168 | MATa leu2 trp1 ura3-52 pep4-3 prb1-1122 prc1-407 | Yeast Genetic Stock Center |

| STY1228 | BJ2168 _atg18_Δ::kanMX | This study |

| STY477 | BJ2168 _atg2_Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| YOK1250 | BJ2168 _atg18_Δ::_kanMX atg2_Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| YOK942 | BJ2168 _vps34_Δ::LEU2 | This study |

Genetic and DNA Manipulations_—Gene disruption was performed by replacing the entire coding region or part of it with a marker gene. Successful gene disruption was verified by PCR and immunoblot analysis. The_SNF7-mRFP strain was generated as follows. The sequence encoding monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) (21) was amplified by PCR from the mRFP sequence on the pRSETB vector obtained from the Carlsberg Research Center, such that PacI and AscI sites were generated at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The amplified fragment was ligated into PacI/AscI-digested pFA6a-GFP (S65T)-kanMX6 to replace the GFP sequence. The region containing mRFP, the ADH1 termination sequence, and the kanMX6 marker was amplified by PCR with a primer set containing the homologous region of the target gene. Amplified cassettes were inserted directly into the chromosome. Successful tagging of mRFP to the C terminus of Snf7 was verified by PCR analysis and fluorescence microscopy. The_ATG18-GFP_ and ATG2-GFP strains were generated as reported previously (9).

Plasmids for the expression of Vps34 (pKHR54) and Vps34N736K (pKHR60) in yeast cells have been described previously (11). The plasmid for the expression of Atg18 and Atg18(FTTG) in yeast cells was generated as follows. The genomic sequence covering the promoter, coding region, and 3′-untranslated region of ATG18 was amplified by PCR, digested with SpeI and SacI, and ligated into SpeI/SacI-digested pRS316, yielding the pMO101 plasmid. Point mutations generating amino acid substitutions (FRRG to FTTG at residues 284-287) were introduced in pMO101 using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), resulting in pATG18(FTTG). The plasmid for expression of ATG18-HA-GFP was generated as follows. The promoter, coding region, and 3′-untranslated region of ATG18 was amplified by PCR to have KpnI and XhoI, SalI and XhoI, and NotI and SacI sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends. The sequence coding3HA-GFP following a linker sequence was amplified by PCR from pOK5 (13) to have SalI and NotI sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. In pOK5, an SphI site was generated at the 3′-end of the HA sequence. These fragments were cloned into pRS316, resulting in pATG18HG. The_ATG18(FTTG)-HA-GFP_ plasmid was generated as follows. The region containing the mutated FTTG sequence was excised from pATG18(FTTG) by BglII and MroI digestion. The fragment replaced the corresponding BglII-MroI region of pATG18HG containing the FRRG motif, yielding pOK178. The_ATG18(FTTG)-HA-2_×FYVE plasmid was generated as follows. The 2_×_FYVE fragment with preceding linker sequence was amplified by PCR from pEGFP-2×FYVE (kind gift from Dr. H. Stenmark) such that SphI and NotI sites were generated at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The GFP sequence in pOK178 was excised with SphI and NotI, and the 2_×_FYVE fragment was inserted into that site, resulting in pOK180. Successful construction of plasmids was verified by sequencing and immunoblot analysis.

_Microscopy_—The intracellular localization of GFP- and mRFP-tagged proteins was observed using inverted fluorescence microscopes (IX-71 and IX-81; Olympus) equipped with cooled CCD cameras (CoolSNAP HQ; Nippon Roper). For the simultaneous observation of GFP and mRFP fusion proteins, cells were excited simultaneously with blue (Sapphire 488-20; Coherent) and yellow lasers (85-YCA-010; Melles Griot). A U-MNIBA2, from which the excitation filter was removed, was used for GFP visualization, and an FF593-Di02 dichroic mirror and an FF593-Em02 excitation filter (Semrock) were used to analyze mRFP. The accumulation of autophagic bodies was examined by phase-contrast microscopy (IX-71; Olympus). Images were acquired using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging) and processed using Adobe PhotoShop software (Adobe).

_Immunoblotting_—Immunoblotting was performed using anti-ApeI (kind gift from Dr. D. Klionsky), anti-Atg18, anti-HA (HA-7; Sigma), and affinity-purified anti-Atg2 (22) antibodies. Immunodetection utilized an ECL system (Amersham Biosciences) with a bioimaging analyzer (LAS1000; Fujifilm).

_Co-immunoprecipitation_—Cells were treated with rapamycin for 10 min and converted to spheroplasts. During the generation of spheroplasts, cells were maintained in rapamycin-containing buffers. The spheroplasts were lysed by osmotic shock and then solubilized for 30 min at 4 °C in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mm sorbitol, 150 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4 mm Pefabloc SC (Roche Applied Science), 40 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 40 μg/ml benzamidin, protease inhibitor mixture (Complete, EDTA-free; Roche Applied Sciences), and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (EDTA-free; Nakarai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan)). After the removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min. Supernatants were incubated with or without affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody at 4 °C for 2 h. Following the addition of Protein G-Sepharose beads, samples were incubated for an additional 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed four times with immunoprecipitation buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE.

_Gel Filtration_—Cells were treated with rapamycin and converted to spheroplasts, as described above. The spheroplasts were lysed by osmotic shock and then solubilized for 30 min at 4 °C in Gel-f buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4 mm Pefabloc SC (Roche Applied Science), 40 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 40 μg/ml benzamidin, protease inhibitor mixture (Complete, EDTA-free; Roche Applied Science), and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (EDTA-free; Nakarai Tesque)). After the removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was separated by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences). The column was equilibrated with Gel-f buffer without protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The supernatant (about 0.6 mg of protein in 70 μl) was applied to and eluted from the column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and 0.8-ml fractions were collected. The column was calibrated with both high and low molecular mass gel filtration protein standards (Amersham Biosciences) containing blue dextran (marker for the void fraction), thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), catalase (232 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), albumin (67 kDa), and ovalbumin (43 kDa).

RESULTS

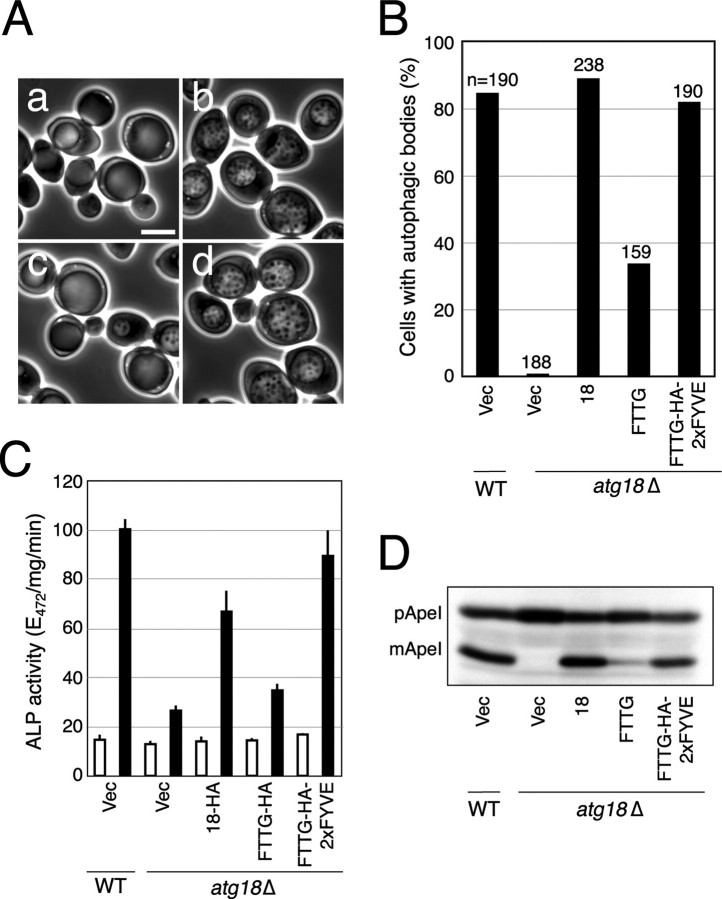

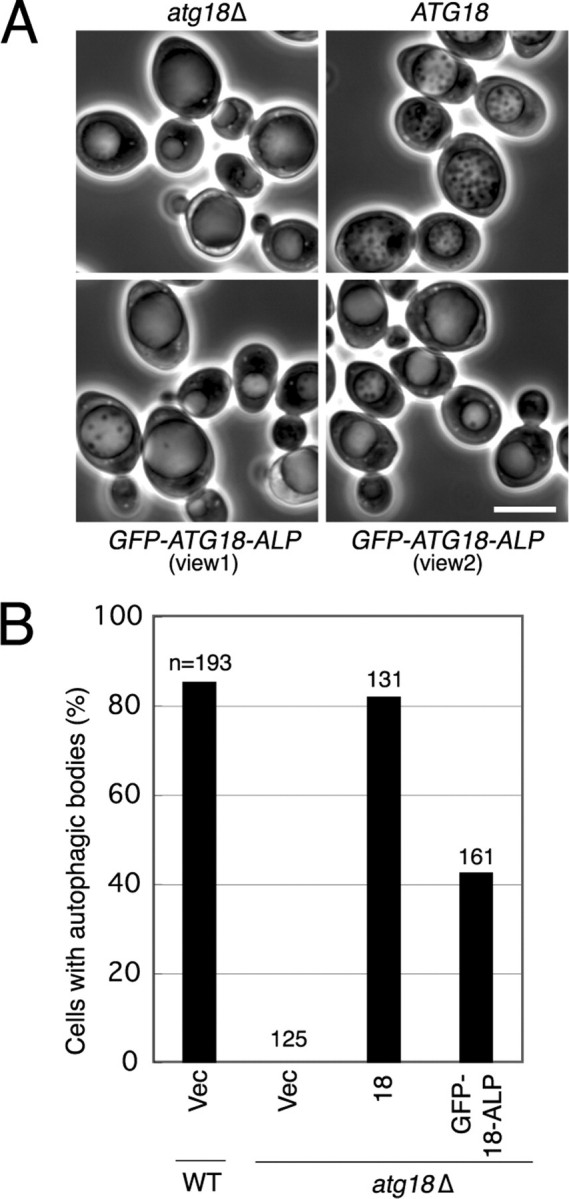

_PtdIns(3)P Binding of Atg18 and Autophagic Activity_—Previous studies have shown that PtdIns(3)P but not PtdIns(3,5)P2 is essential for autophagy (17). Atg18 is a candidate PtdIns(3)P effector, since it binds to PtdIns(3)P in vitro, and its localization to the PAS is dependent on Atg14, a subunit of the PtdIns 3-kinase complex (complex I) (9). To investigate the relationship between PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 and autophagy, we utilized an Atg18 variant, Atg18(FTTG), which harbors amino acid substitutions (FRRG to FTTG) in the putative phosphoinositide-binding motif and therefore is unable to bind to phosphoinositides (17,18). First, we examined the efficiency of autophagy in _atg18_Δ cells exogenously expressing Atg18(FTTG) by observing autophagic bodies accumulated in the vacuole. For the clear visualization of autophagic bodies, we used S (-NC) medium lacking both nitrogen and carbon sources, since cells cultured in this medium usually contain a single large central vacuole, which allows easier monitoring of autophagic bodies. In Atg18(FTTG) cells, the accumulation of autophagic bodies was severely reduced (Fig. 1, A and B). We next estimated autophagic activity by an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay. The ALP assay monitors the transport of cytoplasm into the vacuole via autophagy by measuring the activity of alkaline phosphatase that is artificially expressed in the cytosol as a pro form and transported into the vacuole via autophagy, where it is processed to the mature form. This assay has been shown to report autophagic activity quantitatively (23). As shown in Fig. 1_C_, Atg18(FTTG) cells had reduced autophagic activity. Since PtdIns(3,5)P2 is dispensable for autophagy (Fig. S1) (17), this defect probably arose from loss of binding to PtdIns(3)P rather than to PtdIns(3,5)P2, thus indicating that PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is required for full autophagic activity. The Cvt (cytoplasm tovacuole targeting) pathway is thought to be a type of selective autophagy that transports aminopeptidase I (ApeI) from the cytosol to the vacuole under nutrient-rich conditions. Progression of this pathway can be monitored by detecting the mature form of ApeI cleaved inside the vacuole. Similar to the case of nonselective autophagy induced by starvation, PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 was required for efficient progression of the Cvt pathway (Fig. 1_D_).

FIGURE 1.

PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is essential for full autophagic activity. A, BJ2168 atg18_Δ cells carrying empty vector (Vec) (a), ATG18 plasmid (b),ATG18(FTTG) plasmid (c), or_ATG18(FTTG)-HA-2_×_FYVE plasmid (d) were cultured in S (-NC) medium for 5 h. Autophagic bodies were observed by phase-contrast microscopy. B, frequency of cells with autophagic bodies was calculated. C, cells at logarithmic phase were cultured in SD (-N) medium for 4 h, and autophagic activity was measured by an ALP assay.Bars, STDEV. D, cells were collected at logarithmic phase. Cell lysates were prepared by the alkaline-trichloroacetic acid method and separated by SDS-PAGE. The pro and mature forms of ApeI were detected by immunoblotting with anti-ApeI antibody. WT, wild type.

To further confirm the requirement of Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding in autophagy, we employed an engineered form of Atg18 in which the 2×FYVE domain derived from mammalian Hrs was fused to Atg18(FTTG). The 2×FYVE domain has been demonstrated to bind specifically to PtdIns(3)P with high affinity both in vitro and in vivo (24). Interestingly, full autophagic activity was restored in _atg18_Δ cells expressing Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE (Fig. 1). The defect in the Cvt pathway was also suppressed by targeting Atg18(FTTG) to PtdIns(3)P-enriched sites by the 2×FYVE domain (Fig. 1_D_). These results led to the following conclusions. First, PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 is required for full activity of both nonselective autophagy under starvation conditions and the Cvt pathway under nutrient-rich conditions. Second, once tightly associated to PtdIns(3)P-enriched sites, Atg18 exerts its function in a manner that does not require Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding through the native site, since the Atg18(FTTG) variant was fully active when the 2×FYVE domain was fused to bypass the targeting step.

_Formation of Atg18-Atg2 Complex Irrespective of Binding to PtdIns(3)P_—We next used the Atg18(FTTG) variant to clarify which process is dependent on PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18. Atg18 is known to form a complex with Atg2 (9). To determine whether PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 is required for Atg18-Atg2 complex formation, co-immunoprecipitation analysis was performed using affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody. The Atg18(FTTG) variant was co-immunoprecipitated with Atg2 with similar efficiency to wild-type Atg18. Atg18 and Atg18(FTTG) were co-immunoprecipitated in a manner dependent both on the anti-Atg2 antibody and Atg2 (Figs. 2,A and B), confirming the specificity of this assay. Thus, PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is not necessary for Atg18-Atg2 complex formation. Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE was also co-immunoprecipitated with Atg2. Co-immunoprecipitation assays were also performed in_vps34_Δ cells expressing a PtdIns 3-kinase-deficient enzyme, Vps34N736K. Since Vps34 is the sole PtdIns 3-kinase in _S. cerevisiae, vps34_Δ cells with the Vps34N736K variant do not contain detectable PtdIns(3)P despite normal formation of PtdIns 3-kinase complexes (11,25). In Vps34N736K cells, Atg18 was also co-immunoprecipitated with Atg2 (Fig. 2_B_). Taken together, Atg18-Atg2 complex formation does not require PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18. Given the ability of Atg18(FTTG) to bind Atg2, it also seems unlikely that the amino acid substitutions at the FRRG motif affect the tertiary structure of Atg18, which is consistent with the fact that Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE can support normal autophagic activity (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 2.

Atg18-Atg2 complex formation is independent of PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18. _A, atg18_Δ cells expressing Atg18 variants were treated with rapamycin. The postsolubilization 100,000 × g supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with or without affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody (Ab). Precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody and anti-Atg18 serum. Signals shown were obtained on the same membrane with the same exposure time and processed equally. B, postsolubilization, 100,000 × g supernatants were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation with affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody. The precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with affinity-purified anti-Atg2 antibody and anti-Atg18 serum. C, cells were treated with rapamycin, and the postsolubilization 100,000 × g supernatants were subjected to gel filtration analysis. D, the signal intensity of each fraction shown in C was measured, and the percentage of the total was calculated. For the lower graph, see Fig. S2.

The Atg18-Atg2 complex was further analyzed by gel filtration. Cells were treated with rapamycin to induce autophagy, and their postsolubilization 100,000 × g supernatants were subjected to gel filtration analysis. Approximately 20-30% of Atg18-HA-GFP was eluted in the fractions corresponding to ∼500 kDa, whereas the remaining protein was mostly eluted in fractions around 150-200 kDa (Fig. 2,C and D). Since the elution buffer contained 1% Triton X-100, the exact size of the ∼500-kDa complex cannot be determined, and thus hereafter it is simply called the “Large complex.” The elution profile of Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP was similar to that of Atg18-HA-GFP. We also determined the elution patterns of Atg18 and Atg18(FTTG) without the HA-GFP tag. Both Atg18 and Atg18(FTTG) eluted as part of the Large complex and as monomers (Fig. S2). Thus, Atg18-HA-GFP and Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP eluting in the 150-200-kDa fraction probably represent dimers caused by interactions between GFP molecules (26,27). Atg2 was also eluted at fractions corresponding to ∼500 kDa, where the Large complex elutes (Fig. 2, C and_D_). Monomer Atg2, ∼170 kDa, was not detected. In_atg2_Δ cells, Atg18-HA-GFP and Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP were mostly absent from the Large complex and almost entirely eluted in the 150-200-kDa fractions (Fig. 2, C and_D_), indicating that Atg18 and Atg2 are components of the Large complex. Likewise, untagged Atg18 disappeared from the Large complex and was eluted mostly as a monomer in the absence of Atg2 (Figs. 2_D_ and S2). These results show that Atg18 and Atg2 reside in the Large complex, regardless of the PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18.

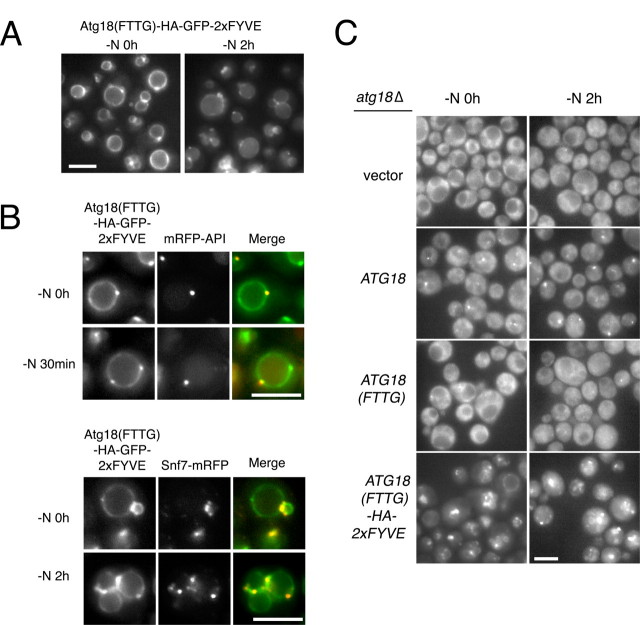

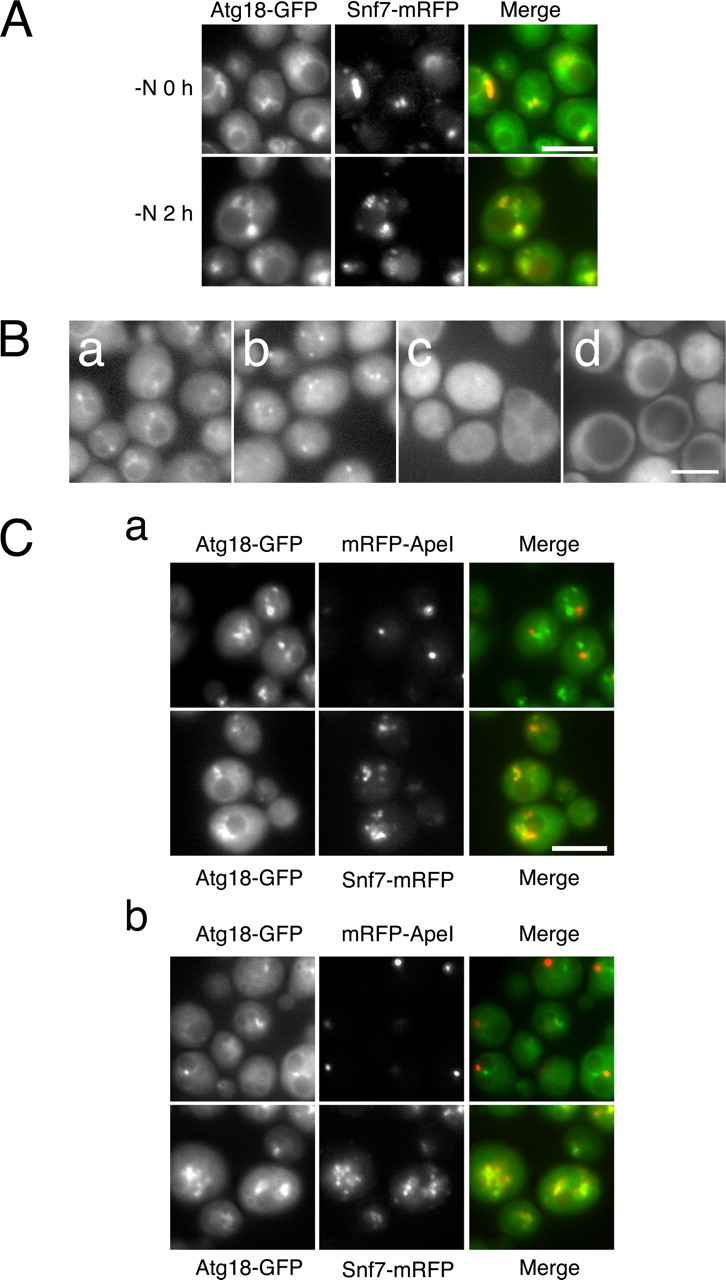

_Recruitment of Atg18-Atg2 Complex to Autophagic Membranes via PtdIns(3)P_—Atg18 is known to localize to the vacuolar membranes and perivacuolar punctate structures, including the PAS (9,28). On the vacuolar membrane, some Atg18-positive motile foci are observed (29). We carefully examined the localization of Atg18 to identify the perivacuolar punctate structures other than the PAS. We found that most of the Atg18-positive perivacuolar punctate structures were endosomes, since they were also labeled with an endosomal marker, Snf7-mRFP (Fig. 3_A_). Endosomal localization of Atg18 was seen both at logarithmic growth and under starvation conditions. In addition to endosomes, we also detected Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane and the PAS (data not shown) as reported previously. A substantial amount of Atg18 detached from the vacuolar membrane at 4 h of nitrogen starvation (Fig. 3_B_). At present, we cannot distinguish the PAS from isolation membranes or autophagosomes by fluorescent microscopy, since they are all represented only as fluorescent dots due to limitations of spatial resolution. Therefore, the PAS, isolation membranes, and autophagosomes will be hereafter referred to as autophagic membranes. Atg18(FTTG) was dispersed in the cytosol both at logarithmic growth and under starvation conditions (Fig. 3_B_). Occasionally, a faint signal was observed at autophagic membranes (data not shown). Likewise, Atg18 was dispersed in the cytosol in Vps34N736K cells. Therefore, localization of Atg18 to the membranes requires binding to phosphoinositides. Atg2 is also required for the localization of Atg18 to autophagic membranes, since Atg18 does not co-localize with ApeI, a PAS marker (9), in the absence of Atg2 (Fig. 3_C_). In contrast, endosomal localization of Atg18 does not require Atg2 both at logarithmic growth phase and under starvation conditions (Fig. 3_C_).

FIGURE 3.

Localization of Atg18. A, cells expressing Atg18-GFP and Snf7-mRFP at logarithmic phase (-N0h) and under starvation condition (-N2 h) were subjected to fluorescence microscopy. Atg18-GFP and Snf7-mRFP were excited and detected simultaneously (see “Experimental Procedures”). B, localization of Atg18-GFP was observed by fluorescence microscopy at logarithmic phase (a) and after 4 h of nitrogen starvation (b). Localization of Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP was observed after 4 h of nitrogen starvation (c). In d, Atg18-GFP was observed in _vps34_Δ cells expressing the Vps34N736K variant. C, Atg18-GFP was observed in_atg2_Δ cells expressing mRFP-ApeI or Snf7-mRFP, PAS and endosome marker, respectively, at logarithmic growth phase (a) and 2 h of nitrogen starvation (b). The GFP and mRFP signals were detected at the same time points as in A. Bars, 5 μm.

Next, we asked whether PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 is required for the proper localization of Atg2. In wild-type cells, Atg2 localized to autophagic membranes (Fig. 4_C_) (9). The localization of Atg2 to autophagic membranes was lost in _atg18_Δ cells expressing Atg18(FTTG), although a faint Atg2 signal was detected at the autophagic membranes in rare cases (Fig. 4_C_). These findings indicate that PtdIns(3)P-binding of Atg18 is required for the tight association of the Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes. Considering that Atg2 is required for the localization of Atg18 to autophagic membranes, it seems likely that tight association of Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes requires a synergistic effect of the Atg18-PtdIns(3)P interaction and an interaction between Atg2 and some factor(s) preexisting at autophagic membranes (see “Discussion”).

FIGURE 4.

Localization of Atg18-Atg2 complex is regulated by PtdIns(3)P. A, Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP-2×FYVE was monitored at logarithmic phase and under nitrogen starvation conditions. B, Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GFP-2×FYVE was observed simultaneously with mRFP-ApeI or Snf7-mRFP at logarithmic phase (-N0h) and under starvation condition (-N 30 min and 2h). C, Atg2-GFP was observed at logarithmic phase (-N0h) and after 2 h of nitrogen starvation (-N2h) in atg18_Δ cells carrying empty vector,ATG18 plasmid, ATG18(FTTG) plasmid, or_ATG18-HA-2_×_FYVE plasmid. Bars, 5 μm.

Fusion of HA-2×FYVE to Atg18(FTTG) restored localization to endosomes, vacuolar membranes, and autophagic membranes, as indicated by co-localization with mRFP-ApeI and Snif7-mRFP, markers for the PAS and endosomes, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Compared with the case of wild-type Atg18, signals on these membranes were clear, and cytosolic signals largely decreased, probably reflecting a high affinity of the 2×FYVE domain to PtdIns(3)P. The localization of Atg2 to autophagic membranes was also restored in _atg18_Δ cells expressing Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE (Fig. 4_C_). Localization of Atg2 to endosomes was seen in these cells; this is probably because most of the Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE was targeted to the membranes and excluded from the cytosol. Taken together, these data indicate that the process requiring Atg18-PtdIns(3)P interaction is tight association of the Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes.

_Relationship between Autophagic Activity and Atg18 on the Vacuolar Membrane_—Atg18 is also involved in regulation of vacuolar morphology. Localization of Atg18 to the vacuolar membrane is mediated by PtdIns(3,5)P2 but not by PtdIns(3)P, since Atg18 is not associated to the vacuolar membrane in the absence of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (17). Recently, it was shown that Atg18 located on the vacuolar membrane is responsible for the function of Atg18 in the regulation of vacuolar morphology (29). We then asked if PtdIns(3,5)P2 binding and following vacuolar membrane localization of Atg18 is responsible for normal autophagic activity in Atg18(FTTG) cells. We generated an Atg18 isoform in which GRAM domain derived from human myotubulalin (hMTM1) was fused to Atg18(FTTG)-HA. The GRAM domain of hMTM1 is known to be a PtdIns(3,5)P2-binding domain. In_atg18_Δ cells expressing the Atg18(FTTG)-HA-GRAM variant, autophagy was still severely affected (data not shown). It is likely that binding to PtdIns(3)P but not to PtdIns(3,5)P2 is required for full autophagic activity. We took another approach to examine the relationship between Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane and autophagy. Efe et al. (29) anchored GFP-Atg18 exclusively to the vacuolar membrane by fusing it at the C terminus to ALP, a vacuolar transmembrane protein. They showed that GFP-Atg18-ALP was functional in the regulation of vacuolar morphology but was not fully active in the Cvt pathway. We examined starvation-induced autophagy in _atg18_Δ cells expressing GFP-Atg18-ALP. Cells expressing GFP-Atg18-ALP had significantly reduced autophagic activity, suggesting that the Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane cannot support normal autophagic activity (Fig. 5). HA-Atg18-ALP yielded similar results (data not shown). This is consistent with the hypothesis that PtdIns(3,5)P2, which mediates the localization of Atg18 to the vacuolar membrane, is not essential for autophagy. The residual autophagic activity may result from a leakage of GFP-Atg18-ALP from the vacuolar membrane under starvation conditions (Fig. S3).

FIGURE 5.

Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane cannot support full activity of bulk autophagy. _A, atg18_Δ cells expressing Atg18 or GFP-Atg18-ALP were cultured in S (-NC) medium for 6 h, and autophagic bodies were observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Bar, 5 μm. B, the frequency of cells containing autophagic bodies was calculated.WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Atg18-PtdIns(3)P Association Is Required for Full Activity of Autophagy and the Cvt Pathway_—Atg18 has been shown to interact with PtdIns(3)P in vitro. However, the significance of phosphoinositide-binding of Atg18 during autophagy has not been shown clearly. We herein dissected the function of Atg18 in autophagy from the viewpoint of phosphoinositide binding and found that PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is essential for full activity of both autophagy and the Cvt pathway. Krick_et al. (18) reported that the Cvt pathway was completely blocked in Atg18(FTTG) cells, whereas autophagy was only slightly affected (18). From this result, they suggested that the function of Atg18 in the two pathways could be separated by the requirement for PtdIns(3)P binding. Here, we obtained results slightly different from their work. We found that the Cvt pathway was not completely blocked even under nutrient-rich conditions in Atg18(FTTG) cells, although a significant defect was seen. We also found that starvation-induced nonselective autophagy was significantly reduced in Atg18(FTTG) cells. It is likely that PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is not essential for the minimum level of autophagy or the Cvt pathway but is required for the efficient progression of both pathways. Thus, we prefer the idea that the function of the Atg18-PtdIns(3)P interaction is similar in both pathways rather than distinctive.

The residual autophagic activity in Atg18(FTTG) cells may be conferred by low remaining localization of the Atg18(FTTG)-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes (Figs. 3 and4), which might arise from a protein-protein interaction (see below). It is also possible that Atg2 has a weak affinity to the lipid enriched at autophagic membranes. Interestingly,_atg18_Δ cells expressing the Atg18(FTTG) variant could not maintain a normal vacuolar morphology and were indistinguishable with knock-out cells (Fig. S4). The extent of dependence on the Atg18-phosphoinositide interaction might differ between these two processes.

_Dissection of Atg18 Functions during Autophagy_—In_atg18_Δ cells expressing the Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE fusion protein, normal activity of the autophagy and Cvt pathways was restored. One important conclusion from this result is that PtdIns(3)P binding by Atg18 through its native site is only for membrane targeting but not for any subsequent functional activities of Atg18. Phosphoinositide binding is known to induce conformational changes in some effector proteins. For example, binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2 evokes conformational changes in N-WASP that expose functional domains required for cell movement (30). Our results suggest that PtdIns(3)P does not regulate Atg18 function in such an allosteric manner during autophagy. Although we do not exclude the possibility that there remains another PtdIns(3)P binding site that induces a conformational change in Atg18, such a putative site is not tightly associated with autophagic activity.

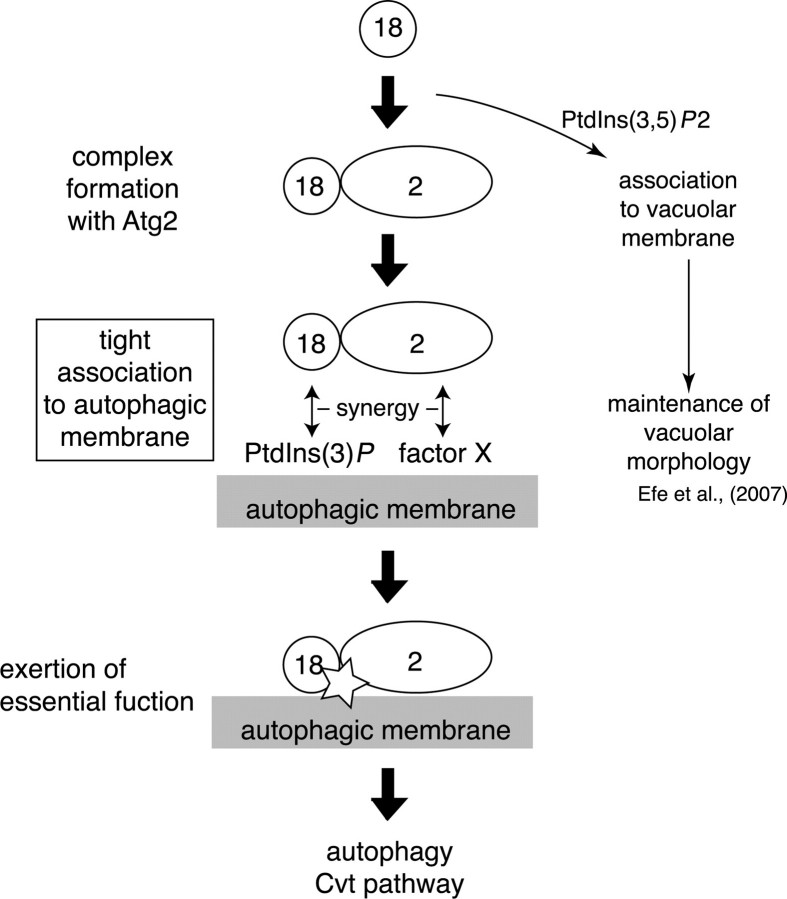

Co-immunoprecipitation and gel filtration analyses indicated that formation of a protein complex, including Atg18 and Atg2, was independent of Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding. The Atg18-Atg2 complex was retained even in PtdIns 3-kinase-deficient Vps34N736K cells; nevertheless, Atg18 was thoroughly dispersed in the cytosol. Thus, a stable Atg18-Atg2 complex can be formed in the cytosol and does not seem to require membranes as a scaffold. Gel filtration analysis of cells under nutrient-rich conditions gave elution profiles of Atg18 and Atg2 similar to those of autophagy-induced cells (data not shown). These results suggest that the Atg18-Atg2 complex is formed constitutively and functions in both autophagy and the Cvt pathway. On the other hand, Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding was required for the localization of the Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes, consistent with the recent demonstration that PtdIns(3)P is highly enriched on isolation membranes and autophagosomes (16). In addition to PtdIns(3)P, Atg2 is required for the localization of Atg18 to autophagic membranes (Fig. 3_C_) (9). Atg2 is known to bind to Atg9 (31) and potentially to some other proteins existing at autophagic membranes.3 These protein-protein interactions are probably required for the proper targeting of the Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes. Cooperative recruitment by protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions may assure the fidelity of the localization of the Atg18-Atg2 complex. As mentioned above, Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding is not directly involved in the function of Atg18-Atg2 complex on the autophagic membranes; instead, it is involved indirectly in that function through associating Atg18-Atg2 complex to autophagic membranes. These processes are summarized in Fig. 6.

FIGURE 6.

Dissection of Atg18-related processes during autophagy. A summary of Atg18-related processes during autophagy is shown. The process that requires PtdIns(3)P binding of Atg18 is boxed. Atg18 can form a protein complex with Atg2 independent of binding to PtdIns(3)P. The Atg18-Atg2 complex associates with autophagic membranes; this depends on a cooperation of Atg18-PtdIns(3)P binding and Atg2-X (existing at autophagic membrane) interaction. On the autophagic membranes, the Atg18-Atg2 complex exerts an unknown function(s), which does not require direct interaction between PtdIns(3)P and Atg18. These processes are involved in starvation-induced autophagy and the Cvt pathway. The exact components and stoichiometry of the Atg18-Atg2 complex are to be clarified in the future. Direction of the complex toward the membrane is also unknown at present. Binding to PtdIns(3,5)P2 (and to some vacuolar protein component) is required for Atg18 to localize to the vacuolar membrane, where it functions to maintain vacuolar homeostasis (29).

What is the function of Atg18 after localizing to autophagic membranes? The simplest answer would be “none”: the only function of Atg18 is to concentrate Atg2 at autophagic membranes by binding to PtdIns(3)P. This possibility was examined by fusing the 2×FYVE domain to Atg2 to bypass Atg18 in targeting Atg2 to PtdIns(3)P-enriched autophagic membranes._atg18_Δ_atg2_Δ double knock-out cells expressing Atg2-HA-2×FYVE had no autophagic activity (data not shown). Thus, this possibility appears not to be true. We also tested the possibility that the function of Atg2 is to concentrate Atg18 on autophagic membranes. Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE was expressed in_atg18_Δ_atg2_Δ double knock-out cells, and autophagic activity was examined. Although Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE is functional in _atg18_Δ single knock-out cells, it could not restore autophagic activity in _atg18_Δ_atg2_Δ double knock-out cells (data not shown). Thus, the Atg18-Atg2 complex seems to have an additional function at autophagic membranes. Atg18 and Atg2 are proposed to be involved in the release of a trans-membrane protein, Atg9, from the PAS to an unknown peripheral pool (32). However, Atg9 accumulates to high levels in most of the atg knock-out cells (9), and thus it remains unclear whether the Atg18-Atg2 complex is directly involved in this process. We recently found that PtdIns(3)P is highly enriched on autophagic membranes (16). Notably, PtdIns(3)P was observed preferentially on the inner surfaces of isolation membranes and autophagsomes compared with the outer surface. In addition, PtdIns(3)P was enriched near the elongating tips of isolation membranes. From such information, one would speculate that the Atg18-Atg2 complex may function in generating negative curvature at the inner surface of isolation membranes. If so, most of the Atg18-Atg2 complex should eventually detach from the inner membranes, since Atg18 and Atg2 are not so massively transported into the vacuole (Fig. 4). Alternatively, it would also be possible that the Atg18-Atg2 complex functions around the elongating tips of isolation membranes to construct and maintain the edges of the isolation membranes. However, current understanding of the properties of the Atg18-Atg2 complex, particularly Atg2, is quite limited. The most important future issue is to characterize these proteins in detail by structural approaches in combination with systematic mutagenesis and in vitro assays.

_Atg18 in Autophagy and Regulation of Vacuolar Morphology_—Atg18 is involved in the regulation of vacuolar morphology as well as autophagy. Recent work demonstrated that Atg18 on vacuolar membranes is responsible for this function. The vacuolar membrane localization of Atg18 is mediated by PtdIns(3,5)P2 and protein components, such as Vac7 (29). Given that PtdIns(3,5)P2 is dispensable for autophagy and that Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane cannot fully function in autophagy (Fig. 5), the two Atg18-related processes, autophagy and vacuolar homeostasis, may not to be directly linked. However, there is a significant similarity of Atg18 action in these distinct processes. First, interaction between Atg18 and phosphoinositide is required for the proper localization of Atg18; Atg18-PtdIns(3)P interaction is required for localization to autophagic membranes, and Atg18-PtdIns(3,5)P2 interaction is required for localization to vacuolar membranes. Second, protein components act synergistically with phosphoinositides in recruiting Atg18 to the correct membranes: Atg2 is required for the localization of Atg18 to autophagic membranes, and Vac7 is required for the localization of Atg18 to vacuolar membranes. Third, after localizing to the proper sites, Atg18 exerts a function that does not require direct binding to phosphoinositides; mutant Atg18 proteins that cannot bind phosphoinositides are fully active in both processes if they are targeted to the proper membrane (Fig. 1) (29). Similarly, Atg18(FTTG)-HA-2×FYVE could restore normal vacuole morphology in_atg18_Δ cells, because the fusion protein can bypass the normal PtdIns(3,5)P2-dependent targeting of Atg18 by the interaction between the FYVE domain and PtdIns(3)P on vacuolar membranes (Fig. S4). Thus, Atg18 uses similar modes for localization and function in these distinct biological processes. In this framework, Atg18 is sorted to specific functions by associating with distinct phosophoinositides and proteins, thereby locating itself to the correct place.

Another notable result is that the Atg18-GFP signal on vacuolar membranes became less intense under nitrogen starvation conditions (Fig. 3_B_). As described above, Atg18 on the vacuolar membrane cannot fully function in autophagy (Fig. 5). It will be interesting to determine whether some mechanism leads to the release of Atg18 from vacuolar membranes under starvation conditions, enabling Atg18 to function preferentially in autophagy. Monitoring of Vac7 behavior, Fab1 activity, and the level of PtdIns(3,5)P2 under nitrogen starvation conditions is an important future step.

Atg18 is abundant on endosomes. Endosomal localization of Atg18 was shown to be dependent on the putative phosphoinositide-binding motif, the FRRG sequence, but independent of Atg2. At present, we do not know if an unknown protein synergistically acts with phosphoinositide to target Atg18 to endosomes. Understanding of how Atg18 functions after localizing to endosomes is also limited. The localizing mechanism and function of Atg18 on endosomes is an important future issue.

In this paper, we showed that one of the functions of PtdIns(3)P in autophagy is to concentrate Atg18-Atg2 complexes at autophagic membranes. However, we believe that this is not the sole function of PtdIns(3)P in autophagy. We previously showed that proper localization of the Atg12-Atg5/Atg16 complex and Atg8-phosphatidylethanolamine is dependent on PtdIns 3-kinase complex I (10). Since localization of these proteins is not dependent on Atg18, and vice versa, PtdIns(3)P probably recruits these proteins and the Atg18-Atg2 complex independently. It is also possible that PtdIns(3)P is involved directly in generating a curvature of isolation membranes without the assistance of PtdIns(3)P binding effectors. We are now investigating these possibilities, which will provide additional insights into the mechanism of autophagosome formation.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Harald Stenmark for providing the 2×FYVE plasmids, Dr. Roger Y. Tsien for mRFP plasmid, Dr. Daniel J. Klionsky for anti-ApeI antibody, Dr. Tadaomi Takenawa for GRAM plasmid, Drs. Nobuo Noda and Fuyuhiko Inagagi for recombinant Atg18, and Dr. Scott D. Emr for GFP-Atg18-ALP plasmid. We also thank R. Ichikawa, C. Kondo, and the NIBB Center for Analytical Instruments for technical support.

*

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research 15002012 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “_advertisement_” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available athttp://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S4.

Footnotes

2

The abbreviations used are: PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol; PAS, preautophagosomal structure; PtdIns(3)P, phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate; PtdIns(3,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate; HA, hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescent protein; mRFP, monomeric red fluorescent protein; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

3

K. Obara, K. Niimi, and Y. Ohsumi, unpublished result.

References

- 1.Ohsumi, Y. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2 211-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima, N. (2007) Genes Dev. 21 2861-2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba, M., Takeshige, K., Baba, N., and Ohsumi, Y. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 124 903-913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizushima, N., Yamamoto, A., Hatano, M., Kobayashi, Y., Kabeya, Y., Suzuki, K., Tokuhisa, T., Ohsumi, Y., and Yoshimori, T. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152 657-667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshige, K., Baba, M., Tsuboi, S., Noda, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 119 301-311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukada, M., and Ohsumi, Y. (1993) FEBS Lett. 333 169-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thumm, M., Egner, R., Koch, B., Schlumpberger, M., Straub, M., Veenhuis, M., and Wolf, D. H. (1994) FEBS Lett. 349 275-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klionsky, D. J., Cregg, J. M., Dunn, W. A., Jr., Emr, S. D., Sakai, Y., Sandoval, I. V., Sibirny, A., Subramani, S., Thumm, M., Veenhuis, M., and Ohsumi, Y. (2003) Dev. Cell. 5 539-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki, K., Kubota, Y., Sekito, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (2007) Genes Cells 12 209-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petiot, A., Ogier-Denis, E., Blommaart, E. F., Meijer, A. J., and Codogno, P. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 992-998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kihara, A., Noda, T., Ishihara, N., and Ohsumi, Y. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152 519-530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki, K., Kirisako, T., Kamada, Y., Mizushima, N., Noda. T., and Ohsumi, Y. (2001) EMBO J. 20 5971-5981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obara, K., Sekito, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 1527-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown, W. J., DeWald, D. B., Emr, S. D., Plutner, H., and Balch, W. E. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130 781-796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson, H. W. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130 797-805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obara, K., Noda, T., Niimi, K., and Ohsumi, Y. (2008) Genes Cells 13 537-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dove, S. K., Piper, R. C., McEwen, R. K., Yu, J. W., King, M. C., Hughes, D. C., Thuring, J., Holmes, A. B., Cooke, F. T., Michell, R. H., Parker, P. J., and Lemmon, M. A. (2004) EMBO J. 23 1922-1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krick, R., Tolstrup, J., Appelles, A., Henke, S., and Thumm, M. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 4632-4638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson, J. S., Klionsky, D. J., Banta, L. M., and Emr, S. D. (1988) Mol. Cell Biol. 8 4936-4948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser, C., Michaelis, S., and Mitchell, A. (1994) Methods in Yeast Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- 21.Campbell, R. E., Tour, O., Palmer, A. E., Steinbach, P. A., Baird, G. S., Zacharias, D. A., and Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 7877-7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shintani, T., Suzuki, K., Kamada, Y., Noda, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30452-30460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noda, T., Matsuura, A., Wada, Y., and Ohsumi, Y. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 210 126-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillooly, D. J., Morrow, I. C., Lindsay, M., Gould, R., Bryant, N. J., Gaullier, J. M., Parton, R. G., and Stenmark, H. (2000) EMBO J. 19 4577-4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stack, J. H., DeWald, D. B., Takegawa, K., and Emr, S. D. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129 321-334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, F., Moss, L. G., and Phillips, G. N., Jr. (1996) Nat. Biotechnol. 14 1246-1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zacharias, D. A., Violin, J. D., Newton, A. C., and Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Science 296 913-936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strømhaug, P. E., Reggiori, F., Guan. J., Wang, C. W., and Klionsky, D. J. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15 3553-3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Efe, J. A., Botelho, R. J., and Emr, S. D. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 4232-4244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takenawa, T., and Miki, H. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114 1801-1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, C. W., Kim, J., Huang, W. P., Abeliovich, H., Strømhaug, P. E., Dunn, W. A., Jr., and Klionsky, D. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30442-30451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reggiori, F., Tucker, K. A., Strømhaug, P. E., and Klionsky, D. J. (2004) Dev. Cell 6 79-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirisako, T., Baba, M., Ishihara, N., Miyazawa, K., Ohsumi, M., Yoshimori, T., and Ohsumi, Y. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 197 435-466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Data