NOTCH1 mutations in +12 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) confer an unfavorable prognosis, induce a distinctive transcriptional profiling and refine the intermediate prognosis of +12 CLL (original) (raw)

Abstract

Trisomy 12, the third most frequent chromosomal aberration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), confers an intermediate prognosis. In our cohort of 104 untreated patients carrying +12, NOTCH1 mutations occurred in 24% of cases and were associated to unmutated IGHV genes (_P_=0.003) and +12 as a sole cytogenetic abnormality (_P_=0.008). NOTCH1 mutations in +12 CLL associated with an approximately 2.4 fold increase in the risk of death, a significant shortening of survival (P<0.01) and proved to be an independent predictor of survival in multivariate analysis. Analogous to +12 CLL with TP53 disruption or del(11q), NOTCH1 mutations in +12 CLL conferred a significantly worse survival compared to that of +12 CLL with del(13q) or +12 only. The overrepresentation of cell cycle/proliferation related genes of +12 CLL with NOTCH1 mutations suggests the biological contribution of NOTCH1 mutations to determine a poor outcome. NOTCH1 mutations refine the intermediate prognosis of +12 CLL.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, NOTCH1 mutations, trisomy 12, prognosis, gene expression profile

Introduction

Trisomy 12 represents the third most frequent chromosomal aberration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (15–20% of cases) and often (approx. 60% of cases) occurs as the sole cytogenetic lesion.1,2 Within the hierarchical model of genetic subgroups commonly used in clinical practice, +12 as single aberration confers an intermediate prognostic risk, with a median time to progression of 33 months and a median overall survival (OS) of 114 months.1

The NOTCH1 gene has been shown to have an essential biological role in hematopoiesis.3 Following the pivotal study that identified NOTCH1 mutations in CLL and provided initial evidence on the unfavorable clinical outcome associated with NOTCH1 alterations,4 two independent studies of the CLL coding genome have recently identified activating mutations of the NOTCH1 gene in approximately 10% of CLL at diagnosis.5,6 The prevalence of NOTCH1 mutations increases with disease aggressiveness.5 At diagnosis, NOTCH1 mutations show an adverse impact on outcome, confirmed in at least four series,4–7 and act independently of other clinico-biological features, including TP53 disruption.7 Among CLL cytogenetic subgroups, NOTCH1 mutations are distributed in a mutually exclusive fashion with TP53 disruption and are enriched in CLL carrying +12, where they recur in approximately 25% of patients.7

Based on the emerging association between NOTCH1 alterations and +12, we investigated NOTCH1 mutations in a series of untreated +12 CLL. We observed that in these patients, NOTCH1 mutations: i) cluster within cases with no additional cytogenetic abnormalities; ii) induce a particular transcriptional profile; and iii) refine outcome prediction.

Design and Methods

Patients

This multicenter study evaluated 104 patients carrying +12: 54 were males and 50 females, with a median age of 65 years (interquartile range 56–72). All cases satisfied the IWCLL diagnostic criteria for CLL8 and were selected on the basis of: i) untreated disease; ii) availability of biological material; and iii) presence of +12, independent of additional chromosomal abnormalities.

Patients gave their informed consent to blood collection and biological analyses, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Policlinico Umberto I, “La Sapienza” University of Rome (n. 2182/16.06.2011) and of the Ospedale Maggiore della Carità, Novara, northern Italy, associated with the Amedeo Avogadro University of Eastern Piedmont (protocol code 59/CE; study n. CE 8/11).

Lymphocyte morphology, immunophenotype, FISH analysis, IGHV and TP53 sequencing were performed as previously described.9

Mutation analysis of NOTCH1

The NOTCH1 (exon 34; RefSeq NM_017617.2) mutation hotspot previously identified in CLL7 was analyzed by direct sequencing of genomic DNA extracted from blood mononuclear cells. Purified amplicons were subjected to conventional DNA Sanger sequencing using the ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The presence of NOTCH1 c.7544_7545delCT alleles was also investigated by ARMS PCR. Further details are reported in the Online Supplementary Design and Methods.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of initial presentation to the date of death (event) or last follow up (censoring). Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Further details are reported in the Online Supplementary Design and Methods.

Gene expression profile analysis

For oligonucleotide array analysis, the HGU133 Plus 2.0 gene chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used. Sample preparation and microarray processing were performed as previously described.10 Further details are reported in the Online Supplementary Design and Methods.

Results and Discussion

Frequency and distribution of NOTCH1 mutations in +12 CLL

NOTCH1 mutations occurred in 25 of the 104 untreated CLL with +12 investigated (24%) (Table 1A), were represented in all cases by frameshift deletions, including the c.7544_7545delCT in 22 of 25 (88%) cases, and preferentially associated with use of unmutated IGHV genes (84%, _P_=0.003). NOTCH1 mutations occurred independent of gender, thus suggesting that NOTCH1 mutations might be an important marker of unfavorable prognosis in both male and female CLL patients.

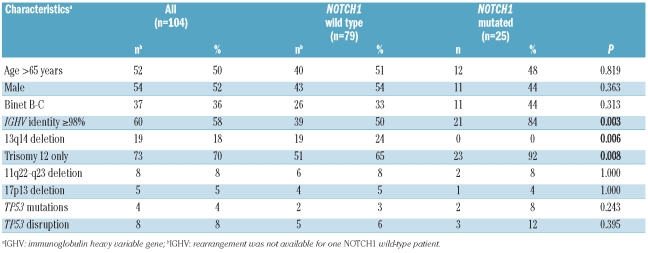

Table 1A.

Characteristics of CLL patients harboring +12 according to the NOTCH1 mutation status.

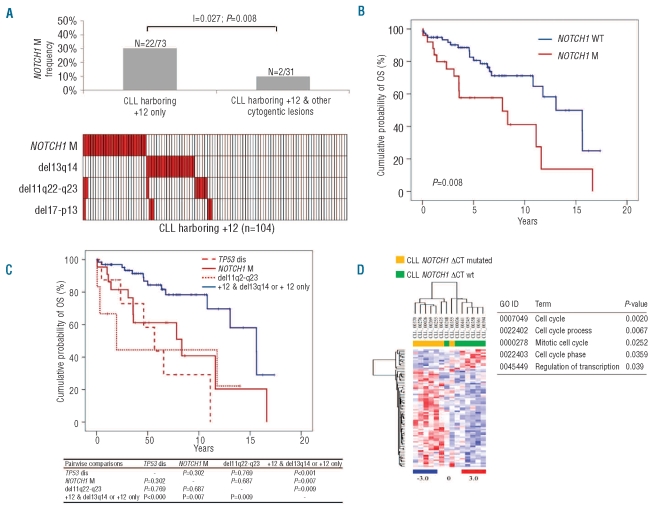

Trisomy 12 occurred as an isolated chromosomal abnormality in 73 of 104 (70%) cases, while it was associated to other cytogenetic abnormalities in 31 of 104 (30%) cases (Figure 1A). Mutual information analysis revealed a clustering of NOTCH1 mutations among CLL harboring +12 as a sole abnormality (22 of 73, 30%) compared to patients harboring +12 in addition to other cytogenetic lesions (2 of 31, 6%) (I=0.027; _P_=0.008) (Figure 1A). Consistently, +12 CLL harboring NOTCH1 mutations carried deletion 13q14 only exceptionally (0 of 19). Consistent with pivotal observations,5,7 also in +12 CLL, NOTCH1 mutations distributed in a mutually exclusive fashion with deletions of 17p13 and 11q22-q23 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Distribution of NOTCH1 mutations among genetic subgroups of +12 CLL. (B) Overall survival according to NOTCH1 mutation status in +12 CLL. (C) Hierarchical stratification of overall survival according to genetic lesions in +12 CLL. (D) Comparison between NOTCH1 mutated and NOTCH1 wt CLL samples. Relative levels of gene expression are depicted with a color scale: red represents the highest level of expression and blue represents the lowest level. The table reports the functional annotation analysis, performed using the DAVID database, of differentially expressed genes between NOTCH1 mutated and NOTCH1 wt CLL. The biological processes reported are ordered according to their P value.

This extended cohort corroborates the high prevalence of NOTCH1 mutations in +12 CLL, where the overall frequency of NOTCH1 mutations in +12 patients consistently ranges from 24.5 to 28.6%.7,11 Furthermore, +12 patients harboring NOTCH1 mutations prevalently belong to aggressive cases, i.e. cases with an unmutated IGHV gene status, in line with recent findings,7,11 and expression of CD38 (NOTCH1 mutated/CD38 positive, n=20 of 25 (80.0%) vs. NOTCH1 wild-type/CD38 positive, n=39 of 77 (50.6%) (_P_=0.010).

At variance, no difference emerged in the distribution of ZAP-70 positivity (NOTCH1 mutated/ZAP-70 positive, n=15 of 24 (62.5%) vs. NOTCH1 wild-type/ZAP-70 positive, n=34 of 77 (44.2%) (P=0.116).

Finally, the analysis of this specific cohort of patients showed an enrichment of NOTCH1 mutations in CLL harboring+12 as sole cytogenetic abnormality.

NOTCH1 mutations and overall survival in +12 CLL

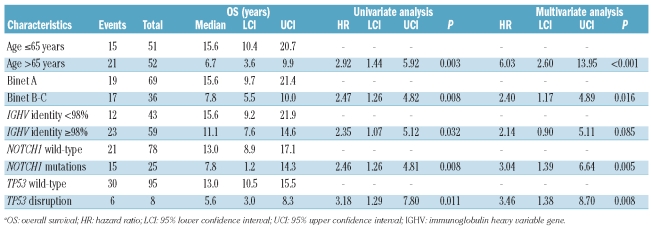

After a median follow up of seven years, 36 of 103 evaluable patients had died, for a median OS of 11.6 years (95% CI: 10.4–12.7). By univariate analysis, the crude impact of NOTCH1 mutations on survival in +12 CLL was an approximately 2.4 fold increase in the hazard of death (HR: 2.46; 95% CI: 1.26–4.81) and a significant shortening of OS (P<0.01) (Table 1B; Figure 1B). Other variables associated with shorter OS were age, Binet stage, IGHV mutation status and TP53 disruption.

Table 1B.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival in CLL patients harboring +12a.

Multivariate analysis selected NOTCH1 mutations as an independent risk factor of OS (HR: 3.04; 95% CI: 1.39–6.64; P<0.01), after adjusting for age (> vs. ≤65 years), Binet stage (B-C vs. A), IGHV mutation status and TP53 disruption by mutation and/or deletion. NOTCH1 mutations, 13q14 deletion, 11q22-q23 deletion and TP53 status were used to build a hierarchical model of genetic subgroups to predict OS in CLL with +12. The outcome of +12 CLL with NOTCH1 mutations was poor, similar to cases with +12 and TP53 disruption or 11q22-q23 deletion and significantly worse than patients with +12 as an isolated abnormality or plus 13q14 deletion (Figure 1C).

NOTCH1 mutations represent, therefore, an independent adverse prognostic factor of OS among +12 CLL, providing a new genetic prognostic stratification of patients with this intermediate risk marker.

Gene expression profiling of +12 CLL with NOTCH1 mutations

To understand whether NOTCH1 mutations induced a distinctive transcriptional profile in +12 CLL, we compared 7 NOTCH1 mutated vs. 7 NOTCH1 wild-type cases in a cohort of patients carrying +12 (Online Supplementary Table S1).

This analysis showed that NOTCH1 mutated cases formed a tight clustering (Figure 1D), with 2 patients incorrectly placed. Of these, one later developed a TP53 mutation and a myelodysplastic syndrome (CLL_00248, Online Supplementary Table S1).

Sixty-five differentially expressed genes (Online Supplementary Table S2) were selected, the majority being upmodulated in NOTCH1 mutated samples. DAVID functional annotation analysis highlighted an overrepresentation of cell cycle related genes, indicating that NOTCH1 mutations induce a proliferative advantage that might explain the clinically aggressive behavior (Figure 1D). We also observed significantly higher levels of IgM expression in NOTCH1 mutated cases. It is known that IgM expression is higher in cells with increased ability to respond to external stimuli,12,13 indicating that the NOTCH1 mutated clone might survive and expand also thanks to these interactions. Intriguingly, approximately 30% of the upregulated transcripts were located on chromosome 12. This might be due to the fact that +12 was present as a single alteration in all NOTCH1 mutated cases, whereas in the NOTCH1 wild-type subgroup the scenario was more complex, with 3 cases displaying only +12 and 4 cases one or more additional chromosomal aberrations.

Among the transcripts previously reported to be associated with a +12 signature, we confirmed the upregulation of ANAPC5, GLIPR1, TIMELESS and SLC2A6.14,15

In summary, this study highlights that NOTCH1 mutations in +12 CLL: i) preferentially cluster with cases harboring +12 as sole genetic abnormality; ii) account for 24% of cases and are more frequently detected in cases with unfavorable biological markers; iii) associate with a particular gene expression profile; iv) predict a poor outcome, stratifying +12 CLL in two distinct subgroups; and v) are not associated with TP53 disruption or 11q deletion, thus making them even more useful in a genetic hierarchical prognostic model, given their mutual exclusivity. This observation sheds light on the heterogeneous clinical course of +12 CLL patients and allows us to refine the intermediate prognostic risk of this chromosomal lesion. The transcriptional profile characterized by an overrepresentation of genes involved in cell cycle and proliferation suggests the potential biological contribution of NOTCH1 mutations in determining the aggressive behavior of the disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AIRC (to RF) and AIRC, Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology, 5 × 1000, n. 10007, Milan, Italy (to GG and to RF), Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino, Italy, Fondazione per le Biotecnologie, Torino, Italy, Fondazione Buzzati-Traverso, Pavia, Italy, Progetto FIRB-Programa “Futuro in Ricerca” 2008 (to DR), PRIN 2008 (to GG) and 2009 (to DR), MIUR, Rome, Italy, Progetto Giovani Ricercatori 2008 (to DR), Ministero della Salute, Rome, Italy, and Novara-AIL Onlus (to GG), Novara, Italy.

Footnotes

The online version of this article has a Supplementary Appendix.

Authorship and Disclosures

The information provided by the authors about contributions from persons listed as authors and in acknowledgments is available with the full text of this paper at www.haematologica.org.

Financial and other disclosures provided by the authors using the ICMJE (www.icmje.org) Uniform Format for Disclosure of Competing Interests are also available at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Kröber A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(26):1910–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matutes E, Oscier D, Garcia-Marco J, Ellis J, Copplestone A, Gillingham R, et al. Trisomy 12 defines a group of CLL with atypical morphology: correlation between cytogenetic, clinical and laboratory features in 544 patients. Br J Haematol. 1996;92(2):382–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milner LA, Bigas A. Notch as a mediator of cell fate determination in hematopoiesis: evidence and speculation. Blood. 1999;93(8):2431–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sportoletti P, Baldoni S, Cavalli L, Del Papa B, Bonifacio E, Ciurnelli R, et al. NOTCH1 PEST domain mutation is an adverse prognostic factor in B-CLL. Br J Haematol. 2010;151(4):404–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabbri G, Rasi S, Rossi D, Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Ma J, et al. Analysis of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia coding genome: role of NOTCH1 mutational activation. J Exp Med. 2011;208(7):1389–401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, Conde L, Ordóñez GR, Villamor N, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475(7354):101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi D, Rasi S, Fabbri G, Spina V, Fangazio M, Forconi F, Marasca R, et al. Mutations of NOTCH1 are an independent predictor of survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(2):521–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, et al. International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;112(13):5259–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Giudice I, Mauro FR, De Propris MS, Santangelo S, Marinelli M, Peragine N, et al. White blood cell count at diagnosis and immunoglobulin variable region gene mutations are independent predictors of treatment-free survival in young patients with stage A chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96(4):626–30. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.028779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiaretti S, Tavolaro S, Marinelli M, Messina M, Del Giudice I, Mauro FR, et al. Evaluation of TP53 mutations with the AmpliChip p53 research test in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: correlation with clinical outcome and gene expression profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(4):263–74. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balatti V, Bottoni A, Palamarchuk A, Alder H, Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ, et al. NOTCH1 mutations in CLL associated with trisomy 12. Blood. 2012;119(2):329–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mockridge CI, Potter KN, Wheatley I, Neville LA, Packham G, Stevenson FK. Reversible anergy of sIgM-mediated signaling in the two subsets of CLL defined by VH-gene mutational status. Blood. 2007;109(10):4424–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarini A, Chiaretti S, Tavolaro S, Maggio R, Peragine N, Citarella F, et al. BCR ligation induced by IgM stimulation results in gene expression and functional changes only in IgV H unmutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells. Blood. 2008;112(3):782–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haslinger C, Schweifer N, Stilgenbauer S, Döhner H, Lichter P, Kraut N, et al. Microarray gene expression profiling of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia sub-groups defined by genomic aberrations and VH mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(19):3937–49. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porpaczy E, Bilban M, Heinze G, Gruber M, Vanura K, Schwarzinger I, et al. Gene expression signature of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with Trisomy 12. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39(7):568–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]