MpeR Regulates the mtr Efflux Locus in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Modulates Antimicrobial Resistance by an Iron-Responsive Mechanism (original) (raw)

Abstract

Previous studies have shown that the MpeR transcriptional regulator produced by Neisseria gonorrhoeae represses the expression of mtrF, which encodes a putative inner membrane protein (MtrF). MtrF works as an accessory protein with the Mtr efflux pump, helping gonococci to resist high levels of diverse hydrophobic antimicrobials. Regulation of mpeR has been reported to occur by an iron-dependent mechanism involving Fur (ferric uptake regulator). Collectively, these observations suggest the presence of an interconnected regulatory system in gonococci that modulates the expression of efflux pump protein-encoding genes in an iron-responsive manner. Herein, we describe this connection and report that levels of gonococcal resistance to a substrate of the _mtrCDE_-encoded efflux pump can be modulated by MpeR and the availability of free iron. Using microarray analysis, we found that the mtrR gene, which encodes a direct repressor (MtrR) of mtrCDE, is an MpeR-repressed determinant in the late logarithmic phase of growth when free iron levels would be reduced due to bacterial consumption. This repression was enhanced under conditions of iron limitation and resulted in increased expression of the mtrCDE efflux pump operon. Furthermore, as judged by DNA-binding analysis, MpeR-mediated repression of mtrR was direct. Collectively, our results indicate that both genetic and physiologic parameters (e.g., iron availability) can influence the expression of the mtr efflux system and modulate levels of gonococcal susceptibility to efflux pump substrates.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a strict human pathogen and the causative agent of the sexually transmitted infection (STI) termed gonorrhea. Gonorrhea ranks second in the United States as the most common STI, with a rate of infection reported to be 112 cases per 100,000 people in 2008 (7). Worldwide, it has been estimated that over 90 million cases of gonorrhea occur each year (35). This annual incidence of gonorrhea, the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant clinical isolates (39), especially those expressing decreased susceptibility or clinical resistance to ceftriaxone (6, 18, 38), evidence that repeated gonococcal infections increase host susceptibility to infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (4, 25), the lack of a protective vaccine (5), and the serious consequences of infection on the reproductive health of males and females make gonorrhea a major global health problem.

With respect to antibiotic resistance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention placed N. gonorrhoeae on the “Super Bugs” list in 2007, and growing concern exists about the future of antibiotic therapy in treating gonorrhea (17, 23). Accordingly, it is important to understand the genetic and physiologic processes that govern antibiotic resistance in the gonococcus. In this respect, energy-dependent efflux of multiple, structurally diverse antimicrobials by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE (Mtr) system is an important mechanism used by gonococci to resist the bactericidal action of certain antibiotics (e.g., β-lactams and macrolides), topically applied spermicides (e.g., nonoxynol-9), and host-derived compounds that participate in innate host defense (e.g., progesterone and the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 [20, 29]). Not only does the Mtr efflux pump assist gonococci in developing clinically significant levels of antibiotic resistance, it also provides an advantage during infection since its production is required for a sustained lower genital tract infection in a female mouse model (20). Moreover, the ability of gonococci to upregulate its production provides a fitness benefit because certain _cis_- or _trans_-acting mutations that enhance mtrCDE expression can significantly increase levels of in vivo fitness in the mouse model of infection (36, 37).

Besides the mtrCDE efflux pump-encoding operon, two additional genes within the mtr locus are important in the ability of gonococci to export antimicrobials recognized by the Mtr efflux pump. The mtrR gene, which encodes a transcriptional repressor (MtrR) of mtrCDE, is closely linked to the mtrF gene, which encodes a putative inner membrane protein (MtrF); both genes are upstream of mtrCDE (15). MtrR, a member of the QacR/TetR family of DNA-binding proteins, dampens mtrCDE expression by binding within the promoter region of mtrCDE (15, 24). MtrR can also repress mtrF (12) and can positively or negatively control the expression of over 65 genes outside the mtr locus that are scattered throughout the chromosome (11). Although the precise function of MtrF in gonococci remains to be determined, it seems to function as an accessory protein for the Mtr efflux pump, needed for high levels of antimicrobial resistance mediated by the Mtr efflux pump (12, 34). In addition to being under the negative control of MtrR (11, 12), mtrF is subject to repression by MpeR, which is an AraC-like transcriptional regulator (12). The mpeR gene is restricted to pathogenic Neisseria (9) and is negatively regulated by Fur (ferric uptake regulator) and iron (19). Interestingly, MpeR has recently been found by Hollander et al. (16) to directly activate the fetA gene of N. gonorrhoeae strain FA1090; FetA is a surface-exposed receptor for enterobactin-like siderophores (2). MpeR may also be linked to iron acquisition systems in N. meningitidis, as Fantappie et al. (9) reported that it can bind near the promoter for a gene (annotated as NMB1880) that encodes a FetB-like lipoprotein thought to bind siderophores in the periplasmic space.

Given the likely importance of MpeR in determining levels of gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials and a possible connection of this regulatory protein with iron acquisition and regulatory processes, we sought to determine the number and types of genes controlled by MpeR. In this context, we now report that the expression of the gene encoding the major transcriptional repressor (MtrR) of the mtrCDE efflux pump operon is controlled by MpeR and levels of free iron.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and DH5α mcr were used in all cloning experiments. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates and incubated at 37°C. N. gonorrhoeae strain FA19 was used as the primary gonococcal strain (28), and all strains were grown on gonococcal medium base (GCB) agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) containing defined supplements I and II at 37°C under 3.8% (vol/vol) CO2 or in GCB broth with supplements I and II and sodium bicarbonate as previously described (28); except for transformation experiments, nonpiliated, transparent colonies were selected for growth. Iron-depleted cultures were grown in GCB broth containing the above-described supplements and 200 μM deferoxamine mesylate (Desferal). The plasmids and oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Biochemical (St. Louis, MO.).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype_a_ | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | ||

| FA19 | Wild type | P. F. Sparling |

| JF1 | Δ_mtrR_ in FA19 | 12 |

| JF4 | Inactivation of mtrF with insertion of aphA-3 in FA19 (Kmr) | 12 |

| JF5 | Inactivation of mpeR with insertion of aphA-3 in FA19 (Kmr) | 12 |

| FA140 | Mutation in promoter region of mtrR, missense mutation at codon 45 (Gly-45 to Asp-45) of mtrR | P. F. Sparling |

| WV16 | Inactivation of mtrF with insertion of aphA-3 in FA140 (Kmr) | 34 |

| FA19 mtrF-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrF in FA19 (Cmr) | 12 |

| JF5 mtrF-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrF in JF5 (Cmr), Kmr | 12 |

| AD1 | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrF (Cmr), mpeR+ (Eryr) in JF5 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD2 | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mpeR in FA19 (Cmr) | This study |

| FA19 mtrR-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrR in FA19 (Cmr) | 11 |

| JF5 mtrR-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrR in JF5 (Cmr), (Kmr) | This study |

| AD3 | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrR (Cmr), mpeR+ (Eryr) in JF5 (Kmr) | This study |

| FA19 mtrC-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrC in FA19 (Cmr) | 12 |

| JF1 mtrC-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrC in JF1 (Cmr) | This study |

| JF5 mtrC-lacZ | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrC in JF5 (Cmr), Kmr | 12 |

| AD4 | Chromosomal insertion of a translational fusion of lacZ to the promoter region of mtrC (Cmr), mpeR+ (Eryr) in JF5 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD5 | Chromosomal complementation of mpeR (Eryr) in strain JF5 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD6 | Inactivation of terC with insertion of aphA-3 in FA19 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD7 | Chromosomal complementation of terC (Eryr) in strain AD6 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD8 | Chromosomal complementation of mpeR (Eryr) in strain AD7 (Kmr) | This study |

| AD9 | Inactivation of mpeR with insertion of aphA-3 in FA140 (Kmr) | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F− ϕ80d_lacZ_ΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 λ−gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| TOP10 | (F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC)ϕ80 lacZ_ΔM15 Δ_lacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr_endAI nupG_) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMal-c2X | Vector for expression of protein fusions to maltose-binding protein | New England Biolabs |

| pLES94 | pUC18-derived cloning vector for fusion of gonococcal genes to a promoterless lacZ and chromosomal insertion between proA and proB (Apr) | 30 |

| pGCC3 | NICS vector for cloning mpeR and terC under the control of their own promoters and chromosomal complementation between lctP and aspC | 31 |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide used | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| 5′pMpeRpac | GGTTAATTAAGCAAACAACCTGCAGAAACC |

| 3′GC4MpeR2 | GGTTTAAACTCAGCACTTTTTCACATCCGA |

| 5′AterC | GCAACACATAGGGAGACGCTTT |

| 3′BterCSma | CATAATCATGTCCTTCCCGGGAAC |

| 5′CterCSma | GTTCCCGGGAAGGACATGATTATG |

| 3′DterC | GCTTTCGCGTATGCCCATCATAC |

| 5′pterCPac | GGTTAATTAATCTCGCCGAAGGGGAGGA |

| 3′GC4terC | GGTTTAAACTTCTTCGGGCAATTTGGTGAT |

| 5′mpeR | ATGAACACCGCCGCCATCT |

| 3′mpeR | GCACTTTTTCACACTCGAAGG |

| 5′malEmpeR-F | CACTGGGGATCCATGAATACCGCCGCCATCT |

| 3′malEmpeR-R | CACTGGCTGCAGTCAGCACTTTTTCACATCCGA |

| 5′misR−205 | CACCGCTGCTGCCCGAACTGCTC |

| 3′misR+104 | AGCAGGGCATCGTCATCTACGAG |

| 5′KH9#1 | GTCGCAGATACGTTGGAACAACG |

| 3′CEL2A | GCTTTGATACCCGAATGTTCG |

| 5′pmtrF-F | TTAATTTCCCCTATCATCGCA |

| 3′pmtrF-R | TAAATTTTTGAATTTAACATGAAG |

| 5′pmpeR | TAGGATCCGCAAACAACCTGAAGAAACC |

| 3′pmpeR | ATGGATCCCGGTTCATGATTGGATAGGAAC |

RNA isolation, microarray design, cDNA labeling and hybridization, and array analysis.

Strains FA19 and JF5 (as FA19 but mpeR::Km [12]) were grown in 50 ml of GCB broth, and samples of each strain were harvested at both the mid-log (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.6) and late log (OD600 = 0.9) phases of growth for RNA isolation using the hot-phenol method as previously described (8). Following DNase treatment (Qiagen DNase kit), RNA recovery (Qiagen RNeasy minikit), and quantification by a NanoDrop 1000 (NanoDrop Technologies), microarray analysis was performed (11). The microarray design, cDNA labeling and hybridization, and data analysis of the array were all conducted as previously described (11). Genes that showed expression differences of 1.5-fold (P ≤ 0.05) were considered to be subject to MpeR regulation. Gene numbers were designated using FA1090 genome annotation (http://www.genome.ou.edu).

Inactivation of mpeR in strain FA140 and hydrophobic agent susceptibility testing.

Chromosomal DNA from strain JF5 was used as a template to PCR amplify mpeR::Km with primers 5′mpeR and 3′mpeR (Table 2). The resulting PCR product was gel purified and used to transform piliated colony variants of strain FA140. Transformants were selected on GCB agar with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin (Km); a representative transformant (see strain AD9 in Table 1) was chosen for further study, and the presence of an inactivated mpeR gene was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequence analyses. The MICs of selected antimicrobial agents were determined as previously described (14).

Complementation of mpeR::Km.

In order to complement the mpeR::Km mutation in strain JF5 (Table 1), primers 5′pMpeRpac and 3′GC4MpeR (Table 2) were used to PCR amplify the wild-type mpeR gene and 250 bp of upstream sequence from FA19 chromosomal DNA. The resulting DNA fragment was cloned into pGCC3 (31) at the PmeI and PacI (New England BioLabs) sites to produce pGCC3-mpeR. Following DNA sequencing to confirm the correct orientation, this construct was transformed into JF5 mtrF-lacZ, JF5 mtrR-lacZ, JF5 mtrC-lacZ, and JF5 gonococcal strains (Table 1) as previously described (13). Transformants in which mpeR recombined into the chromosome between the lctP and aspC genes were selected on GCB agar containing 1 μg/ml of erythromycin (Ery), and the presence of the inserted DNA was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers 5′mpeR and 3′mpeR. The resulting strains were named AD1 (JF5 mtrF-lacZ mpeR+), AD3 (JF5 mtrR-lacZ mpeR+), AD4 (JF5 mtrC-lacZ mpeR+), and AD5 (JF5 mpeR+) (Table 1).

Construction of lacZ fusion strains in gonococci, preparation of cell extracts, and β-galactosidase assays.

All translational lacZ fusions were constructed as previously described (30). In order to construct the FA19 mpeR-lacZ strain (Table 1), the 161-bp sequence upstream of mpeR was PCR amplified from strain FA19 using primers 5′pmpeR and 3′pmpeR (Table 2) and inserted into the BamHI site of pLES94. This construct was transformed into DH5α TOP10; the correct insertion and correct orientation were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmid construct was then transformed into FA19, which allowed for insertion of the translational fusion between the proAB genes. Transformants were selected on GCB agar with 1 μg/ml of chloramphenicol (Cm). The JF5 mtrR-lacZ strain was constructed by PCR amplifying mpeR::Km from strain JF5 using primers 5′mpeR and 3′mpeR (Table 2). This DNA fragment was used to transform the FA19 mtrR-lacZ strain. Transformants were selected on GCB agar with 50 μg/ml of Km, and sequencing of a PCR-amplified product was performed to confirm disruption of mpeR. In order to construct the JF1 mtrC-lacZ strain, the promoter sequence of mtrC (15) was cloned into pLES94 as previously described (12), and this plasmid construct was transformed into JF1. Insertion and selection of transformants were performed as described for construction of the FA19 mpeR-lacZ strain. Strains harboring lacZ fusions were grown in GCB broth, and 15 ml of culture was harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the remaining pellet was washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and resuspended in lysis buffer (0.25 mM Tris [pH 8.0]). Cells were lysed, and β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (12, 32).

Inactivation of terC and complementation of the terC null mutant.

The terC gene (NGO1059) was inactivated as previously described (12, 22). Briefly, the primer sets 5′AterC and 3′BterCSma along with 5′CterCSma and 3′DterC (Table 2) were used to PCR amplify terC from FA19 chromosomal DNA in order to engineer an SmaI site within the gene. The products from these two PCRs were then used as a template to PCR amplify the entire gene using primers 5′A_terC_ and 3′D_terC_. This 1,500-bp PCR product was inserted into pBAD-TOPO-T/A and transformed into E. coli TOP10 as described in the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). The nonpolar kanamycin resistance cassette aphA-3 (26) was digested from pUC18K with SmaI and cloned into the engineered SmaI site of terC. This construct was transformed into DH5α TOP10, and following plasmid purification, the inactivated terC::Km sequence was PCR amplified using primers 5′AterC and 3′DterC. This plasmid was used to transform FA19, and transformants harboring the disrupted gene (see strain AD6 in Table 1) were selected on GCB agar containing 50 μg/ml of Km. The presence of the inactivated terC gene was confirmed by PCR and sequencing analysis. Complementation of terC in strain AD6 was done as described for mpeR (see above) except that primers 5′pterCPac and 3′GC4terC (Table 2) were used to amplify terC from FA19 chromosomal DNA. The resulting complemented strain was termed AD7 (Table 1).

Immunodetection of MtrR.

Strain FA19 was grown in GCB broth under iron-replete or -depleted conditions as described above. At the late logarithmic phase of growth, samples were harvested by centrifugation, cell extracts were solubilized, and proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Western immunoblotting was conducted as described previously (10). MtrR was detected using rabbit anti-MtrR antiserum (1:1,000) and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G coupled to alkaline phosphatase (1:1,000) as described previously (11). This analysis was conducted using three independent pairs of samples, and digital images of the immunoblots were used to quantify differences in pixel intensity for the MtrR band in lanes containing separated whole-cell lysates from strain FA19 grown under iron-replete or iron-depleted conditions. Quantification was done using the Adobe Photoshop program at fixed identical dimensions for all blots. The statistical significance of the difference in protein expression was calculated using a paired Student t test.

Construction and purification of the MBP-MpeR fusion protein.

MpeR was fused in frame at its N terminus to maltose-binding protein (MBP) by using the pMal-c2x fusion vector (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). Primers 5′malEmpeRF and 3′malEmpeRR (Table 2) were used in PCR to obtain a product for subsequent cloning as previously described (16). Growth of the E. coli transformant bearing the plasmid construct, induction of expression, and purification of MBP-MpeR were performed as previously described (21).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

The mtrR promoter region was PCR amplified from FA19 chromosomal DNA using primers 5′KH9#1 and 3′cel2A (Table 2) to generate a 360-bp product and purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The PCR product was radiolabeled and purified as previously described (16). The labeled DNA fragment (10 ng) was incubated with 15 μg of fusion protein (MBP-MpeR). Specificity of binding was shown by incubating 15 μg of MBP-MpeR and 10 ng of the radiolabeled mtrR probe with increasing concentrations of a 360-bp cold specific competitor (nonradiolabeled mtrR) or increasing concentrations of a 309-bp cold nonspecific competitor (nonradiolabeled misR); the latter was PCR amplified using 5′misR−205 and 3′misR+104 (Table 2). All reaction mixtures were incubated along with DNA-binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μg/ml of poly(dI-dC)] for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 5% (wt/vol) native polyacrylamide gel at 4°C followed by autoradiography.

Primer extension of mtrF.

In order to determine the start site for mtrF transcription, total RNA was prepared from a mid-logarithmic culture of strain FA19 as described above. The primer 3′mtrF-R was radiolabeled using [γ-32P] and T4 polynucleotide kinase and used to reverse transcribe 10 μg of total RNA. The primers 5′pmtrF-F and 3′pmtrF-R (Table 2) were used along with FA19 chromosomal DNA as a template to amplify the mtrF promoter region in order to generate reference sequence products using a SequiTherm Excel II DNA sequencing kit (Epicentre). Both the primer extension product and the reference sequence were subjected to electrophoresis on a 6% (wt/vol) sequencing gel that was dried. Autoradiography was performed for visualization of the primer extension product.

Statistical analysis.

Except where indicated, statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed, paired Student t test. P values for specific comparisons are listed in the figure legends.

Microarray data expression number.

Gene expression data for all microarray experiments can be retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE32717.

RESULTS

MpeR regulation of mtrF and influence of iron availability.

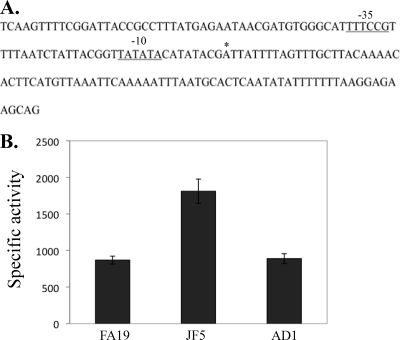

Prior to determining the MpeR regulon in N. gonorrhoeae strain FA19 (see below), we confirmed that mtrF expression is negatively controlled by MpeR (12) and that such regulation is influenced by iron availability, as suggested by previous studies (8, 19). For this purpose, we constructed a complemented derivative (strain AD1) of strain JF5 (as FA19 but mpeR::Km) (Table 1), which expressed mpeR ectopically from its own promoter when placed between the lctP and aspC genes (31). In order to monitor mtrF expression, we used a previously described (12) mtrF::lacZ translational fusion that harbors 161 bp of the DNA sequence upstream of mtrF (Fig. 1A) containing the promoter element for mtrF transcription. This promoter was assigned as such based on results from primer extension analysis that showed a transcriptional start point (data not shown) 9 nucleotides downstream of a near-consensus −10 hexamer sequence (Fig. 1A). This putative −10 element was separated from a potential −35 hexamer sequence by an optimal 17 nucleotides. When the mtrF-lacZ fusion was introduced into strains FA19, JF5, and AD1, we found that the expression of mtrF-lacZ was significantly higher in the mpeR::Km mutant (JF5) than in either the wild-type or complemented strain (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Regulation of mtrF by MpeR. (A) DNA sequence of a 161-bp fragment used in mtrF-lacZ expression analysis, with an asterisk marking the start of transcription. (B) The specific activities (nanomoles of _o_-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per mg of protein) for measuring mtrF-lacZ expression in the FA19 mtrF-lacZ, JF5 mtrF-lacZ, and AD1 (JF5 mtrF-lacZ mpeR+ [Table 1]) strains are shown. Samples were harvested from gonococci to the mid-log phase of growth. The above-described experiment was done in triplicate and is a representative example of three independent experiments. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The difference in expression of mtrF-lacZ between FA19 and JF5 was significant (P = 0.001), as was the difference in expression of mtrF-lacZ between JF5 and AD1 (P = 0.001).

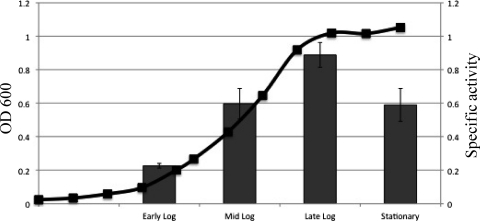

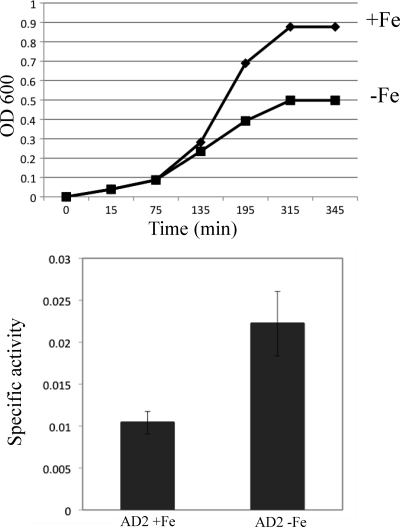

We next tested whether conditions of iron depletion would have an impact on mpeR expression in strain FA19 as previously reported by Ducey et al. (8) and later found by Jackson et al. (19) to involve a Fur-dependent mechanism. As is shown in Fig. 2, the peak of mpeR expression in strain AD2 (as FA19 but mpeR-lacZ) grown in iron-replete GCB broth occurred at the late logarithmic phase of growth when free iron levels would be reduced due to consumption. Based on this result, we next monitored mpeR-lacZ expression during growth of strain AD2 under iron-replete and iron-depleted (with deferoxamine mesylate) conditions and harvested cells at the late log phase of growth. As expected, the culture growing under iron-depleted conditions had a severe growth defect compared to the control culture, yet expressed mpeR at higher levels (Fig. 3). This result was consistent with the conclusions reached by Ducey et al. (8) and Jackson et al. (19) that mpeR is an iron-repressed gene in gonococci.

Fig 2.

Maximal expression of mpeR. The specific activities (nanomoles of _o_-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside hydrolyzed per mg of protein) for measuring mpeR-lacZ expression in strain AD2 (FA19 mpeR-lacZ [Table 1]) at different phases of growth under iron-replete conditions are shown. The above-described experiment was done in triplicate and is a representative example of three independent experiments. Error bars represent one standard deviation, and differences in expression of mpeR-lacZ at the early log, mid-log, late log, and stationary phases of growth were significant (P < 0.05).

Fig 3.

Expression of mpeR under iron-replete and -depleted conditions. The growth of strain AD2 (FA19 mpeR-lacZ [Table 1]) under either iron-replete (+Fe) or iron-depleted (−Fe) conditions (top panel) and the expression of mpeR-lacZ (bottom panel) are shown. Samples from the growth curve were harvested from gonococci at the late log phase of growth. The experiment was done in triplicate and is a representative example of three independent experiments. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The difference in expression of mpeR-lacZ between cultures grown under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions was significant (P = 0.007).

Antimicrobial susceptibility of gonococci can be modulated by MpeR and iron availability.

In order to determine whether production of MpeR, which negatively regulates the expression of mtrF (12), can influence levels of gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials recognized by the Mtr efflux pump system in an iron-dependent manner, we assessed the susceptibility of strain FA140 to Triton X-100, a known substrate of the pump when grown under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions. We used FA140 for this purpose because loss of mtrF in this strain, but not in wild-type strain FA19, has a phenotype (e.g., hypersusceptibility to Triton X-100 [34]). Interestingly, Triton X-100 is structurally similar to the over-the-counter spermicide nonoxynol-9, which also displays antigonococcal action (12, 34). FA140 expresses a high level of resistance to Triton X-100 mediated by the Mtr efflux pump due to a single base pair deletion in the mtrR promoter that abrogates mtrR expression, resulting in elevated expression of mtrCDE (33). With FA140, we found that Triton X-100 resistance was substantially higher (>64-fold) in the iron-replete culture than in the iron-depleted culture (Table 3). In order to determine whether this iron-dependent Triton X-100 resistance required mpeR and/or mtrF, we next examined genetic derivatives of FA140 that contained inactivated copies of these genes. Using strain WV16 (as FA140 but _mtrF::_Km), we confirmed that the loss of mtrF significantly enhances gonococcal susceptibility to Triton X-100 (Table 3). Importantly, there was no difference between the Triton X-100 MIC values for the cultures grown under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions. In contrast to parent strain FA140, strain AD9 (as FA140 _mpeR::_Km) expressed a high level of Triton X-100 resistance independent of iron availability (Table 3), indicating that the iron-dependent phenotype of antimicrobial susceptibility requires MpeR.

Table 3.

Effect of iron and mpeR on high-level Triton X-100 resistance due to mtrR mutations

| Strain | MIC (μg of Triton X-100/ml)a |

|---|---|

| FA140 +Fe | >16,000 |

| FA140 −Fe | 375 |

| WV16 +Fe | 125 |

| WV16 −Fe | 125 |

| AD9 +Fe | >16,000 |

| AD9 −Fe | >16,000 |

Identification of MpeR-regulated genes associated with antimicrobial resistance.

In order to identify MpeR-regulated genes besides mtrF that are involved in antimicrobial resistance, we used RNA from strains FA19 and JF5 to identify the MpeR regulon in wild-type strain FA19. As is shown in Tables 4 and 5, microarray analysis of RNA pairs prepared from mid-logarithmic and late logarithmic phase cultures of these strains revealed a total of 67 MpeR-regulated genes, with 46 being MpeR repressed (30 at mid-log and 16 at late log) and 21 activated in the presence of MpeR (16 at mid-log and 5 at late log). The finding that mtrF expression was elevated in strain JF5 is consistent with earlier work (12) (Fig. 1B) that mtrF is an MpeR-repressed gene (Table 4), and it served as an internal control that validated our use of the microarray system to detect MpeR-regulated genes. Interestingly, for both MpeR-repressed and -activated genes, there was no overlap of regulated genes in the mid-log and late log RNA samples.

Table 4.

MpeR-regulated genes at mid-log phase in Neisseria gonorrhoeae

| Gene_a_ | Common name | Fold change | Functional classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| MpeR repressed | |||

| NGO0018 | NGO0018 | 1.53 | Unknown |

| NGO0205 | lolA | 1.60 | Putative outer membrane lipoprotein carrier protein |

| NGO0373 | NGO0373 | 1.75 | Putative ABC transporter permease |

| NGO0393 | NGO0393 | 1.52 | Putative TetR family transcriptional regulator |

| NGO0678 | NGO0678 | 1.59 | Unknown |

| NGO0679 | leuC | 1.51 | Isopropylmalate isomerase large subunit |

| NGO0754 | mobA | 1.56 | Putative molybdoprotein guanine dinucleotide biosynthesis protein |

| NGO0795 | bfrB | 2.24 | Bacterioferritin B |

| NGO0863 | NGO0863 | 1.69 | Putative oxidoreductase |

| NGO0891 | NGO0891 | 1.95 | Unknown |

| NGO0916 | sucB | 1.65 | Dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase |

| NGO1046 | clpB | 1.66 | Putative ClpB protein |

| NGO1273 | NGO1273 | 1.51 | Unknown |

| NGO1368 | mtrF | 2.22 | Mtr efflux pump protein component |

| NGO1416 | nqrD | 1.80 | NADH-ubiquinone reductase |

| NGO1418 | nqrF | 1.70 | Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase subunit F |

| NGO1422 | grpE | 1.71 | Putative heat shock protein |

| NGO1428 | NGO1428 | 1.53 | Unknown |

| NGO1494 | potF | 1.71 | Spermidine/putrescine ABC transporter |

| NGO1600 | glnA | 1.95 | Glutamine synthetase |

| NGO1665 | ilvE | 1.62 | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase |

| NGO1685 | NGO1685 | 1.68 | Unknown |

| NGO1749 | nuoC | 1.52 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit C |

| NGO1765 | pglA | 1.51 | Putative glycosyltransferase |

| NGO1770 | prlC | 1.54 | Oligopeptidase A |

| NGO1780 | NGO1780 | 1.67 | Unknown |

| NGO1809 | valS | 1.50 | Valyl-tRNA synthetase |

| NGO2013 | glnQ | 1.82 | Putative ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| NGO2014 | cjaA | 2.15 | Putative ABC transporter, periplasmic binding protein |

| NGO2094 | groES | 1.84 | Cochaperonin GroES |

| MpeR activated | |||

| NGO0221 | NGO0221 | 1.57 | Putative deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphatase |

| NG00527 | NGO0527 | 1.58 | Unknown |

| NGO0567 | NGO0567 | 1.69 | Putative hydrolase |

| NGO0606 | NGO0606 | 1.58 | Putative sodium-dependent transport Protein |

| NGO0694 | NGO0694 | 1.62 | Unknown |

| NGO0820 | mesJ | 1.75 | Putative cell cycle protein |

| NGO0876 | NGO0876 | 1.90 | Unknown |

| NGO0958 | rph | 1.62 | Putative RNase PH |

| NGO1058 | surE | 1.64 | Stationary-phase survival protein |

| NGO1059 | NGO1059 | 2.17 | Putative tellurium resistance gene |

| NGO1079 | NGO1079 | 1.69 | Putative oxidoreductase |

| NGO1406 | gcvT | 1.55 | Aminomethyltransferase |

| NGO1488 | NGO1488 | 1.53 | Unknown |

| NGO1810 | NGO1810 | 1.62 | Unknown |

| NGO2132 | NGO2132 | 1.58 | Unknown |

| NGO2167 | NGO2167 | 1.51 | Unknown |

Table 5.

MpeR-regulated genes at late log phase in Neisseria gonorrhoeae

| Gene_a_ | Common name | Fold change | Functional classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| MpeR repressed | |||

| NGO0365 | dcmG | 1.94 | Site-specific DNA methyltransferase |

| NGO0672 | NGO0672 | 1.98 | Unknown |

| NGO0924 | NGO0924 | 1.51 | Unknown |

| NGO0952 | NGO0952 | 1.51 | Putative TonB-dependent receptor protein |

| NGO1107 | NGO1107 | 1.62 | Unknown |

| NGO1159 | NGO1159 | 1.59 | Unknown |

| NGO1176 | NGO1176 | 1.88 | Unknown |

| NGO1313 | NGO1313 | 1.76 | Unknown |

| NGO1342 | dhpS | 1.67 | Dihydropteroate synthase |

| NGO1366 | mtrR | 1.74 | mtrCDE transcriptional regulator, repressor |

| NGO1481 | bioC | 1.52 | Biotin synthesis protein |

| NGO1771 | NGO1771 | 1.63 | Unknown |

| NGO1847 | NGO1847 | 1.65 | Unknown |

| NGO1915 | kdtA | 1.81 | 3-Deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic-acid transferase |

| NGO1951 | prfB | 2.40 | Peptide chain release factor 2 |

| NGO2042 | pilS | 1.87 | Pilin silent gene cassette |

| MpeR activated | |||

| NGO1151 | NGO1151 | 1.63 | Unknown |

| NGO1170 | NGO1170 | 1.95 | Unknown |

| NGO1179 | NGO1179 | 1.97 | Unknown |

| NGO1270 | NGO1270 | 1.95 | Unknown |

| NGO1498 | NGO1498 | 1.58 | Unknown |

With respect to genes known or possibly involved in antimicrobial resistance, we identified, in addition to mtrF, two genes of interest: mtrR and terC. The expression of mtrR, which encodes the major transcriptional repressor (MtrR) of the mtrCDE operon (15) and can also negatively control mtrF independently of MpeR (12), was identified as an MpeR-repressed gene (1.74-fold change) in the late log culture of strain FA19. In contrast, terC (NGO1059), which has been provisionally annotated (http://www.genome.ou.edu) as encoding a putative membrane protein (TerC) involved in tellurium resistance (3), was found to be MpeR activated (2.17-fold change) but only in the mid-log phase of growth. While much is known about mtrR (10, 11, 15, 21, 24, 27, 36), little information is available about terC in gonococci. The gene terC is of interest, however, because it contains a polynucleotide repeat (A-8) in its coding sequence, making it a candidate for being a phase-variable gene. Since analysis of the FA1090 genome sequence (http://www.genome.ou.edu) and our own sequencing of the terC gene in FA19 (data not shown) showed that terC would be in the “phase-on” sequence in these strains, we asked whether it was involved in resistance to tellurium as well as antimicrobials recognized by the Mtr efflux pump. For this purpose, a null mutation in terC was constructed in strain FA19 (see Materials and Methods); this mutant strain was named AD6. Strain AD6 was then complemented with the wild-type terC gene from FA19, which was cloned into pGCC3 and expressed from its own promoter between lctP and aspC genes in the chromosome; this complemented strain was termed AD7. Using these strains, we found that the loss of terC increased gonococcal susceptibility to potassium tellurite (Table 6) but not other tested antimicrobials (e.g., silver nitrate and Triton X-100), including one (Triton X-100) recognized by the Mtr efflux pump; this change in tellurium susceptibility endowed by the null mutation could be reversed by complementation. Consistent with terC being an MpeR-activated gene, the loss of mpeR in strain JF5 also resulted in hypersusceptibility of gonococci to potassium tellurite, but this was reversed by complementation when a wild-type copy of mpeR was expressed ectopically (see strain AD5 in Table 6). Since the terC mutant did not show hypersusceptibility to a substrate of the Mtr efflux pump (e.g., Triton X-100), we concentrated on MpeR control of mtrR and a target of MtrR regulation (mtrCDE).

Table 6.

Effect of terC and mpeR on the susceptibility of gonococci to potassium tellurite

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K2TeO3 | AgNO3 | Triton X-100 | |

| FA19 | 1.0 | 20 | 100 |

| AD6 | 0.05 | 20 | 100 |

| AD7 | 0.5 | 20 | 100 |

| JF5 | 0.05 | 20 | 100 |

| AD5 | 1 | 20 | 100 |

MpeR regulation of mtrR and mtrCDE.

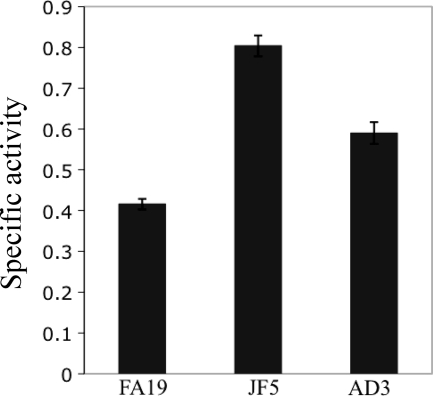

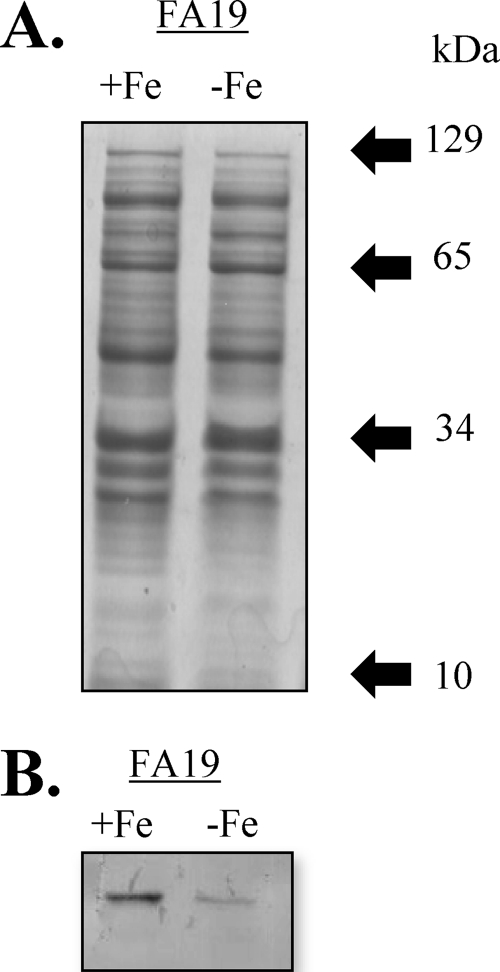

The observation that mtrR expression was repressed by MpeR in the late log phase culture of strain FA19 (Table 5) suggested that MpeR could indirectly regulate the mtrCDE efflux pump operon through modulation of MtrR levels and that such regulation could be iron dependent. To test this hypothesis, we examined mtrR and mtrC expression in MpeR-positive and MpeR-negative strains grown under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions. Using the FA19 mtrR-lacZ and JF5 mtrR-lacZ strains and the _mpeR_-complemented strain with the mtrR-lacZ fusion (AD3), we found that mtrR expression was decreased in the MpeR-positive strains compared to that in the MpeR-negative strain JF5, confirming that it is an MpeR-repressible gene (Fig. 4). Based on this result, we next tested whether levels of MtrR would differ in wild-type strain FA19 grown under iron-replete and iron-depleted conditions. Using SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates that employed anti-MtrR antiserum, we found that the level of MtrR in strain FA19 was increased by 42% (P = 0.03) when grown under iron-replete conditions compared to that under iron-depleted conditions (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Regulation of mtrR by MpeR. mtrR expression in the FA19 mtrR-lacZ, JF5 mtrR-lacZ, and AD3 (JF5 mtrR-lacZ mpeR+ [Table 1]) strains as determined by translational lacZ fusions. Samples were harvested from gonococci at the late log phase of growth. The above-described experiment was done in triplicate and is a representative example of three independent experiments. Error bars represent one standard deviation. The difference in expression of mtrR-lacZ between FA19 and JF5 was significant (P ≤ 0.001), as was the difference in mtrR-lacZ expression between JF5 and AD3 (P ≤ 0.001).

Fig 5.

Iron modulates levels of MtrR. Wild-type strain FA19 was grown under iron-replete and -depleted conditions. (A) Samples for each growth condition were harvested at the late log phase of growth, solubilized, and separated by SDS-PAGE; the electrophoretic mobility of each molecular mass marker is shown by the arrow. (B) Following transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was probed with anti-MtrR antiserum and the difference in MtrR levels was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

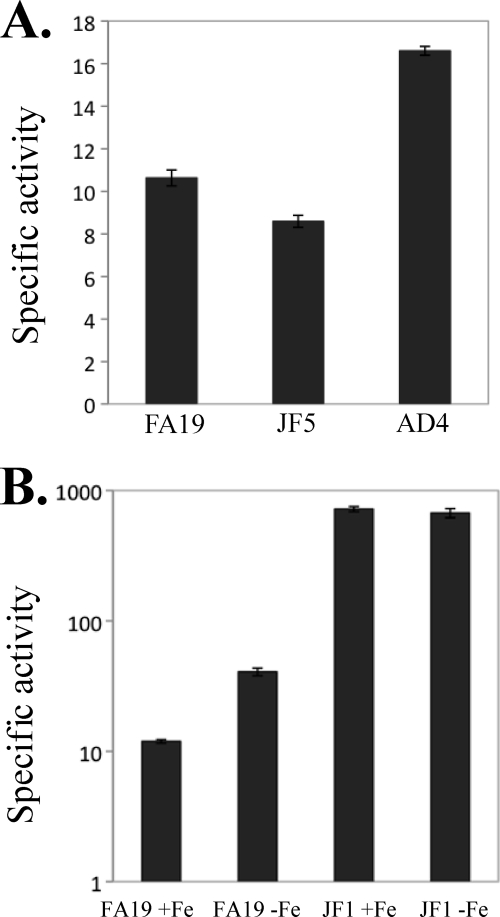

Our finding that levels of MtrR in gonococci can change due to the presence of MpeR and levels of iron suggested that MtrR control of the mtrCDE efflux pump operon is regulated by MpeR and iron availability. As a further test of this model, we monitored the expression of an mtrC-lacZ fusion in FA19, JF5, and the mpeR_-complemented strain termed AD4 (Table 1). We found that the loss of mpeR in strain JF5 decreased mtrC-lacZ expression by nearly 20% (P = 0.002), which was reversed by complementation when the wild-type mpeR gene was expressed ectopically in strain AD4 (Fig. 6A); this small but significant difference in mtrC-lacZ expression may explain why the mtrCDE genes were not identified in the microarray studies as being MpeR regulated. Additionally, we observed that iron-depleted conditions (with deferoxamine mesylate) enhanced mtrC-lacZ expression in strain FA19 (Fig. 6B). Since MtrR is a direct repressor of mtrCDE (15, 24) and its expression can be controlled by levels of iron and MpeR, we hypothesized that the expression of mtrC-lacZ would not be affected by the availability of iron in an MtrR-negative strain. In order to test this possibility, we used strains FA19 and JF1 (as FA19 but Δ_mtrR) containing an mtrC-lacZ translational fusion. We found that although the level of mtrC-lacZ expression was higher in the JF1 background, unlike that of strain FA19, it was not influenced by iron limitation (Fig. 6B).

Fig 6.

Regulation of mtrCDE expression is modulated by mpeR expression and levels of free iron but not mtrR expression. (A) mtrCDE expression levels in the FA19 mtrC-lacZ, JF5 mtrC-lacZ, and AD4 (JF5 mtrC-lacZ mpeR+ [Table 1]) strains were measured. The difference in mtrCDE expression between strains FA19 and JF5 was significant (P = 0.002), as was that between strains JF5 and AD4 (P = 0.0001). (B) mtrCDE expression levels in the FA19 mtrC-lacZ and JF1 mtrC-lacZ (Table 1) strains grown under either iron-replete or iron-depleted conditions were determined. The difference in mtrCDE expression between FA19 +Fe and FA19 −Fe was significant (P = 0.0023), while that between JF1 +Fe and JF1 −Fe was not significant (P = 0.3132). The above-described experiments were done in triplicate and are representative examples of three independent experiments. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

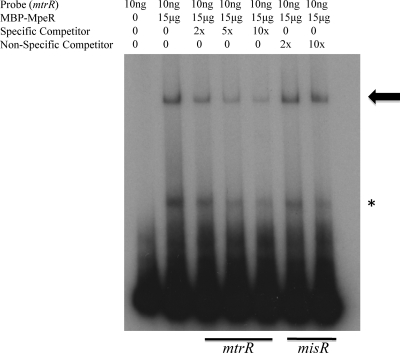

Binding of MpeR upstream of mtrR.

In order to determine whether MpeR-mediated repression of mtrR was direct, we used EMSA to detect specific binding of an MBP-MpeR fusion protein to a target 360-bp DNA sequence that contained 186 bp of the upstream region containing the mtrR promoter (14, 15) and part (174 bp) of the mtrR coding sequence. Using a competitive EMSA, we found that incubation of the target DNA with 15 μg of the MBP-MpeR fusion protein resulted in the appearance of two shifted complexes. Of these two complexes, only the slower-migrating species (shown by the arrow in Fig. 7) gave evidence of being a specific complex, as it was reduced in intensity by the presence of a specific, unlabeled probe of similar length but not a nonspecific probe (misR).

Fig 7.

MpeR binds specifically to the upstream region of mtrR. The 363-bp mtrR upstream region was radiolabeled, and 10 ng of this DNA was incubated with 15 μg of MBP-MpeR alone. In order to demonstrate that binding of MBP-MpeR to mtrR was specific, increasing concentrations (2×, 5×, and 10×) of cold specific competitor (mtrR) or increasing concentrations (2× and 10×) of cold nonspecific competitor (misR) were added. The arrow indicates the specific complex, while the asterisk indicates the nonspecific complex.

DISCUSSION

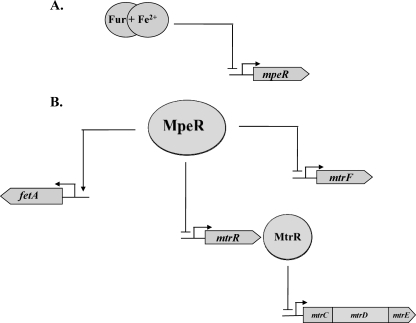

Based on the data presented herein, we propose the existence of a regulatory pathway in gonococci that controls the expression of the mtr efflux pump locus. In this model (Fig. 8), the expression of mtrF is repressed by MpeR in an iron-responsive process shown by others to involve Fur- plus iron-mediated repression of mpeR (8, 19). We propose that MpeR also indirectly enhances mtrCDE expression due to its ability to directly repress mtrR, which encodes the main repressor of this operon (27), especially when free iron levels are decreased. Taken together, we suggest that since MtrR is the direct repressor of mtrCDE (15), levels of free iron would modulate the expression of this operon by controlling levels of MpeR and in turn MtrR. We cannot presently rule out, however, that MpeR binding to the mtrR-mtrCDE intervening sequence might additionally activate mtrCDE expression directly, and additional DNA-binding studies are required to resolve this issue. The regulation of mtrF is also complex in that it is negatively controlled by both MpeR and MtrR. The mechanism(s) by which these two transcriptional regulators function together or in opposition under iron-replete or -depleted conditions is not yet clear and is the subject of ongoing investigation.

Fig 8.

Model demonstrating the regulatory properties of MpeR that affect the high-level resistance mediated by the MtrCDE efflux system in an iron-dependent manner. (A) Under iron-replete conditions, Fur complexed with iron represses the expression of mpeR. (B) Under iron-depleted conditions, mpeR is derepressed and acts to repress the expression levels of both mtrF and mtrR in strain FA19. In strain FA1090, MpeR activates the expression of fetA (16). For all genes, the bent arrows identify promoter elements, while straight arrows indicate MpeR-activated genes and blocked lines designate MpeR-repressed genes.

How might our observations help in understanding the biology and antimicrobial resistance potential of the gonococcus during infection on the genital mucosal surface, especially when this human pathogen is confronted with antimicrobials recognized by the Mtr efflux pump? For instance, in an infection where the gonococcus is confronted with an iron-restricted environment, the negative influence of Fur on mpeR expression would be diminished. We hypothesize that iron restriction would increase mpeR expression and that the increased level of MpeR would then dampen transcription of mtrR. As a consequence, levels of the Mtr efflux pump would increase, and this would enhance gonococcal infectivity as well as decrease bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials recognized by the pump. In contrast to the iron-restricted situation, women infected with gonococci can develop serious complications and often present with pelvic inflammatory disease within days of menses onset when iron levels would be elevated due to blood flow. In this scenario, mpeR expression would be reduced because the repressive action of Fur would be favored and levels of MtrR would be higher than in an iron-restricted environment. Consequently, mtrCDE expression and antimicrobial resistance mediated by the pump would be lowered. We do not yet know whether conditions of iron restriction are responsible for the remarkable differences in the number and types of genes that were observed by microarray analysis to be regulated by MpeR during the mid- and late logarithmic phases of growth (Tables 4 and 5). Despite this uncertainty, our data emphasize that transcriptional regulators such as MpeR can exhibit very different regulons depending on growth phase. Therefore, transcriptional profiling studies, particularly those involving investigations on antimicrobial resistance, should take this into account.

In addition to its importance in regulating _mtr_-associated efflux genes in gonococci, MpeR has recently been found by Hollander et al. (16) to directly activate transcription of fetA in strain FA1090 under iron-replete conditions. It is important to note that strain FA1090 employed by Hollander et al. is unrelated to strain FA19 employed in this investigation, and differences in how mpeR expression is regulated in these two strains may account for why we did not detect fetA as an MpeR-regulated gene in our array studies. Despite this uncertainty, FetA is of interest as it is the outer membrane transporter of a TonB-dependent receptor complex employed by gonococci to obtain iron bound to enterobactin-like siderophores produced by other bacteria (2, 16). FetA is also produced in Neisseria meningitidis (2) and is immunogenic, as evidenced by the presence of anti-FetA antibodies in convalescent-phase serum from patients recovering from meningococcal disease; these antibodies also cross-react with gonococci (1).

In conclusion, although MpeR was first identified based on its ability to control levels of gonococcal resistance to antimicrobials (12), it may have even greater significance in controlling genes of pathogenic Neisseria that encode proteins involved in iron utilization and perhaps other systems that are important in virulence expressed by gonococci and meningococci.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Ohneck and Y. Zalucki for critical reading of the manuscript prior to submission, J. Balthazar and V. Dhulipala for expert technical assistance, and L. Pucko for help in manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grants R37 AI021150 and U19 AI031496 (W.M.S.) and RR016478 (D.W.D.) and a VA Merit Award from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (W.M.S). W.M.S. is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist award from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Black JR, Dyer DW, Thompson MK, Sparling PF. 1986. Human immune response to iron-repressible outer membrane proteins of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect. Immun. 54:710–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson SD, Klebba PE, Newton SM, Sparling PF. 1999. Ferric enterobactin binding and utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 181:2895–2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chasteen TG, Fuentes DE, Tantalean JC, Vasquez CC. 2009. Tellurite: history, oxidative stress, and molecular mechanisms of resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:820–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, et al. 1997. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet 349:1868–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelissen CN, Hollander A. 2011. TonB-dependent transporters expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front. Microbiol. 2:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deguchi T, et al. 2003. Treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis by double-dosing of 200 mg cefixime at a 6-h interval. J. Infect. Chemother. 9:35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionne-Odom J, Tambe P, Yee E, Weinstock H, Del Rio C. 2011. Antimicrobial resistant gonorrhea in Atlanta: 1988–2006. Sex. Transm. Dis. 38:780–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducey TF, Carson MB, Orvis J, Stintzi AP, Dyer DW. 2005. Identification of the iron-responsive genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by microarray analysis in defined medium. J. Bacteriol. 187:4865–4874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fantappie L, Scarlato V, Delany I. 2011. Identification of the in vitro target of an iron-responsive AraC-like protein from Neisseria meningitidis that is in a regulatory cascade with Fur. Microbiology 157:2235–2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folster JP, Dhulipala V, Nicholas RA, Shafer WM. 2007. Differential regulation of ponA and pilMNOPQ expression by the MtrR transcriptional regulatory protein in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 189:4569–4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folster JP, et al. 2009. MtrR modulates rpoH expression and levels of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 191:287–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folster JP, Shafer WM. 2005. Regulation of mtrF expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and its role in high-level antimicrobial resistance. J. Bacteriol. 187:3713–3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunn JS, Stein DC. 1996. Use of a non-selective transformation technique to construct a multiply restriction/modification-deficient mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251:509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagman KE, et al. 1995. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antimicrobial hydrophobic agents is modulated by the mtrRCDE efflux system. Microbiology 141(Pt 3):611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagman KE, Shafer WM. 1995. Transcriptional control of the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 177:4162–4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollander A, Mercante AD, Shafer WM, Cornelissen CN. 2011. The iron-repressed, AraC-like regulator MpeR activates expression of fetA in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 79:4764–4776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ison CA, Dillon JA, Tapsall JW. 1998. The epidemiology of global antibiotic resistance among Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Haemophilus ducreyi. Lancet 351(Suppl 3):8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito M, et al. 2004. Remarkable increase in central Japan in 2001-2002 of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with decreased susceptibility to penicillin, tetracycline, oral cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3185–3187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson LA, et al. 2010. Transcriptional and functional analysis of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae Fur regulon. J. Bacteriol. 192:77–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jerse AE, et al. 2003. A gonococcal efflux pump system enhances bacterial survival in a female mouse model of genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 71:5576–5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee EH, Rouquette-Loughlin C, Folster JP, Shafer WM. 2003. FarR regulates the _farAB_-encoded efflux pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae via an MtrR regulatory mechanism. J. Bacteriol. 185:7145–7152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EH, Shafer WM. 1999. The _farAB_-encoded efflux pump mediates resistance of gonococci to long-chained antibacterial fatty acids. Mol. Microbiol. 33:839–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis DA. 2010. The gonococcus fights back: is this time a knock out? Sex. Transm. Infect. 86:415–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas CE, Balthazar JT, Hagman KE, Shafer WM. 1997. The MtrR repressor binds the DNA sequence between the mtrR and mtrC genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 179:4123–4128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClelland RS, et al. 2001. Treatment of cervicitis is associated with decreased cervical shedding of HIV-1. AIDS 15:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menard R, Sansonetti PJ, Parsot C. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899–5906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan W, Spratt BG. 1994. Regulation of the permeability of the gonococcal cell envelope by the mtr system. Mol. Microbiol. 11:769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shafer WM, Guymon LF, Lind I, Sparling PF. 1984. Identification of an envelope mutation (env-10) resulting in increased antibiotic susceptibility and pyocin resistance in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 25:767–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafer WM, Qu X, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. 1998. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1829–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver LE, Clark VL. 1995. Construction of a translational lacZ fusion system to study gene regulation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gene 166:101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skaar EP, et al. 2005. Analysis of the Piv recombinase-related gene family of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 187:1276–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder LA, Shafer WM, Saunders NJ. 2003. Divergence and transcriptional analysis of the division cell wall (dcw) gene cluster in Neisseria spp. Mol. Microbiol. 47:431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparling PF, Sarubbi FA, Jr, Blackman E. 1975. Inheritance of low-level resistance to penicillin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 124:740–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veal WL, Shafer WM. 2003. Identification of a cell envelope protein (MtrF) involved in hydrophobic antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velicko I, Unemo M. 2009. Increase in reported gonorrhoea cases in Sweden, 2001–2008. Euro Surveill. 14:19315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner DM, Folster JP, Shafer WM, Jerse AE. 2007. Regulation of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux-pump system modulates the in vivo fitness of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1804–1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner DM, Shafer WM, Jerse AE. 2008. Clinically relevant mutations that cause derepression of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump system confer different levels of antimicrobial resistance and in vivo fitness. Mol. Microbiol. 70:462–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Workowski KA, Berman SM. 2006. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recommend. Rep. 55:1–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Workowski KA, Berman SM, Douglas JM., Jr 2008. Emerging antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: urgent need to strengthen prevention strategies. Ann. Intern. Med. 148:606–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]