Family Relationships and Parental Monitoring During Middle School as Predictors of Early Adolescent Problem Behavior (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Mar 16.

Published in final edited form as: J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2012 Mar;41(2):202–213. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651989

Abstract

The middle school years are a period of increased risk for youths' engagement in antisocial behaviors, substance use, and affiliation with deviant peers (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). This study examined the specific role of parental monitoring and of family relationships (mother, father, and sibling) that are all critical to the deterrence of problem behavior in early adolescence. The study sample comprised 179 ethnically diverse 6th grade (46% female) students who were followed through 8th grade. Results indicated that parental monitoring and father–youth connectedness were associated with reductions in problem behavior over time, and conflict with siblings was linked with increases in problem behaviors. No associations were found for mother–youth connectedness. These findings did not differ for boys and for girls, or for families with resident or nonresident fathers.

Considerable attention has been devoted to understanding the developmental processes that escalate youths' antisocial behaviors and substance use, because of the strong implications these problems have for adolescent health and their impact on society at large (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). The middle school years are a particularly risky period during which the convergence of antisocial behaviors, experimentation with substances, and affiliation with deviant peers may culminate and rapidly develop into firmly rooted problems. Parenting processes and relationships among family members are also changing during this time. Youths tend to spend less time with their families, feel less close to them, and receive less supervision and monitoring from their parents (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1984; Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2003; Hill, Bromell, Tyson, & Flint, 2007). Although this is a developmentally normative shift, it is critical that youths remain connected with their families to receive guidance and support as they negotiate difficult social, emotional, and cognitive challenges during this period of life (Hill et al., 2007).

In an effort to better understand these developmental processes, our research and that of others has focused on the significant relationships in youths' lives. Among the general themes of existing literature on adolescence is that significant relationships with caregivers, peers, and siblings either serve to protect them from engaging in problem behavior or disrupt development and lead to later problems such as substance use and deviant peer affiliation. Studies have shown that family relationships that are supportive and close reduce the risk of youth substance use and problem behavior (Padilla-Walker, Nelson, Madsen, & Barry, 2008), and family management skills applied during this period can either impede or exacerbate adolescent problem behavior. Other studies have revealed that relationships with deviant peers and siblings are linked with increases in substance use, including both alcohol and drug use (Dishion & Owen, 2002; Stormshak, Comeau, & Shepard, 2004). However, few studies have examined parenting skills and the quality of early adolescents' relationships as predictors of problem behavior in the same model. This study focused on the quality of parenting skills and of family relationships as predictors of youth problem behaviors during the transition to adolescence.

Youth problem behaviors follow a developmental course, and by middle childhood, antisocial behaviors commonly include nonadherence to social or family norms and are often characterized by rule-breaking behaviors, disobedience or defiance, aggression or violence, and lying, stealing, and property destruction (Hiatt & Dishion, 2007). Unaddressed, these behaviors become more severe into adolescence and broaden to include substance use, risky sexual behavior, and delinquency (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). This trajectory makes the middle school years a particularly risky transitional period. For the most part, each of these risky or problem behaviors occurs in a peer context. For example, youths who spend time with delinquent peers are at greater risk for engaging in substance use (e.g., Crawford & Novak, 2008) and antisocial behavior (Stoolmiller, 1994). Substance use and antisocial behavior are rarely solitary activities during this period, further exemplifying the influence of peer groups on individuals' behavior (Heinze, Toro, & Urberg, 2004). In the long run, problem behaviors during early adolescence have serious implications for successful development into adulthood and come at a great personal and societal cost, including criminal or violent behavior, arrests, and substance abuse, to name a few.

Examining the context of parenting practices and relationships within the family is central to understanding why some youths become involved in the peer context of problem behaviors (e.g., Dishion & Patterson, 2006; Dishion & Stormshak, 2007; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003). During adolescence, family contexts characterized by supervision, guidance, and connectedness facilitate a successful transition into a positive peer context. However, when youths are too quickly given excessive freedom and unsupervised time, a process called premature autonomy, they are at significant risk for poor outcomes (e.g., Dishion et al., 2003; Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004). Under these circumstances, adolescents fail to benefit from parental guidance and support and consequently seek advice from peers who are inadequate surrogates (Ackard, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Perry, 2006). As such, it is critical to define what constitutes not only effective parenting that provides structure and guidance for youths, but also positive family relationships that promote closeness and connectedness with the family or negative family relationships that propel youths out of the home and into the peer context.

Parenting Practices and Family Relationships

Effective parenting practices play a critical role in preventing and reducing youth problem behaviors. In particular, parents who stay informed about their child's activities, attend to their child's behavior, and structure their child's environment have children with better outcomes (Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Hoeve et al., 2009). This process, called parental monitoring, keeps parents apprised of their youths' activities, which in turn enables them to respond appropriately to misbehavior. Monitored youths are less likely to engage in substance use and delinquent behavior or spend time with deviant peers, as evidenced by cross-sectional, longitudinal, and intervention design studies (e.g., Barrera, Biglan, Ary, & Li, 2001; de Kemp, Scholte, Overbeek, & Engels, 2006; Dishion et al., 2003; Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Fletcher, Darling, & Steinberg, 1995; Hoeve et al., 2009; Laird, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2008; Simons-Morton, Hartos, & Haynie, 2004; Weintraub & Gold, 1991). Research has revealed a direct relationship between parental monitoring and youth outcomes (e.g., Barrera et al., 2001; Dishion et al., 1991; Patterson & Dishion, 1985), including disruption of links between deviant peer influences and youth substance use or antisocial behavior (e.g., Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996; Laird et al., 2008). Further, Dishion and colleagues (2003) found that parental monitoring served as a mediating process by which family interventions decreased youths' substance use and deviant peer influences.

Despite its importance, effective parenting alone cannot fully capture processes that promote engagement in a peer context of problem behavior. Broader conceptualizations of the family, particularly the network of parent and sibling relationships, help capture a more complete picture of family dynamics that either promote positive development or increase risk for problems (Mesman et al., 2009; Richmond & Stocker, 2008). Family contexts characterized by close relationships help create an overall climate of acceptance and support, which promotes positive socioemotional development (e.g., Grych & Fincham, 1990; Thompson & Meyer, 2007). However, the family relational context is not well understood because most past research has failed to include and study multiple family relationships. There is good reason to believe that youths have unique and meaningful relationships with their mother, father, and siblings, and each likely contributes to adolescents' development.

Relationships with parents are a key factor in youths' development. Youths who feel close to their caregivers tend to value their opinions more highly and are more likely to seek guidance for difficult situations (Ackard et al., 2006). They also spend more time with their family and have less opportunity to engage in deviant behavior (Crawford & Novak, 2008), a core dynamic underlying social control theories of adolescent delinquency (Hirschi, 1969). Parent–youth connectedness has been linked to decreased risk for a host of problems such as substance use, depression, bullying, early sexual relations, and suicide attempts, and is associated with increased youth success (Ackard et al., 2006; Flouri & Buchanan, 2003; Markham et al., 2003). Moreover, parent–adolescent relationship quality remains an important predictor of youth problem behavior, even when controlling for effective parenting practices (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Capps, & Zaff, 2006; Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, & Carrano, 2006).

The sibling subsystem also exerts an important influence on the development of youth problem behaviors, and it can occur in a variety of ways. Close relationships with siblings can be either protective or problematic, depending on whether the siblings are prosocial influences (e.g., Lamarche et al., 2006) or promote deviant behavior (Rowe & Gulley, 1992). For instance, youths who have siblings who use substances or engage in deviant behaviors are at risk for engaging in the same behaviors (e.g., Stormshak et al., 2004; Windle, 2000). Moreover, previous research investigating sibling collusion revealed that these relationships often are characterized by positive affect that predicts increases in problem behavior (Bullock & Dishion, 2002). On the other hand, a dynamic of hostility or conflict in the sibling relationship consistently reflects lack of support and is linked with problematic outcomes, including involvement with delinquent peers and externalizing behaviors (Kim, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999), antisocial behavior (Bank, Burraston, & Snyder, 2004; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), and substance use (East & Khoo, 2005). Taken together, mounting evidence supports the idea that youths who feel connected to their family, including their siblings, are positioned for adaptive development during adolescence.

A broader, more systemic evaluation of family dynamics could provide a more thorough and generalizeable understanding of the contributions of family processes to adolescent outcome. Although accumulating evidence is establishing links between parenting, parent–adolescent relationships, and sibling relationships in terms of predicting adolescent problem behavior, the research is not without limitations. With rare exceptions, three are noteworthy in the current literature: (a) the unique contributions of mothers, fathers, and siblings are obscured because they rarely are evaluated simultaneously as unique predictors of youth problem behavior; (b) it is difficult to disentangle effective parenting and parent–youth relationships; and (c) it is difficult to generalize research on family relationships beyond the scope of intact families.

Historically, research on family relationships has largely focused on the mother–child relationship and thus has narrowly defined the family context (Thompson & Meyer, 2007). Despite growing recognition and study of other relationships in the family, information about the unique impact of distinct relationships within the family, apart from other relationships, remains sparse. Most previous research that has evaluated mother–youth and father–youth relationships has used separate analyses or combined these relationships into a single variable (Buist, Deković, Meeus, & van Aken, 2004; Goldstein, Davis-Kean, & Eccles, 2005; Reitz, Deković, & Meijer, 2006; Soenens, Vansteekiste, Luyckx, & Goossens, 2006). Rare exceptions to these approaches suggest that mother–youth and father–youth relationships each have a significant, unique impact on youth outcomes (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Capps, et al., 2006; Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, & Carrano, 2006; Flouri & Buchanan, 2003). Similarly, parent–youth and sibling–youth relationships are typically studied separately. Evidence from some studies suggests that sibling relationships have a unique impact on adolescent outcomes beyond that of parenting practices (Bank et al., 2004; Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2003; Richmond & Stocker, 2008; Williams, Conger, & Blozis, 2007). However, these studies typically used combined parenting variables (mother plus father) or focused only on parenting practices, without accounting for the parent–youth relationship. The logical next step is to test effective parenting and the unique effects of youths' relationships with their mother, father, and siblings as unique predictors of adolescent problem behaviors, to know whether these relationships have unique implications for youth development.

Second, family relationships typically have been studied apart from parenting practices. Because the quality of parenting practices such as parental monitoring often relies on the quality of the parent–child relationship (Kerr & Stattin, 2000), it is important to disentangle these dimensions to identify which processes most directly affect positive youth development. Two publications drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth support the idea that understanding the unique relationships between mother's and father's monitoring and parent–youth relationship quality contributes to the prediction of youth problem behaviors (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Capps, et al., 2006; Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, & Carrano, 2006). However, these studies focused on the onset of substance use and delinquent behavior during a wide age span of adolescence (as old as age 18) and cannot address questions about the degree of change over time or evaluate adolescents who were engaging in those behaviors prior to the first wave of data collection. Although the findings provide valuable information, it is also important to study youths who engage in substance use from an early age, which can be accomplished through the use of other methods. Other researchers have examined related questions, but typically have averaged mother and father variables into single “parenting” composites. For example, Vieno, Nation, Pastore, & Santinello (2009) studying a large cross-sectional sample of 840 Italian adolescents, a close parent–youth relationship and effective parental monitoring were uniquely and concurrently associated with youths' antisocial behavior. Clearly, additional research is needed to better understand how parenting and parent–child relationships function over a developmental period of high risk for growth in early problem behavior.

Because the number of youths who have nonresident parents continues to grow, studies that use data that are predominantly or entirely from intact families are increasingly less representative of family processes and relationships that contribute to youth problem behavior. There is good evidence that living in an intact family is linked with lower risk for problem behavior onset. However, this approach does not adequately address the process by which living in intact or nonintact families affects the nature of the relationships among family members. Not only may there be differences in the degree of impact of the father–youth relationship in intact versus nonintact families (Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Capps, et al., 2006), but the impact of all family relationships may be different across these contexts and is a question that warrants further investigation.

This Study

This study investigated the impact of parental monitoring and of youths' relationships with their mother, father, and siblings as unique predictors of change in youths' problem behaviors by using a prospective, autoregressive longitudinal design that followed youths from 6th to 8th grade. We focused on the progression of youths' antisocial behavior, substance use, and affiliation with deviant peers as key outcomes, because of their salience during this developmental period. Building on evidence supporting each of these dimensions as important predictors of youth problem behavior, we hypothesized that (a) greater parental monitoring would be associated with decreases in problem behavior over time, (b) mother–youth and father–youth connectedness would be associated with decreases in problem behavior over time, (c) conflict with siblings would be associated with increased problem behavior by 8th grade, and (d) the strength of the association between parent-youth relationships would differ as a function of residing with targeted parents.

Method

Participants

A subsample of a larger study of 593 adolescent participants from the 6th grade classes of three public middle schools in a midsized city in the Pacific Northwest was followed through 8th grade. The sample was recruited in two cohorts during subsequent academic years (Cohort 1, n = 378; Cohort 2, n = 215). Parents actively consented to participation, and students provided assent on the day of assessment administration. The overall sample comprised 51% males and 49% females and was ethnically diverse: White (36%), Latino/Hispanic (18%), African American (15%), Asian (7%), American Indian (2%), Pacific Islander (2%), biracial/mixed ethnicity (19%), and unknown (1%). After the 6th grade student surveys were collected, students and their families were randomly assigned to an intervention group or to a control group, taking into consideration self-reported student ethnicity and gender.

Of the 386 families randomly assigned to the intervention condition of the larger study, 179 (54% male, 46% female) elected to participate in supplemental youth and parent surveys; they comprised this study's subsample. Independent samples _t_-tests revealed no mean differences on outcome variables for this subsample and the larger intervention group at 6th or 8th grade. This subsample comprised youths who described themselves as White (36%), Latino/Hispanic (20%), African American (16%), Asian (3%), American Indian (2%), Pacific Islander (2%), or biracial/mixed ethnicity (21%). Annual family income reported by family caregivers ranged from less than 5,000togreaterthan5,000 to greater than 5,000togreaterthan90,000, with a median rating of 40,000to40,000 to 40,000to49,999.

Procedure

Dependent variables were assessed in a school survey given to all participants in the study. This school survey was derived from an Oregon Research Institute survey and questionnaires used in prior research (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003; Metzler, Biglan, Rusby, & Sprague, 2001). The school surveys were collected in the spring during class time, at Wave 1 (6th grade) and Wave 3 (8th grade). If a family moved away from the area, the survey was mailed to them. Youths were paid $20 for participation in the school survey at each wave. Subsample retention was 88% (n = 157 in 8th grade).

Supplemental teen and parent surveys were given to the families comprising the subsample analyzed in this study. Youths completed surveys about sibling conflict and about their connectedness with caregivers, and parents reported about monitoring. Separate consent forms were collected for these family assessments. Parent survey data were collected using an interview format, and the teen surveys were partially administered as interviews and partially completed by the teens. Parents were paid $100 for participation in the supplemental assessments. Procedures followed for this study were approved by the university institutional review boards for studies involving human participants.

Measures

Parental monitoring

Youths' primary caregivers completed a 10-item parental monitoring scale (Stormshak, Caruthers, & Dishion, 2006a) during which they indicated how often they knew who their child spent unsupervised time with, where their child spent free time, and how the child was doing in school. Items are presented in Table 1. This scale demonstrated adequate reliability (α = .82).

Table 1. Items for Parental Monitoring and Youth Connectedness with Caregivers Scales.

| Scale | Item |

|---|---|

| Monitoring | How often do you call to talk with parents of [child's] friends? |

| How often do you know the following? | |

| What she/he does during his/her free time | |

| Who she/he hangs out with during his/her free time | |

| If she/he does something bad outside the home | |

| How she/he does in different subjects at school | |

| Where she/he goes when she/he is out with friends at night | |

| Where she/he goes and what she/he does after school | |

| What she/he is doing when she/he is away from home | |

| If she/he keeps secrets from you about what she/he does during his/her free time | |

| She/he keeps information from you about what she/he does during nights and weekends | |

| Connectedness | How much would you miss [caregiver] if you did not see or talk to them for 1 month? |

| How much do you trust [caregiver] to follow through with commitments and to take your needs and your future seriously, regardless of their own problems or interests? | |

| How much do you respect [caregiver] and care about what they think? | |

| How much do you consider [caregiver] a role model and want to be like them when you grow up? | |

| To what extent would you seek advice or accept advice and guidance from [caregiver]? | |

| When [caregiver] disciplines you, or guides you, how fair and skillful do you think s/he is at it? | |

| Does [caregiver] pay attention to what you are doing, care about your activities, ask questions about your life and monitor how you are doing? | |

| Do you tell [caregiver] the truth about your life and behavior, trusting what s/he does with the information and how s/he reacts? | |

| Is [caregiver] someone that you enjoy being with, that you would like to go places and do things? |

Connectedness with caregivers

Youths completed the Connectedness with Caregivers subsection of the teen supplemental survey (Stormshak, Caruthers, & Dishion, 2006b), which involved a two-step process. First, youths listed up to five “caring adults” in their lives, in order of importance, using an open-response format. Second, youths responded to 9 items assessing their connectedness to each of the caregivers separately, a process designed to capture the degree to which they felt close to and trusted their caregivers, valued their opinions, relied on the caregivers for advice, and enjoyed spending time with them. Items, which are reported in Table 1, were rated on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 to 9, with anchors relevant to each question (e.g., I would not miss them to very much, I would be upset).

If youths excluded their biological mother or father from the list of important caregivers, they were asked four questions to assess whether they had any contact with their biological parents. These items asked youths to rate how frequently they had in-person contact, talked to each other on the phone, sent emails or letters, or received emails or letters. Each item was rated on an 8-point scale ranging from 1 (never) and 2 (less than once a year) to 8 (more than 3 times a week). If youths excluded a biological parent from the list of caregivers and endorsed never for all four items, indicating no contact, their connectedness scores were treated as missing data. If youths excluded parents with whom they reported having contact, they were assigned a score of 0 for their connectedness with that parent. Connectedness with mothers (α = .90) and fathers (α = .87) demonstrated adequate reliability.

Sibling conflict

Youths also rated items about levels of conflict with an identified sibling. Of those with siblings, 54.7% reported being closest with older siblings, and 45.3% felt closest to younger siblings. Youths identified sisters (45.3%) or brothers (54.7%) as their closest sibling. Also, 29.8% of siblings were sister–sister pairs, 22.4% were brother–brother pairs, and 47.8% were mixed-sex sibling pairs. After identifying a sibling that the youth felt closest to, two items regarding the frequency of arguments and of physical fights with the identified sibling in the past two months were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Items were highly correlated (r = .49, p < .001) and were averaged to create a single index.

Adolescent problem behaviors

Three subscales from the 6th and 8th grade school surveys were used to create a problem behavior composite: antisocial behavior, adolescent substance use, and deviant peer association. To assess antisocial behavior, youths completed 11 items assessing antisocial behavior during the past month. These behaviors included lying to parents about where they had been, skipping school without an excuse, purposely damaging or trying to damage property, and getting into fights. Items were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times) and yielded adequate reliability (α = .84).

For assessment of adolescent substance use, youths reported about their tobacco and alcohol use. Tobacco use was assessed with two items: “In the past month, how many cigarettes have you smoked?” and “In the past month, how many times have you used chewing tobacco or snuff?” Alcohol use was assessed with one question: “In the past month, how many drinks of alcohol have you had?” Drinks were defined as one glass of beer or wine or one shot of hard liquor. The tobacco items were averaged and _Z_-scores of the tobacco and the alcohol scores (r = .39, p < .01) were combined to create a single substance use indicator. _Z_-scores were computed on the basis of the original sample to allow for comparisons with the subsample.

Finally, youths provided information about deviant peer relationships by rating their peers' problem behaviors during the past month. This subscale comprised five items asking whether their friends got in trouble a lot, fought a lot, stole things, smoked cigarettes or chewed tobacco, or used alcohol or drugs. Students rated their friends' behavior on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (more than 7 times). This scale had adequate internal consistency (α =.73).

Results

Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted in several steps. First, means, standard deviations, and correlations were computed for the variables of interest, along with the frequency with which youths reported connectedness with caregivers, for descriptive purposes. Second, to evaluate whether the sample could be analyzed as a whole, between-group comparisons were conducted on the basis of youths' gender and family composition. Third, a measurement model of youths' problem behaviors was computed. Finally, the structural model was computed.

Descriptive Analyses

Correlations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. Family variables generally were associated in expected directions. First, family dimensions were examined. Parental monitoring was associated with greater youth connectedness with their mother (r = .17, p <.05) and with their father (r = .20, p < .05) but was unrelated to sibling conflict (r = .01, ns). Youths who felt connected with their mother also felt more connected with their father (r = .35, p < .01), and mother connectedness was associated with less sibling conflict (r = −.23, p < .05) but father connectedness was not (r = −.07). Outcome measures evidenced modest stability over time, with correlations ranging from .19 to .34 (p's < .05). Finally, several significant associations were found between family dimensions and youths' outcomes at 8th grade. Monitoring was associated with lower levels of antisocial behavior (r = −.32, p < .01) and deviant peer relationships (r = −.24, p < .01), but not with substance use. Mother connectedness was not correlated significantly with the outcomes, but father connectedness was associated with less antisocial behavior (r = −.25, p < .01) and fewer deviant peer relationships (r = −.22, p < .01) in 8th grade. Conflict with siblings was associated with greater levels of all three 8th grade outcomes (r's = .23 to .33, p < .01).

Table 2. Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Monitoring | — | |||||||||

| 2. Mom connect | .17* | — | ||||||||

| 3. Dad connect | .20* | .35** | — | |||||||

| 4. Sibling fight | −.01 | −.23* | −.07 | — | ||||||

| 5. Wave 1 antisocial | −.16* | −.16* | −.14 | .15 | — | |||||

| 6. Wave 1 deviant peer | −.12 | −.24** | −.17* | .27** | .60** | — | ||||

| 7. Wave 1 substance use | −.04 | .01 | −.04 | −.03 | .14 | .09 | — | |||

| 8. Wave 3 antisocial | −.32** | −.15 | −.25** | .23** | .26** | .44** | −.05 | — | ||

| 9. Wave 3 deviant peer | −.24** | −.07 | −.22* | .33** | .11 | .34** | .00 | .55** | — | |

| 10. Wave 3 substance use | −.09 | −.11 | −.17 | .30** | .04 | .12 | .19* | .37** | .27** | — |

| M | 3.97 | 7.22 | 6.81 | 1.40 | 1.17 | .52 | −.09 | 1.30 | 1.19 | −.11 |

| SD | .75 | 2.05 | 2.45 | .94 | .29 | .80 | .12 | .44 | 1.39 | .40 |

As previously described, youths used an open-response format to identify up to five important adults in their lives. The focus of this study was youths' ranking of their biological mother and father to evaluate parent–youth connectedness. For descriptive purposes, youths' rankings of their mother and of their father are provided. In this subsample, 4.5% (n = 8) of youths reported no contact with their biological mother and 22.5% (n = 40) reported no contact with their biological father. Of those youths who reported any contact with their biological mother, 94.9% identified their mother as an important caregiver in their lives. Within this group, youths ranked their mother as one of five most important caregivers in their lives: 79.2% of youths ranked their mother as the most important caregiver, 7.3% ranked her second, 2.2% ranked her third, 1.7% ranked her fourth, and 0% ranked her fifth. Of those youths who reported any contact with their father, 92.3% identified their father as an important caregiver in their lives. Within this group, 8.2% ranked their father as the most important caregiver, 52.2% ranked him second, 4.5% ranked him third, 3.4% ranked him fourth, and 2.2% ranked him fifth.

Then, _t_-tests were computed to evaluate whether there were mean-level differences for boys and for girls for the variables of interest. Boys and girls did not differ in their ratings of connectedness with mothers, connectedness with fathers, sibling conflict, or the 6th and 8th grade outcome indicators antisocial behavior, substance use, and peer deviance. Similarly, primary caregivers of boys did not differ from those of girls on their ratings of monitoring.

In this sample, 55.9% (n = 100) of youths reported living with both biological parents, 33.0% (n = 59) reported living with their biological mother only, 4.5% (n = 8) were living with their biological father only, and 6.1% (n = 11) reported not living with either of their biological parents. Residence with parents was examined as a distinguishing factor for variables of interest. First, those youths living with both biological parents in 6th grade were compared with youths from other family compositions on outcome variables at 6th and 8th grade time points. In 6th grade, youths living with both biological parents had significantly lower initial levels of antisocial behavior, t(174) = −2.21 p < .05 and affiliation with deviant peers, t(175) = −2.13, p < .05, but not substance use, t(176) = .76, ns. By 8th grade, these differences were no longer present for any of the Wave 3 outcome variables, t's(155) = −.074 to −1.58, ns.

Residence with biological parents also was examined in terms of parental monitoring and family relationships. Primary caregivers of youths living with both biological parents reported significantly lower levels of monitoring than did caregivers of youths living in other family constellations, t(161) = 3.02, p < .01, but these groups did not differ on youths' perceptions of conflict with siblings, t(158) = −.57, ns. Living with caregivers was important for maintaining connections with them. Youths living with their biological mother reported feeling more connected to them than did those who did not, t(168) = 9.92, p < .01. Similarly, youths living with their biological fathers felt more connected to them than did those who did not, t(136) = 3.01, p < .01.

Evaluation of the Full Model Predicting Problem Behavior

Next, we included both parental monitoring and the quality of family relationships in an autoregressive model predicting problem behavior through the middle school years. These analyses were conducted in three steps. First, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the measurement model of the outcome variables studied. Second, an autoregressive longitudinal model was computed to predict changes in youths' problem behaviors over time. Then, group comparisons were conducted to evaluate whether this model differed for boys and for girls. Structural models were computed using Amos 16.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). Model fit was assessed for each model tested, with preference given to models with nonsignificant χ2 values, comparative fit index (CFI) values of greater than .95, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) values of greater than .95, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values of less than .06.

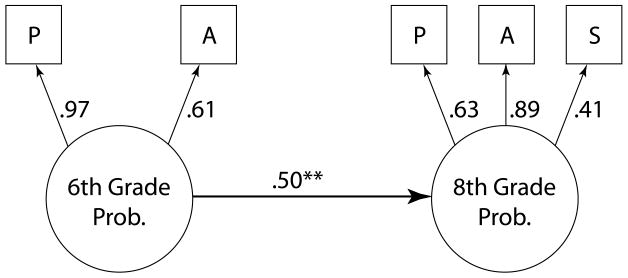

In the first step, the measurement model was evaluated for the latent constructs of youth problem behaviors at 6th and 8th grades. This model provided good fit with the data, χ2(5) = 6.40, p = .29; χ2/df = 1.279; CFI = .99; TLI = .97; RMSEA = .040. Inspection of the model revealed that each of the three indicators had a significant loading on the constructs, with the exception of Wave 1 substance use. This was likely a result of the low frequency of substance use reported by 6th grade students (5 of 179 reported any use), and this indicator was removed from the model without significantly altering the fit with the data, χ2(3) = 4.77, ns. Thus, 6th grade problem behavior was derived from youths' antisocial behavior problems and deviant peer affiliation, and the 8th grade problem composite also included substance use (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Note. χ2(4) = 84.841, p = .30; CFI = .995; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .034

A = Antisocial Behavior, S = Substance Use, P = Deviant Peer Affiliation

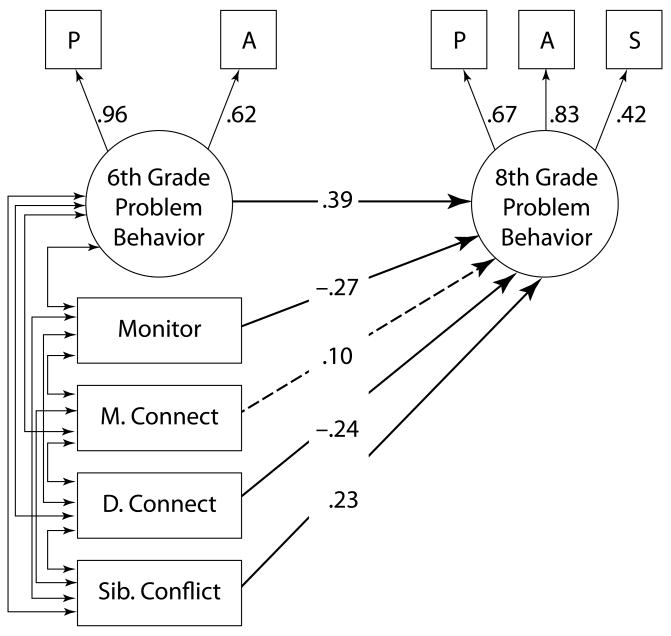

Then, an autoregressive model was computed evaluating parental monitoring, mother–youth connectedness, father–youth connectedness, and sibling conflict as predictors of 8th grade youths' problem behaviors, accounting for 6th grade problem behaviors. Correlations among the predictors were included to help account for shared variance and provide a clear test of the unique associations of each with youths' problem behaviors over time. Because of a Heywood case, variances of the Wave 1 problem behavior residuals were constrained to be the same, with no significant change to model fit, _χ_2(1) = .49, ns. The resulting model yielded good fit with the data, as shown in Figure 2, _χ_2(17) = 22.97, p = .15; CFI = .98; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .044. Overall, this model accounted for 44% of the variance in youths' 8th grade problem behaviors. Youths' problem behaviors were moderately stable over time (β = .39, p < .01). Examination of the predictors indicated that several dimensions of family functioning accounted for changes in youths' problem behaviors over time. As expected, when parents were able to use effective monitoring of their child's activities, youths reported decreases in problem behaviors by 8th grade (β = −.27, p < .01). After accounting for effective parenting, youths' relationships with family members also were associated with changes in youths' problem behavior. Youths who reported feeling connected with their father reported decreases in problem behaviors over time (β = −.24, p < .01); however, no significant association was found for mother–youth connectedness (β = .10, ns). Finally, conflict with siblings also was associated with escalations in youths' problem behavior over time (β = .23, p < .01).

Figure 2.

Note. χ2(17) = 22.971, p = .15; CFI = .98; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .044

8th Grade Problem Behavior _R_2 = .44

A = Antisocial Behavior, S = Substance Use, P = Deviant Peer Affiliation, Monitor = Parental Monitoring, M. Connect = Mother Connectedness, D. Connect = Father Connectedness

Group Comparisons of Youth Gender, Sibling Pairs, and Family Composition

Although there were no significant mean differences among the variables for boys and for girls, it is still possible that the relationships among the variables may differ by child gender. To evaluate this possibility, a group comparison model was computed to evaluate whether paths between predictors and 8th grade problem behaviors differed for boys and for girls. When paths predicting 8th grade problem behaviors were constrained to be the same for boys and for girls, the invariance model yielded adequate fit, suggesting that the paths were not significantly different, χ2(37) = 37.85, p = .43; CFI = 1.00; TLI = .99; RMSEA = .011. Similarly, we conducted group comparisons for sibling pair composition (i.e., sister–sister, brother–brother, or mixed-sex pairs). This model also provided a good fit, suggesting that models did not differ across these groups, χ2(58) = 61.250, p = .36; CFI = .98; TLI = .96; RMSEA = .019.

Then, to address the question of whether the paths differed in terms of family composition, groups were created to compare families with two biological parents in the household, with other family arrangements (i.e., living with one biological parent or no biological parents). After constraining paths to be equal across groups, the invariance model demonstrated adequate fit with the data, suggesting that the paths did not differ across groups, _χ_2(37) = 46.54, p = .14; CFI = .97; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .038.

Discussion

The results of this study support the view that parental monitoring and family relationships each have important preventive roles relevant to youths' engagement in antisocial behavior, substance use, and deviant peer groups. Taken together, these problem behaviors are developmentally salient issues during middle school and have important long-term implications for youth development in that they are predictive of high school success, later arrests and violent offenses, and substance abuse problems (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). Using a prospective, longitudinal design, we found the impact of parental monitoring, parent–youth relationships, and sibling conflict to be important predictors in the onset and progression of youth problem behaviors from 6th to 8th grade. Because this study evaluated each of these dimensions simultaneously and accounted for child gender and residency and nonresidency of fathers, it contributes significantly to the existing body of research.

Consistent with the results of past research, parental monitoring was found to be associated with decreases in youth problem behavior over time. This finding supports the view that effective monitoring is a cornerstone parenting practice during early adolescence and highlights the importance of attending to youths' activities, tracking their whereabouts and behavior, and structuring their environment (Barrera et al., 2001; Dishion et al., 1991; Hoeve et al., 2009). Questions have been raised about conceptualizations of monitoring as a parenting construct, because it is heavily reliant on youths' disclosure about their activities and peers (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Stattin & Kerr, 2000) and therefore heavily affected by the quality of the parent–youth relationship (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). This study addressed some of these concerns by simultaneously evaluating parental monitoring and youths' connectedness with caregivers to statistically disentangle these constructs. Even when evaluated in the context of family relationships, parental monitoring remained a significant predictor of decreases in youth antisocial behavior, substance use, and affiliation with deviant peers from 6th to 8th grade. This finding suggests that monitoring is a robust factor for explaining problem behavior development because it improves tracking and structuring of youths' activities (Dishion et al., 2003).

Family relationships in general, and father–youth connectedness and sibling conflict in particular, also predicted changes in youths' problem behaviors over time, after accounting for parental monitoring. In this study, family relationships were assessed to (a) capture dynamics in the family that either create an atmosphere of closeness, connection, and support, or distance and conflict, and (b) test the unique impact of mother–youth and father–youth connectedness and sibling conflict on the development of youths' problem behaviors. Our findings suggest that parent–youth and sibling relations each play an important role in early adolescent development and are consistent with findings from previous research that has investigated these relationships (e.g., Bank et al., 2004; Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2006).

Youths' connectedness with their parents was measured as drawing support and guidance from parents, trusting their advice, and feeling emotionally connected with them. Assessments that used an open-response format revealed that a reasonable minority of youths did not rate their biological parents as significant sources of care and support in their lives (8% of fathers, 5% of mothers), despite having ongoing contact with them. Regardless, levels of youths' ratings did not differ systematically in terms of youths' feelings of connectedness with their mother and their father.

Relevant to predicting youth outcomes over time, father–youth connectedness was associated with decreases in youths' problem behavior from 6th to 8th grade, after accounting for all other variables in the model. Mother–youth connectedness, however, was not a significant predictor of change, even in bivariate correlations with the 8th grade youths' outcomes. Taken together, these finding support the importance of evaluating youths unique relationships with their mother and fathers, and mirrors other work that has tested these parent-youth relationships as unique predictors, suggesting that they have distinct roles in terms of predicting youths' problems.

Further information is gained by examining father–youth connectedness with respect to child gender and family composition. Boys and girls did not differ in their ratings of closeness with their caregivers, and the nature of associations between father–youth connectedness and youths' outcomes did not differ by gender. In assessments relevant to effects of living with fathers, coresiding youths reported feeling more connected on average than did those who lived apart from their fathers, but the magnitude of the association between father connectedness and youths' outcomes did not differ as a function of living with fathers or not. These findings underscore the importance of father–youth connectedness regardless of child gender or whether fathers reside with youths, and suggest that future research into father prosocial involvement among divorced families would make a valuable contribution to the literature. Of note, there were no mean-level differences in boys' and girls' reports of problem behaviors among this sample, which is inconsistent with findings from most previous research (Dishion & Patterson, 2006).

The differences between mother–youth and father–youth connectedness revealed in this study should be interpreted with caution until these findings can be replicated, because they are inconsistent with previous studies investigating unique effects of mothers' and fathers' parenting practices or relationship quality with youths. Why father–youth connectedness, but not mother–youth connectedness, predicted changes in youths' problem behavior outcomes in this sample is difficult to clarify. This study used a different measure of parent–youth connectedness than previous studies have, but also analyzed data in terms of a broader array of family relationships than have other studies. The lack of mean-level differences in youths' reports of relationship connectedness with their mother and with their father suggests that the youths felt similar degrees of connectedness with each parent. Although the data in this study cannot explain why outcomes differed for mothers and for fathers (and warrants cautious interpretation), previous theory and research offer hypotheses. It is possible that mothers' and fathers' parenting roles differ in terms of susceptibility to change in response to family stressors (e.g., Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004), or that family dynamics between mothers and fathers shape father involvement (e.g., Pleck & Hofferth, 2008). Further research is needed to examine family interaction processes that can explain dynamics in mother–youth and father–youth relationships within the context of the family system. Nevertheless, our study findings indicate that youths fare better when the connection between fathers and their children is maintained.

Sibling conflict also significantly contributed to the development of youths' problem behaviors, after accounting for parental monitoring and connectedness with caregivers. As predicted, youths who reported more arguments or physical fights with their siblings also reported increased problem behaviors by 8th grade, independent of the effects of parental monitoring and parent–youth relationships. Although previous research has underscored the negative impact of associating with antisocial or deviant siblings (e.g., Stormshak et al., 2004; Windle, 2000), this study's findings provide further evidence that frequent conflict with siblings is also a risk factor for problem behavior development (Bank et al., 2004), even after accounting for youths' relationships with their parents and levels of parental monitoring. Interestingly, the impact of sibling conflict did not differ as a function of gender composition of sibling pairs. These study findings are consistent with the view that the sibling subsystem may contribute to the overall family environment by creating greater coercion, conflict, and hostility (Ingoldsby, Shaw, Owens, & Winslow, 1999). These factors may shape aggressive behavior, undermine parental involvement, and motivate youths to seek support and guidance outside of the home, where they are at greater risk for engaging in problem behaviors, experimenting with drugs, or associating with a deviant peer group (Patterson, Dishion, & Yoerger, 2000).

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this investigation used caregivers' and youths' reports on key variables, it relied heavily on youths' reports relevant to most of the constructs studied. The study reduced the effect of single-rater bias by using structural equation modeling, but this analytic approach does not eliminate the limitation. Future research would benefit from a multimethod, multi-informant approach. In particular, observational methods would help broaden the assessment strategy for important constructs such as parental monitoring, parent–youth relationships, and sibling relationships.

Although from a family systems perspective this study advances current understanding by effectively incorporating mother, father, and sibling influences on youths' development, this approach does not fully capture the family environment in which youths reside. Future research would benefit from a broader assessment of family functioning, such as interparental conflict (e.g., Fosco & Grych, 2007) or family cohesion or positivity (Thompson & Meyer, 2007), to more fully account for the family context. By incorporating broader dimensions of family functioning, it may be possible to better understand the dynamics at work between different subsystems that shape children's family environment and promote youths' development (e.g., McBride et al., 2005).

Limitations in the data collected prevented an evaluation of bidirectional processes relevant to parent–youth connectedness and youth problem behaviors. This is important for two reasons. First, adolescent problem behaviors may drive the deterioration in parent–youth relationships during the middle school years (Hafen & Laursen, 2009). Also, when studying parental monitoring, Kerr and Stattin (2003) suggest that monitoring may capture child behaviors as much as it does effective parenting. Future research is needed to expand upon the findings of this study to better examine the interdependence of family and youth functioning.

Second, our study could not account for concurrent effects of family dimensions in 8th grade when testing longitudinal cross-lagged effects. Previous studies that used a longitudinal panel design have produced mixed results. For example, using a longitudinal panel design, Kiesner, Dishion, Poulin, and Pastore (2009) found that adding cross-lagged paths did not significantly improve the fit of the model over a model accounting only for concurrent associations at each time point and stability paths from ages 13 to 14. However, Vuchinich, Bank, and Patterson (1992) found the opposite: their stability model of parenting, antisocial behavior, and peer relations from age 10 (Time 1) to age 12 (Time 2) provided a significantly worse fit than one that included cross-lagged associations, although cross-lagged effects for parenting were not found. Finally, other studies have found reciprocal effects of cross-lagged effects of parenting relevant to youth behaviors when predicting antisocial behavior (Laird, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2003) and when predicting youth substance use (Stice &Barerra, 1995). Thus, there is reason to believe that our study findings are meaningful despite their inability to account for concurrent parenting associations at 8th grade. However, further longitudinal research using panel designs that account for concurrent and longitudinal associations at both time points is needed to better understand the nature of associations among these variables.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Despite its limitations, this study highlights the importance of considering parenting practices and family relationships—with parents and with siblings—as factors that deter the development of youth problem behavior. Although it is established that parenting and family relationships are important during the middle school years, this study underscores the unique, additive contributions of parenting practices, parent–youth relationships, and sibling conflict to youth problem behaviors. Study findings suggest that interventions aimed at reducing risk for adolescent participation in antisocial behavior, substance use, and deviant peer relationships can be enhanced if they promote parenting practices and father–youth relationships and reduce sibling conflict. Another finding with important potential implications is that the pattern of results did not differ for youths living with or without their biological fathers. As such, father–youth connectedness may have important protective implications for youths regardless of whether they live with their fathers. This finding suggests that inclusion of nonresident fathers is important for research designs, clinical intervention for youths and their families, and in the development of social policy aimed at preventing youths' antisocial behavior, substance use, and deviant peer affiliation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant DA018374 to the second author and grant DA018760 to the third author, both from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We gratefully acknowledge the families who participated in these studies and Cheryl Mikkola for her editorial support.

References

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Parent–child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 user's guide. Chicago: SPSS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Burraston B, Snyder J. Sibling conflict and ineffective parenting as predictors of adolescent boys' antisocial behavior and peer difficulties: Additive and interactional effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Biglan A, Ary D, Li F. Replication of a problem behavior model with American Indian, Hispanic, and Caucasian youth. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, McBride Murry V, Brown AC. Longitudinal direct and indirect pathways linking older sibling competence to the development of younger sibling competence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:618–628. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, Capps RC, Zaff J. The influence of father involvement on youth risk behaviors among adolescents: A comparison of native-born and immigrant families. Social Science Research. 2006;35:181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, Carrano J. The father-child relationship, parenting styles, and adolescent risk behaviors in intact families. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:850–881. [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Deković M, Meeus W, van Aken MAG. The reciprocal relationship between early adolescent attachment and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock BM, Dishion TJ. Sibling collusion and problem behavior in early adolescence: Toward a process model for family mutuality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:143–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1014753232153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford LA, Novak KB. Parent–child relations and peer associations as mediators of the family structure–substance use relationship. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:155–184. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Being adolescent: Conflict and growth in the teenage years. New York: Basic Books Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Raymond J. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4th. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 196–221. [Google Scholar]

- de Kemp RAT, Scholte RHJ, Overbeek G, Engels RCME. Early adolescent delinquency: The role of parents and best friends. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2006;33:488–510. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behavior. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K. The Family Check-Up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Owen LD. A longitudinal analysis of friendships and substance use: Bidirectional influence from adolescence to adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:480–491. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol 3 Risk, disorder, and adaptation. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family school and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DM, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in children's lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Khoo ST. Longitudinal pathways linking family factors and sibling relationship qualities to adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:571–580. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AC, Darling N, Steinberg L. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of mother involvement and father involvement in adolescent bullying behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:634–644. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Grych JH. Emotional expression in the family as a context for children's appraisals of interparental conflict. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:248–258. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE, Davis-Kean PE, Eccles JS. Parents, peers and problem behavior: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of relationship perceptions and characteristics on the development of adolescent problem behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:401–413. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive–contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(2):267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafen CA, Laursen B. More problems and less support: Early adolescent adjustment forecasts changes in perceived support from parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:193–202. doi: 10.1037/a0015077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze HJ, Toro PA, Urberg KA. Antisocial behavior and affiliation with deviant peers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):336–346. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3, Serial No 227):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Dishion TJ. Antisocial personality development. In: Beauchaine TP, Hinshaw SP, editors. Child and adolescent psychopathology. New York: Wiley Press; 2007. pp. 370–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bromell L, Tyson DF, Flint R. Developmental commentary: Ecological perspectives on parental influences during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:367–377. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, van der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JRM. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Owens EB, Winslow EB. A longitudinal study of interparental conflict, emotional and behavioral reactivity, and preschoolers' adjustment problems among low-income families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:343–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1021971700656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children's influence on family dynamics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J, Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Pastore M. Temporal dynamics linking aspects of parent monitoring with early adolescent antisocial behavior. Social Development. 2009;18:765–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Hetherington EM, Reiss D. Associations among family relationships, antisocial peers, and adolescents' externalizing behaviors: Gender and family type differences. Child Development. 1999;70:1209–1230. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist. 2003;58:457–465. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Parents' monitoring knowledge attenuates the link between antisocial friends and adolescent delinquent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Parents' monitoring-relevant knowledge and adolescents' delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development. 2003;74:752–768. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche V, Brendgen M, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Pérusse D, Dionne G. Do friendships and sibling relationships provide protection against peer victimization in a similar way? Social Development. 2006;15(3):373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Excobar-Chaves SL, Parcel GS, Harrist R, Addy RC. Family connectedness and sexual risk-taking among urban youth attending alternative high schools. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:174–179. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.174.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Brown GL, Bost KK, Shin N, Vaughn B, Korth B. Paternal identity, maternal gatekeeping, and father involvement. Family Relations. 2005;54(3):360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Stoel R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Koot HM, Alink LRA. Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalizing prlblems: differential susceptibility of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:625–636. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler CW, Biglan A, Rusby JC, Sprague JR. Evaluation of a comprehensive behavior management program to improve schoolwide positive behavior support. Education and Treatment of Children. 2001;24:448–479. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Nelson LJ, Madsen SD, Barry CM. The role of perceived parental knowledge on emerging adults' risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:847–859. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ. Contributions of families and peers to delinquency. Criminology. 1985;23:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Yoerger K. Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science. 2000;1:3–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010019915400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Hofferth SL. Mother involvement as an influence on father involvement with early adolescents. Fathering. 2008;6:267–286. doi: 10.3149/fth.0603.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz E, Deković M, Meijer AM. Relations between parenting and externalizing and internalizing problem behaviour in early adolescence: Child behaviour as moderator and predictor. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:419–436. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MK, Stocker CM. Longitudinal associations between parents' hostility and siblings' externalizing behavior in the context of marital discord. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:231–240. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Gulley BL. Sibling effects on substance use and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Hartos JL, Haynie DL. Prospective analysis of peer and parent influences on minor aggression among early adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:22–33. doi: 10.1177/1090198103258850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Luyckx K, Goossens L. Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: An integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:305–318. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1070–1083. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M. A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents' substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M. Antisocial behavior, delinquent peer association, and unsupervised wandering for boys: Growth and change from childhood to early adolescence. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1994;29(3):263–288. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2903_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Caruthers A, Dishion TJ. Child and Family Center Parent Survey. 2006a. Unpublished measure Available from the Child and Family Center, 195 W 12th Ave., Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Caruthers A, Dishion TJ. Child and Family Center Child Survey. 2006b. Unpublished measure Available from the Child and Family Center, 195 W 12th Ave., Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Comeau CA, Shepard SA. The relative contribution of sibling deviance and peer deviance in the prediction of substance use across middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:635–649. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047212.49463.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Meyer S. Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Vieno A, Nation M, Pastore M, Santinello M. Parenting and antisocial behavior: A model of the relationship between adolescent self-disclosure, parental closeness, parental control, and adolescent antisocial behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1509–1519. doi: 10.1037/a0016929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich S, Bank L, Patterson GR. Parenting, peers and the stability of antisocial behavior in preadolescent boys. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:510–521. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub KJ, Gold M. Monitoring and delinquency. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1991;1(3):268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Williams ST, Conger KJ, Blozis SA. The development of interpersonal aggression during adolescence: The importance of parents, siblings, and family economics. Child Development. 2007;78:1526–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]