Trpc1 Ion Channel Modulates Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway during Myoblast Differentiation and Muscle Regeneration (original) (raw)

Background: The PI3K/Akt pathway is involved in muscle development and regeneration.

Results: Knocking out Trpc1 channels or inhibiting Ca2+ fluxes decreases PI3K/Akt activation, slows down myoblasts migration and impairs muscle regeneration.

Conclusion: Trpc1-mediated Ca2+ influx enhances PI3K/Akt pathway during muscle regeneration.

Significance: The activity of PI3K/Akt pathway is modulated by intracellular Ca2+.

Keywords: Akt, Calcium, Migration, Muscle Regeneration, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, TRP Channels, Myoblast

Abstract

We previously showed in vitro that calcium entry through Trpc1 ion channels regulates myoblast migration and differentiation. In the present work, we used primary cell cultures and isolated muscles from Trpc1−/− and Trpc1+/+ murine model to investigate the role of Trpc1 in myoblast differentiation and in muscle regeneration. In these models, we studied regeneration consecutive to cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury and observed a significant hypotrophy and a delayed regeneration in Trpc1−/− muscles consisting in smaller fiber size and increased proportion of centrally nucleated fibers. This was accompanied by a decreased expression of myogenic factors such as MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin and of one of their targets, the developmental MHC (MHCd). Consequently, muscle tension was systematically lower in muscles from Trpc1−/− mice. Importantly, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway, which plays a crucial role in muscle growth and regeneration, was down-regulated in regenerating Trpc1−/− muscles. Indeed, phosphorylation of both Akt and p70S6K proteins was decreased as well as the activation of PI3K, the main upstream regulator of the Akt. This effect was independent of insulin-like growth factor expression. Akt phosphorylation also was reduced in Trpc1−/− primary myoblasts and in control myoblasts differentiated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ or pretreated with EGTA-AM or wortmannin, suggesting that the entry of Ca2+ through Trpc1 channels enhanced the activity of PI3K. Our results emphasize the involvement of Trpc1 channels in skeletal muscle development in vitro and in vivo, and identify a Ca2+-dependent activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway during myoblast differentiation and muscle regeneration.

Introduction

Tissue repair after wounding or injury is a common adaptative response that occurs in many physiological or pathological processes such as in several myopathies. In skeletal muscle, regeneration involves successive steps of satellite cells activation, proliferation, and differentiation, and finally leads to formation of regenerated myofibers. The process is regulated by basic helix-loop-helix myogenic regulatory factors (1, 2). These factors constitute the so-called MyoD family of proteins that contains four members: Myf5, MyoD, myogenin, and MRF4, the transcriptional activity of which is potentiated by myocyte enhancer binding factor 2 (3, 4). Activated satellite cells express Myf5 and MyoD during proliferation. MyoD expression leads cells to withdraw from cell cycle and start differentiation (5). At this stage, they express myogenin (6, 7). Members of the MyoD gene family induce transcription of many muscle specific genes such as MHC genes (8, 9). Two MHC isoforms are expressed during muscle development: embryonic and perinatal MHC (10). Myf5 and MyoD have been reported to specifically activate the expression of these MHCs during muscle regeneration (11).

Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs)3 are other important players in myoblast differentiation in vitro and in muscle regeneration in vivo (12–14). Stimulation by IGFs induces phosphorylation and activation of IGF receptor (15). This leads to recruitment of the phosphotyrosine-binding domain of insulin receptor substrates (IRS) and results in IRS phosphorylation on specific tyrosine residues (16). Activated IRS recruits and sequesters the p85 subunit of PI3K, liberating the p110 catalytic subunit. The active p110 subunit generates 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides which bind the pleckstrin homology domain of phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 and Akt inducing their membrane targeting (17–19). Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1phosphorylates Akt, which phosphorylates the mammalian target of rapamycin mTOR, which in turn, phosphorylates p70S6K and activates protein synthesis.

Finally, extracellular Ca2+ also is known to play an important role in muscle development. Indeed, it has been reported that migration and/or fusion which precedes myotubes formation require Ca2+ influxes (20, 21). It has been suggested that this Ca2+ influx occurs through T-type Ca2+ channels (22). We recently reported that the process also involved the type 1 canonical subfamily of Trp (transient receptor potential) channels. Indeed, using a knockdown strategy in vitro, we showed that Trpc1 channels were responsible for the increased Ca2+ influx observed at the onset of myoblast differentiation (23).

To investigate the role of Trpc1 channels during skeletal muscle regeneration in vivo, we used a model of cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury and compared muscle consecutive regeneration in adult Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice. We observed that Trpc1−/− mice presented a delayed regeneration (smaller fibers, higher proportion of central nuclei, delayed and diminished expression of myogenic transcription). We show that the lack of Trpc1 or the inhibition of Ca2+ entries reduces Akt phosphorylation and delays muscle cell differentiation. We suggest that the entry of Ca2+ through Trpc1 channels enhances the activity of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway and accelerates muscle regeneration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− Mice

Generation of Trpc1−/− mice has been described previously (24). Trpc1−/− and Trpc1+/+ were obtained from heterozygous animals. Trpc1−/− were compared with their Trpc1+/+ control littermates.

Muscle Injury

Three- to four-month-old Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a solution containing ketamine (10 mg·ml−1 Pfizer, Brussels, Belgium) and xylazine (1 mg·ml−1 Bayer HC, Diegem, Machelen, Belgium). Tibialis anterior (TA) and extensor digitorium longus (EDL) muscles were injured by intramuscular injection of 50 and 20 μl, respectively, of a solution containing 10 μm cardiotoxin from Naja Naja (Sigma) (unique injection after limb skin opening and identification of muscle; skin closed by surgical suture). Muscles were harvested after specific periods of time to investigate the rate of regeneration.

Mechanical Measurement

Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice were anesthetized deeply (see above) to preserve muscle perfusion during dissection of both TA and EDL muscles. Depth of anesthesia was assessed by the abolition of eyelid and pedal reflexes. After dissection, the animals were killed by rapid neck dislocation. This protocol has been approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Louvain (Brussels, Belgium).

EDL muscles were bathed in a 1-ml horizontal chamber superfused continuously with Hepes buffered Krebs solution (100% O2) containing the following: 135.5 mm NaCl, 5.9 mm KCl, 1.0 mm MgCl2, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 11.6 mm Hepes sodium, and 11.5 mm glucose, maintained at 20 ± 0.1 °C. One end of the muscle was tied to an isometric force transducer and the other was tied to an electromagnetic motor and length transducer (25). Stimulation was delivered through platinum electrodes running parallel to the muscles. Resting muscle length (L0) was adjusted carefully for maximal isometric force using 100 ms (EDL) maximally fused tetani. Force was digitized at a sampling rate of 1 KHz, using a PCI 6023E i/o card (National Instruments under a homemade Labview program). Tension was expressed relative to cross-sectional area, obtained by multiplying absolute force by the quotient “muscle fiber length (mm)/muscle blotted weight (mg)” and considering the fiber length equal to 0.5 × L0 (26). Maximal tension was then expressed as a percentage of contralateral noninjected muscle tension.

Histology Assessment

Histological investigations were performed on cardiotoxin-injured TA muscles after a period of 1 to 14 days of regeneration. Muscles were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde on ice for 4 h, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin as described previously (27). The size of muscle fiber sections was measured using a homemade planimetry program (200 fibers were counted per muscle).

Immunohistochemistry

Five-μm thick paraffin embedded sections of TA muscles at day 3 of regeneration were deparaffinated, rehydrated, and blocked using a 0.5% bovine serum albumin solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) during 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated at 4 °C overnight with mouse MHCd antibody (1:10, Novocastra, UK) diluted in blocking solution, washed three times in PBS for 10 min, incubated with an anti-mouse antibody coupled with alkaline phosphatase (1:50, Sigma) for 1 h, washed three times again, and revealed using alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). The reaction was stopped with Tris-EDTA solution, pH 8, and sections were fixed in formol and mounted with Mowiol (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA).

Measurement of Transcription Factor Activity

The global activity of myogenic transcription factors was measured using a luciferase plasmid gene reporter. The 4RTK-luciferase vector containing four oligomerized MyoD-binding sites upstream of a thymidine kinase promoter (28) (kindly provided by Dr. Steve Tapscott, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) was amplified in Escherichia coli TOP10F′ (Invitrogen) and purified with an EndoFree Plasmid Giga kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) (29). The day before injection, 30 μg of plasmid were lyophilized and resuspended in 30 μl of 0.9% NaCl solution. Three days before cardiotoxin injection, each mouse was anesthetized, and 1 μg/μl plasmid solution was injected into TA muscles; these were electroporated as described previously (30). At day one of regeneration, animals were sacrificed, and TA muscles were removed. Whole TA muscles were homogenized with Ultraturax (IKA-Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany), and luciferase activity was quantified using a luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were scraped off, rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS, centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and kept at −80 °C until use. Injured TA muscles were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and also kept at −80 °C until use. Cells pellets were suspended in 60 μl and TA muscles in 500 μl of lysis buffer containing the following: 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA (pH 8), 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm NaVO3, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm NaPPi, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche, Complete Mini) and 0.5% Nonidet P-40, homogenized with pipette tips for cells or Ultraturax for muscles and incubated for 10 min at 4 °C. Nuclei and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Samples were incubated with Laemmli sample buffer containing SDS and 2-mercaptoethanol for 3 min at 95 °C, electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were incubated with rabbit anti-Myf5 (1:1000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti-MyoD (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-myogenin (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-phospho-Akt (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), mouse anti-PKB/Akt (1:1000; Bioke, Leiden, Netherlands), rabbit anti-phospho- and total p70S6K (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). After incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody coupled to peroxidase (Dako, Heverlee, Belgium), peroxidase was detected with ECL plus on ECL hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences, Diegem, Belgium). Protein expressions were quantified by densitometry.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Injured EDL muscles were homogenized in TRIzol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was treated with DNase I and reverse-transcribed using qScript Reverse Transcriptase (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, ME). Gene-specific PCR primers were designed using Primer3. The GAPDH housekeeping gene and the genes of interest were amplified in parallel. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using 5 μl of cDNA, 12.5 μl of qScript Reaction Mix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) and 300 nm of each primer in a total reaction volume of 25 μl. Data were recorded on a DNA Engine Opticon real-time RT-PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) and cycle threshold (Ct) values for each reaction were determined using analytical software from the same manufacturer. Each cDNA was amplified in duplicate, and Ct values were averaged for each duplicate. The average Ct value for GAPDH was subtracted from the average Ct value for the gene of interest and normalized to non-injected muscles. As amplification efficiencies of the genes of interest and GAPDH were comparable, the amount of mRNA, normalized GAPDH, was given by the relation 2−ΔΔCt. MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin primers and GAPDH and growth factor primers were designed as described previously (31, 32).

Immunoprecipitation Assay

Protein extracts were prepared from C2C12 myoblasts cultured in differentiation medium for 1 day or from TA muscles after 3 days of regeneration. One μg of mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (BD Biosciences) was incubated with 40 μl of Sepharose G beads (Sigma) for 2 h at 4 °C and then incubated overnight with 300 μg of protein lysates. The lysates were removed, and the beads were washed with lysis buffer containing anti-protease and anti-phosphatase. Proteins were then eluted by boiling at 95 °C for 3 min in 40 μl of twice-concentrated SDS sample buffer. These samples were submitted to Western blot analysis using a rabbit anti-p85 PI3K antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling).

C2C12 Cellular Culture

C2C12 mouse skeletal myoblasts were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% non essential amino acids, and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. To induce differentiation, myoblasts were grown to ∼50–75% confluence, the growth medium was then replaced with differentiation medium, consisting of DMEM supplemented with 1% horse serum. To test the role of Ca2+ in differentiation, we loaded cells with EGTA-AM 20 μm for 3 h and kept them for 1 to 5 additional days in normal differentiation medium. Alternatively, the short term effect of Ca2+ was investigated by differentiating cells for 4 h in DMEM medium devoid of Ca2+ and supplemented with 1% horse serum and 200 μm EGTA.

Primary Myoblast Culture

One- to two-day-old Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice were used simultaneously. Muscles were harvested, minced with fine scissors, and centrifuged at 700 rpm for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pieces of muscles were incubated with 5 ml of F12-DMEM medium (Invitrogen) containing 0.1% of collagenase type I and 0.15% of Dispase II (Sigma) in a shaking bath maintained at 37 °C for 5 min during the first dissociation process to eliminate damaged fibers and then three times for 15 min. The supernatants of each dissociation were collected in 5 ml of F12-DMEM containing 30% FBS and 85 μg·ml−1 streptomycin and 85 units·ml−1 penicillin and placed on ice to stop the digestion. The three fractions of dissociation were then pooled in a 50-ml falcon tube and centrifuged at 700 rpm for 3 min. Supernatants were filtered using a 50-μm mesh nylon filter before preplating in Petri dishes for 30 min. Nonadherent cells were plated on culture flasks and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air. Differentiation was induced at 70% confluence by switching the proliferating medium to differentiation medium containing DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum.

Mn2+ Quenching Measurements

Myoblasts were loaded for 1 h at room temperature with the membrane-permeant Ca2+ indicator Fura-PE3/AM (1 μm). Cells were illuminated through an inverted Nikon microscope (40 × magnification objective) at 360 nm, and the fluorescent light emitted at 510 nm was measured using a Deltascan spectrofluorimeter (Photon Technology Intl.). To measure Ca2+ influx into myoblasts, 500 μm MnCl2 was added to the Krebs medium, and the influx of Mn2+ was evaluated by the quenching of Fura-PE3 fluorescence excited at 360 nm (isosbestic point) (33, 34).

Wound Healing Assay

The wound healing assay was performed as described previously (23). Briefly, proliferation of primary myoblasts at 70% confluence was stopped by switching to differentiation medium for 24 h. Then, cells were scrapped off to obtain a 600 μm wide acellular area and migrated myoblasts into this area were counted after 15 h using the ImageJ program.

Chemicals

Cardiotoxin I isolated from Naja Naja Atra was purchased from Sigma. Fura-PE3/AM, EGTA-AM, and wortmannin were obtained from Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany. F12/DMEM, DMEM, serum, and streptomycin-penicillin solutions were purchased from Invitrogen.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± S.E. Statistical significance was determined using t tests to compare two groups or analysis of variance to compare many groups. Analysis of the muscle cross-sectional area was performed using a χ2 Pearson test. The level of significance was fixed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

TRPC1−/− Mice Present Delay of Skeletal Muscle Regeneration

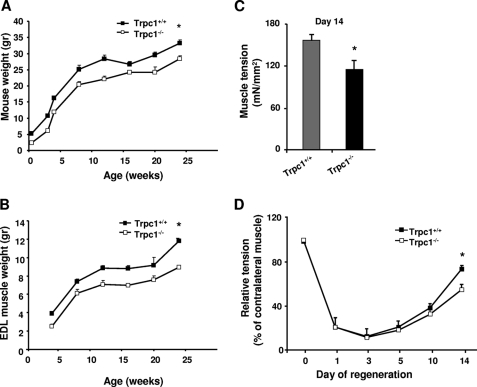

We previously showed that TRPC1 protein repression reduces C2C12 myoblast migration and differentiation (23). We also observed that Trpc1−/− mice presented a mild muscular hypotrophy consisting in smaller fibers size and in reduced content in myofibrillar proteins without any other sign of myopathy such as necrosis, central nulei, or fibrosis (27). Here, we studied animal development during the first six months of life and confirmed a moderate but significant default of development (Fig. 1A) with in particular a reduced of muscle weight progression (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Weight and tension of normal and regenerating muscle in Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice. A and B, animal and EDL muscle weights during the first 6 months of life (*, p < 0.05). C, maximal tension (force per cross-sectional area) measured after cardiotoxin-induced injury in EDL muscles at day 14 of regeneration, stimulated during 300 ms and at 125 Hz. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ (Student's t test, n = 6). D, time course of muscle tension in regenerating EDL muscles. Day zero is the day of cardiotoxin injection. Tension of regenerating muscle reported to that of contralateral noninjected muscle. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ (two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test for multiple comparison, n = 6 per day).

To further investigate whether deletion of Trpc1 protein can impair skeletal muscle development in vivo, we studied muscle regeneration after cardiotoxin-induced injury in Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice (35). EDL and TA muscles were harvested after different periods of time post-injury and were characterized functionally and histologically. First, we measured muscle tension of regenerated Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− muscles at day 14 of regeneration when muscle repair is almost completed (35). We observed that Trpc1−/− regenerating muscles presented about 25% lower tension than Trpc1+/+ muscles (114.47 ± 13.18 in Trpc1−/− versus 155.78 ± 9.11 mN/mm2 in Trpc1+/+; p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). To relate this difference of tension to a deficit of regeneration, we performed muscles tension kinetics in the two groups from the first to the fourteenth day of regeneration and related the tension produced by regenerating muscle to that produced by contralateral non injected muscle. We observed that one to 3 days after cardiotoxin injection, muscle tension was dramatically but similarly decreased in both Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− muscles (Fig. 1D). The importance of this loss of tension (∼10% residual tension) indicated that degeneration was almost complete in both groups. Interestingly, the time course of tension recovery between days 3 and 14 post-injury suggests that muscle regeneration is slower in Trpc1−/− than Trpc1+/+ mice (Fig. 1D).

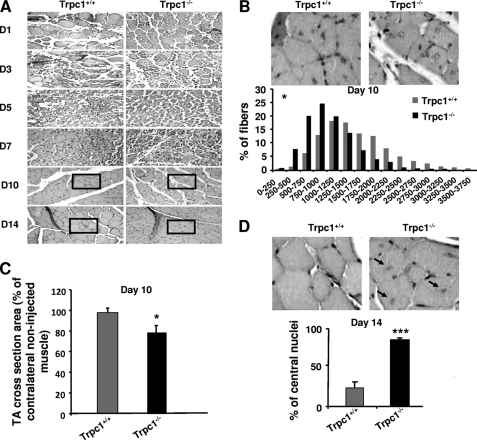

The apparent delay of recovery observed in Trpc1−/− muscles was corroborated results point to a delayed repair in Trpc1−/− muscles in comparison with Trpc1+/+ muscles: (i) adult non regenerated Trpc1−/− muscle fibers present a smaller cross-section area than Trpc1+/+ muscles (1317 ± 97 μm2 versus 1638 ± 103 μm2, n = 3 different animals of each type, 200 muscle fibers counted per muscle, p < 0.05). Ten days after cardiotoxin injection, this difference was more important (1041 ± 81 μm2 in Trpc1−/− versus 1638 ± 110 μm2 in Trpc1+/+ n = 6 different animals of each type, 200 muscle fibers counted per muscle, p < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Indeed, Trpc1+/+ muscle fibers had recovered a normal size (98% of nonregenerated fibers), whereas Trpc1−/− fibers remained significantly smaller than fibers from the contralateral noninjected muscle (Fig. 2C); (ii) at day 14 of regeneration, the majority of Trpc1−/− fibers were still centrally nucleated, whereas in Trpc1+/+ fibers most of the nuclei had migrated to the periphery (84.25 ± 2.30% central nuclei in Trpc1−/− versus 23.53 ± 7.55% in Trpc1+/+; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2D). Altogether, these results highlight a small but significant delay of muscle regeneration in Trpc1−/− mice compared with Trpc1+/+ mice.

FIGURE 2.

Histological characteristics of regenerating muscles after cardiotoxin injection. A, hematoxylin/eosin staining of TA muscles from Trpc1**+/+** and Trpc1−/− mice after cardiotoxin injection. B, detailed views of zones represented at day 10. Shown is a quantification of fiber size areas. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ (Pearson Chi square, n = 6 different mice). C, fiber size at day (D) 10 of regeneration related to contralateral noninjected muscle (*, p < 0.05, n = 6 TA muscles from six different mice, 200 fibers counted per muscle). D, detailed views of zones represented at day 14. The proportion of central nuclei is shown. Arrows indicate central nuclei. ***, p < 0.001 versus Trpc1+/+ (n = 3 different mice, three microscopic fields per muscle of each animal).

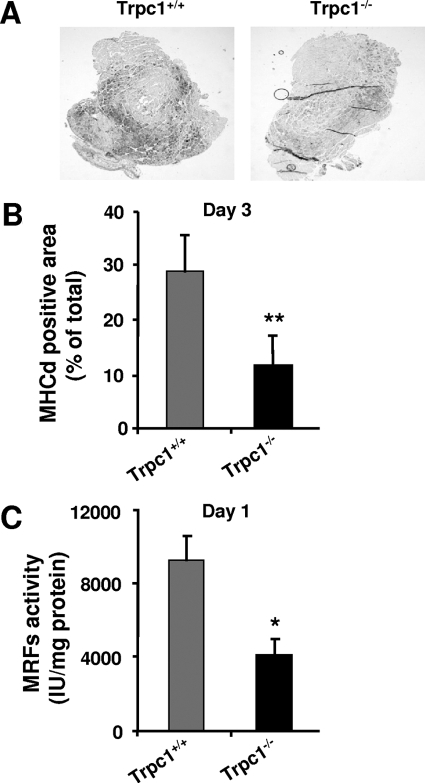

Expression and Activity of Myogenic Transcription Factors Are Decreased in Trpc1−/− Regenerating Muscles

To investigate the time course of regeneration, we measured the expression of developmental myosin heavy chains (MHCd) by immunohistochemistry. MHCd expression was absent in non regenerating muscles and began at day 3 of regeneration in both Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− muscles, but interestingly, the number of cells expressing the protein was much lower in Trpc1−/− than in Trpc1+/+ muscles (Fig. 3A). Quantification of the MHCd-positive area related to total muscle section area confirmed a significant decrease in MHCd expression in Trpc1−/− in comparison with Trpc1+/+ muscles (11.44 ± 2.71% versus 28.48 ± 6.47%, respectively) (Fig. 3B). The expression of MHC and other structural proteins requires the activation of their promoter by a group of myogenic basic helix-loop-helix factors such as MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4, which act at multiple points in the myogenic lineage to establish myoblast identity and to control terminal differentiation (3, 28, 29). The activity of these myogenic transcription factors was investigated using a luciferase plasmid gene reporter assay. We chose a luciferase plasmid encoding firefly luciferase under a promoter containing the binding site of the MyoD gene family and transfected it into TA muscles by electroporation. Luciferase expression revealed by luminescence can therefore be correlated to the activity of the myogenic transcription factor (37). The results presented in Fig. 3C indicate a significant decrease in the activity of these myogenic factors in Trpc1−/− regenerating muscles at day 1 compared with wild-type controls.

FIGURE 3.

Assessment of the activity of myogenic transcription factors. A, immunodetection of MHCd in TA muscles from Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice, 3 days after injury. B, quantification of MHCd positive areas related to total muscle cross-section area. **, p < 0.01 versus Trpc1+/+ (Student's t test, n = 6 different mice per group). C, myogenic transcription factors activity measured using a luciferase-based gene reporter, related to the quantity of muscle protein content. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ (Student's t test, n = 6 different animals).

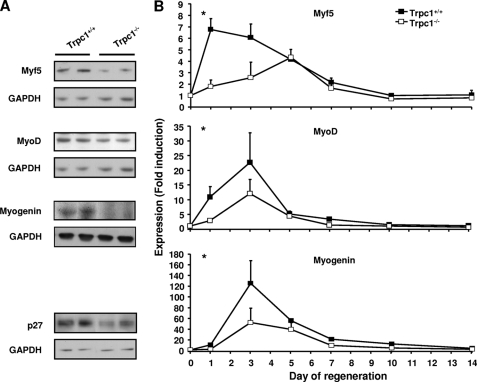

We therefore studied the time course expression of Myf5, MyoD, and myogenin. Quantitative PCR revealed a significant decreased and/or delayed expression of the three genes in Trpc1−/− muscles. This was also confirmed at the protein level (Fig. 4). We also observed a significantly decreased expression of p27, a well known cdk inhibitor, which in synergy with MyoD, induces a withdrawal from the cell cycle and initiates differentiation (38, 39).

FIGURE 4.

Expression of myogenic transcription factors in regenerating muscles. A, expression of myogenic factors (Myf5, MyoD, and myogenin) and p27 assessed by Western blot analysis in TA muscles. B, mRNA quantification (quantitative RT-PCR) of myogenic factors in EDL muscles. Δ_Ct_ was calculated by using GAPDH as internal control, and ΔΔ_Ct_ was related to the noninjected muscles in each group. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ at day 1 (two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's test for multiple comparison, n = 4 different animals per day).

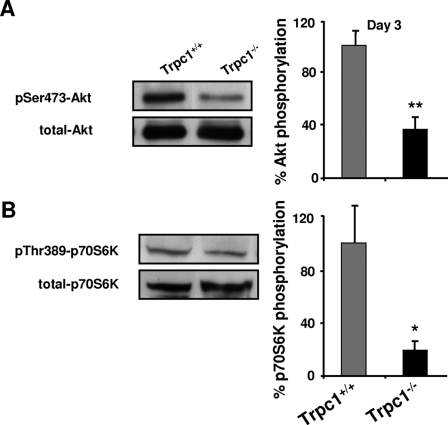

Akt/mTOR/p70S6K Pathway Is Down-regulated in Trpc1−/− Regenerating Muscles

The Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway is a crucial regulator of protein synthesis during muscle regeneration (40). In particular, mTOR is well known to regulate muscle fiber size (41). We observed a smaller fiber size in regenerating Trpc1−/− regenerating muscles in comparison with Trpc1+/+ and, in a previous work, also showed that adult Trpc1−/− skeletal muscles contain ∼20% less myofibrillar proteins than controls (27). We therefore investigated the activation of this pathway in our model by measuring the phosphorylation of Akt and p70S6K, acting respectively upstream and downstream mTOR. At the beginning of regeneration (day 3), we observed a very large decrease in phosphorylation of serine residue 473 of Akt (Fig. 5A) and of threonine residue 389 of p70S6K (Fig. 5B), in Trpc1−/− muscles compared with Trpc1+/+ muscles, indicating a clear down-regulation of this pathway in TRPC1−/− regenerating Trpc1−/− muscles.

FIGURE 5.

Akt pathway in regenerating muscles. The level of Akt and p70S6K phosphorylation was quantified in TA muscles at day 3 of regeneration using Western blot analysis and was related to total Akt and p70S6K proteins contents, respectively. **, p < 0.01 versus Trpc1+/+ (A); *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+ (B); Student's t test (n = 6 different animals).

Ca2+ Entry through Trpc1 Channels Modulates PI3K/Akt/p70S6K Pathway Activation During Muscle Regeneration

In muscle regeneration, the Akt pathway is essentially regulated by PI3K, which is recruited by IRS upon IGF stimulation (15). To investigate whether the decrease of Akt pathway activity was due to a decrease of IGF expression in Trpc1−/− muscles, we quantified by quantitative RT-PCR the expression of IGF1, IGF2, and MGF (the earliest isoform of IGF expressed during muscle regeneration) in the two groups of regenerating muscles. Results showed a similar expression level of all these growth factors (data not shown). In agreement with these results, we observed that the phosphorylation level of IRS was similar in Trpc1−/− and Trpc1+/+ muscles, suggesting that the diminished activity of the Akt pathway is not due to decreased IGF stimulation (data not shown).

This prompted us to investigate the role of PI3K in the activation of the Akt pathway and in particular the possible role of Trpc1 in the activation of this pathway. To decipher these mechanisms, we investigated two cellular models, the ex vivo primary muscle culture and the C2C12 cell line, allowing control of the ionic environment during muscle development and to perform cellular biophysical measurements more easily.

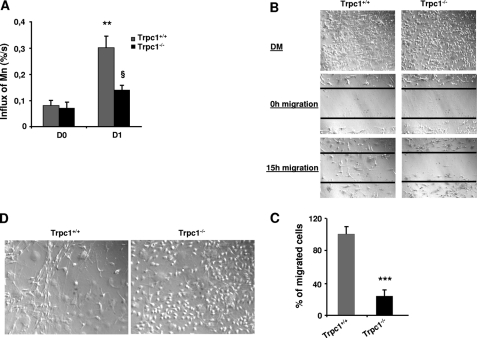

In our previous work, using a knockdown strategy with si- and shRNAs targeted against Trpc1, we observed a decrease in Ca2+ influx in Trpc1 knockdown myoblasts and consistently a decrease of myoblast migration and differentiation (23). Here, we compared the amplitudes of Ca2+ influx between Trpc1+/+ versus Trpc1−/− primary muscle cultures using Mn2+-induced quenching of Fura-PE3. We observed a similar level of Ca2+ influx at day zero of differentiation in the two groups, but after 24 h of differentiation, Ca2+ influx increased in Trpc1+/+ culture, and this was not observed in Trpc1−/− cultures (Fig. 6A). As can be expected, this caused a defect in myoblast migration (Fig. 6, B and C). In particular, we systematically observed that Trpc1−/− myoblasts maintained in differentiation medium for 3 to 5 days did not line up with each other like in Trpc1+/+ cells (Fig. 6D). All of these results confirmed our earlier results about the involvement of Trpc1 in Ca2+ homeostasis of differentiating myoblasts.

FIGURE 6.

Involvement of Trpc1 in calcium-mediated primary myoblast differentiation. A, calcium influx in Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− primary myoblasts estimated by using Mn2+-induced Fura-PE3 quenching technique. D0 represents proliferation condition, and D1 represents the first day of differentiation. **, p < 0.01 versus DO in Trpc1+/+ myoblasts; §, p < 0.05 between D1 Trpc1−/− and D1 Trpc1+/+ myoblasts (two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni test for multiple comparison). B, wound healing assay performed in primary cultured myoblasts obtained from Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− mice and maintained 24 h in differentiation medium (DM). C, number of migrating myoblasts 15 h after wounding (related to Trpc1+/+ migrating myoblast). ***, p < 0.001 versus Trpc1+/+ (Student's t test, representative data of three independent experiments). D, representative examples of Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− myoblasts maintained in differentiation medium for 4 days.

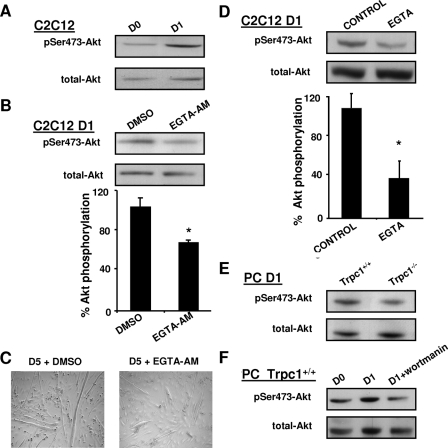

To investigate the impact of cytosolic Ca2+ on Akt pathway activation at the beginning of differentiation, we treated C2C12 myoblasts with EGTA-AM, an intracellular Ca2+ chelator. While under control conditions, Akt phosphorylation was enhanced at day 1 of differentiation (Fig. 7A), it was decreased by 40% in EGTA-AM-treated myoblasts (Fig. 7B). Moreover, 5 days after the beginning of differentiation, myotubes derived from EGTA-AM treated myoblasts (treated at day 1) appeared thinner than control myotubes (Fig. 7C). To discriminate whether cytosolic calcium involved in Akt pathway stimulation came from subcellular compartments or from the external medium, differentiation was induced in the same differentiation medium but devoid of Ca2+ and supplemented with EGTA. We observed that Akt phosphorylation was decreased significantly, suggesting that the effect of Ca2+ on Akt results from an influx from the extracellular compartment (Fig. 7D). Finally, we obtained similar results by comparing Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− myoblasts in primary culture, suggesting that Trpc1 protein is involved in the influx of calcium and the consecutive phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 7E). Akt phosphorylation was also inhibited by wortmannin, a well known inhibitor of PI3K (Fig. 7F).

FIGURE 7.

Ca2+ modulation of Akt activation. A, immunodetection of Akt phosphorylation in C2C12 myoblasts maintained in proliferation medium (day 0) or cultured 1 day in differentiation medium (day 1). B, immunodetection of phosphorylated Akt in C2C12 myoblasts treated 24 h with 20 μm EGTA-AM or vehicle only (dimethyl sulfoxide; DMSO), as a fraction of total Akt contents. *, p < 0.05 versus dimethyl sulfoxide; Student's t test (n = four different cultures). C, morphology of C2C12 myotubes after 5 days of differentiation; left panel, myoblasts treated with vehicle only; right panel, myoblasts treated at day 1 with 20 μm EGTA-AM. D, immunodetection of phosphorylated Akt in C2C12 myoblasts maintained 4 h in differentiation medium with or without Ca2+ (200 μm EGTA), as a fraction of total Akt contents. *, p < 0.05 versus control (Student's t test, n = 3 different cultures). E, comparison of phosphorylated Akt at day 1 of differentiation in Trpc1−/− and Trpc1+/+ primary myoblasts. F, immunodetection of phosphorylated Akt of Trpc1+/+ primary myoblasts cultured (PC) in proliferation medium (D0) and after 1 day in differentiation medium in the absence (D1) or in the presence of 100 nm wortmannin.

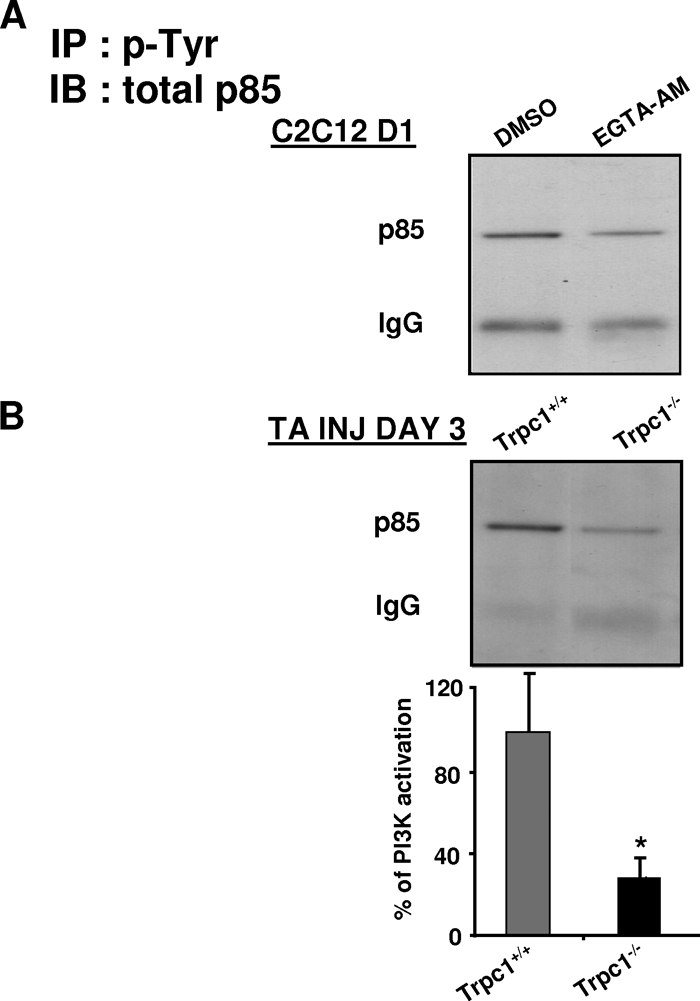

We therefore hypothesized that Ca2+ entry through the Trpc1 channel could contribute to activation of PI3K, which in turn, would activate the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway. The rate of PI3K activation, i.e. the rate of its recruitment on tyrosine-phosphorylated IRS, was evaluated by immunoprecipitation assay. Phosphotyrosines residues were immunoprecipitated and p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3K, was detected by immunoblot. As shown in Fig. 8A, treatment of C2C12 myoblasts by EGTA-AM decreased the activation of PI3K, suggesting the involvement of Ca2+ in PI3K activation in cultured myoblast differentiation. To confirm that this mechanism did also operate in vivo, we compared PI3K activation in regenerating Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− regenerating muscles. We observed a decrease of pP85 subunit recruitment onto phosphotyrosine residues in Trpc1−/− muscles, suggesting that Ca2+ entry through Trpc1 channels modulates PI3K activation during muscle regeneration (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Involvement of Trpc1 in PI3K activation. Immunoprecipitation of phosphotyrosines residues followed by immunoblot of p85 subunit of PI3K (A) in C2C12 myoblasts cultured 1 day in differentiation medium and treated with or without EGTA-AM (B) in Trpc1+/+ and Trpc1−/− TA muscles after 3 days of regeneration. *, p < 0.05 versus Trpc1+/+; Student's t test (n = 6 different mice).

DISCUSSION

Activation of the PI3K pathway is well known to induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy defined as an increase in pre-existing fiber size as opposed to fiber number. During muscle regeneration, the prohypertrophic effect of IGFs is dependent predominantly on the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Akt induces protein synthesis through the activation of p70S6K and blocks the up-regulation of two key mediators of muscle atrophy, the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1, and atrogin 1 (42, 43). The PI3K pathway seems also to be required in myoblast differentiation and may act downstream or in parallel with MyoD (44–47).

Previously, we showed that, at the beginning of muscle differentiation, Trpc1 was overexpressed and that this was responsible for the increased Ca2+ entry observed at day 1 of differentiation. In the present study, we observed a concomitant increase of Akt phosphorylation, suggesting that the entry of Ca2+ entering through Trpc1 plays a role in the activation of this pathway. In myoblasts derived from Trpc1−/− mice, the increased entry of Ca2+ and the phosphorylation of Akt were both inhibited. The latter effect also was mimicked when cytosolic Ca2+ transients were buffered by EGTA-AM or when myoblast differentiation was initiated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Similarly, regeneration of cardiotoxin-injected control muscles was accompanied by a phosphorylation of Akt and of its downstream target p70S6K. This was largely reduced in Trpc1−/− muscles (Fig. 5). As suggested by the effect of wortmannin (Fig. 7D), Akt is essentially under the dependence of PI3K at this stage of differentiation. We found that IGF mass or activity were not altered in regenerating Trpc1−/− muscles as compared with control muscles. However, PI3K activity was decreased in Trpc1−/− versus Trpc1+/+ at the beginning of differentiation, to an extent similar to the one when myoblasts were treated with EGTA-AM. This suggests that entry of Ca2+ through Trpc1 channels modulates PI3K activity.

As the PI3K/Akt/p70S6K pathway plays a major role in muscle regeneration and development, its down-regulation in the absence of Trpc1 channels may account for the delayed muscle mass and force recovery of Trpc1−/− regenerating muscles. In regenerating Trpc1−/− muscles, we also observed a decrease in the expression and the activity of intrinsic myogenic regulatory factors of the MyoD family, in particular MyoD, Myf5, and myogenin. The PI3K/Akt pathway has been shown to increase the transcriptional activity of MyoD (48–50). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that activated Akt specifically interacts with prohibitine 2, competing with its binding to MyoD and thus increasing MyoD transcriptional activity (45). Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway observed in Trpc1−/− muscles could therefore explain the reduced level of myogenin and MHCd, the expression of which depends on MyoD. Consequently, muscle cell maturation is delayed in Trpc1−/− mice after injury (Fig. 2C) as well as in normal myoblasts cultured after treatment with EGTA-AM.

In addition, Trpc1 also seems to be able to stimulate myogenesis independently of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Indeed, it has been reported that Trpc1 interacts with the inhibitor of the myogenic family, Imf-a. This competes with the binding of Imf-a to myogenin and causes releases of active myogenin, triggering myogenesis (36).

Finally, in a previous paper, we showed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Trpc1 protein impaired myoblast differentiation (23). This was due to a default in of migration and in of alignment of myoblasts, which are important steps for myoblast fusion into myotubes. The default of alignment was also clearly observed in primary myoblasts derived from Trpc1−/− muscles primary culture (Fig. 6D), confirming the effect of the channel in cell migration. In regenerating muscles, we observed that MyoD and p27 expression was lower in Trpc1−/− than in Trpc1+/+ regenerating muscles. These two proteins seem to induce cell cycle arrest in response to cell-cell contact and to promote myoblast differentiation (38, 39). We therefore propose that the decreased expression of MyoD and p27 might be a consequence of the delayed alignment and cell-cell contacts of Trpc1−/− myoblasts.

In conclusion, this study shows that Trpc1 channels play a role in skeletal muscle development in vivo and in vitro by modulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway.

Acknowledgments

We warmly thank M. Van Schoor for excellent technical assistance. We also acknowledge Drs. J. Lebacq, L. Bertrand, and S. Horman for helpful discussions.

*

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Z01-101684 (to L. B.). This work was also supported by the “Association française contre les myopathies”, the “Association Belge contre les Maladies Neuro-musculaires”, by Grant ARC 10/15-029 from the General Direction of Scientific Research of the French Community of Belgium.

3

The abbreviations used are:

IGF

insulin-like growth factor

IRS

insulin receptor substrate(s)

TA

tibialis anterior

EDL

extensor digitorium longus

MHCd

developmental myosin heavy chain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weintraub H. (1993) The MyoD family and myogenesis: Redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell 75, 1241–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckingham M. (2001) Skeletal muscle formation in vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 440–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molkentin J. D., Olson E. N. (1996) Combinatorial control of muscle development by basic helix-loop-helix and MADS-box transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9366–9373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molkentin J. D., Black B. L., Martin J. F., Olson E. N. (1995) Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell 83, 1125–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halevy O., Novitch B. G., Spicer D. B., Skapek S. X., Rhee J., Hannon G. J., Beach D., Lassar A. B. (1995) Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science 267, 1018–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrés V., Walsh K. (1996) Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal, and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 132, 657–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergstrom D. A., Tapscott S. J. (2001) Molecular distinction between specification and differentiation in the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2404–2412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott M. O., Bober E., Lyons G., Arnold H., Buckingham M. (1991) Early expression of the myogenic regulatory gene, myf-5, in precursor cells of skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. Development 111, 1097–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sassoon D., Lyons G., Wright W. E., Lin V., Lassar A., Weintraub H., Buckingham M. (1989) Expression of two myogenic regulatory factors myogenin and MyoD1 during mouse embryogenesis. Nature 341, 303–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons G. E., Ontell M., Cox R., Sassoon D., Buckingham M. (1990) The expression of myosin genes in developing skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1465–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beylkin D. H., Allen D. L., Leinwand L. A. (2006) MyoD, Myf5, and the calcineurin pathway activate the developmental myosin heavy chain genes. Dev. Biol. 294, 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández A. M., Dupont J., Farrar R. P., Lee S., Stannard B., Le Roith D. (2002) Muscle-specific inactivation of the IGF-I receptor induces compensatory hyperplasia in skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florini J. R., Ewton D. Z., Coolican S. A. (1996) Growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocr. Rev. 17, 481–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musarò A., McCullagh K., Paul A., Houghton L., Dobrowolny G., Molinaro M., Barton E. R., Sweeney H. L., Rosenthal N. (2001) Localized Igf-1 transgene expression sustains hypertrophy and regeneration in senescent skeletal muscle. Nat. Genet. 27, 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeRoith D. (2000) Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling–overlapping or redundant pathways? Endocrinology 141, 1287–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitehead J. P., Clark S. F., Urso B., James D. E. (2000) Signaling through the insulin receptor. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan T. O., Rittenhouse S. E., Tsichlis P. N. (1999) AKT/PKB and other D3 phosphoinositide-regulated kinases: Kinase activation by phosphoinositide-dependent phosphorylation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 965–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alessi D. R., Cohen P. (1998) Mechanism of activation and function of protein kinase B. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alessi D. R., Downes C. P. (1998) The role of PI 3-kinase in insulin action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1436, 151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid A., Renaud J. F., Fosset M., Meaux J. P., Lazdunski M. (1984) The nitrendipine-sensitive Ca2+ channel in chick muscle cells and its appearance during myogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 11366–11372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Przybylski R. J., Szigeti V., Davidheiser S., Kirby A. C. (1994) Calcium regulation of skeletal myogenesis. II. Extracellular and cell surface effects. Cell Calcium 15, 132–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bijlenga P., Liu J. H., Espinos E., Haenggeli C. A., Fischer-Lougheed J., Bader C. R., Bernheim L. (2000) T-type α 1H Ca2+ channels are involved in Ca2+ signaling during terminal differentiation (fusion) of human myoblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7627–7632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis M., Zanou N., Van Schoor M., Gailly P. (2008) TRPC1 regulates skeletal myoblast migration and differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3951–3959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietrich A., Kalwa H., Storch U., Mederos y Schnitzler M., Salanova B., Pinkenburg O., Dubrovska G., Essin K., Gollasch M., Birnbaumer L., Gudermann T. (2007) Pressure-induced and store-operated cation influx in vascular smooth muscle cells is independent of TRPC1. Pflugers Arch. 455, 465–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maréchal G., Beckers-Bleukx G. (1993) Force-velocity relation and isomyosins in soleus muscles from two strains of mice (C57 and NMRI). Pflugers Arch. 424, 478–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks S. V., Faulkner J. A. (1988) Contractile properties of skeletal muscles from young, adult, and aged mice. J. Physiol. 404, 71–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanou N., Shapovalov G., Louis M., Tajeddine N., Gallo C., Van Schoor M., Anguish I., Cao M. L., Schakman O., Dietrich A., Lebacq J., Ruegg U., Roulet E., Birnbaumer L., Gailly P. (2010) Role of TRPC1 channel in skeletal muscle function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C149–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudnicki M. A., Schnegelsberg P. N., Stead R. H., Braun T., Arnold H. H., Jaenisch R. (1993) MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell 75, 1351–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tapscott S. J., Davis R. L., Lassar A. B., Weintraub H. (1990) MyoD: a regulatory gene of skeletal myogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 280, 3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schakman O., Kalista S., Bertrand L., Lause P., Verniers J., Ketelslegers J. M., Thissen J. P. (2008) Role of Akt/GSK-3beta/β-catenin transduction pathway in the muscle anti-atrophy action of insulin-like growth factor-I in glucocorticoid-treated rats. Endocrinology 149, 3900–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louis M., Van Beneden R., Dehoux M., Thissen J. P., Francaux M. (2004) Creatine increases IGF-I and myogenic regulatory factor mRNA in C2C12 cells. FEBS Lett. 557, 243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilson H., Schakman O., Combaret L., Lause P., Grobet L., Attaix D., Ketelslegers J. M., Thissen J. P. (2007) Myostatin gene deletion prevents glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. Endocrinology 148, 452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gailly P., Hermans E., Gillis J. M. (1996) Role of [Ca2+]i in “Ca2+ stores depletion Ca2+ entry coupling” in fibroblasts expressing the rat neurotensin receptor. J. Physiol. 491, 635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merritt J. E., Jacob R., Hallam T. J. (1989) Use of manganese to discriminate between calcium influx and mobilization from internal stores in stimulated human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 1522–1527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girgenrath M., Weng S., Kostek C. A., Browning B., Wang M., Brown S. A., Winkles J. A., Michaelson J. S., Allaire N., Schneider P., Scott M. L., Hsu Y. M., Yagita H., Flavell R. A., Miller J. B., Burkly L. C., Zheng T. S. (2006) TWEAK, via its receptor Fn14, is a novel regulator of mesenchymal progenitor cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. EMBO J. 25, 5826–5839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma R., Rundle D., Jacks J., Koch M., Downs T., Tsiokas L. (2003) Inhibitor of myogenic family, a novel suppressor of store-operated currents through an interaction with TRPC1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52763–52772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weintraub H., Davis R., Lockshon D., Lassar A. (1990) MyoD binds cooperatively to two sites in a target enhancer sequence: Occupancy of two sites is required for activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 5623–5627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vernon A. E., Philpott A. (2003) A single cdk inhibitor, p27Xic1, functions beyond cell cycle regulation to promote muscle differentiation in Xenopus. Development 130, 71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gavard J., Marthiens V., Monnet C., Lambert M., Mège R. M. (2004) N-cadherin activation substitutes for the cell contact control in cell cycle arrest and myogenic differentiation: Involvement of p120 and β-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36795–36802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodine S. C., Stitt T. N., Gonzalez M., Kline W. O., Stover G. L., Bauerlein R., Zlotchenko E., Scrimgeour A., Lawrence J. C., Glass D. J., Yancopoulos G. D. (2001) Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyabara E. H., Conte T. C., Silva M. T., Baptista I. L., Bueno C., Jr., Fiamoncini J., Lambertucci R. H., Serra C. S., Brum P. C., Pithon-Curi T., Curi R., Aoki M. S., Oliveira A. C., Moriscot A. S. (2010) Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 is involved in differentiation of regenerating myofibers in vivo. Muscle Nerve 42, 778–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glass D. J. (2010) PI3 kinase regulation of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 346, 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latres E., Amini A. R., Amini A. A., Griffiths J., Martin F. J., Wei Y., Lin H. C., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. (2005) Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) inversely regulates atrophy-induced genes via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2737–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson E. M., Tureckova J., Rotwein P. (2004) Permissive roles of phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase and Akt in skeletal myocyte maturation. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun L., Liu L., Yang X. J., Wu Z. (2004) Akt binds prohibitin 2 and relieves its repression of MyoD and muscle differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3021–3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson E. M., Hsieh M. M., Rotwein P. (2003) Autocrine growth factor signaling by insulin-like growth factor-II mediates MyoD-stimulated myocyte maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41109–41113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Small E. M., O'Rourke J. R., Moresi V., Sutherland L. B., McAnally J., Gerard R. D., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2010) Regulation of PI3-kinase/Akt signaling by muscle-enriched microRNA-486. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4218–4223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson E. M., Rotwein P. (2007) Selective control of skeletal muscle differentiation by Akt1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5106–5110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Q., Wu Z. (2000) The insulin-like growth factor-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt signaling pathway regulates myogenin expression in normal myogenic cells but not in rhabdomyosarcoma-derived RD cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36750–36757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson E. M., Rotwein P. (2006) Control of MyoD function during initiation of muscle differentiation by an autocrine signaling pathway activated by insulin-like growth factor-II. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29962–29971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]