Murine Anti-GD2 Monoclonal Antibody 3F8 Combined With Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor and 13-Cis-Retinoic Acid in High-Risk Patients With Stage 4 Neuroblastoma in First Remission (original) (raw)

Abstract

Purpose

Anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) combined with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) has shown efficacy against neuroblastoma (NB). Prognostic variables that could influence clinical outcome were explored.

Patients and Methods

One hundred sixty-nine children diagnosed with stage 4 NB (1988 to 2008) were enrolled onto consecutive anti-GD2 murine MoAb 3F8 ± GM-CSF ± 13-_cis_-retinoic acid (CRA) protocols after achieving first remission (complete remission/very good partial remission). Patients enrolled in regimen A (n = 43 high-risk [HR] patients) received 3F8 alone; regimen B (n = 41 HR patients), 3F8 + intravenous GM-CSF + CRA, after stem-cell transplantation (SCT); and regimen C (n = 85), 3F8 + subcutaneous GM-CSF + CRA, 46 of 85 after SCT, whereas 28 of 85 required additional induction therapy and were deemed ultra high risk (UHR). Marrow minimal residual disease (MRD) was measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Survival probability was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and prognostic variables were analyzed by multivariate Cox regression model.

Results

At 5 years from the start of immunotherapy, progression-free survival (PFS) improved from 44% for HR patients receiving regimen A to 56% and 62% for those receiving regimens B and C, respectively. Overall survival (OS) was 49%, 61%, and 81%, respectively. PFS and OS of UHR patients were 36% and 75%, respectively. Relapse was mostly at isolated sites. Independent adverse prognostic factors included UHR (PFS) and post–cycle two MRD (PFS and OS), whereas the prognostic factors for improved outcome were missing killer immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand (PFS and OS), human antimouse antibody response (OS), and regimen C (OS).

Conclusion

Retrospective analysis of consecutive trials from a single center demonstrated that MoAb 3F8 + GM-CSF + CRA is effective against chemotherapy-resistant marrow MRD. Its positive impact on long-term survival can only be confirmed definitively by randomized studies.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in supportive therapy and diagnostic precision in identifying risk groups, curing high-risk patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma (NB) presenting at age ≥ 18 months or with MYCN amplification has been daunting.1 Although multimodality induction can improve remission quality, the maintenance of long-term tumor control remains suboptimal. Myeloablative therapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation (SCT),2 differentiation therapy using 13-_cis_-retinoic acid (CRA),2 and immunotherapy using anti-GD2 antibody3 have shown efficacy in randomized trials. However, given the substantial acute and late toxicities after intensive chemoradiotherapy,4,5 it is imperative to identify treatments with fewer adverse effects.

From the first phase I study of murine anti-GD2 antibody6 to the most recent randomized proof of clinical benefit,3 cytokines have played key roles. In the Children's Oncology Group (COG) trial of anti-GD2 therapy, antibody ch14.18 was combined with two cytokines (ie, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF] and interleukin-2 [IL-2]).3 Yet most therapeutic antibodies, including rituximab, trastuzumab, and cetuximab, are effective without cytokines.7 Because cytokines are potentially toxic,3 their additional benefits when combined with antibodies need to be examined.

There are strong in vitro rationales for GM-CSF in 3F8-mediated and ch14.18-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) of NB.8–11 Myeloid activation markers on granulocytes (CD11a, CD63, CD87, and CD11b and its activation epitope CBRM1/5) increased after GM-CSF therapy in patients with metastatic NB.12 CBRM1/5 activation was associated with favorable patient outcome in a multivariable model. Moreover, CBRM1/5 activation was significantly higher after subcutaneous (SC) GM-CSF when compared with intravenous (IV) GM-CSF. In light of the effectiveness of 3F8 + GM-CSF against histologic and radiographic chemotherapy-resistant bone marrow disease,13 and the relatively mild toxicity profile of GM-CSF alone or in combination with 3F8,13 we evaluated survival and pattern of relapse among 169 high-risk patients whose first complete remission (CR)/very good partial remission (VGPR) was consolidated by 3F8 ± GM-CSF ± CRA in consecutive trials. Multivariate models were built to test for prognostic variables that could influence clinical outcome.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Characteristics

Patients characteristics are listed in Appendix Table A1 (online only). Patients received chemotherapy based on the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center or COG3973 induction, hyperfractionated 21-Gy local radiation, and surgical resection of the primary tumor,14 with or without second-line therapy to achieve remission,15 and with or without myeloablative therapy with stem-cell rescue.2,16 Once CR/VGPR was confirmed according to International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria,17 informed consent was obtained for treatment (Appendix Table A2, online only) according to institutional review board–approved protocols: regimen A (3F8 [1988 to 2000]; n = 43 high-risk [HR] patients),18 regimen B (addition of IV GM-CSF and oral CRA [1999 to 2003]; n = 41 HR patients),13 and regimen C (route of GM-CSF changed to SC [2003 to 2008]; n = 85 [57 HR and 28 ultra–high-risk (UHR) patients]). UHR patients had refractory disease, requiring additional cyclophosphamide ± topotecan or irinotecan15 after standard induction therapy to achieve CR/VGPR before enrollment for immunotherapy. GM-CSF was yeast-derived human recombinant protein (Sargramostim; Immunex, Seattle, WA). Only patients with stage 4 NB age 18 months to 12 years at diagnosis, or infants with stage 4 _MYCN_-amplified NB, were enrolled. Twenty-four of 43 patients receiving regimen A also received 131I-3F8 (20 mCi/kg) on the N7 protocol (Appendix Table A2, online only); their PFS and OS were no different from patients who did not receive 131I-3F8.

Treatment Regimens

Treatment regimens are summarized in Appendix Table A3 (online only). Dosing of GM-CSF for each patient was increased from 250 to 500 ug/m2 after the second day of 3F8, as long as the absolute neutrophil count was ≤ 20,000/μL. Treatment cycles were separated by 2- to 4-week rest periods through four cycles, then by 6- to 8-week rest periods through 24 months from study entry or until progressive disease (PD), whichever occurred earlier. For patients with elevated human antimouse antibody (HAMA) titer,19 treatment was deferred until their titers turned negative. After the second cycle of immunotherapy, oral CRA was initiated (used as described × six cycles2) between cycles of 3F8 + GM-CSF.

Disease Evaluation

Disease status was evaluated at enrollment and at least every 3 months, through 3 years from study entry. CR/VGPR were defined as the absence of disease by urinary catecholamines, metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, marrow histology, computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or bone scan.17 131I-MIBG (through November 1999) or 123I-MIBG scans were dosed as 1 mCi (37 MBq)/1.73 m2 and 10 mCi (370 MBq)/1.73 m2 body surface, respectively.

Marrow Assessment by Histology

Each examination consisted of two biopsies from bilateral anterior and posterior iliac crests and four aspirates from bilateral anterior and bilateral posterior iliac crests.20 Heparinized aspirate samples pooled from four sites were used for minimal residual disease (MRD) measurement.

MRD Detection by Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

MRD detection was carried out as previously described.21,22 The MRD marker panel included cyclin D1 (CCND1), ISL LIM homeobox 1 (ISL1), paired-like homeobox 2b (PHOX2B), and GD2 synthase (B4GALNT1). β2-microglobulin (β2M) was used as the endogenous control, and NB cell line NMB7 as the positive control. Each sample was quantified using the comparative CT method as fold difference relative to NMB7. All gene expression assays were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA): CCND1: Hs00277039_m1; ISL1: Hs00158126_m1; PHOX2B: Hs00243679_m1; B4GALNT1: Hs00155195_ m1; β2M: 4326319E. For each marker, positivity was defined as greater than upper limit of normal.22 All samples were run in duplicates. MRD was measured in marrow before treatment (pre-MRD) and after two cycles of 3F8 (post-MRD), at a median of 3.1 months from start of immunotherapy.

FCGR2A Polymorphism, Human Leukocyte Antigen, and Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor Genotyping

These were carried out as previously described.23–25 Allelic discrimination of FCGR2A was identified as [R/R] versus [H/H] versus [H/R]. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genotyping (2DL1, 2DL2, 2DL3, 3DL1, and 3DL2) was performed on DNA samples.24 Patients were considered as missing KIR ligand if they lacked any human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I ligand by HLA genotype for their inhibitory KIR identified by KIR genotype. Patients with all ligands present possessed all HLA class I ligands for their identified inhibitory KIR.25

Statistical Analysis

The clinical end points tested were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from start of 3F8 immunotherapy. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival probabilities, and log-rank test was used to test the univariate association between variables and PFS/OS. Multivariate Cox regression model was fitted with variables that had a univariate P value of less than .1 and the variable missing KIR ligand. Development of HAMA response was included as a time-dependent covariate using the hazard model λ(t|Z(t)) = λ0(t) exp(βZ(t)), where Z(t) = 1 for any time t after patient developed HAMA, and Z(t) = 0 otherwise; λ0(t) was the unknown baseline hazard, and exp(β) was the hazard ratio corresponding to the HAMA effect. Logistic regression was used to test the association between binary variables and treatment regimen. Time between diagnosis and start of immunotherapy was correlated with SCT using exact Wilcoxon rank sum test.

RESULTS

Survival After Anti-GD2 Antibody 3F8 Therapy in Children With HR Stage 4 NB

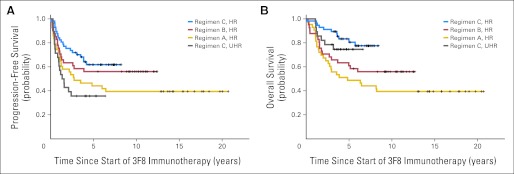

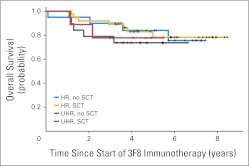

Survival is summarized in Table 1 and Figures 1A and 1B. All progression-free patients had at least 2.9 years of follow-up from the beginning of immunotherapy and at least 3.6 years from diagnosis. Among HR patients, 5-year PFS increased from 44% for those receiving regimen A (n = 43) to 56% and 62% for those receiving regimens B (n = 41) and C (n = 57), respectively. Four patients who died as a result of therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia or infection were scored as having PD. Similarly, 5-year OS improved from 49% to 61% and 81%, respectively. PFS and OS at 5 years for 28 UHR patients receiving regimen C were 36% and 75%, respectively. In univariate analysis, comparison of all four groups (regimens A, B, C [HR], and C [UHR]) found they were significantly different in PFS and OS (P = .018 and P = .003, respectively). Among those receiving regimen C, OS was similar for patients with or without SCT (Table 1; Appendix Fig A1 [online only]; P = .64). Patients undergoing SCT received immunotherapy after a longer median time from diagnosis compared with those who did not undergo SCT (8.8 v 5.8 months; P < .001). All three regimens were administered as outpatient treatment. Common adverse effects (during or shortly after 3F8 infusions) were grade 2 pain and grades 1 to 2 urticaria; SC GM-CSF occasionally caused local erythema. Toxicity profile was generally milder when compared with that of the published experience when both GM-CSF and IL-2 were used.3 There were no capillary leak syndromes or deaths resulting from toxicity during immunotherapy (Appendix Table A4, online only).

Table 1.

Survival Outcome at 5 Years After 3F8 Immunotherapy in Consecutive Regimens Among 169 Patients With HR* Stage 4 NB in First Remission

| Treatment Group | SCT | All Patients | Patients Receiving Regimen C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | PFS (%) | 95% CI | OS (%) | 95% CI | No. of Patients | PFS (%) | 95% CI | OS (%) | 95% CI | ||

| Regimen A (3F8 alone) | |||||||||||

| HR | — | 43 | 44 | 32 to 62 | 49 | 36 to 66 | |||||

| Regimen B (3F8 + IV GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||||

| HR | Yes | 41† | 56 | 43 to 74 | 61 | 48 to 78 | |||||

| Regimen C (3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||||

| HR | Yes | 57 | 62 | 50 to 76 | 81 | 70 to 92 | 37 | 69 | 55 to 86 | 78 | 65 to 95 |

| No | 20 | 50 | 32 to 78 | 84 | 69 to 100 | ||||||

| UHR‡ | Yes | 28 | 36 | 22 to 59 | 75 | 60 to 93 | 9 | 44 | 21 to 92 | 78 | 55 to 100 |

| No | 19 | 32 | 16 to 61 | 74 | 56 to 96 |

Fig 1.

(A) Progression-free survival (PFS) for 169 patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma in first remission after consecutive immunotherapy regimens: 3F8 alone (regimen A–high risk [HR]; n = 43), 3F8 + intravenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) + 13-_cis_-retinoic acid (CRA; regimen B-HR; n = 41), and 3F8 + subcutaneous GM-CSF + CRA (regimen C-HR; n = 57 and regimen C–ultra HR [UHR]; n = 28); P = .018 (derived from log-rank test to compare PFS among these four groups). (B) Overall survival (OS) among same cohort of patients; P = .003 (derived from log-rank test to compare OS among these four groups).

Frequency and Pattern of Relapse Among Treatment Groups

Relapse is summarized in Table 2. The median times to relapse or death from the start of immunotherapy were 2.7 years (regimen A [HR]), 1.5 years (regimen C [UHR]), and not reached (regimen B [HR] and regimen C [HR]). Most relapses were surprisingly focal or isolated. Isolated marrow/bone recurrences (22% to 29%) were defined as either only marrow or ≤ two MIBG-positive sites. CNS relapse was detected radiologically by CT and MRI and confirmed by biopsy or resection, being mostly isolated (regimen A, 30%; regimen B, 18%; regimen C, 21%). Patients with isolated soft tissue relapses detected by CT/MRI had no skeletal uptake by MIBG and no marrow disease by histology. In contrast to regimens A and B, it was noteworthy that the relapse pattern in regimen C changed to fewer multiple sites and more isolated soft tissues. Twenty-one patients (10 HR and 11 UHR) receiving regimen C were back in remission after experiencing relapse after surgery ± focal radiation ± short courses of chemotherapy and then re-treatment with 3F8-based immunotherapy. Eleven patients continued in second CR (range, 1.3 to 6.4 years), five had stable disease, and five had further PD. Of seven patients with isolated CNS relapse, six continued in second CR (median, 3.9 years), and one had both CNS and systemic relapses. All 21 patients remain alive, with median follow-up of 2.7 years since relapse.

Table 2.

Frequency and Pattern of Relapse and Time to Relapse Among Treatment Groups

| Treatment Group | Total Patients | PF Patients* | Patients Experiencing Relapse (%) | Pattern of Relapse | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sites | Isolated Marrow/Bone | Isolated CNS | Isolated Soft Tissue | ||||||||||

| No. | Median Time to Relapse or Death From Start of 3F8 (years) | No. | Median Follow-Up From Start of 3F8 (years) | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Regimen A (3F8 alone) | |||||||||||||

| HR | 43 | 2.7 | 20 | 15.5 | 53 | 9 | 39 | 5 | 22 | 7 | 30 | 2 | 9 |

| Regimen B (3F8 + IV GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||||||

| HR | 41 | NR | 24 | 10.2 | 41 | 8 | 47 | 5 | 29 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 6 |

| Regimen C (3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||||||

| HR | 57 | NR | 36 | 5.9 | 37 | 5 | 24 | 6 | 29 | 5 | 24 | 5 | 24 |

| UHR | 28 | 1.5 | 10 | 4.4 | 64 | 5 | 28 | 5 | 28 | 3 | 17 | 5 | 28 |

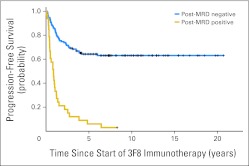

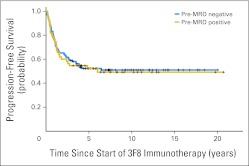

Post-MRD As Early Indicator of Treatment Responsiveness and Its Prognostic Significance

Because all patients were treated in CR/VGPR with negative marrow histology, subclinical disease could only be measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Pre-MRD was positive (regimen A, 24%; regimen B, 29%; regimen C, 37% [HR] and 43% [UHR]; Appendix Table A1, online only). Among patients receiving regimen C, pre-MRD was identical (39%) with or without SCT. When marrows were studied after two cycles of immunotherapy (post-MRD), before any exposure to CRA, MRD remission was achieved in 70% of patients with positive pre-MRD among those receiving regimen A, 83% among those receiving regimen B, and 76% [HR] and 67% [UHR] among those receiving regimen C (P = .79). Post-MRD was significantly associated with PFS and OS (both P < .001), whereas pre-MRD was not (P = .85 and P = .86, respectively; Appendix Table A1, online only). Kaplan-Meier PFS plots illustrated the strong association with post-MRD (Fig 2; P < .001) and lack of association with pre-MRD status (Appendix Fig A2, online only). Irrespective of regimen, both 5-year PFS and OS were markedly different between post-MRD–positive and –negative patients (Table 3).

Fig 2.

Strong association between minimal residual disease status after two cycles of 3F8 therapy (post-MRD) and progression-free survival for 169 high-risk patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma; P < .001.

Table 3.

Prognostic Impact of Pre- and Post-MRD on 5-Year Survival Outcome

| Treatment Group | MRD Marker Panel* | Pre-MRD | Post-MRD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS | OS | PFS | OS | ||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| Regimen A (3F8 alone) | |||||||||

| HR | Negative | 45 | 31 to 67 | 52 | 37 to 73 | 62 | 47 to 83 | 66 | 50 to 85 |

| Positive | 50 | 27 to 93 | 50 | 27 to 93 | 8 | 1 to 54 | 17 | 5 to 59 | |

| Regimen B (3F8 + IV GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||

| HR | Negative | 55 | 40 to 77 | 55 | 40 to 77 | 66 | 51 to 84 | 72 | 58 to 89 |

| Positive | 58 | 36 to 94 | 75 | 54 to 100 | 14 | 2 to 87 | 14 | 2 to 88 | |

| Regimen C (3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA) | |||||||||

| HR | Negative | 62 | 48 to 81 | 78 | 65 to 94 | 72 | 60 to 86 | 87 | 78 to 99 |

| Positive | 62 | 44 to 87 | 84 | 70 to 100 | NE† | 43 | 18 to 100 | ||

| UHR | Negative | 38 | 20 to 71 | 87 | 72 to 100 | 48 | 30 to 75 | 90 | 79 to 100 |

| Positive | 33 | 15 to 74 | 57 | 35 to 94 | NE† | 29 | 9 to 92 |

Univariate Analysis of Prognostic Factors

Risk factors for survival were tested in univariate analyses (Appendix Table A1, online only). Tumor and patient characteristics included sex, age, MYCN amplification, lactate dehydrogenase level, bone disease, marrow histology, FCGR2A polymorphism, and missing KIR ligand. Treatment variables included induction protocols, immunotherapy regimens, UHR, SCT, and CRA. Immunotherapy regimens (categorized as A [HR], B [HR], C [HR], and C [UHR]), SCT, post-MRD, and UHR were significantly associated with PFS. For OS, the statistically significant variables included immunotherapy regimen, post-MRD, and HAMA response. Induction protocols were found not to be prognostic for PFS or OS. CRA effect was not tested, because it was always administered with GM-CSF.

Multivariate Analysis of Prognostic Risk Factors

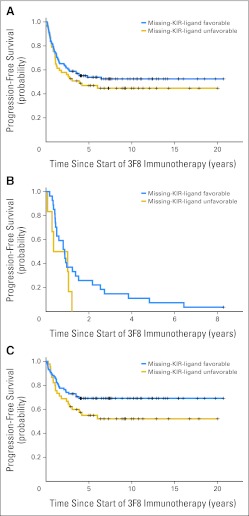

Variables with univariate P < .1 were included in the multivariate model (Table 4). Although missing KIR ligand was not significant in the univariate analysis, this variable was included, because its effect on PFS and OS was partly masked by the effect of post-MRD (Appendix Fig A3, online only). Regimens A and B were combined into a single category because there was no significant difference between their effectiveness in the multivariate models.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Variables on Survival Outcome Among 169 HR Patients With Stage 4 NB in First Remission Treated With 3F8 ± GM-CSF ± CRA

| Variable Tested | PFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Refractory to induction (UHR)* | 2.2 | 1.2 to 4.4 | .02 | — | — | —† |

| SCT consolidation before immunotherapy | 0.82 | 0.51 to 1.3 | .41 | — | — | — |

| Positive post-MRD | 6.52 | 3.9 to 10.8 | < .001 | 7.9 | 4.4 to 14.3 | < .001 |

| Missing KIR ligand | 0.62 | 0.38 to 1 | .05 | 0.55 | 0.31 to 0.99 | .045 |

| HAMA response‡ | — | — | — | 0.36 | 0.21 to 0.64 | < .001 |

| Addition of SC GM-CSF + CRA (regimen C) | 0.85 | 0.49 to 1.6 | .58 | 0.52 | 0.29 to 0.92 | .026 |

Positive post-MRD (measure of lack of responsiveness to immunotherapy) was an independent adverse prognostic factor for PFS and OS, whereas UHR (measure of refractoriness to induction) was independently prognostic for adverse PFS. In contrast, missing KIR ligand had a favorable influence on PFS and OS. For OS, having HAMA response and the addition of SC GM-CSF in regimen C versus no GM-CSF (regimen A) or IV GM-CSF (regimen B) had an independent positive impact. However, definitive proof of efficacy contributed by regimen C will require randomized comparisons.

To address the potential confounding factors on survival after relapse, we categorized the postrelapse therapies received as follows: one, high-dose cyclophosphamide-based therapy14,15,26 ± SCT27; two, irinotecan + temozolomide28; three, local control by radiation ± intrathecal 131I-8H929 ± surgical resection; and four, re-treatment with 3F8-based immunotherapy (Appendix Table A5, online only). When survival was calculated from the time of relapse, each of the four salvage modalities was significant in univariate analysis, with P ≤ .01. We also included time from diagnosis to relapse (< 18 v ≥ 18 months; P = .02 for association with postrelapse survival), previously shown to be a highly significant prognostic variable for survival after NB progression30 in a multivariable model (Appendix Table A6, online only). In addition to the statistical impact of time to relapse on OS, regimen C received before relapse remained significant after adjusting for other variables. Postrelapse therapies, including high-dose cyclophosphamide-based therapy and re-treatment with 3F8, were also found to have a positive impact on survival. However, these findings can only be confirmed by randomized studies.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective analysis of consecutive immunotherapy regimens reflected the clinical experience spanning 20 years by a single institution using anti-GD2 antibody 3F8 in the treatment of patients with high-risk stage 4 NB in their first CR/VGPR. Even though 3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA (regimen C) was identified as being independently prognostic for patient survival, the definitive test of efficacy would require a randomized trial, because there might have been unmeasured confounding factors during preimmunotherapy treatments or postrelapse therapies. Our analysis, nevertheless, did suggest an improvement in OS over time, in part because of the effective anti-NB activity of regimen C. The effects of GM-CSF and CRA cannot be separated, because they were always administered together. However, use of the SC route of administration of GM-CSF instead of the IV route seemed to provide maximal benefit. Nevertheless, by compressing 10 days of treatment (regimen B) into 5 days (regimen C), the advantage of SC GM-CSF could be confounded by higher 3F8 serum levels. Because approximately 80% of de novo patients achieved CR/VGPR and therefore qualified for immunotherapy,14 overall cure rate is still suboptimal. Although no patient in our cohorts suffered major organ toxicity or died as a result of immunotherapy, toxicity profile of antibody alone, versus its combination with IL-2 or GM-CSF, will require randomized comparisons.

NB recurrence among patients with stage 4 disease reported in the literature has generally involved multiple sites.31,32 Focal relapses were uncommon (< 10%).32,33 In contrast, a majority of relapses in the present analysis were isolated (CNS, marrow/bone, or soft tissue). CNS disease is uncommon at diagnosis and was relatively rare before the era of immunotherapy.34,35 It is striking that CNS relapse after immunotherapy was mostly focal without evidence of systemic disease. Despite effective systemic chemotherapy,3,14 given the inability of 3F8 to cross the blood-brain barrier, eventual CNS relapse seems unavoidable. Isolated CNS relapse could be indirect evidence for the effectiveness of 3F8 for systemic disease. Such CNS relapses were previously reported among patients with _HER2_-amplified breast cancer after trastuzumab therapy.36 CNS spread is generally followed by further recurrence along the craniospinal axis, with or without systemic relapse. In our study, six of seven such patients were back in remission after salvage protocol employing intrathecal radiolabeled antibodies.29

Responsiveness to induction chemotherapy is well known to be prognostic for patient outcome.37–39 Necessity of second-line therapy to achieve CR/VGPR to qualify for immunotherapy (UHR) foreshadowed a more aggressive tumor, reflected by its being an independent adverse predictor of PFS. As for SCT, it was found not to be independently prognostic for outcome (Table 4), with comparable survival plot for patients receiving regimen C with or without SCT (Appendix Fig A1, online only). The most common reason for not receiving SCT was parental concern over transplantation toxicity; no known disease-related factors were used in the decision. In using immunotherapy, SCT may not have had the same benefit as that demonstrated in the earlier protocols, where induction therapy was less intensive.2 Omission of high-dose consolidation therapy might spare many patients unnecessary treatment toxicities.

Curability of high-risk patients with stage 4 NB remained less than 40% despite intensive therapies that included SCT for MRD.2,40,41 Using a marker panel derived from genome-wide search,22 abnormal levels of tumor transcripts were detected in 24% to 43% of patients before immunotherapy. The level of pre-MRD was least favorable among patients receiving 3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA (regimen C) and best among the 3F8-alone group (regimen A; Appendix Table A1, online only). After two cycles of immunotherapy, 67% to 83% of patients achieved MRD remission. In contrast to pre-MRD, positive post-MRD was an independent adverse predictor of PFS and OS (Table 4). This early indicator of immunotherapy resistance was akin to the observation of early MRD in leukemia as an indicator of induction resistance.42,43

Previous studies have implicated high-affinity Fc receptor for human44,45 and mouse immunoglobulin G23 as well as the adhesion molecule CD11b in improving patient survival.12 Unlike in patients with primary refractory NB,46 FCGR2A polymorphism did not reach significance in this cohort of patients treated in first remission. On the other hand, although missing KIR ligand was not significant in the univariate model, when added to the multivariate model, it achieved statistical significance after adjusting for the effect of post-MRD. Missing KIR ligand was previously shown to be prognostic for survival after treatment with 3F8-based immunotherapy.25,47 Ability of unlicensed natural killer (NK) cells to kill NB efficiently in the presence of 3F8 despite HLA upregulation could be an explanation.48,49 Similar effects of missing KIR ligand in NB were found in autotransplantation50 and more recently with hu14.18–IL-2.51

The favorable impact of developing HAMA response against mouse antibody, although counterintuitive, confirmed a previous observation of HAMA as a surrogate marker of an anti-idiotype network in prolonging the antitumor effect.52 However, the potential importance of a host immune response for long-term NB control has not been extensively explored. Furthermore, although marrow MRD is useful for quantifying NB responsiveness to myeloid ADCC, other MRD measurements are likely to be necessary for detecting NB sensitivity to NK-mediated ADCC. Given the potential benefit of myeloid and NK cells in antibody-based treatment of metastatic NB, further optimization of their effector functions should be considered.

Acknowledgment

We thank the neuroblastoma research nurses and nurse practitioners, pediatric attending physicians and hematology/oncology fellows, and the Departments of Medicine, Pathology, Pediatric Surgery, Pediatric Radiology, and Radiation Oncology of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center for their expertise in caring for our patients enrolled onto these clinical trials. We also thank the neuroblastoma research laboratory for performing correlative biologic studies and the neuroblastoma data management team for data collection.

Appendix

Fig A1.

Overall survival among patients treated with regimen C, stratified according high-risk (HR; with or without stem-cell transplantation [SCT]) and ultra-HR (UHR; with or without SCT) status; P = .64.

Fig A2.

Absence of association between minimal residual disease status before therapy (pre-MRD) and progression-free survival among 169 high-risk patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma.

Fig A3.

Prognostic importance of missing killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand among (A) all patients, (B) those with positive minimal residual disease status after two cycles of 3F8 therapy (post-MRD; P = .16), and (C) those with negative post-MRD (P = .1).

Table A1.

Patient Characteristics, Treatment Variables, and Prognostic Factors by Regimen

| Variable | Regimen A 3F8 (HR) | Regimen B 3F8 + IV GMCSF (HR) | Regimen C | P* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3F8 + SC GMCSF (HR) | 3F8 + SC GMCSF (UHR) | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | PFS | OS |

| Immunotherapy regimen | |||||||||

| No. of patients | 43 | 41 | 57 | 28 | |||||

| Relapse or death | 26 | 18 | 21 | 18 | |||||

| Death | 26 | 18 | 11 | 7 | |||||

| Sex | .55 | .56 | |||||||

| Male | 25 | 58 | 26 | 63 | 39 | 68 | 12 | 43 | |

| Female | 18 | 42 | 15 | 37 | 18 | 32 | 16 | 57 | |

| Age, months | .5 | .65 | |||||||

| ≥ 18 | 41 | 95 | 38 | 93 | 52 | 91 | 27 | 96 | |

| < 18 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 4 | |

| MYCN | .59 | .29 | |||||||

| Amplified | 15 | 35 | 14 | 34 | 29 | 51 | 7 | 25 | |

| Not amplified | 28 | 65 | 27 | 66 | 28 | 49 | 21 | 75 | |

| LDH, U/mL | .84 | .64 | |||||||

| > 1,500 | 14 | 33 | 15 | 37 | 18 | 32 | 4 | 14 | |

| < 1,500 | 28 | 65 | 18 | 44 | 28 | 49 | 16 | 57 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 11 | 19 | 8 | 29 | |

| Bone | .45 | .25 | |||||||

| Yes | 32 | 74 | 31 | 76 | 42 | 74 | 17 | 61 | |

| No | 11 | 26 | 10 | 24 | 15 | 26 | 11 | 39 | |

| Bone marrow | .48 | .22 | |||||||

| Yes | 39 | 91 | 33 | 80 | 50 | 88 | 23 | 82 | |

| No | 4 | 9 | 8 | 20 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 18 | |

| SCT | .014 | .19 | |||||||

| Yes | 1 | 2 | 41 | 100 | 37 | 65 | 9 | 32 | |

| No | 42 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 35 | 19 | 68 | |

| FCGR2A polymorphism† | .8 | .54 | |||||||

| H/H | 14 | 33 | 10 | 24 | 13 | 23 | 10 | 36 | |

| H/R or R/R | 29 | 67 | 31 | 76 | 44 | 77 | 18 | 64 | |

| Missing KIR ligand | .37 | .32 | |||||||

| Favorable | 31 | 72 | 23 | 56 | 38 | 67 | 20 | 71 | |

| Unfavorable | 12 | 28 | 18 | 44 | 19 | 33 | 8 | 29 | |

| Pre-MRD | .85 | .86 | |||||||

| Positive | 10 | 24 | 12 | 29 | 21 | 37 | 12 | 43 | |

| Negative | 31 | 76 | 29 | 71 | 36 | 63 | 16 | 57 | |

| Post-MRD | < .001 | < .001 | |||||||

| Positive | 12 | 29 | 7 | 18 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 25 | |

| Negative | 29 | 71 | 32 | 82 | 48 | 87 | 21 | 75 | |

| UHR‡ | .02 | .46 | |||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 100 | |

| No | 43 | 100 | 41 | 100 | 57 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| HAMA response§ | .12 | .006 | |||||||

| Yes | 24 | 56 | 29 | 71 | 46 | 80 | 21 | 75 | |

| No | 19 | 44 | 12 | 29 | 11 | 20 | 7 | 25 | |

| Median time to first positive HAMA, months | 19.3 | 5.3 | 9.9 | 9.1 | |||||

| Median time to HAMA turning negative, months | 3.97 | 4.62 | 5.71 | 3.09 | |||||

| Induction protocol∥ | .84 | .91 | |||||||

| I. MSKCC-COG3973 regimen¶ | 43 | 100 | 28 | 69 | 50 | 87 | 22 | 78 | |

| II. Intensive but non–MSKCC-COG3973 regimen | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 11 | |

| III. Less intensive regimen | 0 | 0 | 10 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 11 | |

| CRA | |||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 14 | 37 | 90 | 53 | 93 | 28 | 100 | |

| No | 37 | 86 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

Table A2.

Protocols and Treatments for HR Patients With Stage 4 NB at MSKCC

| Immunotherapy Group | Before Immunotherapy | CRA | No. of Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSKCC Protocol Name | ClinicalTrials.gov | Consolidation | |||

| Regimen A (3F8 alone) | N6 | NCI-V90-0023 | None | None | 19 |

| N7 | NCT00002634 | 131I-3F8 | None | 24 | |

| Regimen B (3F8 + IV GM-CSF + CRA) | 94-018 | NCT00002560 | SCT | Yes | 41* |

| Regimen C (3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA) | 03-077 | NCT00072358 | None | Yes | 39 |

| 03-077 | NCT00072358 | SCT | Yes | 46 |

Table A3.

Roadmap of 3F8 Immunotherapy at MSKCC

| Treatment Day | Day of Week* | Regimen A: 3F8 Alone, 3F8 (mg/m2) | Regimen B | Regimen C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3F8 + IV GM-CSF + CRA† | 3F8 + SC GM-CSF + CRA | |||||

| GM-CSF (ug/m2) | 3F8 (mg/m2) | GM-CSF (ug/m2) | 3F8 (mg/m2) | |||

| −5 | Wed | 250 SC | 250 SC | |||

| −4 | Thurs | 250 SC | 250 SC | |||

| −3 | Fri | 250 SC | 250 SC | |||

| −2 | Sat | 250 SC | 250 SC | |||

| −1 | Sun | 250 SC | 250 SC | |||

| 0 | Mon | 10 | 250 IV | 10 | 250 SC | 20 |

| 1 | Tues | 10 | 250 IV | 10 | 250 SC | 20 |

| 2 | Wed | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | 500 SC | 20 |

| 3 | Thurs | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | 500 SC | 20 |

| 4 | Fri | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | 500 SC | 20 |

| 5 | Sat | 500 SC | ||||

| 6 | Sun | 500 SC | ||||

| 7 | Mon | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | ||

| 8 | Tues | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | ||

| 9 | Wed | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | ||

| 10 | Thurs | 10 | 500 IV | 10 | ||

| 11 | Fri | 10 | 500 IV | 10 |

Table A4.

Comparison of Toxicity Profile (grade 3 or 4)

| Toxicity | Regimen A (n = 24; %)* 3F8 Alone | Regimen B (n = 41; %) 3F8 + IV GM-CSF | Regimen C (n = 85; %) 3F8 + SC GM-CSF | NCT00026312 (COG phase III; n = 137; %)† ch14.18 + GM-CSF + IL-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain‡ | 0 | 2 | 1 | 52 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 2 | 0 | 18 |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 5 | 3§ | 13 |

| Fever without neutropenia | 0 | 12 | 5 | 39 |

| Acute capillary leak syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction∥ | 0 | 0 | 4 | 25 |

| Urticaria∥ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Infection | 4 | 5 | 14 | 39 |

| Catheter-related infection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Nausea | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 |

| Hyponatremia | 29 | 7 | 0 | 23 |

| Hypokalemia | 29 | 12 | 11 | 35 |

| Abnormal ALT | 17 | 7 | 8 | 23 |

| Abnormal AST | 8 | 0 | 4 | 10 |

| Hypercalcemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Serum sickness∥ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Seizure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CNS cortical syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 5 | 2 | —¶ |

Table A5.

Postrelapse Treatment Modalities and Time to Relapse by Regimen

| Treatment Modality at Relapse* | Regimen A | Regimen B | Regimen C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3F8 Alone (HR; n = 22) | 3F8 + IV GM-CSF (HR; n = 17) | 3F8 + SC GM-CSF (HR; n = 21) | 3F8 + SC GM-CSF (UHR; n = 18) | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| I. High-dose therapy | ||||||||

| Administered | 13 | 59 | 5 | 29 | 10 | 48 | 9 | 50 |

| Not administered | 9 | 41 | 12 | 71 | 11 | 52 | 9 | 50 |

| II. Irinotecan + temozolomide | ||||||||

| Administered | 1 | 5 | 3 | 18 | 9 | 43 | 14 | 78 |

| Not administered | 21 | 95 | 14 | 82 | 12 | 57 | 4 | 22 |

| III. Local XRT ± surgery | ||||||||

| Administered | 14 | 64 | 7 | 41 | 15 | 71 | 15 | 83 |

| Not administered | 8 | 36 | 10 | 59 | 6 | 29 | 3 | 17 |

| IV. Re-treatment with 3F8 | ||||||||

| Administered | 7 | 32 | 3 | 18 | 9 | 43 | 8 | 44 |

| Not administered | 15 | 68 | 14 | 82 | 12 | 57 | 10 | 56 |

| Time to relapse, months† | ||||||||

| < 18 | 10 | 45 | 6 | 35 | 7 | 33 | 9 | 50 |

| ≥ 18 | 12 | 55 | 11 | 65 | 14 | 67 | 9 | 50 |

Table A6.

OS After Relapse: Multivariable Model

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to relapse, months* | |||

| < 18 | Reference | — | |

| ≥ 18 | 0.38 | 0.21 to 0.67 | .001 |

| Regimen before relapse | |||

| A/B | Reference | — | |

| C | 0.23 | 0.11 to 0.46 | < .001 |

| Treatment modality at relapse (administered v not administered)† | |||

| I. High-dose therapy | 0.48 | 0.26 to 0.88 | .018 |

| II. Irinotecan + temozolomide | 0.60 | 0.30 to 1.19 | .143 |

| III. Local XRT ± surgery | 0.74 | 0.40 to 1.38 | .350 |

| IV. Re-treatment with 3F8 | 0.29 | 0.14 to 0.59 | .001 |

Footnotes

Supported in part by Grants No. CA106450, CA118845, and CA72868 from the National Institutes of Health; by Hope Street Kids; by the Justin Zahn Fund; by the Katie's Find A Cure Fund; and by the Robert Steel Foundation.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Nai-Kong V. Cheung

Provision of study materials or patients: Nai-Kong V. Cheung, Brian H. Kushner, Kim Kramer, Shakeel Modak

Collection and assembly of data: Nai-Kong V. Cheung, Irene Y. Cheung, Brian H. Kushner, Elizabeth Chamberlain, Kim Kramer, Shakeel Modak

Data analysis and interpretation: Nai-Kong V. Cheung, Irene Y. Cheung, Irina Ostrovnaya

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long-term results for children with high-risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: A Children's Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laverdière C, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Long-term outcomes in survivors of neuroblastoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobbie WL, Moshang T, Carlson CA, et al. Late effects in survivors of tandem peripheral blood stem cell transplant for high-risk neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:679–683. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung NK, Lazarus H, Miraldi FD, et al. Ganglioside GD2 specific monoclonal antibody 3F8: A phase I study in patients with neuroblastoma and malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1430–1440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.9.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillman RO. Cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2011;26:1–64. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modak S, Cheung NK. Disialoganglioside directed immunotherapy of neuroblastoma. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:67–77. doi: 10.1080/07357900601130763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker E, Mueller BM, Handgretinger R, et al. Effect of a chimeric anti-ganglioside GD2 antibody on cell-mediated lysis of human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metelitsa LS, Gillies SD, Super M, et al. Antidisialoganglioside/granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor fusion protein facilitates neutrophil antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and depends on FcgammaRII (CD32) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) for enhanced effector cell adhesion and azurophil granule exocytosis. Blood. 2002;99:4166–4173. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batova A, Kamps A, Gillies SD, et al. The ch14.18-GM-CSF fusion protein is effective at mediating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4259–4263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung IY, Hsu K, Cheung NK. Activation of peripheral-blood granulocytes is strongly correlated with patient outcome after immunotherapy with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:426–432. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Cheung NK. Phase II trial of the anti-G(D2) monoclonal antibody 3F8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4189–4194. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.22.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushner BH, Kramer K, LaQuaglia MP, et al. Reduction from seven to five cycles of intensive induction chemotherapy in children with high-risk neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4888–4892. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, et al. Camptothecin analogs (irinotecan or topotecan) plus high-dose cyclophosphamide as preparative regimens for antibody-based immunotherapy in resistant neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:84–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kushner BH, Cheung NK, Kramer K, et al. Topotecan combined with myeloablative doses of thiotepa and carboplatin for neuroblastoma, brain tumors, and other poor-risk solid tumors in children and young adults. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:551–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung NK, Kushner BH, Cheung IY, et al. Anti-G(D2) antibody treatment of minimal residual stage 4 neuroblastoma diagnosed at more than 1 year of age. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3053–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung NK, Cheung IY, Canete A, et al. Antibody response to murine anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies: Correlation with patient survival. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2228–2233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung NK, Heller G, Kushner BH, et al. Detection of metastatic neuroblastoma in bone marrow: When is routine marrow histology insensitive? J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2807–2817. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung IY, Lo Piccolo MS, Kushner BH, et al. Early molecular response of marrow disease to biologic therapy is highly prognostic in neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3853–3858. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung IY, Feng Y, Gerald W, et al. Exploiting gene expression profiling to identify novel minimal residual disease markers of neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7020–7027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung NK, Sowers R, Vickers AJ, et al. FCGR2A polymorphism is correlated with clinical outcome after immunotherapy of neuroblastoma with anti-GD2 antibody and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2885–2890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu KC, Liu XR, Selvakumar A, et al. Killer Ig-like receptor haplotype analysis by gene content: Evidence for genomic diversity with a minimum of six basic framework haplotypes, each with multiple subsets. J Immunol. 2002;169:5118–5129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venstrom JM, Zheng J, Noor N, et al. KIR and HLA genotypes are associated with disease progression and survival following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7330–7334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kushner BH, Cheung IY, Kramer K, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide inhibition of humoral immune response to murine monoclonal antibody 3F8 in neuroblastoma patients: Broad implications for immunotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:430–434. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, et al. Topotecan, thiotepa, and carboplatin for neuroblastoma: Failure to prevent relapse in the central nervous system. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:271–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, et al. Irinotecan plus temozolomide for relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5271–5276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer K, Kushner BH, Modak S, et al. Compartmental intrathecal radioimmunotherapy: Results for treatment for metastatic CNS neuroblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:409–418. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.London WB, Castel V, Monclair T, et al. Clinical and biologic features predictive of survival after relapse of neuroblastoma: A report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3286–3292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrella T, Quirt I, Verma S, et al. Single-agent interleukin-2 in the treatment of metastatic melanoma: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:484–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George RE, Li S, Medeiros-Nancarrow C, et al. High-risk neuroblastoma treated with tandem autologous peripheral-blood stem cell-supported transplantation: Long-term survival update. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2891–2896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthay KK, Atkinson JB, Stram DO, et al. Patterns of relapse after autologous purged bone marrow transplantation for neuroblastoma: A Children's Cancer Group pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:2226–2233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthay KK, Brisse H, Couanet D, et al. Central nervous system metastases in neuroblastoma: Radiologic, clinical, and biologic features in 23 patients. Cancer. 2003;98:155–165. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer K, Kushner B, Heller G, et al. Neuroblastoma metastatic to the central nervous system: The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience and a literature review. Cancer. 2001;91:1510–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musolino A, Ciccolallo L, Panebianco M, et al. Multifactorial central nervous system recurrence susceptibility in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer: Epidemiological and clinical data from a population-based cancer registry study. Cancer. 2011;117:1837–1846. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthay KK, Edeline V, Lumbroso J, et al. Correlation of early metastatic response by 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy with overall response and event-free survival in stage IV neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2486–2491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt M, Simon T, Hero B, et al. The prognostic impact of functional imaging with (123)I-mIBG in patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma > 1 year of age on a high-risk treatment protocol: Results of the German Neuroblastoma Trial NB97. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1552–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katzenstein HM, Cohn SL, Shore RM, et al. Scintigraphic response by 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scan correlates with event-free survival in high-risk neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3909–3915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson AD, Pinkerton CR, Lewis IJ, et al. High-dose rapid and standard induction chemotherapy for patients aged over 1 year with stage 4 neuroblastoma: A randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:247–256. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Hartman O, et al. 28 years of high-dose therapy and SCT for neuroblastoma in Europe: Lessons from more than 4000 procedures. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(suppl 2):S118–S127. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: A Children's Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marin D, Ibrahim AR, Lucas C, et al. Assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:232–238. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weng WK, Levy R. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3940–3947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1789–1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kushner B, Kramer K, Modak S, et al. Anti-GD2 anitbody 3F8 plus granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for primary refractory neuroblastoma (NB) in the bone marrow (BM) Proc Amer Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:526s. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venstrom JM, Zheng J, Kushner B, et al. NK cell killer Ig-like receptor (KIR) genotype as a novel biomarker for neuroblastoma patients receiving anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 3F8. 101st Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; April 17-21, 2010; Washington, DC. abstr 5586. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho D, Shook DR, Shimasaki N, et al. Cytotoxicity of activated natural killer cells against pediatric solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3901–3909. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarek N, Gallagher MM, Zheng J, et al. Unlicensed natural killer cells dominate neuroblastoma killing in the presence of anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody. J Clin Invest. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leung W, Handgretinger R, Iyengar R, et al. Inhibitory KIR-HLA receptor-ligand mismatch in autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for solid tumour and lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:539–542. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delgado DC, Hank JA, Kolesar J, et al. Genotypes of NK cell KIR receptors, their ligands, and Fcgamma receptors in the response of neuroblastoma patients to Hu14.18-IL2 immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9554–9561. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheung NK, Guo HF, Heller G, et al. Induction of Ab3 and Ab3′ antibody was associated with long-term survival after anti-G(D2) antibody therapy of stage 4 neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2653–2660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]