Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus requires glycosylated wall teichoic acids (original) (raw)

Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan (PG) is densely functionalized with anionic polymers called wall teichoic acids (WTAs). These polymers contain three tailoring modifications: d-alanylation, α-_O_-GlcNAcylation, and β-_O_-GlcNAcylation. Here we describe the discovery and biochemical characterization of a unique glycosyltransferase, TarS, that attaches β-_O_-GlcNAc (β-_O_-N_-acetyl-d-glucosamine) residues to S. aureus WTAs. We report that methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is sensitized to β-lactams upon tarS deletion. Unlike strains completely lacking WTAs, which are also sensitive to β-lactams, Δ_tarS strains have no growth or cell division defects. Because neither α-_O_-GlcNAc nor β-_O_-Glucose modifications can confer resistance, the resistance phenotype requires a highly specific chemical modification of the WTA backbone, β-_O_-GlcNAc residues. These data suggest β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs scaffold factors required for MRSA resistance. The β-_O_-GlcNAc transferase identified here, TarS, is a unique target for antimicrobials that sensitize MRSA to β-lactams.

Keywords: PBP2A, antibiotic resistance, beta lactam potentiation, murein, WTA glycosylation

Peptidoglycan (PG), a cross-linked polymeric matrix that surrounds bacterial cells, is essential for survival (1). It is a major target for clinically used antibiotics, including the β-lactams (2). Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is responsible for a large percentage of β-lactam–resistant infections and there is an ongoing need for new strategies to treat these infections (3). Resistance in MRSA involves the acquired gene, mecA, which encodes PBP2a, a transpeptidase that functions to cross-link peptidoglycan strands when native transpeptidases are inactivated by β-lactams (4–6). Many other genes native to S. aureus must be present for _mecA_-mediated resistance to operate (7–10). Understanding how different factors participate in β-lactam resistance is of paramount importance for developing new approaches to combat MRSA.

Preventing wall teichoic acid (WTA) synthesis by blocking TarO, which catalyzes the first step in the WTA pathway, sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams (11, 12). S. aureus WTAs are covalently attached to PG and consist of a poly(ribitol phosphate) [poly(RboP)] backbone containing three tailoring modifications: d-alanylation, α-_O_-GlcNAcylation, and β-_O_-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 1) (13, 14). WTAs have been implicated in cell shape, cell division, biofilm formation, phage infectivity, and pathogenesis, and evidence suggests that the tailoring modifications contribute to these functions (13, 14). For example, d-alanylation promotes biofilm formation, increases resistance to cationic antibiotics, and plays a role in virulence, whereas _O_-GlcNAcylation is required for infection by serogroups A, B, and F phages of S. aureus (13–18).

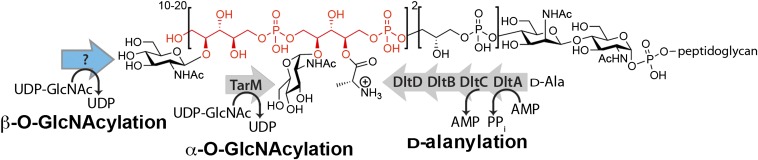

Fig. 1.

Wall teichoic acids in S. aureus contain three different types of tailoring modifications. S. aureus WTAs are composed of ribitol-phosphate repeats (two repeats are shown in red) tailored with d-alanines, α-_O_-GlcNAcs, and β-_O_-GlcNAcs. Enzymes responsible for α-_O_-GlcNAcylation and d-alanylation were previously identified. The enzyme (blue arrow) that attaches β-_O_-GlcNAcs to poly(RboP)-WTA was unidentified before this work.

We sought to determine whether the WTA polymer itself or a backbone modification regulates various WTA functions in S. aureus. Our studies required knowing the genes that encode the tailoring enzymes. The genes involved in d-alanylation and α-_O_-GlcNAcylation were previously identified, but the gene encoding the transferase that attaches β-_O_-GlcNAc residues to WTAs was not (19–23). Here we report the identification of this unique gene, tarS, and we profile the substrate preferences of the encoded β-O_-GlcNAc transferase. We show that the WTA backbone is required for proper cell division, whereas β-O_-GlcNAcylation is required to maintain β-lactam resistance in MRSA. Unlike Δ_tarO MRSA strains, which are also β-lactam sensitive, Δ_tarS strains have no morphological or cell division defects. Hence, the β-lactam susceptibility is not coupled to the global defects in cell division that occur in the absence of WTAs. Through genetic manipulations of WTA tailoring enzymes, we demonstrate that the proper stereochemical linkage of the sugar to the WTA backbone and the C2 _N_-acetyl substituent are required for the resistant phenotype. Because the structural features required are specific, we speculate that β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs interact with cell surface factors necessary for β-lactam resistance. We conclude that TarS is a unique possible target for inhibitors to be used in combination with β-lactams to overcome MRSA infections.

Results

Identification of a β-O-GlcNAc Transferase in S. aureus.

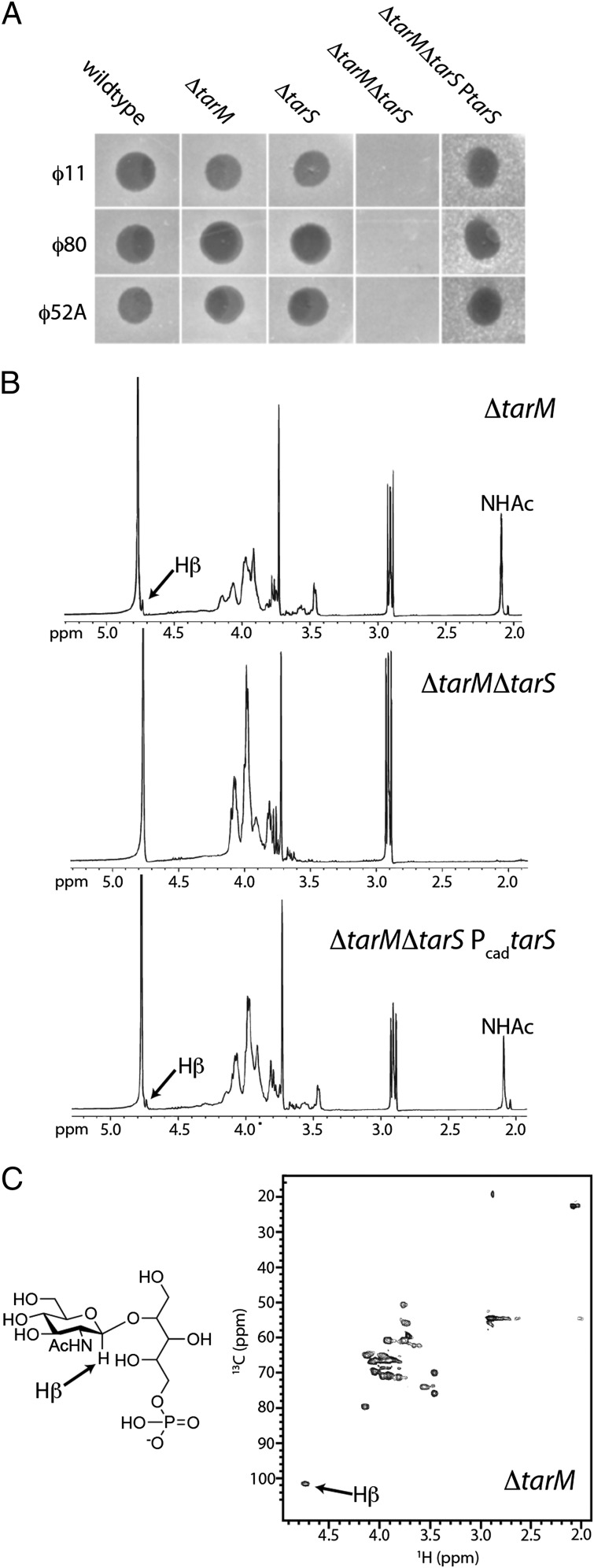

We recently identified a phage-resistant S. aureus strain, K6, which produces nonglycosylated WTAs (21). This strain carried a transposon in the tarM gene, and the encoded TarM protein was identified as a WTA α-O_-GlcNAc transferase. We subsequently found that a targeted tarM deletion strain, RN4220Δ_tarM, is still susceptible to S. aureus serogroup B phages ϕ11, ϕ52A, and ϕ80 (Fig. 2_A_). Because phage infection depends on WTA glycoepitopes (18), these data suggested that WTAs are glycosylated in the RN4220Δ_tarM_ strain. NMR analysis of WTAs from the Δ_tarM_ strain showed a WTA structure consistent with β-_O_-GlcNAcylated ribitol phosphate (Fig. 2 B and C) (24). Thus, S. aureus strain RN4220 contains a β-_O_-GlcNAc transferase in addition to the previously identified α-_O_-GlcNAc transferase.

Fig. 2.

TarS is a β-O_-GlcNAc-WTA transferase in vivo. (A) Soft agar assay for phage susceptibility of RN4220 wild type, Δ_tarM, Δ_tarS_, Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_, and the double mutant complemented with tarS (Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_P_tarS_). The double mutant, Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS,_ leads to resistance to serogroup B phages ϕ52A, ϕ11, and ϕ80. Mutation 201A, leading to a truncated tarS gene, was identified in the previously reported strain K6. This explains previous findings (21) that this strain, which contains a transposon insertion in tarM, is completely phage resistant. (B) 1H NMR spectra of chemically extracted and degraded WTA monomers from the RN4220 Δ_tarM_, Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_, and Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_ Pcad_tarS_ strains (D2O; Varian; 400 mHz). Arrow points to the H-1 proton of the β-_O_-GlcNAc residue on ribitol phosphate. Peak corresponding to the amide of the C2 _N_-acetyl group attached to the sugar is identified as NHAc. Both the single knockout and the _tarS_-complemented strain produce β-O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs, but the double knockout does not. (Fig. S3) (C) Heteronuclear 13C,1H single quantum correlation (HSQC) of the WTA monomer from the RN4220 Δ_tarM strain. The H-1 proton of the β-_O_-GlcNAc residue is indicated by the arrow and confirms the signal at δ4.73 is indicative of a β-_O_-GlcNAc-ribitol-phosphate WTA monomer. These NMR data correlate with previous NMR analyses of β-_O_-GlcNAc-ribitol-phosphate WTA monomers (21, 24).

Two putative glycosyltransferase-encoding genes, designated SAOUHSC_00644 and SAOUHSC_00228, were identified in WTA operons of S. aureus NCTC8325 (Fig. S1). We used an in vitro reconstitution approach to test their function as WTA β-_O_-GlcNAc transferases. Each gene was overexpressed as an N-terminal 10-His fusion protein in Escherichia coli and purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography. The poly(RboP)-WTA substrate was synthesized in vitro using a combined chemical and enzymatic approach (Fig. 3_A_), and the purified proteins were incubated with this polymer substrate and UDP-[14C]-GlcNAc. Reaction mixtures were separated by PAGE and analyzed using phosphorimaging. No reaction was detectable under any conditions in incubation mixtures containing protein encoded by SAOUHSC_00644, and the function of this protein remains unknown. However, in reactions containing protein encoded by gene SAOUHSC_00228, the radiolabeled sugar starting material disappeared and radiolabeled products having similar mobility to [14C]-WTA polymers appeared (Fig. 3_B_). We conclude that SAOUHSC_00228 encodes a WTA glycosyltransferase, which we designated TarS.

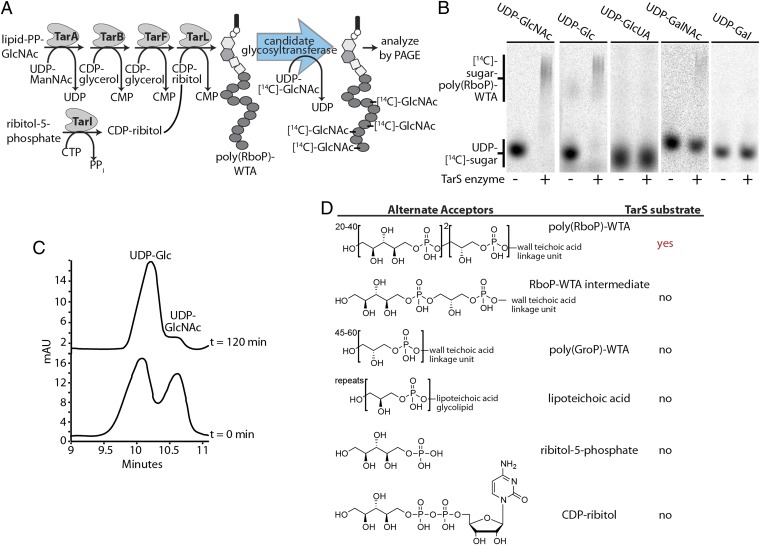

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the _O_-GlcNAc transferase, TarS, that attaches β-_O_-GlcNAc to poly(RboP)-WTAs. (A) Scheme for in vitro chemoenzymatic synthesis of poly(RboP)-WTA and its use to assay candidate β-_O_-GlcNAc WTA transferases for their ability to transfer a radiolabeled sugar to the polymer. (B) Autoradiographs of polyacrylamide gels of heat-treated (−) or active (+) TarS enzyme incubated with poly(RboP)-WTA and various [14C]-UDP-donor substrates. UDP-glucose and UDP-GalNAc are used as donor substrates, but TarS has a preference for UDP-GlcNAc (C). (C) Overlay of HPLC chromatograms (260 nm detection) of TarS incubated with equimolar amounts of UDP-glucose and UDP-GlcNAc at 0 min and 120 min. TarS reacts preferentially with UDP-GlcNAc. Injections of authentic standards were used to determine the identity of the observed peaks. (D) Structures of acceptors tested are tabulated and results are summarized (Fig. S2). The only tolerated acceptor substrate is poly(RboP)-WTA.

TarS Prefers UDP-GlcNAc as a Donor Substrate and Is Specific for Poly(Ribitol Phosphate) WTAs.

Most S. aureus strains attach _O_-GlcNAc to their WTAs, whereas other bacterial strains attach glucose, GalNAc, or other carbohydrates (15). To examine the donor specificity of TarS, we tested its ability to use four other UDP sugars as donors for glycosylation of poly(RboP)-WTA (Fig. 3_B_). The results showed that TarS can use UDP-Glc and UDP-GalNAc as alternative donor substrates, but not UDP-galactose or UDP-glucuronic acid. Thus, structural changes at either the C2 or C4 positions of the sugar donor are tolerated, although UDP-GalNAc is a far less efficient substrate than UDP-GlcNAc or UDP-Glc. In TarS reactions incubated with poly(RboP)-WTA and equimolar amounts of UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-Glc, the UDP-GlcNAc peak disappeared, whereas the UDP-Glc peak area was largely unchanged, indicating that UDP-GlcNAc is the preferred donor (Fig. 3_C_).

We tested the ability of TarS to transfer GlcNAc to possible alternate acceptors. Using different combinations of previously characterized WTA biosynthetic enzymes (25–27) we prepared a WTA pathway intermediate for acceptor testing. CDP ribitol, ribitol phosphate, lipoteichoic acid (LTA), and poly(GroP)-WTA were also tested as acceptor substrates. No glycosylation of any of these substrates was observed (Fig. 3_D_ and Fig. S2), showing that TarS is specific for substrates containing multiple RboP units. These data support the prediction that WTA glycosylation in S. aureus, as in Bacillus subtilis (28), occurs after polymer synthesis is complete.

TarS β-_O_-GlcNAcylates WTAs in S. aureus Cells.

To investigate the function of TarS in cells, we deleted tarS from wild-type RN4220 and the RN4220Δ_tarM_ strain and checked susceptibility of the mutants to phages ϕ11, ϕ52A, and ϕ80. The Δ_tarS_ strain was as susceptible to the test phage as the parental and Δ_tarM_ strains, but the Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_ double mutant was phage resistant (Fig. 2_A_). To establish the anomeric stereochemistry of the TarS product, we extracted WTAs (25) from the deletion strains and analyzed NMR spectra of their monomer units. β-O_-GlcNAcylated ribitol phosphates have an anomeric β-O_-GlcNAc 1H resonance at 4.73 ppm and a 13C resonance at 101.6 ppm (24). This peak is absent in WTAs extracted from the ∆_tarM_∆_tarS strain, but is present in WTAs from the Δ_tarM strain and the Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_ strain expressing TarS from a plasmid (Fig. 2 B and C and Fig. S3). Thus, TarS β-_O_-GlcNAcylates WTAs in S. aureus.

The WTA Polymer Backbone, but Not Its Tailoring Modifications, Is Essential for Properly Regulated Cell Division.

WTA null (Δ_tarO_) strains have several phenotypes. They are temperature sensitive, reach stationary phase at a lower density than wild-type strains, undergo Triton-X–induced autolysis at an increased rate, and show increased susceptibility to lysostaphin (13, 14). Perhaps more striking, the absence of WTAs results in massively dysregulated cell division and sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams (11). To correlate phenotypes observed in S. aureus WTA null strains with particular WTA structural features, we deleted dltA, tarM, and tarS singly and in combination from S. aureus MW2, a well-characterized community-acquired MRSA strain (29) that produces similar amounts of α- and β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs. Deleting dltA prevents attachment of d-alanyl esters to both lipo- and wall teichoic acids (15). Deleting tarM results in the expression of only β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs, deleting tarS leads to the production of only α-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs, and deleting both genes results in unglycosylated WTAs (Fig. S4_A_).

Several phenotypes of the deletion strains were examined and it was found that deletion of the O_-GlcNAc transferase genes alone or in combination had a negligible effect on cell growth rates, in vitro fitness, autolysin activation, lysostaphin susceptibility, and biofilm formation (Fig. S5). In contrast, preventing d-alanylation led to several phenotypes that are also observed in the Δ_tarO strain, either herein or in previous publications, including a decreased growth rate, increased Triton-X–induced autolysis, and decreased biofilm formation, consistent with previous studies on other Δ_dltA_ strains (17, 30).

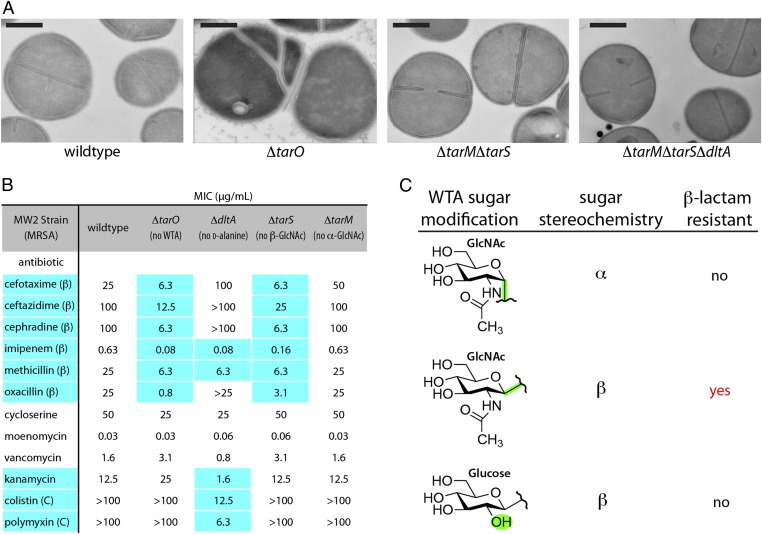

To determine whether any of the WTA substituents play a role in regulating cell division, we compared transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the mutant strains to those of the wild-type and Δ_tarO_ strains. Whereas the MW2Δ_tarO_ strain showed defects in septal placement and daughter cell separation, none of the other mutant strains, including the triple mutant lacking all WTA decorations, displayed any septal abnormalities (Fig. 4_A_ and Fig. S6). Hence, the cell division defects observed in Δ_tarO_ strains are not due to the absence of a tailoring modification, but to the absence of the anionic poly(RboP) backbone.

Fig. 4.

The anionic WTA polymer backbone, but not any tailoring modifications, is required for proper cell division. β-O_-GlcNAc WTA modifications are required for β-lactam resistance in MRSA. (A) TEM images of MW2 wild type, a WTA null strain (Δ_tarO), and two strains containing deletions in genes responsible for WTA tailoring modifications show that deleting WTAs leads to dysregulated cell division. No obvious morphological abnormalities are observed in cells lacking WTA decorations. (Scale bars, 500 nm.) (Fig. S6) (B) MIC values (μg/mL) of tested antibiotics against S. aureus strains. Data representative of at least six experiments. Highlighted values differ from wild type by at least fourfold. β, β-lactams; C, cationic antibiotics. Δ_tarS_, like Δ_tarO_, is susceptible to all tested β-lactams. Consistent with previous results, the Δ_dltA_ strain is more susceptible to cationic antibiotics than wild type. (Fig. S7 A and D) (C) Graphic table of results showing only MRSA strains that contain β-_O_-GlcNAc WTA modifications are able to maintain β-lactam resistance. MRSA strains containing β-_O_-glucose or α-_O_-GlcNAc WTA substituents are sensitive to β-lactams. MICs are tabulated in Fig. S7_C_.

WTA β-_O_-GlcNAc Modifications Are Required to Maintain β-Lactam Resistance in MRSA.

Because preventing WTA expression sensitizes MRSA strains to β-lactams by an unknown mechanism (11), we measured β-lactam minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the MW2 deletion strains to determine whether any tailoring modifications were required for resistance. Other antibiotics were included as controls (Fig. 4_B_ and Fig. S7_A_). As observed previously, the Δ_dltA_ strain was more sensitive to cationic antibiotics than wild-type S. aureus, perhaps because the increased negative surface charge density attracts cationic molecules. This strain also showed reduced MICs for methicillin and imipenem, but unlike the Δ_tarO_ strain, it was not more susceptible to several other β-lactams. The Δ_tarM_ strain showed no change in sensitivity to any antibiotics. In striking contrast however, the Δ_tarS_ strain showed increased susceptibility to the same set of β-lactams as the Δ_tarO_ strain, but not to any other antibiotics, including other cell-wall–active antibiotics. Complementation of MW2Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS_ with a plasmid expressing catalytically active TarS restored wild-type resistance levels, whereas complementation with a plasmid expressing TarM or a catalytically inactive variant of TarS did not (Figs. S4_B_ and S7 B and C). These results established that the sensitized phenotype of the tarS deletion strains is not due to polar effects, but to the lack of a functional WTA β-_O_-GlcNAc transferase. Consistent with the importance of tarS in mediating resistance, its expression was fourfold up-regulated in the presence of β-lactams, whereas the expression of tarM was unchanged (Fig. S8_A_). QRT-PCR analysis showed that expression of the gene encoding the β-lactam resistant transpeptidase PBP2a, mecA, was unaffected by tarS deletion, indicating that sensitivity is not due to down-regulation of the resistance determinant. Expression levels of several other genes implicated in β-lactam resistance, including pbp4 and fmtA, were also unaffected (Fig. S8_B_). Taken together, these results are consistent with a direct role for β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs in maintaining β-lactam resistance.

To obtain further information on the structural requirements of the WTA sugar residue in resistance, we sought to replace β-O_-GlcNAc with another β-linked sugar. B. subtilis W23 makes poly(RboP)-WTAs containing β-O_-glucose WTA modifications (31), but the tailoring enzyme had not been identified. There are four predicted glycosyltransferases, tarEMNQ, in the W23 WTA gene cluster. Since TarQ has the highest homology to TarS, we constructed two B. subtilis W23 strains, one containing a marked deletion of tarQ (W23∆_tarQ) and the other containing an additional deletion of genes tarEMN (W23Δ_Q_∆_tarEMN). Quadrupole (Q)TOF-MS analysis of extracted WTAs showed that glucosylation was absent in both mutant strains (Fig. S9_A_). Because deletion of tarQ was sufficient to abolish glucosylation, we concluded that TarQ is the primary WTA β-O_-glucosyl transferase in B. subtilis W23. The tarQ gene was therefore expressed from a plasmid in MW2Δ_tarM_Δ_tarS, and this tarQ expression strain was shown to produce WTAs modified with glucose (Fig. S9_B_). However, unlike strains expressing tarS from a plasmid, this strain was not resistant to β-lactams (Fig. S7_C_). The resistance phenotype thus depends not only on the β-anomeric configuration of the WTA sugar modification, but also on the presence of a C2 _N_-acetyl moiety (Fig. 4_C_). Hence, the structural features required for resistance are specific, suggesting that β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs establish selective interactions with other cell surface factors required for resistance.

To determine whether β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs play a role in β-lactam resistance in other MRSA strains, we deleted tarS from four additional community- and hospital-acquired MRSA strains and measured their β-lactam MICs. These tarS deletion strains were also sensitized to β-lactams (Fig. S7_D_), implying that β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs are a general resistance factor in MRSA strains. Accordingly, TarS is a possible target for small molecules that sensitize MRSA to β-lactams.

TarS Is Required for Oxacillin Resistance in a Caenorhabditis elegans Model.

The bacterivorous nematode C. elegans dies upon ingestion of pathogenic S. aureus, and is commonly used as a simple model host to evaluate the virulence of different bacterial strains in the presence and absence of antibiotics (32, 33). Using this host, we evaluated the virulence of MW2∆tarS compared with wild type, and determined bacterial susceptibility to treatment with oxacillin in vivo by evaluating nematode survival over time (Fig. S10). In the absence of antibiotic, the MW2∆tarS strain was slightly attenuated compared with wild type, suggesting a modest role for the β-O_-GlcNAc WTA moieties in pathogenesis in this system. At the highest tested dose, oxacillin partially rescued nematodes infected with wild-type MW2. In contrast, at the lowest dose tested, the antibiotic completely rescued animals infected with MW2∆_tarS. We conclude that β-_O_-GlcNAcylation of WTAs plays an important role in β-lactam resistance in vivo as it does in vitro.

Discussion

WTAs play an important role in regulating cell division in S. aureus and are also involved in maintaining resistance to β-lactams in MRSA strains (11). In this paper, we used biochemical and genetic approaches to examine the roles of the WTA polymer backbone and three tailoring modifications in these important phenotypes. We showed that the polymer backbone alone is required for properly regulated cell division because deletion of all three tailoring genes did not affect septal placement or cell separation. We also showed that a single WTA tailoring modification, β-_O_-GlcNAcylation, mediated by a newly discovered glycosyltransferase named TarS, is required to maintain wild-type levels of β-lactam resistance.

The mechanism by which β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs confer resistance to β-lactams in MRSA is not yet known. TarS deletion does not cause apparent growth or cell division defects and its deletion does not down-regulate expression of mecA or other tested genes implicated in β-lactam resistance. MRSA β-lactam resistance cannot be suppressed by expressing glycosyltransferases that incorporate either α-_O_-GlcNAcs or β-_O_-glucose residues into WTAs. Because the susceptibility phenotype seems directly attributable to the absence of the β-_O_-GlcNAc modifications on WTAs, we propose a scaffolding role for β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs in methicillin resistance. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been previously speculated that WTAs can scaffold PG synthesis and degradation proteins (11, 34–36). Moreover, a recent paper has shown that both PBP2a and FmtA directly bind WTAs in vitro (37). Polyvalent scaffolding by glycopolymers (glycolipids and glycoproteins) is a known mechanism for organizing proteins in a variety of biological processes (38, 39). Whereas there are no genes of high homology to tarS in Staphylococcus sciuri, the organism from which PBP2a was speculated to derive (40, 41), all deposited S. aureus strain sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information contain tarS. It is possible that PBP2a may exploit β-_O_-GlcNAcylated WTAs by binding to them directly or by interacting with other cellular factors that are scaffolded by these polymers. There are many genes native to S. aureus that have been shown to play a role in maintaining β-lactam resistance (7–10), including genes encoding proteins with extracellular domains that could interact with β-_O_-GlcNAc WTA tailoring modifications.

In closing, we note that there is considerable interest in compounds that restore β-lactam sensitivity to resistant microorganisms (42). Because β-lactam resistance in MRSA involves a resistant transpeptidase that depends on the function of other cellular factors for activity (4–6), compound combinations that target the activity of these other factors could be useful for overcoming MRSA infections. β-lactamase inhibitors have been highly successful as components of compound combinations to treat many β-lactam–resistant infections (2, 3). Because deletion of the tarS gene sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams, we propose that TarS is a unique target for compounds used in combination with β-lactams to treat MRSA infections.

Materials and Methods

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers for PCR amplification are listed in Table S1. More detailed methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Cloning, Overexpression, and Purification of SAOUHSC_00228 and SAOUHSC_00644.

Genes were PCR amplified from RN4220 DNA ligated into a pET-47b(+) vector (Novagen), which had been modified to a cleavable N-terminal His-tag with 10-His residues transformed into Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS cells for overexpression by isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, and 25% (vol/vol) glycerol, benzonase, and rLysozyme (Novagen) was added and the cells sonicated. The clarified lysate was purified using nickel resin. Purified protein was stored as 50% (vol/vol) glycerol stocks at either −20 °C or −80 °C. The yield is ∼5 mg/L for SAOUHSC_00228 and 33 mg/L for SAOUHSC_00644.

SAOUHSC_00228 and SAOUHSC_00644 Substrate Testing Reactions.

Three-microliter reactions containing 15 μM 228 or 130 μM 644, 20 mM Tris pH 8, 5 mM MgCl2, 63 μM UDP sugar, 7 μM UDP-[14C]-sugar, and 7 μM purified neryl-polyRboP-polymer or 5 μM UDP-[14C]-GlcNAc and 15 μM ribitol-5-phosphate, CDP-ribitol, or farnesyl-PP-GlcNAc-ManNAc-GroP-RboP were constructed. Three-microliter reactions contained 7 μM neryl-PP-GlcNAc-ManNac-GroP, 700 μM CDP-glycerol, 20 mM Tris pH 8, 5 mM MgCl2, 500 nM TagF, 10 μM 228 or 130 μM 644, 7 μM [14C]-UDP-GlcNAc, and 63μM UDP sugar. As a control to ensure TagF activity, the reaction was also set up in the same manner except with the addition of 21 μM CDP-[14C]-glycerol and cold UDP-GlcNAc. Reactions testing LTA (Sigma) were set up in a similar manner except TagF and CDP-glycerol were omitted. As a negative control, identical reactions were set up using heat-treated enzyme. After 2 h at room temperature the reactions were quenched with an equal volume of dimethylformamide and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging.

Construction of Deletion Strains.

B. subtilis W23 was transformed with linear DNA harboring a resistance cassette flanked by 1,000 bp of DNA upstream and downstream of the targeted genes (25). The RN4220 tarS gene was deleted using the pKOR1 vector, whereas, all other S. aureus gene deletions were made using the pMAD plasmid. The Δ_dltA_ strain is identical to that which was published previously (16). For MW2 deletions, the plasmid was first passaged through RN4220. The tarS/tarM deletion strains were back complemented with TarS by cloning the gene into the pLI50-PcadC shuttle expression vector under the control of a cadmium-inducible promoter. The D92A, D94A inactive TarS point mutant was made using the QuikChange Lightning (Agilent) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Sheahan, Patricia Sanchez-Carballo, and Otto Holst for NMR assistance and Christiane Goerke and Petra Kühner for RT-PCR support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 1R01AI099144 and P01AI083214 (to S.W.) and T32AI007061 (to S.B. and T.C.M.), as well as by German Research Council Grants TRR34 (to A.P.) and SFB766 (to G.X.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 18637.

References

- 1.Vollmer W, Blanot D, de Pedro MA. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:149–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapun A, Contreras-Martel C, Vernet T. Penicillin-binding proteins and beta-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:361–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher HW, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: No ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartman BJ, Tomasz A. Low-affinity penicillin-binding protein associated with beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:513–516. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.513-516.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuhashi M, et al. Molecular cloning of the gene of a penicillin-binding protein supposed to cause high resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:975–980. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.3.975-980.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinho MG, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. An acquired and a native penicillin-binding protein cooperate in building the cell wall of drug-resistant staphylococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10886–10891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191260798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger-Bächi B, Rohrer S. Factors influencing methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Arch Microbiol. 2002;178:165–171. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SH, et al. Antagonism of chemical genetic interaction networks resensitize MRSA to β-lactam antibiotics. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber J, et al. Chemical genetic identification of peptidoglycan inhibitors potentiating carbapenem activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Chem Biol. 2009;16:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Lencastre H, et al. Antibiotic resistance as a stress response: Complete sequencing of a large number of chromosomal loci in Staphylococcus aureus strain COL that impact on the expression of resistance to methicillin. Microb Drug Resist. 1999;5:163–175. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1999.5.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell J, et al. Synthetic lethal compound combinations reveal a fundamental connection between wall teichoic acid and peptidoglycan biosyntheses in Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:106–116. doi: 10.1021/cb100269f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki H, Yamaguchi T, Murakami K. Cloning and characterization of a gene affecting the methicillin resistance level and the autolysis rate in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4993–5000. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4993-5000.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swoboda JG, Campbell J, Meredith TC, Walker S. Wall teichoic acid function, biosynthesis, and inhibition. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:35–45. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia G, Kohler T, Peschel A. The wall teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid polymers of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuhaus FC, Baddiley J. A continuum of anionic charge: Structures and functions of D-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:686–723. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.686-723.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peschel A, et al. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peschel A, Vuong C, Otto M, Götz F. The D-alanine residues of Staphylococcus aureus teichoic acids alter the susceptibility to vancomycin and the activity of autolytic enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2845–2847. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2845-2847.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia G, et al. Wall teichoic Acid-dependent adsorption of staphylococcal siphovirus and myovirus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4006–4009. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May JJ, et al. Inhibition of the D-alanine:D-alanyl carrier protein ligase from Bacillus subtilis increases the bacterium’s susceptibility to antibiotics that target the cell wall. FEBS J. 2005;272:2993–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perego M, et al. Incorporation of D-alanine into lipoteichoic acid and wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis. Identification of genes and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15598–15606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia G, et al. Glycosylation of wall teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus by TarM. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13405–13415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nathenson SG, Ishimoto N, Anderson JS, Strominger JL. Enzymatic synthesis and immunochemistry of alpha- and beta-N-acetylglucosaminylribitol linkages in teichoic acids from several strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:651–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathenson SG, Strominger JL. Enzymatic synthesis and immunochemistry of N-acetylglucosaminylribitol linkages in the teichoic acids of Staphylococcus aureus stains. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:3839–3841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinogradov E, Sadovskaya I, Li J, Jabbouri S. Structural elucidation of the extracellular and cell-wall teichoic acids of Staphylococcus aureus MN8m, a biofilm forming strain. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown S, Meredith T, Swoboda J, Walker S. Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis W23 make polyribitol wall teichoic acids using different enzymatic pathways. Chem Biol. 2010;17:1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown S, Zhang Y-H, Walker S. A revised pathway proposed for Staphylococcus aureus wall teichoic acid biosynthesis based on in vitro reconstitution of the intracellular steps. Chem Biol. 2008;15:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira MP, et al. The wall teichoic acid polymerase TagF efficiently synthesizes poly(glycerol phosphate) on the TagB product lipid III. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1385–1390. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allison SE, D'Elia MA, Arar S, Monteiro MA, Brown ED. 2011. Studies of the genetics, function and kinetic mechanism of TagE: the wall teichoic acid glycosyltransferase in bacillus subtilis 168. J Biol Chem 286:23708–23716.

- 29.Baba T, et al. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet. 2002;359:1819–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross M, Cramton SE, Götz F, Peschel A. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3423–3426. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3423-3426.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin T, Burger MM, Glaser L. Synthesis of teichoic acids. VI. The formation of multiple wall polymers in Bacillus subtilis W-23. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1966;116:358–367. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irazoqui JE, et al. Distinct pathogenesis and host responses during infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sifri CD, Begun J, Ausubel FM, Calderwood SB. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model host for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2208–2217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2208-2217.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atilano ML, et al. Teichoic acids are temporal and spatial regulators of peptidoglycan cross-linking in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18991–18996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004304107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlag M, et al. Role of staphylococcal wall teichoic acid in targeting the major autolysin Atl. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:864–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankel MB, Schneewind O. Determinants of murein hydrolase targeting to cross-wall of Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10460–10471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qamar A, Golemi-Kotra D. Dual roles of FmtA in Staphylococcus aureus cell wall biosynthesis and autolysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3797–3805. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00187-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertozzi CR, Kiessling LL. Chemical glycobiology. Science. 2001;291:2357–2364. doi: 10.1126/science.1059820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avci FY, Kasper DL. How bacterial carbohydrates influence the adaptive immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couto I, et al. Ubiquitous presence of a mecA homologue in natural isolates of Staphylococcus sciuri. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:377–391. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu SW, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Recruitment of the mecA gene homologue of Staphylococcus sciuri into a resistance determinant and expression of the resistant phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2417–2424. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2417-2424.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalan L, Wright GD. Antibiotic adjuvants: Multicomponent anti-infective strategies. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e5. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information