Safety of Aspiration Abortion Performed by Nurse Practitioners, Certified Nurse Midwives, and Physician Assistants Under a California Legal Waiver (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objectives. We examined the impact on patient safety if nurse practitioners (NPs), certified nurse midwives (CNMs), and physician assistants (PAs) were permitted to provide aspiration abortions in California.

Methods. In a prospective, observational study, we evaluated the outcomes of 11 487 early aspiration abortions completed by physicians (n = 5812) and newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs (n = 5675) from 4 Planned Parenthood affiliates and Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, by using a noninferiority design with a predetermined acceptable risk difference of 2%. All complications up to 4 weeks after the abortion were included.

Results. Of the 11 487 aspiration abortions analyzed, 1.3% (n = 152) resulted in a complication: 1.8% for NP-, CNM-, and PA-performed aspirations and 0.9% for physician-performed aspirations. The unadjusted risk difference for total complications between NP–CNM–PA and physician groups was 0.87 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.45, 1.29) and 0.83 (95% CI = 0.33, 1.33) in a propensity score–matched sample.

Conclusions. Abortion complications were clinically equivalent between newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs and physicians, supporting the adoption of policies to allow these providers to perform early aspirations to expand access to abortion care.

Increased access to early abortion is a pressing public health need. By 2005, the number of abortion care facilities in the United States had decreased 38% from its peak in 1982.1 Although the number has since remained stable, the proportion of US counties with no facility remains high at 87%; more than one third of women aged 15 to 44 years live in these counties.2 Additionally, a large proportion of US facilities are hospitals that perform abortions only in cases of serious medical and fetal indications or facilities that offer medical abortions only up to 9 weeks of pregnancy.2

Many women face difficulties finding a facility, resulting in delayed care.3 Increasing access is critical because abortions at later gestations are associated with a higher risk of complications4 and higher costs.2 Research has also found that many women would prefer to obtain their abortions earlier5 Finally, traditionally underserved populations experience the greatest barriers to abortion care, resulting in higher rates of procedures after the first trimester.6,7

In California, more than half of the 58 counties lack a facility that provides 400 or more abortions (R. K. Jones, PhD, Guttmacher Institute, written communication, November 2011). Low-income and minority women are most likely to be served by public health departments or community health centers,8 most of which do not provide abortions. These women are also more likely to be cared for by nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) than by obstetricians and gynecologists.9

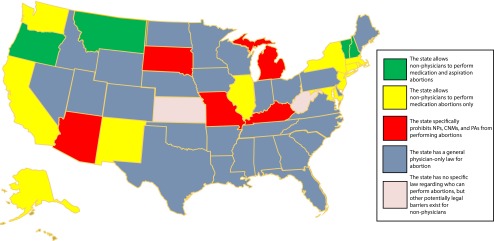

One potential solution to improve access is to increase the number and types of health care professionals who offer early abortion care.10–12 Increased emphasis has been placed on task sharing to better meet women’s health needs in the context of health care workforce shortages.13 In the United States, health professions are regulated through a patchwork of state regulations14,15 that determine who can perform abortions, a power reaffirmed by several US Supreme Court decisions.16–18 Currently, nonphysician clinicians can perform aspiration abortions legally in only 4 states—Montana, Oregon, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Two additional states (Kansas and West Virginia) do not limit the performance of abortions to physicians, but nonphysician clinicians have never tried to provide abortion care. Of the remaining 44 states (Figure 1), some allow nonphysician clinicians to perform medical (but not aspiration) abortions under decisions by attorneys general or health departments, and 1 state—California—passed statutory authority for that care. As part of a larger effort to limit abortion access, several states have recently promulgated laws that specifically prohibit nonphysician clinicians from performing abortions.19 For example, a 2009 Arizona law (HB 2564 and SB 1175) that precluded NPs from providing abortions resulted in the discontinuation of abortion care at several facilities that had previously been staffed exclusively by NPs.20

FIGURE 1—

Landscape of health professional regulation of abortion provision in the United States.

Note. CNM = certified nurse midwife; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

Limited clinical evidence is available to inform policymakers about whether physician-only legal restrictions on abortion are evidence-based.21–24 Our study was designed to provide this evidence to policymakers; it answers the question “What would be the impact on patient safety if NPs, PAs, and certified nurse midwives (CNMs) were permitted to provide aspiration abortions in California?” (We use the term aspiration abortion to refer to what is commonly called surgical abortion because the technique does not meet the technical definition of surgery.25) We used a noninferiority design to compare the incidence of abortion-related complications between groups because we anticipated a slightly higher number of complications among newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs than among the experienced physicians.

METHODS

In 2005, study investigators applied to the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) for a waiver of legal statutes that limit the completion of surgical abortion to physicians.26–28 Following a public meeting, hearing, and extensive input from stakeholders, the State of California granted approval for Health Workforce Pilot Project No. 171 in March 2007, followed by approval of 4 subsequent extensions. The study received institutional review board approvals from the University of California, San Francisco; Ethical and Independent Review Services; and Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC).

In this prospective, observational cohort study, NPs, CNMs, and PAs from 5 partner organizations (4 Planned Parenthood affiliates and KPNC) were trained to competence in the provision of aspiration abortion (a minimum of 40 procedures over 6 clinical days, with competence assessed by an authorized physician trainer). To be qualified for training, NPs, CNMs, and PAs had to have a California professional license, basic life support certification, and 12 months or more of clinical experience, including 3 months or more experience in medication abortion provision. Physicians employed by the facility served as the comparison group. A total of 28 NPs, 5 CNMs, and 7 PAs (n = 40) and 96 physicians (with training in either family medicine or obstetrics and gynecology) completed procedures during the study period. Physicians had a mean of 14 years of experience providing abortions compared with a mean of 1.5 years among NPs, CNMs, and PAs. This analysis did not include procedures performed by NPs, CNMs, and PAs during their training phase.

Patients were enrolled at 22 clinical facilities between August 2007 and August 2011. Patients were eligible for the study if they were aged 16 years or older (18 years at Planned Parenthood affiliates), were seeking a first-trimester aspiration abortion (facilities self-defined this as ≤ 12 or ≤ 14 weeks’ gestation by ultrasound), and could speak English or Spanish. Patients were excluded if they requested general anesthesia or did not meet the health-related criteria (unexplained historical, physical, or laboratory findings or known or suspected cervical or uterine abnormalities).

Study Procedures

Eligible patients reviewed a consent form with a facility staff member. If a patient agreed to participate, she was asked whether she was willing to have her abortion done by an NP, CNM, or PA; if so, the aspiration was performed by the NP, CNM, or PA on duty. Patients in this group were routed to a physician if clinical flow necessitated reorganizing patients. Patients were also routed to a physician if they were unwilling to have their abortions performed by an NP, CNM, or PA or arrived for care when only a physician was present.

Each patient received $5 and a follow-up survey about medical problems after the abortion to capture any delayed postprocedure complications. If patients did not return the survey, clinic staff made at least 3 attempts to administer the survey by phone. If the patient experienced postabortion problems, she was asked a defined set of questions to obtain medical details. Additionally, staff conducted patient chart abstractions 2 to 4 weeks after abortion to ensure delayed complications were captured. For all outcomes other than an uncomplicated recovery, an incident report was generated and reviewed by the site medical director, study investigators, and the study’s Data and Clinical Safety Monitoring Committee. Additional monitoring of outcomes and study procedures included annual Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development–sponsored site visits; quarterly reviews of participant recruitment, patient experience, and clinical outcomes; and routine communication between facility and UCSF study staff.

Study Outcomes

Unlike a superiority analysis, a noninferiority study design determines whether the effect of a new treatment is not worse than that of an active control by more than a specified clinically acceptable margin.29–32 We selected a noninferiority design because we were seeking not to replace physicians as abortion providers or to determine whether NPs, CNMs, and PAs were better than current providers of care but to identify additional, comparably safe providers to supplement the provider pool. Because NPs, CNMs, and PAs who are newly trained in aspiration abortion have less experience, we expected to find a statistically significant higher rate of complications among this group than among more experienced physicians. However, we also anticipated a low overall incidence of complications from procedures across both groups. Therefore, a noninferiority design provided a more clinically relevant analysis. Given a low expected complication rate in both provider groups, we prespecified the margin of noninferiority as a change of 2%, which was determined before the start of the study by a panel of researchers and clinicians and approved by the Data and Clinical Safety Monitoring Committee, who considered ethical and clinical issues and previous US-based studies, which showed abortion-related complication rates ranging from 1.3% to 4.4%.21,22,33–38

The primary outcome was the difference in incidence of complications within 4 weeks of the aspiration abortion between NPs, CNMs, and PAs and physicians. Complications were categorized as immediate (occurring before leaving the facility) and delayed (occurring ≤ 4 weeks after the procedure). Additionally, complications were classified as major if the patient required hospital admission, surgery, or a blood transfusion and minor if they were treated at home or in an outpatient setting. This classification schema is consistent with that used in other studies of abortion-related morbidity.34–37

Statistical Analysis

We based sample size calculations for this study on an expected complication rate of 2.5%, which was based on mean complication rates cited in the published literature21,22,33–38 and powered at 90% to detect a 1.0% or greater difference in complication incidence between groups (α = .025, 1-tailed test). The study was powered specifically for a noninferiority analysis. Although we set a clinically acceptable margin of difference at 2.0%, we took a conservative approach and powered the study to detect an even smaller difference. We then further increased the sample size per group by 15% to adjust for clustering effects at the provider and clinic levels.

We compared sociodemographic characteristics of patients seen by NPs, CNMs, and PAs and those seen by physicians using mixed-effects logistic regression for dichotomous variables, mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression for categorical variables, and mixed-effects linear regression for continuous variables, all of which included random effects for facility. Incidence of a complication was coded as a dichotomous variable. Complication incidence was calculated by provider group. We fit a mixed-effects logistic regression model with crossed random effects to obtain odds ratios that account for the lack of independence between abortions performed by the same clinician and within the same facility and cross-classification of providers across facilities. We included variables associated with complications in bivariate analyses at P < .05 in the multivariate model in addition to other clinically relevant covariates to adjust for potential confounders.

To mitigate selection bias resulting from the lack of randomization, we replicated the analysis in a propensity score–matched sample, a method used to achieve balance between study groups in observational or nonrandomized studies using the predicted probability of group membership (NP, CNM, or PA vs physician group) on the basis of observed predictors.39–41 We used the Stata module pscore to develop the propensity scores based on a logistic regression model that included patient characteristics that potentially influenced to which provider type the patient was assigned (age, race/ethnicity, insurance type, gestational age, parity, history of cesarean delivery, history of miscarriages, history of abortions, screening for sexually transmitted infections, positive test for a sexually transmitted infection, selection of a clinical contraceptive method, and presence of risk factors). Patients with similar propensity scores in the 2 provider groups were matched using nearest neighbor matching. After testing that the balancing property of the propensity score was satisfied, we selected a matched sample composed of 78.3% of the original sample, among which we replicated our mixed-effects analysis. We used predictive probabilities to calculate risk differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all models. We used STATA version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 21 095 women were screened for eligibility. Of these, 3837 did not meet the eligibility criteria, most commonly because of patient age and gestational age. Among the 17 258 eligible women, 13 807 agreed to participate in the study. Of these, 2320 had procedures performed by NPs, CNMs, and PAs during their training phase and were therefore not included in this analysis. As a result of a protocol violation at 1 site, 79 patients in the physician group were excluded. Follow-up data were available for 69.5% of patients, and follow-up rates were nondifferential between provider groups. Patients who did not return the follow-up survey were retained in the analytic sample because we found that they contacted the facility when they did experience a complication (n = 41), which we also discovered via medical chart abstraction, suggesting a low likelihood of missing complications among this group. Additionally, in a sensitivity analysis, complication incidence and risk differences were similar when we excluded patients who did not return the follow-up survey. Patients without follow-up data were more likely to have no insurance, have fewer risk factors, be multigravida, and be at less than 5 weeks gestation than were those with follow-up data (P < .05; not shown). The final analytic sample size was 11 487; of these procedures, 5812 were performed by physicians and 5675 were performed by NPs, CNMs, or PAs.

Patient Characteristics

The majority of women in both groups had had 3 or more pregnancies; no previous cesarean deliveries, miscarriages, or induced abortions; and no history of medical risk factors (Table 1). Women in the NP–CNM–PA group were more likely to be younger (P < .01), less likely to be Asian than White (P < .01), and more likely to be non-Hispanic Black than White (P < .03). Women were similar on all other sociodemographic characteristics across provider groups.

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics of Patient Study Participants by Provider Type at 22 California Clinical Facilities: August 2007–August 2011

| Patient Characteristic | Physicians (n = 5812), % or Mean ±SD | NPs–CNMs–PAs (n = 5675), % or Mean ±SD | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 25.7 ±6.1 | 25.6 ±5.9 | .01 |

| 16–19 | 12.9 | 13.5 | .73 |

| 20–24 (Ref) | 39.0 | 39.0 | |

| 25–34 | 36.9 | 37.4 | .83 |

| ≥ 35 | 11.2 | 10.1 | .06 |

| Race/ethnicityb | |||

| White, non-Hispanic (Ref) | 29.3 | 29.5 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 12.1 | 13.8 | .03 |

| Hispanic | 40.6 | 40.4 | .87 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 8.3 | 6.6 | .01 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 8.7 | 8.5 | .83 |

| Insurance type | |||

| No coverage (Ref) | 24.7 | 26.5 | |

| Medi-Calc | 56.3 | 54.1 | .68 |

| Private | 11.9 | 14.1 | .67 |

| Other | 7.1 | 5.3 | <.001 |

| Gestational age, d | |||

| < 36 (Ref) | 2.5 | 2.7 | |

| 36–49 | 31.5 | 33.3 | .26 |

| 50–63 | 32.1 | 33.1 | .36 |

| ≥ 64 | 33.9 | 30.9 | .93 |

| Gravidity | |||

| ≤ 1 (Ref) | 27.2 | 26.9 | |

| 2 | 20.6 | 21.5 | .25 |

| 3 | 18.3 | 17.4 | .55 |

| ≥ 4 | 33.9 | 34.1 | .59 |

| Parityd | |||

| 0 (Ref) | 44.2 | 44.9 | |

| 1 | 24.8 | 24.1 | .63 |

| ≥ 2 | 30.8 | 30.7 | .97 |

| Previous cesarean deliveries | |||

| 0 (Ref) | 86.5 | 86.7 | |

| ≥ 1 | 13.5 | 13.3 | .21 |

| Previous miscarriagese | |||

| 0 (Ref) | 82.3 | 82.7 | |

| 1 | 13.9 | 13.2 | .2 |

| ≥ 2 | 3.5 | 3.6 | .99 |

| Previous induced abortionsf | |||

| 0 (Ref) | 52.3 | 51.5 | |

| 1 | 28.0 | 28.6 | .46 |

| ≥ 2 | 19.5 | 19.6 | .7 |

| Tested positive for an STI | 3.6 | 3.4 | .77 |

| Risk factorsg | |||

| Extreme obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) | 2.3 | 2.2 | .33 |

| Existing chronic illness | 5.0 | 4.9 | .72 |

| Placenta previa (16–18 wk) | 0.0 | 0.0 | .32 |

| Psychiatric condition | 3.3 | 3.2 | .61 |

Outcomes

Overall, complications were rare (Table 2). Out of 11 487 aspiration abortions, 1.3% (n = 152; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.53) resulted in a complication; 1.8% of NP-, CNM-, and PA-performed aspirations and 0.9% of physician-performed aspirations resulted in a complication. The majority of complications (146/152, or 96%) were minor (1.3% of all abortions) and included cases of incomplete abortion (n = 9 among physicians, n = 24 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), failed abortion (n = 7 among physicians, n = 11 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), bleeding not requiring transfusion (n = 2 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), hematometra (n = 3 among physicians, n = 16 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), infection (n = 7 among physicians, n = 7 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), endocervical injury (n = 2 among physicians, n = 2 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), anesthesia-related reactions (n = 1 among physicians, n = 1 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs), and uncomplicated uterine perforation (n = 3 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs). We classified complications without clear etiology but accompanied by patient symptoms as symptomatic intrauterine material (n = 16 among physicians, n = 24 among NPs, CNMs, and PAs). We classified 11 minor complications as “other”; 4 were from physician-performed procedures (1 urinary tract infection, 1 possible false passage, 1 probable gastroenteritis, 1 unspecified allergic reaction), and 7 were from NP-, CNM-, or PA-performed procedures (1 fever of unknown origin, 1 intrauterine device–related bleeding, 3 sedation drug errors, 1 inability to urinate, 1 vaginitis).

TABLE 2—

Overall and Major and Minor Complication Rates by Provider Type at 22 California Clinical Facilities: August 2007–August 2011

| Physicians (n = 5812) | NPs–CNMs–PAs (n = 5675) | Total (n = 11 487) | Risk Difference Between Provider Groups (n = 11 487) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication Type | Rate/100 (95% CI) | No. | Rate/100 (95% CI) | No. | Rate/100 (95% CI) | No. | Difference in Rate/100 (95% CI) |

| Major | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) | 3 | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) | 3 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 6 | 0.001 (−0.08, 0.09) |

| Minor | 0.84 (0.61, 1.08) | 49 | 1.71 (1.37, 2.05) | 97 | 1.27 (1.07, 1.48) | 146 | 0.87 (0.46, 1.28) |

| Total | 0.89 (0.65, 1.14) | 52 | 1.76 (1.42, 2.10) | 100 | 1.32 (1.11, 1.53) | 152 | 0.87 (0.45, 1.29) |

Only 6 major complications occurred (3 in each provider group), which included 2 uterine perforations, 3 infections, and 1 hemorrhage. We found no difference in risk of major complications between provider groups: 0.001% (95% CI = −0.08, 0.09).

The overall unadjusted risk difference for total complications between NPs, CNMs, and PAs and physicians was 0.87% (95% CI = 0.45, 1.29). The risk difference in immediate complications (n = 9 for physicians; n = 20 for NPs, CNMs, and PAs) was 0.20% (95% CI = 0.01, 0.38); for delayed complications (n = 43 for physicians; n = 80 for clinicians), it was 0.67% (95% CI = 0.29, 1.10).

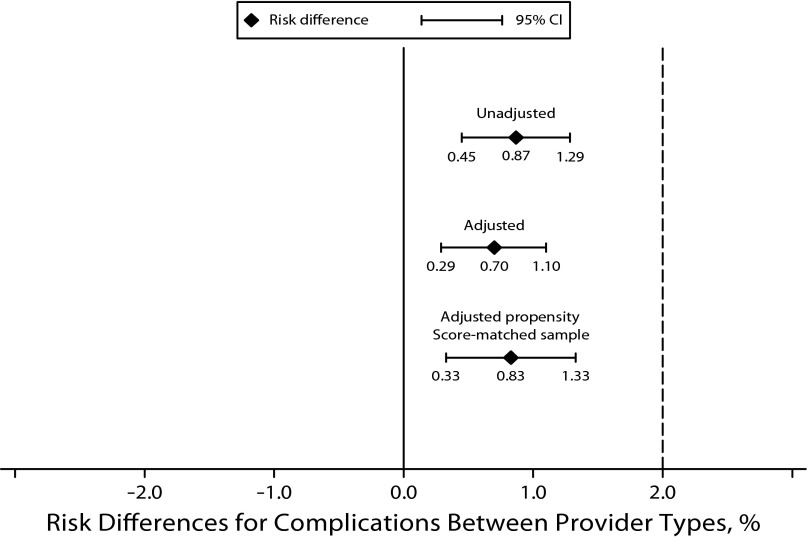

Abortions by NPs, CNMs, and PAs were 1.92 (95% CI = 1.36, 2.72) times as likely to result in a complication as those performed by physicians after adjusting for potential confounders (see table available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Among the propensity score-matched sample, complications were 2.12 (95% CI = 1.33, 3.37) times as likely to result from abortions by NPs, CNMs, and PAs as by physicians. The corresponding risk differences were 0.70% (95% CI = 0.29, 1.10) in overall complications between provider groups in the adjusted model and 0.83% (95% CI = 0.33, 1.33) in the propensity score–matched sample. The estimated 95% CIs for risk differences in unadjusted, adjusted, and propensity score–matched analyses all fell well within the predetermined margin of noninferiority, and therefore complication rates from aspiration abortions performed by recently trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs were statistically no worse than those from those performed by the more experienced physician group (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Unadjusted, adjusted, and adjusted propensity score–matched risk differences in overall complication rates of first-trimester aspiration abortion by nurse practitioner, certified nurse midwife, and physician assistant providers compared with physician providers in California.

Note. CI = confidence interval. Both adjusted models included patient age, race/ethnicity, insurance type, gestational age, gravidity, history of cesarean section, positive test for a sexually transmitted infection, an indicator for extreme obesity, an indicator for chronic illness, and an indicator for psychiatric conditions. 2.0 is also the delta.

DISCUSSION

In 2008, 1.21 million abortions took place in the United States, with more 200 000 (18%) in the State of California.2 Nationally, 92% of abortions take place in the first trimester,7 but Black, uninsured, and low-income women have less access to this care.6 In California, only 87% of women using state Medicaid insurance obtain abortions in the first trimester.42 Because the average cost of a second-trimester abortion is substantially higher than that of a first-trimester procedure, shifting the population distribution of abortions to earlier gestations would result in safer, less costly care. Increasing the types of health care professionals involved in abortion care is one way to reduce this health care disparity.

Our study was designed to examine the effect of removing the physician-only requirement for aspiration abortion provision in California. We found that the care provided by newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs was not inferior to that provided by experienced physicians. We estimate that only 1 additional complication would occur for every 120 procedures as a consequence of having an NP, CNM, or PA as the abortion provider. Additionally, the 0.83% risk difference was mainly the result of higher incidence of minor complications, the majority of which were from diagnoses easily treated and without consequential sequelae. Moreover, on the basis of findings in other studies, we expect this risk difference to narrow further over time.43–45 The comparison of newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs with more experienced physician abortion providers suggests that the small difference found would represent the maximum variation in outcomes that might be expected immediately after a policy change.

Both provider groups had extremely low numbers of complications, less than 2% overall—well below published rates—and only 6 complications out of 11 487 procedures required hospital-based care. Because the effect size is minimal compared with the published data and within the prespecified margin of noninferiority, we conclude that the difference between the 2 groups of providers is not clinically significant.

While the reported odds ratios comparing complication rates from procedures performed by NPs, CNMs, and PAs with those from procedures performed by physicians were statistically significant, these results should be interpreted cautiously. The study was powered specifically for a noninferiority analysis, which necessitated a larger sample size than a superiority analysis would. Therefore the significance we see may be a result of the study being overpowered.

These findings support the adoption of policies that increase access to abortion by expanding the number and type of health care professionals who can perform early aspiration abortions. The benefits of expanding access to abortion for California’s women outweigh the small initial difference in risk, particularly because it would likely move many second-trimester abortions into the first trimester, significantly decreasing the overall risk of complications, which increases with gestational age.4 Expanded access is also likely to afford more women the opportunity to obtain care without the additional indirect costs associated with traveling to a geographically distant abortion provider.

The strengths of this study are its statistical power, the large number of providers, and its setting in multiple facilities. A limitation of the study is its nonrandomized design, although the use of propensity score matching allowed for statistical adjustments to address this limitation. Additionally, this study had a low follow-up rate (70%), but this was not unexpected because of the sensitive nature of abortion, which may have deterred women from continuing participation in the study after the procedure. This follow-up rate is also similar to those in other US abortion-related studies with comparable follow-up periods (14–28 days).22,37,46 Although postprocedure complications may have been missed among patients for whom we did not have follow-up data, given the nondifferential follow-up rates between provider groups, we would expect unidentified complications to be equally distributed between groups, leaving the risk difference unaffected. A further limitation of the study is that the health care provider who initially identified a complication was not blinded to the type of provider who performed the abortion. However, we hypothesize that complaints from patients cared for by newly trained NPs, CNMs, and PAs would be more aggressively evaluated if the provider type was known to the health care provider evaluating the patient. Therefore, any bias caused by lack of blinding would have resulted in an overestimate of the risk difference.

Our results confirm existing evidence from smaller studies that the provision of abortion by NPs, CNMs, and PAs is safe21,22 and from larger international13 and national47 reviews that have found these clinicians to be safe and qualified health care providers. The value of this study extends beyond the question of who can safely perform aspiration abortion services in California because it provides an example of how research can be used to answer relevant health workforce policy issues. As the demand for health care providers increases under US health care reform,48 one part of the solution for all health care, including abortion care, is to allow all qualified professionals to perform clinical care to the fullest extent of their education and competency.49,50

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from private foundations including the John Merck Foundation, the Educational Foundation of America, the David & Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Susan Thompson Buffet Foundation. In addition, the research was conducted under a legal waiver from the California Health Workforce Pilot Project Program, a division of the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

We are grateful for the work of the partner organization principal investigators: Mary Gatter, MD, Katharine Sheehan, MD, Dick Fischer, MD, Debbie Postlethwaite, NP, MPH, and Amanda Calhoun, MD. Additional gratitude is extended to two former University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)-based research managers, Deborah Karasek, MPH, and Kristin Nobel, MPH; UCSF-based project manager Patricia Anderson, MPH; former UCSF-based legal team Jennifer Dunn, JD, and Erin Schultz, JD; clinical education consultant Amy Levi, PhD, CNM; statistical consultant John Boscardin, PhD, through the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute; health regulation consultant Barbara Safriet, JD; and the site-specific research coordinators. Finally, Maureen Paul, MD, MPH, and Suzan Goodman, MD, MPH, were instrumental in the early design of this project.

Human Participant Protection

Study protocol and procedures received institutional review board approvals from the University of California, San Francisco; Ethical and Independent Review Services; and Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

References

- 1.Jones RK, Zolna MR, Henshaw SK, Finer LB. Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(1):6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drey EA, Foster DG, Jackson RA, Lee SJ, Cardenas LH, Darney PD. Risk factors associated with presenting for abortion in the second trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HBet al. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Timing of steps and reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States. Contraception. 2006;74(4):334–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RK, Finer LB. Who has second-trimester abortions in the United States? Contraception. 2012;85(6):544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pazol K, Zane SB, Parker WY, Hall LR, Berg C, Cook DA. Abortion surveillance–United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(15):1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schacht J. The Vital Role of Community Clinics and Health Centers: Assuring Access for All Californians. Sacramento, CA: California Primary Care Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grumbach K, Hart LG, Mertz E, Coffman J, Palazzo L. Who is caring for the underserved? A comparison of primary care physicians and nonphysician clinicians in California and Washington. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(2):97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimes DA. Clinicians who provide abortions: the thinning ranks. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(4):719–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darney PD. Who will do the abortions? Womens Health Issues. 1993;3(3):158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor D, Safriet B, Weitz T. When politics trumps evidence: legislative or regulatory exclusion of abortion from advanced practice clinician scope of practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;54(1):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renner RM, Brahmi D, Kapp N. Who can provide effective and safe termination of pregnancy care? A systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120(1):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christian S, Dower C, O'Neil E. Overview of Nurse Practitioner Scopes of Practice in the United States - Discussion. San Francisco, CA: Center for the Health Professions, UCSF; 2007. Available at: http://www.acnpweb.org/files/public/UCSF_Discussion_2007.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finocchio LJ, Dower CM, McMahon T, Gragnola CM. Taskforce on Health Care Workforce Regulation. Reforming Healthcare Workforce Regulation: Policy Considerations for the 21st Century. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commission; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe v Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 149 (1973).

- 17.Connecticut v Menillo, 423 U.S. 9 (1975).

- 18.Mazurek v Armstrong, 520 U.S. 968 (1997).

- 19.Burke DM, ed. Defending Life 2010: Proven Strategies for a Pro-Life America: A State-by-State Legal Guide to Abortion, Bioethics, and the End of Life. Washington, DC: Americans United for Life; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rough G. Planned Parenthood to end abortions at 7 Arizona sites. Arizona Republic. August 19, 2011. Available at: http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/2011/08/18/20110818arizona-planned-parenthood-ends-abortion-3-cities.html. Accessed December 21, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman MA, Jillson DA, Coffin RR, Novick LF. Comparison of complication rates in first trimester abortions performed by physician assistants and physicians. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(5):550–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman MB, Occhiuto JS, Peterson LE, Zapka JG, Palmer RH. Physician assistants as providers of surgically induced abortion services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1352–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warriner IK, Meirik O, Hoffman Met al. Rates of complication in first-trimester manual vacuum aspiration abortion done by doctors and mid-level providers in South Africa and Vietnam: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1965–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jejeebhoy SJ, Kalyanwala S, Zavier AJet al. Can nurses perform manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) as safely and effectively as physicians? Evidence from India. Contraception. 2011;84(6):615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitz TA, Foster A, Ellertson C, Grossman D, Stewart FH. “Medical” and “surgical” abortion: rethinking the modifiers. Contraception. 2004;69(1):77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cal Code of Regulations §1399.5411.

- 27.Cal Code §75043.

- 28.Cal Business Professions Code §2253.

- 29.Chan IS. Proving non-inferiority or equivalence of two treatments with dichotomous endpoints using exact methods. Stat Methods Med Res. 2003;12(1):37–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohmel J, Mansmann U. Unconditional Non-Asymptotic One-Sided Tests for Independent Binomial Proportions When the Interest Lies in Showing Non-Inferiority and/or Superiority. Biometrical J. 1999;41(2):149–170. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gøtzsche PC. Lessons from and cautions about noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1172–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1152–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakim-Elahi E, Tovell HM, Burnhill MS. Complications of first-trimester abortion: a report of 170,000 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76(1):129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett IM, Baylson M, Kalkstein K, Gillespie G, Bellamy SL, Fleischman J. Early abortion in family medicine: clinical outcomes. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(6):527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg AB, Dean G, Kang MS, Youssof S, Darney PD. Manual versus electric vacuum aspiration for early first-trimester abortion: a controlled study of complication rates. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macisaac L, Darney P. Early surgical abortion: an alternative to and backup for medical abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(2, suppl):S76–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul ME, Mitchell CM, Rogers AJ, Fox MC, Lackie EG. Early surgical abortion: efficacy and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westfall JM, Sophocles A, Burggraf H, Ellis S. Manual vacuum aspiration for first-trimester abortion. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(6):559–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat. 2002;84(1):151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imbens G. The role of the propensity score in estimating dose-response functions. Biometrika. 2000;87(3):706–710. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 42.California Department of Health Care Services. Medi-Cal Funded Induced Abortions Calendar Year 2007. Medi-Cal Report. Sacramento, CA: Research and Analytical Studies Section, Department of Health Care Services; 2009. Available at: http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/statistics/Documents/Induced_Abortions_2007.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2012.

- 43.Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Cates WJ., Jr Prevention of uterine perforation during curettage abortion. JAMA. 1984;251(16):2108–2111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulz KF, Grimes DA, Cates W., Jr Measures to prevent cervical injury during suction curettage abortion. Lancet. 1983;321(8335):1182–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Child TJ, Thomas J, Rees M, MacKenzie IZ. Morbidity of first trimester aspiration termination and the seniority of the surgeon. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(5):875–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grossman D, Ellertson C, Grimes DA, Walker D. Routine follow-up visits after first-trimester induced abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KMet al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(5):230–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Changes In Healthcare Professions’ Scope of Practice. Legislative Considerations. Chicago, IL: National Council of State Boards of Nursing; 2009. Available at: https://www.ncsbn.org/ScopeofPractice_09.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2012.

- 50.Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing at the Institute of Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Institute of Medicine. (U.S.). The future of nursing: leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]