Beyond DSM and ICD: introducing “precision diagnosis” for psychiatry using momentary assessment technology (original) (raw)

In medicine, a diagnostic system should ideally be mechanism-based rather than symptom-based. Although attempts to create diagnostic entities in psychiatry that are based on specific biological mechanisms have failed 1, new evidence suggests that an alternative mechanistic approach, based on mental mechanisms, can be readily implemented in psychiatry, complementing the widely criticized categorical systems of DSM and ICD.

Below, we describe the contours of a novel system of diagnosis in psychiatry based on: a) the need for a more individualized approach, based on causal influences in symptom circuits (“precision diagnosis”); b) the need to take into account the fact that symptoms reflect responses to context (“context diagnosis”); c) the need to take into account that syndromes develop over time and have recognizable stages of expression (“staging diagnosis”) 2; and d) the need for the diagnostic process to become collaborative rather than unidirectional, reflecting the first stage of collaboration between patient and professional, and the first stage of treatment.

The proposed diagnostic system is based on novel digital momentary assessment technology, which allows the patient to collect data on symptoms and contexts in the flow of daily life, from which detailed contextual symptom circuits can be constructed, that serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, as well as an instrument to assess change.

THE PRINCIPLE OF CONTEXTUAL PRECISION DIAGNOSIS

The main problem with psychiatric diagnosis is that groups identified by a common label, for example schizophrenia, in fact have little in common. The level of heterogeneity in terms of psychopathology, need for care, treatment response, illness course, cognitive vulnerabilities, environmental exposures and biological correlates is so great that it becomes implausible that these labels can provide much clinical utility.

In other areas of medicine, unexplained heterogeneity was addressed by the introduction of precision (or personalized) diagnosis. For example, blood pressure, plasma glucose, cardiac rhythm, electroencephalogram, muscle tone and other somatic outcomes can now be monitored in daily life, allowing for a diagnosis that yields individualized information about the pattern of variation of the parameter in question in response to daily life circumstances. This diagnostic information is precise, as it reflects highly personal patterns of variation, and is contextual, as it traces variation related to daily life circumstances of, for example, stress, sleep, medication and life style. It is also collaborative, as the patient is actively involved in collecting and interpreting the diagnostic data. This not only enables precise indexing of treatment needs (diagnosis), but also precise monitoring of treatment response (prognosis). A similar system of contextual precision diagnosis may be useful in psychiatry.

PRECISION: DIAGNOSING MENTAL CAUSATION IN SYMPTOM CIRCUITS

How can diagnosis based on psychopathology be similarly individualized? To date, the most commonly used attempt at individualization is based on assigning individuals to diagnostic categories, in combination with personalized ratings of psychopathology across different dimensions. In theory, this system of “dimensionalized categories” ought to yield acceptable precision, given that two individuals within the same diagnostic category will nearly always have different psychopathological profiles.

Recent research, however, indicates that this system is based on the false premise that symptoms always vary together as a function of a latent underlying dimension or category – which does not appear to be the case 3,4. Instead, it has been argued that mental “disorders” in fact may represent sets of symptoms that are connected through a system of causal relations, which may explain individualized co-occurrence of different symptoms 4,5. For example, the negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia have largely independent courses 6, and etiological factors appear to operate at the symptom level rather than the diagnostic disorder level 7–9.

Therefore, there is increasing interest in how multiple symptoms in individuals arise not as a function of a latent construct, but as a function of symptoms impacting on each other, for example insomnia impacting on depressive symptoms 10 or on paranoia 11, depressive symptoms impacting on anxiety symptoms 12, affective disturbance giving rise to psychosis 13,14, negative symptoms predicting psychosis 15, and hallucinations impacting on delusions 16,17. Not only between-symptom dynamic relationships have been described, but intra-symptom temporal dynamics resulting in persistence or, in momentary assessment technology terms, momentary transfer of symptoms have been observed. For example, intra-symptom dynamics over time, in the form of intra-symptom feedback loops, have been described in the area of psychosis, both at the momentary “micro-level” over the course of a single day in daily life 18, or over the course of months or years 19,20, under the influence of genetic and non-genetic risk factors 21–23.

The notion that traditional diagnostic categories and dimensions need to be transformed to represent the dynamics of symptoms impacting on each other over time in a model of mental mechanisms or mental causation is tantalizing. It implies that special methodology is required to collect repeated measures of symptoms over time in the flow of daily life, both at the momentary level and over more extended periods 24. This type of information allows for a detailed analysis and systematic presentation 25 of how symptoms impact each other 4,5,18.

CONTEXT: DIAGNOSING ENVIRONMENTAL REACTIVity

Although it is widely believed that mental disorders have their origin in altered cerebral function, disease categories as defined in DSM and ICD do not map on to what the brain actually does: mediating the continuous flow of meaningful perceptions of the social environment that guide adaptive behaviour. The use of ex-cathedra static diagnostic categories appears distal from the neural circuits that mediate dynamic adaptation to social context.

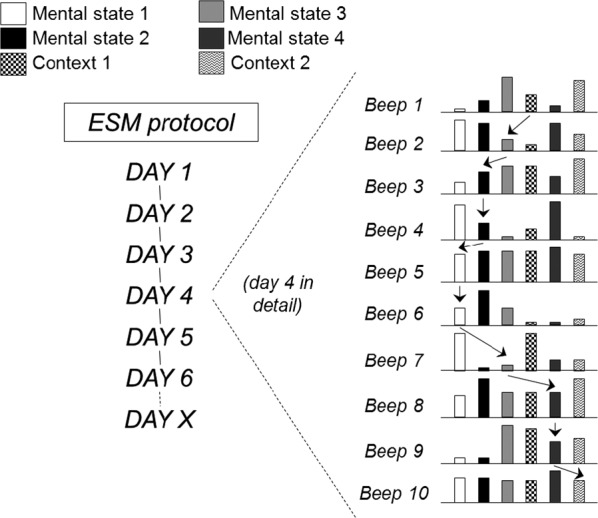

Therefore, reformulation of the basic psychopathological unit towards capturing dynamic reactivity, modelled on the role of neural circuits in mediating adaptive functioning to social context, may be productive in the context of diagnosis. Momentary assessment technology phenotypes capturing dimensional variation in mental states in response to other mental states in the symptom circuit on the one hand, and to environmental variation on the other, are well placed to fill these requirements (Figure 1), resulting in a diagnosis that is both contextual and precise.

Figure 1.

Momentary assessment with the Experience Sampling Method (ESM). At 10 random moments during the day, mental states (e.g., anxiety, low mood, paranoia, being happy) and contexts (stress, company, activity, drug use) are assessed. The arrows represent examples of prospectively analyzing the impact of mental states and contexts on each other over time.

It is proposed that momentary assessments of contextual symptom circuits, using the Experience Sampling Method (ESM), will provide a fertile model for investigation of psychopathology, encompassing phenotypes at multiple levels of neurofunctional organization 26. For example, momentary assessment technology studies of exposure to early trauma in humans have yielded replicated evidence that early environmental exposures predict altered momentary response to stress in adulthood that increase the risk of mental disorder 27–29. There is a suggestion that these ESM phenotypes of behavioural sensitization 30 can be linked to biological models of sensitization 31,32, thus suggesting that the momentary environmental reactivity may represent a key variable in linking mental and neurobiological phenotypes 33. Also, several ESM mental state measures have shown that connections between momentary mental states and environments are sensitive to genetic effects, not just in terms of heritability and familial resemblance 34,35, but particularly in terms of the genetics underlying environmental sensitivity 36–43, a mechanism referred to as gene-environment interaction.

EMPOWERMENT: A COLLABORATIVE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

In the momentary assessment paradigm of diagnosis as described above, patients collect their own data in daily life, and not only assist in observing variation in mental states, but also learn about daily environments likely to induce changes therein. Their experiences are assessed and translated in the diagnostic paradigm. For example, tracking aberrant salience can be explained as “let's follow how you tend to put some issues under a magnifying glass”, or “let's see what kind of environment helps you to generate positive affect”. This stimulates awareness and involves patients in making their own diagnosis, both at the level of psychopathology and at the level of functioning, relevant for both treatment and rehabilitation. During treatment, patients can directly observe how treatment impacts their dynamically varying mental states in response to environmental challenges in the flow of daily life. Patients thus become empowered to evaluate their own diagnosis and treatments in daily life, outside the doctor's office. Doctors, in turn, are given access to a much more accurate, prospective measurement of the phenotype of mental disorder: rather than a static cross-sectional measure that is not representative of what the patient experiences outside the doctor's office, they now have access to the true phenotype of continuous and dynamic variation in response to environmental challenges in the flow of daily life, allowing them to not only prescribe treatments, but also life style alterations targeting challenging environments.

PRECISION DIAGNOSIS IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

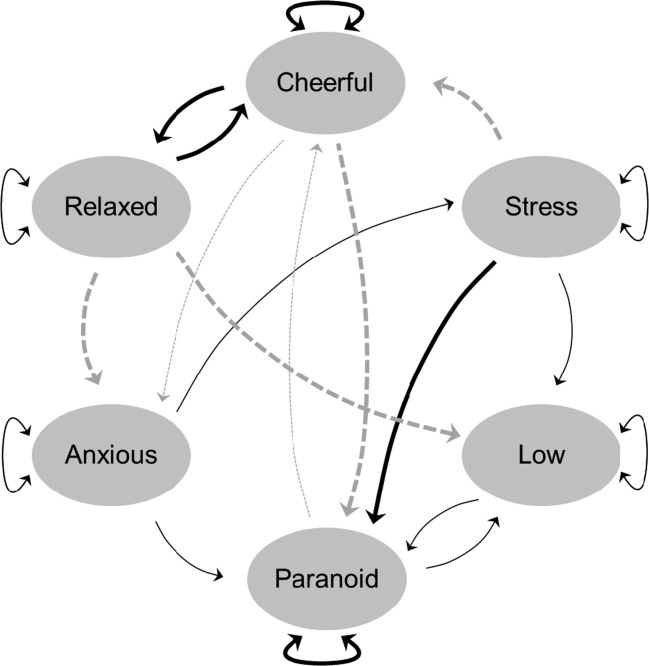

An example of contextual precision diagnosis is depicted in Figure 2. “Diagnosis” here refers to the visual display of causal relationships between symptoms and environment (in the example: stress) in the circuit. The circuit not only focuses on environment and symptoms, but also includes positive affective states, thus increasing therapeutic relevance.

Figure 2.

Contextual precision diagnosis. Thicker lines indicate stronger associations. The (simulated) patient in this example did 6 days of experience sampling in order to determine circuit patterns of stress and mutually impacting mental states. The resulting causal circuit is depicted. A strong positive (black lines) feedback loop exists between positive states (relaxed and cheerful) and a negative (dotted grey lines) feedback loop exists between the opposite mental states of being cheerful and being paranoid. Stress occasions paranoia and impacts negatively on cheerfulness. Being relaxed helps reducing low mood and anxiety. Both cheerfulness and paranoia have a strong tendency to persist over time, increasing he probability of stable symptoms 18.

Previous work has shown that contextual precision diagnosis is highly sensitive to longitudinal development of phenotypes across definable stages; in that connection strength and connection variability between mental states differ in a predictable fashion across different stages of psychopathology 44. In addition, there is evidence that symptom circuit dynamics based on momentary assessment technology is sensitive to genetic variation and neural function 45–47, and can be used to predict dynamic transitions from a state of vulnerability to illness 48.

Contextual precision diagnosis is idiographic and sensitive to stages of psychopathology, replacing the need for nomothetic approaches that lack validity and practical utility 49. Finally, there is emerging evidence that the process of contextual precision diagnosis using ESM has therapeutic effects by itself 50–52.

CONCLUSIONS

Although it may be useful to retain some of the higher order syndromal groupings, such as common mental disorder and severe mental disorder, the focus of contextual precision diagnosis is on the individual, neutralizing the forces of stereotyping and treatment irrelevance. The summary presented above suggests that novel momentary assessment diagnostic systems delivering patient- and treatment-relevant information represent a welcome addition to the diagnostic toolbox in psychiatry.

References

- 1.Kapur S, Phillips AG, Insel TR. Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it? Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1174–9. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR, McGorry P, et al. Lessons learned from the psychosis high-risk state: towards a general staging model of prodromal intervention. Psychol Med. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000184. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borsboom D, Cramer AO, Schmittmann VD, et al. The small world of psychopathology. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kendler KS, Zachar P, Craver C. What kinds of things are psychiatric disorders? Psychol Med. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer AO, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HL, et al. Comorbidity: a network perspective. Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33:137–50. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09991567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton WW, Thara R, Federman B, et al. Structure and course of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:127–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140045005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentall RP, Wickham S, Shevlin M, et al. Do specific early-life adversities lead to specific symptoms of psychosis? A study from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:734–40. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer AO, Borsboom D, Aggen SH, et al. The pathoplasticity of dysphoric episodes: differential impact of stressful life events on the pattern of depressive symptom inter-correlations. Psychol Med. 2012;42:957–65. doi: 10.1017/S003329171100211X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III – the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:549–62. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivertsen B, Salo P, Mykletun A, et al. The bidirectional association between depression and insomnia: the HUNT study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:758–65. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182648619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman D, Pugh K, Vorontsova N, et al. Insomnia and paranoia. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:280–4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. A longitudinal etiologic model for symptoms of anxiety and depression in women. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2035–45. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, et al. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2001;31:189–95. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:409–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominguez MD, Saka MC, Lieb R, et al. Early expression of negative/disorganized symptoms predicting psychotic experiences and subsequent clinical psychosis: a 10-year study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1075–82. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09060883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maher BA. The relationship between delusions and hallucinations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8:179–83. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smeets F, Lataster T, Dominguez MD, et al. Evidence that onset of psychosis in the population reflects early hallucinatory experiences that through environmental risks and affective dysregulation become complicated by delusions. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:531–42. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wigman JT, Collip D, Wichers M, et al. Altered Transfer of Momentary Mental States (ATOMS) as the basic unit of psychosis liability in interaction with environment and emotions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominguez MD, Wichers M, Lieb R, et al. Evidence that onset of clinical psychosis is an outcome of progressively more persistent subclinical psychotic experiences: an 8-year cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:84–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wigman JT, Vollebergh WA, Raaijmakers QA, et al. The structure of the extended psychosis phenotype in early adolescence – a cross-sample replication. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:850–60. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackie CJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Conrod PJ. Developmental trajectories of psychotic-like experiences across adolescence: impact of victimization and substance use. Psychol Med. 2011;1:47–58. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wigman JT, van Winkel R, Jacobs N, et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental determinants of abnormal persistence of psychotic experiences in young adulthood. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B:546–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuepper R, van Os J, Lieb R, et al. Continued cannabis use and risk of incidence and persistence of psychotic symptoms: 10 year follow-up cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, et al. Experience sampling research in psychopathology: opening the black box of daily life. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1533–47. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, et al. Qgraph: network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yordanova J, Kolev V, Kirov R, et al. Comorbidity in the context of neural network properties. Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33:176–7. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X1000083X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser JP, van Os J, Portegijs PJ, et al. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lardinois M, Lataster T, Mengelers R, et al. Childhood trauma and increased stress sensitivity in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wichers M, Schrijvers D, Geschwind N, et al. Mechanisms of gene-environment interactions in depression: evidence that genes potentiate multiple sources of adversity. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1077–86. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, van Os J. Behavioural sensitization to daily life stress in psychosis. Psychol Med. 2005;35:733–41. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myin-Germeys I, Marcelis M, Krabbendam L, et al. Subtle fluctuations in psychotic phenomena as functional states of abnormal dopamine reactivity in individuals at risk. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collip D, Myin-Germeys I, Van Os J. Does the concept of "sensitization" provide a plausible mechanism for the putative link between the environment and schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:220–5. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:203–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs N, Rijsdijk F, Derom C, et al. Genes making one feel blue in the flow of daily life: a momentary assessment study of gene-stress interaction. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:201–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204919.15727.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menne-Lothmann C, Jacobs N, Derom C, et al. Genetic and environmental causes of individual differences in daily life positive affect and reward experience and its overlap with stress-sensitivity. Behav Genet. 2012;42:778–86. doi: 10.1007/s10519-012-9553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collip D, van Winkel R, Peerbooms O, et al. COMT Val158Met-stress interaction in psychosis: role of background psychosis risk. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:612–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peerbooms O, Rutten BP, Collip D, et al. Evidence that interactive effects of COMT and MTHFR moderate psychotic response to environmental stress. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:247–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Winkel R, Henquet C, Rosa A, et al. Evidence that the COMT(Val158Met) polymorphism moderates sensitivity to stress in psychosis: an experience-sampling study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:10–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simons CJ, Wichers M, Derom C, et al. Subtle gene-environment interactions driving paranoia in daily life. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wichers M, Aguilera M, Kenis G, et al. The catechol-O-methyl transferase Val158Met polymorphism and experience of reward in the flow of daily life. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3030–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wichers M, Kenis G, Jacobs N, et al. The psychology of psychiatric genetics: evidence that positive emotions in females moderate genetic sensitivity to social stress associated with the BDNF Val-sup-6-sup-6Met polymorphism. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:699–704. doi: 10.1037/a0012909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myin-Germeys I, Van Os J, Schwartz JE, et al. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1137–44. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lataster T, Wichers M, Jacobs N, et al. Does reactivity to stress cosegregate with subclinical psychosis? A general population twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wigman JTW, van Os J, Thiery E, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis revisited: towards a system of staging and profiling combining nomothetic and idiographic parameters of momentary mental states. PLoS One. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059559. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collip D, Myin-Germeys I, Wichers M, et al. FKBP5 as a possible moderator of the psychosis-inducing effects of childhood trauma. Br J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.115972. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marcelis M, Myin-Germeys I, Suckling J, et al. Cerebral tissue alterations and daily life stress experience in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:54–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wichers M, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, et al. Genetic risk of depression and stress-induced negative affect in daily life. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:218–23. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wichers M, Geschwind N, Jacobs N, et al. Transition from stress sensitivity to a depressive state: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:498–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGorry P, van Os J. Redeeming diagnosis in psychiatry: timing versus specificity. Lancet. 2013;381:343–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wichers M, Hartmann JA, Kramer IM, et al. Translating assessments of the film of daily life into person-tailored feedback interventions in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:402–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wichers M, Simons CJ, Kramer IM, et al. Momentary assessment technology as a tool to help patients with depression help themselves. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:262–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myin-Germeys I, Birchwood M, Kwapil T. From environment to therapy in psychosis: a real-world momentary assessment approach. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:244–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]