Towards Defining Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in Youth with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Using the Child Behavior Check List: A Controlled Study (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2013 Aug 8.

Published in final edited form as: Postgrad Med. 2011 Sep;123(5):50–59. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2011.09.2459

Abstract

Objective

Deficient emotional self regulation (DESR) is characterized by deficits in self-regulating the physiological arousal caused by strong emotions. We examined whether a unique profile of the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) would help identify DESR in children with Attention- Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Methods

Subjects were 197 children with and 224 without ADHD. We defined DESR if a child had an aggregate cut-off score of > 180 but < 210 on the Anxiety/Depression, Aggression, and Attention scales of the CBCL (CBCL-DESR). This profile was selected because of 1) its conceptual congruence with the clinical concept of DESR and 2) because its extreme (>210) form had been previously associated with severe forms of mood and behavioral dysregulation in children with ADHD. All subjects were comprehensively assessed with structured diagnostic interviews and a wide range of functional measures.

Results

Forty four percent of children with ADHD had a positive CBCL- DESR profile vs. 2% of controls (p<0.001). The CBCL-DESR profile was associated with elevated rates of anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders, as well as significantly more impairments in emotional and interpersonal functioning.

Conclusions

The CBCL-DESR profile helped identify a subgroup of ADHD children with a psychopathological and functional profile consistent with the clinical concept of DESR.

Keywords: Attention- deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, Affective symptoms, Severity of illness index, youth

INTRODUCTION

Although Attention- Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has long been conceptualized as a disorder of deficient self regulation, 1 deficient emotional self regulation (DESR) has only recently been the focus of scientific investigation. DESR refers to 1) deficits in self-regulating the physiological arousal caused by strong emotions; 2) difficulties inhibiting inappropriate behavior in response to either positive or negative emotions; 3) problems refocusing attention from strong emotions and 4) disorganization of coordinated behavior in response to emotional activation. 2 Clinically, DESR traits include low frustration tolerance, impatience, quickness to anger, and being easily excited to emotional reactions. Although these traits may be a source of significant morbidity, there has been a paucity of research on the subject, 2–6 and uncertainties remain on how to best measure it.

One approach to identify DESR in children with ADHD, could be through the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), an empirically derived, paper and pencil scale with excellent psychometric properties. A particular profile of the CBCL consisting of very abnormal (2SDs) scores on the Anxiety/Depression, Aggression, and Attention scales of the CBCL has been postulated to measure severe forms of dysregulated mood and behavior associated with pediatric bipolar disorder, 7–9 with high levels of morbidity and dysfunction including psychiatric hospitalization and suicidality. Because these scales reflect intense emotions (Anxiety/Depression scale), aggression (Aggression scale) and impulsive behavior (Attention scale), a profile of very high scores in these scale (>210 [2SDs]) has been named the CBCL-juvenile bipolar disorder profile by some 7–9 and, as a continuous measure, the CBCL-Dysregulation Profile (CBCL-DP) by others. 10–12, 13 We reasoned that an intermediate profile comprising of intermediate (>1 and <2 SDs) elevations of these scales could adequately capture the clinical construct of DESR.

The study of DESR is clinically urgent for several reasons. If DESR symptoms are not identified by clinicians, they cannot be evaluated appropriately and incorporated into treatment plans. Of equal importance, the symptoms of DESR should not be confused with the emotional symptoms of bipolar disorder. To do so would increase the misdiagnosis of mood disorders and lead to inappropriate treatment. This creates a difficult differential diagnostic issue because although ADHD is a risk factor for bipolar disorder, 14, 15 misdiagnosis will occur if DESR is mistaken for the abnormal mood associated with bipolar disorder and vice versa. DESR differs from the persistent and severe aggressive irritability often seen in pediatric bipolar disorder. 16 Unlike DESR, the abnormal mood of bipolar disorder is not defined by poor self-regulation and includes features that are not part of DESR (e.g., the other mood criteria in DSM-IV).

The main aim of this study was to assess whether a unique profile in CBCL characterized by intermediate elevation in the Anxiety/depression, Aggression and Attention scales could be used to help identify DESR in children with ADHD. To this end we analyzed data from two identically designed large scale, controlled studies of well-characterized boys and girls with and without ADHD. We categorically defined DESR if a child had an aggregate cutoff score of > 180 [1 SD] but less than 210 (2SD) on the Anxiety/Depression, Aggression, and Attention scales of the CBCL (CBCL-DESR). We hypothesized that the CBCL-DESR profile would be overrepresented in children with ADHD and will be associated with high levels of morbidity and dysfunction beyond those predicted by ADHD status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed study methodology has been previously described. 17, 18 Briefly, subjects were derived from two identically designed longitudinal case-control family studies of ADHD. These studies recruited male and female probands aged 6–18 years with (n=140 boys, n=140 girls) and without (n=120 boys, n=122 girls) ADHD ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric clinics and their siblings. Potential subjects were excluded if they had been adopted, or if their nuclear family was not available for study. We also excluded potential subjects if they had major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a Full Scale IQ less than 80. Diagnoses of subjects less than 12 years of age were based on indirect interviews with the mothers. Subjects between 12 and 17 years of age had indirect and direct interviews and a diagnosis was considered positive if either of the interviewees endorsed the disorder. Parents provided consent for offspring under the age of 18. Children and adolescents provided written assent to participate. The human research committee at Massachusetts General Hospital approved this study.

Psychiatric assessments relied on the epidemiologic version of the Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for Children (Kiddie SADSE). 19 The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology and were extensively trained and supervised. Based on 500 interviews the median kappa coefficient between a trained rater and an experience clinician was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: ADHD (0.88), CD (1.0), major depression (1.0), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.0), agoraphobia (1.0), panic (0.95) and substance use disorder (1.0). We considered a diagnosis present if DSM III-R diagnostic criteria were unequivocally met.

A committee of board-certified child and adult psychiatrists who were blind to the subject’s ADHD status, referral source, and all other data resolved diagnostic uncertainties. Diagnoses presented for review were considered positive only when the committee determined that diagnostic criteria were met to a clinically meaningful degree. We estimated the reliability of the diagnostic review process by computing kappa coefficients of agreement for clinician reviewers. For these diagnoses, the median reliability between individual clinicians and the review committee assigned diagnoses was 0.87. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: ADHD (1.0), CD (1.0), major depression (1.0), mania (0.78), separation anxiety (0.89), agoraphobia (0.80), panic (0.77) and substance use disorder (1.0). All assessment personnel were blind to proband diagnosis (ADHD or control) and ascertainment site (psychiatric or pediatric).

Mothers completed the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA). 20 The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) 21 provided dimensional measures of child syndromes. Family conflict was defined using the Moos Family Environment Scale (FES). 22 Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using the 5-point Hollingshead scale. 23 The interview also contained questions pertaining to school functioning.

Defining DESR Using Scores of the CBCL

A binary definition of deficient emotional self-regulation (DESR) was defined as positive if a subject’s sum of the attention, aggression, and anxious/depressed CBCL scales (i.e., CBCL-DESR) was > 180 (> 60 on average on each scale) but <210 (average t-score of >60<70 on each scale), a cut-off point previously used to define a more extreme from of emotional dysregulation associated with pediatric bipolar disorder (the CBCL Pediatric Bipolar Profile). 7–9

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made between Controls without DESR (Controls), ADHD subjects without DESR (ADHD), and ADHD subjects with CBCL-DESR (ADHD+DESR). Subjects with a CBCL-score of 210 on the A-A-A scales or higher (average t-score of >70 on each scale) were excluded. Linear, logistic, negative binomial, or ordered logistic regression was used depending on the distribution of the outcome measure. Demographic confounders were controlled for in all models. All tests were two-tailed and alpha was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Rates of DESR in Children with and without ADHD

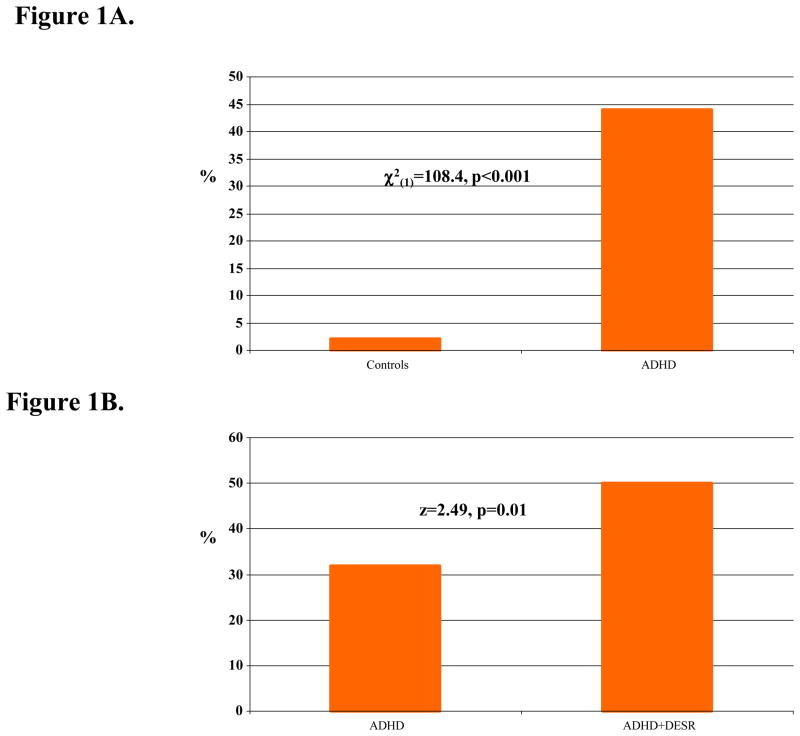

ADHD children had a significantly higher rate of the CBCL-DESR profile compared to Controls (44% versus 2%, χ2(1)=108.4, p<0.001). Comparisons were made between Controls (N=224), ADHD subjects without DESR (ADHD, N=111), and ADHD subjects with CBCL-DESR (ADHD+CBCL-DESR, N=86).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. There were small but statistically significant differences in age. The ADHD+CBCL-DESR group was younger than Controls, thus we controlled further analyses by age.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Controls (N=224) | ADHD (N=111) | ADHD+DESR (N=86) | Test statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.9 ± 3.4 | 11.2 ± 3.2 | 10.7 ± 3.0a | F(2,418)=5.03 | 0.007 |

| Male | 116 (52) | 61 (55) | 48 (56) | χ2(2)=0.54 | 0.76 |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | χ2(2)=2.77 | 0.25 |

Impact of DESR on ADHD Characteristics

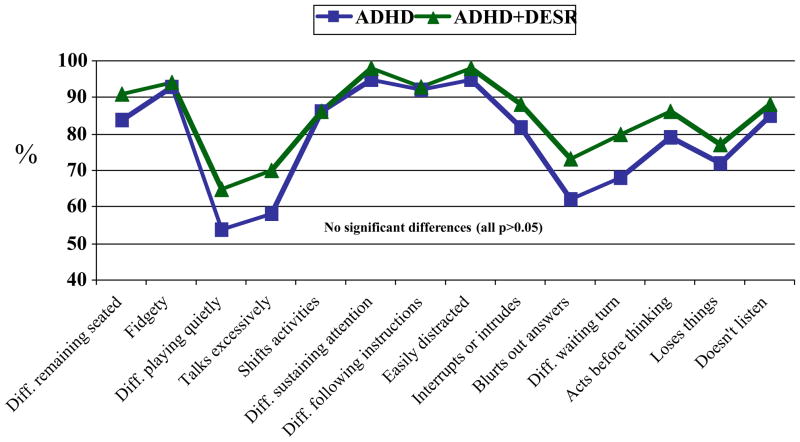

ADHD subjects with and without CBCL-DESR had similar ages of ADHD onset, duration of ADHD, and total ADHD symptoms (Table 2). However, ADHD+CBCL-DESR subjects showed significantly greater ADHD-associated impairment (Fig 1 panel B). ADHD subjects with and without CBCL-DESR did not differ on rates of individual ADHD symptoms (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of ADHD

| ADHD (N=111) | ADHD+DESR (N=86) | Test statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 3.1 ± 2.4 | t(194)=−0.36 | 0.83 |

| Duration | 7.6 ± 3.9 | 7.2 ± 3.8 | t(194)=0.20 | 0.69 |

| Total symptoms | 11.1 ± 2.0 | 11.9 ± 1.8 | z=1.68 | 0.09 |

| Severe impairment | 35 (32) | 43 (50) | z=2.49 | 0.01 |

| Moderate/ severe impairment | 99 (89) | 84 (98) | z=2.04 | 0.04 |

Figure 1.

A. Rates of deficient emotional self-regulation (DESR, sum of CBCL attention, aggression, and anxious/depressed t-scores ≥180 and <210); (B) Percent of subjects with ADHD-associated severe impairment

Figure 2.

Attention- Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms

Impact of DESR on Psychopathology

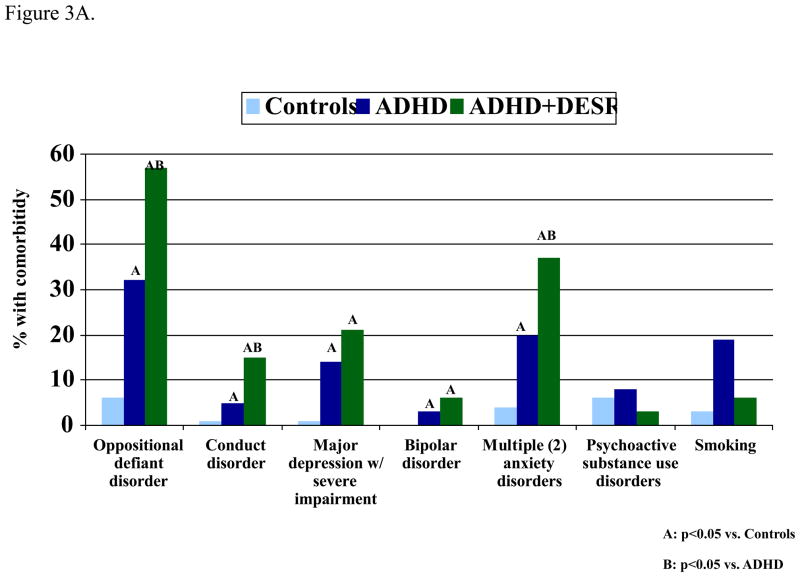

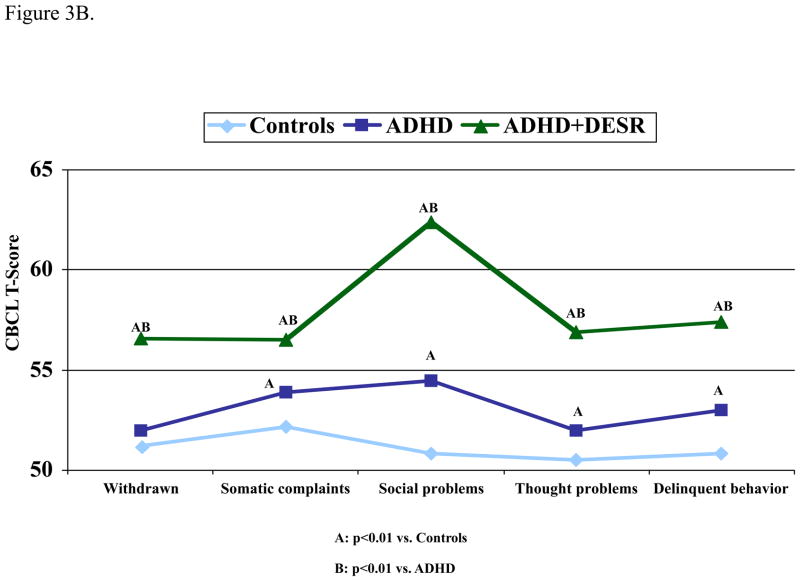

As shown in Fig 3A, rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders differed significantly among the three groups for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), major depression (MDD), bipolar disorder (BPD), and multiple (≥2) anxiety disorders. Among ADHD patients, DESR predicted increased rates of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and multiple (≥2) anxiety disorders (Figure 3A), but not major depression bipolar disorder or substance use disorders (FIG 3A). Consistent with the comorbidity findings DESR was associated with more impaired scores in all other CBCL clinical scales (excluding those used to define DESR) (Fig 3B). Controlling for comorbid ODD, CD, and multiple anxiety disorders, the ADHD+DESR group still had significantly more impaired scores on these CBCL clinical scales compared to the ADHD group.

Figure 3.

DESR and psychopathology (A) Comorbid disorders; (B) Other Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) scales

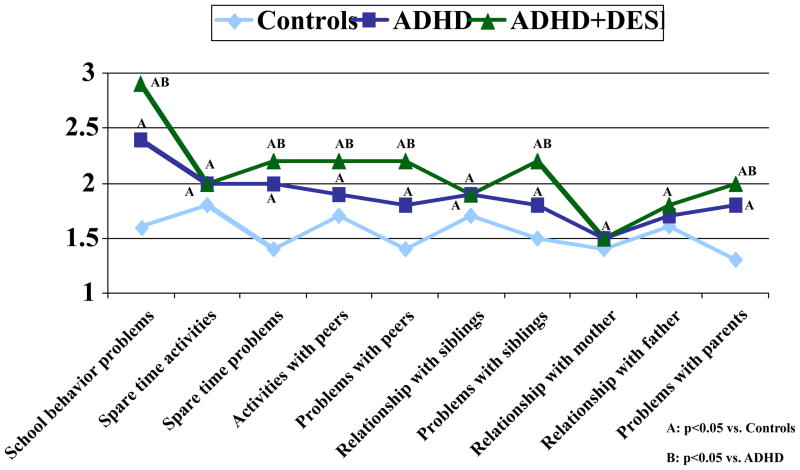

Impact of CBCL-DESR on Social Functioning

As shown in Figure 4, there was dose response association in the majority of items assessed in the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA). Social functioning was least impaired in Controls, intermediate in ADHD, and most impaired in ADHD+CBCL-DESR. Controlling for comorbid ODD, CD, and multiple anxiety disorders, SAICA items school behavior problems, activities with peers, and problems with peers remained significantly different between the ADHD and ADHD+CBCL-DESR groups.

Figure 4.

Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA)

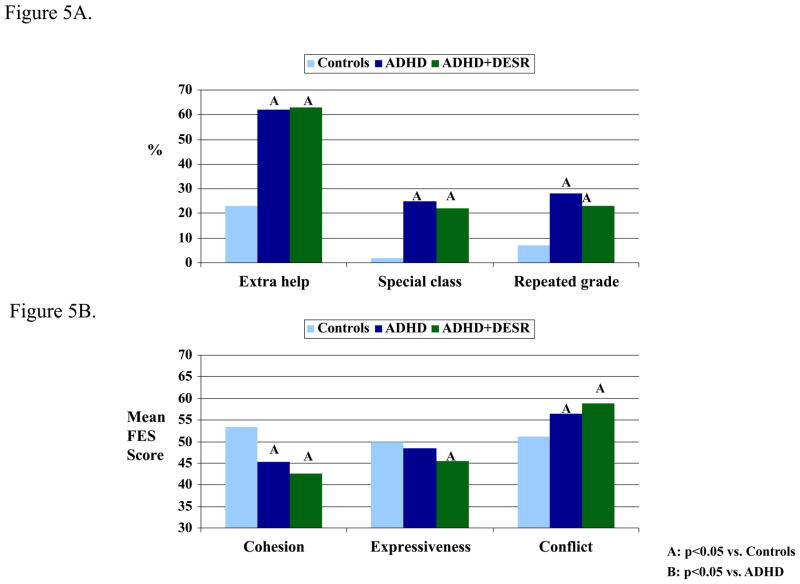

School and Family Functioning and Treatment History

Although ADHD was associated with more impaired school and family functioning than controls, the two ADHD groups did not differ in measures of school (Fig 5A) or family functioning (Fig 5B). Subjects with ADHD+CBCL-DESR were more likely to be treated for ADHD compared to the ADHD group (Table 3). Although ADHD+CBCL-DESR subjects had a higher rate of combined counseling and pharmacotherapy, they were not at higher risk for requiring psychiatric hospitalization.

Figure 5.

School and family functioning; (A) School functioning; (B) Family Environment Scale (FES)

Table 3.

| Table 3A. ADHD Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD (N=111) | ADHD+DESR (N=86) | Test statistic | p-value | |

| None | 25 (23) | 8 (9) | z=−2.41 | 0.02 |

| Counseling | 7 (6) | 7 (8) | z=0.49 | 0.63 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 30 (27) | 26 (30) | z=0.48 | 0.63 |

| Counseling + Pharmacotherapy | 48 (43) | 45 (52) | z=1.29 | 0.20 |

| Hospitalization | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | Fisher’s exact | 1.00 |

| Table 3B. Treatment for any Psychiatric Disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N=224) | ADHD (N=111) | ADHD+DESR (N=86) | Test statistic | p-value | |

| None | 99 (44) | 12 (11)a | 3 (3)a | χ2(2)=51.38 | <0.001 |

| Counseling | 42 (19) | 18 (16)a | 11 (13)a | χ2(2)=0.84 | 0.66 |

| Pharmacotherapy | 1 (0) | 31 (28)a | 23 (27)a | χ2(2)=19.00 | <0.001 |

| Counseling + Pharmacotherapy | 1 (0) | 46 (41)a | 48 (56)ab | χ2(2)=31.37 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization | 0 (0) | 4 (4)a | 1 (1) | Fisher’s exact | 0.01 |

DISCUSSION

Our a priori definition of DESR based on moderate (>1 and <2 SDs) elevation of the Anxiety/depression, Aggression and Attention scales of the CBCL (CBCL-DESR) identified a clinically meaningful subgroup of ADHD children at high risk for morbidity and dysfunction consistent with current conceptualizations of DESR. In fact, 44% of children with ADHD met criteria for our definition of DESR based on the CBCL compared with only 2% of control subjects. The CBCL-DESR profile was associated with higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity with anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders and with significantly more impaired ratings in most domains of social function evaluated by the SAICA. These findings suggest that the CBCL-DESR profile can help identify a clinically meaningful subgroup of children with ADHD with associated deficits consistent with current clinical conceptualizations of deficits in emotional regulation worthy of further investigation.

The 44% rate of CBCL-DESR profile identified in our sample of ADHD children is highly consistent with recent findings in adults with ADHD. 3, 4 This latter study using items from the Current Behavior Scale congruent with clinical conceptualizations of DESR, identified DESR in 55% of adults with ADHD. As we found in our pediatric sample, DESR in this adult ADHD study was also associated with higher rates of psychopathology and dysfunction. 3, 4

Our findings that children with ADHD with the CBCL-DESR profile were at significantly increased risks for disruptive behavior and anxiety disorders but not for depression and bipolar disorder stand in contrast with findings of increased risks for these mood disorders associated with the CBCL-Juvenile Bipolar profile. This latter profile requires very abnormal (2SD) scores on the same scales of Anxiety/Depression, Aggression, and Attention of the CBCL used to define the CBCL-DESR profile but with more moderate (>1 and < 2 SDs) scores. These non-overlapping CBCL profile findings between the high (2SD) and the intermediate (1SD) (used to define DESR) support the hypotheses that these mutually exclusive profiles identify different clinical entities with the severe profile likely identifying the extreme mood dysregulation associated with mood disorder while the intermediate one being limited to deficient emotional self-regulation.

While both DESR and mood disorders involve emotional dysregulation, these constructs are substantially different clinically. The cardinal feature of mood disorders is the experience of strong emotions, not their self-regulation, 24 the hallmark of DESR. Children who fulfilled the CBCL-DESR criteria were not more likely to have bipolar disorder or major depression or to have been hospitalized than other children with ADHD. In this regard, our data support the utility of the CBCL in defining DESR as a substantially different clinical entity than the CBCL-Juvenile Bipolar profile used to identify children at high risk for pediatric bipolar disorder. In fact, a comprehensive literature review by Barkley et al. 2 documents numerous studies in which children and adults with ADHD are highly likely to manifest DESR characterized by “low frustration tolerance, impatience, quickness to anger, and being easily excited to emotional reactions more generally”.

We also found that ADHD children with the CBCL-DESR profile were at significantly increased risk for impaired social functioning beyond what was observed in other ADHD youth. Scores for most of the individual items on the SAICA as well as the social problems scale of the CBCL were significantly more impaired in ADHD+CBCL-DESR youth compared with other ADHD youth. These included worse functioning with peers, siblings and parents in all four major role areas: school, spare time, peer relations, and home life. These findings are consistent with those of Whalen and Henker’s 25 who found that emotional dysregulation in ADHD children disrupted the smoothness, reciprocity, and cooperative activities involved in peer relationships and with Barkley et al.’s 2 suggestion that DESR might account for a significant portion of the prominent social dysfunction documented in ADHD. These authors speculated that DESR may trigger negative reactions from peers, siblings and parents which, in turn, might lead to further poor social responses in the affected child. 25

In contrast, we did not find that the CBCL-DESR profile increased the risk for added impairments in family and school (academic) functioning beyond those predicted by ADHD. These findings are not consistent with those reported by Barkley and Fischer 2 in their long term longitudinal follow up study of ADHD children grown up that found that, after accounting for ADHD, DESR independently contributed to impairments in occupational and educational, outcomes in young adult years. More work needs to be done to examine the longitudinal impact of CBCL-DESR on family and educational outcomes in children with ADHD grown up.

Because the CBCL-DESR profile is a continuous and morbid phenotype that cuts across several psychiatric disorders, it represents an ideal target for pathophysiological, neurobiological and therapeutic research within and without the context of ADHD. Such a phenotype is consistent with the recently outlined research domain criteria (RDoC) proposed by the NIMH (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-funding/nimh-research-domain-criteria-rdoc.shtml). RDoC are conceived as dimensional phenotypes ranging from normal to abnormal that cut across current diagnostic boundaries and use different levels of analysis. Such dimensional phenotypes are thought to be central to understanding the underlying psychopathology of normal and abnormal brain function and to facilitate critical research on determining the underlying genetic influences as well as neural networks.

Our findings need to be viewed in light of some methodological limitations. Our definition of emotional dysregulation relied on elevations in three CBCL clinical scales (A-A-A). Others have used this scale without cutoffs to measure dysregulated mood, attention and behavior pathology across DSM-IV diagnoses. 11 Although we selected the CBCL-DESR profile from ongoing conceptualizations of DESR in the literature (most fully articulated by Barkley) 2 indexing deficits in self-regulating cognition and inhibiting behavior caused by strong emotions, we do not know whether our results would be replicated if other methods are used to define DESR.

For example, Gioia reported that children with ADHD had higher ratings on the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) 26 Emotional Control subscale compared with healthy children. However, since these authors did not report correlations of their BRIEF-defined DESR (beyond impulsivity), it is unclear whether the BRIEF-Emotional Control Scale captures the same phenomenology as the CBCL-DESR profile. On the other hand, the validity of our construct of CBCL-DESR is supported by 1) Face Validity, the consistency of the constituent symptoms with other definitions of DESR 2) its expression across a wide range of comorbid disorders and elevations of clinical scales and 3) its association with significant impairments beyond those accounted for by ADHD. Also, it is reassuring that our results are similar to what we reported as the correlates of DESR in adults with ADHD, which used a different method to assess DESR symptoms. 3, 4 Nevertheless, further research is needed to evaluate other definitions of DESR to determine its optimal definition. Because our sample was clinically referred and primarily Caucasian, our findings may not generalize to community samples and other ethnic groups.

CONCLUSION

These findings indicate that a unique profile of the CBCL consistent of intermediate (>1 and <2 SDs) scores on Anxiety/Depression, Attention and Aggression can help identify a clinically meaningful subgroup of children with ADHD at high risk for more impaired social and emotional adjustment than other children with ADHD. Because this profile identified children with dysregulated mood, anxiety, aggression, and impulsivity, our findings suggests that the CBCL-DESR may aid in the identification of children with deficient emotional regulation within and without the context of ADHD. More work is needed to further evaluate this and other definitions of DESR in clinical and investigational studies of children with ADHD.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by grants to J. Biederman from the National Institute of Health (R01 HD36317 R01 MH50657) and to T. Spencer from Shire Pharmaceuticals and the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Research Council Fund.

Role of Study Sponsor: The study sponsor had no role in the study design or conduct; collection, management, preparation, or analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Thomas Spencer has received research support from, has been a speaker for or on a speaker bureau or has been an Advisor or on an Advisory Board of the following sources: Shire Laboratories, Inc, Eli Lilly & Company, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Janssen Pharmaceutical, McNeil Pharmaceutical, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Cephalon, Pfizer, the National Institute of Mental Health and royalties on adult ADHD scales (research support).

In the past year, Dr. Faraone received consulting fees and was on Advisory Boards for Shire Development and received research support from Shire and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In previous years, he received consulting fees or was on Advisory Boards or participated in continuing medical education programs sponsored by: Shire, McNeil, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. In previous years he received research support from Eli Lilly, Shire, Pfizer and the NIH. Dr. Faraone receives royalties from a book published by Guilford Press: Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health.

Dr. Surman has received research support from Abbott, Alza, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, the Hilda and Preston Davis Foundation, McNeil, Merck, New River, National Institutes of Health, Organon, Pfizer, Shire, and Takeda; has received support from Janssen-Ortho, McNeil, Novartis, and Shire for speaking and other educational activities; and has been a consultant/advisor for McNeil, Shire, and Takeda. Dr. Surman has also received honoraria from Reed Medical Education (a logistics collaborator for the MGH Psychiatry Academy). Commercial entities supporting the MGH Psychiatry Academy are listed on the Academy’s Web site, www.mghcme.org.

Dr. Janet Wozniak, M.D. is the author of, “Is Your Child Bipolar” published May 2008, Bantam Books. Speaker: Primedia/MGH Psychiatry Academy. Research Support: McNeil, Shire, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson. Her spouse_, John Winkelman MD, PhD: Speakers Bureau:_ Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor_. Consultant/Advisory Board:_ Covance, GlaxoSmithKline, Impax Laboratories, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Neurogen, Pfizer, UCB, Zeo Inc. Research Support: GlaxoSmithKline, Sepracor.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: Elminda, Janssen, McNeil, Next Wave Pharmaceuticals, and Shire. In 2011, Dr. Joseph Biederman gave a single unpaid talk for Juste Pharmaceutical Spain, and received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course. He also received an honorarium from Cambridge University Press for a chapter publication. Dr. Biederman received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Eli Lilly, Shire and AstraZeneca; these royalties are paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH. In 2010, Dr. Joseph Biederman received a speaker’s fee from a single talk given at Fundación Dr. Manuel Camelo A.C. in Monterrey Mexico. Dr. Biederman provided single consultations for Shionogi Pharma Inc. and Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc.; the honoraria for these consultations were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at the MGH. Dr. Biederman received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course. In 2009, Dr. Joseph Biederman received a speaker’s fee from the following sources: Fundacion Areces (Spain), Medice Pharmaceuticals (Germany) and the Spanish Child Psychiatry Association. In previous years, Dr. Joseph Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: Abbott, Alza, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltech, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, Forest, Glaxo, Gliatech, Janssen, McNeil, Merck, NARSAD, NIDA, New River, NICHD, NIMH, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pharmacia, The Prechter Foundation, Shire, The Stanley Foundation, UCB Pharma, Inc. and Wyeth.

Carter Petty, Allison Clarke, Holly Batchelder have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull. 1997;121(1):65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkley RA. Deficient Emotional Self-Regulation: A Core Component of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 2010;1(2):5–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surman CBH, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Miller CA, Faraone SV. Understanding Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Controlled Study. American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; New York. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surman C, Biederman J, Spencer T, Miller C, Faraone SV. Understanding Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Controlled Study. The Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. doi: 10.1007/s12402-012-0100-8. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reimherr FW, Marchant BK, Williams ED, Strong RE, Halls C, Soni P. Personality disorders in ADHD Part 3: Personality disorder, social adjustment, and their relation to dimensions of adult ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22(2):103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen SA, Rosen LA. Emotional reactivity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2004;8(2):53–61. doi: 10.1177/108705470400800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, et al. The child behavior checklist-pediatric bipolar disorder profile predicts a subsequent diagnosis of bipolar disorder and associated impairments in ADHD youth growing up: a longitudinal analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(5):732–740. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mick E, Biederman J, Pandina G, Faraone SV. A preliminary meta-analysis of the child behavior checklist in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(11):1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faraone SV, Althoff RR, Hudziak JJ, Monuteaux MC, Biederman J. The CBCL predicts DSM bipolar disorder in children: A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Bipolar Disorders. 2005;7(6):518–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holtmann M, Buchmann AF, Esser G, Schmidt MH, Banaschewski T, Laucht M. The Child Behavior Checklist-Dysregulation Profile predicts substance use, suicidality, and functional impairment: a longitudinal analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;52(2):139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayer L, Althoff R, Ivanova M, et al. Child Behavior Checklist Juvenile Bipolar Disorder (CBCL-JBD) and CBCL Posttraumatic Stress Problems (CBCL-PTSP) scales are measures of a single dysregulatory syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(10):1291–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Ayer LA, Hudziak JJ. Cross-informant agreement of the dysregulation profile of the child behavior checklist. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(3):550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Althoff RR, Ayer LA, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ. Assessment of dysregulated children using the child behavior checklist: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(3):609–617. doi: 10.1037/a0019699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biederman J, Petty CR, Byrne D, Wong P, Wozniak J, Faraone SV. Risk for switch from unipolar to bipolar disorder in youth with ADHD: A long term prospective controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2009;119(1–3):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Monuteaux M, Coville A, Biederman J. A controlled family study of children with DSM-IV bipolar-I disorder and psychiatric co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2010;40(7):1079–1088. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kwon A, et al. How cardinal are cardinal symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder? An examination of clinical correlates. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(7):583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(8):966–975. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):437–446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050073012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orvaschel H. Psychiatric interviews suitable for use in research with children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):737–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John K, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA, Warner V. The social adjustment inventory for children and adolescents (SAICA): testing of a new semistructured interview. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26(6):898–911. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198726060-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and the 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moos RH, Moos BS. Manual for the Family Environment Scale. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven: Yale Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen PJ, Epstein JN. A Pilot Study of Ecological Momentary Assessment of Emotion Dysregulation in Children. Journal of ADHD and Related Disorders. 2010;1(4):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whalen CK, Henker B. The social profile of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1992;1(2):395–410. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Brief behavior rating inventory of executive function: Manual. Lutz, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]