The cytoplasm of living cells behaves as a poroelastic material (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Feb 17.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Mater. 2013 Jan 6;12(3):253–261. doi: 10.1038/nmat3517

Abstract

The cytoplasm is the largest part of the cell by volume and hence its rheology sets the rate at which cellular shape changes can occur. Recent experimental evidence suggests that cytoplasmic rheology can be described by a poroelastic model, in which the cytoplasm is treated as a biphasic material consisting of a porous elastic solid meshwork (cytoskeleton, organelles, macromolecules) bathed in an interstitial fluid (cytosol). In this picture, the rate of cellular deformation is limited by the rate at which intracellular water can redistribute within the cytoplasm. However, direct supporting evidence for the model is lacking. Here we directly validate the poroelastic model to explain cellular rheology at physiologically relevant timescales using microindentation tests in conjunction with mechanical, chemical and genetic treatments. Our results show that water redistribution through the solid phase of the cytoplasm (cytoskeleton and macromolecular crowders) plays a fundamental role in setting cellular rheology**.**

Keywords: Cell mechanics, poroelasticity, viscoelasticity, microstructure

One of the most striking features of eukaryotic cells is their capacity to change shape in response to environmental or intrinsic cues driven primarily by their actomyosin cytoskeleton. During gross changes in cell shape, induced either by intrinsic switches in cell behaviour (e.g. cell rounding, cytokinesis, cell spreading, or cell movement) or by extrinsic stress application during normal organ function, the maximal rate at which shape change can occur is dictated by the rate at which the cytoplasm can be deformed because it forms the largest part of the cell by volume. Furthermore, it is widely recognised that cells detect, react, and adapt to external mechanical stresses. However, in the absence of an in depth understanding of cell rheology, the transduction of external stresses into intracellular mechanical changes is poorly understood making the identification of the physical parameters that are detected biochemically purely speculative1.

Living cells are complex materials displaying a high degree of structural hierarchy and heterogeneity coupled with active biochemical processes that constantly remodel their internal structure. Therefore, perhaps unsurprisingly, they display an astonishing variety of rheological behaviours depending on amplitude, frequency and spatial location of loading1,2. Over the years, a rich phenomenology of rheological behaviours has been uncovered in cells such as scale-free power law rheology, strain stiffening, anomalous diffusion, and rejuvenation (reviewed in 1-4). Several theoretical models explain these observed behaviours but finding a unifying theory has been difficult because different microrheological measurement techniques excite different modes of relaxation1. These rheological models range from those that treat the cytoplasm as a single phase material whose rheology is described using networks of spring and dashpots5, to the sophisticated soft glassy rheology (SGR) models that describe cells as being akin to soft glassy materials close to a glass transition6,7; in either case, the underlying geometrical and biophysical phenomena remain poorly defined1,4. Furthermore, none of the models proposed account for dilatational changes in the multiphase material that is the cytoplasm. Yet, these volumetric deformations are ubiquitous in the context of phenomena such as blebbing, cell oscillations or cell movement8,9, and in gels of purified cytoskeletal proteins10 whose macroscopic rheological properties depend on the gel structural parameters and its interaction with an interstitial fluid11-13. Any unified theoretical framework that aims to capture the rheological behaviours of cells and link these to cellular structural and biological parameters must account for both the shear and dilatational effects seen in cell mechanics as well as account for the role of crowding and active processes in cells.

The flow of water plays a critical part in such processes. Recent experiments suggest that pressure equilibrates slowly within cells (~10s)8,14,15 giving rise to intracellular flows of cytosol9,16 that cells may exploit to create lamellipodial protrusions9 or blebs8 for locomotion17. Furthermore, the resistance to water flow through the soft porous structure serves to slow motion in a simple and ubiquitous way that does not depend on the details of structural viscous dissipation in the cytoplasmic network. Based on these observations, a coarse-grained biphasic description of the cytoplasm as a porous elastic solid meshwork bathed in an interstitial fluid (e.g. poroelasticity18 or the two-fluid model19) has been proposed as a minimal framework for capturing the essence of cytoplasmic rheology8,15,20. In the framework of poroelasticity, coarse graining of the physical parameters dictating cellular rheology accounts for the effects of interstitial fluid and related volume changes, macromolecular crowding and a cytoskeletal network8,15,21, consistent with the rheological properties of the cell on the time-scales needed for redistribution of intracellular fluids in response to localised deformation. The response of cells to deformation then depends only on the poroelastic diffusion constant Dp, with larger values corresponding to more rapid stress relaxations. This single parameter scales as Dp ~ E ξ2/μ with E the drained elastic modulus of the solid matrix, ξ the radius of pores in the solid matrix, and μ the viscosity of the cytosol (see supplementary information), allowing changes in cellular rheology to be predicted in response to changes in E, ξ, and μ.

Here, we probed the contribution of intracellular water redistribution to cellular rheology at time-scales relevant to cell physiology (up to 10s) and examined the relative importance of crowding and the cytoskeleton in determining cell rheology. To confirm the generality of our findings across cell types, our experiments examined HT1080 fibrosarcoma, HeLa cervical cancer cells, and MDCK epithelial cells.

RESULTS

Cellular force-relaxation at short time-scales is poroelastic

First, we established the experimental conditions under which water redistribution within the cytoplasm might contribute to force-relaxation. In our experiments (Fig. 1A), following rapid indentation with an AFM cantilever (3.5-6nN applied during a rise time _tr_~35ms resulting in _δ_~1μm cellular indentation), force decreased by ~35% whereas indentation depth only increased by less than ~5%, showing that our experiments measure force-relaxation under approximately constant applied strain (Fig. 1B,C). Relaxation in poroelastic materials is due to water movement out of the porous matrix in the compressed region. The time-scale for water movement is tp~L2/Dp (L is the length-scale associated with indentation22: L∼Rδ with R the radius of the indenter) and therefore poroelastic relaxation contributes significantly if the rate of force application is faster than the rate of water efflux: tr<<tp. Previous experiments estimated _Dp_~1-100 μm2.s−1 in cells8,15 yielding a characteristic poroelastic time of _tp~_0.1-10s, far longer than tr. Hence, if intracellular water redistribution is important for cell rheology, force-relaxations curves should display characteristic poroelastic signatures for times up to _tp~_0.1-10s.

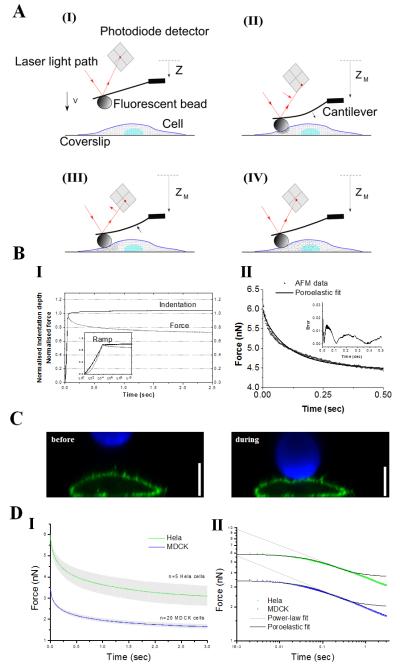

FIGURE 1. Experimental setup.

(A) Schematic diagram of the experiment. (A-I) The AFM cantilever is lowered towards the cell surface with a high approach velocity Vapproach ~30 μm.s−1. (A-II) Upon contacting the cell surface, the cantilever bends and the bead starts indenting the cytoplasm. Once the target force FM is reached, the movement of the piezoelectric ceramic is stopped at ZM. The bending of the cantilever reaches its maximum. This rapid force application causes a sudden increase in the local stress and pressure inside the cell. (A-III) and (A-IV) Over time, the cytosol in the compressed area redistributes inside the cell and the pore pressure dissipates. Strain resulting from the local application of force propagates through the elastic meshwork and at equilibrium, the applied force is entirely balanced by cellular elasticity. Indentation (I-II) allows the estimation of elastic properties and relaxation (III-IV) allows for estimation of the time-dependent mechanical properties. In all panels, the red line shows the light path of the laser reflected on the cantilever, red arrows show the change in direction of the laser beam, black arrows show the direction of bending of the cantilever, and the small dots represent the propagation of strain within the cell. (B) (I) Temporal evolution of the indentation depth (black) and measured force (grey) in response to AFM microindentation normalized to values when target force is reached. Inset: approach phase from which the elasticity is calculated (grey curve). The total approach lasts ~35 ms. (II) The first 0.5 s of experimental force-relaxation curves were fitted with the poroelastic model (black line). Inset: percentage error defined as |FAFM - Ffit|/FAFM. (C) Z-x confocal image of a HeLa cell expressing PH-PLCδ1-GFP (a membrane marker) corresponding to phases (I) and (IV) of the experiment described in A. The fluorescent bead attached to the cantilever is shown in blue and the cell membrane is shown in green. Scale bar =10 μm. (D) (I) Population averaged force-relaxation curves for HeLa cells (green) and MDCK cells (blue) for target indentation depths of 1.45μm for HeLa cells and 1.75μm for MDCK cells. Curves are averages of n=5 HeLa cells and n=20 MDCK cells. The grey shaded area around the average relaxation curves represents the standard deviation of the data. (II) Population averaged force-relaxation curves for HeLa cells (green) and MDCK cells (blue) from D-I plotted in a log-log scale. For both cell types, experimental force-relaxation was fitted with poroelastic (black solid line) and power law relaxations (grey solid line).

Population averaged force-relaxation curves showed similar trends for both HeLa and MDCK cells with a rapid decay in the first 0.5s followed by slower decay afterwards (Fig. 1D-I). In Fig. 1D-II, we see that force-relaxation clearly displayed two separate regimes: a plateau lasting ~0.1-0.2s followed by a transition to a linear regime (Fig. 1D-II). Hence, at short time-scales, cellular force-relaxation does not follow simple power laws. Comparison with force-relaxation curves acquired on physical hydrogels22,23, which display a plateau at short time-scales followed by a transition to a second plateau at longer time-scales (Fig. S3A-B), suggests that the initial plateau observed in cellular force-relaxation may correspond to poroelastic behaviour. Indeed poroelastic models fitted the force-relaxation data well for short times (<0.5s); whereas power law models were applicable for times longer than ~0.1-0.2s (Fig. 1D-II). Finally, when force-relaxation curves acquired for different indentation depths on cells were renormalized for force and rescaled with a time-scale dependent on indentation depth, all experimental curves collapsed onto a single master curve for short time-scales, confirming that the initial dynamics of cellular force-relaxation are due to intracellular water flow (Fig. S1-3, supplementary results). Together, these data suggested that for time-scales shorter than ~0.5s, intracellular water redistribution contributed strongly to force-relaxation, consistent with the ~0.1s time-scale measured for intracellular water flows in the cytoplasm of HeLa cells24.

To provide baseline behaviour for perturbation experiments, we measured the elastic and poroelastic properties of MDCK, HeLa, and HT1080 cells by fitting force-indentation and force-relaxation curves with Hertzian and poroelastic models, respectively. Measurement of average cell thickness suggested that for time-scales shorter than 0.5s, cells could be considered semi-infinite and forces relaxed according to a single exponential relationship with F(t)~e−Dpt/L2 (supplementary results, Fig. S10). In our experimental conditions (3.5-6nN force resulting in indentation depths less than 25% of cell height, Fig. S4C-D), force-relaxation with an average amplitude of 40% was observed with 80% of total relaxation occurring in ~0.5s (Fig. 1B, 1D). Analysis of the indentation curves yielded an elastic modulus of _E_=0.9±0.4 kPa for HeLa cells (N=189 curves on n=25 cells), _E_=0.4±0.2 kPa for HT1080 cells (N=161 curves on n=27 cells), and _E_=0.4±0.1 kPa for MDCK cells (n=20 cells). Poroelastic models fitted experimental force-relaxation curves well (on average _r2_=0.95, black line, Fig. 1B-II) and yielded a poroelastic diffusion constant of _Dp_=41±11 μm2.s−1 for HeLa cells, _Dp_=40±10 μm2.s−1 for HT1080 cells, and _Dp_=61±10 μm2.s−1 for MDCK cells.

Poroelasticity can predict changes in cell rheology associated with volume changes

We examined the ability of the simple scaling law Dp~ E ξ2/μ to qualitatively predict changes in Dp resulting from changes in pore size due to cell volume change, which should not affect cytoskeletal organisation or integrity but should alter cytoplasmic pore size. To change cell volume, we exposed HeLa and MDCK cells to hyperosmotic media to decrease cell volume and hypoosmotic media to increase cell volume and measured concomitant changes in Dp.

First, we ascertained that osmotically-induced volume changes persisted long enough for experimental measurements to be effected and that control cells retained a constant volume over this duration (Fig. 2A). To ensure a stable volume increase in hypoosmotic conditions, we treated cells with regulatory volume decrease inhibitors25 and measured a stable increase of 22±2% in cell volume after hypoosmotic treatment (Fig. 2A). Conversely, upon addition of 110 mM sucrose, cell volume decreased by 21±6% (Fig. 2A) and upon addition of PEG-400 (30% volumetric concentration), cell volume decreased drastically by 54±3% (Fig. 2A, Fig. S1E). Similar results were obtained for both cell types.

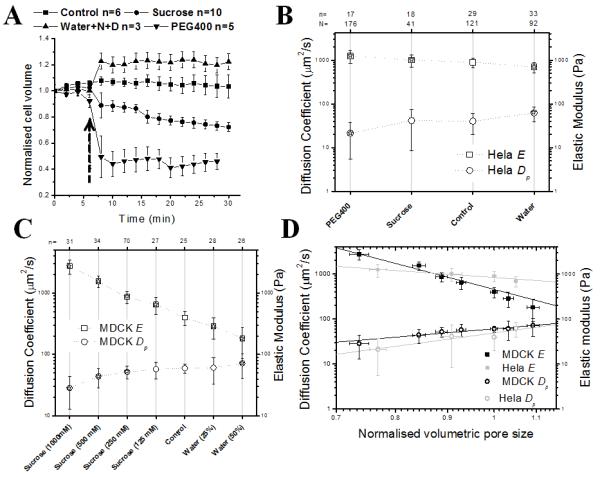

FIGURE 2. Poroelastic and elastic properties change in response to changes in cell volume.

In all graphs, error bars indicate the standard deviation and, in graphs B and C, asterisks indicate significant changes (p<0.01 compared to control). N indicates the total number of measurements and n indicates the number of cells. In hypoosmotic shock experiments, cells were incubated with NPPB and DCPIB (N+D on the graph), inhibitors of regulatory volume decrease. (A) Cell volume change over time in response to changes in extracellular osmolarity. The volume was normalized to the initial cell volume at _t_=0 s. The arrow indicates the time of addition of osmolytes. (B) Effect of osmotic treatments on the elasticity E (squares) and poroelastic diffusion constant Dp (circles) in HeLa cells. (C) Effect of osmotic treatments on the elasticity E (squares) and poroelastic diffusion constant Dp (circles) in MDCK cells. (D) Dp and E plotted as a function of the normalised volumetric pore size ψ~(V/V0)1/3 in log-log plots for MDCK cells (black squares and circles) and HeLa cells (grey squares and circles). Straight lines were fitted to the experimental data points weighted by the number of measurements to reveal the scaling of Dp and E with changes in volumetric pore size (grey lines for HeLa cells, E~ ψ−1.6 and Dp~ ψ2.9 and black lines for MDCK cells, _E~ ψ−5.9_and Dp~ ψ1.9).

Next, we asked if changes in cell volume resulted in changes in poroelastic diffusion constant in both cell types. Consistent with results by others26, our experiments revealed that cells relaxed less rapidly and became stiffer with decreasing fluid fraction. Increases in cell volume resulted in a significant increase in poroelastic diffusion constant Dp and a significant decrease in cellular elasticity E (Fig. 2B, C). In contrast, decrease in cell volume decreased the diffusion constant and increased elasticity (Fig. 2B, C). We verified that cytoskeletal organisation was not perturbed by changes in cell volume (Fig. S5 for actin), suggesting that change in pore size alone was responsible for the observed changes in Dp and E. Because the exact relationship between hydraulic pore size ξ and cell volume is unknown, we plotted Dp and E as a function of the change in the volumetric pore size ψ~(V/Vo)1/3. For both MDCK and HeLa cells, Dp scaled with ψ and the cellular elasticity E scaled inversely with ψ (Fig. 2D). In summary, increase in cell volume increased the poroelastic diffusion constant and decrease in cell volume decreased Dp, consistent with our simple scaling law.

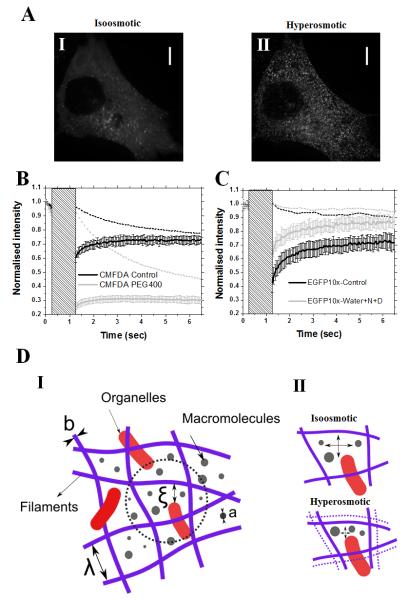

Changes in cell volume result in changes in cytoplasmic pore size

Having shown that changes in cell volume result in changes in poroelastic diffusion constant without affecting cytoskeletal structure, we tried to directly detect changes in pore size. To do this, we microinjected PEG-passivated quantum dots (~14nm hydrodynamic radius with the passivation layer27) into cells and examined their mobility. Under isoosmotic condition, quantum dots rapidly diffused throughout the cell; however, upon addition of PEG-400, they became immobile (supplementary movie, Fig. 3A, _n_=7 cells examined). Hence, cytoplasmic pore size decreased in response to cell volume decrease trapping quantum dots in the cytoplasmic solid fraction and immobilising them (Fig. 3D-II). This suggested that the isoosmotic pore radius ξ was larger than 14nm, consistent with our estimates from poroelasticity (supplementary results). Next, we verified that under hyperosmotic conditions cells retained a fluid fraction by monitoring recovery after photobleaching of a small fluorescein analog (CMFDA, hydrodynamic radius _Rh_~0.9nm 28). In isoosmotic conditions, CMFDA recovered rapidly after photobleaching (black line, Fig. 3B, supplementary table S1). In the presence of PEG-400, CMFDA fluorescence still recovered, indicating the presence of a fluid-phase, but recovery slowed three-fold, consistent with 29 (grey line, Fig. 3B). The measured decrease in translational diffusion suggested a reduction in the cytoplasmic pore size with dehydration. Indeed, translational diffusion is related to the solid fraction Φ via the relation DT/DT∞~exp(−Φ) with DT∞ the translational diffusion constant of the molecule in a dilute isotropic solution30. Assuming that the fluid is contained in N pores of equal radius ξ, the solid fraction is Φ~Vs/(Vs+Nξ3) with Vs the volume of the solid fraction, a constant. DT/DT∞ is therefore a monotonic increasing function of ξ. To examine the effect of volume increase on pore size, we examined the fluorescence recovery after photobleaching of a cytoplasmic GFP decamer (EGFP-10×, _Rh_~7.5nm). Increases in cell volume resulted in a significant ~2-fold increase in DT (p<0.01, Fig. 3C, supplementary table S1), suggesting that pore size did increase. Together, our experiments show that changes in cell volume modulate cytoplasmic pore size ξ consistent with estimates from AFM measurements (Fig. S6A-B).

FIGURE 3. Changes in cell volume change cytoplasmic pore size.

(A) Movement of PEG-passivated quantum dots microinjected into HeLa cells in isoosmotic conditions (I) and in hyperosmotic conditions (II). Both images are a projection of 120 frames totalling 18 s (supplementary movie). In isoosmotic conditions, quantum dots moved freely and the time-projection appeared blurry (I); whereas in hyperosmotic conditions, quantum dots were immobile and the time-projected image allowed individual quantum dots to be identified (II). Images A-I and II are single confocal sections. In (B) and (C), dashed lines indicate loss of fluorescence due to imaging in a region outside of the zone where fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was measured, solid lines indicate fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. These curves are the average of N measurements and error bars indicate the standard deviation for each time point. The greyed area indicates the duration of photobleaching. (B) FRAP of CMFDA (a fluorescein analog) in isoosmotic (black, N=19 measurements on n=7 cells) and hyperosmotic conditions (grey, N=20 measurements on n=5 cells). In both conditions, fluorescence recovered after photobleaching but the rate of recovery was decreased significantly in hyperosmotic conditions. (C) FRAP of EGFP-10× (a GFP decamer) in isoosmotic (black, N=17 measurements on n=6 cells) and hypoosmotic conditions (grey, N=23 measurements on n=7 cells). The rate of recovery was increased significantly in hypoosmotic conditions. (D) Schematic representation of the cytoplasm (I) The cytoskeleton and macromolecular crowding participate in setting the hydraulic pore size through which water can diffuse. The length-scales involved in setting cellular rheology are the average filament diameter b, the size a of particles in the cytosol, the hydraulic pore size ξ, and the entanglement length λ of the cytoskeleton. (II) Reduction in cell volume causes a decrease in entanglement length λ and an increase in crowding which combined lead to a decrease in hydraulic pore size ξ.

Poroelastic properties are influenced by the integrity of the cytoskeleton

Cytoskeletal organisation strongly influences cellular elasticity E31, and is also likely to affect the cytoplasmic pore size ξ (Fig. S7A-C). As both factors play antagonistic roles in setting Dp, we examined the effect of cytoskeletal perturbations.

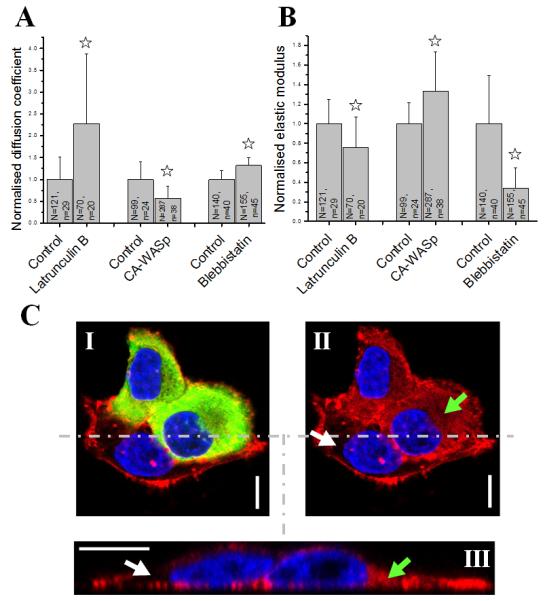

Treatment of cells with 750 nM latrunculin, a drug that depolymerises the actin cytoskeleton, resulted in a significant decrease in the cellular elastic modulus (Fig. 4B, consistent with 31), a ~two-fold increase in the poroelastic diffusion coefficient (Fig. 4A), and a significant increase in the lumped pore size (Fig. S6E). Depolymerisation of microtubules by treatment with 5 μM nocodazole had no significant effect (Fig. S6C-E). Stabilisation of microtubules with 350 nM taxol resulted in a small (−16%) but significant decrease in elasticity but did not alter Dp (Fig. S6C-E).

FIGURE 4. The F-actin cytoskeleton is the main biological determinant of cellular poroelastic properties.

(A) Effect of F-actin depolymerisation (Latrunculin treatment), F-actin overpolymerisation (overexpression of CA-WASp), and myosin inhibition (blebbistatin treatment) on the poroelastic diffusion constant Dp. (B) Effect of F-actin depolymerisation, F-actin overpolymerisation, and myosin inhibition on the cellular elasticity E. In A and B, asterisks indicate significant changes (p<0.01). N is the total number of measurements and n the number of cells examined. (C) Ectopic polymerization of F-actin due to CA-WASp. HeLa cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding GFP-CA-WASp (in green) and stained for F-actin with Rhodamine-Phalloidin (in red). Cells expressing high levels of CA-WASp (green, I) had more cytoplasmic F-actin (red, II, green arrow) than cells expressing no CA-WASp (II, white arrow). (III) zx profile of the cells shown in (I) and (II) taken along the dashed line. Cells expressing CA-WASp displayed more intense cytoplasmic F-actin staining (green arrow) than control cells (white arrow). Cortical actin fluorescence levels appeared unchanged. Nuclei are shown in blue. Images I and II are single confocal sections. Scale bars =10 μm.

In light of the dramatic effect of F-actin depolymerisation on Dp and ξ, we attempted to decrease the pore size by expressing a constitutively active mutant of WASp (WASp I294T, CA-WASp) that results in excessive polymerization of F-actin in the cytoplasm through ectopic activation of the arp2/3 complex, an F-actin nucleator (Fig. 4C, 32). Increased cytoplasmic F-actin due to CA-WASp resulted in a significant decrease in the poroelastic diffusion coefficient (−43%, p<0.01, Fig. 4A), a significant increase in cellular elasticity (+33%, p<0.01, Fig. 4B), and a significant decrease in the lumped pore size (−38%, p<0.01, supplementary Fig. S6E). Similar results were also obtained for HT1080 cells (−49% for Dp, +68% for E and −38% for lumped pore size, p<0.01). Then, we attempted to change cell rheology without affecting intracellular F-actin concentration by perturbing crosslinking or contractility. To perturb crosslinking, we overexpressed a deletion mutant of α-actinin (ΔABD-α-actinin) that lacks an actin-binding domain but can still dimerize with endogenous protein33, reasoning that this should either increase the F-actin gel entanglement length λ or reduce the average diameter of F-actin bundles b (Fig. 3D-I). Overexpression of ΔABD-α-actinin led to a significant decrease in E but no change in Dp or ξ (Fig. 4A-B, Fig. S6E). Perturbation of contractility with the myosin II ATPase inhibitor blebbistatin (100 μM) led to a 50% increase in Dp, a 70% decrease in E, and a significant increase in lumped pore size (Fig. 4A-B, Fig. S6E).

To determine if ectopic polymerisation of microtubules had similar effects to CA-WASp, we overexpressed γ-tubulin, a microtubule nucleator34, but found that this had no effect on cellular elasticity, poroelastic diffusion constant, or lumped pore size (Fig. S6C-E). Finally, expression of a dominant keratin mutant (Keratin 14 R125C,35) that causes aggregation of the cellular keratin intermediate filament network had no effect on E, Dp, or lumped pore size (Fig. S6C-E, S7C-D).

Discussion

Living cells exhibit poroelastic behaviours

We have shown that water redistribution plays a significant role in cellular responses to mechanical stresses at short time-scales and that the effect of osmotic and cytoskeletal perturbations on cellular rheology can be understood in the framework of poroelasticity through a simple scaling law Dp~ E ξ2/μ. Force-relaxation induced by fast localised indentation by AFM contained two regimes: at short time-scales, relaxation was poroelastic; while at longer time-scales, it exhibited a power law behaviour. We tested the dependence of Dp on the hydraulic pore size ξ by modulating cell volume and showed that Dp scaled proportionally to volume change, consistent with a poroelastic scaling law. Changes in cell volume did not affect cytoskeletal organisation but did modulate pore size. Experiments monitoring the mobility of microinjected quantum dots suggested that ξ was ~14nm consistent with estimates based on measured values for Dp and E (supplementary results). We also confirmed that cellular elasticity scaled inversely to volume change as shown experimentally26,36 and theoretically12 for F-actin gels and cells. However, the exact relationship between the poroelastic diffusion constant Dp and the hydraulic pore size ξ could not be tested experimentally because the relationship between volumetric change and change in ξ is unknown due to the complex nature of the solid phase of the cytoplasm (composed of the cytoskeletal gel, organelles, and macromolecules, Fig. 3D-I, 37). Taken together our results show that, for time-scales up to ~0.5s, the dynamics of cellular force-relaxation is consistent with a poroelastic behaviour for cells and that changes in cellular volume resulted in changes in Dp due to changes in ξ.

Role of intracellular water redistribution in cell rheology

Cell mechanical studies over the years have revealed a rich phenomenological landscape of rheological behaviours that are dependent upon probe geometry, loading protocol and loading frequency1-4, though the biological origin of many of these regimes remains to be fully explored. Spurred by recent reports implicating intracellular water flows in the creation of cellular protrusions8,9,16, we have examined the role of intracellular water redistribution in cellular rheology. Our experimental measurements indicated that intracellular fluid flows occurred for deformations applied with a rise time tr shorter than the poroelastic time tp~L2/Dp (~0.2s in our conditions), consistent with the time-scales of intracellular water flows observed in HeLa S3 cells24.

It may appear surprising that poroelastic effects have not been considered previously and we envisage several reasons for this. First, most studies to date have investigated cellular shear rheology using techniques such as magnetic twisting cytometry3,6,7 or bead tracking microrheology38, which only account for isochoric deformations and thus cannot be used to study dilatational rheology where volumetric deformations, such as those induced in our experiments, arise. Second, the time-scale of intracellular water flows is highly dependent on the volume of the induced deformation. Therefore, to observe poroelastic effects experimentally, large volumetric deformations must be induced and the cellular responses must be sampled at high rate (2000 Hz in our experiments). Thus, although clues to poroelastic behaviours exist in previous experiments examining whole-cell deformation with optical stretchers (which reported a short time-scale regime that could not be fit by power laws39) and previous AFM force-relaxation experiments (which reported the existence of a fast exponential decay occurring at short time scales40,41), they were not systematically examined. Third, previous work11 has shown that, in oscillatory experiments, for loading frequencies fp>>Eξ2/(μL2) (~5 Hz in our experimental conditions), the fluid will not move relative to the mesh and therefore that inertial and structural viscous effects from the mesh are sufficient to describe the system. Hence, intracellular water flows participate in cell rheology for loadings applied with rise times tr shorter than tp and repeated with frequencies lower than fp. Such a loading regime is particularly relevant for tissues of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems where the constituent cells are routinely exposed to large strains applied at high strain rates and repeated at low frequencies (e.g. 10% strain applied at ~50%.s−1 repeated at up to 4 Hz for arterial walls42, 70% strain applied at up to 900%.s−1 repeated at up to 4 Hz in the myocardial wall43, and 20% strain applied at >20%.s−1 repeated at ~1 Hz for lung alveola44). Further intuition for the significance of poroelastic effects during physiological cellular shape changes can be gained by computing a poroelastic Péclet number (see supplementary discussion).

Over the time-scales of our experiments (~5s), other factors such as turnover of cytoskeletal fibres and cytoskeletal network rearrangements due to crosslinker exchange or myosin contractility might also in principle influence cell rheology. In our cells, F-actin, the main cytoskeletal determinant of cellular rheology (Fig. 4 and 45,46), turned over with a half-time of ~11s (Fig. S7C), crosslinkers turned over in ~20s47, and myosin inhibition led to faster force-relaxation. Hence, active biological remodelling cannot account for the dissipative effects observed in our force-relaxation experiments. Taken together, the time-scale of force-relaxation, the functional form of force-relaxation, and the qualitative agreement between the theoretical scaling of Dp with experimental changes to E and ξ support our hypothesis that water redistribution is the principal source of dissipation at short time-scales in our experiments. .

Hydraulic pore size is distinct from cytoskeletal entanglement length

Although the cytoskeleton plays a fundamental role in modulating cellular elasticity and rheology, our studies show that microtubules and keratin intermediate filaments do not play a significant role in setting cellular rheological properties (Fig. S6C-E). In contrast, both the poroelastic diffusion constant and elasticity strongly depended on actomyosin (Fig. 4). Our experiments qualitatively illustrated the relative importance of ξ and E in determining Dp. Depolymerising the F-actin cytoskeleton decreased E and increased pore size resulting in an overall increase in Dp. Conversely, when actin was ectopically polymerised in the cytoplasm by arp2/3 activation by CA-WASp (Fig. 4), E increased and the pore size decreased resulting in a decrease in Dp. For both perturbations, changes in pore size ξ dominated over changes in cellular elasticity in setting Dp. For dense crosslinked F-actin gels, theoretical relationships between the entanglement length λ and the elasticity E suggest that E~κ2/(kBTλ5) with κ the bending rigidity of the average F-actin bundle of diameter b, kB the Boltzmann constant, and T the temperature12 (Fig. 3D-I). If the hydraulic pore size ξ and the cytoskeletal entanglement length λ were identical, Dp would scale as Dp~κ2/(μkBTλ3) implying that changes in elastic modulus would dominate over changes in pore size, in direct contradiction with our results. Hence, ξ and λ are different and ξ may be influenced both by the cytoskeleton and macromolecular crowding37 (Fig. 3D-I).

To decouple changes in elasticity from gross changes in intracellular F-actin concentration, we decreased E by reducing F-actin crosslinking through overexpression of a mutant α-actinin33 that can either increase the entanglement length λ or decrease the bending rigidity κ of F-actin bundles by diminishing their average diameter b (Fig. 3D-I). Overexpression of mutant α-actinin led to a decrease in E but no detectable change in Dp or ξ confirming that pore size dominates over elasticity in determining cell rheology. Finally, myosin inhibition led to an increase in Dp, a decrease in E, and an increase in ξ, indicating that myosin contractility participates in setting rheology through application of pre-stress to the cellular F-actin mesh13, something that results directly or indirectly in a reduction in pore size13,48. Taken together, these results show that F-actin plays a fundamental role in modulating cellular rheology but further work will be necessary to understand the relationship between hydraulic pore size ξ, cytoskeletal entanglement length λ, crosslinking, and contractility in living cells.

Cellular rheology and hydraulics

Though the poroelastic framework can mechanistically describe cell rheology at short-time scales and predict changes of Dp in response to changes in microstructural and constitutive parameters, the minimal formulation provided here does not yet provide a complete framework for explaining the rich phenomenology of rheological behaviours observed over a wide ranges of time scales. However, building on the poroelastic framework’s ability to link cell rheology to microstructural and constitutive parameters, it may be possible to extend its domain of applicability by including additional molecular and structural detail such as a more complex solid meshwork with the characteristics of a crosslinked F-actin gel12 with continuous turnover and protein unfolding49,50, or considering the effects of molecular crowding on the movement of interstitial fluid.

Further intuition for the complexity and variety of length scales involved in setting cellular rheology (Fig. 3D-I) can be gained by recognising that the effective viscosity μ felt by a particle diffusing in the cytosol will depend on its size (Fig. 3, Fig. S5 and 51,52). Within the cellular fluid fraction, there exists a wide distribution of particle sizes with a lower limit on the radius set by the radius of water molecules. Whereas measuring the poroelastic diffusion constant Dp remains challenging, the diffusivity Dm of any given particle can be measured accurately in cells. For a molecule of radius a, the Stokes-Einstein relationship gives Dm=kBT/(6πμa) or μ(a)=kBT/(6πDma). Any interaction between the molecule and its environment (e.g. reaction with other molecules, crowding and hydrodynamic interactions53, size-exclusion52) will result in a deviation of the experimentally determined Dm from this relationship. Using the previous relationship for elasticity of gels and recalling that the bending rigidity of filaments scales as κ~Epolymerb4 (with b the average diameter of a filament - or bundle of filaments - and Epolymer the elasticity of the polymeric material54), we obtain the relationship

Dp∼(ξ2aEpolymer2b8(kBT)2λ5)Dm

in which four different length-scales contribute to setting cellular rheology. We see that the average filament bundle diameter b, the size of the largest particles in the cytosol a (and indeed the particle size distribution in the cytosol), the entanglement length λ, and the hydraulic pore size ξ together conspire to determine the geometric, transport, and rheological complexity of the cell (Fig. 3D-I). Since all these parameters can be dynamically controlled by the cell, it is perhaps not surprising that a rich range of rheologies has been experimentally observed in cells1-7,9,10.

METHODS

Cell culture

Details on cell culture, drug treatments, and genetic treatments are provided in the supplementary information.

Atomic force microscopy measurements

During AFM experiments, measurements were acquired in several locations in the cytoplasm avoiding the nucleus. To maximize the amplitude of stress relaxation, the cantilever tip was brought into contact with the cells using a fast approach speed (Vapproach ~ 10-30 μm.s−1) until reaching a target force set to achieve an indentation depth δ~1μm (Fig. 1A-I, 1A-II, 1B). Force was applied onto the cells in less than 35-100 ms, short compared to the experimentally observed relaxation time. Upon reaching the target force FM the piezoelectric ceramic length was kept at a constant length and the force-relaxation curves were acquired at constant Z_M_ sampling at 2000 Hz (Fig. 1A-III, A-IV). After 10s, the AFM tip was retracted.

Measurement of the poroelastic diffusion coefficient

A brief description of the governing equations of linear isotropic poroelasticity and the relationship between the poroelastic diffusion constant Dp, the elastic modulus E, and hydraulic permeability k are given in supplementary information. We analysed our experiments as force-relaxation in response to a step displacement of the cell surface. No closed form analytical solution for indentation of a poroelastic infinite half space by a spherical indentor exists. However, an approximate solution obtained by Finite-Element (FE) simulations gives22:

| F(t)−FfFi−Ff=0.491e−0.908τ+0.509e−1.679τ | (1) |

|---|

where τ=Dpt/Rδ is the characteristic poroelastic time required for force to relax from Fi to Ff. Cells have a limited thickness h and therefore the infinite half-plane approximation is only valid at time-scales shorter than the time needed for fluid diffusion through the cell thickness: thp ~h2/Dp. In our experiments on HeLa cells, we measured _h_~5 μm and _Dp_~40 μm2.s−1 setting a time-scale _thp_~0.6s. We confirmed numerically that for times shorter than ~0.5 s, approximating the cell to a half-plane gave errors of less than 20% (supplementary results, Fig. S10). For short time-scales, both terms in equation (1) are comparable and hence as a first approximation, the relaxation scales as ~e−τ. Equation (1) was utilized to fit our experimental relaxation data, with Dp as single fitting parameter and we fitted only the first 0.5 s of relaxation curves to consider only the maximal amplitude of poroelastic relaxation and minimise errors arising from finite cell thickness.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Movie

Acknowledgements

EM is in receipt of a Dorothy Hodgkin Postgraduate Award (DHPA) from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. LM thanks the MacArthur Foundation for support. GC is in receipt of a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. GC, DM and AT are funded by Wellcome Trust grant (WT092825). MF was supported by a Human Frontier Science Program young investigator grant to GC. The authors wish to acknowledge the UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre for generous funding of microscopy equipment. EM and GC thank Dr. R. Thorogate and Dr. C. Leung for technical help with the AFM setup and Dr. Z. Wei for helpful discussions. We also gratefully acknowledge support of Prof. N. Ladommatos and Dr. W. Suen from Department of Mechanical Engineering at UCL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffman BD, Crocker JC. Cell mechanics: dissecting the physical responses of cells to force. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2009;11:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher DA, Geissler PL. Active biological materials. Annual review of physical chemistry. 2009;60:469–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.040808.090304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trepat X, Lenormand G, Fredberg JJ. Universality in cell mechanics. Soft Matter. 2008;4:1750–1759. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollmannsberger P, Fabry B. Linear and nonlinear rheology of living cells. Annual Review of Materials Research. 2011;41:75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bausch AR, Möller W, Sackmann E. Measurement of local viscoelasticity and forces in living cells by magnetic tweezers. Biophysical journal. 1999;76:573–579. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77225-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabry B, et al. Scaling the microrheology of living cells. Physical review letters. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng L, et al. Fast and slow dynamics of the cytoskeleton. Nature materials. 2006;5:636–640. doi: 10.1038/nmat1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charras GT, Yarrow JC, Horton MA, Mahadevan L, Mitchison TJ. Non-equilibration of hydrostatic pressure in blebbing cells. Nature. 2005;435:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature03550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keren K, Yam PT, Kinkhabwala A, Mogilner A, Theriot JA. Intracellular fluid flow in rapidly moving cells. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:1219–1224. doi: 10.1038/ncb1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bausch AR, Kroy K. A bottom-up approach to cell mechanics. Nature Physics. 2006;2:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gittes F, Schnurr B, Olmsted PD, MacKintosh FC, Schmidt CF. Microscopic viscoelasticity: shear moduli of soft materials determined from thermal fluctuations. Physical review letters. 1997;79:3286–3289. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardel ML, et al. Elastic behavior of cross-linked and bundled actin networks. Science. 2004;304:1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1095087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuno D, Tardin C, Schmidt CF, MacKintosh FC. Nonequilibrium mechanics of active cytoskeletal networks. Science. 2007;315:370. doi: 10.1126/science.1134404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbluth MJ, Crow A, Shaevitz JW, Fletcher DA. Slow stress propagation in adherent cells. Biophysical journal. 2008;95:6052–6059. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charras GT, Mitchison TJ, Mahadevan L. Animal cell hydraulics. Journal of Cell Science. 2009;122:3233. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zicha D, et al. Rapid actin transport during cell protrusion. Science. 2003;300:142–145. doi: 10.1126/science.1082026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biot MA. General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. Journal of applied physics. 1941;12:155. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Gennes PG. Dynamics of entangled polymer solutions (I&II) Macromolecules. 1976;9:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchison TJ, Charras GT, Mahadevan L. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; pp. 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dembo M, Harlow F. Cell motion, contractile networks, and the physics of interpenetrating reactive flow. Biophysical journal. 1986;50:109–121. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, Zhao X, Vlassak JJ, Suo Z. Using indentation to characterize the poroelasticity of gels. Applied Physics Letters. 2010;96:121904. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalcioglu ZI, Mahmoodian R, Hu Y, Suo Z, Van Vliet KJ. From macro-to microscale poroelastic characterization of polymeric hydrogels via indentation. Soft Matter. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibata K, Takimoto S, Morisaku T, Miyawaki A, Yasui M. Analysis of Aquaporin-Mediated Diffusional Water Permeability by Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy. Biophysical journal. 2011;101:2277–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:193. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou EH, et al. Universal behavior of the osmotically compressed cell and its analogy to the colloidal glass transition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:10632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901462106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derfus AM, Chan WCW, Bhatia SN. Intracellular delivery of quantum dots for live cell labeling and organelle tracking. Advanced Materials. 2004;16:961–966. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swaminathan R, Bicknese S, Periasamy N, Verkman AS. Cytoplasmic viscosity near the cell plasma membrane. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao HP, Abney JR, Verkman AS. Determinants of the translational mobility of a small solute in cell cytoplasm. The Journal of cell biology. 1993;120:175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips RJ. A hydrodynamic model for hindered diffusion of proteins and micelles in hydrogels. Biophysical Journal. 2000;79:3350. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76566-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotsch C, Radmacher M. Drug-induced changes of cytoskeletal structure and mechanics in fibroblasts: an atomic force microscopy study. Biophysical journal. 2000;78:520–535. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76614-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moulding DA, et al. Unregulated actin polymerization by WASp causes defects of mitosis and cytokinesis in X-linked neutropenia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Low SH, Mukhina S, Srinivas V, Ng CZ, Murata-Hori M. Domain analysis of α-actinin reveals new aspects of its association with F-actin during cytokinesis. Experimental cell research. 2010;316:1925–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu HB, Joshi HC. Gamma-tubulin can both nucleate microtubule assembly and self-assemble into novel tubular structures in mammalian cells. The Journal of cell biology. 1995:1137–1147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werner NS, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex-type mutations alter the dynamics of the keratin cytoskeleton and reveal a contribution of actin to the transport of keratin subunits. Molecular biology of the cell. 2004;15:990. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spagnoli C, Beyder A, Besch S, Sachs F. Atomic force microscopy analysis of cell volume regulation. Physical Review E. 2008;78:31916. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.031916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albrecht-Buehler G, Bushnell A. Reversible compression of cytoplasm. Experimental cell research. 1982;140:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(82)90168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman BD, Massiera G, Van Citters KM, Crocker JC. The consensus mechanics of cultured mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:10259–10264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wottawah F, et al. Optical rheology of biological cells. Physical review letters. 2005;94:98103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.098103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darling EM, Zauscher S, Guilak F. Viscoelastic properties of zonal articular chondrocytes measured by atomic force microscopy. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2006;14:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreno-Flores S, Benitez R, Vivanco MM, Toca-Herrera JL. Stress relaxation and creep on living cells with the atomic force microscope: a means to calculate elastic moduli and viscosities of cell components. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:445101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/44/445101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avril S, Schneider F, Boissier C, Li ZY. In vivo velocity vector imaging and time-resolved strain rate measurements in the wall of blood vessels using MRI. J Biomech. 2011;44:979–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.12.010. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li P, et al. Assessment of strain and strain rate in embryonic chick heart in vivo using tissue Doppler optical coherence tomography. Physics in medicine and biology. 2011;56:7081. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/22/006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perlman CE, Bhattacharya J. Alveolar expansion imaged by optical sectioning microscopy. Journal of applied physiology. 2007;103:1037–1044. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00160.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Citters KM, Hoffman BD, Massiera G, Crocker JC. The role of F-actin and myosin in epithelial cell rheology. Biophysical journal. 2006;91:3946–3956. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trepat X, et al. Universal physical responses to stretch in the living cell. Nature. 2007;447:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukhina S, Wang Y, Murata-Hori M. [alpha]-Actinin Is Required for Tightly Regulated Remodeling of the Actin Cortical Network during Cytokinesis. Developmental cell. 2007;13:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart MP, et al. Hydrostatic pressure and the actomyosin cortex drive mitotic cell rounding. Nature. 2011;469:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature09642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DiDonna B, Levine AJ. Unfolding cross-linkers as rheology regulators in F-actin networks. Physical Review E. 2007;75:041909. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.041909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoffman BD, Massiera G, Crocker JC. Fragility and mechanosensing in a thermalized cytoskeleton model with forced protein unfolding. Physical Review E. 2007;76:051906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.051906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luby-Phelps K, Castle PE, Taylor DL, Lanni F. Hindered diffusion of inert tracer particles in the cytoplasm of mouse 3T3 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1987;84:4910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dix JA, Verkman AS. Crowding effects on diffusion in solutions and cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:247–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ando T, Skolnick J. Crowding and hydrodynamic interactions likely dominate in vivo macromolecular motion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:18457–18462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011354107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gittes F, Mickey B, Nettleton J, Howard J. Flexural rigidity of microtubules and actin filaments measured from thermal fluctuations in shape. The Journal of cell biology. 1993;120:923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Movie