Transition to Adult Care for Youth with Type 1 Diabetes (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Jul 3.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Diab Rep. 2012 Oct;12(5):533–541. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0311-6

Abstract

Emerging adults with type 1 diabetes are at risk for poor glycemic control, gaps in medical care, and adverse health outcomes. With the increasing incidence in type 1 diabetes in the pediatric population, there will be an increase in the numbers of teens and young adults transferring their care from pediatric providers to adult diabetes services in the future. In recent years, the topic of transitioning pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes to adult diabetes care has been discussed at length in the literature and there have been many observational studies. However, there are few interventional studies and, to date, no randomized clinical trials. This paper discusses the rationale for studying this important area. We review both observational and interventional literature over the past several years, with a focus on new research. In addition, important areas for future research are outlined.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Transition, Young adults, Pediatrics, Gaps in care, Complications, Adult care, Glycemic control, HbA1c, Health care delivery

Introduction

The incidence of type 1 diabetes in the pediatric population has increased substantially in the last 50 years and is expected to increase further in the next 15–20 years [1–12]. Recent data from the SEARCH study have confirmed a 23 % increase in the prevalence of type 1 diabetes in the United States between 2001 and 2009 [13]. Thus, there have been and will continue to be increasing numbers of older teens and young adults preparing to transfer their care from pediatric to adult diabetes providers. While the overwhelming majority of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes receive their diabetes care from specialists such as endocrinologists [14], the majority of adults with diabetes, whether diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, receive their care from primary care providers. There are many particular challenges that face the emerging young adult with type 1 diabetes. This article will review the unique issues related to older teens and young adults with type 1 diabetes; provide a review of the extant literature on observational, longitudinal, and intervention studies; and offer an approach for an ongoing research agenda to fill the gaps and improve the care and outcomes for emerging young adults with type 1 diabetes.

Unique Challenges Faced by Emerging Young Adults and Impact on Glycemic Control

“Emerging Adulthood” is a unique developmental stage that spans the ages of 18–30 years [15, 16]. According to contemporary thinking, the period of emerging adulthood follows adolescence and precedes true adulthood, which then begins in the late 20s or early 30s. Compared with previous times, modern cultural trends have set the stage for young persons to delay assuming responsibilities and typical adult roles like marriage, parenting, and work. The period of emerging adulthood is subdivided into an earlier stage, ages 18–24, encompassing the years immediately after high school, and a later stage, ages 25–30, when the maturing young adult begins to take on more traditional adult roles [15, 16]. With respect to managing a chronic, demanding disease like type 1 diabetes, this period of emerging adulthood is fraught with upheaval as the young person is often separating geographically, emotionally, and economically away from the family home while also transitioning between pediatric and adult diabetes care providers [17••].

During this stage, the young person also faces many competing social, emotional, educational, occupational, and/or financial priorities that often trump the demands of diabetes self-care [18, 19, 20•]. As a result, older teens and young adults with type 1 diabetes are at particularly high risk for non-adherence, poor glycemic control, and loss-to-follow-up care [21–25]. This stage can be especially challenging if the young person is also struggling with issues related to depression, anxiety, or disordered eating behaviors, among other mental health problems which require consistent and effective follow-up care.

As an additional impediment to optimal diabetes management, this period of emerging adulthood represents the time when patients usually transfer between pediatric and adult diabetes care providers. This often creates additional challenges for the young adult who may be ill-prepared to assume all the necessary self-care responsibilities that are expected, in particular, by adult providers. As a result, the emerging adult, while struggling with the daily demands of diabetes self-management, may feel unsupported and vulnerable such that she or he finds it easier to avoid follow-up care than be faced with the need to attend more to self-management and be confronted with a series of medical evaluations aimed at screening for diabetes-related complications. Naturally, the unprepared young adult will choose to focus on pursuing more typical age-appropriate educational, occupational, and social activities. Thus, it is not surprising that adherence to self-care behaviors, glycemic control, screening for complications, and medical follow-up care are often not a priority for the emerging young adult.

Pediatric Diabetes: Preparation for Self-care, Transitions, and Transfer to Adult Care Teams

It is estimated that ~18 % of youth in the United States have some sort of special health care need and the overwhelming majority of these youth grow up and enter adulthood [26]. Thus, it is not surprising that there has been burgeoning interest regarding effective transitions from pediatric to adult medical care teams in general and for young patients with diabetes in particular, especially since type 1 diabetes is one of the most common, serious chronic diseases of childhood, second only to asthma in frequency. There have been multiple position statements written and endorsed by leading organizations that provide guidance on approaches to transition [17••, 27–29]. In 1 approach, “Got Transition,” 6 core practice elements comprise the health care transition program (www.gottransition.org/), with application of each element to the pediatric and adult care teams. The core elements include a transition policy for pediatric patients and a young adult privacy and consent policy; youth and young adult patient registries; transition preparation; transition planning; transition and transfer of care; and transition completion. Other organizations, such as the National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP) and the Endocrine Society, have generated materials based upon expert consensus to support the process (www.YourDiabetes Info.org/transitions) (www.endo-society.org/clinicalpractice/transition_of_care.cfm).

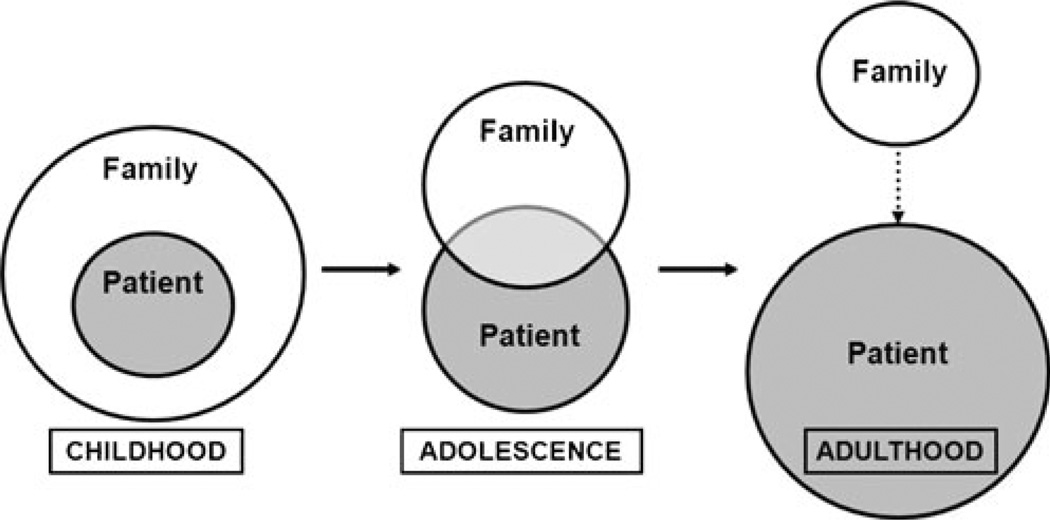

Type 1 diabetes requires unending attention to management tasks related to glucose monitoring, carbohydrate intake, insulin administration, exercise, and sick day management, which are influenced by multiple factors such as stress, growth, pubertal development, and other factors. In childhood, these tasks are managed solely by parents, guardians, school staff, and other adults. As the child grows and matures, there is a gradual transfer of diabetes responsibilities from parents to youth, while parents remain involved and supportive in a supervisory role (Fig. 1). As the youth ages and requires greater independence, she/he accepts more responsibilities and gradually takes over self-care tasks. There is no exact age at which these transitions in management occur as care must be individualized. Nonetheless, it is recommended that these processes begin in the early teen years, starting at ages 12 to 13 years, with education in self-care behaviors and implementation of a transition plan. Transition is a process that takes place while the youth is in the care of the pediatric diabetes team. The moment of transfer from pediatric to adult teams requires an orchestrated hand-off between providers. The following sections outline recent literature that highlights the process of transition and potential challenges that arise after an unsuccessful transfer in care. A review of observational studies precedes a discussion of interventional studies.

Fig. 1.

From family-managed diabetes care to shared care to self-care. In childhood, parents are responsible for all of diabetes management. As youth get older, they begin to take on more responsibility for their care while the family continues to provide support and supervision. Eventually, older teens and young adults assume full responsibility for diabetes self-care behaviors, although family support remains helpful for patients of all ages throughout the lifespan

Observational Studies

Emerging adults with type 1 diabetes are at risk for gaps in medical care and adverse health outcomes, including suboptimal glycemic control, early onset of chronic diabetes complications, and premature mortality [22, 23, 30–34]. To ensure optimal outcomes, patients in this population require ongoing support during the transition to adult diabetes care. However, empiric evidence on post-transition outcomes is limited, particularly in the United States, and virtually all published data are from cross-sectional or retrospective observational studies.

Gaps Between Pediatric and Adult Diabetes Care

Early studies in Canada, where health care transition is mandated at 18 years of age, established the presence of important difficulties in the transition process. Frank [35] interviewed 41 patients (mean age 21.5 years) discharged from pediatric endocrinology clinic at age 18 years in Toronto and found that 24 % were still not being followed medically. Pacaud and colleagues surveyed 135 post-transition young adults in Quebec who had received care at a single pediatric center; 28 % reported delays greater than 6 months in establishing adult diabetes care [36]. Several years later, the same survey was administered to a different sample of 81 post-transition young adults in Alberta; 31 % of subjects reported gaps greater than 6 months between pediatric and adult care [37].

Along similar lines, in our recent U.S. survey of 258 post-transition young adults in Boston, 34 % reported a gap greater than 6 months between pediatric and adult care. Respondents who felt mostly or completely prepared for transition by their pediatric diabetes providers were significantly less likely to report gaps in care greater than 6 months (adjusted odds ratio 0.47, 95 % CI 0.25, 0.88), as were those who had 3 or more pediatric diabetes visits in the year prior to transition (adjusted odds ratio 0.35, 95 % CI 0.19, 0.63) [38•].

Post-Transition Health Care Utilization

Patients with delays between pediatric and adult diabetes care also may be at risk for further loss-to-follow-up in adult care. In addition, previous research has shown an increased incidence of acute and chronic diabetes complications in adolescents and young adults with infrequent clinic follow-up [32, 39, 40].

In the United Kingdom, Kipps and colleagues compared clinic attendance patterns in 229 older teen and young adult patients with type 1 diabetes from 4 districts employing different transition strategies. Overall, 94 % of patients had a high rate of clinic attendance (at least every 6 months) in the 2 years before transition, but this rate declined significantly post-transition to 57 %, (P<0.0005). Higher post-transition follow-up rates (63 %–71 % vs 29 %–57 %) were noted in districts where patients were able to meet their adult diabetes providers prior to transition, a finding that was supported by observations from patient interviews [41].

In Germany, Busse and colleagues conducted telephone surveys with 101 young adults who transitioned from a single pediatric diabetes center. Adult clinic follow-up rates were generally high, but nonetheless, there was a significant decrease in clinic attendance rate after transition (8.5±2.3 visits per year pre-transition vs 6.7±3.2 per year post-transition) [42]. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study analyzing data from 104 patients who transitioned from a single pediatric center in Sweden, Sparud-Lundin and colleagues found that the mean number of diabetes clinic visits declined between pediatric care (3.6±1 visits per year) and adult care (2.7±1 visits per year). During the retrospective follow-up study period, in which patients were 18 to 24 years of age, less than 10 % of patients had hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in the recommended range and ‘background’ retinopathy as reported in the paper increased from 5 % to 29 % [43].

Diabetes-related inpatient hospitalizations are an important aspect of post-transition health care utilization. Nakhla and colleagues analyzed a large retrospective cohort of 1507 transitioning patients with type 1 diabetes in the Ontario Diabetes Database and showed that diabetes-related hospitalizations increased from 7.6 to 9.5 per 100 patient-years in the 2 years after transition to adult care (_P_=0.03). After controlling for factors including gender, income, and pre-transition diabetes-related hospitalizations, the study further found that patients who continued with the same diabetes physician after transition (even if the allied health care team changed) were 77 % less likely to have post-transition diabetes-related hospitalizations. However, the rates of eye examination in the 2-year periods before and after transition were not significantly different (72 % vs 70 %, _P_=0.06) [44•].

Glycemic Control

Age-based HbA1c target ranges recommended by the American Diabetes Association are less than 7.5 % at 13 to 18 years of age and less than 7 % at ≥19 years of age [45]. For most adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes, achieving glycemic control in these target ranges remains an elusive goal. The cross-sectional, multicenter SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study showed that only 32 % of patients with type 1 diabetes aged 13–18 years (_n_=1499) and 18 % of patients aged ≥19 (_n_=298) years met these recommended HbA1c targets [14]. However, data are limited to describe patterns of glycemic control across the health care transition or the impact of specific transition factors upon HbA1c.

Several cross-sectional and observational studies have examined HbA1c values around the health care transition and found no significant differences, although conclusions are generally limited by lack of prospective design. In the German study by Busse and colleagues, pre- and post-transition measured HbA1c data were available for only 44 of 101 subjects, with no significant differences (pre-transition HbA1c 8.5±1.5 % vs 8.3±1.6 %, _P_=0.44) [42]. Another German study by Neu and colleagues attempted to follow patients with annual surveys after transition, but enrollment progressively declined each year due to lack of participant response. Measured glycemic control data were presented for 99 patients at the start of the study but for only 34 patients after 1 year and 12 patients at 5 years. There was a trend towards mild improvement in HbA1c over time (7.7 ±1.2 % at baseline and 7.1±1.6 % at 5 years), but the small sample size limits interpretation [46]. In Sweden, over a 7-year retrospective observational period in the study by Sparud-Lundin and colleagues, bivariate analyses showed a significant trend towards post-transition HbA1c decreases in women, but not men [43].

In addition to the analysis of gaps between pediatric and adult diabetes care described above, our recent survey of 258 post-transition young adults in Boston also examined relationships between health care transition preparation and glycemic control. Subjects were 26.7±2.4 years old with mean HbA1c 8.1 %±1.3 %. Overall, 63 % of subjects felt mostly or completely prepared for transition by their pediatric team, although none participated in formal transition programs. In multivariate linear regression, average current HbA1c was 0.49 % higher for each percent increase in pediatric pre-transition HbA1c (β 0.49, P<0.0001). Higher education (β −0.55, _P_=0.01) was inversely correlated with post-transition HbA1c, but there was no independent association of transition preparation with glycemic control (β −0.17, _P_=0.28) [38•].

The above studies highlight close associations between pre- and post-transition HbA1c and underscore the importance of preventing deterioration in glycemic control during adolescence, since adolescent control generally seems to predict young adult glycemic control. However, patients in these studies were not part of transition program interventions, which are likely required to improve young adult HbA1c outcomes.

Perceptions of the Transition Process

In most published studies exploring young adults’ perceptions of transition, some dissatisfaction with the transition process is a common theme. For example, in the UK study by Kipps and colleagues comparing outcomes in 4 districts in the UK, 20 % of the 106 interviewed subjects reported feeling “not satisfied” with the transition. The proportion of dissatisfied subjects was significantly increased (47 %) in patients who did not attend a specialized young adult diabetes clinic [41]. In Germany, 58 % of the 101 subjects interviewed by Busse and colleagues reported negative transition experiences. These negative experiences included lack of transition preparation, problems finding suitable adult diabetes providers, feeling lost or alone in the adult care system, and feeling surprised by the differences from pediatric to adult care [42].

In our survey of 258 post-transition patients in a single adult diabetes clinic who had received pediatric diabetes care at 95 different centers across the United States, only 36 % were mostly satisfied and 26 % completely satisfied with their transition experience. Transition satisfaction (mostly/completely satisfied) and report of transition preparation (mostly/completely prepared) were very highly associated (P<0.0001) [38•].

In previously unpublished data from our survey, we examined self-reported perceived differences between pediatric and adult diabetes clinic settings. Overall, 60 %–80 % of respondents selected “agree” or “strongly agree” for their experiences with various aspects of pediatric and adult diabetes care, such as time spent with patient, perceived listening and caring, goal setting, and clinic access for prescriptions or urgent questions. However, we found interesting differences in the agree/strongly agree response rank order between pediatric and adult care attributes. For example, report of provider goal setting was ranked at the top for adult care, but was the least endorsed for pediatric care. In contrast, easy access to the clinic for prescription refills or urgent questions was ranked highly for pediatric care but at the bottom of the list for adult care.

Delving more deeply into these issues, qualitative work has further elucidated key themes about the change from pediatric to adult clinical settings. Dovey-Pearce and colleagues utilized semi-structured interview and focus group methods to organize young adults’ suggestions for developmentally appropriate diabetes care. Major themes included the need for staff consistency and civility and navigable clinic structures that do not overwhelm transitioning patients, as well as support for emotional and social as well as medical demands [47]. Visentin and colleagues conducted semi-structured interviews with both young adult patients and pediatric and adult providers. Data from this study revealed major differences between pediatric and adult diabetes care models, including a less friendly and more formal environment, less parent involvement, increased patient responsibility, and greater focus on diabetes complications in adult care systems [48].

Interventional Studies

To date, there have been no randomized clinical trials examining the efficacy of structured transition programs. However, both structured and unstructured transition programs have been reported and evaluated in the literature. Structured transition programs, consisting of procedures and guidelines to help patients transfer to adult care, have been shown to result in better outcomes than unstructured transfers, resulting in less loss-to-follow-up care, shorter gaps in care, lower HbA1c at first adult visit, fewer admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), and fewer long-term complications.

Dedicated Young Adult Clinics

One of the first studies on transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care was conducted in Indiana by Orr and colleagues [49]. They followed pediatric patients before and after the transfer to a young adult clinic (age ~17 years). The major finding from this study is that HbA1c was unchanged a year after transfer (_P_=0.15), suggesting that transitioning to a young adult clinic did not have a negative impact on glycemic control.

In Nebraska, Lane and colleagues [50] retrospectively evaluated participation in and outcomes from a young adult clinic compared with a general endocrinology clinic over a period from 1999 to 2005. Providers in the young adult clinic saw patients at least every 3 months, and included an endocrinologist, 2 nurse educators, and 2 dieticians. Follow-up contact was encouraged and education was provided, both in an individual setting as well as a group class on pattern management. The general endocrinology clinic consisted of a larger number of providers who saw patients for appointments every 3–6 months. Mean age was younger by 2 years in the young adult clinic (P<0.001) and no patients were treated for hypertension in the young adult clinic (_P_=0.03). The no-show rates for both clinics were similar (_P_=0.20). HbA1c did not differ between groups and HbA1c declined over time in both groups (P<0.002).

Holmes-Walker and colleagues [39] developed and implemented a program in Australia to help young adults, ages 15–25 years, maintain attendance at a young adult clinic and reported data over a 5 year period. The program consisted of a transition coordinator who made contact with participants prior to each appointment, helped rebook missed appointments, and booked appointments every 3 months. The program also consisted of after-hours phone support, which was only available to people in the program. Participation in the program was associated with a decrease in HbA1c (P<0.001), a reduction in hospital admissions for DKA (P<0.05), as well as a reduction in length of hospital stay for those participants who had more than 1 hospital admission over a 12 month period (_P_=0.02).

In 2008, Logan and colleagues in the UK [51] designed and implemented an intervention consisting of a year-long transition clinic, comprised of both pediatric and adult medical providers, which feeds into a young adult clinic which is held in the evening. Pediatric patients have their last 3 visits in the transition clinic with both pediatric and adult providers prior to the transition to the young adult clinic. The clinic group holds annual focus groups with patients in the transition age group to identify features of a young adult clinic that would be ideal for patients. One of the unique aspects of this young adult clinic is that patients have 3 appointments spread over a year and patients can choose which member of the team they would like to meet with for 2 of the 3 appointments (diabetes doctor, diabetes nurse, dietician, clinical psychologist). They are only required to have a medical assessment annually. Over 3 years, the young adult clinic achieved an 84 % attendance rate, as well as a drop in HbA1c from first to third visit (9.7 % to 9.0 %, _P_=0.008). In addition, percentage of patients achieving an HbA1c <7.5 increased significantly (_P_=0.01).

Care Coordination and Transition Planning

Van Walleghem and colleagues [52] have designed and implemented an intervention in Canada using care coordination, called The Maestro Project, to help young adults ages 18–25 years maintain connection with their providers as they transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care. The ‘Maestro,’ or systems navigator, has consistent contact with participants to provide support and help them access medical care. The program also has a website, a newsletter, and a group meeting, as well as educational events. The study compared those who participated in this program as they transferred from pediatric to adult care (younger group) and those who had access to the program 1–7 years after transferring from pediatric to adult care (older group). The program was successful in reducing loss-to-follow-up for the younger group and in helping the older group reconnect with medical care. The younger group reported no long-term complications, while the older group reported some complications. Notably, Holmes-Walker and colleagues in Australia, as noted above, were the first to report use of a care coordinator to assist with easing the transition [39].

In Italy, Cadario and colleagues [53] retrospectively examined the transition process in 2 cohorts from 1994 to 2004. Two groups, at different time periods, were transitioned from pediatric to adult services differently. Group A was sent a letter detailing their clinical history, including an upcoming appointment with an adult diabetes doctor. Group B participated in structured transition planning. This program consisted of working with their medical team during the last year in the pediatric clinic and discussing expectations and clinical implications regarding the transition process. Patients in Group B were given individual help by a transition coordinator during the transition period and were also assured they could return to pediatric care if they did not want to stay in adult care. The last visit in the pediatric clinic was attended by the pediatrician and adult doctor and the pediatrician gave a medical summary to both the patient and the adult doctor. Additionally, the first visit in the adult clinic included the pediatric doctor.

This program included many aspects that are recommended by various professional guidelines; and, in fact, it was effective in improving follow-up and diabetes self-care. Length of time between last pediatric visit and first adult visit was shorter in Group B (P<0.01). One year and 3 years after the last pediatric visit, 100 % of the patients from Group B were still followed in the adult diabetes clinic. In addition, the first HbA1c in adult care was improved from the last year in pediatric care in Group B (P<0.01), but it did not differ in Group A. In addition, 1 year after the transition, HbA1c was lower in Group B than in Group A (P<0.05).

Young Adult Support Groups

More recently, we examined the utility of support groups for young adults with type 1 diabetes in the transition period [54•]. Participants, ages 18–30 years, attended monthly support groups for 5 months. We assessed HbA1c, diabetes-related burden (measured by the Problem Areas in Diabetes survey (PAID [55]), and diabetes self-care (measured by the Self-Care Inventory-R [SCI-R] [56]). Eighty percent of participants attended at least 3 group sessions; 53 % attended at least 4 sessions.

Scores on the PAID decreased significantly from pre- to post-group (_P_=0.02), indicating less diabetes-related burden after group participation. In addition, SCI-R scores increased from pre-group to post-group (pre: 63.6±12.3, post: 72.0±13.7; _P_=0.09), suggesting that participants increased their self-care behaviors. Electronic medical record review provided HbA1c data from the year prior to and the year after participation and revealed that 2/3 of participants demonstrated improvement in HbA1c. During the course of group participation, the young adults identified 3 themes important for discussion: 1) objective approaches to managing diabetes in day-to-day life; 2) subjective recollections of interactions with peers without diabetes and handling imperfections regarding diabetes care; and 3) emotions related to insecurities, concerns about imperfections in care, stress, anxiety, and sadness. These young adults sought diabetes care providers who were knowledgeable, supportive, responsive, and part of a multidisciplinary team. They valued open communication and sufficient interaction time.

Future Directions

A new initiative called “Let’s empower and prepare type 1 diabetes youth” (LEAP) in Southern California, funded by the Helmsley Trust, aims to support the transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care and reconnect those young adults who are lost to follow-up with regular medical care, with a focus on underinsured patients (http://leap-usc.com/) [57].

Taken together, these studies show that structured transition planning and processes work to improve outcomes in young adults with type 1 diabetes. However, randomized clinical trials are needed to test these transition programs in order to understand and develop a gold standard for helping pediatric patients make a successful transfer to adult care.

Conclusions

Emerging young adults with type 1 diabetes are at high risk for diabetes complications, due to non-adherence, suboptimal glycemic control, and loss-to-follow-up care [17••, 32, 58–64]. As these young adults face competing social, emotional, educational, occupational, and/or financial demands, coupled with decreasing parental support and fragmented care between pediatric and adult providers, adherence to self-care behaviors often declines, glycemic control then deteriorates, and risk for acute and chronic complications increases (Fig. 2) [21–24, 65–68].

Fig. 2.

Constellation of factors influencing healthcare transition in emerging young adults with type 1 diabetes. Multiple factors likely influence the success of healthcare transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care teams. A successful transition will lead to improved health outcomes. Additional research is needed to identify the optimal approaches to ensure a successful transition

In studies of youth with type 1 diabetes, adolescents with depression and disordered eating behaviors have poorer outcomes and increased rates of hospitalization [67, 69, 70]; this trajectory continues with physical and mental health problems as youth enter young adulthood [21–24, 71]. The British Diabetic Association Cohort Study [30, 72] documented that the relative risk of death was higher for young adults with diabetes than for those without diabetes. Thus, it is critically important to begin the process of transition with support for both the acquisition of self-care behaviors and ongoing follow-up diabetes care to optimize chances for long-term health for young persons with type 1 diabetes.

Recent reviews have highlighted a framework upon which to conceptualize the transition process for patients with type 1 diabetes [20•, 73, 74]. As multiple factors influence the transition process (Fig. 2), additional study is needed to uncover the relative importance of each factor and to consider opportunities to utilize new technologies such as social media and mobile applications to engage the older teen and young adult in self-care behaviors. Future research will be directed at the design, implementation, and evaluation of approaches to ensure a successful transition that avoids gaps in care and provides the necessary scaffolding to support the emerging young adult with type 1 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Conflicts of interest: K.C. Garvey: has received grant support from a K12 Career Development Grant (K12DK094721); J.T. Markowitz: has received grant support from the NIDDK (1K23DK092335) to investigate the transition from pediatric to adult care; L.M.B. Laffel: has received grant support from Bayer and is PI/Program Director of an NIH K12 Career Development Grant (K12DK094721); has received donations from Eleanor Chesterman Beatson Fund, Maria Griffin Drury Fund, and Katharine Adler Astrove Youth Education Fund; has been a consultant for Johnson and Johnson, Eli Lilly and Co., Sanofi-Aventis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Menarini, LifeScan/Anima, and Oshadi Administrative Devices.

Contributor Information

Katharine C. Garvey, Email: katharine.garvey@childrens.harvard.edu, Endocrinology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Jessica T. Markowitz, Email: jessica.markowitz@joslin.harvard.edu, Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Section, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, 1 Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Lori M. B. Laffel, Email: lori.laffel@joslin.harvard.edu, Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Section, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, 1 Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Dabelea D, Bell RA, D’Agostino RB, Jr, et al. Incidence of diabetes in youth in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liese AD, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Hamman RF, et al. The burden of diabetes mellitus among US youth: prevalence estimates from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1510–1518. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vehik K, Hamman RF, Lezotte D, et al. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes in 0- to 17-year-old Colorado youth. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:503–509. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabelea D, DeGroat J, Sorrelman C, et al. Diabetes in navajo youth: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S141–S147. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu LL, Yi JP, Beyer J, et al. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes in asian and pacific islander U.S. youth: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S133–S140. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, Reynolds K, et al. Diabetes in hispanic american youth: prevalence, incidence, demographics, and clinical characteristics: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S123–S132. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer-Davis EJ, Beyer J, Bell RA, et al. Diabetes in african american youth: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S112–S122. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell RA, Mayer-Davis EJ, Beyer JW, et al. Diabetes in non-hispanic white youth: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S102–S111. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harjutsalo V, Sjoberg L, Tuomilehto J. Time trends in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in Finnish children: a cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371:1777–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60765-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehehalt S, Dietz K, Willasch AM, Neu A. Baden-Wurttemberg Diabetes Incidence Registry (DIARY) Group. Epidemiological perspectives on type 1 diabetes in childhood and adolescence in Germany:20 years of the Baden-Wurttemberg Diabetes Incidence Registry (DIARY) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:338–340. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence JM, Bell RA, Dabelea D, et al. Trends in incidence of type 1 diabetes among non-hisptanic white (NHW) youth in the US: 2002–2009. Diabetes. 2012;61:A52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer-Davis E, Dabelea D, Talton JW, et al. Increase in prevalence of type 1 diabetes from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study: 2001 to 2009 [Abstract] Diabetes. 2012;61:A322. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petitti DB, Klingensmith GJ, Bell RA, et al. Glycemic control in youth with diabetes: the SEARCH for diabetes in Youth Study. J Pediatr. 2009;155:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters A, Laffel L. The American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group. Diabetes care for emerging adults: recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care systems. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2477–2485. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1723. These consensus guidelines for health care transition in type 1 diabetes were published by the American Diabetes Association in 2011 and encompass representation from many other professional societies.

- 18.Sparud-Lundin C, Ohrn I, Danielson E. Redefining relationships and identity in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:128–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen B, Ward G, Jenkins A, King SJ, Dunning T. Young adults’ management of Type 1 diabetes during life transitions. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1981–1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanna KM. A framework for the youth with type 1 diabetes during the emerging adulthood transition. Nurs Outlook. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.10.005. This new review article provides a comprehensive examination of the developmental challenges of emerging adulthood in the setting of health care transition in type 1 diabetes.

- 21.Wysocki T, Hough BS, Ward KM, Green LB. Diabetes mellitus in the transition to adulthood: adjustment, self-care, and health status. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryden KS, Peveler RC, Stein A, Neil A, Mayou RA, Dunger DB. Clinical and psychological course of diabetes from adolescence to young adulthood: a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1536–1540. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, Peveler RC, Neil HA. Poor prognosis of young adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1052–1057. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Insabella G, Grey M, Knafl G, Tamborlane W. The transition to young adulthood in youth with type 1 diabetes on intensive treatment. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8:228–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feltbower RG, Bodansky HJ, Patterson CC, et al. Acute complications and drug misuse are important causes of death for children and young adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the Yorkshire register of diabetes in children and young adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:922–926. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White PH, McManus MA, McAllister JW, Cooley WC. A primary care quality improvement approach to health care transition. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41:e1–e7. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120426-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen DS, Blum RW, Britto M, Sawyer SM, Siegel DM. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Academy of Pediatrics AAoFPa. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128:182–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, et al. The British Diabetic Association Cohort Study, I: all-cause mortality in patients with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1999;16:459–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Willett JB, et al. Psychological adjustment to IDDM 10-year follow-up of an onset cohort of child and adolescent patients. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:811–818. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson AM, Hauser ST, Willett J, Wolfsdorf JI, Herman L. Consequences of irregular vs continuous medical follow-up in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 1997;131:727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wills CJ, Scott A, Swift PG, Davies MJ, Mackie AD, Mansell P. Retrospective review of care and outcomes in young adults with type 1 diabetes. BMJ. 2003;327:260–261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joergensen C, Hovind P, Schmedes A, Parving HH, Rossing P. Vitamin D levels, microvascular complications, and mortality in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1081–1085. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank M. Factors associated with non-compliance with a medical follow-up regimen after discharge from a pediatric diabetes clinic. Can J Diabetes. 1996;20:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pacaud D, McConnell B, Huot C, Aebi C, Yale JF. Transition from pediatric to adult care for insulin-dependent diabetes patients. Can J Diabetes. 1996;20:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pacaud D, Yale JF, Stephure D, Dele-Davies H. Problems in transition from pediatric care to adult care for individuals with diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2005;40:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garvey KC, Wolpert HA, Rhodes ET, et al. Health care transition in patients with type 1 diabetes: young adult experiences and relationship to glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(8):1716–1722. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2434. This is the largest cross-sectional study to date describing the health care transition experiences as reported by emerging adults with type 1 diabetes in the United States. Associations are examined between transition preparation, gaps between pediatric and adult diabetes care, and glycemic control.

- 39.Holmes-Walker DJ, Llewellyn AC, Farrell K. A transition care program which improves diabetes control and reduces hospital admission rates in young adults with type 1 diabetes aged 15–25 years. Diabet Med. 2007;24:764–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mainous AG, III, Koopman RJ, Gill JM, Baker R, Pearson WS. Relationship between continuity of care and diabetes control: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:66–70. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, et al. Current methods of transfer of young people with Type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet Med. 2002;19:649–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busse FP, Hiermann P, Galler A, et al. Evaluation of patients’ opinion and metabolic control after transfer of young adults with type 1 diabetes from a pediatric diabetes clinic to adult care. Horm Res. 2007;67:132–138. doi: 10.1159/000096583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sparud-Lundin C, Ohrn I, Danielson E, Forsander G. Glycaemic control and diabetes care utilization in young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakhla M, Daneman D, To T, Paradis G, Guttmann A. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: findings from a Universal Health Care System. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1134–e1141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0041. This database study describes the largest observation of transitioning patients with type 1 diabetes reported to date (1507 patients). Rates of pre- and post-transition diabetes-related hospitalizations as well as retinal examinations are reported.

- 45.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(Suppl 1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neu A, Losch-Binder M, Ehehalt S, Schweizer R, Hub R, Serra E. Follow-up of adolescents with diabetes after transition from pediatric to adult care: results of a 10-year prospective study 9. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:353–355. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dovey-Pearce G, Hurrell R, May C, Walker C, Doherty Y. Young adults’ (16–25 years) suggestions for providing developmentally appropriate diabetes services: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Visentin K, Koch T, Kralik D. Adolescents with type 1 diabetes: transition between diabetes services. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:761–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orr DP, Fineberg NS, Gray DL. Glycemic control and transfer of health care among adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18:44–47. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00044-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lane JT, Ferguson A, Hall J, et al. Glycemic control over 3 years in a young adult clinic for patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Logan J, Peralta E, Brown K, Moffett M, Advani A, Leech N. Smoothing the transition from paediatric to adult services in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Nurs. 2008;12:328–338. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Walleghem N, Macdonald CA, Dean HJ. Evaluation of a systems navigator model for transition from pediatric to adult care for young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1529–1530. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cadario F, Prodam F, Bellone S, et al. Transition process of patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) from pediatric to the adult health care service: a hospital-based approach. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:346–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markowitz JT, Laffel LM. Transitions in care: support group for young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29:522–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03537.x. This is a recent study showing an important model for young adult support during the period of transition. Participation in a young adult support group for patients with type 1 diabetes was associated with decreased self-reported diabetes burden and improvements in diabetes self care.

- 55.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754–760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinger K, Butler HA, Welch GW, La Greca AM. Measuring diabetes self-care: a psychometric analysis of the Self-Care Inventory-Revised with adults. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1346–1352. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sequeira PA, Weigensberg M, Pyatak B, et al. Emergency healthcare utilization for young adults (YA) with type 1 diabetes (T1D) who have aged out of pediatric healthcare. Diabetes. 2012;61(Suppl 1):A323. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. J Pediatr. 1994;125:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The DCCT Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krolewski AS, Warram JH, Christlieb AR, Busick EJ, Kahn CR. The changing natural history of nephropathy in type I diabetes. Am J Med. 1985;78:785–794. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borch-Johnsen K, Kreiner S, Deckert T. Diabetic nephropathy–susceptible to care? A cohort-study of 641 patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetes Res. 1986;3:397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobson AM, Adler AG, Derby L, Anderson BJ, Wolfsdorf JI. Clinic attendance and glycemic control. Study of contrasting groups of patients with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:599–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawahara R, Amemiya T, Yoshino M, Miyamae M, Sasamoto K, Omori Y. Dropout of young non-insulin-dependent diabetics from diabetic care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;24:181–185. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kurlander JE, Kerr EA, Krein S, Heisler M, Piette JD. Cost-related nonadherence to medications among patients with diabetes and chronic pain: factors beyond finances. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2143–2148. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Svensson M, Sundkvist G, Arnqvist HJ, et al. Signs of nephropathy may occur early in young adults with diabetes despite modern diabetes management: results from the nationwide population-based diabetes incidence study in Sweden (DISS) Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2903–2909. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hillier TA, Pedula KL. Complications in young adults with early-onset type 2 diabetes: losing the relative protection of youth. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2999–3005. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rydall AC, Rodin GM, Olmsted MP, Devenyi RG, Daneman D. Disordered eating behavior and microvascular complications in young women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1849–1854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayer-Davis EJ, Ma B, Lawson A, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in youth with type1 and type2 diabetes: implications of a factor analysis of clustering. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:89–95. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rewers A, Chase HP, Mackenzie T, et al. Predictors of acute complications in children with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2002;287:2511–2518. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGrady ME, Laffel L, Drotar D, Repaske D, Hood KK. Depressive symptoms and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: mediational role of blood glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:804–806. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goebel-Fabbri AE, Fikkan J, Franko DL, Pearson K, Anderson BJ, Weinger K. Insulin restriction and associated morbidity and mortality in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:415–419. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, et al. The British Diabetic Association Cohort Study, II: cause-specific mortality in patients with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1999;16:466–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weissberg-Benchell J, Wolpert H, Anderson BJ. Transitioning from pediatric to adult care: a new approach to the post-adolescent young person with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2441–2446. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolpert HA, Anderson BJ, Weissberg-Benchell J. Transitions in care: meeting the challenges of type 1 diabetes in young adults. American Diabetes Association. 2009 [Google Scholar]