Structures of Cas9 Endonucleases Reveal RNA-Mediated Conformational Activation (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Oct 3.

Published in final edited form as: Science. 2014 Feb 6;343(6176):1247997. doi: 10.1126/science.1247997

Abstract

Type II CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)–Cas (CRISPR-associated) systems use an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease, Cas9, to generate double-strand breaks in invasive DNA during an adaptive bacterial immune response. Cas9 has been harnessed as a powerful tool for genome editing and gene regulation in many eukaryotic organisms. We report 2.6 and 2.2 angstrom resolution crystal structures of two major Cas9 enzyme subtypes, revealing the structural core shared by all Cas9 family members. The architectures of Cas9 enzymes define nucleic acid binding clefts, and single-particle electron microscopy reconstructions show that the two structural lobes harboring these clefts undergo guide RNA–induced reorientation to form a central channel where DNA substrates are bound. The observation that extensive structural rearrangements occur before target DNA duplex binding implicates guide RNA loading as a key step in Cas9 activation.

Bacteria and archaea target invasive DNA using RNA-guided adaptive immune systems encoded by CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)–Cas (CRISPR-associated) genomic loci (1–4). After integration of short fragments of invader-derived DNA into a CRISPR array within the host chromosome (5), enzymatic processing of CRISPR transcripts produces mature CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) that direct Cas protein–mediated targeting of DNA bearing complementary sequences (protospacers) to foreign nucleic acids (6). Although type I and III CRISPR-Cas systems rely on multiprotein complexes for crRNA-guided DNA targeting (1, 4, 7), type II systems use a single RNA-guided endonuclease, Cas9, that requires both a mature crRNA and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) for target DNA recognition and cleavage (8, 9). Both a seed sequence in the crRNA and conserved protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence in the target are crucial for Cas9-mediated cleavage (8, 10).

Cas9 proteins are abundant across the bacterial kingdom, but vary widely in both sequence and size. All known Cas9 enzymes contain an HNH domain that cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA sequence (target strand), and a RuvC nuclease domain required for cleaving the noncomplementary strand (non-target strand), yielding double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) (8, 10). In addition, Cas9 enzymes contain a highly conserved arginine-rich (Arg-rich) region previously suggested to mediate nucleic acid binding (11). On the basis of CRISPR-Cas locus architecture and protein sequence phylogeny, Cas9 genes cluster into three subfamilies: types II-A, II-B, and II-C (12, 13). Cas9 proteins found in II-A and II-C subfamilies typically contain ~1400 and ~1100 amino acids, respectively.

The ability to program Cas9 for DNA cleavage at specific sites defined by guide RNAs has led to its adoption as a versatile platform for genome engineering (14). When directed to target loci in eukaryotes by either dual crRNA:tracrRNA guides or chimeric single-guide RNAs, Cas9 generates site-specific DSBs that are repaired either by nonhomologous end joining or by homologous recombination (15–17), which can be exploited to modify genomic sequences in the vicinity of the Cas9-generated DSBs. Furthermore, catalytically inactive Cas9 alone or fused to transcriptional activation or repression domains can be used to control transcription at sites defined by guide RNAs (18–20). Both type II-A and type II-C Cas9 proteins have been used in eukaryotic genome editing (21, 22). Smaller Cas9 proteins, encoded by more compact genes, are potentially advantageous for cellular delivery using vectors that have limited size such as adeno-associated virus and lentivirus.

Here, we present the crystal structures of Cas9 enzymes from the two major enzyme subclasses (type II-A and type II-C). Both structures reveal the fundamental RNA-guided DNA endonuclease architecture, the locations of both active sites, and the likely nucleic acid binding clefts. Biochemical experiments show that PAM recognition occurs through a composite binding site that is disordered in the absence of guide RNA and substrate interactions. Single-particle electron microscopy (EM) structures show that guide RNA loading triggers a conformational change in Cas9 for productive DNA surveillance. Together, these data provide insights into the function, regulation, and evolution of the Cas9 enzyme family.

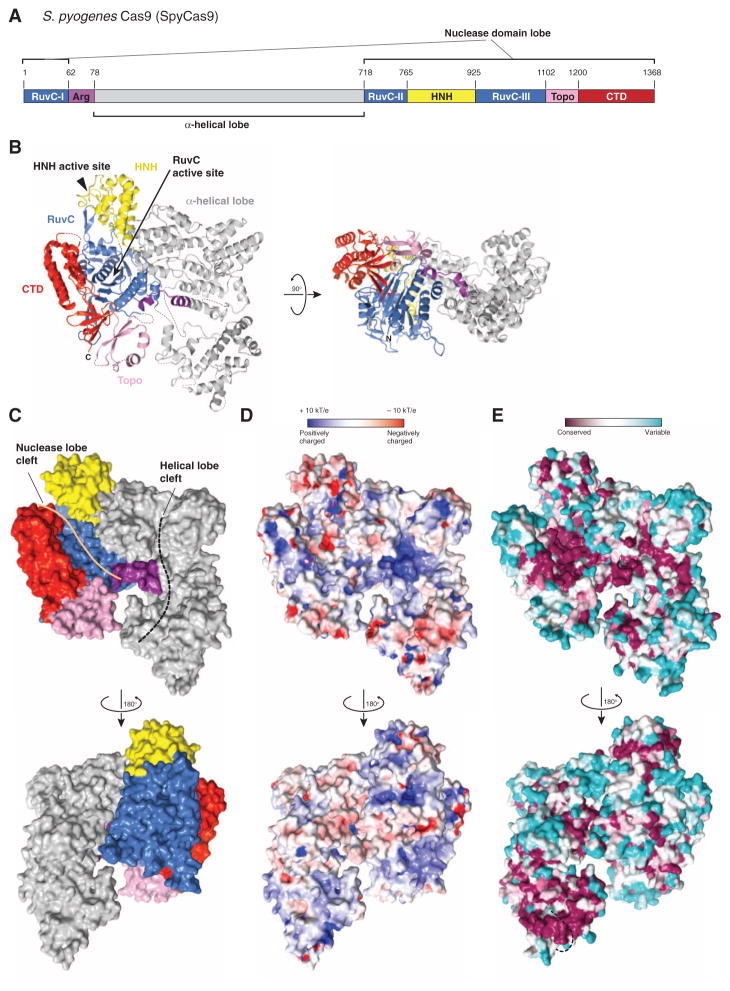

Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 Structure Reveals a Two-Lobed Architecture with Adjacent Active Sites

Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpyCas9) is a prototypical type II-A Cas9 protein consisting of well-conserved RuvC and HNH domains, and flanking regions lacking apparent sequence similarity to known protein structures (Fig. 1A). As the first biochemically characterized Cas9, SpyCas9 is used in most of the current CRISPR-based genetic engineering methodologies (14). To obtain structural insights into the architecture of SpyCas9, we determined the 2.6-Å resolution crystal structure of the enzyme (Table 1). The structure reveals that SpyCas9 is a crescent-shaped molecule with approximate dimensions of 100 Å × 100 Å × 50 Å (Fig. 1B and fig. S1). The enzyme adopts a distinct bilobed architecture comprising the nuclease domains and the C-terminal domain in one lobe (the nuclease lobe), and a large α-helical domain in the other. The RuvC domain forms the structural core of the nuclease lobe, a six-stranded β sheet surrounded by four α helices, with all three conserved motifs contributing catalytic residues to the active site (fig. S1). The HNH and RuvC domains are juxtaposed in the SpyCas9 structure, with their active sites located ~25 Å apart. The HNH domain active site is poorly ordered in apo-SpyCas9 crystals, suggesting that the active site may undergo conformational ordering upon nucleic acid binding. The C-terminal region of SpyCas9 contains a β-β-α-β Greek key domain that bears structural similarity to a domain found in topoisomerase II (23) (hereafter referred to as the Topo-homology domain, residues 1136Spy to 1200Spy). A mixed α/β region (C-terminal domain, residues 1201Spy to 1363Spy) forms a protrusion on the nuclease domain lobe. The structural halves of SpyCas9 are connected by two linking segments, one formed by the Arg-rich region (residues 59Spy to 76Spy) and the other by a disordered linker comprising residues 714Spy to 717Spy (Fig. 1B). The total surface area buried between the two structural lobes in SpyCas9 is 1034 Å2.

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of SpyCas9 reveals an open bilobed architecture and nucleic acid binding clefts.

(A) Cartoon schematic of the polypeptide sequence and domain organization for the type II-A Cas9 protein from S. pyogenes (SpyCas9). Cas9 is predicted to contain a single HNH nuclease domain and a single RuvC nuclease domain. The RuvC domain is made up of three discontinuous segments (RuvC-I to RuvC-III), with the α-helical lobe inserted between the first and the second segments, and the HNH domain inserted between the second and the third segments. Arg, arginine-rich region; Topo, Topo-homology domain; CTD, C-terminal domain. (B) Orthogonal views of the overall structure of SpyCas9 shown in ribbon representation. Individual Cas9 domains are colored according to the scheme in (A). SpyCas9 consists of a nuclease domain lobe and an α-helical lobe. Disordered segments of the polypeptide chain are denoted with dotted lines. (C) Surface representation of SpyCas9 depicting the two nucleic acid binding clefts on the molecular surface. (D) Surface electrostatic potential map of SpyCas9 colored from −10 kT/e (red) to +10 kT/e (blue) (61). (E) Surface representation of SpyCas9 colored according to evolutionary conservation. The representation was generated using the ConSurf server (62) based on the multiple sequence alignment of type II-A Cas9 proteins shown in fig. S1. A disordered segment (residues 571Spy to 586Spy, indicated with a black dashed line) covers the apparently conserved patch on the reverse convex surface of SpyCas9.

Table 1.

X-ray data collection, refinement, and model statistics for SpyCas9.

| Data set | Native | MnCl2 soak | SeMet | Sodium tungstate | CoCl2 soak | Er(III) acetate soak | Thimerosal soak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray source | SLS PXI | SLS PXIII | ALS 8.2.2 | SLS PXI | SLS PXIII | ALS 8.2.2 | SLS PXIII |

| Space group | _P_21212 | _P_21212 | _P_21212 | _P_21212 | _P_21212 | _P_21212 | _P_21212 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 159.8, 209.6, 91.3 | 159.8, 209.3, 91.0 | 158.9, 201.1, 89.7 | 160.0, 209.5, 90.5 | 161.3, 210.9, 91.0 | 159.5, 209.2, 90.9 | 159.5, 209.1, 90.5 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.979168 | 1.2149 | 1.58955 | 1.475991 | 1.00392 |

| Resolution (Å)* | 127.07–2.62 (2.69–2.62) | 47.48–3.10 (3.18–3.10) | 87.64–4.20 (4.31–4.20) | 49.77–3.90 (4.00–3.90) | 47.9–3.60 (3.69–3.60) | 87.45–3.30 (3.39–3.30) | 47.38–3.59 (3.69–3.59) |

| _R_sym (%)* | 4.7 (63.6) | 9.6 (94.0) | 15.2 (71.4) | 12.2 (87.0) | 8.6 (76.3) | 6.7 (39.7) | 19.4 (78.8) |

| I/σ_I_* | 13.02 (1.94) | 19.1 (2.3) | 9.7 (2.9) | 17.3 (4.1) | 14.2 (3.0) | 10.4 (2.1) | 10.4 (2.5) |

| Completeness (%)* | 98.2 (98.5) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.8) | 99.9 (99.9) | 100.0 (100.0) | 98.4 (99.4) | 99.4 (92.8) |

| Redundancy* | 2.3 (2.3) | 7.1 (7.3) | 6.0 (6.0) | 14.0 (14.1) | 7.1 (7.0) | 2.1 (2.1) | 7.0 (5.9) |

| Refinement | |||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 47.52–2.62 | 47.53–3.09 | |||||

| No. of reflections | 92,408 | 56,200 | |||||

| _R_work/_R_free | 0.253/0.286 | 0.252/0.278 | |||||

| No. of atoms | |||||||

| Protein | 18,892 | 18,862 | |||||

| Ion | 26 | 43 | |||||

| Water | 203 | 0 | |||||

| _B_-factors | |||||||

| Mean | 62.6 | 62.3 | |||||

| Protein | 62.8 | 62.2 | |||||

| Ion | 68.8 | 79.1 | |||||

| Water | 45.8 | 91.8 | |||||

| Root mean square deviation | |||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.004 | |||||

| Bond angles (°) | 0.95 | 0.74 | |||||

| Ramachandran plot | |||||||

| % Favored | 96.2 | 97.6 | |||||

| % Allowed | 3.8 | 2.4 | |||||

| % Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| MolProbity | |||||||

| Clashscore | 10.3 | 8.2 |

SpyCas9 Contains Two Putative Nucleic Acid Binding Grooves

SpyCas9 contains two prominent clefts on one face of the molecule: a deep and narrow groove located within the nuclease lobe and a somewhat wider groove within the α-helical lobe (Fig. 1C). The nuclease lobe cleft is about 40 Å long, 15 to 20 Å wide, and 15 Å deep, with the RuvC active site located at its bottom. The C-terminal domain forms one side of the cleft, whereas the HNH domain and a protrusion of the α-helical lobe form the other. The concave surface of the α-helical lobe creates a wider, shallower groove that extends over almost its entire length (Fig. 1C). The groove is more than 25 Å across at its widest point, which would be sufficient to accommodate an RNA-RNA or DNA-RNA duplex. Its surface is highly positively charged (Fig. 1D), especially at the Arg-rich segment comprising R69Spy, R70Spy, R71Spy, R75Spy, and K76Spy. Multiple sulfate or tungstate ions are bound to the α-helical lobe in the SpyCas9 crystals (fig. S2), hinting at a possible role in nucleic acid binding. Amino acid residues located in both the nuclease and α-helical lobe clefts are highly conserved within type II-A Cas9 proteins (Fig. 1E), suggesting that both clefts play important functional roles. Because the RuvC domain mediates cleavage of the nontarget DNA strand (8, 10), the nuclease domain cleft likely binds the displaced nontarget strand. Conversely, the α-helical lobe, which contains the Arg-rich segment, might be involved in binding the crRNA:tracrRNA guide RNA and/or the crRNA–target DNA hetero-duplex. This would be consistent with the observation that a mutation in the Arg-rich region in Francisella novicida Cas9 leads to loss of RNA-guided targeting in vivo (11).

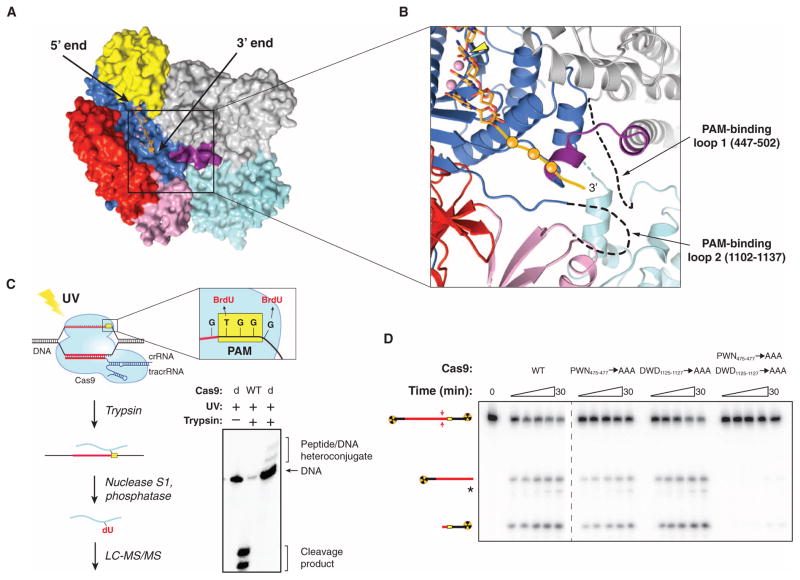

PAM Recognition by SpyCas9 Involves Two Tryptophan-Containing Flexible Loops

SpyCas9 recognizes a 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequence located 3 base pairs (bp) to the 3′ side of the cleavage site on the noncomplementary DNA strand, whereas other Cas9 orthologs have different PAM requirements (8, 10, 22, 24–27). To gain insight into PAM binding by SpyCas9, we superimposed the SpyCas9 RuvC nuclease domain structure with that of the RuvC Holliday junction resolvase–substrate complex (28) (fig. S3A), which enabled us to model the likely trajectory of the nontarget DNA strand in the SpyCas9 holoenzyme (Fig. 2A and fig. S3, B and C). The DNA strand is located along the length of the nuclease lobe cleft in an orientation that would position the 3′ end of the DNA, and hence the PAM, at the junction of the two lobes, in the vicinity of the Arg-rich segment and the Topo-homology domain (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Cross-linking identifies a PAM binding region adjacent to the active-site cleft.

(A) Model of noncomplementary DNA strand bound to the RuvC domain based on a superposition with the DNA-bound complex of Thermus thermophilus RuvC Holliday junction resolvase [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 4LD0]. The modeled DNA strand contains three nucleotides upstream and three nucleotides downstream of the scissile phosphate. Divalent ions in the RuvC active site are depicted as pink spheres. (B) Zoomed-in view of the RuvC cleft showing the modeled nontarget DNA strand (stick format, scissile phosphate indicated with yellow arrowhead) and the predicted path of the downstream (3′) sequence containing the PAM (orange ball and string). Disordered loops identified by cross-linking are denoted with dashed lines. (C) Cartoon (left) showing the design and workflow of cross-linking experiments with DNA substrates containing BrdU nucleotides for LC-MS/MS analysis. The guide/target sequence is depicted in red, and the PAM is highlighted in yellow. The denaturing polyacrylamide gel (right) demonstrates the generation of covalent peptide-DNA adducts with catalytically inactive SpyCas9 (dCas9) after UV irradiation and trypsin digestion. (D) DNA cleavage activity assays with SpyCas9 constructs containing mutations in residues identified by cross-linking and LC-MS/MS experiments. The asterisk denotes trimming of the nontarget strand.

To directly identify regions of Cas9 involved in PAM binding, we reconstituted catalytically inactive SpyCas9 (D10A/H840A) with a crRNA: tracrRNA guide RNA and bound it to DNA targets carrying a photoactivatable 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) nucleotide adjacent to either end of the GG PAM motif on the nontarget strand (Fig. 2C). After ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and trypsin digestion, covalent peptide-DNA cross-links were detected (Fig. 2C and fig. S4). A DNA substrate containing BrdU on the target strand opposite the PAM failed to produce a cross-link (fig. S4). After nuclease and phosphatase digestion of cross-linked DNA, nano–high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) was performed to identify tryptic peptides containing covalent dU or p-dU adducts (Fig. 2C and figs. S5 and S6). The nucleotide immediately 5′ to the GG motif cross-linked to residue W476Spy, whereas the residue immediately 3′ to the motif cross-linked to residue W1126Spy (figs. S5 and S6). Both tryptophans are located in disordered regions of SpyCas9 located ~30 Å apart. W476Spy resides in a 53–amino acid loop at the edge of the α-helical lobe underneath the Arg-rich region, whereas W1126Spy is located in a 33–amino acid loop connecting the RuvC and Topo-homology domains (Fig. 2B). These tryptophan residues are conserved among type II-A Cas9 proteins that use the same NGG PAM to cleave target DNA in vitro (8, 27), but are absent from type II-C Cas9 proteins, which are known to recognize different PAMs (22, 25–27) (figs. S1 and S7). The type II-B Cas9 protein from F. novicida, whose PAM was recently shown to be 5′-NG-3′, contains a tryptophan (W501Fno) at the position corresponding to W476Spy, but lacks an aromatic residue equivalent to W1126Spy (27).

To test the roles of both loops in DNA target recognition and cleavage, we made triple alanine substitutions of residues 475Spy to 477Spy (P-W-N) and 1125Spy to 1127Spy (D-W-D) and performed cleavage assays with double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) targets (Fig. 2D and fig. S8). SpyCas9 mutated in residues 1125Spy to 1127Spy showed wild-type cleavage activity, whereas mutations in residues 475Spy to 477Spy caused a subtle, but reproducible, decrease in activity (fig. S9). Remarkably, mutating both loops simultaneously almost completely abolished SpyCas9 activity, indicating that at least one tryptophan-containing segment is necessary to promote DNA cleavage (Fig. 2D and fig. S10). The distance of both tryptophan residues from either nuclease domain argues against their direct catalytic role in DNA cleavage, instead suggesting that the residues are involved in PAM recognition. Consistent with this, DNA binding assays showed that each triple-mutant protein is moderately defective in DNA binding, whereas the dual triple-mutant protein has markedly reduced DNA binding affinity (fig. S11).

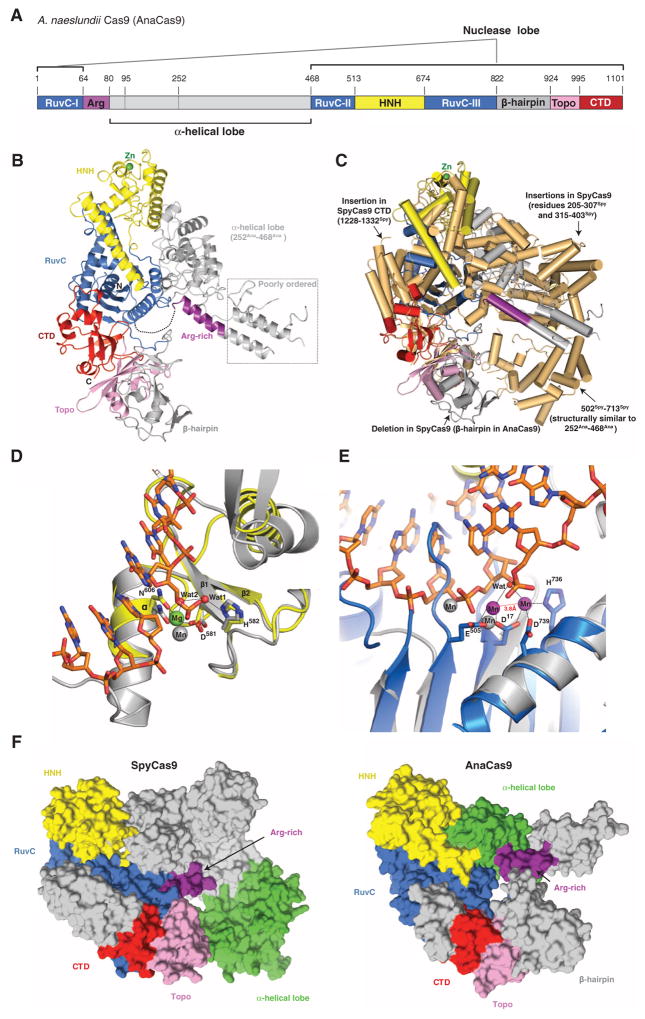

Actinomyces naeslundii Cas9 Structure Reveals the Architecture of a Smaller Cas9 Variant

Although most genome engineering methodologies currently use SpyCas9, there is considerable interest in exploiting more compact Cas9 enzymes for such applications (21, 22). To understand how the large and small Cas9 variants are related and how they carry out similar catalytic functions, we determined the 2.2-Å resolution crystal structure of the type II-C Cas9 enzyme from Actinomyces naeslundii (AnaCas9) (Table 2). AnaCas9 also folds into a bilobed structure with approximate dimensions of 105 Å × 80 Å × 55 Å. The RuvC and HNH nuclease domains, a Topo-homology domain, and the C-terminal domain form an extended nuclease lobe with the RuvC domain located at its center (Fig. 3, A and B). Similar to SpyCas9, the RuvC and HNH domains comprise a compact catalytic core, with the two active sites positioned ~30 Å apart. In contrast to SpyCas9, an additional domain (residues 822Ana to 924Ana, hereafter referred to as the β-hairpin domain) is found between the RuvC and Topo-homology domains, and adopts a novel fold composed primarily of three antiparallel β-hairpins. As in SpyCas9, the polypeptide sequence found between the RuvC-I and RuvC-II motifs forms an α-helical lobe. However, the AnaCas9 α-helical lobe is much smaller, and its orientation relative to the nuclease lobe is different (Fig. 3C and fig. S12, A to C). Comparison of the helical lobes in AnaCas9 and SpyCas9 reveals that regions 95Ana to 251Ana and 77Spy to 447Spy are highly divergent and do not align in sequence and structure (fig. S7). Moreover, the 95Ana to 251Ana region is poorly ordered (fig. S13A), and only parts of it could be modeled. By contrast, residues 252Ana to 468Ana and 502Spy to 713Spy, which share ~32% sequence identity, superimpose well with a root mean square deviation of ~3.6 Å over 149 Cα atoms (Fig. 3C and fig. S12, A to H). Intriguingly, the position and orientation of this portion of the α-helical domain with respect to the RuvC domain in the AnaCas9 and SpyCas9 structures are substantially different, with a large displacement of ~70 Å toward the RuvC domain and an about 35° rotation about the junction between two domains in AnaCas9 (fig. S12C).

Table 2.

X-ray data collection, refinement, and model statistics for AnaCas9.

| Data set | SeMet | Native | Mn soak |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray source | ALS 8.3.1 | ALS 8.3.1 | ALS 8.2.2 |

| Space group | _P_1 21 1 | _P_1 21 1 | _P_1 21 1 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 74.58, 133.09, 80.17 | 75.415, 133.025, 80.69 | 74.61, 132.56, 80.04 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 95.79, 90.00 | 90, 96.22, 90 | 90, 95.38, 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.978 | 1.116 | 1.000 |

| Resolution (Å)* | 79.76–3.19 (3.37–3.19) | 80.2–2.2 (2.32–2.2) | 79.69–2.80 (2.95–2.80) |

| _R_merge (%)* | 0.124 (0.428) | 0.096 (0.795) | 0.090 (0.628) |

| _R_pim† | 0.05 (0.176) | 0.029 (0.322) | 0.05 (0.358) |

| I/σ_I_* | 11.9 (4.6) | 14.89 (2.24) | 10.86 (2.27) |

| Completeness (%)* | 99.9 (99.7) | 98.0 (86.8) | 99.98 (100.00) |

| Redundancy* | 7.9 (7.8) | 8.6 (5.8) | 4.0 (4.0) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 68.0–2.2 | 68.3–2.8 (2.9–2.8) | |

| No. of reflections | 78,398 | 38,217 | |

| _R_work/_R_free | 0.1867/0.2281 | 0.1941/0.2310 | |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 7693 | 6888 | |

| Ligands | 24 | 27 | |

| Water | 348 | 4 | |

| _B_-factors | |||

| Mean | 57.9 | 67.3 | |

| Protein | 58.6 | 67.3 | |

| Ion | 52.2 | 64.9 | |

| Water | 42.01 | 42.7 | |

| Root mean square deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.005 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.22 | 0.84 | |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| % Favored | 94.00 | 95.00 | |

| % Allowed | 5.80 | 4.77 | |

| % Outliers | 0.20 | 0.23 | |

| MolProbity | |||

| Clashscore | 9.8 | 6.2 |

Fig. 3. Crystal structure of AnaCas9 defines the conserved structural core of Cas9 enzymes.

(A) Cartoon schematic of the polypeptide sequence and domain organization for the type II-C Cas9 protein from A. naeslundii (AnaCas9). (B) Overall structure of AnaCas9 shown in ribbon representation. Individual Cas9 domains are colored according to the scheme in (A). A disordered segment connecting a RuvC motif and Arg-rich region is denoted with a dashed line. The disordered region in the helical lobe is denoted with a dotted line box. A green sphere denotes a bound zinc ion in the HNH domain. (C) Superposition of AnaCas9 [colored as in (A)] with SpyCas9 (colored light orange). (D) Close-up view of the active site of AnaCas9 HNH domain (yellow) superimposed with the structure of I-HmuI–DNA complex (PDB entry 1U3E). The DNA cleavage product in the I-HmuI–DNA complex is colored orange, and I-HmuI and its bound Mn2+ ion are colored gray. (E) Close-up view of the AnaCas9 RuvC active site (marine, bound Mn2+ ions shown as purple spheres) overlaid with the structure of RNase H and its bound Mn2+ ions (gray) complexed with a DNA-RNA duplex (orange) (PDB entry 3O3H). (F) Surface representations of SpyCas9 (left panel) and AnaCas9 (right panel) with conserved RuvC, HNH, Arg-rich, Topo-homology, and the conserved cores of the C-terminal domains, colored as in Fig. 1A. The structurally preserved portion of the α-helical lobe is colored green. The nonconserved regions of each protein are colored in gray.

The higher resolution of the AnaCas9 structure provides insights into active-site chemistries for both nuclease domains. The well-defined AnaCas9 HNH domain contains a two-stranded antiparallel β sheet flanked by two α helices on each side, as well as a nonconserved noncatalytic zinc binding site (Fig. 3C and fig. S13B). The HNH active site reveals D581Ana and N606Ana coordinating a hydrated magnesium ion that would be involved in binding the scissile phosphate in the target DNA strand (Fig. 3D), and the general base residue H582Ana (corresponding to H840Spy) involved in deprotonating the attacking water nucleophile, in agreement with a one–metal ion catalytic mechanism for the endonucleases containing the ββα metal motif (29). In the RuvC domain, two Mn2+ ions, spaced 3.8 Å apart and coordinated by the invariant residues D17Ana, E505Ana, H736Ana, and D739Ana, are consistent with a two–metal ion mechanism, as observed in other nucleases containing the ribonuclease (RNase) H fold (Fig. 3E) (30, 31).

A Common Cas9 Functional Core Suggests Structural Plasticity that Supports RNA-Guided DNA Cleavage

Comparison of the SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 structures reveals a conserved functional core consisting of the RuvC and HNH domains, the Arg-rich region, and the Topo-homology domain, with divergent C-terminal and α-helical domains (Fig. 3F). In both SpyCas9 and AnaCas9, the Arg-rich region connects the nuclease and helical lobes of the proteins. The central position of the Arg-rich segment and its proximity to the PAM binding loops in SpyCas9 suggest that this region may be involved in guide RNA and/or target DNA binding and could function as a hinge to enable conformational rearrangements in the enzyme.

Although the helical lobes of SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 share a common region (residues 252Ana to 468Ana versus 502Spy to 713Spy), the orientation of this region relative to the nuclease lobe varies in the two structures (Fig. 3F). Differences between SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 thus illustrate the structural divergence likely responsible for the diversity of guide RNA structures and PAM specificities within the Cas9 superfamily. The PAM-interacting regions identified in SpyCas9 are located in loops that are highly variable within Cas9 enzymes (12, 13). In AnaCas9, the β-hairpin domain (residues 822Ana to 924Ana) is inserted at a position corresponding to one of the SpyCas9 PAM loops (1102Spy to 1136Spy), suggesting that AnaCas9 uses a distinct mechanism of PAM recognition (Fig. 3C and fig. S7). The β-hairpin domain is not conserved in all type II-C Cas9 proteins (figs. S7 and S14), further underscoring the notion that the sequence- and structure-divergent regions of Cas9 proteins may have co-evolved with specific guide RNA structures and PAM sequences (13, 27).

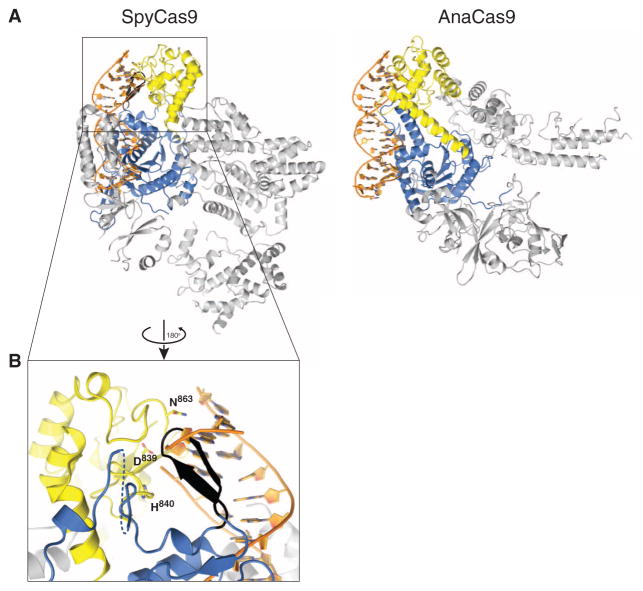

SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 Adopt Autoinhibited Conformations in the Apo State

Target DNA cleavage by Cas9 RuvC and HNH domains is thought to occur upon base pairing between the crRNA guide and the target DNA (8, 10, 32). Although SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 adopt distinct conformations in their helical lobes, the relative orientations of the RuvC and HNH active sites within the nuclease lobes are very similar (Fig. 3C and fig. S12). In both structures, the HNH active site faces outwards, away from the putative nucleic acid binding clefts (Figs. 1B and 4B). Structural superpositions with the DNA-bound complex of the HNH homing endonuclease I-HmuI (33) suggest that this orientation is unlikely to be compatible with target DNA binding and cleavage (Fig. 4A). In SpyCas9, the HNH domain active site is blocked by a β-hairpin formed by residues 1049Spy to 1059Spy of the RuvC domain. The RNA-DNA heteroduplex would additionally clash sterically with the C-terminal domain (Fig. 4, A and B). In AnaCas9, the bound crRNA–target DNA heteroduplex would conversely make few contacts with the protein outside of the HNH domain in the absence of HNH domain reorientation (Fig. 4A, right panel). The finding that two highly divergent Cas9 orthologs exhibit similar inactive states suggests that this may be a general property of Cas9 enzymes and not a consequence of crystallization. It is also consistent with the observation that Cas9 enzymes are inactive as nucleases in the absence of bound guide RNAs (8, 9). Together, these observations suggest that the enzymes undergo a conformational rearrangement upon guide RNA and/or target DNA binding.

Fig. 4. Both SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 adopt autoinhibited conformations in the apo state.

(A) Models of substrate binding by the HNH domains in SpyCas9 (left) and AnaCas9 (right), based on the superposition of the Cas9 structures with the product-bound complex of the homing endonuclease I-HmuI (PDB entry 1U3E). A 17-bp B-form DNA duplex that covers 3-bp 5′ and 14-bp 3′ of the scissile phosphate is shown. The Cas9 proteins are shown in the same orientation, based on superposition of the respective HNH domains. The HNH domains are depicted in yellow, the RuvC domains are depicted in blue, and residues 1049Spy to 1059Spy of the RuvC domain are shown in black. (B) Zoomed-in view of the HNH domain (yellow) active site in SpyCas9 occluded by the 1049Spy to 1059Spy β-hairpin (black).

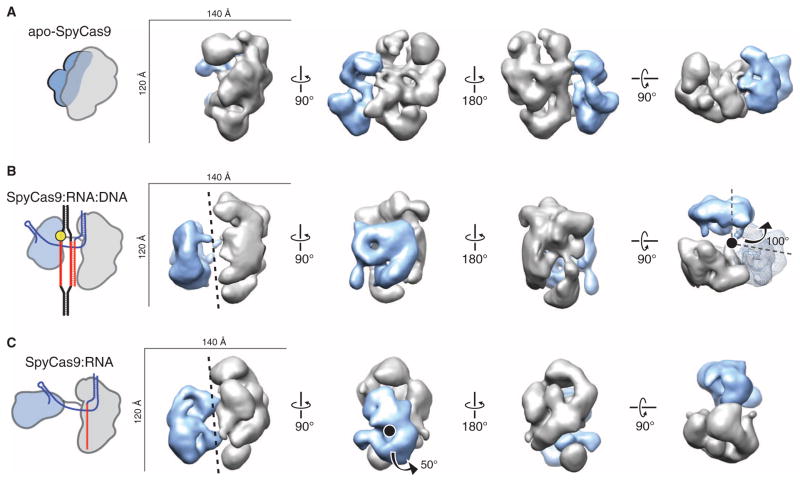

RNA Loading Rearranges the Two Lobes of SpyCas9 to Form a Central Channel

To visualize conformational states adopted by Cas9 upon guide RNA and target DNA binding, we determined the molecular architectures of SpyCas9 without guide RNA (apo-SpyCas9), in complex with crRNA:tracrRNA (SpyCas9:RNA), and bound to target DNA (SpyCas9:RNA:DNA) using negative-stain EM. Raw micrographs of the ~160-kD apo-SpyCas9 enzyme show monodisperse, globular particles with approximate dimensions of 120 Å × 140 Å, and two-dimensional (2D) reference-free class averages reveal that the enzyme has a two-lobed morphology in agreement with the crystal structure (fig. S15). We used the random conical tilt (RCT) method (34) to obtain an initial, ab initio 3D model of the complex (fig. S15). Using multiple refinement procedures (see Materials and Methods), we arrived at a final reconstruction of apo-SpyCas9 at ~19-Å resolution [using the 0.5 Fourier shell correlation (FSC) criterion] that reveals a clam-shaped morphology with one large, globular lobe connected to a smaller lobe (Fig. 5A). Using Situs (35), we were able to computationally dock the α-helical and nuclease domain lobes of the SpyCas9 crystal structure as rigid bodies into the larger and smaller lobes, with cross-correlation coefficients (CCCs) of 0.74 and 0.66, respectively (fig. S16 and table S1). To further support our lobe assignment, we generated a 3D reconstruction of Cas9 containing an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (N-MBP) fusion directly upstream of the RuvC-I motif; N-MBP–Cas9 retains full DNA cleavage activity (fig. S16). By 3D difference mapping, the additional density observed in this reconstruction was found to localize to the smaller lobe containing the RuvC nuclease domain (fig. S16).

Fig. 5. RNA loading positions the two major lobes of SpyCas9 around a central channel.

(A to C) Single-particle EM reconstructions of negatively stained apo-SpyCas9 (A), SpyCas9:RNA:DNA (B), and SpyCas9:RNA (C) at 19-, 19-, and 21-Å resolution (using the 0.5 FSC criterion), respectively. Cartoon representations of the structures are shown (left). The structures are aligned on the basis of the optimal CCCs between the independent α-helical lobes (gray). The smaller RuvC lobe (blue) in SpyCas9:RNA:DNA and SpyCas9:RNA rotates by ~100° [arrow in (B)] with respect to this lobe in the apo-Cas9 structure (transparent mesh) to form a central channel (black dashed line). There is a ~50° rotation [arrow in (C)] of the smaller lobe of SpyCas9:RNA along an axis perpendicular to this channel relative to SpyCas9:RNA:DNA.

We next prepared ribonucleoprotein complexes containing catalytically inactive D10A/H840A-SpyCas9 mutant, full-length crRNA:tracrRNA (SpyCas9:RNA), and bound these complexes to a 55-bp dsDNA substrate at substrate concentrations expected to saturate Cas9, given an equilibrium dissociation constant of ~4 nM (fig. S17). Reference-free 2D class averages of the DNA-bound complex (SpyCas9:RNA:DNA) hinted at a large-scale conformational change, with both lobes separating from one another into discrete structural units (fig. S17). Using the apo-SpyCas9 structure low-pass filtered to 60 Å as a starting model, we obtained a 3D reconstruction of SpyCas9:RNA:DNA at ~19 Å resolution (using the 0.5 FSC criterion) that further revealed a substantial reorganization of the major lobes (Fig. 5B). An independently determined ab initio 3D structure using the RCT method (34) yielded similar results (fig. S17). The shape of the larger lobe remains relatively unchanged from that in apo-Cas9 (CCC of 0.78), but the smaller lobe rotates by ~100° with respect to its position in the apo structure (Fig. 5B). An alternative model, assuming opposite handedness, also shows a large conformational change relative to the apo-Cas9 structure (fig. S18). A reconstruction of SpyCas9:RNA:DNA using the N-MBP fusion (fig. S17) confirmed that the nuclease domain–containing lobe is rearranged with respect to the α-helical lobe in this complex. In this rearrangement, the nuclease domain lobe closes over the putative nucleic acid binding cleft on the α-helical lobe, forming a central channel with a width of ~25 Å that spans the length of both lobes (fig. S16). Because nucleic acids cannot be visualized directly in EM structures of negatively stained complexes, this channel could be occupied by RNA and/or DNA.

We next wondered whether guide RNA alone induces the observed conformational rearrangements in SpyCas9, or whether both RNA and DNA are required for this structural change. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the architecture of SpyCas9:RNA in the absence of a bound target DNA molecule. Strikingly, reference-free 2D class averages of the SpyCas9:RNA showed a clear central channel similar to SpyCas9:RNA:DNA (fig. S19). Using the 3D reconstruction of SpyCas9:RNA:DNA low-pass filtered to 60 Å as a starting model, we obtained a reconstruction of SpyCas9:RNA at ~21-Å resolution (using the 0.5 FSC criterion), which reveals a conformation similar to that of the DNA-bound complex (CCC of 0.89 with DNA-bound versus 0.81 with apo), with a central channel extending between the two lobes (Fig. 5C and fig. S19). Both the SpyCas9:RNA and SpyCas9:RNA:DNA complexes were more resistant to limited proteolysis by trypsin than apo-SpyCas9 and displayed similar digestion patterns, in agreement with these nucleic acid–bound complexes occupying a similar structural state (fig. S20). Although the smaller lobe appears to undergo an additional ~50° rotation along an axis perpendicular to the channel in the DNA-bound complex compared to SpyCas9:RNA, the same ~100° rotation around the channel is observed in both structures. Thus, loading of crRNA and tracrRNA alone is sufficient to convert the endonuclease into an active conformation for target surveillance.

The Central Channel in SpyCas9 Accommodates Bound Target DNA and Guide RNAs

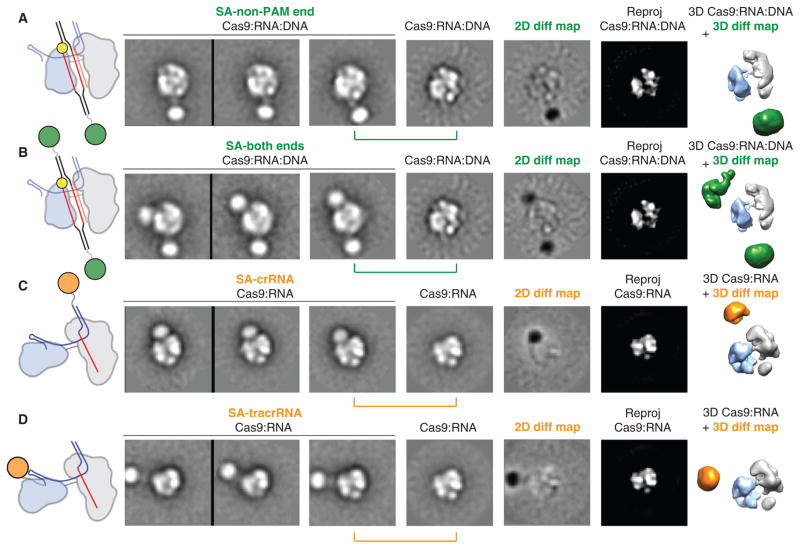

On the basis of the dimensions of the channel and the requirement for SpyCas9:RNA to recognize ~23 bp of its DNA substrate, we hypothesized that target DNA spans the central channel. To test this, we reconstituted SpyCas9:RNA:DNA complexes using DNA substrates containing 3′-biotin modifications (table S2) to visualize the duplex ends via streptavidin labeling. Negative-stain EM analysis of samples labeled at either the PAM-distal (non-PAM) end or both ends showed additional circular density below, or both above and below the complex, respectively, along the central channel positioned between the two structural lobes (Fig. 6, A and B). These data support the conclusion that the major lobes of SpyCas9 enclose the target DNA, positioning the RNA-DNA heteroduplex along the central channel with the PAM oriented near the top. The additional streptavidin densities in the double-end labeled class averages are not completely parallel with the channel and instead wrap around the nuclease lobe (Fig. 6B), consistent with some degree of bending of the target DNA. Finally, we determined the orientation of RNA within SpyCas9:RNA complexes using streptavidin labeling of crRNA and tracrRNA containing biotin at their 3′ termini, after ensuring that SpyCas9 retains full activity with these modified RNAs (fig. S21). Using the same 2D and 3D difference mapping approach, we pinpointed the 3′ end of the crRNA to the top of the channel (Fig. 6C), whereas the 3′ end of the tracrRNA is extended roughly perpendicular to the central channel from the side of the nuclease domain lobe (Fig. 6D). The finding that the 3′ end of the crRNA localizes to a similar position above the channel as the PAM-proximal side of the target suggests that the crRNA-DNA heteroduplex may be oriented roughly in parallel with the crRNA:tracrRNA duplex.

Fig. 6. Bound target DNA and guide RNAs span the central channel.

(A and B) Biotinylated DNA duplexes were labeled with streptavidin (SA) at either the end distal to the PAM (A, non-PAM) or both ends (B). From left to right: schematic of structures and labels, three representative reference-free 2D class averages, the corresponding reference-free 2D class average of unlabeled SpyCas9:RNA:DNA, a 2D difference map between the unlabeled and labeled structures, and the corresponding reprojection of the SpyCas9:RNA:DNA structure. The SpyCas9:RNA:DNA reconstruction is shown on the right with superimposed 3D difference density at ≥5σ (green) between the SpyCas9:RNA:DNA reconstruction and the SA-labeled reconstruction. (C and D) Single-particle EM analyses of SpyCas9:RNA labeled with SA at the 3′ end of the crRNA (C) or tracrRNA (D). Data are shown as in (A), with the 3D difference density at ≥6σ depicted in orange. The width of the boxes is ~316 Å.

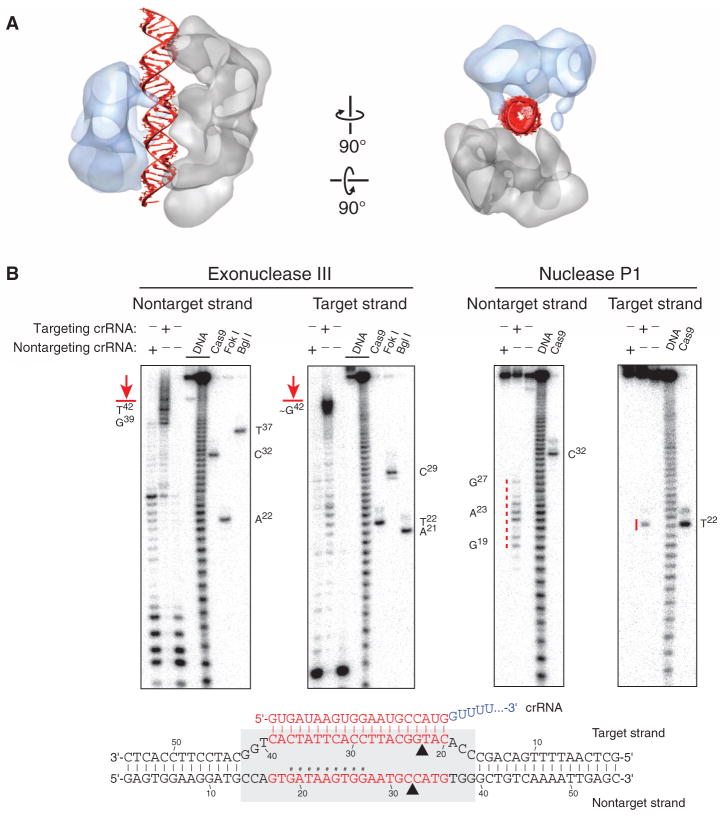

The channel between the lobes of SpyCas9: RNA:DNA can easily accommodate ~25 bp of a modeled A-form helix (Fig. 7A). Corroborating this, exonuclease III footprinting experiments indicated that Cas9 protects a ~26-bp segment of the target DNA (Fig. 7B). Additionally, P1 nuclease mapping experiments reveal that the displaced nontarget strand is susceptible to hydrolysis toward the 5′ end of the protospacer, whereas the target strand that hybridizes to crRNA is protected along nearly its entire length. These results are consistent with the formation of an R-loop structure (Fig. 7B), as observed for other CRISPR-Cas targeting complexes (36).

Fig. 7. SpyCas9 wraps around target DNA.

(A) The central channel of the SpyCas9:RNA:DNA reconstruction (transparent surface) can easily accommodate ~25 bp of an A-form duplex (red). (B) Footprinting experiment with target DNA bound by SpyCas9:RNA. A 55-bp DNA substrate was 5′-radiolabeled on either the target or the nontarget strand and incubated with catalytically inactive SpyCas9:RNA programmed with a complementary crRNA (targeting) or a mismatched control crRNA (nontargeting), before being subjected to exonuclease III (left) or nuclease P1 (right) treatment. Reaction products were resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; markers generated via digestion with Bgl I and Fok I restriction enzymes and wild-type SpyCas9:RNA are labeled. The borders of the DNA target protected by SpyCas9:RNA are indicated in red next to the gel and with a gray box (bottom), and nucleotides susceptible to P1 digestion are indicated in red next to the gel and with hashtags in the schematic at the bottom.

Discussion

The crystal structures of type II-A and II-C Cas9 proteins described here highlight the features in Cas9 enzymes that support their function as RNA-guided endonucleases. Cas9 enzymes adopt a bilobed architecture composed of a nuclease lobe containing juxtaposed RuvC and HNH nuclease domains and a variable α-helical lobe likely to be involved in nucleic acid binding. The identification of variable regions appended to a conserved Cas9 structural core provides a rationale for the diversity of crRNA:tracrRNA guide structures recognized by Cas9 enzymes and outlines a framework for protein engineering approaches aimed at altering catalytic function, guide RNA specificity, or PAM requirements.

Cross-linking experiments conducted in this study suggest that two unstructured tryptophan-containing loops in SpyCas9 contact the PAM in the target-bound complex. The location of the PAM binding loops suggests that Cas9 interrogates DNA using flexible regions that may form an ordered binding site upon engaging target DNA. It is tempting to speculate that the two tryptophan residues in SpyCas9 mediate base-stacking interactions with the GG dinucleotide PAM. Alternatively, the tryptophan residues could be involved in extrahelical base extrusion of the PAM motif, in a manner similar to the mechanisms of numerous DNA modification and repair enzymes (37–40). It is also possible that the tryptophan residues are not directly involved in PAM binding, but instead reside near the PAM binding pocket in the enzyme. We note, however, that the involvement of aromatic loop regions in SpyCas9 is highly reminiscent of the mechanism used by the Cascade complex in type I CRISPR-Cas systems (41). The lack of conservation of the PAM binding region in type II-C Cas9 enzymes is consistent with different PAM specificities observed for these endonucleases and points to distinct mechanisms of PAM recognition across the Cas9 enzyme family.

Single-molecule and biochemical experiments underscore the singular importance of PAM binding in both DNA interrogation and cleavage by Cas9 (42). The observed prevalence of PAM mutation as a mechanism of viral escape from CRISPR/Cas9 targeting (43, 44) has presumably spurred the evolution of Cas9 proteins with a variety of PAM specificities. It will be interesting to elucidate how PAM binding couples to Cas9 activation across the Cas9 superfamily, which has important implications for the use of these enzymes in genome engineering applications.

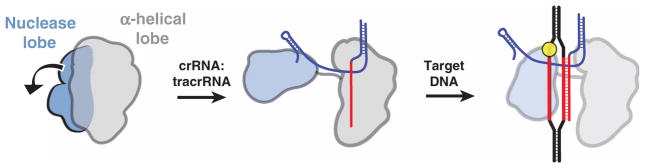

Both SpyCas9 and AnaCas9 structures support the conclusion that Cas9 enzymes maintain an autoinhibited conformation in the absence of nucleic acid ligands that requires restructuring upon guide RNA and target DNA binding. Consistent with this finding, EM reconstructions of SpyCas9–nucleic acid complexes show that the two lobes of the protein reorient substantially upon guide RNA association. On the basis of these observations, we propose a model for Cas9 function in which RNA loading drives structural rearrangements of the enzyme to enable productive encounters with target DNA (Fig. 8). Binding of crRNA:tracrRNA to Cas9 causes a substantial rotation of the small nuclease lobe relative to the larger lobe. This RNA-induced conformational change could occur either through direct interactions between the RNA and both lobes, or indirectly through allosteric effects. This reorganization may position the two major catalytic centers of the enzyme on opposite sides of the central channel, where the two separated strands are threaded into either active site.

Fig. 8. Model for RNA-induced conversion of Cas9 into a structurally activated DNA surveillance complex.

Upon binding the crRNA:tracrRNA guide, the two structural lobes of Cas9 reorient such that the two nucleic acid binding clefts face each other. This generates a central DNA binding channel, which allows access to dsDNA. Target DNA binding in the central channel and PAM-dependent R-loop formation result in a further structural rearrangement. Here, the nuclease domain lobe undergoes further rotation relative to the α-helical lobe, fully enclosing the DNA target, and the two nuclease domains engage both DNA strands for cleavage.

Although types I and III CRISPR-Cas RNA-guided surveillance complexes form helical architectures that wrap around the crRNA (45–48), Cas9 instead forms a central channel. The helical morphology in these other systems may have evolved to accommodate the topological requirements of a longer crRNA-DNA heteroduplex, and the open helical arrangement exhibited by the type I multisubunit Cascade complex likely facilitates recruitment of the trans-acting Cas3 nuclease for target cleavage (49). In contrast, Cas9 functions alone to both bind and cleave the DNA target, which could be facilitated by sequestering the substrate within the interior surface of the channel formed by both lobes. Although we do not observe extensive connecting density between the two lobes, we hypothesize that only one face will enable dsDNA to enter the central channel during 3D target search. Although further experiments will be necessary to elucidate the precise search and recognition mechanisms used by Cas9, our structural analysis shows that RNA loading serves as a key conformational switch in the activation and regulation of Cas9 enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Full details of experimental procedures are provided in the supplementary materials. SpyCas9 and its point mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 strain and purified essentially as described (8). SpyCas9 crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method from 0.1 M tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 0.2 to 0.3 M Li2SO4, and 14 to 15% (w/v) PEG 3350 (polyethylene glycol, molecular weight 3350) at 20°C. Diffraction data were measured at beamlines 8.2.1 and 8.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), and at beamlines PXI and PXIII of the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institut) and processed using XDS (50). Phasing was performed with crystals of selenomethionine (SeMet)–substituted SpyCas9 and native Cas9 crystals soaked individually with 10 mM Na2WO4, 10 mM CoCl2, 1 mM thimerosal, and 1 mM Er(III) acetate. Phases were calculated using autoSHARP (51) and improved by density modification using Resolve (52). The atomic model was built in Coot (53) and refined using phenix.refine (54).

A. naeslundii Cas9 (AnaCas9) was expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) as a fusion protein containing an N-terminal His10 tag followed by MBP and a TEV (tobacco etch virus) protease cleavage site. The protein was purified by Ni-NTA (nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid) and heparin affinity chromatography, followed by a gel filtration step. Crystals of native and SeMet-substituted AnaCas9 were grown from 10% (w/v) PEG 8000, 0.25 M calcium acetate, 50 mM magnesium acetate, and 5 mM spermidine. Native and SeMet single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) data sets were collected at beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source, processed using Mosflm (55), and scaled in Scala (56). Phases were calculated in Solve/Resolve (52), and the atomic model was built in Coot and refined in Refmac (57) and phenix.refine (54).

For biochemical assays, crRNAs were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, and tracrRNA was prepared by in vitro transcription as described (8). The sequences of RNA and DNA reagents used in this study are listed in table S2. Cleavage reactions were performed at room temperature in reaction buffer [20 mM tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol] using 1 nM radio-labeled dsDNA substrates and 1 nM or 10 nM Cas9:crRNA:tracrRNA. Cleavage products were resolved by 10% denaturing (7 M urea) PAGE and visualized by phosphorimaging. Cross-linked peptide-DNA heteroconjugates were obtained by incubating 200 pmol of catalytically inactive (D10A/H840A) Cas9 with crRNA:tracrRNA guide and 10-fold molar excess of BrdU containing dsDNA substrate for 30 min at room temperature, followed by irradiation with UV light (308 nm) for 30 min. S1 nuclease and phosphatase–treated tryptic digests were analyzed using a Dionex UltiMate3000 RSLCnano liquid chromatograph connected in-line with an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For negative-stain EM, apo-SpyCas9, SpyCas9: RNA, and SpyCas9:RNA:DNA complexes were reconstituted in reaction buffer, diluted to a concentration of ~25 to 60 nM, applied to glow-discharged 400-mesh continuous carbon grids, and stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate solution. Data were acquired using a Tecnai F20 Twin transmission electron microscope operated at 120 keV at a nominal magnification of either ×80,000 (1.45 Å at the specimen level) or ×100,000 (1.08 Å at the specimen level) using low-dose exposures (~20 e− Å−2) with a randomly set defocus ranging from −0.5 to −1.3 μm. A total of 300 to 400 images of each Cas9 sample were automatically recorded on a Gatan 4k × 4k CCD (charge-coupled device) camera using the MSI-Raster application within the automated macromolecular microscopy software Leginon (58). Particles were preprocessed in Appion (45) before projection matching refinement with libraries from EMAN2 and SPARX (59, 60) using RCT reconstructions (34) as initial models.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Tomizaki and V. Olieric (beamlines PXI and PXIII of the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut), and to G. Meigs, J. Holton, and C. Ralston (beamlines 8.2.2 and 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). We thank P. Kranzusch, S. Floor, R. Wilson, J. Noeske, Z. Kasahara, A. May, R. Haurwitz, P. Grob, Y. He, T. Houweling, D. Black, H.-W. Wang, J. Cate, and J. Berger for technical support and/or helpful discussions. This work was funded by HHMI (E.N. and J.A.D.), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation ( J.A.D.), and the National Science Foundation ( J.A.D.) and by start-up funds from the University of Zurich and the European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant ANTIVIRNA (M.J.). F.J. acknowledges support for study abroad from the China Scholarship Council. E.K. was funded by the German Academic Exchange Program (DAAD). S.H.S. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation and National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Research Fellowship programs. E.C. and J.A.D. acknowledge support from the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Education. E.N. and J.A.D. are HHMI Investigators. The atomic coordinates have been deposited into the PDB with accession codes 4CMP (SpyCas9), 4CMQ (Mn2+-bound SpyCas9), 4OGE (AnaCas9), and 4OGC (Mn2+-bound AnaCas9), respectively. The EM structures of apo-SpyCas9, SpyCas9:RNA, and SpyCas9:RNA:DNA have been deposited into the EMDataBank with accession codes EMD-5858, EMD-5859, and EMD-5860, respectively.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Attar S, Westra ER, van der Oost J, Brouns SJJ. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs): The hallmark of an ingenious antiviral defense mechanism in prokaryotes. Biol Chem. 2011;392:277–289. doi: 10.1515/bc.2011.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terns MP, Terns RM. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorek R, Lawrence CM, Wiedenheft B. CRISPR-mediated adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072911-172315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrangou R, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouns SJJ, et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makarova KS, et al. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jinek M, et al. A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karvelis T, et al. crRNA and tracrRNA guide Cas9-mediated DNA interference in Streptococcus thermophilus. RNA Biol. 2013;10:841–851. doi: 10.4161/rna.24203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9–crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2579–E2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson TR, Saroj SD, Llewellyn AC, Tzeng YL, Weiss DS. A CRISPR/Cas system mediates bacterial innate immune evasion and virulence. Nature. 2013;497:254–257. doi: 10.1038/nature12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makarova KS, Aravind L, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Unification of Cas protein families and a simple scenario for the origin and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Biol Direct. 2011;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chylinski K, Le Rhun A, Charpentier E. The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems. RNA Biol. 2013;10:726–737. doi: 10.4161/rna.24321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods. 2013;10:957–963. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cong L, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jinek M, et al. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. ELife. 2013;2:e00471. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi LS, et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert LA, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mali P, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou Z, et al. Efficient genome engineering in human pluripotent stem cells using Cas9 from Neisseria meningitidis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15644–15649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313587110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esvelt KM, et al. Orthogonal Cas9 proteins for RNA-guided gene regulation and editing. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger JM, Gamblin SJ, Harrison SC, Wang JC. Structure and mechanism of DNA topoisomerase II. Nature. 1996;379:225–232. doi: 10.1038/379225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapranauskas R, et al. The Streptococcus thermophilus CRISPR/Cas system provides immunity in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9275–9282. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garneau JE, et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010;468:67–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, et al. Processing-independent CRISPR RNAs limit natural transformation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Cell. 2013;50:488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonfara I, et al. Phylogeny of Cas9 determines functional exchangeability of dual-RNA and Cas9 among orthologous type II CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Górecka KM, Komorowska W, Nowotny M. Crystal structure of RuvC resolvase in complex with Holliday junction substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9945–9955. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W. An equivalent metal ion in one- and two-metal-ion catalysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1228–1231. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang W. Nucleases: Diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q Rev Biophys. 2011;44:1–93. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: Two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivančić-Baće I, Howard JA, Bolt EL. Tuning in to interference: R-loops and Cascade complexes in CRISPR immunity. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen BW, Landthaler M, Shub DA, Stoddard BL. DNA binding and cleavage by the HNH homing endonuclease I-HmuI. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radermacher M, Wagenknecht T, Verschoor A, Frank J. Three-dimensional reconstruction from a single-exposure, random conical tilt series applied to the 50S ribosomal subunit of Escherichia coli. J Microsc. 1987;146:113–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chacón P, Wriggers W. Multi-resolution contour-based fitting of macromolecular structures. J Mol Biol. 2002;317:375–384. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jore MM, et al. Structural basis for CRISPR RNA-guided DNA recognition by Cascade. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:529–536. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang CG, et al. Crystal structures of DNA/RNA repair enzymes AlkB and ABH2 bound to dsDNA. Nature. 2008;452:961–965. doi: 10.1038/nature06889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi Y, et al. Encounter and extrusion of an intrahelical lesion by a DNA repair enzyme. Nature. 2009;462:762–766. doi: 10.1038/nature08561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crenshaw CM, et al. Enforced presentation of an extrahelical guanine to the lesion recognition pocket of human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase, hOGG1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24916–24928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song J, Rechkoblit O, Bestor TH, Patel DJ. Structure of DNMT1-DNA complex reveals a role for autoinhibition in maintenance DNA methylation. Science. 2011;331:1036–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1195380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sashital DG, Wiedenheft B, Doudna JA. Mechanism of foreign DNA selection in a bacterial adaptive immune system. Mol Cell. 2012;46:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semenova E, Nagornykh M, Pyatnitskiy M, Artamonova II, Severinov K. Analysis of CRISPR system function in plant pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;296:110–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semenova E, et al. Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10098–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiedenheft B, et al. Structures of the RNA-guided surveillance complex from a bacterial immune system. Nature. 2011;477:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staals RHJ, et al. Structure and activity of the RNA-targeting Type III-B CRISPR-Cas complex of Thermus thermophilus. Mol Cell. 2013;52:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rouillon C, et al. Structure of the CRISPR interference complex CSM reveals key similarities with Cascade. Mol Cell. 2013;52:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spilman M, et al. Structure of an RNA silencing complex of the CRISPR-Cas immune system. Mol Cell. 2013;52:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sinkunas T, et al. In vitro reconstitution of Cascade-mediated CRISPR immunity in Streptococcus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2013;32:385–394. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terwilliger T. SOLVE and RESOLVE: Automated structure solution, density modification and model building. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11:49–52. doi: 10.1107/S0909049503023938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Powell HR, Johnson O, Leslie AGW. Autoindexing diffraction images with iMosflm. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1195–1203. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912048524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: The new Leginon system. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hohn M, et al. SPARX, a new environment for Cryo-EM image processing. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang G, et al. EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ashkenazy H, Erez E, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2010: Calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server):W529–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials