Involvement of Notch signaling in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (original) (raw)

Abstract

During development of the nervous system, the fate of stem cells is regulated by a cell surface receptor called Notch. Notch is also present in the adult mammalian brain; however, because Notch null mice die during embryonic development, it has proven difficult to determine the functions of Notch. Here, we used Notch antisense transgenic mice that develop and reproduce normally, but exhibit reduced levels of Notch, to demonstrate a role for Notch signaling in synaptic plasticity. Mice with reduced Notch levels exhibit impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) at hippocampal CA1 synapses. A Notch ligand enhances LTP in normal mice and corrects the defect in LTP in Notch antisense transgenic mice. Levels of basal and stimulation-induced NF-κB activity were significantly decreased in mice with reduced Notch levels. These findings suggest an important role for Notch signaling in a form of synaptic plasticity known to be associated with learning and memory processes.

Keywords: long-term potentiation, long-term depression, Alzheimer's disease, NF-κB, learning and memory

Notch (Notch 1) belongs to a conserved family of transmembrane receptors involved in cell–cell interactions that allow neighboring cells to adopt different fates during development (1). Notch is a 300-kDa heterodimeric single-span transmembrane protein consisting of a 180-kDa extracellular domain and a 115-kDa transmembrane domain. Binding of one of the two ligands, Delta or Jagged, to Notch leads to proteolytic cleavages of Notch, first in an extracellular domain and then in a transmembrane domain. The latter cleavage releases the Notch intracellular domain that translocates to the nucleus where it binds to and activates transcription factors (2, 3). Studies of Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, and mice have demonstrated an essential role for Notch signaling in maintaining neural stem cells in a proliferative state (1). Notch is expressed by neurons in the adult mouse brain where it is present at particularly high levels in the hippocampus (4). Although a critical role for Notch signaling in development of the nervous system has been established, the function of this signaling pathway in the mature nervous system has not been established. It was reported that Notch signaling inhibits neurite outgrowth in postmitotic neurons (5). Some of the same signaling mechanisms that regulate neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth during development, including glutamate (6), cell adhesion molecules (7), and neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (8) can also regulate the formation and plasticity of synapses. We wondered if this possibility might also be the case with Notch.

The prospect that Notch plays a role in learning and memory is suggested by a link between Notch signaling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Mutations in the genes encoding the amyloid precursor protein and presenilins 1 and 2 are responsible for some cases of early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease (9). The phenotype of presenilin 1-null mice is identical to that of Notch null mice (10), suggesting closely related functions of these two proteins. More recent studies (11) have shown that presenilin 1 is an essential component of an enzyme activity called γ-secretase that cleaves and activates Notch. Whereas forebrain-specific deletion of presenilin 1 in mice results in learning and memory impairment (12), presenilin 1 heterozygous knockout mice exhibit deficits in hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) (13), and transgenic mice carrying presenilin 1 mutations that cause Alzheimer's disease show impaired synaptic function and memory (14, 15).

Although Notch has been localized to synaptic membranes, its contribution to synaptic function is far less clear (16). Notch may function as an adhesion molecule in developing neurons and plays an important role in promoting neurite outgrowth (17). In differentiated neurons, Notch signaling has been shown to inhibit neurite growth (5) and to promote dendritic branching (16). The latter study suggests that Notch may play a role in shaping the structure of the dendritic arbors, which is a critical determinant of the processing of synaptic inputs. In the present study, we report a role for Notch signaling in the induction of LTP and provide evidence that Notch directly affects the molecular changes required for plasticity-related changes in synapses.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Evaluation of Notch Expression. Notch antisense (NAS) transgenic mice were generated by using a Notch antisense construct expressed under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus long-terminal repeat promoter (18). To determine levels of Notch protein, homogenates were prepared from snap-frozen hippocampal tissues of control and NAS mice, and total proteins were separated by SDS/7.5% PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred from the gel to a nitrocellulose filter (Bio-Rad). Membranes were incubated in blocking solution (5% milk in Tween Tris-buffered saline) overnight at 4°C followed by 1 h incubation with a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against Notch (a generous gift from A. Israel, Institut Pasteur, Paris; ref. 19). Membranes were then incubated for 1 h with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and bands were visualized by using a chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL, Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assay and Notch Activity Assay. Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay analysis of NF-κB DNA-binding proteins was performed by using methods similar to those described (20). Cell extracts containing DNA-binding proteins were prepared from hippocampal slices at 2 h after tetanic stimuli or without stimuli, and gel-shift assays performed by using a commercially available assay kit (Promega). Notch activity was assayed by using the method described (5, 21). The transactivation of 4xwtCBF1-luciferase reporter construct in the transfected hippocampal tissues was measured as an indicator of endogenous Notch activity.

Hippocampal Slice Preparations and Electrophysiology Methods. Hippocampal slices from young adult male mice were cut at 350 μm and were maintained as described (22). Slices were allowed to recover for at least 1 h before recording. Organotypic hippocampal slice cultures were prepared from 3- to 5-day-old mice as described (23). Recordings were made from slices that had been maintained in culture for 6–10 days. Slices were transferred to a submerged recording chamber, and were perfused continuously at 2 ml/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid at 30–32°C. The artificial cerebrospinal fluid contained 120 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose. All solutions for LTP and long-term depression (LTD) studies contained 25 μM picrotoxin to block γ-aminobutyric acid type A-mediated activity. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in CA1 stratum radiatum. The stimuli (30 μs duration at a frequency of 0.033 Hz) were delivered through fine bipolar tungsten electrodes to activate Schaffer collateral/commissural afferents (24). LTP- and LTD-inducing stimuli consisted of one train of 100 stimuli at 100 Hz, and 900 stimuli at 1 Hz, respectively. Data were collected and analyzed on or off-line by using pclamp 8 software.

Results

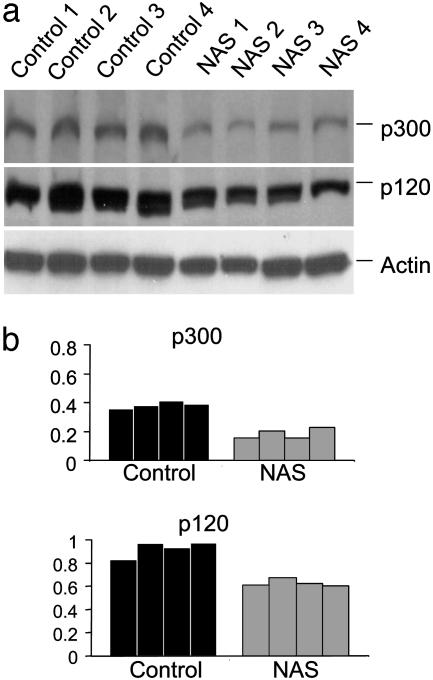

Notch Levels Are Decreased in Hippocampal Cells in NAS Transgenic Mice. A previous study (18) showed that levels of Notch mRNA and protein are decreased by ≈50–70% in hematopoietic cells from the same line of NAS transgenic mice used in the present study. To determine whether Notch expression was also decreased in brain cells of the NAS mice, we performed immunoblot analyses of proteins in homogenates of hippocampus of control and NAS mice. Blots were probed by using a polyclonal antibody generated against the Notch intracellular domain. Bands for full-length (p300) and a cleaved form of the Notch protein (p120) in samples from NAS mice were weaker than those in samples from control mice (Fig. 1_a_). Densitometric analysis revealed a significant 40–50% decrease in Notch protein level in the hippocampus of NAS mice (Fig. 1_b_). RT-PCR analysis revealed that Notch mRNA level in samples from hippocampus and cerebral cortex was reduced by≈50% in the NAS mice (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Levels of Notch protein are decreased in NAS mice. (a) Immunoblots showing full-length Notch (p300) and a cleared form of the protein (p120) in homogenates prepared from hippocampal tissues of four control and four NAS mice. Blots were reprobed with an anti-actin antibody. (b) Densitometric analysis showing the relative levels of the indicated proteins in control and NAS mice (normalized to the level of actin).

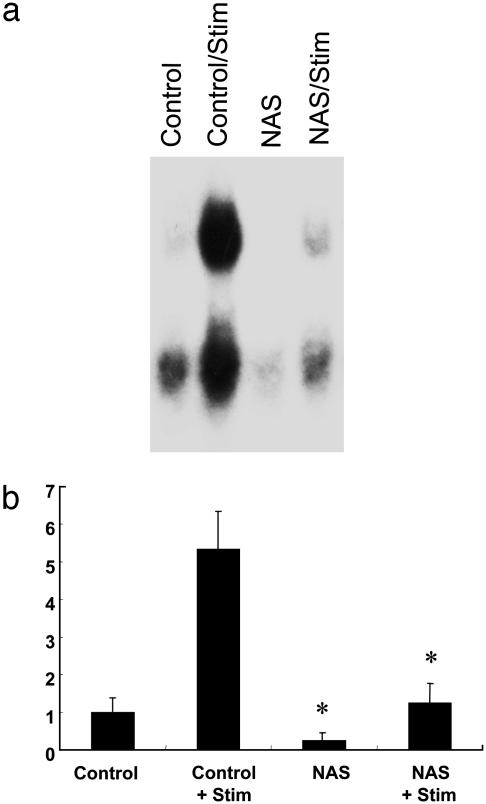

Constitutive and Activity-Induced NF-κB DNA-Binding Activity Is Decreased in Hippocampi from Notch Antisense Mice. Previous studies (25, 26) have provided evidence that the transcription factor NF-κB plays a role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Recent findings in studies of hematopoietic cells have shown that Notch can regulate NF-κB activity (18). We therefore used an EMSA to assess NF-κB activity in hippocampal slices from control and NAS mice under basal conditions and after high-frequency stimulation (HFS; 100 Hz for 1 s). The constitutive level of NF-κB DNA-binding activity was significantly lower in slices from NAS mice compared with slices from control mice (Fig. 2). HFS induced a large 5-fold increase in NF-κB activity in slices from control mice. Although HFS also increased NF-κB activity in slices from NAS mice, the magnitude of the increase was significantly less than in slices from control mice (Fig. 2). These results indicate that Notch signaling enhances both constitutive and activity-induced NF-κB activity in the hippocampus.

Fig. 2.

Activation of the transcription factor NFκB is decreased in NAS mice. (a) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing shifted NF-κB proteins in homogenates of hippocampal slices from control or NAS mice that either were not or were subjected to HFS; hippocampi were homogenized 2 h after stimulation. (b) Results of densitometric analysis of electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Values are the mean and SEM (n = 6). *, P < 0.01 compared with corresponding value for slices from control mice.

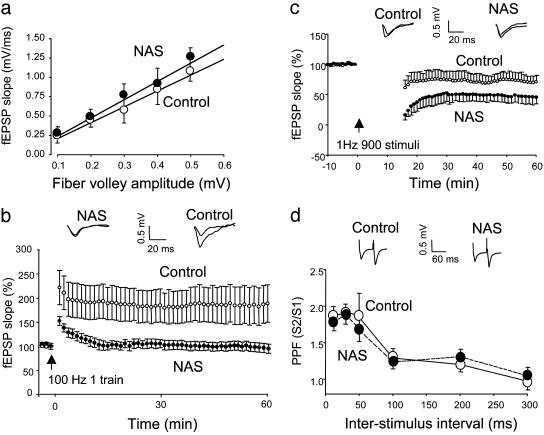

LTP Is Impaired and LTD Is Enhanced in Notch-Antisense Transgenic Mice. We investigated the involvement of Notch signaling in synaptic plasticity by performing electrophysiological analyses of synaptic transmission at CA1 synapses in hippocampal slices from control and NAS mice. Input - output curves were essentially identical in hippocampal slices from control and NAS mice (Fig. 3_a_) indicating that reduced levels of Notch did not affect basal synaptic transmission (seven slices from six different mice). HFS (100 Hz, 1 s) significantly augmented fEPSPs in slices from control mice with LTP lasting for at least 60 min after HFS (Fig. 3_b_). The normalized fEPSP after HFS in slices from control mice was 191 ± 15.3% of the value before HFS (10 slices from seven different mice). On the other hand, the fEPSP was only transiently augmented after HFS in slices from NAS mice with the magnitude of fEPSP slope after HFS in NAS mice being significantly smaller than that of control mice; indeed, no LTP was evident 60 min after HFS in slices from NAS mice (98.2 ± 5.2% of the basal value). These results indicate that the ability to induce posttetanic potentiation still remains in slices from NAS mice, but the maintenance of LTP is completely abolished in these transgenic mice.

Fig. 3.

LTP is impaired and LTD is enhanced in NAS mice. (a) fEPSP slopes were plotted against stimulus intensities as input and output relationships for control and NAS transgenic mice. The input–output curves for control and NAS were not significantly different from each other, indicating that a reduction in Notch levels does not affect basal synaptic transmission. (b) The time courses of normalized initial slope measurements of fEPSP evoked by HFS in hippocampal CA1 neurons in slices from control and NAS mice. Each data point represents the averaged data for 1 min (three consecutive sweeps with an interval of 20 sec). Values are the mean ± SEM of recordings made from slices from seven different mice (one to three slices analyzed per mouse). LTP was significantly impaired in NAS mice (P < 0.01). (c) The time courses of normalized initial slope measurements of fEPSP after LFS in hippocampal CA1 neurons in slices from control and NAS mice. Values are the mean ± SEM of recordings made from slices from six different mice (one to three slices analyzed per mouse). LTD was significantly enhanced in NAS mice (P < 0.01). (d) PPF is normal in NAS mice. PPF curves were generated at interpulse intervals of 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 300 ms in slices from control and NAS mice.

Whereas HFS can induce LTP, low-frequency stimulation (LFS) of axonal inputs to CA1 neurons induces LTD. We determined whether Notch modulates LTD by recording the fEPSP before and after LFS (1 Hz for 15 min). Slices from control mice showed a significant and progressive reduction in fEPSP slope during a 60-min period after LFS (Fig. 3_c_). In contrast, the fEPSP slope decreased by a greater amount after LFS in slices from NAS mice during the first 30 min and then returned to a level that is closer to that of slices from control mice by 60 min after LFS. These results indicate that the initiation of LTD is strongly enhanced, whereas the maintenance of LTD is moderately augmented in NAS mice.

To gain insight into the mechanism whereby Notch might affect synaptic plasticity, we evaluated paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), a measure of the amount of neurotransmitter released from presynaptic terminals. Values for the fEPSP slope induced by the second stimulation divided by the first stimulation were plotted against each interstimulus interval. The PPF curves were essentially identical in slices from control and NAS mice (Fig. 3_d_), indicating that Notch most likely modulates LTP postsynaptically with little or no effect on presynaptic function.

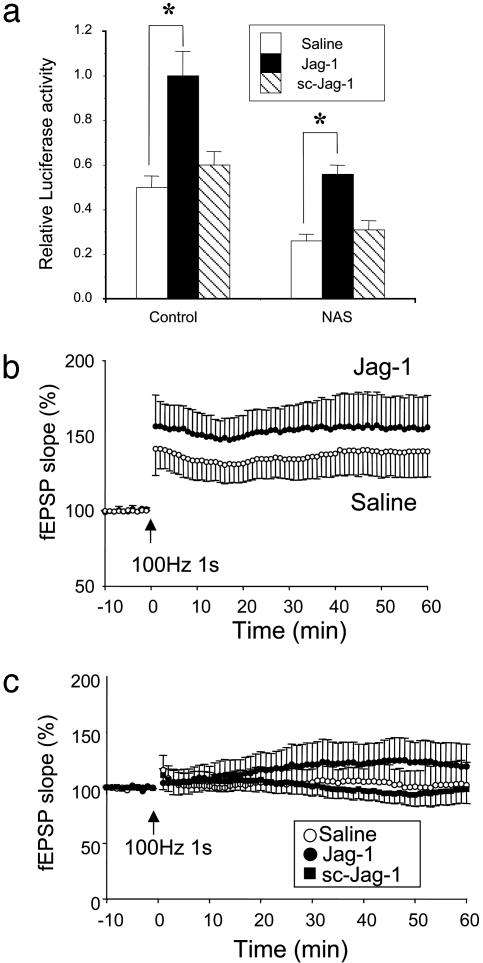

The Notch Ligand Jagged Enhances Notch Activity and LTP. Notch is a membrane-spanning receptor protein that is bound and activated by several Notch ligands including Jagged, a ligand expressed in the hippocampus (27). We further explored the role of Notch in synaptic plasticity by incubating organotypic hippocampal slices in the presence of a peptide corresponding to the Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 domain of human Jagged-1 (Jag-1). This peptide has previously been shown to bind and activate Notch (28). First, we measured endogenous Notch activity by using a 4xwtCBF1-luciferase reporter construct in hippocampal tissues before and after the treatment with the Jag-1 peptide or its control peptide with a scrambled amino acid sequence (sc-Jag-1). The constitutive activity of Notch was significantly lower in tissues from NAS mice compared with tissues from control mice, and Notch activity was dramatically increased by treatment with the Jag-1 peptide in control and NAS mice (Fig. 4_a_). The magnitude of LTP was significantly increased in slices from control mice that had been incubated with Jag-1 compared with slices incubated with saline or sc-Jag-1 (Fig. 4_b_). Moreover, when slices from NAS mice were incubated in the presence of Jag-1, LTP was significantly enhanced compared with slices from NAS mice that had been treated with sc-Jag-1 or no peptide (Fig. 4_c_). These findings suggest that activation of Notch is sufficient to enhance LTP at CA1 hippocampal synapses.

Fig. 4.

The Notch ligand Jagged enhances Notch activity and LTP in hippocampal slices from control mice and restores them in slices from NAS mice. (a) The graph shows the mean values of relative luciferase activity from control and NAS hippocampal tissues. The Jag-1 peptide (1 μM) significantly increased Notch activity in both control and NAS mice (*, P < 0.05, n = 5–6), whereas sc-Jag-1 showed no effect. (b) LTP was examined after 48 h of incubation of slices with Jag-1 (1 μM) in organotypic hippocampal slices from control mice. LTP was significantly facilitated in Jag-1-treated slices compared with the untreated group (P < 0.05). (c) LTP was analyzed after 48 h of incubation with 1 μM Jag-1 or 1 μM sc-Jag-1 in NAS mice. The potentiation of the fEPSP after titanic stimulation was significantly greater in slices treated with Jag-1 compared with slices treated with either saline (P < 0.05) or sc-Jag-1 (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our data provide direct evidence that Notch regulates synaptic plasticity at CA1 synapses in the hippocampus. Analyses of synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices from transgenic mice with reduced levels of Notch, and in slices exposed to a peptide agonist of Notch, suggest that Notch signaling enhances LTP, a process in which synapses are strengthened as the result of HFS. The enhancement of LTP by Notch appears to result primarily from postsynaptic changes, because PPF, an indicator of neurotransmitter release from presynaptic terminals, was not changed in slices from mice with reduced Notch levels. Whereas the cellular sources and localization of Notch ligands such as Jag-1 have not been clearly established, the ability of exogenous Jag-1 peptide to enhance LTP suggests that Notch signaling is not fully activated under basal conditions. In addition to enhancing LTP, Notch signaling may modify LTD because we found that the induction of LTD was increased in slices from mice with reduced Notch levels. Collectively, the latter findings suggest that Notch signaling enhances LTP and reduces LTD. Data suggest that LTP is associated with, and possibly required for, learning and memory. Our findings therefore suggest an important role for Notch signaling in learning and memory, a possibility consistent with a recent study (29) that demonstrated impaired learning in Notch heterozygous knockout mice.

The mechanism(s) by which Notch signaling regulates synaptic plasticity remains to be determined. Studies of the developing nervous system have identified several gene targets of Notch that control differentiation of neurons and neurite outgrowth. Several transcription factors are induced by Notch signaling that appear to be important mediators of the effects of Notch signaling on neuronal differentiation, including members of the Hes and neurogenin families (30). However, the proteins affected by Notch signaling that actually mediate the effects of Notch on developmental plasticity are unknown. Recent studies (18, 28) have shown that Notch affects the activation of NF-κB in several types of cells and thereby regulates their differentiation. For example, activation of Notch with Jag-1 induces maturation of human keratinocytes through an NF-κB-mediated mechanism (28), and data suggest a role for NF-κB in the regulation of differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (18). Our data show that HFS increases NF-κB activity in the hippocampus and provide evidence that Notch signaling plays an important role in both constitutive and activity-dependent NF-κB activation. Emerging evidence suggests that NF-κB plays roles in several types of neural plasticity, including learning and memory. NF-κB is present in synapses, where it can be activated in response to electrical stimulation and glutamate (25). In addition, selective blockade of NF-κB activation by using decoy DNA-impaired LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses (26). Moreover, studies of mice deficient in the p50 subunit of NF-κB suggest an important role for NF-κB in learning and memory (31). Although the mechanism whereby NF-κB regulates synaptic plasticity is not known, this transcription factor has been shown to affect whole-cell currents through _N_-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channels and voltage-dependent calcium channels (20). NF-κB also induces genes that modify oxyradical metabolism and mitochondrial function (32), processes thought to modulate synaptic plasticity (33). Moreover, calcium signaling was recently linked to NF-κB activation in neurons by a mechanism involving calmodulin-dependent kinase II and Akt kinase, pathways previously linked to synaptic plasticity and learning and memory (34).

Previous studies have shown that actions of Notch are dose-dependent (35). Altering the steady-state level of Notch can have disproportionately large effects in various systems. For example, T cells from the same NAS mice employed in our study have impaired NF-κB activity and defective proliferation in response to T cell receptor stimulation (36). The same is true for thymocytes and for bone marrow hematopoietic precursors (18). Murine erythroleukemia cells expressing the same antisense construct used to develop these mice are completely unable to differentiate and are exquisitely sensitive to drug-induced apoptosis, even though reduction of Notch levels is in the same order of magnitude (37). These cells also have reduced NF-κB activity. Therefore, there is substantial evidence that (i) relatively modest decreases of Notch signaling can have considerable biological consequences; and (ii) constitutive levels of Notch activity are essential to maintain NF-κB activity in various cell types.

We found that the application of the Jag-1 peptide augments LTP in both control and NAS mice. We used a concentration of Jag-1 (1 μM) that was presumably able to augment the action of endogenous Notch ligands. Further studies will be required to establish how much agonist is needed to maintain and facilitate LTP and how much Notch activity is required for synaptic plasticity. In addition, it will be important to determine whether other Notch receptor agonists such as Delta and F3/Contactin regulate LTP and LTD. Although immunostaining and in situ hybridization data showing Notch expression in the brain were reported (38), the expression pattern of Notch receptors and Notch receptor ligands in the murine hippocampus is still unclear, and such knowledge will help clarify which receptors and ligands contribute to synaptic plasticity.

Beyond the suggestion that Notch signaling plays an important role in synaptic plasticity and learning and memory, the present findings suggest a mechanism whereby disease-related alterations in Notch signaling might contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. γ-secretase, the enzyme activity that cleaves the amyloid precursor protein to generate amyloid β-peptide, also mediates ligand-induced cleavage of Notch (11). Presenilin 1 is an essential component of γ-secretase activity and cleavage of Notch by this enzyme is critical for normal brain development. Presenilin 1 mutations that cause early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease impair generation of the Notch intracellular signaling domain (39) and also alter synaptic plasticity (14). Presenilin 1 mutations also perturb neuronal calcium homeostasis (40), which might affect Notch signaling and synaptic plasticity. Finally, our findings that Notch signaling regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity suggest that efforts to develop γ-secretase inhibitors as therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease, based on their ability to reduce generation of amyloid β-peptide from amyloid precursor protein may be hampered by the simultaneous inhibition of Notch cleavage (41).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. M. Thompson for advice on organotypic slice culture and for critical comments on the manuscript, and A. Israel for providing us with the polyclonal antibody raised against the Notch intracellular domain.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: LTP, long-term potentiation; LTD, long-term depression; NAS, Notch antisense; fEPSP, field excitatory postsynaptic potential; HFS, high-frequency stimulation; LFS, low-frequency stimulation; PPF, paired-pulse facilitation; Jag-1, Jagged-1; sc-Jag-1; Jag-1 with a scrambled amino acid sequence.

References

- 1.Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., Matsuno, K. & Fortini, M. E. (1995) Science 268**,** 225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroeter, E. H., Kisslinger, J. A. & Kopan, R. (1998) Nature 393**,** 382-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Struhl, G. & Adachi, A. (1998) Cell 93**,** 649-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berezovska, O., Xia, M. O. & Hyman B. T. (1998) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 57**,** 738-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sestan, N., Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. & Rakic, P. (1999) Science 286**,** 741-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattson, M. P., Dou, P. & Kater, S. B. (1988) J. Neurosci. 8**,** 2087-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gary, D. S., Milhavet, O., Camandola, S. & Mattson, M. P. (2003) J. Neurochem. 84**,** 878-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, A., Wang, S., Cai, J., Rao, M. S. & Mattson, M. P. (2003) Dev. Biol. 258**,** 319-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogaeva, E. (2002) Neuromolecular Med. 2**,** 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen, J., Bronson, R. T., Chen, D. F., Xia, W., Selkoe, D. J. & Tonegawa, S. (1997) Cell 89**,** 629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song, W., Nadeau, P., Yuan, M., Yang, X., Shen, J. & Yankner, B. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96**,** 6959-6963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, R., Rampon, C., Tang, Y. P., Shrom, D., Jin, J., Kyin, M., Sopher, B., Miller, M. W., Ware, C. B., Martin, G. M., et al. (2001) Neuron 32**,** 911-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morton, R. A., Kuenzi, F. M., Fitzjohn, S. M., Rosahl, T. W., Smith, D., Zheng, H., Shearman, M., Collingridge, G. L. & Seabrook, G.R. (2002) Neurosci. Lett. 319**,** 37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Begley, J. G., Duan, W., Chan, S., Duff, K. & Mattson, M. P. (1999) J. Neurochem. 72**,** 1030-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pak, K., Chan, S. L. & Mattson, M. P. (2003) Neuromolecular Med. 3**,** 53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redmond, L., Oh, S. R., Hicks, C., Weinmaster, G. & Ghosh, A. (2000) Nat. Neurosci. 3**,** 30-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin, J. L., Berechid, B. E., Cutting, F. B., Presente, A., Chambers, C. B., Foltz, D. R., Ferreira, A. & Nye, J. S. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9**,** 1448-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng, P., Zlobin, A., Volgina, V., Gottipati, S., Osborne, B., Simel, E. J., Miele, L. & Gabrilovich, D. I. (2001) J. Immunol. 167**,** 4458-4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta-Rossi, N., Le Bail, O., Gonen, H., Brou, C., Logeat, F., Six, E., Ciechanover, A. & Israel, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276**,** 34371-34378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furukawa, K. & Mattson, M. P. (1998) J. Neurochem. 70**,** 1876-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh, J. J., Henkel, T., Salmon, P., Robey, E., Peterson, M. G. & Hayward, S. D. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16**,** 952-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, Y., Wu, J., Rowan, M. J. & Anwyl, R. (1998) J. Physiol. (London) 513**,** 467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanc, E. M., Bruce-Keller, A. J. & Mattson, M. P. (1998) J. Neurochem. 70**,** 958-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlson, G., Wang, Y. & Alger, B. E. (2002) Nat. Neurosci. 5**,** 723-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meberg, P. J., Kinney, W. R., Valcourt, E. G. & Routtenberg, A. (1996) Brain Res. 38**,** 179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albensi, B. C. & Mattson M. P. (2000) Synapse 35**,** 151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stump, G., Durrer, A., Klein, A. L., Lutolf, S., Suter, U. & Taylor, V. (2002) Brain Mech. Dev. 114**,** 153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nickoloff, B. J., Qin, J. Z., Chaturvedi, V., Denning, M. F., Bonish, B. & Miele, L. (2002) Cell Death Differ. 9**,** 842-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa, R. M., Honjo, T. & Silva, A. J. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13**,** 1348-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyano-Nakagawa, N., Kim, J., Anderson, D. & Kintner, C. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127**,** 4203-4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kassed, C. A., Willing, A. E., Garbuzova-Davis, S., Sanberg, P. R. & Pennypacker, K. R. (2002) Exp. Neurol. 176**,** 277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson, M. P. & Camandola, S. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107**,** 247-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calabresi, P., Gubellini, P., Picconi, B., Centonze, D., Pisani, A., Bonsi, P., Greengard, P., Hipskind, R. A., Borrelli, E. & Bernardi, G. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21**,** 5110-5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisman, J., Schulman, H. & Cline, H. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3**,** 175-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heitzler, P. & Simpson, P. (1991) Cell 64**,** 1083-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palaga, T., Miele, L., Golde, T. E. & Osborne, B. A. (2003) J. Immunol. 171**,** 3019-3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang, M. S., Miao, H., Carlesso, N., Shelly, L., Zlobin, A., Darack, N., Qin, J. Z., Nickoloff, B. J. & Miele, L. (2004) J. Cell. Physiol. 199**,** 418-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka, M., Kadokawa, Y., Hamada, Y. & Marunouchi, T. (1999) J. Neurobiol. 41**,** 524-539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moehlmann, T., Winkler, E., Xia, X., Edbauer, D., Murrell, J., Capell, A., Kaether, C., Zheng, H., Ghetti, B., Haass, C., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99**,** 8025-8030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattson, M. P., Chan, S. L. & Camandola, S. (2001) BioEssays 23**,** 733-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis, H. D., Perez Revuelta, B. I., Nadin, A., Neduvelil, J. G., Harrison, T., Pollack, S. J. & Shearman, M. S. (2003) Biochemistry 42**,** 7580-7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]