Randomized Controlled Trial of Adalimumab in Patients With Nonpsoriatic Peripheral Spondyloarthritis (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with active nonpsoriatic peripheral spondyloarthritis (SpA).

Methods

ABILITY-2 is an ongoing phase III, multicenter study of adalimumab treatment. Eligible patients age ≥18 years fulfilled the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria for peripheral SpA, did not have a prior diagnosis of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), or ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and had an inadequate response or intolerance to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive adalimumab 40 mg every other week or matching placebo for 12 weeks, followed by a 144-week open-label period. The primary end point was the proportion of patients achieving 40% improvement in disease activity according to the Peripheral SpA Response Criteria (PSpARC40) at week 12. This was defined as ≥40% improvement from baseline (≥20-mm absolute improvement on a visual analog scale) in patient's global assessments of disease activity and pain, and ≥40% improvement in at least one of the following features: swollen joint and tender joint counts, total enthesitis count, or dactylitis count. Adverse events were recorded throughout the study.

Results

In total, 165 patients were randomized to a treatment group, of whom 81 were randomized to receive placebo and 84 to receive adalimumab. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar between the 2 groups. At week 12, a greater proportion of patients receiving adalimumab achieved a PSpARC40 response compared to patients receiving placebo (39% versus 20%; P = 0.006). Overall, improvement in other outcomes was greater in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group. The rates of adverse events were similar in both treatment groups.

Conclusion

Treatment with adalimumab ameliorated the signs and symptoms of disease and improved physical function in patients with active nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA who exhibited an inadequate response or intolerance to NSAIDs, with a safety profile consistent with that observed in patients with AS, PsA, or other immune-mediated diseases.

The spondyloarthritides (SpA) refer traditionally to a group of interrelated diseases, which includes ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), reactive arthritis (ReA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–related arthritis, and undifferentiated SpA (uSpA). The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) developed and validated updated classification criteria for SpA on the basis of the predominant clinical manifestation found in these various SpA disease subsets, classified as either axial SpA (1) or peripheral SpA (2).

The ASAS classification criteria for peripheral SpA (2) were meant to be applied to patients with an established diagnosis of SpA, peripheral arthritis (usually asymmetric or predominantly involving the lower limbs), enthesitis, and/or dactylitis. These criteria encompass patients who may have been diagnosed in the past as having PsA, IBD-related arthritis, ReA, or uSpA with predominantly peripheral manifestations. Other than those with PsA, such patients with peripheral SpA have not been well characterized or included in clinical trials of new therapies. There is only limited information on the epidemiology of nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA, with some data provided in studies of patients with IBD-related arthritis (3–5) or those with ReA (5,6). However, the majority of patients with peripheral SpA present with features typical of SpA, but their disease overall does not fit in any of these categories. These patients have been labeled as having uSpA and will probably benefit most from the new classification criteria for peripheral SpA. For example, the most cited study about a possible effect of sulfasalazine in patients with SpA included only patients with AS, PsA, or ReA (7). Epidemiologic data on this subset are also quite limited (5,8,9). With the availability of the ASAS peripheral SpA criteria, there is now an opportunity to classify nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA patients for study inclusion in a therapeutic clinical trial.

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy, including adalimumab, has been proven effective for the treatment of PsA (10–13). Patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA may also benefit from anti-TNF therapy. The efficacy of adalimumab in nonpsoriatic, non-AS peripheral SpA was demonstrated in a small study from The Netherlands (14); however, the disease in those patients was classified using the older European Spondylarthropathy Study Group criteria (15).

ABILITY-2 is the first multicenter, global, randomized controlled trial to be conducted in patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with active nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA who fulfilled the ASAS peripheral SpA criteria and who had an inadequate response to at least 2 nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or were intolerant to, or had a contraindication for, NSAIDs.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age and fulfilled the ASAS criteria for peripheral SpA (2), with onset of peripheral SpA symptoms at least 3 months prior to the study. Patients with a history of psoriasis or PsA or with a diagnosis of AS defined by the modified New York criteria (16) were excluded. Eligible patients must have active disease, defined as any of the following features: 1) ≥2 tender joints among a total of 78 joints assessed, and ≥2 swollen joints among a total of 76 joints assessed, 2) ≥2 digits with dactylitis and ≥1 joint with active inflammatory arthritis (swollen and tender) not associated with dactylitis, or 3) ≥2 sites of enthesitis (those judged by a physician as being severe) among a total of 29 sites assessed, with each site being distinct and not anatomically related to the same region and no bilateral involvement in the same site, or 4) ≥2 sites of enthesitis and ≥1 joint with active inflammatory arthritis (swollen and tender) not associated with enthesitis. In addition, patients were required to have a score of at least 40 mm on a 0–100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) for patient's global assessment of disease activity and patient's global assessment of pain. Moreover, they must have had an inadequate response to at least 2 NSAIDs or have been intolerant to, or had a contraindication for, NSAIDs. Patients with a score of ≥20 mm on the VAS for total back pain (scale 0–100 mm) were excluded from the study. Patients with previous exposure to biologic therapy were also excluded.

Study design and treatment

The ABILITY-2 study, initiated in March 2010, is an ongoing phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial being conducted at 28 centers in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the US. The study has been performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of an institutional ethics review board and voluntary written informed consent were obtained prior to the initiation of study procedures.

Eligible patients were centrally randomized using an interactive voice or web-based response system. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive adalimumab 40 mg every other week subcutaneously or matching placebo for 12 weeks during the double-blind period. Efficacy and safety were assessed at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. The double-blind period was followed by an ongoing 144-week open-label period during which patients received adalimumab 40 mg every other week.

Patients could enter the study while continuing to receive concomitant treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (methotrexate ≤25 mg per week, sulfasalazine ≤3 gm per day, and/or hydroxychloroquine ≤400 mg per day or azathioprine ≤150 mg per day) and/or NSAIDs, if the doses met prespecified stability requirements prior to randomization and remained stable during the first 12 weeks of the trial, except when changes were medically required due to an adverse event (AE).

Efficacy assessments

Primary efficacy end point

Given the paucity of clinical trials conducted to date in patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA, no efficacy end point that represents a measure of improvement in arthritis, enthesitis, and/or dactylitis has been specifically developed for and validated in this population. Therefore, a novel composite efficacy outcome measure was designed as the primary end point for this study: the proportion of patients who achieved the Peripheral SpA Response Criteria (PSpARC40) at week 12. The PSpARC40 was defined as ≥40% improvement (≥20-mm absolute improvement) from baseline in the VAS scores for patient's global assessment of disease activity and patient's global assessment of pain, and ≥40% improvement from baseline in at least one of the following features: 1) swollen joint count (SJC) (total of 76 joints assessed) and tender joint count (TJC) (total of 78 joints assessed), 2) total enthesitis count, or 3) dactylitis count. The total enthesitis count represents the sum of all unique, individual sites exhibiting enthesitis, comprising the anatomic locations included in the Leeds Enthesitis Index (17), the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index (18), and the Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) (19).

Secondary efficacy end points

Secondary efficacy variables analyzed at week 12 included physician's global assessment of disease activity (0–100-mm VAS), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI; scale 0–10) (20), the Health Assessment Questionnaire modified for the Spondyloarthropathies (HAQ-S) (21), and the Short-Form 36 version 2 (SF-36v2) Health Survey physical component summary (PCS) score (22). Other variables analyzed at various time points included the enthesitis assessment, consisting of the Leeds Enthesitis Index (scale 0–6) (17), SPARCC Enthesitis Index (scale 0–16) (18), and MASES (scale 0–13) (19), the dactylitis count, the TJC and SJC, and the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) (23).

In addition to the PSpARC40, different cutoff values defining levels of improvement, including proportions of patients achieving 20% (PSpARC20), 50% (PSpARC50), and 70% (PSpARC70) levels of improvement, were also evaluated. The PSpARC20, PSpARC50, and PSpARC70 were defined as ≥20%, ≥50%, and ≥70% improvement from baseline (≥10-mm, ≥20-mm, or ≥30-mm absolute improvement), respectively, in the VAS scores for patient's global assessment of disease activity and patient's global assessment of pain, and ≥20%, ≥50%, and ≥70% improvement from baseline, respectively, in at least one of the following features: the TJC and SJC, total enthesitis count, or dactylitis count.

Disease remission was evaluated using two composite measures, the ASDAS and the PSpARC. Inactive disease based on the ASDAS was defined as an ASDAS score of <1.3 (24). Disease remission based on the PSpARC criteria was defined as an SJC of ≤1 and at least 4 of the 5 following parameters: patient's global assessment of disease activity VAS score ≤20 mm, patient's global assessment of pain VAS score ≤20 mm, TJC ≤1, total enthesitis count ≤1, or dactylitis count ≤1.

Safety assessments

Safety was assessed by evaluating the frequency of AEs that began or worsened after the first dose of study medication through 70 days after the last dose.

Statistical analysis

The intent-to-treat population analyzed for efficacy and safety included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication. A sample size of 154 patients (77 for the placebo group and 77 for the adalimumab group) was calculated to provide ∼90% statistical power to detect a 25% difference in PSpARC40 response rates between the treatment groups, based on a Pearson's 2-sided chi-square test with a level of significance of α = 0.05.

For categorical variables, patients with missing data at week 12 were considered to be nonresponders, as determined using nonresponder imputation. Last observation carried forward–imputed values were used for missing continuous variables at week 12. Analysis of covariance, adjusted for the baseline score, was used to compare change from baseline to week 12 between the adalimumab and placebo treatment groups.

To determine the impact of baseline characteristics on the primary end point, analysis of treatment effect by various subgroups was performed for the following demographic features and baseline disease characteristics: age, sex, weight, SpA features (evidence of preceding infection, history of IBD, or anterior uveitis), HLA–B27 status, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) level, and concomitant use of DMARDs or NSAIDs. The Breslow-Day test of homogeneity (odds ratio) was used to compare treatment effect between the subgroups. If the differences were significant (P ≤ 0.10), a Mantel-Haenszel test was used to investigate the treatment effect within each subgroup.

AEs were defined using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 14.0) system organ classes and preferred terms. AEs were summarized as the number and percentage of patients experiencing AEs.

Results

Disposition of treatment groups and baseline characteristics of the patients

There were 165 patients randomized into the study, of whom 81 were randomized to receive placebo and 84 to receive adalimumab. During the 12-week double-blind period, 2 patients discontinued the study, both of whom were in the adalimumab group. One patient discontinued due to the occurrence of an AE (whole-body dermatitis) and another patient withdrew consent.

The demographic features and baseline disease characteristics of the patients were generally comparable between the treatment groups (Table1), except that the mean age was higher in the adalimumab group, and the percentage of patients with a dactylitis count ≥1 was lower in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group. There were more women than men in the study population. A mean delay of ∼4 years was noted between symptom onset and SpA diagnosis. At study entry, the majority of patients were taking a concomitant NSAID and almost one-half of the patients were taking a concomitant DMARD. In total, 61% of patients (56% of the placebo group, 67% of the adalimumab group) were positive for HLA–B27.

Table 1.

Demographic features and baseline disease characteristics of the study patients*

| Placebo (n = 81) | Adalimumab (n = 84) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 42 (52) | 48 (57) |

| White | 81 (100) | 83 (99) |

| Age, mean ± SD years | 38.5 ± 12.8 | 42.5 ± 10.8 |

| Disease characteristics | ||

| Symptom duration, mean ± SD years | 6.6 ± 6.3 | 7.7 ± 7.9 |

| Duration since SpA diagnosis, mean ± SD years | 3.0 ± 5.0 | 4.2 ± 5.6 |

| Prior NSAID use | 80 (99) | 82 (98) |

| Concomitant NSAID use at baseline | 65 (80) | 57 (68) |

| Prior DMARD use | 56 (69) | 58 (69) |

| Concomitant DMARD use at baseline | 40 (49) | 38 (45) |

| Methotrexate | 23 (28) | 22 (26) |

| Sulfasalazine | 25 (31) | 19 (23) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0 | 3 (4) |

| HLA–B27 positive | 45 (56) | 56 (67) |

| SpA features | ||

| Anterior uveitis, past or present | 11 (14) | 14 (17) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease, past or present | 3 (4) | 5 (6) |

| Preceding infection† | 10 (12) | 3 (4) |

| Family history of SpA | 20 (25) | 23 (27) |

| Patient's global assessment of disease activity (0–100-mm VAS), mean ± SD | 66 ± 15.9 | 65 ± 15.2 |

| Patient's global assessment of pain (0–100-mm VAS), mean ± SD | 66 ± 15.9 | 64 ± 14.0 |

| Physician's global assessment of disease activity (0–100-mm VAS), mean ± SD | 57 ± 15.0 | 60 ± 15.5 |

| Tender joints | ||

| ≥1 tender joint | 80 (99) | 83 (99) |

| Tender joint count (total 78 joints assessed), mean ± SD | 13.6 ± 16.1 | 13.0 ± 12.8 |

| Swollen joints | ||

| ≥1 swollen joint | 76 (94) | 78 (93) |

| Swollen joint count (total 76 joints assessed), mean ± SD | 7.3 ± 8.0 | 6.1 ± 5.6 |

| Predominantly lower limb involvement of arthritis‡ | 45 (56) | 43 (51) |

| Dactylitis | ||

| ≥1 dactylitis site | 24 (30) | 13 (16) |

| Dactylitis count, mean ± SD | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.4 ± 0.9 |

| Enthesitis | ||

| ≥1 enthesitis site | 73 (90) | 70 (83) |

| Total enthesitis count (total 29 sites assessed), mean ± SD§ | 7.3 ± 6.7 | 6.7 ± 7.0 |

| Leeds Enthesitis Index (scale 0–6), mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.7 |

| SPARCC Enthesitis Index (scale 0–16), mean ± SD | 4.1 ± 3.8 | 3.8 ± 4.0 |

| MASES (scale 0–13), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 3.4 | 3.1 ± 3.6 |

| BASDAI (scale 0–10), mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.7 |

| ASDAS, mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 0.8¶ | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| Elevated hsCRP level | 37 (46) | 35 (42) |

| SF-36v2 PCS score (scale 0–100), mean ± SD | 34.5 ± 7.6 | 34.6 ± 7.9 |

| HAQ-S score (scale 0–3), mean ± SD | 1.00 ± 0.5 | 0.97 ± 0.5 |

The percentages of patients with other clinical manifestations or features associated with SpA were similar in both treatment groups at baseline, except that there were more patients with a history of preceding infection characteristic of ReA in the placebo group. At baseline, current peripheral arthritis and/or enthesitis was more prevalent than dactylitis, as evidenced by the proportion of patients with a TJC ≥1, SJC ≥1, total enthesitis count ≥1, and dactylitis count ≥1. Moderate to high disease activity was noted in both treatment groups, based on the mean VAS scores for patient's and physician's global assessments of disease activity and on the BASDAI and ASDAS scores, and more than 40% of patients had an elevated hsCRP level at baseline. The baseline SF-36v2 PCS scores indicated impaired physical function and poorer health-related quality of life in this patient population compared to the general population in the US (26).

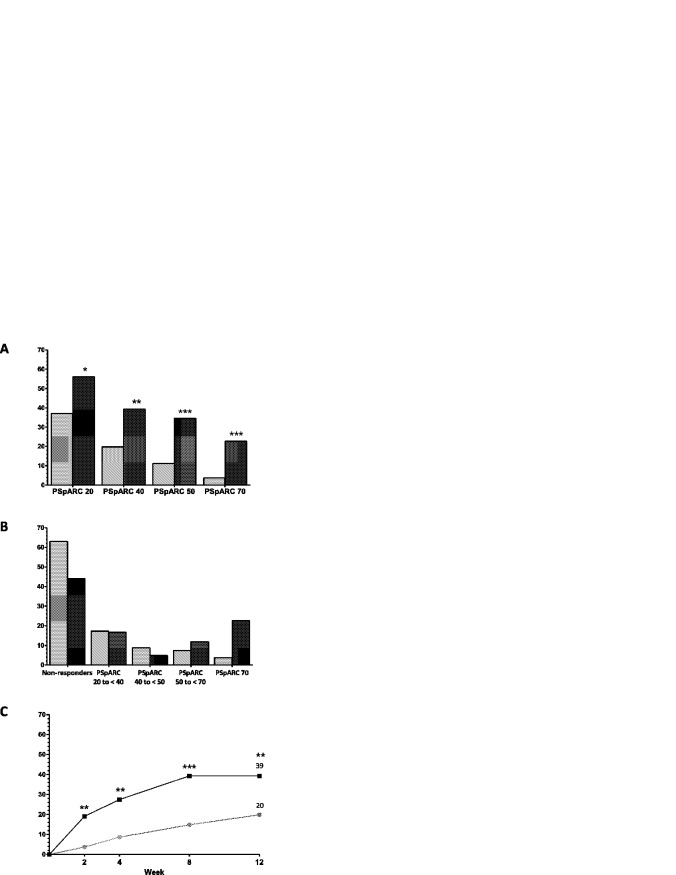

Efficacy

A significantly greater percentage of patients with peripheral SpA treated with adalimumab achieved a PSpARC40 response at week 12 compared to patients treated with placebo (33 [39%] of 84 versus 16 [20%] of 81; P = 0.006, nonresponder imputation) (Figure 1A). A significant difference (P < 0.01) was observed as early as week 2 (Figure 1C). The proportions of patients meeting the PSpARC20, PSpARC50, and PSpARC70 response levels at week 12 were also significantly greater in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group (Figure 1A). Evaluation of PSpARC response rates based on nonoverlapping categories indicated that of those patients who met the primary end point, the PSpARC40, in the adalimumab group, the majority were PSpARC50 and PSpARC70 responders (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Improvement in disease activity as measured by the Peripheral SpondyloArthritis Response Criteria (PSpARC) in patients treated with adalimumab (dark-shaded bars and squares) compared to those receiving placebo (light-shaded bars and circles). A and B, PSpARC response rates measured according to 20% (PSpARC20), 40% (PSpARC40; the primary end point), 50% (PSpARC50), and 70% (PSpARC70) levels of improvement at week 12 (A), and PSpARC response rates presented as nonoverlapping categories (B) (placebo n = 81, adalimumab n = 84). C, PSpARC40 response rates in each treatment group over time. ∗ = P < 0.05; ∗∗ = P < 0.01; ∗∗∗ = P < 0.001 versus placebo (nonresponder imputation).

Based on analyses of treatment effect by various subgroups, the only significant subgroup predictor of response to adalimumab was the baseline hsCRP level (P = 0.076 by Breslow-Day test, nonresponder imputation). Among patients with an elevated hsCRP level at baseline, 51% of adalimumab-treated patients compared to 16% of placebo-treated patients were PSpARC40 responders at week 12 (P = 0.002, nonresponder imputation), while among those with a normal hsCRP level at baseline, 31% of adalimumab-treated patients compared to 23% of placebo-treated patients achieved a PSpARC40 response (P = 0.394, nonresponder imputation).

Among patients who achieved a PSpARC40 response, fulfillment of the response criteria was primarily due to improvement in the following components: patient's global assessment of disease activity VAS score, patient's global assessment of pain VAS score, and the TJC and SJC. A ≥40% improvement and at least 20-mm improvement in the VAS score for patient's global assessment of disease activity (adalimumab 54% versus placebo 29%; P < 0.001) and patient's global assessment of pain (adalimumab 54% versus placebo 31%; P = 0.004), and at least 40% improvement in the TJC and SJC (adalimumab 57% versus placebo 30%; P < 0.001) were observed more frequently in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group. There was no significant difference between the treatment groups with regard to improvement in the total enthesitis count (adalimumab 51% versus placebo 42%; P = 0.237) and the dactylitis count (adalimumab 14% versus placebo 19%; P = 0.392).

Mean improvements in some of the individual components of the PSpARC40 (patient's global assessments of disease activity and pain, TJC, SJC, and total enthesitis count) were significantly greater with adalimumab treatment compared to placebo (Table2). The mean change in the dactylitis count was not significantly different between the groups. However, only a few patients had dactylitis at baseline (n = 13 in the adalimumab group and n = 24 in the placebo group; mean baseline dactylitis count 2.2 in the adalimumab group and 2.2 in the placebo group).

Table 2.

Mean change from baseline in efficacy variables at week 12*

| Placebo (n = 81) | Adalimumab (n = 84) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient's global assessment of disease activity (0–100-mm VAS) | −16.4 ± 24.5 | −27.5 ± 25.8 | 0.003 |

| Patient's global assessment of pain (0–100-mm VAS) | −17.1 ± 24.3 | −28.9 ± 24.7 | 0.001 |

| Tender joint count | −1.8 ± 8.4 | −5.9 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Swollen joint count | −3.1 ± 5.6 | −3.6 ± 4.3 | 0.045 |

| Total enthesitis count | −1.5 ± 4.0 | −2.8 ± 3.9 | 0.008 |

| Dactylitis count | −0.3 ± 0.9 | −0.2 ± 1.1 | 0.808 |

| Physician's global assessment of disease activity (0–100-mm VAS) | −18.2 ± 22.9 | −32.2 ± 22.5 | <0.001 |

| BASDAI | −1.0 ± 2.2 | −2.1 ± 2.3 | 0.003 |

| HAQ-S score | −0.2 ± 0.5 | −0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.051 |

| SF-36v2 PCS score† | 2.4 ± 6.7 | 6.7 ± 7.9 | <0.001 |

| hsCRP level, mg/liter | −2.9 ± 11.0 | −5.5 ± 18.4 | 0.021 |

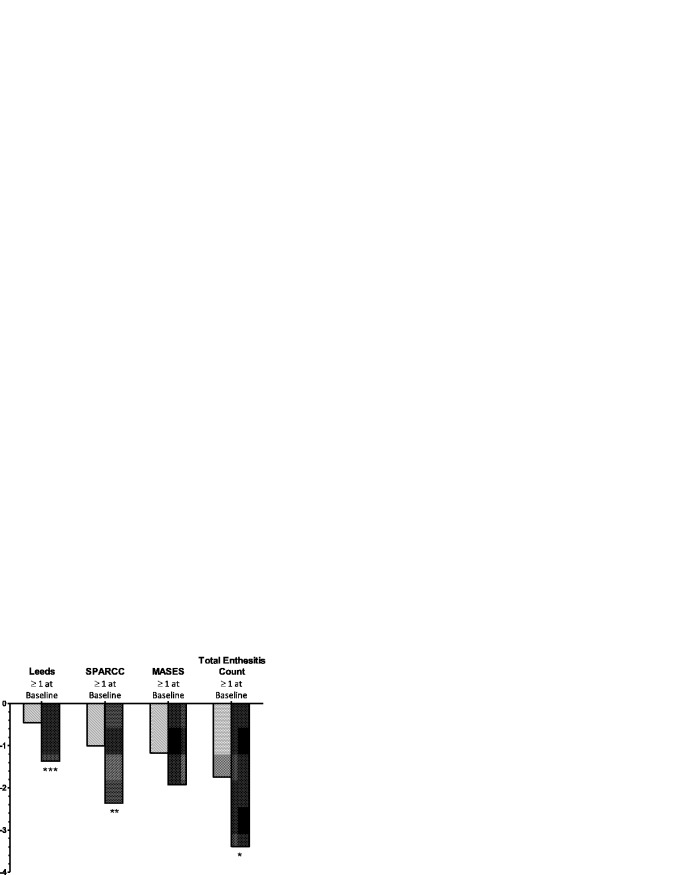

Other measures of disease activity were also noted to improve by week 12, such as the mean change in the physician's global assessment of disease activity, BASDAI, and hsCRP level (Table2). Improvement in physical function and health-related quality of life, as measured by the SF-36v2 PCS, was observed to be significantly greater in patients receiving adalimumab compared to those receiving placebo (P < 0.001), but no significant difference in the HAQ-S scores at week 12 was observed between the adalimumab and placebo groups. Among patients who had evidence of enthesitis at baseline (baseline score ≥1 for the specific enthesitis index evaluated), significant improvement was observed with adalimumab as compared to placebo in the Leeds and SPARCC scores for enthesitis and the total enthesitis count, but not in the MASES (Figure 2). Similarly, among patients who had a dactylitis count ≥1 at baseline, the mean change in dactylitis count at week 12 was numerically higher in the adalimumab group (mean change −1.6) compared to the placebo group (mean change −1.3; P = 0.498).

Figure 2.

Improvement in enthesitis among patients with an enthesitis score of ≥1 at baseline. The mean change in enthesitis from baseline to week 12 in patients treated with adalimumab (dark-shaded bars) compared to those receiving placebo (light-shaded bars) was determined among patients with a baseline enthesitis score of ≥1, using the Leeds Enthesitis Index (placebo n = 51, adalimumab n = 52), the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index (placebo n = 65, adalimumab n = 64), the Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) (placebo n = 65, adalimumab n = 58), and the total enthesitis count (placebo n = 73, adalimumab n = 70). Last observation carried forward was used for all mean change values. ∗ = P < 0.05; ∗∗ = P < 0.01; ∗∗∗ = P < 0.001 versus placebo.

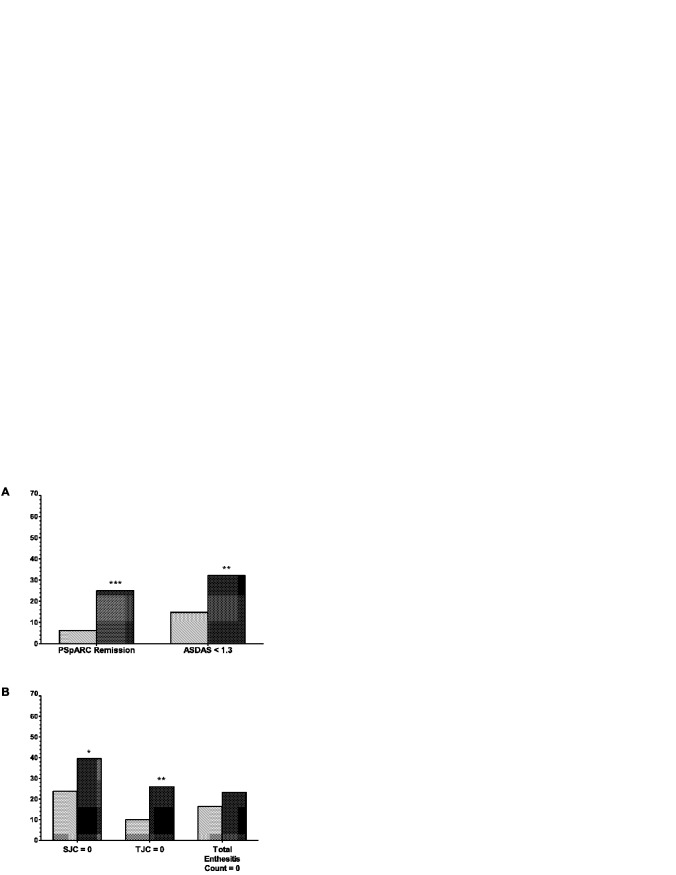

The proportions of patients considered to have achieved disease remission (according to the PSpARC criteria) or inactive disease (according to an ASDAS score <1.3) at week 12 were significantly greater in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group (Figure 3A). In patients with an SJC ≥1 or TJC ≥1 at baseline, more patients had absence of swollen or tender joints (i.e., achieving an SJC or TJC equal to 0) by week 12 in the adalimumab group compared to the placebo group (Figure 3B). Moreover, among the patients with a dactylitis count ≥1 at baseline (placebo n = 24, adalimumab n = 13), 85% in the adalimumab group had a dactylitis count of 0 at week 12 compared to 58% in the placebo group.

Figure 3.

Measures of disease remission at week 12. A, Remission rates in each treatment group (adalimumab [n = 84] [dark-shaded bars] versus placebo [n = 81] [light-shaded bars]) at week 12 were determined according to the Peripheral SpondyloArthritis Response Criteria (PSpARC), and rates of inactive disease at week 12 were determined according to the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), defined as an ASDAS score of <1.3. ∗∗ = P < 0.01; ∗∗∗ = P < 0.001 versus placebo (nonresponder imputation). B, Proportions of patients with a baseline value of ≥1 achieving a value of 0 at week 12 were determined for the swollen joint count (SJC) (placebo n = 76, adalimumab n = 76), tender joint count (TJC) (placebo n = 80, adalimumab n = 81), and total enthesitis count (placebo n = 73, adalimumab n = 69). ∗ = P < 0.05; ∗∗ = P < 0.01 versus placebo (observed data).

Safety

The overall incidence of any AE in the adalimumab group was similar to that in the placebo group during the double-blind period (Table3). The most common events (MedDRA preferred terms) were nasopharyngitis (14%), upper respiratory tract infection (5%), and diarrhea (5%) among patients in the placebo group, and spondyloarthropathy (representing flare of SpA) (7%), nasopharyngitis (5%), upper respiratory tract infection (5%), and headache (5%) in the adalimumab group. There were 2 serious AEs. A patient in the placebo group experienced left-sided thoracic pain that lasted for only 1 day. A patient in the adalimumab group took an overdose of acetaminophen.

Table 3.

Incidence and types of treatment-emergent AEs during the 12-week double-blind period*

| Placebo (n = 81) | Adalimumab (n = 84) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 44 (54) | 46 (55) |

| Serious AE | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| AE leading to discontinuation of study drug | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Infectious AE | 23 (28) | 18 (21) |

| Serious infection | 0 | 0 |

| Parasitic infection other than opportunistic infection | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hepatic-related AE | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Elevated ALT level–related AE | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Hematologic AE | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

Two patients had an AE during the double-blind period that led to discontinuation from the study. One patient withdrew due to the development of whole-body dermatitis. The other patient withdrew because of the development of acarodermatitis (scabies) that had started during the double-blind period, but the patient completed week 12 and discontinued during the open-label period. No serious infections, opportunistic infections, tuberculosis, malignancies, demyelinating disease, or deaths were reported through week 12.

Discussion

This study is the first to use the ASAS peripheral SpA criteria to classify patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA and is the largest randomized controlled trial of an anti-TNF therapy in this population. Findings in this report contribute to the growing knowledge and understanding of the SpA group of diseases. Among patients enrolled in this trial, few had a preceding infection characteristic of ReA. The proportion of patients with accompanying IBD was also low, although it was within the same range as that reported in typical phase III anti-TNF trials in patients with AS (25,26). This indicates that the majority of patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA in this trial would have been categorized as having uSpA if the historical disease classification of SpA had been used. Therefore, this study has demonstrated the potential benefit of adalimumab in a group of SpA patients who were previously excluded from trials of anti-TNF agents for the treatment of AS or PsA.

The nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA patient population enrolled in this trial was younger and had a greater proportion of women compared to the PsA study population enrolled in clinical trials of anti-TNF therapy (10–13). The mean age at study entry was ∼40 years, with ∼4 years between symptom onset and diagnosis. This delay may be due to underdiagnosis of this disease population. The mean TJC and SJC were also lower (13 and 7, respectively) compared to those in patients with PsA (TJC range 20–26 and SJC range 12–15) (10,11,13) and were predominantly in the lower limbs in more than 50% of the patients. However, the baseline values for patient's and physician's global assessments of disease activity and the HAQ-S in this study indicate that the levels of disease activity and functional impairment were comparable between patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA and patients with PsA (10–12). The proportion of patients with enthesitis at baseline and the enthesitis index scores suggest that in addition to peripheral arthritis, enthesitis may have a substantial contribution to the overall burden of disease in nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA.

This study demonstrated that 39% of patients in the adalimumab group achieved the primary end point of PSpARC40 response compared to 20% of patients in the placebo group. These results suggest that the novel composite end point of the PSpARC40, which was developed specifically for this nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA population, performs well in discriminating the efficacy of the active drug from the placebo treatment in this population while enabling a comprehensive evaluation of disease activity. Other cutoff values for the PSpARC response (PSpARC20, PSpARC50, and PSpARC70) were also tested, and similar effect sizes across all 4 PSpARC response thresholds were observed. Based on subgroup analyses, the presence of an elevated hsCRP level at baseline was the only significant predictor of the PSpARC40 response to adalimumab therapy at week 12.

Consistent with previously published reports on the benefits of anti-TNF therapy in enthesitis (27,28), significant improvement in enthesitis was demonstrated following treatment with adalimumab, as indicated by the Leeds and SPARCC enthesitis indices but not by the MASES. The MASES was developed for the AS population (19) and assesses sites of entheses in primarily axial locations, in contrast to the Leeds and SPARCC indices, and thus may not be as suitable for a peripheral SpA population (17,18). Baseline enthesitis scores were low, as were the baseline dactylitis counts. Fewer than 25% of patients had dactylitis at baseline. Thus, no treatment effect on the dactylitis count was noted at week 12.

Composite measures that have been used previously in clinical trials of AS were also noted to discriminate between active drug and placebo in the present study. The mean change in the BASDAI and ASDAS inactive disease response rates were better in patients treated with adalimumab compared to those receiving placebo. This may be largely attributed to the components that reflect involvement of the peripheral joints and entheses. These observations are consistent with the findings in a study by Paramarta et al, in which the BASDAI50 score (adalimumab 42% versus placebo 5%) and ASDAS inactive disease score (adalimumab 42% versus placebo 0%) showed significant improvements in those treated with adalimumab compared to those receiving placebo after 12 weeks of therapy (14). In addition to the ASDAS category of inactive disease, clinical remission was measured using the PSpARC remission criteria, with the results demonstrating that the frequency of disease remission was higher among patients treated with adalimumab. Furthermore, in the adalimumab group, significant improvement in function and health-related quality of life, as measured using the SF-36v2 PCS, was also observed.

Adalimumab was well tolerated during the 12-week double-blind study period in this study population. There were only 2 serious AEs, and there were no serious infections, tuberculosis, malignancies, or deaths. No new safety signal was observed during the 12-week double-blind period beyond what is already known about the safety profile of adalimumab in SpA (AS (25), PsA (10), and nonradiographic axial SpA (29)) and other immune-mediated diseases (30).

Limitations of this study include the duration of the double-blind period, which did not allow for a longer-term analysis of the efficacy of adalimumab compared to placebo in this patient population. Longer observation is also needed to better characterize the safety of adalimumab in patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA. The primary efficacy end point, the PSpARC40, has not been validated in other peripheral SpA cohorts. However, validation of this outcome measure is ongoing. Other cutoff levels (e.g., the PSpARC50) might better differentiate between active drug and placebo. The BASDAI and ASDAS are validated for patients with AS, but not for patients with peripheral SpA; however, most of the components used to calculate the ASDAS are applicable to a peripheral SpA population.

Patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA can benefit from alternative, more effective treatment options. After 12 weeks, adalimumab significantly ameliorated the signs and symptoms of disease and improved physical function in patients with active nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA who had experienced an inadequate response or intolerance to NSAIDs. The safety profile of adalimumab in this patient population was consistent with the well-established safety of adalimumab in multiple immune-mediated diseases. Longer-term data are needed to confirm and support the current findings of a favorable benefit–risk profile of adalimumab in patients with nonpsoriatic peripheral SpA.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Pangan had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Mease, Sieper, Karunaratne, Pangan.

Acquisition of data. Mease, Sieper, Van den Bosch, Rahman, Karunaratne, Pangan.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Mease, Sieper, Van den Bosch, Rahman, Karunaratne, Pangan.

Role of the Study Sponsor

AbbVie funded the study, participated in the design of the study, and contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and to the writing and review of the manuscript and approval to submit the manuscript for publication. Medical writing support was provided by Kathleen V. Kastenholz, PharmD, MS, an employee of AbbVie.

References

- 1.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Chou CT. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palm O, Moum B, Jahnsen J, Gran JT. The prevalence and incidence of peripheral arthritis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a prospective population-based study (the IBSEN study) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:1256–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.11.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen S, Bendtzen K, Nielsen OH. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2010;42:97–114. doi: 10.3109/07853890903559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. et al, for the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannu T, Mattila L, Siitonen A, Leirisalo-Repo M. Reactive arthritis attributable to Shigella infection: a clinical and epidemiological nationwide study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:594–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.027524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Leirisalo-Repo M, Huitfeldt B, Juhlin R, Veys E. Sulfasalazine in the treatment of spondylarthropathy: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:618–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380507. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saraux A, Guedes C, Allain J, Devauchelle V, Vallis I, Lamour A Société de Rhumatologie de l'Ouest. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathy in Brittany, France. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2622–7. et al, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akkoc N. Are spondyloarthropathies as common as rheumatoid arthritis worldwide? A review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:371–8. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Reitchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH Adalimumab Effectiveness in Psoriatic Arthritis Trial Study Group. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3279–89. doi: 10.1002/art.21306. et al, for the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoni CE, Kavanaugh A, Kirkham B, Tutuncu Z, Burmester GR, Schneider U. Sustained benefits of infliximab therapy for dermatologic and articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis: results from the Infliximab Multinational Psoriatic Arthritis Controlled Trial (IMPACT) Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1227–36. doi: 10.1002/art.20967. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:385–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, Krueger GG, Gladman D, Gomez-Reino J. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor α antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis: twenty-four–week efficacy and safety results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:976–86. doi: 10.1002/art.24403. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paramarta JE, De Rycke L, Heijda TF, Ambarus CA, Vos K, Dinant HJ. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab for the treatment of peripheral arthritis in spondyloarthritis patients without ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1793–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202245. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A European Spondylarthropathy Study Group. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1218–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003. et al, the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis: a proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healy PJ, Helliwell PS. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:686–91. doi: 10.1002/art.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maksymowych WP, Mallon C, Morrow S, Shojania K, Olszynski WP, Wong RL. Development and validation of the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:948–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084244. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Spoorenberg A, van Tubergen A, Landewe R, van der Tempel H, Mielants H. Assessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:127–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.2.127. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Roberts NW, Liang MH. A modification of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for the spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:946–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE. Jr. SF-36 Health Survey update. URL: http://www.sf-36.org/tools/sf36.shtml. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lukas C, Landewe R, Sieper J, Dougados M, Davis J, Braun J Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:18–24. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094870. et al, for the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machado P, Landewe R, Lie E, Kvien TK, Braun J, Baker D. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138594. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, Sieper J, Dijkmans BA, Braun J ATLAS Study Group. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2136–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21913. et al, for the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P Ankylosing Spondylitis Study for the Evaluation of Recombinant Infliximab Therapy Study Group. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT) Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:582–91. doi: 10.1002/art.20852. et al, and the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dougados M, Combe B, Braun J, Landewe R, Sibilia J, Cantagrel A. A randomised, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of etanercept in adults with refractory heel enthesitis in spondyloarthritis: the HEEL study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1430–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121533. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R. Persistent clinical response to the anti-TNF-α antibody infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 3 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:670–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh584. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Mease PJ, Maksymowych WP, Brown MA. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial (ABILITY-1) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:815–22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201766. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, McIlraith MJ, Lacerda AP. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23,458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:517–24. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]