Depression and subsequent risk of Parkinson disease: A nationwide cohort study (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the long-term risk of Parkinson disease (PD) after depression and evaluate potential confounding by shared susceptibility to the 2 diagnoses.

Methods:

The nationwide study cohort included 140,688 cases of depression, matched 1:3 using a nested case-control design to evaluate temporal aspects of study parameters (total, n = 562,631). Potential familial coaggregation of the 2 diagnoses was investigated in a subcohort of 540,811 sibling pairs. Associations were investigated using multivariable adjusted statistical models.

Results:

During a median follow-up period of 6.8 (range, 0–26.0) years, 3,260 individuals in the cohort were diagnosed with PD. The multivariable adjusted odds ratio (OR) for PD was 3.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.5–4.1) within the first year of depression, decreasing to 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1–2.0) after 15 to 25 years. Among participants with depression, recurrent hospitalization was an independent risk factor for PD (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9 for ≥5 vs 1 hospitalization). In family analyses, siblings' depression was not significantly associated with PD risk in index persons (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.9–1.4).

Conclusions:

The time-dependent effect, dose-response pattern for recurrent depression, and lack of evidence for coaggregation among siblings all indicate a direct association between depression and subsequent PD. Given that the association was significant for a follow-up period of more than 2 decades, depression may be a very early prodromal symptom of PD, or a causal risk factor.

Depression is more common in patients with Parkinson disease (PD) than in the general population.1,2 It is a major factor for health-related quality of life in patients with PD, and may also be associated with more rapid deterioration in cognitive and motor functions.3 Many studies have reported an increased prevalence of depression in these patients before the clinical onset of PD, suggesting that psychological reactions to this disease cannot entirely explain the relationship.4–14 Various neurobiological hypotheses have suggested that depression is an independent risk factor or early symptom of PD, or that the association between depression and PD reflects shared etiologic factors, mimicking a causal relationship.12,15,16 An increased prevalence of mental illness among relatives of patients with PD has also been reported,15 suggesting a shared genetic susceptibility, but such associations have not been widely investigated.

The relationship between depression and subsequent PD appears to be strongest in the few years preceding the onset of motor symptoms,11–13 but it may exist earlier.5,12,13 Few studies have investigated temporal perspectives of >10 years, and long-term findings have been inconclusive.6,12,14 The onset of cardinal motor symptoms in PD is preceded by substantial neurodegeneration,17,18 but the duration of the prodromal phase is unknown; estimates range from a few years to 2 or more decades.19 Better knowledge of time perspectives and features of the association between depression and PD could improve the ability to understand the underlying etiology, which would be of great value given the impact of depression on quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with PD.3

In the present study, we investigated long-term associations between depression and subsequent PD and evaluated potential confounding familial factors. We used a nationwide cohort of 3.3 million participants, including >140,000 cases of depression, and 25 years of reliable registry data for continuous follow-up to evaluate time perspectives in a nested case-control (NCC) cohort and familial factors in a subcohort of >540,000 full-sibling pairs.

METHODS

Study population.

The cohort considered for inclusion in the present study consisted of all Swedish citizens aged ≥50 years as of December 31, 2005 (n = 3,329,400). Unique personal identification numbers were used to obtain information from the registers listed below. Diagnoses for the periods 1987–1997 and 1998–2012 were coded according to the Swedish versions of the ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively.

Diagnoses of depression (ICD-9 code 311, ICD-10 code F32 or F33) and PD (ICD-9 code 332A, ICD-10 code G209) between January 1, 1987, and December 31, 2012, were acquired from the National Patient Register (NPR),20 administered by the Center for Epidemiology of Sweden's National Board of Health and Welfare. This register has provided records of all public inpatient care in Sweden since 1987 and all specialist health care since 2001, where date of diagnosis corresponds to date of discharge from hospital or date of medical consultation for inpatient and outpatient diagnoses, respectively. In general, diagnoses recorded in the NPR have shown a high degree of validity, with positive predictive values of 85% to 97%,21 and in 2006, only 1% of all medical consultations/inpatient care events covered by the NPR had no main diagnosis registered.20 Information about deaths was obtained from the National Cause of Death Register.22

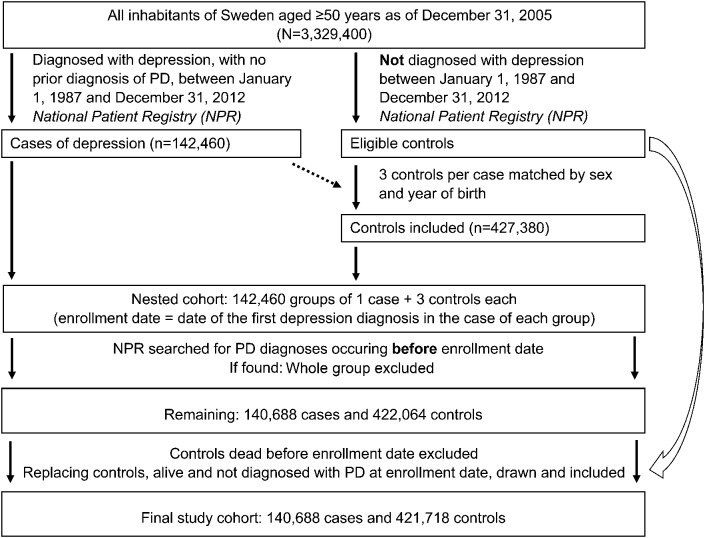

During the study period, 25,079 (0.8%) participants in the cohort were diagnosed with PD and 142,460 (4.3%) participants were diagnosed with depression with no prior diagnosis of PD. An NCC cohort was drawn, including all participants diagnosed with depression not preceded by PD and 3 controls, matched by sex and year of birth, per case. If any control subject within a matched group was diagnosed with PD before the date of enrollment (date of first depression diagnosis registered for the matching case), the whole group was excluded from analysis. Control participants who had died before the date of enrollment were excluded and replaced through a new matching process. After 5 attempts, all but 346 of these control participants had been replaced by another nondepressed subject, alive and free of PD at the date of enrollment. This left 140,688 cases of depression and 421,718 matched control participants who were included in the final NCC cohort (figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of nested case-control cohort selection.

PD = Parkinson disease.

Sibling cohort.

To investigate potential familial associations between depression and PD, a subcohort of sibling pairs was formed using the Swedish Multi-Generation Register,23 with family linkage information available for participants born in 1932 or thereafter. Selection was confined to full siblings and, to ensure that no subject was included twice in the analyses, one pair of siblings from each family was drawn; the final subcohort comprised 540,811 sibling pairs, where one sibling from each pair was included as index person in the analyses.

Additional covariates.

To adjust for other conditions related to depression24–29 that could potentially moderate an association between depression and PD, diagnoses of traumatic brain injury (_ICD_-9 codes 850–853, _ICD_-10 code S06), stroke (_ICD_-9 codes 431 and 434, _ICD_-10 codes I61–I64), alcohol dependency or abuse (_ICD_-9 codes 303 and 305A, _ICD_-10 code F10), drug dependency or abuse (_ICD_-9 codes 304 and 305X, _ICD_-10 codes F11–F19), and diabetes (_ICD_-9 code 250, _ICD_-10 codes E10 and E11) were acquired from the NPR and included in analyses if registered before the date of enrollment (in the NCC cohort) or with no preceding diagnosis of depression or PD (in the sibling cohort). Information about participants' education level (low, ≤9 years of primary or vocational school; high, university or ≥3 years of secondary school) was obtained from the Statistics Sweden database, and was available for 98.7% of participants.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents.

The local ethics committee of Umeå University and the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden approved the study protocol of the present study.

Statistical analyses.

The SPSS (version 21.0 for Windows; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Stata (version 12.1 for Macintosh; StataCorp, College Station, TX) software packages were used for statistical analyses, with p values <0.05 considered significant. Data are presented as valid percentages and mean values with SDs, unless otherwise indicated. Chi-square tests, t tests, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for univariate analyses.

The follow-up time for survival analyses was calculated from date of enrollment to date of PD diagnosis, death, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by a Cox model with Schoenfeld residuals, showing a time-dependent effect of depression in relation to the risk of PD (χ2 = 42.4, p < 0.001). Therefore, this association was further evaluated using a flexible parametric Royston–Parmar model30 with 3 degrees of freedom to investigate the association between depression and PD in the NCC cohort. The goodness of fit for the model was evaluated based on the Akaike information criterion. In addition to this graphic method, a conditional logistic regression model was used to investigate the odds ratios (ORs) for PD in different time intervals during the follow-up period. All models were adjusted for age, sex, education level, and comorbid diagnoses. The binary logistic regression analyses performed in the sibling cohort additionally included siblings' diagnoses of PD and depression as independent variables. Analyses were performed for the total sibling cohort and separately for same-sex sibling pairs.

To estimate the risk of PD in relation to the severity and duration/recurrence of preceding depression, we performed subgroup analyses including variables for inpatient (defined as any hospitalization for depression) vs outpatient care among participants first diagnosed with depression in 2001–2012, and for recurrent hospitalizations (>90 days after previous hospitalization) during the entire study period, respectively, in binary logistic regression models. Potential interactions between depression and other covariates were investigated by the stepwise inclusion of interaction terms in the logistic regression models described above.

RESULTS

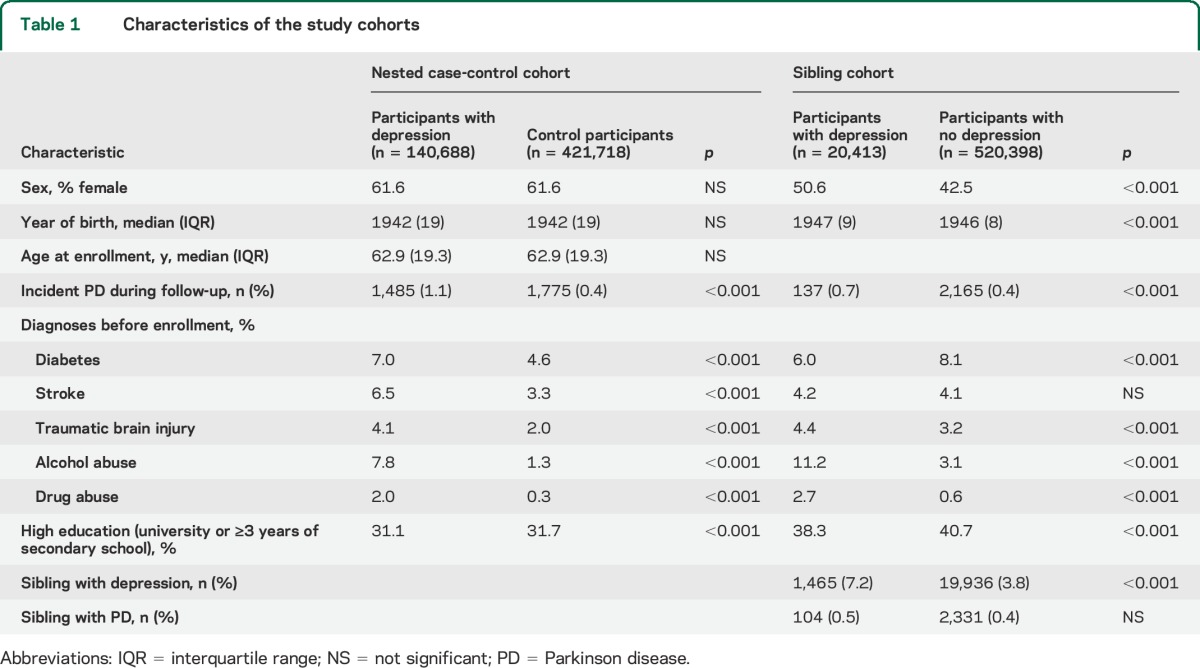

The final NCC cohort consisted of 562,631 participants (61.6% women) with a median age of 62.9 years at enrollment, and a median follow-up time of 6.8 (range, 0–26.0) years. In total, 3,260 (0.5%) participants were diagnosed with PD at a median of 4.5 (range, 0–24.9) years after enrollment; this group comprised 1,485 (1.1%) participants with depression and 1,775 (0.4%) control participants (p < 0.001) Diagnoses of diabetes, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and alcohol abuse were more common among participants with depression than among control participants, whereas high education level was less common (all p < 0.001; table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohorts

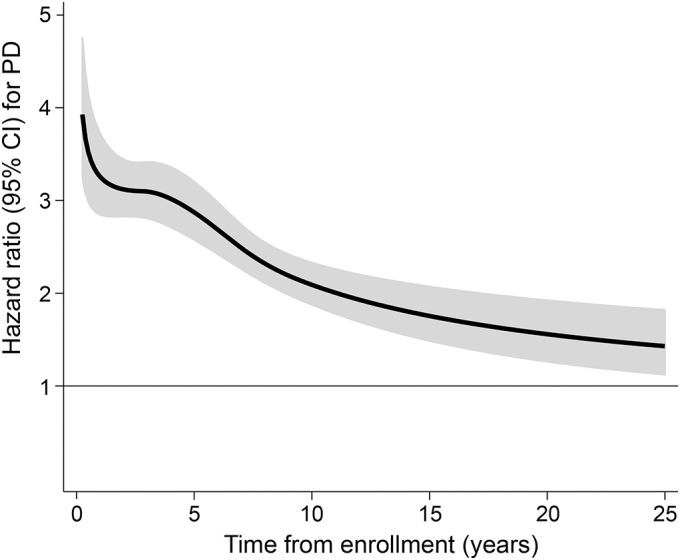

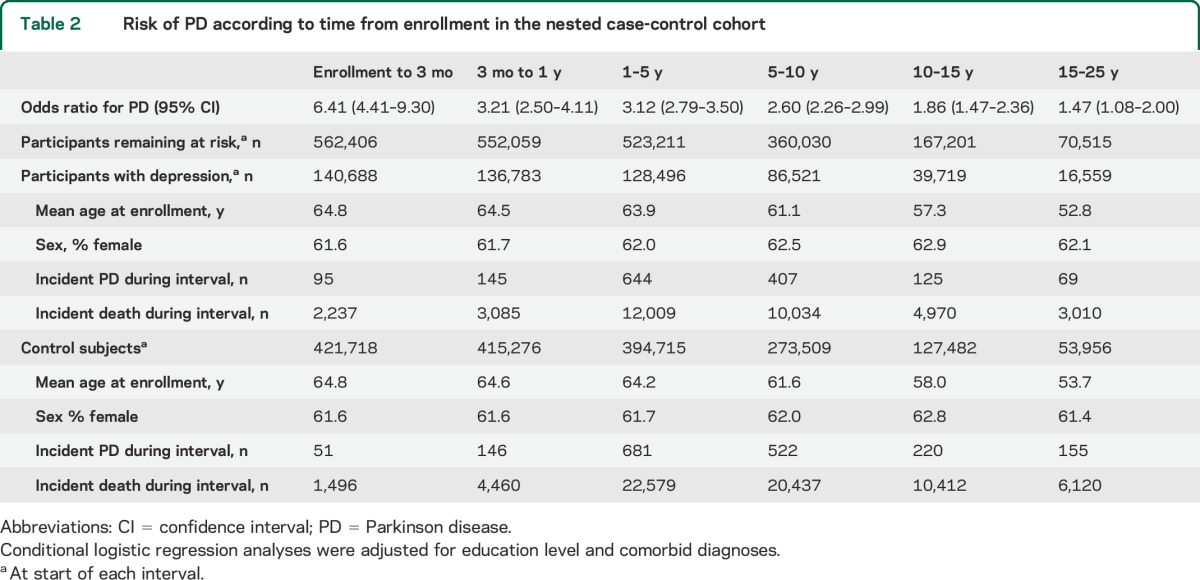

Estimated by flexible parametric survival analysis, the risk of PD was higher among participants with depression than among control participants; this association weakened over time but remained significant during the entire follow-up period (figure 2). These results were confirmed by conditional logistic regression for different time intervals, with ORs decreasing from 3.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.50–4.11) within 1 year of enrollment (excluding a lag time of 3 months) to 1.47 (95% CI, 1.08–2.00) after 15 to 25 years (table 2). Separate analyses for men and women yielded similar results, and no significant interaction between depression and other covariates (education level, comorbid diagnoses) was found regarding the risk of PD.

Figure 2. Risk of PD according to depression, from 3 months to 25 years after enrollment in the nested case-control cohort, estimated by a flexible parametric Royston–Parmar model adjusted for age, sex, education level, and comorbid diagnoses.

Hazard ratios with 95% CIs are presented. CI = confidence interval; PD = Parkinson disease.

Table 2.

Risk of PD according to time from enrollment in the nested case-control cohort

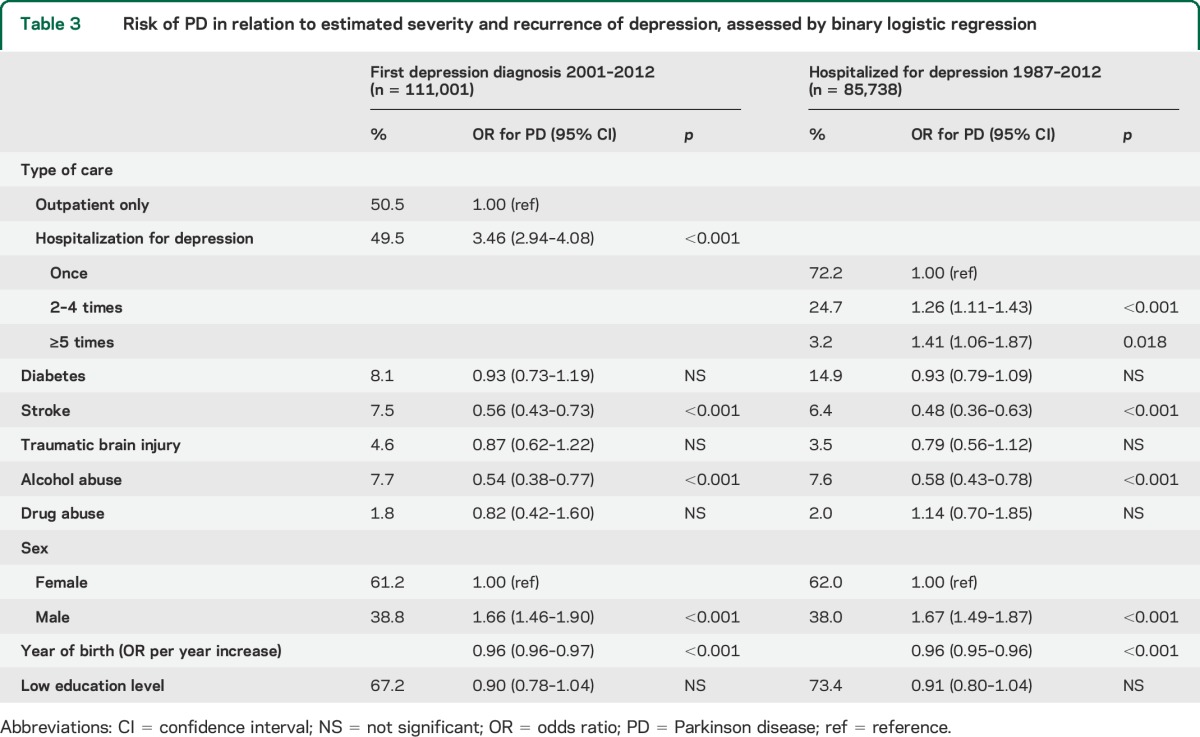

Among participants first diagnosed with depression between 2001 and 2012 (n = 111,001), the risk of PD was higher among those hospitalized for depression (OR, 3.46; 95% CI, 2.94–4.08) than among those who received only outpatient care. Among participants ever hospitalized for depression between 1987 and 2012 (n = 85,738), the risk of PD increased with the number of care events (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.12–1.41 for 2–4 hospitalizations; OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.06–1.87 for ≥5 hospitalizations, compared with a single care event; table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of PD in relation to estimated severity and recurrence of depression, assessed by binary logistic regression

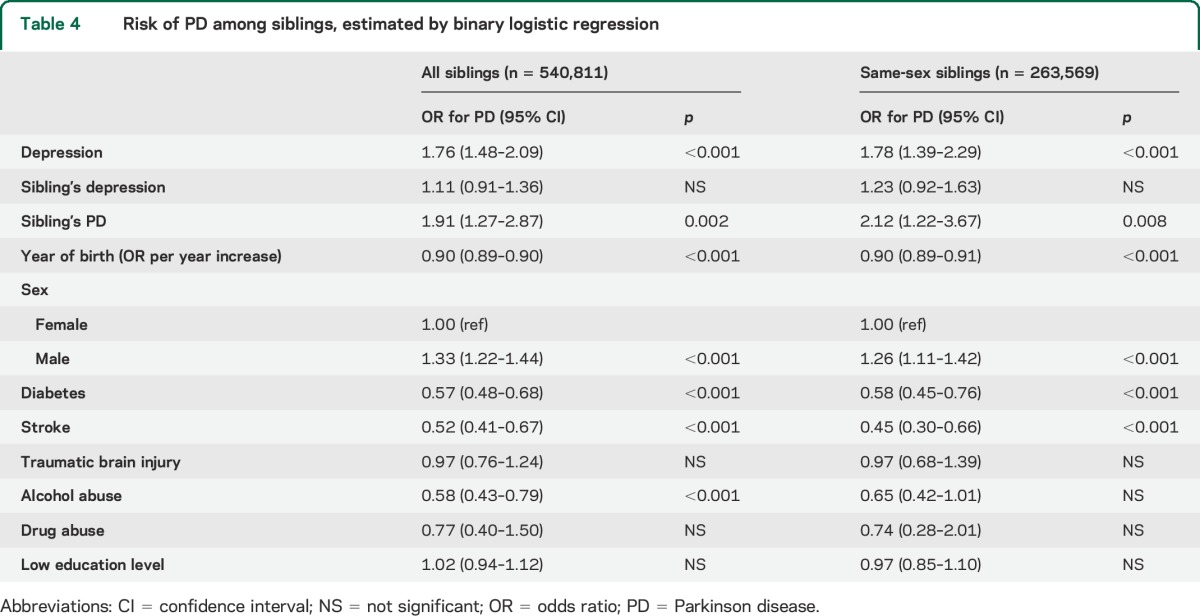

In the sibling cohort, which consisted of 540,811 sibling pairs, 20,413 (3.8%) index persons were diagnosed with depression (with no prior diagnosis of PD) and 2,302 (0.4%) were diagnosed with PD; 21,403 (4.0%) index persons had siblings diagnosed with depression and 2,435 (0.5%) had siblings diagnosed with PD (table 1). PD was more common among participants diagnosed with depression (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.48–2.09) and in those with siblings diagnosed with PD (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.27–2.87), whereas siblings' depression was not associated with the risk of PD in the index persons (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.91–1.36). Analysis of only same-sex sibling pairs did not substantially change these results (table 4).

Table 4.

Risk of PD among siblings, estimated by binary logistic regression

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study is a distinct relationship between depression and a subsequently increased risk of PD; this association weakened over time, but remained significant during a follow-up period of more than 2 decades. The time-dependent effect, dose-response relationship to severity and recurrence of depression, and absence of evidence for familial confounding all support a direct association between the 2 diagnoses. Taken together, our findings indicate that depression is an early prodromal symptom of PD or a causal risk factor.

Our results are consistent with a growing body of evidence for the relationship between depression and subsequent PD,4–14 and the present study contributes to this evidence with strong, prospective, long-term data. One recent study13 reported a similar, significant association over a 10-year period, but investigations covering more than a decade of follow-up are rare and results have been inconclusive.6,12,14 One study based on retrospective data for a period of >15 years12 found a significantly increased risk of PD among participants with depression for all time intervals investigated. In contrast, associations found in smaller studies6,14 lost significance at lag times of 2 and 5 years, respectively, after the onset of depression. The substantial statistical power of the present study is a likely reason for the observation of significant differences in time intervals, whereas most previous studies have documented only trends. The persistence of the association during the entire follow-up period highlights the importance of investigating potential risk markers for PD from a long-term perspective, and may be a finding of significance in clinical practice; the increased risk of PD among patients with a long history of depression should be considered when other symptoms attributable to PD arise.

Several mechanisms could explain the association between depression and subsequent PD. First, depression and/or drugs used as antidepressive treatment could increase the risk of PD. In the present study, the dose-response relationship between severity and recurrence of depression and subsequent risk of PD indicates a direct relationship, but the prodromal timeline of PD is still indefinite and depression could not be verified to actually precede the onset of PD pathology. Thus, a second plausible explanation is that depression is an early symptom appearing in the prodromal phase of PD, which may begin decades before clinical onset,19 but reliable evaluations of temporal aspects have been limited because of a lack of continuously collected prospective data. The tendency of persistence or recurrence of depressive symptoms arising from a progressive degenerative disease is reasonable and could explain the dose-response associations between severity and recurrence of depression and risk of PD in the present study. Similarly, a recent study13 reported that difficult-to-treat depression, defined by a change in medication, was a risk marker for PD. Moreover, the time-varying strength of the association between depression and PD is probably best explained by this hypothesis; subtle deficits may be present for decades but are not necessarily overt until shortly before the onset of motor symptoms.

A third hypothesis is that depression and PD are independent of each other, but share genetic and/or environmental etiologic factors. Increased prevalence of mental illness has been reported among relatives of patients with PD,15 supporting this theory. If the 2 diseases were independent of one another, but caused by the same genetic or early environmental factors, we would expect coaggregation of both diagnoses within sibling pairs. One previous study involving siblings produced no significant finding.14 Similarly, despite a considerably larger dataset, the present study provided no evidence of familial confounding. The association was also not explained by interaction from comorbid conditions in the present cohort, further supporting the independence of the association between depression and subsequent PD.

The main strengths of the present study are the large, population-based dataset, which provided exceptional statistical power over a long follow-up period, and the prospective registration of diagnoses, avoiding recall bias and providing reliable data for temporal analyses. The availability of information for family linkage allowed us to assess confounding by shared susceptibility, which has rarely been investigated before and also avoided recall bias.

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, diagnoses obtained from registries were not clinically confirmed for the study. However, the accuracy of diagnoses listed in Swedish registries has been found to be high.21 All diagnoses included in the study were registered in the course of specialist health care, and cases of depression and PD treated in primary health care contexts, probably milder cases, may have been missed. Neither could diagnoses before the nationwide registration began be captured. Because the study was restricted to depression, and did not include other psychiatric diagnoses associated with PD and depression, such as anxiety,6,14,31–33 bipolar disorders,31 and schizophrenia,31 patients with depressive symptoms secondary to other psychiatric disorders may have been missed. However, it should be noted that missed diagnoses or incorrect diagnoses would likely widen the standard errors and attenuate the associations between depression and PD toward zero.34 Second, we did not have access to information about drugs prescribed, preventing evaluation of the potential role of substances used in antidepressive treatment as risk factors for PD. Besides antidepressives and mood stabilizers, antipsychotic drugs may also be used to treat depression,35,36 and there are indications that drug-induced parkinsonism may be a risk factor for later development of PD.37 However, many factors may affect the choice of treatment for depression, meaning that reliable examination of whether different treatment options affect the risk of PD was beyond the limits of this observational study. Third, no data on smoking habit, a factor strongly associated with the risk of PD, were available. However, the possible interaction between smoking and depression in the context of PD has previously been investigated, with no significant finding.12

Our findings suggest a direct association between depression and subsequent PD, supported by a time-dependent hazard ratio, a dose-response pattern for recurrent depression, and a lack of evidence for coaggregation among siblings. Given that the association was significant over more than 2 decades of follow-up, depression may be a very early prodromal symptom of or a causal risk factor for PD.

GLOSSARY

CI

confidence interval

ICD

International Classification of Diseases

NCC

nested case-control

NPR

National Patient Register

OR

odds ratio

PD

Parkinson disease

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.N. and A.N. conceived the idea for the study. H.G. compiled and analyzed the data, and made initial drafts of tables and figures with input from P.N. H.G. led the writing of the manuscript with contribution from all other authors.

STUDY FUNDING

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council. The funding bodies did not have a role in the design, writing, or decision to publish the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lieberman A. Depression in Parkinson's disease: a review. Acta Neurol Scand 2006;113:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, Aarsland D, Leentjens AF. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frisina PG, Borod JC, Foldi NS, Tenenbaum HR. Depression in Parkinson's disease: health risks, etiology, and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2008;4:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishihara L, Brayne C. A systematic review of depression and mental illness preceding Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2006;113:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor CA, Saint-Hilaire MH, Cupples LA, et al. Environmental, medical, and family history risk factors for Parkinson's disease: a New England-based case control study. Am J Med Genet 1999;88:742–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiba M, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders preceding Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Mov Disord 2000;15:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuurman AG, van den Akker M, Ensinck KT, et al. Increased risk of Parkinson's disease after depression: a retrospective cohort study. Neurology 2002;58:1501–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leentjens AF, Van den Akker M, Metsemakers JF, Lousberg R, Verhey FR. Higher incidence of depression preceding the onset of Parkinson's disease: a register study. Mov Disord 2003;18:414–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson FM, Kessing LV, Bolwig TG. Increased risk of developing Parkinson's disease for patients with major affective disorder: a register study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Sundquist J, Hwang H, Sundquist K. Impact of psychiatric disorders on Parkinson's disease: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. J Neurol 2008;255:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso A, Rodriguez LA, Logroscino G, Hernan MA. Use of antidepressants and the risk of Parkinson's disease: a prospective study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:671–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang F, Xu Q, Park Y, et al. Depression and the subsequent risk of Parkinson's disease in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Mov Disord 2010;25:1157–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen CC, Tsai SJ, Perng CL, Kuo BI, Yang AC. Risk of Parkinson disease after depression: a nationwide population-based study. Neurology 2013;81:1538–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob EL, Gatto NM, Thompson A, Bordelon Y, Ritz B. Occurrence of depression and anxiety prior to Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:576–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arabia G, Grossardt BR, Geda YE, et al. Increased risk of depressive and anxiety disorders in relatives of patients with Parkinson disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirdefeldt K, Adami HO, Cole P, Trichopoulos D, Mandel J. Epidemiology and etiology of Parkinson's disease: a review of the evidence. Eur J Epidemiol 2011;26(suppl 1):S1–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 1991;114:2283–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marek K, Jennings D. Can we image premotor Parkinson disease? Neurology 2009;72(7 suppl):S21–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkes CH. The prodromal phase of sporadic Parkinson's disease: does it exist and if so how long is it? Mov Disord 2008;23:1799–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. The National Patient Register. Available at: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/patientregistret/inenglish. Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 21.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish National Inpatient Register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Dödsorsaksregistret [in Swedish]. Available at: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/dodsorsaksregistret. Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 23.Statistics Sweden. Multi-Generation Register 2010: A Description of Contents and Quality. Örebro: Statistics Sweden; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS. Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke 2005;36:1330–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seel RT, Kreutzer JS, Rosenthal M, Hammond FM, Corrigan JD, Black K. Depression after traumatic brain injury: a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model Systems multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant BF. Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. J Subst Abuse 1995;7:481–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995;39:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend 2001;63:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med 2002;21:2175–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HL, Lin HC, Chen YH. Psychiatric diseases predated the occurrence of Parkinson disease: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 2014;24:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weisskopf MG, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Kawachi I, Ascherio A. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2003;18:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bower JH, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, et al. Anxious personality predicts an increased risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:2105–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA. Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. BMJ 2010;340:c2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bschor T, Bauer M, Adli M. Chronic and treatment resistant depression: diagnosis and stepwise therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:766–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DP. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chabolla DR, Maraganore DM, Ahlskog JE, O'Brien PC, Rocca WA. Drug-induced parkinsonism as a risk factor for Parkinson's disease: a historical cohort study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73:724–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]