Shared Pluripotency Programs Suggest Derivation of Vertebrate Neural Crest from Blastula Cells (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Nov 19.

Published in final edited form as: Science. 2015 Apr 30;348(6241):1332–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3655

Abstract

Neural Crest cells, unique to vertebrates, are derived from the ectoderm but also generate mesodermal cell types. This broad developmental potential persists past the time when most ectoderm-derived cells have become lineage restricted. The ability of neural crest to contribute mesodermal derivatives to the bauplan has raised questions about how this apparent gain in developmental potential is achieved. Here we describe shared molecular underpinnings of potency in neural crest and blastula cells. We show that in Xenopus, key neural crest regulatory factors are also expressed in blastula animal pole cells and promote pluripotency in both cell types. We suggest that neural crest cells may have evolved as a consequence of a subset of blastula animal pole cells retaining activity of the regulatory network underlying pluripotency.

Keywords: Neural crest, Neural Plate Border, Xenopus, stem cell, pluripotency, Snail, Sox5

Embryogenesis initiates with a totipotent fertilized egg cell, and subsequent development is characterized by progressive restrictions in cellular potential. At blastula stages, when the three primary germ layers are forming, chordate embryos still possess populations of pluripotent cells that are capable of differentiating into all somatic cell types. In mammals these are inner cell mass cells, whereas in Xenopus these cells are the deep/inner cells of the blastula roof, also termed animal pole cells (1). The pluripotency of blastula cells is transient; as embryogenesis proceeds into gastrulation, their potential becomes rapidly restricted into one of three cell types: ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. In all vertebrate species, a population of stem cell-like progenitors, called neural crest cells, represents an exception to this loss of potential. These cells arise from ectoderm positioned at the neural plate border, and yet they will ultimately differentiate into both mesodermal and ectodermal cell types.

Neural crest cells represent a major vertebrate innovation, collectively giving rise to many of the features that distinguish vertebrates from non-vertebrate chordates, including the jaws and skull, most of the peripheral nervous system, and the endocrine cells of the adrenal medulla. Because neural crest, despite its ectodermal origins, forms numerous cell types considered mesodermal, including bone and cartilage, it has been likened to a fourth germ layer that renders vertebrates quadroblastic, and endows them with the potential to form a diversity of new cell types (2).

Much effort has been directed toward determining the developmental mechanisms by which a classic embryonic induction leads to the formation of the neural crest; cells that seemingly possess greater developmental potential than those from which they were derived embryologically or evolutionarily. Under current models these cells appear to defy the paradigm of progressive restriction in potential, and thus far no mechanism has been found to explain their apparent gain in potential. An alternative, more parsimonious, model for the origins of neural crest cells might be that they selectively retain the regulatory circuitry responsible for the pluripotency of their blastula precursors; a selective retention of earlier features. This model is supported by a shared requirement for Myc protein, and its transcriptional target Id3, in both neural crest cell genesis and ES cell pluripotency (3-6). We recently found that another neural crest regulatory transcription factor, Sox5, is initially expressed in blastula cells where it functions as a BMP R-Smad co-factor (7), providing an additional link between neural crest cells and pluripotent blastula cells. Based on these observations, we decided to systematically test the alternative model in Xenopus.

Neural Crest Shares Regulatory Circuitry with Pluripotent Blastula Cells

In mammals, Pou5F1 (Oct4), Sox2 and Nanog, constitute a core pluripotency network essential for maintaining the uncommitted state of blastula cells (8-13). In Xenopus, the Pou5F1 factors expressed in ectoderm are Pou5F3.1 (Oct91), Pou5F3.2 (Oct25) and Pou5F3.3 (Oct60) (14, 15). The functional role of Nanog in Xenopus is assumed by Ventx factors (Vent1/2) (16). These factors, along with Sox2, and the closely related Sox3, are expressed in blastula cells (17, Fig. 1A). We wondered if other neural crest regulatory factors besides Myc, Id3 and Sox5 were co-expressed with the core pluripotency network in Xenopus blastula cells. We found that Id3, TF-AP2, Ets1, FoxD3 and Snail1 were co-expressed with the core pluripotency factors (Fig. 1B). FoxD3 and Snail1 are also expressed in murine ES cells (18, 19), providing further molecular links between neural crest factors and pluripotency. While these neural crest and pluripotency factors exhibited broad expression during blastula stages, their expression became progressively restricted as lineage determination progressed, with several genes, including Oct60, Sox3, Vent2, Ets1, Zic1, Pax3, and Snail1, showing enhanced expression at the neural plate border by late gastrula stages (Fig. S1, A and B). We found Vent2 was co-expressed with Snail2 at late gastrula/neurula stages when neural crest cells retain their full developmental potential, but was down-regulated as these cells begin to migrate and lose multipotency (Fig. S1C).

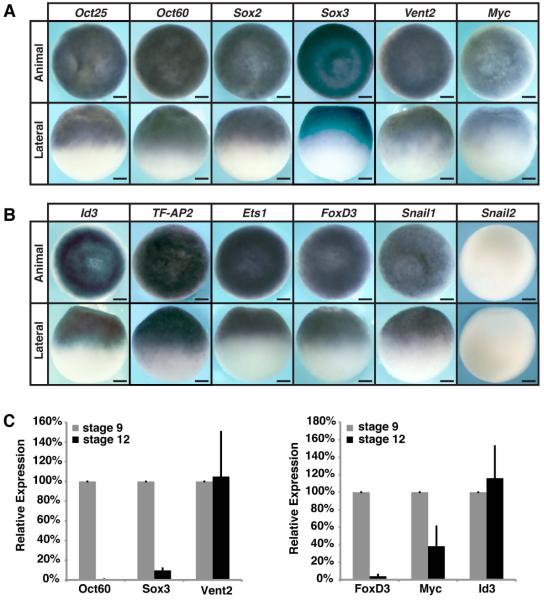

Figure 1.

Neural crest cells and pluripotent blastula cells share a common regulatory circuitry. (A-B) In situ hybridization of wildtype blastula (stage 9) Xenopus embryos examining expression of genes associated with pluripotency (A) or neural crest formation (B). Scale bars, 250 µM. (C) qRT-PCR of wildtype ectodermal explants examining relative expression of pluripotency genes and neural crest genes over developmental time.

Explanted blastula animal pole cells retain full developmental potential until the onset of gastrulation, when they lose competence to form mesoderm and endoderm (20, 21). We thus examined whether expression of regulatory factors present in pluripotent blastula cells is lost when explants age and their developmental potential becomes restricted. Oct60, Sox3, FoxD3, and Myc expression was high in blastula-stage explants but reduced by late gastrula stages, correlating with loss of potential (Fig. 1C). Not all potency factors were down-regulated as these cells lost plasticity; expression of Vent2 and Id3 was unchanged as explants aged from blastula to gastrula stages (Fig. 1C). This suggests a concentration-dependent signature of regulatory factors may be essential to retaining broad developmental potential and preventing lineage restriction, consistent with findings in mouse that specific threshold concentrations of Oct4 (50-150% of endogenous levels) support pluripotency, while levels outside this range lead to differentiation (9, 22).

Neural Crest Factors Are Required for Pluripotency in Blastula Cells

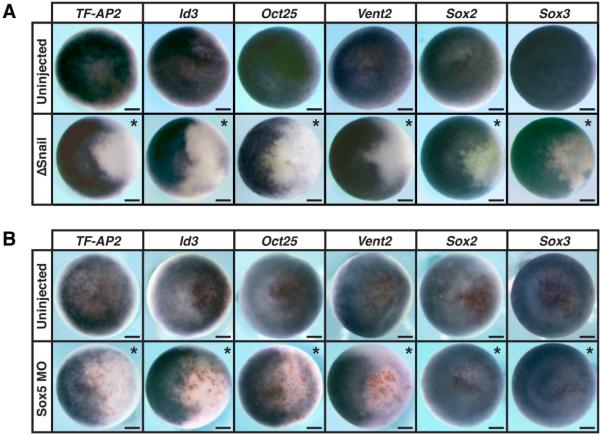

Given that neural crest potency factors are co-expressed with core pluripotency factors in blastula cells, we asked if they were required to maintain expression of these pluripotency factors. Blocking Snail1 function in the animal pole of blastula embryos cells led to loss of expression of factors linked to the neural crest state, such as TF-AP2 and Id3 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). Expression of Oct/Sox/Vent network components was also lost (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). We obtained similar results when Sox5 function was blocked in animal pole cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3B). Thus, neural crest regulatory factors are not merely expressed in pluripotent blastula cells, but also function there to maintain expression of core pluripotency factors.

Figure 2.

Neural crest regulatory factors are required for the expression of blastula pluripotency factors. (A-B) In situ hybridization of embryos injected with ΔSnail mRNA (A) or Sox5 MO (B). Embryos were collected at blastula stages (stage 9) and examined for expression of genes associated with pluripotency/neural crest formation. Asterisk denotes injected side with β-gal staining (red) serving as a lineage tracer. Scale bars, 250 µM.

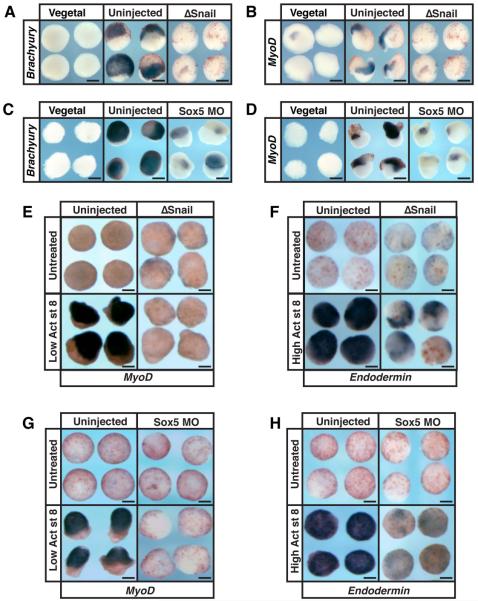

The developmental plasticity of amphibian animal pole cells was first demonstrated by Peter Nieuwkoop, whose recombinant assay drove current understanding of mesendoderm formation (23, Fig. S1D). Since we found that neural crest factors such as Snail1 are required for maintaining expression of factors linked to pluripotency, we hypothesized that cells lacking Snail1 function would lack competence to respond to endogenous inducing signals. To test this, animal pole explants from control blastulae, or blastulae in which Snail1 function had been blocked, were recombined with vegetal tissue from sibling embryos. Control recombinants robustly expressed mesodermal markers Brachyury and MyoD, whereas animal pole cells blocked for Snail1 function showed dramatically diminished responsiveness (Fig. 3, A and B and Fig. S3, C and D). Similar results were observed with animal pole cells depleted of Sox5 (Fig. 3, C and D and Fig. S3, C and D). As with conjugation to vegetal tissue, treatment of pluripotent blastula cells with low/moderate doses of activin instructs them to form mesoderm, and this responsiveness is also lost in cells depleted of Snail or Sox5 function (Fig. S1E, Fig. 3, E and G, Fig. S2, A and C and Fig. S3, E and F).

Figure 3.

Neural crest regulatory factors are required for pluripotency of blastula cells. (A-D) Nieuwkoop recombinant assay examining expression of Brachyury (A,C) and MyoD (B,D) after depleting Snail1 (A,B) or Sox5 function (C,D). Recombinants were harvested at gastrulation stages for Brachyury expression (stage 11.5) or early neurula stages (stage 13/14) for MyoD expression. (E-H) Ectodermal explant assay examining expression of MyoD (E,G) and Endodermin (F,H). Explants were injected with ΔSnail mRNA (E,F) or Sox5 MO (G,H) and cultured with or without activin until early neurula stages for MyoD expression (stage 13/14) and midgastrula stages (stage 11.5) for Endodermin expression. Scale bars, 250 µM.

Since Snail factors have endogenous roles in mesoderm formation, a more demanding test of their contributions to pluripotency was to ask if blastula cells lacking Snail1 function consequently lose their capacity to form endoderm. Blastula explants adopt endodermal fates in response to high activin concentrations, expressing endoderm-specific genes such as Endodermin and Sox17. However, blastula explants depleted of Snail function could no longer form endoderm (Fig. 3F, Fig. S2B and Fig. S3, G and H). Snail proteins are neither expressed in, nor function in, endoderm endogenously, thus loss of activin-mediated endoderm induction likely reflects a general lack of competence of Snail depleted animal pole cells to respond to endoderm-inducing signals. Similar results were found when Sox5 was depleted from blastula cells (Fig. 3H and Fig. S2D and Fig. S3, G and H).

Reprogrammed Neural Crest Can Form Endoderm

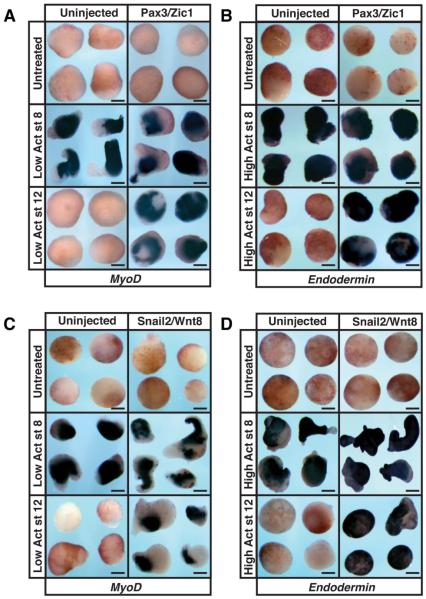

Given that neural crest potency factors are expressed in pluripotent blastula cells and required for expression of core pluripotency factors, we further explored the link between the neural crest state and the pluripotent blastula state. Specifically, we asked if establishing a neural crest state is sufficient to confer pluripotency on, or prevent loss of pluripotency in, descendants of blastula animal pole cells. Animal pole cells explanted at blastula stages are initially competent to give rise to all somatic cell types, but lose pluripotency by gastrula stages. Established protocols exist for converting blastula animal pole explants to a neural plate border or neural crest state. Combined expression of Pax3 and Zic1 efficiently converts explants to neural plate border (24-26) whereas Snail2 together with Wnt signaling is sufficient to establish a neural crest state (27, 28). We therefore asked if converting these explants to a neural plate border or neural crest state would be sufficient to prevent loss of competence and extend the pluripotency of these cells (Fig. S1F).

As predicted, explants treated at blastula stages with mesoderm-inducing concentrations of activin robustly expressed the mesoderm-specific MyoD gene, but if explants were aged to gastrula stages before treatment they were unable to form mesoderm (Fig. 4A). By contrast, explants converted to a neural plate border state retained their potency and formed mesoderm in response to either early or late activin treatment (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4A). We also tested whether this change in plasticity extended to endoderm formation. When blastula-derived cells were treated with endoderm-inducing doses of activin, identical results were achieved (Fig. 4B). Explants treated with high activin at blastula states expressed the endodermal markers Endodermin and Sox17 but were unable to do so when treated at gastrula stages (Fig. 4B, Fig. S2E). By contrast, Pax3/Zic1 programmed explants retain the ability to form endoderm even when treated at gastrula stages (Fig. 4B, Fig. S2E and Fig. S4, C and E). Similarly, blastula-derived cells programmed to a neural crest state with Snail2/Wnt8 retain competence to form mesoderm and endoderm through gastrula stages (Fig. 4, C and D, and Fig. S2F and Fig. S4, B, D and F). The ability of neural plate border/neural crest factors to prevent loss of pluripotency in animal pole derived cells, combined with the requirement of these factors for the normal plasticity of these cells at blastula stages, suggests a close link between the molecular networks controlling the potency of neural crest and blastula cells.

Figure 4.

Establishing a neural crest state prevents loss of potency in blastula-derived cells. (A-D) Ectodermal explant assay examining expression of MyoD (A,C) or Endodermin (B,D) in embryos that were injected with Pax3-GR/Zic1-GR mRNA (A,B) or Snail2/Wnt8 mRNA (C,D). Explants were treated with activin at either stage 8 or 12 and cultured until late neurula stages (stage 18). Scale bars, 250 µM.

Endogenous Neural Crest can form Endoderm

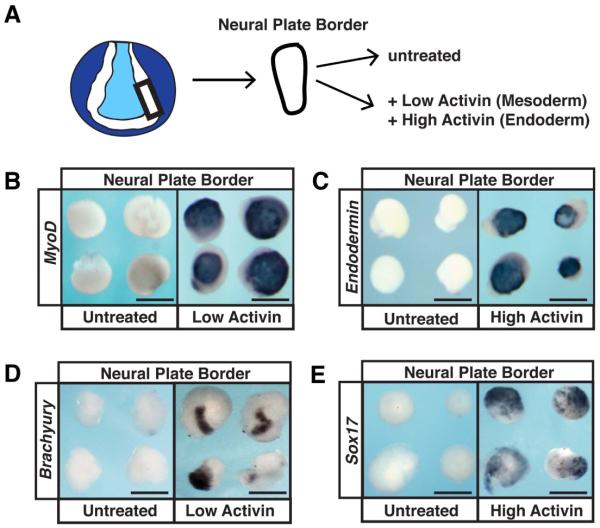

If such a link exists, one prediction is that cells isolated from the neural plate border region of an intact neurula-stage embryo should also exhibit broad developmental potential, including the capacity to form both mesoderm and endoderm. This capacity should exist even though there is currently no evidence that neural plate border-derived cells form endoderm during normal development. To test this prediction we isolated neural plate border cells from neurula stage embryos, and cultured them in vitro. As expected, when these cells were cultured without inducers they did not express the mesodermal markers MyoD or Brachyury, or the endodermal markers Endodermin or Sox17 (Fig. 5, A-E). However, treatment of neural plate border explants with concentrations of activin sufficient to induce mesoderm or endoderm in pluripotent blastula cells elicited strong expression of all of these genes (Fig. 5, A-E, Fig. S2G and Fig. S4, G-J). These findings demonstrate that endogenous neural crest cells possess a much greater degree of potency/plasticity than has previously been appreciated, including an unexpected capacity for endoderm formation.

Figure 5.

Neural crest cells possess the capacity for endoderm formation. (A) Schematic representation of neural plate border/neural crest isolation. Neural folds are dissected at early neurula stages (stage 14/15) and cultured with or without activin until late neurula stages (stage 18). (B-E) In situ hybridization examining expression of MyoD (B), Endodermin (C), Brachyury (D), and Sox17 (E) in neural plate border/neural crest tissue treated with or without activin. Scale bars, 250 µM.

Discussion

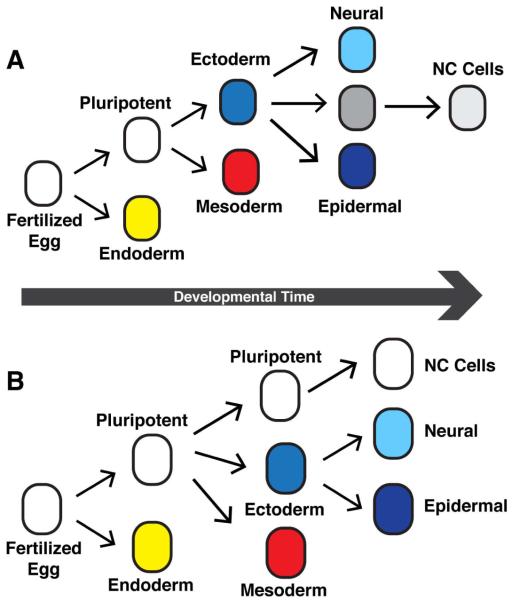

Longstanding models for neural crest formation posit that inductive interactions endow these cells with greater developmental potential than the cells they were derived from, developmentally or evolutionarily (25-28, Fig 6A). This classic view implies a unique reversal of trajectory in Waddington’s landscape of progressive restriction of developmental potential (29). Based upon our findings reported here, we suggest instead a revised model in which neural crest cells are an example of cellular neoteny (30). Select cells with the pluripotent potential characteristic of the blastula state persist to neurula stages where they can be induced to form the highly diverse lineages that derive from the neural crest (Fig 6B). This retention of pluripotency long after other cells have become fate restricted has endowed the neural crest with the capacity to contribute the novel attributes characteristic of vertebrates to the simple chordate bauplan. Mechanistically, we propose that neural crest cells arose as a consequence of their retention of all or part of a regulatory network that controls pluripotency in the blastula cells from which they were derived. Their previously unrecognized capacity for endoderm formation raises the intriguing possibility that they might contribute to endodermal cell types endogenously, and this will be an important area of future investigation with implications for regenerative medicine.

Figure 6.

(A) Historic model of neural crest induction in which neural crest cells were believed to gain potential relative to predecessor cells. (B) Proposed model for the generation of neural crest cells via retention of pluripotency characteristics of earlier blastula cells.

The new model for formation of neural crest cells proposed here provides a framework for future studies in basal chordates to probe the earliest evolutionary origins of these cells. Ascidians, for example, possess a cell lineage that arises from the neural plate border and expresses genes such as Snail, Id, FoxD and Ap2, all of which we find shared between pluripotent blastula cells and neural crest. This a9.49 lineage has been proposed to have at least rudimentary homology to vertebrate neural crest (31). Investigating shared and divergent aspects of pluripotency network components in these and other protochordate and basal vertebrate models should therefore shed light on when and how pluripotency was retained in cells that become neural crest, and thus provide insight into the evolutionary origins of vertebrates.

Supplementary Material

1

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Nguyen for technical assistance, S. Sokol for providing activin, and R. Carthew and X. Wang for helpful discussions. K.N. was supported by F31DE021922 and T32CA009560-24. This work was supported by R01GM114058 to C.L. Supplement contains additional data.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

Materials and Methods

Figures S1 to S4

References

- 1.Furue M, Asashima M. In: Handbook of Stem Cells. 46. Lanza R, et al., editors. Vol. 1. Elsevier; Burlington, San Diego, London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall BK. The Neural Crest in Development and Evolution. 1 Springer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Light W, Vernon AE, Lasorella A, Iavarone A, LaBonne C. Xenopus Id3 is required downstream of Myc for the formation of multipotent neural crest progenitor cells. Development. 2005;132:1831–1841. doi: 10.1242/dev.01734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellmeyer A, Krase J, Lindgren J, LaBonne C. The protooncogene c-myc is an essential regulator of neural crest formation in xenopus. Dev Cell. 2003;4:827–839. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright P, et al. LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Mycdependent mechanism. Development. 2005;132:885–896. doi: 10.1242/dev.01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ying Q-L, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordin K, LaBonne C. Sox5 Is a DNA-Binding Cofactor for BMP R-Smads that Directs Target Specificity during Patterning of the Early Ectoderm. Developmental Cell. 2014;31:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols J, et al. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niwa H, Smith AG, Miyazaki J-I. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avilion AA, et al. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes & Development. 2003;17:126–140. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, Nichols J, Lee S. Functional Expression Cloning of Nanog, a Pluripotency Sustaining Factor in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsui K, et al. The Homeoprotein Nanog Is Required for Maintenance of Pluripotency in Mouse Epiblast and ES Cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young RA. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell. 2011;144:940–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankenberg SR, et al. The POU-er of gene nomenclature. Development. 2014;141:2921–2923. doi: 10.1242/dev.108407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison GM, Brickman JM. Conserved roles for Oct4 homologues in maintaining multipotency during early vertebrate development. Development. 2006;133:2011–2022. doi: 10.1242/dev.02362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scerbo P, et al. Ventx Factors Function as Nanog-Like Guardians of Developmental Potential in Xenopus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers CD, Archer TC, Cunningham DD, Grammer TC, Casey EMS. Sox3 expression is maintained by FGF signaling and restricted to the neural plate by Vent proteins in the Xenopus embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;313:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Labosky PA. Regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency by Foxd3. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2475–2484. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Y, et al. Snail1-dependent control of embryonic stem cell pluripotency and lineage commitment. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3070. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones EA, Woodland HR. The development of animal cap cells in Xenopus: a measure of the start of animal cap competence to form mesoderm. Development. 1987;101:557–563. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grainger RM, Gurdon JB. Loss of competence in amphibian induction can take place in single nondividing cells. PNAS. 1989;86:1900–-1904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers I, Tomlinson SR. The transcriptional foundation of pluripotency. Development. 2009;136:2311–2322. doi: 10.1242/dev.024398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieuwkoop PD. The Formation of the Mesoderm in Urodelean Amphibians. W. Roux' Archivf. Entwicklungsmechanik. 1969;163:298–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00577017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato T. Neural crest determination by co-activation of Pax3 and Zic1 genes in Xenopus ectoderm. Development. 2005;132:2355–2363. doi: 10.1242/dev.01823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong C. J. Saint-Jeannet, The Activity of Pax3 and Zic1 Regulates Three Distinct Cell Fates at the Neural Plate Border. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:2192–2202. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monsoro-Burq A-H, Wang E, Harland R. Msx1 and Pax3 cooperate to mediate FGF8 and WNT signals during Xenopus neural crest induction. Dev Cell. 2005;8:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaBonne C, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest induction in Xenopus: evidence for a two-signal model. Development. 1998;125:2403–2414. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.13.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor K, LaBonne C. Modulating the activity of neural crest regulatory factors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waddington CH. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature. 1942;3811:563–565. doi: 10.1038/1831654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson D. Cellular ‘neoteny’: A possible developmental basis for chromaffin cell plasticity. Trends in Genetics. 1989;5:174–184. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abitua PB, Wagner E, Navarrete IA, Levine M. Identification of a rudimentary neural crest in a non-vertebrate chordate. Nature. 2012;492:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1