Learning from Marketing: Rapid Development of Medication Messages that Engage Patients (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Dec 20.

Published in final edited form as: Patient Educ Couns. 2015 Mar 14;98(8):1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.02.016

Abstract

Objective

To adapt marketing approaches in a health services environment.

Methods

Researchers and advertising professionals partnered in developing advertising-style messages designed to activate patients pre-identified as having chronic kidney disease to ask providers about recommended medications. We assessed feasibility of the development process by evaluating partnership structure, costs, and timeframe. We tested messages with patients and providers using preliminary surveys to refine initial messages and subsequent focus groups to identify the most persuasive ones.

Results

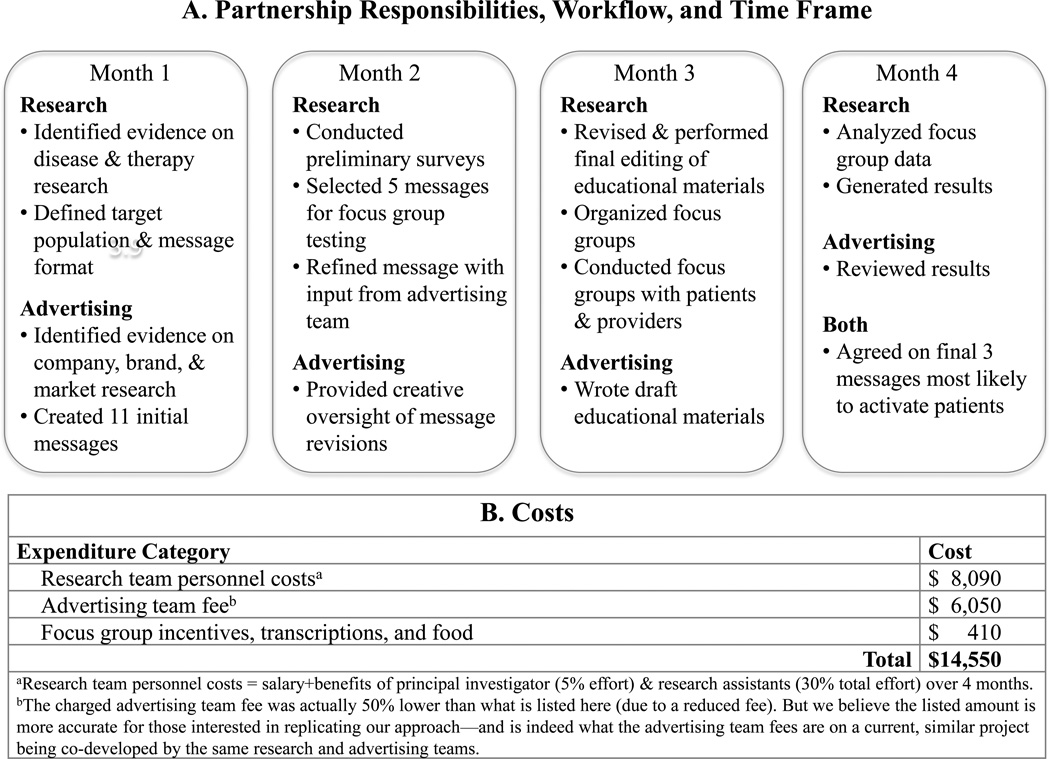

The partnership achieved an efficient structure, $14,550 total costs, and 4-month timeframe. The advertising team developed 11 initial messages. The research team conducted surveys and focus groups with a total of 13 patients and 8 providers to identify three messages as most activating. Focus group themes suggested the general approach of using advertising-style messages was acceptable if it supported patient-provider relationships and had a credible evidence base. Individual messages were more motivating if they elicited personal identification with imagery, particular emotions, active patient role, and message clarity.

Conclusion

We demonstrated feasibility of a research-advertising partnership and acceptability and likely impact of advertising-style messages on patient medication-seeking behavior.

Practice Implications

Healthcare systems may want to replicate our adaptation of marketing approaches to patients with chronic conditions.

Keywords: advertising, patient activation, health communication

1. Introduction

Chronic conditions account for the majority of preventable adult morbidity and mortality [1]. Effective use of medications may delay or halt disease progression, yet they are frequently underutilized. Chronic kidney disease—which affects 15% of U.S. adults [1]—is representative of this sizable missed opportunity [2]. Nearly half of persons with CKD having stage 3 (“moderate”) disease, a critical juncture during which patients are at increased risk for progression to end-stage disease (i.e., need for dialysis or transplantation) [1, 3] but also have the potential to benefit from secondary prevention [4–6]. Use of recommended, inexpensive medications is a proven strategy of preventing or delaying CKD progression [3, 7–11]. Yet low-cost generic medications for CKD go largely under-prescribed [7, 9–11].

Practice guidelines and patient education campaigns generally have failed to increase initiation of indicated CKD medications [7]. Even among high-risk patients with stages 3–4 CKD and concurrent diabetes mellitus and hypertension, only 60% are taking an inhibitor of the renin-angiotensin system (angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB))—despite evidence that these medications help protect the kidneys from further deterioration [12]. In the current study, we focus on ACE inhibitors because they are generally well-tolerated and inexpensive, and numerous guidelines endorse their use [7, 13].

Interventions that boost patient activation for self-care of chronic conditions improve outcomes [14, 15]. Priming patients with specific materials prior to clinic visits increases discussion with providers and the likelihood that specific medications will be prescribed [14, 16]. Nevertheless, patient activation efforts are only as effective as their ability to capture attention and overcome behavioral barriers that hinder engagement [17, 18]. Behavioral barriers are both cognitive (knowledge-based, “rational”) and affective (emotions-based) [19]. Examples of the latter include avoidance, denial, and uncertainty [5, 20–22]. Patients are more likely to overcome behavioral barriers if they are explicitly addressed [23]. Clinical and public health interventions often have focused solely on overcoming cognitive, but not affective, barriers [24].

Marketing and social psychology approaches have successfully overcome affective barriers by directly targeting emotions [14, 25, 26]. A majority of customers choose products based on emotions [27]. Pharmaceutical companies have leveraged this propensity in direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising: 67% of DTC advertisements appeal to emotions rather than knowledge [28]. Their impact on patient medication requests and initiation is well documented. For example, providers report that their patients regularly inquire about medications they have seen in advertisements [29]. Eight percent of consumers who see a specific medication advertised then request it from their physicians, and 73% of those physicians prescribe it [30].

Healthcare systems have a notable benefit not available to pharmaceutical companies—access to patient health records. They can search these to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from medical interventions and yet are not receiving them. Rather than needing to launch a mass marketing campaign to reach just the few patients for whom the intervention is relevant, they have the potential to target patients selectively. But healthcare systems face considerable challenges when contemplating development of marketing materials. They may have limited time, money, or expertise [31]. Furthermore, medication marketing in the U.S. is dominated by pharmaceutical companies whose goals are increased market penetration and profit. In contrast, medication promotion by healthcare systems must first and foremost support the therapeutic alliance between patients and providers. However, patients or providers may conflate DTC-style messages sent by health systems with pharmaceutical marketing and become concerned that health systems are pursuing secondary gain rather than patient wellbeing. In short, healthcare systems are well positioned to perform medication marketing but to do so require resources, expertise, and assurances that the approach is likely to be effective and will not undermine the patient-provider relationship.

We sought to develop digital marketing materials—“advertising-style messages”—capable of overcoming emotional barriers preventing adoption of recommended medications by patients with chronic conditions, in this case ACE inhibitors by patients with moderate CKD. We predicted that our health services research team could partner successfully with medical advertising professionals to produce advertising-style messages that would be both acceptable as a general approach and individually persuasive. In summary, our goals were to assess (a) the feasibility of the partnered development process and (b) the acceptability and potential impact of advertising-style messages designed to prompt patient activation and patient-provider communication regarding initiation of recommended medications.

2. Methods

We describe below our partnership, development process, and how we assessed them for feasibility and the messages for acceptability and impact.

2.1. Feasibility Issues

Our health services researcher team (“research team”) partnered with two medical advertising professionals (“advertising team”). The partnership structure was designed to bring together complementary areas of expertise but minimize overlap of responsibilities and workflow. The research team—one primary care internal medicine physician (principal investigator (PI)) and two research assistants (RAs) pursuing their masters’ degrees in public health—encompassed expertise in clinical care, chronic disease management, health communication, patient activation/behavior change, and mixed methods research. One RA had expertise in graphic design. The advertising team members were selected for experience in creative direction of pharmaceutical marketing campaigns. Both work with a non-profit established to inform medical decision-making with balanced information (www.rxbalance.org). Once partnered, research and advertising teams co-designed project responsibilities and workflow.

The research team assessed the feasibility of the partnership for future replication by others according to its structure (necessary expertise, responsibilities, workflow), costs (for materials, fees, and personnel time), and timeframe. It collected the cost and timeframe data to guide health systems potentially interested in budgeting for and replicating the partnered development process rather than as something it is arguing should—or even can—be linked to clinical outcomes data, which are not available in the current study.

2.2. Defining Campaign Characteristics

The research team defined characteristics essential to any advertising campaign—first, the target audience, patients with moderate CKD. The ideal target patient population for an intervention promoting medication initiation is one with a chronic condition that can be defined with specificity, has a strong evidence base favoring medication use, and yet has persistent underutilization. Second, the anticipated context of the messages was as part of a larger, direct-to-patient campaign, within which they would be combined with each other and educational materials. Third, the content objective of each message was to overcome at least one emotional barrier to patient activation. Finally, the team wanted the messages to be sent electronically but to retain flexibility in the exact mechanism of delivery (e.g., via webpage, smartphone, or email). Thus, it chose a message format that could be applied across a variety of digital platforms—a primarily pictorial one containing static visual components (“imagery”) combined with short phrases/sentences (“text”).

2.3. Development of Advertising-style Messages

The teams co-developed the advertising-style messages in an iterative fashion described further below. Briefly, the advertising team developed the initial 11 messages. The research team used a preliminary survey to evaluate these and identified five for refinement and further testing in focus groups. Focus group feedback then informed the selection of the final three messages.

2.3.1 Evidence Identification and Synthesis

The advertising team began its standard creative process by familiarizing itself with research evidence of five types:

- Disease—the condition (CKD) and how providers manage it

- Therapeutic—perceived benefits and limitations of treatment options (e.g., ACE inhibitors)

- Company—how specific pharmaceutical companies approach marketing medication for the condition within the context of their product portfolio or competing products

- Brand—how medications for the condition are typically promoted

- Market—patient and prescriber knowledge and attitudes about the condition and its medications

The PI identified and synthesized the first two types of evidence, while the advertising team did the same for the latter three.

2.3.2 Translating Evidence into Persuasive Messages

The advertising team then generated the creative work plan, which identified the learning objectives of the advertising campaign and specific barriers to initiation of the promoted medication. The research team reviewed and revised it. The final version served as a consensus document to guide the development process (Appendix 1). The advertising team crafted overarching creative themes that would engage patients. They separately brainstormed message ideas that fit these themes and then deliberated together—discussing message feedback and modifications—until they generated 11 initial messages for testing by the research team.

The research and advertising teams co-developed brief educational information (on CKD and ACE inhibitors) written in simple, patient-appropriate language (Appendix 2). It was designed to be packaged with the messages, read after patient attention was already engaged, and support patients at the rational level by building knowledge. The information was tested in focus groups only.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Recruitment

For patients, inclusion criteria for the preliminary survey were more permissive than those for focus groups. Survey patients were required to have one or more of these conditions: CKD stages 3–4 (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 15–59 mL/min/1.73m2) [8], type 2 diabetes, or hypertension (because the latter two conditions are the most frequent etiologies of CKD). Patient focus group inclusion criteria were Stage 3b CKD (eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73m2) or Stage 3a (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73m2) [8] with additional risk factors for progression (specifically, poorly controlled diabetes and/or hypertension), no current use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and no allergy or contraindication to ACE inhibitors. For providers, inclusion criteria for the survey and focus groups were the same—being a practicing primary care provider in outpatient general internal medicine, family medicine, or geriatrics at the main campus of Stanford Health Care (n=32). Exclusion criteria for both patients and providers were non-English speaking and, due to the rapid timeframe of the study, inability to complete the preliminary survey within 1 week of request or inability to attend focus groups at the pre-set times offered. The research team used EHR data to identify eligible patient participants and, among these, the sub-set (n=28) who had given prior consent, as members of the Stanford research registry, to be contacted directly about research projects. The research team recruited among these patients using an invitation email or phone call, whichever the registry listed as their preferred contact method, and among primary care providers by email invitation letter.

2.5. Preliminary Surveys and Message Refinement

The research team used a short hardcopy survey to collect feedback on the 11 initial messages from a convenience sample of six patients and two providers. While the survey has not been independently validated, the advertising team has applied it regularly on prior work and quantitative questions rate messages according to marketing criteria shown individually to predict patient engagement and activation [32–38] (Table 1, upper right). Research personnel administered surveys, while respondents viewed messages on a computer screen. Respondents were told that messages would be delivered electronically to patients by healthcare systems or providers. Survey goals were (a) for patients, to identify 3–5 messages that were most compelling to proceed to focus group testing and determine refinements to be made prior to that, and (b) for both groups, to identify negative reactions to specific messages or the approach in general, which would suggest that they be discarded.

Table 1.

Focus Groups: Format and Questions

| Topics Covered(in listed order) | Used in Focus Group(X=yes) | Questions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Provider | ||

| Self-reflection activity | |||

| Advertising-style messagesa | |||

| Impact on patients and patient actions | X | Used5-point Likert scales to answer questions on marketing criteria assessing likely impact of advertisement on patientsb How likely would you be to stop and read this message? How believable is the message conveyed here? How relevant to your health and life is this message? How clearly does this message communicate? How likely would you be to take action in some way after seeing this message? | |

| Impact on patient-provider relationship | X | _Encouraged to write down thoughts, if desired:_Is there anything about the message that would help, hinder, or otherwise affect your work with a patient? | |

| Group discussion | |||

| Advertising-style messagesa | |||

| Reactions to each message | X | X | Can you tell us what aspects of this message you particularly liked, disliked, or had a strong reaction to? |

| Impact on actions | X | Imagine that you saw this message in your daily life. Ask yourself, would it motivate you to take action in any way? If so, how would you take action in your life? If not, can you imagine changes to it that would make it more likely to motivate you personally? | |

| Impact on patient-provider relationship | X | Is there anything about the message that would help, hinder, or otherwise affect your work with a patient? | |

| Educational information | |||

| General reactions and impact on patient-provider relationship | X | X | Patientc: Can you comment on aspects of the information that stand out in your mind?Provider: Is there anything about the informational materials that would help, hinder or otherwise affect your work with a patient? |

| Other materials desired | X | X | Patient: Can you tell us what additional information would be most useful for you to know?Provider: Are there other materials you might want the patient to bring into a conversation they initiated with you? |

After determining that patient quantitative and narrative feedback were aligned (e.g., high Likert scale scores aligned with positive narrative feedback), the research team used survey responses to identify the most persuasive messages. For each patient, messages were ranked from favorite to least favorite based on the sum of their scores (possible range 5–25) and their top-5 lists were recorded. The research team determined that there was consistency regarding highest-ranking messages across patients, identified the five highest-ranking messages to proceed in testing, and used narrative feedback to refine them.

2.6. Focus Groups and Message Testing

The research team PI facilitated two semi-structured focus groups with patients and two with providers. RAs collected field notes using a template grid [39] and performed digital MacBook audio-capture. Patient focus groups lasted 90 minutes, while provider sessions were 60 minutes. A professional transcriptionist transcribed audio-capture. Participants received $20 gift cards as compensation.

Prior to group discussion, participants performed a silent self-reflection activity—using paper printouts of the advertising-style messages—that was designed to prepare them to share their perspectives during group discussion (Table 1, upper rows). Patients were asked to consider whether the messages were compelling (using the same marketing criteria as the preliminary survey). Providers were asked whether the messages would influence their work with patients. Participants were encouraged to write notes for their own use.

During group discussion, messages were projected on a large screen. The facilitator asked questions using a funnel approach (Table 1) [39]. For patients, discussion began with general reactions to each message followed by targeted questions on its motivational nature. For providers, questions focused on aspects of the message that would help, hinder, or otherwise affect their interactions and relationships with patients.

Participants from one patient and two provider focus groups were asked about the educational information. (Table 1) In the second patient focus group, participants were not shown the information because of time constraints but were asked to describe what educational information, if any, they would like to receive with the messages.

2.7. Data Analysis and Selection of Final Messages

Research team members (VY, ET, JP) independently applied content analysis to focus group transcripts and field notes to identify inductive codes [39, 40]. They then iteratively developed thematic categories (themes) from the codes [39]. Next, each team member independently returned to original quotes to review and modify how they were mapped to themes and to confirm and refine themes. Circulation of individual notes on these processes followed by group discussion confirmed agreement on final themes [39].

The research team next identified and grouped together themes related to the general approach of using advertising-style messages. The team felt it was important to assure that the approach did not undermine the therapeutic alliance between patients and providers. The team also identified themes related to individual messages. It felt it was important to better understand why individual messages were (or were not) persuasive to add to the nascent literature on medication marketing within healthcare systems and ensure that selected messages were complementary, but not duplicative, in the emotional barriers they overcame and their means of doing so (if elucidated). Finally, the research team used themes on individual messages to select those with the highest potential for impact in real-world settings.

The Stanford Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Participants provided written informed consent.

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility of Partnership

The research and advertising teams agreed on the basic partnership structure (necessary expertise, responsibilities, and workflows), fees, and timeframe prior to project initiation and made only minor modifications subsequently. The project was completed relatively rapidly and inexpensively. (Figure)

Figure 1.

Feasibility: Partnership Responsibilities, Workflow, Timeframe, and Costs

3.2. Preliminary Surveys

Five of 11 initial messages had cumulative survey scores that placed them on the top-5 lists for three or more of six (≥ 50%) patients and one or more of two (≥ 50%) providers. Narrative feedback suggested specific modifications to improve message impact: avoid wordiness and jargon (e.g., “what does ‘therapy’ mean?”) and make stronger visual connections between imagery and text components (e.g., “move words closer to picture”). Neither patient nor provider feedback identified objections to the general approach or highest-ranking messages.

3.3. Focus Groups

The research team attempted contact with 28 patients deemed eligible for focus groups. Focus groups were only offered at two times occurring within two weeks of attempted contact. Nine patients were not reachable, four were not interested, and eight had scheduling conflicts. Seven of 28 (25%) eligible patients participated in two focus groups: mean age was 59 years (range 51–69), five (71%) were men, four (57%) had diabetes, and six (86%) had hypertension. Two provider focus groups were conducted with six of 32 (19%) eligible primary care providers: three general internal medicine and three family medicine physicians.

3.3.1 Acceptability Of General Approach

Patient and provider themes were similar. Some patients expressed a general suspicion of messages that were sent or appeared to be influenced by the pharmaceutical industry, while providers were skeptical of medication requests that did not have “good science” supporting them. (Table 2A, Row 2A.iv) But if certain conditions were met, both groups favored the general approach of using advertising-style messages to engage patients (Rows 2A.i–iii). Acceptable messages were those that supported a positive, therapeutic patient-provider relationship (Row 2A.i) and had a credible evidence base (Row 2A.iii). Patients characterized them as a kind of public service announcement, while providers characterized them as a useful means of priming patients for clinic visits.

Table 2.

Acceptability of general approach of using advertising-style messages and educational information with patients

| 2A. Acceptability of Advertising-Style Messages | ||

|---|---|---|

| Themes | Sub-Themes (as indicated) and Representative Quotes | |

| General approach is acceptable if it… | Patients | Providers |

| Supports patient- provider relationship | Prompts good conversation/collaboration | |

| Row 2A.i | “… It would motivate me to talk to my doctor about ACE inhibitors and what it would do to protect my kidneys.”“Yes, I would talk to my doctor, you know, I would ask – at least I would ask what ACE inhibitor is and does it apply to me? Can it help me? ”“The next doctor’s visit… I would say, “Hey, doc. What do you think about my kidneys?…” It would make me ask questions.” | “I like… the concept of embracing treatment, it gives a cooperative type of—it makes me think of a cooperative relationship between the patient and the physician. It’s like, oh, I saw this and I'm ready! I'm open now to taking this treatment. I heard about this and I'm open to it if you want to suggest it to me….”“I actually really appreciate the fact that they [patients], I assume, looked into many things. You know a lot of patients will do a lot of individual research on their own and they seem very – like they’ve thought about the science, all these different things. I appreciate that, so then we have a very good conversation.” |

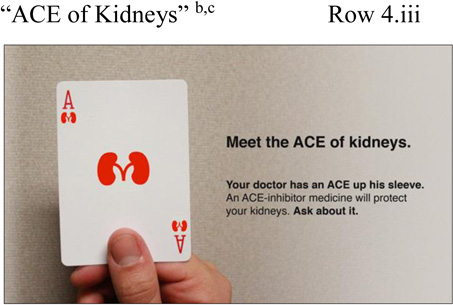

| Does not undermine patient trust in provider | ||

| Row 2A.ii | “I assume already that my doctor is giving me the best stuff that he can give me now, you know, that’s available, and I have a great deal of admiration for my doctor. I mean, he’s a wonderful person, and that just kind of said, “I've got to ask him, why didn’t he tell me about it? He knows I'm ignorant and, you know, as far as anything in that category, for sure, you know.” | Exchange between providers regarding theACE of Kidneys message: “… Seeing playing cards, you know, you think like poker and you think of someone sort of surreptitiously keeping this thing like up his sleeve…. I was thinking maybe the patient would come in with a little bit more distrust….” “Yeah, I had similar thoughts. I just felt like [this message] made me uncomfortable because it makes it seem like the doctor has not been telling them about something.” |

| Has an appropriate evidence base supporting it | Credible source(patient depends on credible/trustworthy source— e.g., person, web site—for knowledge translation) | Medical evidence favorable(provider comes to own determination regarding evidence—e.g., studies) |

| Row 2A.iii | “I would want to know if I could corroborate that this medication actually does have a positive effect. There may be some websites I can go to….As long as I feel it’s a trusted source, it would be fine for me…. If it’s at Stanford or Columbia, you know, Harvard – you know those kinds of things would make me believe it’s probably more credible.”“I think that if the doctor handed it to me, I would value that.” | “Sometimes I’m very grateful for what the patients might bring up. You could use the example of immunizations. As much as I want to be on the ball all the time, sometimes I do forget to recommend the shingles vaccination to somebody…, and I’m grateful – I’m so glad you brought this up! This is absolutely appropriate. I think it – some of the difference between the negative and positive emotions, the resistance versus the gratitude or relief or whatever, is the level of appropriateness of the request.” |

| Suspicious/untrustworthy source | Medical evidence unfavorable | |

| Row 2A.iv | “I feel a little suspicious of [some information] because it all is coming from the—like the pharmaceutical industry is influencing them to send it to me kind of thing.” | “I think my response to a request like that really depends on how appropriate it is. I’ve had requests that are just really out there or that don’t have a lot of good science behind them.” |

| 2B. Acceptability of Educational Information | ||

| General approach is acceptable if it… | Patients | Providers |

| Primes patient with basic information Row 2B.i | “To put that in the ads also? Yeah, I think that would be a great idea. I think most people would just talk to their doctor, just when they see the message. But for those who want more, if there’s a source that looks credible and you could put that in the message, it’s terrific.” | “I think that this information—these informational materials would help my work with a patient…. It’s just enough and good background information.”“I like all of these. I like [other provider’s] idea, sort of prime the patient.”“It’s one of those things where I think it has a very positive bent to it where, as a patient, I would be really willing to talk to that, consider that.” |

Both groups endorsed having educational information accompany the messages, viewing it as further preparing patients for productive medication discussions. (Table 2B, Row 2B.i) But they highlighted the importance of matching message content to the level of patient sophistication and adding even more medication information—drug names, possible side effects.

3.3.2 Potential Impact of Messages

General Themes

Patient and provider themes identified individual message characteristics that predicted greater impact in real-world settings. (Table 3) Messages were more likely to capture attention if their imagery resonated with the viewers, particularly in a positive manner—through identification with people or positive associations with symbols or objects. (Table 3, Rows 3.i–ii & 3.iv) Second, the emotional tone of the messages elicited complex responses: a tone that was too scary or negative was experienced as a barrier to engagement (Row 3.iii), but one that was positive or had a sense of urgency was felt to be a strong motivator for action (Rows 3.iv–v). Finally, messages that promoted a sense of patient self-advocacy and were clear (versus confusing) were more likely to be compelling (Rows 3.vi–vii).

Table 3.

Potential impact: General message characteristics that are suggestive of higher real-world impact

| Themes and Sub-themes | Representative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | Provider | |

| Personal Identification with Imagery | ||

| Imagery of humans—identification with those pictured is important Row 3.i | “I picture myself with that lady right there,… that picture of somebody that I really—I like.”“… We are senior citizens and we have lived a lot of our life already. And I'm not just saying that I am giving up or anything like that, but like to see the kid and say, oh, man, he… needs every chance he can get…. I look at that and there’s something there for me that I can relate to. My kids are grown. I just became a grandfather, actually a couple weeks ago…. But, yeah, anytime I see a kid, I've got to kind of put that at the front of the line with me.” | “… Let’s say this patient reads this and they relate to this person that’s looking back at them so they do decide to talk to their doctor…. Because this lady is just—she’s concerned and friendly….”“It’s a good choice of race, also, because I think the trip to kidney failure among African Americans is actually a lot more progressive than in the rest of the populations.” |

| Imagery of symbols/objects—resonance/associations with these are important Row 3.ii | Exchange between 2 patients: “I think the red phone is also smart because, you know, like the President, I think, has a red phone and he can talk to the Kremlin anytime, you know, stop the nukes from flying kind of thing. So that’s—I can see why they would use a red phone on that.” “Actually, we have a red phone, too, and—… a lot of work that I do have that phone…and disaster.” “Oh, so you have another association with it. Oh.” “Yeah. Don’t let that phone ring! I don’t want to do nothing with that phone!” “That would explain why you didn’t like it!” | “The phrase ‘ACE up his sleeve’ reminds me of somebody who is doing a magic trick, right?… And then the other thing is that, you know, the ACE of kidneys, the ace up his sleeve, it makes me a little bit concerned that this is like a miracle cure, like as long as you take this ACE you will never need dialysis. You will never need—you know, it might be this promise that it’s definitely going to help but, at this point, might make it seem like this is going to do it. You are going to be fine—cured.” |

| Delicate Balance between Negative and Positive Emotional Tone | ||

| Negative/scary emotions are detrimental Row 3.iii | “I had a strong reaction—as I do to commercials on television—‘Ask your doctor.’ I hate that they are making us believe we have all different diseases….” | “For the anxiety prone, I think that may be a little counterproductive…. I can see having to explain a lot more.” |

| Positive emotions can be motivating Row 3.iv | “I don’t play cards but I know what an ace is and I know what winning and what the good things of life are, and I can identify this with something good in my life, you know what I mean?” | “It’s a great photo of a granddad and his grandchild, and that is a motivator to remain healthy. I think there is just a real warmth to that photo….” |

| Sense of urgencyalso can be motivating Row 3.v | “Oh, my goodness! My kidneys are failing slowly. You want to take care of something like that.” | “The ‘quietly failing’… might promote a little bit too much anxiety but, again, that might motivate some people…, so it might be a great motivator for some patients.” |

| Patient Role | ||

| Patient responsibility/self-advocacy is desirable Row 3.vi | “It [the advertising message] raises the question in your mind right away, and then gives you a very subtle ‘there’s something you can do about it’ and kind of makes you take the responsibility.” | “I felt like it built into patient’s self-advocacy: there’s something you can do about it…I am glad patients feel there is something they can do to change what is going on with them.” |

| Varying Degrees of Clarity | ||

| Clear messages engage correct patients vs. Confusing messages cause problems/engage wrong patients Row 3.vii | “This time I really liked how ACE was used, with the ACE of kidneys. That made sense to me…. This, to me, just made it clearer that ACE is some sort of medicine and…find out about it, you know…. And I did think the card—like I liked those—well, it looks like kidneys to me.”“This [advertising message] was a problem. It didn’t kind of tell me what to do and what not to do, you know, … to me, it was confusing.” | “The only thing that I could actually think of that might be confusing—… is that they don’t realize it’s because they have CKD and they show it to everybody in their family…—you know, everybody needs an ACE inhibitor. So, as long as it’s targeted and it’s clear, like you’ve got CKD, that’s why you're getting a message, I think it would be helpful.” |

Message-Specific Themes and Selection of Final Messages

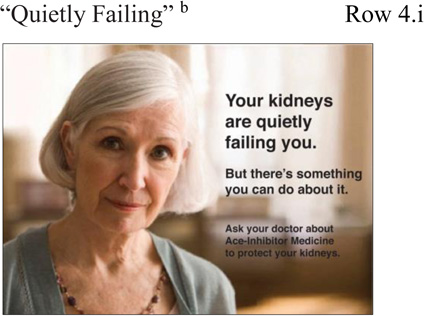

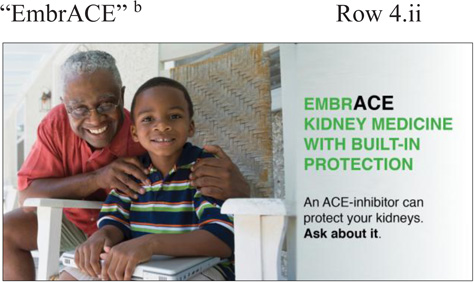

Patients identified messages that provoked positive associations of familiarity, family relationships, responsibility, winning, or a sense of urgency (but without too much fear) as the most compelling ones. (Table 4, Rows 4.i–iii) Messages that prompted emotions of avoidance or confusion were not well received. (Rows 4.iv–v) The research and advertising teams used these themes, in combination with the general themes on potential impact, to identify the three final messages most likely to capture attention and motivate action. (Rows 4.i–iii)

Table 4.

Individual advertising-style messages: content and examples of themes relevant to potential impacton patientsa

| Message and Type of Imagery | Message-specific Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Human Imagery | ||

|

Identification with Human Imagery—Positive Identification as Being Familiar & Other Positive Emotion—Honesty | Exchange between patients: “I love the picture of the lady. She has such a sincere, honest look to me…. Do you know that lady? Does anybody know her? She looks familiar.” “…. Maybe we’ll pass her in the hallway sometime when we come here.” |

| Patient Adoption of Responsibility | “It is now my responsibility. It is not the doctor’s responsibility. It is your kidneys that are failing you know. And then you go take the action.” | |

| Urgency | “It’s telling you the urgency of the message. You and I might not even be aware of it.” | |

|

Identification with Human Imagery—Positive Identification with Relationship/Child & Other Positive Emotion—Sense of Generativity | “Life is too short and if we don’t take care of ourself, we don’t have a chance to see our children growing up.”“You could see, you know, the person who was elderly, spending some time with the kids, wanted to have a valuable time and seeing that, okay, you know I need to start looking at my kidneys, These are children I want to spend my time with.” |

| Symbolic Imagery | ||

|

Identification with Object—Positive Association with Winning | “Everybody can identify with playing cards, or else going to Reno or Tahoe and, you know, and gaming there. The card has to do with game and winning and understanding, and winning, to my mind, is pretty important.”“It’s the game playing, ace is always number one so it just makes you feel like this is an important message for me to take a look at.” |

|

Identification with Object—Negative Association of Avoidance & Other Negative Emotion—Annoyance | Exchange between 4 patients: “This does not attract me at all; number one, telephones. I don’t even answer the telephone at home… I avoid telephones all together….” “Telemarketers.” “Yeah, oh terrible!” “Just exactly what you said.… I’m just not going to answer it because—dude, just stop calling!” |

|

Sense of Confusion | “This is really a puzzle. What is it? Something is missing from my kidney protection? ”“I don’t know, what is that? Because the picture of the kidney, I thought it looks like beans to me…. What is that? Is that a bean or [makes an “I don’t know” gesture with hands].” |

When patients were asked what they would actually do following receipt of such messages, most stated they would make a “mental note” to have a medication discussion during the next clinic visit (e.g., “I use a sticky note…. so that way I would remember to ask her [my doctor]”) or would contact their provider immediately. Some also would seek information from other sources (e.g., online, friends, family).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This study demonstrated the feasibility of a partnership between research and advertising teams and the acceptability and potential impact of advertising-style messages directed at patients with chronic conditions (here, moderate CKD) who are not yet taking indicated medications (ACE inhibitors). The most persuasive messages boosted patient activation by capturing attention and harnessing patient emotions to overcome affective barriers—in ways that could increase their engagement in chronic disease self-care. Other teams with similar goals may want to replicate our partnership and development approach to develop messages of their own.

When we began this project, there was little published evidence on comparable projects that had developed advertising-style messages directed at specific patients with chronic conditions. Interestingly, we independently developed a partnership structure and process similar to those recently outlined by Kravitz and colleagues [41]. The Kravitz research team partnered with a marketing team at a for-profit communications company to develop four public service announcement (PSA)-style video clips (2.5 minutes long) designed to prompt patients to discuss depression symptoms with their primary care providers. The PSAs all were iterations of the same message concept but included different actors chosen to resemble four targeted demographic groups. Kravitz project costs totaled 200,000,andthetimeframewasthreeyears.Incomparison,currentprojecttotalcostswere200,000, and the timeframe was three years. In comparison, current project total costs were 200,000,andthetimeframewasthreeyears.Incomparison,currentprojecttotalcostswere14,550, the timeframe was four months, and we produced three separate digital but static messages (i.e., using a pictorial- rather than video-based delivery format) to be used in a campaign on a single medication class. While costs accrued in the Kravitz project and in our project are not directly comparable because the marketing-style messages developed by each have different delivery formats, our development costs were considerably lower than those of the Kravitz project and also were much lower than the typical pharmaceutical campaign budget, in which development of a single pictorial advertisement like the ones we developed costs in the range of $40–60,000.

In the current project, both patient and provider respondents indicated that the general approach of advertising-style messages would be acceptable in real-world settings as long as certain criteria were met. In prior research, consumers usually have reported neutral to positive attitudes toward DTC advertising [42]. In contrast, providers more often disapprove of DTC advertisements [43], perhaps due to concerns about biased information or patients making inappropriate medication demands [44]. Yet some providers have cited DTC advertising as having a possible benefit of increasing patient-provider communication about treatment options [43, 45], which aligns with feedback in the current study.

Patients in the present study indicated that the most persuasive individual messages captured attention, overcame emotional barriers, and empowered them to inquire about recommended medications. Evidence from others has been similar [46] and suggests that this approach has the potential to decrease under-treatment of chronic conditions. However, given the nascent nature of this research, we recommend that healthcare systems considering use of similar messages test them first to identify not just which ones are most likely to activate patients, but also what emotional barriers each message may be overcoming and in what way. Doing so will help identify how their marketing campaign (depending on its goals) may use selected messages to overcome multiple emotional barriers at once or, alternatively, have a single, unified emotional tone. Importantly, it also will identify and eliminate messages that are too scary or negative. This is essential because our evidence suggests that healthcare providers’ traditional approach of using “scare tactics” in an attempt to prompt medication initiation or adherence may well be backfiring—alienating patients instead of motivating them.

Our partnership and development process has several potential challenges and limitations. First, our research team was fortunate to have members with graphic design expertise and an existing relationship with medical advertising professionals. We recommend health services research teams without such expertise or relationships contact marketing departments at their own or related organizations to determine whether they can recommend graphic designers and creative directors with experience in pharmaceutical advertising. Non-profit organizations may seek help from foundations (e.g., Taproot (www.taprootfoundation.org)) that can identify design and marketing professionals willing to do pro bono or reduced-fee work. Second, we recommend use of a 2-person advertising team as a way to keep development costs relatively low while also approximating the creative process that occurs in the ad agency environment—generation of sufficient ideas and discussion to create effective messages. Third, we recommend that research teams encompass expertise in clinical management of the pertinent condition, health communications, patient engagement/behavior change, and mixed methods research. Fourth, enrollment of subjects in research is always challenging. But we were fortunate to have access to a list of persons who had previously agreed to participate in research, thereby yielding a prospective study sample far more likely to participate than usual. Fifth, our focus groups were relatively small; nonetheless, themes overlapped and converged, and pharmaceutical marketing consultants use similar numbers of participants in their focus groups with resulting good success in the advertisements selected [47]. Finally, because we did not collect participant follow-up data, we could not assess message impact on subsequent patient actions or health outcomes. Health systems may want to examine these—e.g., newly-filled prescriptions or changes in disease control.

4.2. Conclusion

We demonstrated the feasibility of a relatively rapid and inexpensive research-advertising partnership and the acceptability and likely impact of advertising-style messages on patient engagement and activation for medication initiation among those with chronic conditions.

4.3. Practice Implications

Healthcare systems may want to replicate our process of adapting marketing approaches for their own high-risk patients to capture attention, overcome emotional barriers, and empower patients to ask for and initiate recommended medications that can improve their health.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant K23DK097308 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), an investigator seed grant from the Stanford Division of General Medical Disciplines, and an NIH CTSA (award number UL1 RR025744).

We thank the following individuals for their contributions to the design and/or conduct of the project: Joe Garamella (medical advertising professional and member of the advertising team); Kenny Leung (summer undergraduate intern who assisted with focus group analyses). We are especially grateful to the patients and physicians who participated in the surveys and focus groups.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Green is a cofounder of RxBalance.

Contributor Information

Veronica Yank, General Medical Disciplines, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States.

Erika Tribett, General Medical Disciplines, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States.

Lydia Green, RxBalance, Redwood City, CA, United States.

Jasmine Pettis, General Medical Disciplines, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States.

References

- 1.Statistics NCfH. Death and Mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen A, Forman J, Orav E, Bates D, Denker B, Sequist T. Primary care management of chronic kidney disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:386–392. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1523-6. Epub 2010 Oct 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foley R, Am M, Li S, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:489–495. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coresh J, Astor B, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult U.S. population: Third International Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1–12. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu M-J, Shu K-H, Liu P-H, et al. High risk of renal failure in stage 3B chronic kidney disease is underrecognized in standard medical screening. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:515–522. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(10)70113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink H, Ishani A, Taylor B, Greer N, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:570–581. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin A, Hemmelgarn B, Culleton B, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease. CMAJ. 2008;179 doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NKF. Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI): Executive summary. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S17–S31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NKF. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for managing dyslipidemia in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:S1–S58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NKF. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. 2004 Available at http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_commentaries.cfm - guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NKF. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:S13–S19. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder J, Collins A. KDOQI hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes care guidelines and current care patterns in the United States CKD population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:44–54. doi: 10.1159/000201014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Quality Forum. Renal Consensus Standards Endorsement Maintenance 2011. [Accessed July 31, 2014];National Quality Forum. 2014 Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/Renal_Endorsement_Maintenance_2011.aspx - t=2&s=&p=3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibbard J, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data. Health Affairs. 2013;32:207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pibernik-Okanovic M, Prasek M, Poljicanin-Filipovic T, Pavlic-Renar I, Metelko Z. Effects of an empowerment-based psychosocial intervention on quality of life and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Ryan R, Prout H, Cadbury N, et al. Interventions before consultations to help patients address their information needs by encouraging question asking: systematic review. Brit Med J. 2008;337:a485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avorn J, Fischer M. 'Bench to behavior': translating comparative effectiveness research into improved clinical practice. Health Affairs. 2010;29:1891–1900. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanovich K, West R. On the relative independence of thinking biases and cognitive ability. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:672–695. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans J. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:255–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yood R, Mazor K, Andrade S, Emani S, Chan W, Kahler K. Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1815–1821. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines?: A framework for improvement. J Amer Med Assoc. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazor K, Velten S, Andrade S, Yood R. Older women's views about prescription osteoporosis medication. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:999–1008. doi: 10.2165/11584790-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polonsky WH. Emotional and quality-of-life aspects of diabetes management. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2(2):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randolph W, Viswanath K. Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: marketing health in a crowded media world. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:419–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman A, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate health behavior: the role of message framing. Psychol Bull. 1997;121:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher K, Updegraff J. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:101–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MS R. Media and Message Effects on DTC Prescription Drug Print Advertising Awareness. Journal of Advertising Research. 2003;43(02):180–193. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woloshin S, Schwartz L, Tremmel J, Welch H. Direct-to-consumer advertisements for prescription drugs: what are Americans being sold? Lancet. 2001;358:1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sejung Marina C, Wei-Na L. Understanding the impact of direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising on patient-physician interactions. Journal of Advertising Research. 2007;36:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeNelsky S. e-health: Getting Connected in a Digital Age. Health Care Information Services, ING Baring Furman Selz LLC. 1998 URL: http://www.tapoventures.com/e-health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox C, Vest B, Kahn L, Dickinson L, et al. Improving evidence-based primary care for chronic kidney disease: study protocol for a cluster randomized control trial for translating evidence into practice (TRANSLATE CKD) Implement Sci. 2013;8:88. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pieters R, Wedel M, Batra R. The stopping power of advertising: measures and effects of visual complexity. Journal of Marketing. 2010;74:48–60. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews J, Netemeyer R, Durvasula S. Believability and Attitudes toward Alcohol Warning Label Information: The Role of Persuasive Communications Theory. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 1990;9:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muehling D, Stoltman J, Grossbart S. The impact of comparative advertising on levels of message involvement. Journal of Advertising Research. 1990;19:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houts P, Doak C, Doak L, Loscalzo M. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duncan C, Nelson J, Frontczak N. The effect of humor on advertising comprehension. Advances in Consumer Research. 1984;11:432–437. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein N, Cialdini R, Griskevicious V. A room with a viewpoint: using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35:472–482. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Block L, Keller P. When to accentuate the negative: the effects of perceived efficacy and message framing on intentions to perform a health-related behavior. Journal of Marketing Research. 1995;32:192–203. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krueger R. Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews. University of Minnesota: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas D. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American Journal of Evaluation. 2003;27:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kravitz R, Epstein R, Bell R, Roclen A. An academic marketing collaborative to promote depression care: a tale of two cultures. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polen H, Khanfar N, Clauson K. Impact of direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) on patient health-related behaviors and issues. Health Market Q. 2009;26:42–55. doi: 10.1080/07359680802473521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsky M, Taylor C. he opinions and experiences of family physicians regarding direct-to-consumer advertising. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grenard J, Uy V, Pagan J, Frosch D. Seniors’ perceptions of prescription drug advertisements: A pilot study of the potential impact on informed decision making. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, Lee K. Direct-to-consumer advertising: physicians’ views of its effect on quality of care and the doctor-patient relationship. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:513–524. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ventola C. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: therapeutic or toxic? Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011;36:681–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marketing Research Association. Focus Groups. [Accessed July 31, 2014];Marketing Research Association. 2014 Available at http://www.marketingresearch.org/focus-groups. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1

Appendix 2