Adjuvant sorafenib after heptectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage C hepatocellular carcinoma patients (original) (raw)

Abstract

AIM: To investigate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant sorafenib after curative resection for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC)-stage C hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Thirty-four HCC patients, classified as BCLC-stage C, received adjuvant sorafenib for high-risk of tumor recurrence after curative hepatectomy at a tertiary care university hospital. The study group was compared with a case-matched control group of 68 patients who received curative hepatectomy for HCC during the study period in a 1:2 ratio.

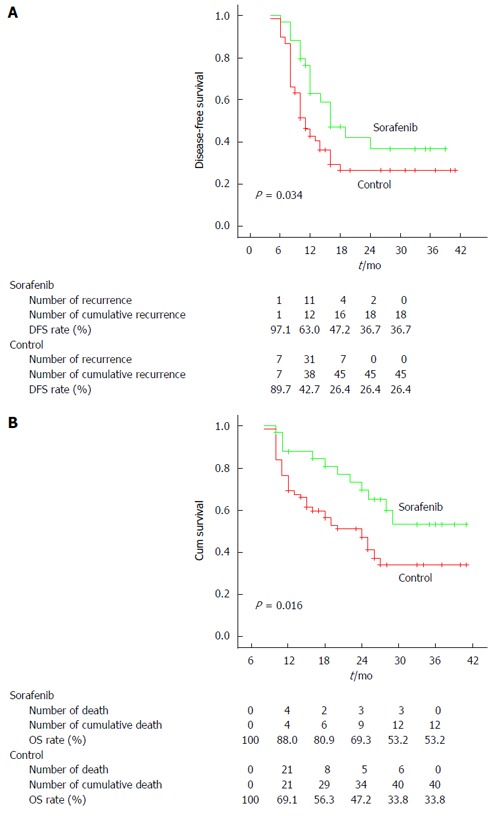

RESULTS: The tumor recurrence rate was markedly lower in the sorafenib group (15/34, 44.1%) than in the control group (51/68, 75%, P = 0.002). The median disease-free survival was 12 mo in the study group and 10 mo in the control group. Tumor number more than 3, macrovascular invasion, hilar lymph nodes metastasis, and treatment with sorafenib were significant factors of disease-free survival by univariate analysis. Tumor number more than 3 and treatment with sorafenib were significant risk factors of disease-free survival by multivariate analysis in the Cox proportional hazards model. The disease-free survival and cumulative overall survival in the study group were significantly better than in the control group (P = 0.034 and 0.016, respectively).

CONCLUSION: Our study verifies the potential benefit and safety of adjuvant sorafenib for both decreasing HCC recurrence and extending disease-free and overall survival rates for patients with BCLC-stage C HCC after curative resection.

Keywords: Hepatectomy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Sorafenib, Survival, Tumor recurrence

Core tip: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has a 5-year recurrence rate reaching 80%-90% even after potentially curative treatment. Therefore, it is extremely important to prevent recurrence for the prognosis of HCC patients. Sorafenib is the only approved treatment for patients with advanced HCC. Thus, based on the action of sorafenib, namely inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, there is rationale for the study of sorafenib as an adjuvant therapy in HCC. It is essential to investigate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant sorafenib administered following curative resection in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage C HCC.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is increasing globally in conjunction with increasing prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the West and of both hepatitis B and C in Asia[1]. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for HCC, according to guidelines and consensus coming from all over the world[2-4]. Most HCC patients are in the advanced stage of disease on initial diagnosis[5,6]. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, surgical resection should only be used on a very small population of patients with very early staged HCC, while sorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, is recommended as the treatment for advanced HCC. However, patients with advanced HCC who receive sorafenib achieve a median gain in overall survival (OS) of around 3 mo[7-9]. Therefore, additional management strategies need to be identified to improve therapeutic benefits. Hepatectomy for advanced HCC patients remains controversial, although previous studies showed survival benefit in patients with more advanced HCC[10]. However, early tumor recurrence is common after hepatectomy for HCC with macrovascular invasion, multinodular or large HCC. There is still no acknowledged adjuvant therapy for HCC after radical surgery, and tumor recurrence is still the main cause of death for these patients. It has been reported that sorafenib can be used as an adjuvant therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence after potentially curative treatment in animal research and in pilot clinical studies[10-13]. Feng et al[12] reported that sorafenib suppressed development of postsurgical intrahepatic recurrence and abdominal metastasis, which consequently led to prolonged postoperative survival, in an orthotopic xenograft model of HCC. Saab et al[13] demonstrated the safety and potential benefit of sorafenib, in both reducing HCC recurrence and extending disease-free survival (DFS) and OS rates, in their study of eight high-risk liver transplant recipients. Thus, further research on the efficacy of sorafenib in decreasing HCC recurrence after liver resection in high-risk patients is urgently needed. In this study, sorafenib was used as an adjuvant therapy to decrease the risk of tumor recurrence following potentially curative resection in patients with HCC of BCLC-stage C. The efficacy and safety of this modality were evaluated in this case-matched comparative study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

From September 2010 to September 2013, 41 HCC patients classified as BCLC-stage C received adjuvant sorafenib after curative liver resection. This is a retrospective study on data that were prospectively collected and entered into a computer database. All patients were histologically confirmed to have HCC in the resected specimens. The definition of BCLC-stage C was: any tumor with radiological and histological evidence of macrovascular invasion (portal vein, hepatic vein, inferior vena cava). Patients with lymph nodes (Hilar lymph nodes excluded) and/or distant metastases[2,8], tumor recurrence diagnosed within 2 mo of operation, or who had received any other forms of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy were excluded. Patients in the sorafenib group were recruited if they agreed to take adjuvant sorafenib. Each patient in the study group was matched, as closely as possible, with two BCLC-stage C patients for tumor size (± 1 cm in diameter), tumor number, tumor location, type of operation and Child-Pugh grading from a prospectively maintained database of 1335 patients who received R0 liver resection for stage BCLC A/B/C HCC during the study period (the control group). The demographics, blood biochemistry, tumor characteristics, surgical variables, length of hospital stay, and postoperative complications were compared. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Southwest Hospital before the study began; it conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for their data to be used for research purposes.

Preoperative assessments

The patients were evaluated pre-operatively according to the routine procedure of our institute, as previously reported[14]. All patients underwent the same preoperative evaluation protocol that included percutaneous ultrasonography (US), spiral computed tomography (CT) of the thoraco-abdomen (from March 2010 in our institute), CT angiography of hepatic artery/hepatic vein/portal vein, electrocardiogram and blood biochemistry. Liver function was assessed by the Child-Pugh grading system (A or B) and indocyanine green clearance test at 15 min (ICG15; less than 10%). The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 0 or 1 in this study. The liver volume to be resected and the future liver remnant volume (FRLV; more than 50% in cirrhosis and 40% in normal) were calculated using computed tomographic volumetry (UniSight, China), according to the method described by Urata et al[15].

Partial hepatectomy

The operation was performed as previously reported using a right subcostal or a midline incision with a right horizontal extension[16]. After excluding any unexpected intraperitoneal metastasis, intraoperative ultrasonography was used routinely to clarify the extent of tumor, detect tumor nodules in the contralateral hemiliver and invasion of tumor into major blood vessels, and to plan and mark the plane of liver transection. An intermittent Pringle’s maneuver with clamp/unclamp times of 15/5 min by a tourniquet was used during liver transection using a clamp crushing technique. A low central venous pressure was applied routinely. The extent of hepatic resection was defined anatomically according to Couinaud’s liver segmentation. Major hepatectomy was defined as resection of three or more liver segments. Blood transfusion was only given when the hemoglobin fell below 8.0 g/L. All patients received the same postoperative care by the same team of surgeons and were nursed in the surgical intensive care unit during the early postoperative period. Parenteral nutritional support was provided for patients with cirrhosis. All intra- and post-operative complications were recorded prospectively. Biliary leakage was diagnosed when the total bilirubin level in the drainage fluid exceeded the upper normal limit of serum bilirubin (21 μmol/L) on or after postoperative day 7.

Conventional surveillance strategy and sorafenib

After hepatectomy, patients were routinely monitored with thoraco-abdominal CT scans once every 2 mo for the first 6 mo, and then alternating between abdominal US and CT scan every 2 mo thereafter. Blood for α-fetoprotein (AFP) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) load were also checked at each of the follow-up visits. For patients with a high viral load (HBV DNA > 1 × 103 copies/mL), nucleoside analogues were given. Intrahepatic tumor recurrence was confirmed with imaging, AFP and/or histology. Whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG PET/CT) was used to assess extra-hepatic metastasis. Recurrence time was calculated from the date of operation to the date of diagnosis of tumor recurrence or the date of censor of this study on June 31, 2014. The start point of survival analysis is the day of liver resection.

Sorafenib treatment would be initiated in the first month after surgery following receipt of formal consent from the patient, which was given as free choice by himself/herself. Patients in the sorafenib group were given sorafenib at a dose of 400 mg twice daily. Patients treated with sorafenib were followed-up closely for any adverse effects on an outpatient basis, with reduction in dosage or discontinuation when the drug was poorly tolerated according to the commonly used criteria for adverse events 3.0. Monitoring of complete blood count, blood biochemistry, contrast CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging were performed for evaluation of tumor recurrence every two months, similar to the control group of patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the χ2 test, the Fisher’s exact test or the generalized linear model to compare discrete variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables. DFS and OS rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Potential factors associated with DFS after resection were analyzed using univariate and multivariate analyses. Univariate analysis was performed for 21 risk factors, and significant risk factors were subsequently analyzed by multivariate analysis using a stepwise Cox’s proportional hazard regression model to identify independent prognostic factors for predicting DFS. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 for Windows computer software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

The patient demographics and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups of patients. The median follow-up was 26 mo and 25 mo for the sorafenib group and the control group, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics

| Clinical parameter | Sorafenib | Control | P value2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 34 | 68 | - |

| Males | 25 | 50 | - |

| Age, yr1 | 48 (21-78) | 57 (18-79) | 0.142 |

| Platelet count, 109/L1 | 121 (31-368) | 156 (30-317) | 0.046 |

| Serum albumin, g/L1 | 38 (26-52) | 36 (24-51) | 0.387 |

| Serum total bilirubin, mmol/L1 | 14.6 (5.1-48.3) | 16.4 (7.6-51.5) | 0.283 |

| AST, IU/L1 | 56 (11-526) | 59 (12-498) | 0.525 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L1 | 12.5 (6.6-18.6) | 11.5 (5.9-17.3) | 0.275 |

| AFP ≥ 400, mg/L | 23 | 45 | 0.882 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | 29 (93.3%) | 59 (92.0%) | 0.692 |

| ICG retention at 15 min, %1 | 7.7 (1.5-14.2) | 7.3 (2.3-13.8) | 0.482 |

| Child–Pugh grade, A/B | 27/7 | 54/14 | - |

| HBV DNA, > 1/≤ 1 × 105 copy/mL | 26/8 | 49/19 | 0.634 |

| Prothrombin time, s1 | 14 (10-17) | 14 (10-19) | 0.224 |

| Tumor size, cm1 | 6.4 (2.8-20.2) | 5.9 (2.9-21.3) | 0.098 |

| Tumor number1 | 2 (1-8) | 2 (1-10) | 0.187 |

| Hilar lymph nodes metastasis, yes/no | 11/23 | 29/39 | 0.315 |

| Liver cirrhosis, yes/no | 30/4 | 60/8 | - |

| ECOG performance status score, PS = 0/1 | 31/3 | 61/7 | 0.814 |

| Median follow-up time, mo | 26 | 25 | - |

Surgical variables and outcomes are shown in Table 2. Postoperative aspartate aminotransferase (AST) on day 3 was significantly lower in the sorafenib group than in the control group (P = 0.042). There were no marked differences between the two groups for the types of resection, intraoperative blood loss/transfusion and postoperative total bilirubin levels on postoperative day 3. The main complications were summarized as infectious and noninfectious morbidity. There was no in-hospital or 90-d mortality in this study. There was no significant difference in the overall morbidity rates (P = 0.853). All patients with pleural effusion and bile leakage recovered after percutaneous drainage.

Table 2.

Surgical outcomes

| Variable | Sorafenib | Control | P value2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of resection | - | ||

| Minor | 8 | 16 | |

| Major3 | 26 | 52 | |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mL1 | 350 (50-1600) | 380 (50-1800) | 0.132 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion, mL1 | 650 (0-1500) | 600 (0-1600) | 0.126 |

| No. of patients without transfusion, % | 31 (75.0%) | 58 (81.48%) | 0.139 |

| Postoperative AST on day 3, IU/L1 | 226 (48-896) | 327 (68-1237) | 0.042 |

| Postoperative total bilirubin on day 3, mmol/L1 | 42 (19-276) | 39 (18-212) | 0.138 |

| Infectious morbidity | 8 | 12 | 0.566 |

| Lung infection | 3 | 4 | |

| Abdominal collection | 4 | 6 | |

| Infection of incisional wound | 1 | 1 | |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 | |

| Noninfectious morbidity | 4 | 9 | 0.853 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 | 5 | |

| Bile leak | 1 | 4 | |

| Liver failure | 0 | 0 |

The type of recurrence was divided into hepatic lesion and extrahepatic lesion (Table 3). The total recurrence was significantly lower in the sorafenib group (15/34, 44.1%), as compared to the control group (51/68, 75%, P = 0.002). The overall hepatic recurrence was also markedly lower in the sorafenib group (P = 0.008).

Table 3.

Type of recurrence

| Type of recurrence | Sorafenib | Control | P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic | 8 | 28 | 0.079 |

| Extrahepatic | 5 | 12 | 0.707 |

| Hepatic + extrahepatic | 2 | 11 | 0.142 |

| Overall hepatic recurrence | 10 | 39 | 0.008 |

| Overall extrahepatic | 7 | 23 | 0.167 |

| Total recurrence | 15 (44.1%) | 51 (75.0%) | 0.002 |

Table 4 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate analyses for the 21 selected variables. Of these variables, tumor number more than 3, presence of macrovascular invasion, positive hilar lymph nodes metastasis and treatment with sorafenib were significantly correlated to DFS. Multivariate analysis by Cox’s proportional hazard model showed that tumor number more than 3 and treatment with sorafenib were independent significant risk factors of DFS.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of potential risk factors of tumor recurrence

| Risk factors1 | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value (Cox’s regression) | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value (Cox’s regression) | |

| Sex, male/female | 1.159 | 1.934-1.402 | 0.118 | |||

| Age, > 50/≤ 50 yr | 1.003 | 0.961-1.012 | 0.751 | |||

| Platelet count, > 100/≤ 100 × 109/L | 1.258 | 0.939-1.626 | 0.095 | |||

| Hemoglobin, > 10/≤ 10 g/L | 1.119 | 0.867-1.411 | 0.089 | |||

| Serum AFP, > 400/≤ 400 ng/mL | 0.960 | 0.929-1.011 | 0.079 | |||

| HBV infection, yes/no | 0.931 | 0.593-1.449 | 0.769 | |||

| HBV DNA, > 1/≤ 1 × 105 copy/mL | 1.323 | 0.912-1.883 | 0.119 | |||

| AST, > 42/≤ 42 IU/L | 1.171 | 0.933-1.425 | 0.127 | |||

| Serum albumin, > 38/≤ 38 g/L | 1.264 | 0.961-1.665 | 0.095 | |||

| Serum total bilirubin, > 21/≤ 21 mmol/L | 0.965 | 0.923-1.010 | 0.075 | |||

| Prothrombin time, > 12.8/≤ 12.8 s | 1.162 | 0.931-1.324 | 0.126 | |||

| ICG retention at 15 min, > 10%/≤ 10% | 1.349 | 0.903-1.989 | 0.115 | |||

| Child-Pugh grade, A/B | 1.011 | 0.914-1.097 | 0.779 | |||

| Tumor size, > 50/≤ 50 mm | 0.957 | 0.904-1.014 | 0.075 | |||

| HBsAg, positive/negative | 1.241 | 0.948-1.649 | 0.094 | |||

| HBeAg, positive/negative | 1.174 | 0.938-1.422 | 0.121 | |||

| Type of resection, minor/major | 1.131 | 0.949-1.381 | 0.086 | |||

| Tumor number, < 3/≥ 3 | 2.050 | 1.051-3.549 | 0.034 | 1.324 | 1.035-1.776 | 0.045 |

| Macrovascular invasion, yes/no | 1.242 | 1.061-1.501 | 0.035 | |||

| Hilar lymph nodes metastasis, yes/no | 1.058 | 1.006-1.111 | 0.043 | |||

| Sorafenib, yes/no | 1.012 | 1.003-1.099 | 0.034a | 1.353 | 1.012-1.763 | 0.039 |

The DFS and cumulative OS rates in the sorafenib group were significantly better than those in the control group (P = 0.034 and 0.016, respectively) (Figure 1). The median DFS was 12 mo for the sorafenib group and 10 mo for the control group. Meanwhile, the median cumulative OS was 25 mo for the sorafenib group and 18 mo for the control group.

Figure 1.

Survival analysis in the sorafenib group and control group. A: Disease-free survival; B: Cumulative survival. DFS: Disease-free survival; OS: Overall survival.

Sorafenib was generally safe and well tolerated, with only grades 1 and 2 drug-related adverse events (14 patients, 41.2% in this study). Overall, 9 of 34 patients (26.5%) required a dosage reduction for adverse effects of sorafenib, and most patients recovered (n = 6). The remaining 3 patients were kept on half dose. The mean duration of sorafenib treatment was 22.9 mo. Viral loads were controlled satisfactorily with nucleoside analogues in most of the patients. However, 5 patients required a combination of antiviral drugs (lamivudine + adefovir dipivoxil) to control the viral load.

DISCUSSION

Since tumor recurrence remains a major obstacle to good survival for HCC patients following curative resection for locally advanced HCC, an effective adjuvant therapy becomes important. Recently, sorafenib has been shown to be effective for patients with advanced HCC with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis[9]. The present study showed that sorafenib prolonged DFS and OS by reducing tumor recurrence after curative resection for locally advanced HCC in BCLC-stage C patients.

The role of liver resection for patients with locally advanced HCC has remained controversial until now. The BCLC classification has been endorsed by the European Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease as the best staging system and treatment algorithm for HCC[2,4]. Patients with BCLC-stage C HCC are recommended to receive sorafenib only. However, there have been many retrospective studies in which aggressive surgical therapy was shown to improve long-term survival in the selected patients with locally advanced HCC[10]. The main arguments against resectional surgery for these patients are early recurrence and metastases. Llovet et al[9] and Bruix et al[5] advocated that research efforts should be focused on adjuvant setting of resection, local ablation or combination therapy. Animal studies have indicated sorafenib inhibited tumor growth and prevented tumor recurrence after resection of HCC[12,17]. Feng et al[12] used a luciferase labeled orthotropic xenograft model of HCC to examine the role of sorafenib in prevention of HCC recurrence and demonstrated that sorafenib suppressed development of postsurgical intrahepatic recurrence and abdominal metastasis, which led to prolonged postoperative survival in mice. Wang et al[17] demonstrated that sorafenib inhibited tumor growth and prevented metastatic recurrence after resection of HCC in nude mice. There were also a few clinical reports on the effect of sorafenib in prevention of tumor recurrence[13,18]. A group from the University of California Los Angeles performed a retrospective case-matched study that included eight HCC patients who tolerated adjuvant sorafenib after orthotopic liver transplantation. This study demonstrated the safety and potential benefit of sorafenib in both reducing HCC recurrence and extending DFS and OS for high-risk liver transplant recipients[13]. Recently, a pilot study was conducted on adjuvant sorafenib for HCC patients (31 patients) who underwent curative liver surgery and had high-risk factors for tumor recurrence[18]. The time to recurrence and disease recurrence rate were assessed and showed that adjuvant sorafenib for HCC prevented early recurrence after hepatic resection. The significantly lower cumulative recurrence-free survival rate also demonstrated the preventive effectiveness of sorafenib. All these data strongly suggest that sorafenib has a potential role to play in patients with locally advanced HCC after hepatectomy with curative intention. A phase III randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether sorafenib could be used as an effective adjuvant therapy after resection or ablation (STORM trial, NCT00692770) was reported by Bruix et al[19] recently. The study showed the trial did not meet its main endpoint of improving recurrence-free survival. Nevertheless, the inclusion criteria of the STORM trial was very narrow (for surgical resection: single tumor of ≥ 2 cm without microscopic vascular invasion, without tumor satellites and histologically well- or moderately-differentiated, or any size single lesion but must be ≥ 2 cm if well-differentiated; for local ablation: single tumor > 2 cm or ≤ 5 cm, or 2-3 lesions with each ≤ 3 cm in size). As all these patients were classified as BCLC early stage (A), the impact of sorafenib on these patients after curative hepatectomy may have been insufficiently robust to be demonstrated in that study. On the contrary, there is a recently published review in which a meta-analysis confirmed that the combination therapy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib in patients with intermediate or advanced stage HCC can improve OS, time to progression and objective response rate[20].

In our study, tumor number more than 3, presence of macrovascular invasion and positive hilar lymph nodes metastasis were identified as factors with the highest risk of tumor recurrence. Sorafenib was well tolerated in most of our patients. A literature review was conducted on the prognosis of BCLC-stage C HCC patients treated with either sorafenib or liver resection alone (Table 5). The median overall survival was better in the groups treated with liver resection in selected patients than with sorafenib only. In our study, when liver resection was combined with sorafenib, there was significantly better OS than for liver resection alone. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate adjuvant sorafenib for BCLC-stage C patients after curative resection. Adjuvant systemic treatment is the most promising of all adjuvant therapies for locally advanced HCC, as this disease is likely to be systemic at this stage.

Table 5.

Comparison of outcomes of patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage C hepatocellular carcinoma treated by various interventions

| Study | Year | Number of patients | Interventions | Median OS, mo | 1-, 3-, 5-yr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFS, % | OS, % | |||||

| Llovet et al[9] | 2008 | 299 | Sorafenib | 10.7 | - | 44/-/-1 |

| 303 | Placebo | 7.9 | - | 33/-/- | ||

| Cheng et al[22] | 2009 | 150 | Sorafenib | 6.5 | - | 53.3/-/-1 |

| 76 | Placebo | 4.2 | - | 36.7/-/-1 | ||

| Wörns et al[23] | 2009 | 22 | Sorafenib | 3.3 | - | - |

| Yau et al[24] | 2009 | 51 | Sorafenib | 5.0 | - | - |

| Ozenne et al[25] | 2010 | 50 | Sorafenib | 5.5 | - | - |

| Baek et al[26] | 2011 | 201 | Sorafenib | 5.3 | - | - |

| Iavarone et al[27] | 2011 | 296 | Sorafenib | 10.51 | ||

| Santini et al[28] | 2012 | 93 | Sorafenib | 12.01 | ||

| Zhao et al[29] | 2013 | 222 | Sorafenib and TACE | 12.01 | ||

| Minagawa et al[30] | 2001 | 18 | Liver resection | 82/42/42 | ||

| Chirica et al[31] | 2008 | 20 | Liver resection | 32.0 | 40/20/171 | 73/56/451 |

| Ishizawa et al[32] | 2008 | 98 | Liver resection | -/37/25 | -/71/56 | |

| Wang et al[33] | 2008 | 14 | Liver resection | 13.0 | 57/29/29 | |

| Torzilli et al[34] | 2008 | 28 | Liver resection | 66/17/- | 80/74/- | |

| Yang et al[35] | 2012 | 511 | Liver resection | 27.8 | 48/30/24 | 70/41/31 |

| Torzilli et al[10] | 2013 | 297 | Liver resection | 46/28/18 | 76/49/38 | |

| This study | 2014 | 68 | Liver resection | 18.0 | 42/26/- | 69/34/- |

| 34 | Liver resection and Sorafenib | 25.0 | 63/37/- | 88/53/- |

PET/CT was used for the diagnosis of extrahepatic metastasis in this study, as 18F-FDG PET/CT is currently the most sophisticated technique to detect metastases, despite the possibility of false positivity. A systematic review and meta-analysis published recently reported the pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of metastatic HCC were 76.6%, 98.0%, 14.68 and 0.28, respectively[21]. This study has the limitations of small case number and the study came from a single institute; also, the median follow-up was not long enough. As a retrospective study, the selection bias was fully considered and treated by matching and statistic analysis. Future prospective clinical randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm our results.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the safety and potential benefits of sorafenib in both decreasing the incidence of HCC recurrence and extending the DFS and OS rates for patients with locally advanced HCC after curative resection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Miss Shu Chen, a research assistant, for her help with data collection and statistical analyses.

COMMENTS

Background

To investigate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant sorafenib after potentially curative resection for patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer-stage C hepatocellular carcinoma (BCLC-stage C HCC).

Research frontiers

Hepatocarcinogenesis is a complex process including many signaling cascades. Currently, there is no standard of care for adjuvant therapy because no treatment has a proven benefit in randomized studies in patients with HCC after potentially curative treatment. Sorafenib is approved for use in patients with unresectable HCC based on two phase 3 randomized trials, and is the recommended treatment in patients with advanced HCC. Animal studies and a few retrospective clinical studies published recently have indicated sorafenib inhibited tumor growth and prevented tumor recurrence after resection of HCC.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Based on the mechanism of sorafenib, inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, in addition to it’s proven efficacy in advanced HCC, there is rationale for the study of sorafenib as an adjuvant therapy in HCC.

Applications

It is worthwhile to investigate the efficacy of adjuvant sorafenib after potentially curative resection for BCLC-stage C HCC patients with the prospective clinical randomized controlled trials in future.

Terminology

Thirty-four HCC patients received adjuvant sorafenib after curative liver resection and were compared with a case-matched control group of 68 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy.

Peer-review

This case-control study proves the important clinical role of sorafenib as an adjuvant treatment after R0 resection of BCLC-stage C HCC patients. It would be worth using sorafenib not just in advanced but in early stages of HCC.

Footnotes

Supported by Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and Pathology of Ministry of Education No. 2012jsz108; and the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China No. 81272224.

Institutional review board statement: This study was carried out with pre-approval given by the Ethics Committee of the Southwest Hospital, in accordance with its conformation to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for their data to be used for research purposes.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: March 7, 2016

First decision: March 21, 2016

Article in press: April 20, 2016

P- Reviewer: Al-Shamma S, Sipos F, Skok P S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Matsuda K. Novel susceptibility loci for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic HBV carriers. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2012;1:59–60. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2012.10.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–2576. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee KH, Wu CJ, Wang CC, Hung JH. Prevention of chronic HBV infection induced hepatocellular carcinoma development by using antiplatelet drugs. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2012;1:57–58. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2012.10.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morise Z, Kawabe N, Tomishige H, Nagata H, Kawase J, Arakawa S, Yoshida R, Isetani M. Recent advances in the surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14381–14392. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavien PA, Petrowsky H, DeOliveira ML, Graf R. Strategies for safer liver surgery and partial liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1545–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra065156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M, et al. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:929–937. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828329b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He VJ. Professor Pierce Chow: neo-adjuvant and adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma-current evidence. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013;2:239–241. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2013.07.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng YX, Wang T, Deng YZ, Yang P, Li JJ, Guan DX, Yao F, Zhu YQ, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Sorafenib suppresses postsurgical recurrence and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in an orthotopic mouse model. Hepatology. 2011;53:483–492. doi: 10.1002/hep.24075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saab S, McTigue M, Finn RS, Busuttil RW. Sorafenib as adjuvant therapy for high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma in liver transplant recipients: feasibility and efficacy. Exp Clin Transplant. 2010;8:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia F, Lau WY, Xu Y, Wu L, Qian C, Bie P. Does hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury induced by hepatic pedicle clamping affect survival after partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma? World J Surg. 2013;37:192–201. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urata K, Hashikura Y, Ikegami T, Terada M, Kawasaki S. Standard liver volume in adults. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:2093–2094. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, Langer C, Murphy B, Cumberlin R, Coleman CN, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Hu J, Qiu SJ, Huang XW, Dai Z, Tan CJ, Zhou J, Fan J. An investigation of the effect of sorafenib on tumour growth and recurrence after liver cancer resection in nude mice independent of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase levels. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:1039–1045. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.588598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SN, Chuang SC, Lee KT. Efficacy of sorafenib as adjuvant therapy to prevent early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgery: A pilot study. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:523–531. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, Cai J, Poon RT, Han KH, Tak WY, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Hu P, Chen X, Bie P. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib versus TACE for intermediate or advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin CY, Chen JH, Liang JA, Lin CC, Jeng LB, Kao CH. 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT for detecting extrahepatic metastases or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2417–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wörns MA, Weinmann A, Pfingst K, Schulte-Sasse C, Messow CM, Schulze-Bergkamen H, Teufel A, Schuchmann M, Kanzler S, Düber C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in consideration of concomitant stage of liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:489–495. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818ddfc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yau T, Chan P, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Fan ST, Poon RT. Phase 2 open-label study of single-agent sorafenib in treating advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in a hepatitis B-endemic Asian population: presence of lung metastasis predicts poor response. Cancer. 2009;115:428–436. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozenne V, Paradis V, Pernot S, Castelnau C, Vullierme MP, Bouattour M, Valla D, Farges O, Degos F. Tolerance and outcome of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1106–1110. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283386053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baek KK, Kim JH, Uhm JE, Park SH, Lee J, Park JO, Park YS, Kang WK, Lim HY. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib: a retrospective comparison with previously known prognostic models. Oncology. 2011;80:167–174. doi: 10.1159/000327591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iavarone M, Cabibbo G, Piscaglia F, Zavaglia C, Grieco A, Villa E, Cammà C, Colombo M. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology. 2011;54:2055–2063. doi: 10.1002/hep.24644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santini D, Addeo R, Vincenzi B, Calvieri A, Montella L, Silletta M, Caraglia M, Vespasiani U, Picardi A, Del Prete S, et al. Exploring the efficacy and safety of single-agent sorafenib in a cohort of Italian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:1283–1288. doi: 10.1586/era.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Wang WJ, Guan S, Li HL, Xu RC, Wu JB, Liu JS, Li HP, Bai W, Yin ZX, et al. Sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale multicenter study of 222 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1786–1792. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Ohtomo K. Selection criteria for hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus. Ann Surg. 2001;233:379–384. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chirica M, Scatton O, Massault PP, Aloia T, Randone B, Dousset B, Legmann P, Soubrane O. Treatment of stage IVA hepatocellular carcinoma: should we reappraise the role of surgery? Arch Surg. 2008;143:538–543; discussion 543. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Aoki T, Takahashi M, Inoue Y, Sano K, Imamura H, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Neither multiple tumors nor portal hypertension are surgical contraindications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1908–1916. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JH, Changchien CS, Hu TH, Lee CM, Kee KM, Lin CY, Chen CL, Chen TY, Huang YJ, Lu SN. The efficacy of treatment schedules according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging for hepatocellular carcinoma - Survival analysis of 3892 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1000–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torzilli G, Donadon M, Marconi M, Palmisano A, Del Fabbro D, Spinelli A, Botea F, Montorsi M. Hepatectomy for stage B and stage C hepatocellular carcinoma in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer classification: results of a prospective analysis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1082–1090. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang T, Lin C, Zhai J, Shi S, Zhu M, Zhu N, Lu JH, Yang GS, Wu MC. Surgical resection for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1121–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]