Phase 3 study of dasatinib 140 mg once daily versus 70 mg twice daily in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase resistant or intolerant to imatinib: 15-month median follow-up (original) (raw)

Abstract

Dasatinib is the most potent BCR-ABL inhibitor, with 325-fold higher potency than imatinib against unmutated BCR-ABL in vitro. Studies have demonstrated the benefits of dasatinib 70 mg twice daily in patients with accelerated-phase chronic myeloid leukemia intolerant or resistant to imatinib. A phase 3 study compared the efficacy and safety of dasatinib 140 mg once daily with the current twice-daily regimen. Here, results from the subgroup with accelerated-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (n = 317) with a median follow-up of 15 months (treatment duration, 0.03-31.15 months) are reported. Among patients randomized to once-daily (n = 158) or twice-daily (n = 159) treatment, rates of major hematologic and cytogenetic responses were comparable (major hematologic response, 66% vs 68%; major cytogenetic response, 39% vs 43%, respectively). Estimated progression-free survival rates at 24 months were 51% and 55%, whereas overall survival rates were 63% versus 72%. Once-daily treatment was associated with an improved safety profile. In particular, significantly fewer patients in the once-daily group experienced a pleural effusion (all grades, 20% vs 39% P < .001). These results demonstrate that dasatinib 140 mg once daily has similar efficacy to dasatinib 70 mg twice daily but with an improved safety profile. This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #CA180-035.

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is characterized by a triphasic natural course comprising a chronic phase (CP), typically followed by an accelerated phase (AP), and finally a blast phase (BP).1,2 Approximately two-thirds of patients progress to BP via AP with a median survival for patients in AP of 1 to 2 years.1,3 Although the mechanisms behind progression to advanced phase disease in CML have not been fully elucidated, several processes may play a role, including additional cytogenetic abnormalities (clonal evolution), genetic mutations and deletions, and up-regulation of specific genes.3–6

Current first-line therapy for AP-CML is imatinib mesylate (Glivec [in the United States, Gleevec]; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor of BCR-ABL.7–9 Although imatinib induces notable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with accelerated-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML-AP), these responses are frequently short-lived, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 8.8 months.7 Development of resistance to imatinib represents an important clinical issue affecting approximately 50% of patients with CML-AP within 2 years of treatment.10 Because progression on imatinib is associated with poor prognosis,11 alternative treatment options are required.

Dasatinib (SPRYCEL; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Stamford, CT) was the first agent approved to overcome the problems of imatinib therapy in patients with CML. Dasatinib is structurally unrelated to imatinib and is approximately 325-fold more potent than imatinib at inhibiting unmutated BCR-ABL in vitro.12 Preclinical studies have also shown that dasatinib has potent activity against other kinases, including Src family kinases.13,14 An extensive phase 2 program confirmed the efficacy and safety of dasatinib 70 mg twice daily in all phases of CML or Philadelphia chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).15–19 Data from a phase 1 dose-escalation study showed that treatment with dasatinib 140 mg once daily was also associated with significant hematologic and cytogenetic responses, and with longer-term follow-up; this regimen has been found to result in a lower incidence of pleural effusion than twice-daily dosing.20 It was therefore decided to further evaluate dasatinib dosing schedules in larger clinical trials. The aim of the current phase 3 study was to assess dasatinib 140 mg once daily and 70 mg twice daily in patients resistant or intolerant to imatinib with CML-AP. Here, we report data from 2 years of follow-up of patients with CML-AP.

Methods

Study design and patient eligibility

This was a randomized, 2-arm, multicenter, open-label, phase 3 trial evaluating dasatinib 140 mg daily dose (administered on either a 140 mg once-daily or 70 mg twice-daily schedule) in patients 18 years of age or older with AP-CML, BP-CML, or Ph+ ALL. This report focuses on the subgroup of patients with AP-CML.

Inclusion criteria required that all patients had stopped treatment with imatinib after resistance or intolerance. Resistance to imatinib was defined as no hematologic response (HR) to imatinib after at least 4 weeks of treatment or an increase of 50% or more in peripheral blood blasts after 2 weeks of treatment with at least 600 mg/day; achieved HR and subsequently no longer met the criteria consistently on all assessments over a consecutive 2-week period while receiving imatinib (≥ 600 mg/day); or patients initially diagnosed with CML-CP who progressed to CML-AP while receiving imatinib at any dose. Intolerance to imatinib was defined as having grade 3 or greater nonhematologic toxicity or grade 4 or greater hematologic toxicity lasting for more than 2 weeks while on imatinib at least 600 mg/day that led to discontinuation of therapy, or to dose decrease to 400 mg/day or less with loss of HR. In addition, all patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 to 2 and adequate hepatic and renal function. To meet inclusion criteria for CML-AP, patients were required to have peripheral blood or bone marrow counts of at least 15% but less than 30% blasts, blasts plus promyelocytes at least 30% but less than 30% blasts alone, at least 20% basophils, and platelet counts less than 100 × 109/L unrelated to drug therapy. Patients with clonal evolution or with prior CML-AP (except those defined by elevated basophil count only) who achieved an HR and subsequently progressed were included even if they did not reach the threshold values of percentage of blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow for AP. Exclusion criteria included: treatment with imatinib, interferon-α, cytarabine, or any targeted small molecule anticancer agent within 7 days of initiation; uncontrolled or significant cardiovascular disease; history of a significant bleeding disorder unrelated to CML; or any concurrent incurable malignancy other than CML. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient before participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by local ethics committees/institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Randomization was stratified by phase and type of disease and imatinib status (resistant or intolerant).

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of dasatinib 140 mg once daily and dasatinib 70 mg twice daily in terms of best confirmed major HR. Other secondary endpoints included evaluation of overall HR, cytogenetic response (CyR), time to and duration of responses, PFS, overall survival (OS), and safety.

Treatment with dasatinib

Dasatinib was administered orally either as 140 mg once daily or 70 mg twice daily. Dose escalation to 180 mg once daily or 90 mg twice daily was allowed for inadequate response (rising percentage of blasts or loss of HR in 2 consecutive assessments at least one week apart; absence of a complete HR [CHR], no evidence of leukemia [NEL], or minor HR within 4 weeks; no major CyR [MCyR] after 3 months; or no complete CyR [CCyR] after 6 months). Dose interruption or reduction to 80 mg once daily or 40 mg twice daily was allowed in cases of drug toxicity (grade 2 or greater nonhematologic toxicity considered related to dasatinib; absolute neutrophil count < 0.5 × 109/L and/or platelets < 10 × 109/L for more than 6 weeks with bone marrow cellularity < 10% with blasts < 5% or bone marrow cellularity > 10% with blasts > 5%; or febrile neutropenia with signs of septicemia).

CML therapies other than dasatinib were prohibited during the study, with the exception of hydroxyurea for elevated white blood cell counts. Colony-stimulating factors and recombinant erythropoietin were permitted at the discretion of the investigator, according to institutional guidelines. Patients were supported with platelet transfusions as required.

Patient evaluation

Hematologic assessment (defined previously17) was performed on all patients within 72 hours of initiating treatment, weekly during weeks 1 through 6, at weeks 8 and 12, and monthly thereafter. Major HR was defined as attaining a CHR or NEL (normalization of peripheral blood counts, white blood cell count less than 10 × 109/L, platelets from 20 to less than 100 × 109/L absolute neutrophil count 0.5 to less than 1.0 × 109/L). A CHR was confirmed if all criteria were met consistently for subsequent assessments for at least 28 days. During this interval, 2 consecutive assessments showing nonresponse were interpreted as response not achieved, whereas a single nonresponse between 2 assessments qualifying for CHR did not preclude a response being achieved.

Disease progression was defined by the first occurrence after administration of maximum dasatinib dose of any of the following: initial HR but subsequent failure to consistently meet HR criteria over a consecutive 2-week period; no decrease from on-study baseline for percentage blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow on all assessments over a 4-week period; absolute increase of at least 50% in peripheral blood blasts over a 2-week period; development of CML-BP at any time after initiation of therapy; or development of extramedullary disease sites other than the spleen or liver. Patients who died without progressing were considered to have progressed at the time of death.

Cytogenetic assessment of bone marrow metaphases was performed within 4 weeks and subsequently at the end of months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12. Standard definitions of CyR were used: CCyR, 0% Ph+ metaphases; partial CyR (PCyR), more than 0% to 35% Ph+ metaphases; minor CyR, 36% to 65% Ph+ metaphases; minimal CyR, more than 65% to 95% Ph+ metaphases; and no CyR, more than 95% Ph+ metaphases. An MCyR was defined as either a CCyR or PCyR.

BCR-ABL mutation data were collected by DNA sequencing at baseline and at the end of treatment.

Safety and tolerability were assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Statistical analyses

No formal statistical comparison between treatment arms was planned for CA180-035 subgroup analyses. Exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by Clopper and Pearson were calculated for estimates of major HR and MCyR.21 PFS, OS, and time to and duration of major HR and MCyR were estimated using Kaplan-Meier product limit methodology, and median and 95% CI values22 were calculated. Across the entire CA180-035 study (including CML-AP in addition to other patient subgroups), the noninferiority of once-daily compared with twice-daily treatment for the primary endpoint was based on whether the lower bound of the 95% CI for the difference in major HR rates at 6 months between the regimens was more than or equal to 2%. For descriptive purposes, post-hoc analyses were performed using log-rank test (PFS and OS) and Fisher exact test.

Selected adverse event rates (pleural effusion, gastrointestinal bleeding, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, white blood cell, platelet, absolute neutrophil count) were compared using Fisher exact test (all Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grades).

Results

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

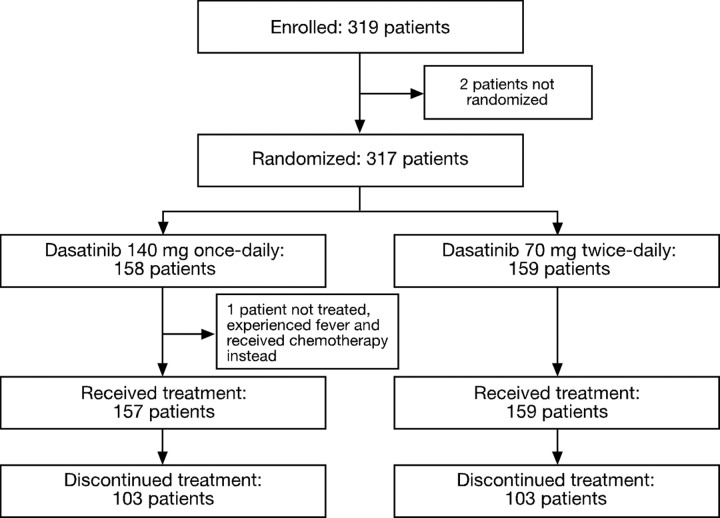

In total, 319 patients with CML-AP from 97 centers worldwide were enrolled in this study between July 2005 and March 2006. Of these, 317 patients were randomized to dasatinib 140 mg once daily or 70 mg twice daily (Figure 1). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were representative of patients with CML-AP and were comparable between the 2 treatment schedules (Table 1). Three patients were enrolled in the once-daily group who were Ph− and BCR-ABL+. Among the 316 patients who received at least one dose of study drug, the median duration of therapy was 15.4 months (range, 0.03-31.15 months) in the once-daily group and 12 months (range, 0.39-28.8 months) in the twice-daily group. At last follow-up, 110 patients were still receiving on-study dasatinib treatment. Results are reported with follow-up extending to 34.5 months (minimum, 0.16 months; median follow-up, 15 months; median duration of treatment all subjects, 13.6 months).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for the CA180-035 study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of all randomized patients

| Characteristic | 140 mg once daily (n = 158) | 70 mg twice daily (n = 159) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 56.0 (17.0-81.0) | 56.0 (19.0-84.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 88 (56) | 94 (59) |

| Median disease duration, mo (range) | 74.3 (5.1-326.8) | 70.1 (2.5-199.7) |

| Prior imatinib > 600 mg/day, n (%) | 68 (43) | 73 (46) |

| Prior imatinib duration | ||

| Less than 1 year, n (%) | 23 (15) | 24 (15) |

| 1-3 years, n (%) | 51 (32) | 54 (34) |

| More than 3 years, n (%) | 84 (53) | 80 (50) |

| Best response before imatinib failure, n (%) | ||

| CHR | 121 (77) | 119 (75) |

| MCyR | 48 (30) | 44 (28) |

| Imatinib status, n (%) | ||

| Resistant | 117 (74) | 116 (73) |

| Intolerant | 41 (26) | 43 (27) |

| BCR-ABL mutation detected, no. (%) | 66/141 (47) | 70/151 (46) |

| T315I mutation detected, n (%) | 11/141 (8) | 9/151 (6) |

| Other prior therapy, n (%) | ||

| Interferon-α | 85 (54) | 87 (55) |

| Chemotherapy | 70 (44) | 70 (44) |

| Stem cell transplantation | 19 (12) | 9 (6) |

| Response status, n (%) | ||

| Patients in CHR at entry | 16 (10) | 31 (19) |

| Patients in MCyR at entry | 15 (9) | 12 (8) |

| Patients in CCyR at entry | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| ECOG performance status 0 or 1 | 148 (94) | 143 (90) |

Hematologic and cytogenetic responses

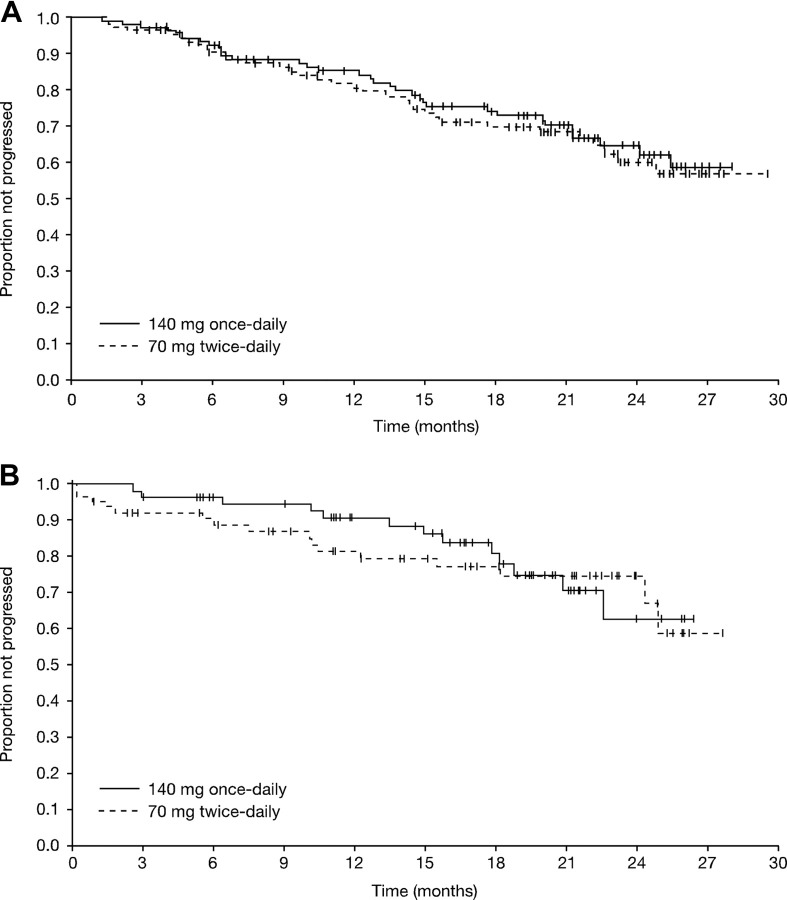

Hematologic and cytogenetic response rates were similar with the 2 dasatinib dosing schedules (Table 2). Major HRs were achieved in 66% of patients in the once-daily group (95% CI, 59%-74%) and 68% of patients in the twice-daily group (95% CI, 60%-75%), including CHRs in 47% (95% CI, 40%-56%) and 52% (95% CI, 44%-60%) of patients on once- and twice-daily dosing, respectively. Most major HRs were achieved within 4 months of therapy, and the median time to major HR was 1.9 months in both treatment groups. Among patients achieving a major HR, the median duration of response was not reached in either treatment group at the time of the data analysis (Figure 2). Among responding patients in the once-daily and twice-daily groups, a major HR was sustained for 12 months by an estimated 85% versus 82% of patients, and for 24 months by 65% versus 60%, respectively. Of 47 patients entering with a CHR at baseline, CHRs were maintained in 35 patients (74%, imatinib-resistant, 21 of 28; imatinib-intolerant, 14 of 19). CHR was achieved in 45% of patients (122 of 270) with no CHR at baseline (imatinib-resistant, 97 of 205; imatinib-intolerant, 25 of 65).

Table 2.

Treatment response of all randomized patients

| 140 mg once daily (n = 158) | 70 mg twice daily (n = 159) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |

| Hematologic response | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 119/158 | 75 (67.8-81.8) | 120/159 | 76 (68.0-81.9) |

| Imatinib-resistant | 83/117 | 71 | 86/116 | 74 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 36/41 | 88 | 34/43 | 79 |

| MHR | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 105/158 | 66 (58.5-73.8) | 108/159 | 68 (60.1-75.1) |

| Without MHR at baseline | 78/129 | 60 | 73/118 | 62 |

| Imatinib-resistant | 74/117 | 63 | 79/116 | 68 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 31/41 | 76 | 29/43 | 67 |

| CHR | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 75/158 | 47 (39.5-55.6) | 82/159 | 52 (43.5-59.6) |

| Without CHR at baseline | 63/142 | 44 | 59/128 | 46 |

| Imatinib-resistant | 59/117 | 50 | 59/116 | 51 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 16/41 | 39 | 23/43 | 53 |

| NEL | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 30/158 | 19 (13.2-26.0) | 26/159 | 16 (11.0-23.0) |

| Imatinib-resistant | 15/117 | 13 | 20/116 | 17 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 15/41 | 37 | 6/43 | 14 |

| MCyR | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 61/158 | 39 (31.0-46.7) | 68/159 | 43 (35.0-50.8) |

| Without MCyR at baseline | 48/143 | 34 | 57/147 | 39 |

| Excluding Ph− patients | 59/155 | 38 | 68/159 | 43 |

| Imatinib-resistant | 42/117 | 36 | 49/116 | 42 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 19/41 | 46 | 19/43 | 44 |

| CCyR | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 51/158 | 32 (25.1-40.2) | 52/159 | 33 (25.5-40.6) |

| Without CCyR at baseline | 51/157 | 32 | 49/156 | 31 |

| Excluding Ph− patients | 49/155 | 32 | 52/159 | 33 |

| Imatinib-resistant | 34/117 | 29 | 38/116 | 33 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 17/41 | 41 | 14/43 | 33 |

| PCyR | ||||

| Overall (95% CI) | 10/158 | 6 (3.1-11.3) | 16/159 | 10 (5.9-15.8) |

| Imatinib-resistant | 8/117 | 7 | 11/116 | 10 |

| Imatinib-intolerant | 2/41 | 5 | 5/43 | 12 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analyses of duration. (A) Major hematologic response. (B) Major cytogenetic response.

Overall, the MCyR rate was 39% (95% CI, 31%-47%) in the once-daily group and 43% (95% CI, 35%-51%) in the twice-daily group. CCyR rates were 32% and 33%, respectively. The median time to MCyR was 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.1-5.6 months) in the once-daily group and 2.5 months (95% CI, 1.9-3.0 months) in the twice-daily group, with most MCyRs being achieved within 6 months. Among patients achieving an MCyR, the median duration of response was not reached in either treatment group at the time of data analysis (Figure 2). Among responding patients in the once-daily and twice-daily groups, an MCyR was sustained for 12 months by 91% versus 82% of patients, and for 24 months by 63% versus 75%, respectively. Of 27 patients entering with an MCyR at baseline, MCyRs were maintained in 24 patients (89%, imatinib-resistant, 12 of 14; imatinib-intolerant, 12 of 13). MCyR was achieved in 36% of patients (105 of 290) with no MCyR at baseline (imatinib-resistant, 79 of 219; imatinib-intolerant, 26 of 71). Excluding the 3 patients on once-daily treatment that were Ph−, the MCyR and CCyR rates were 38% and 43%, and 32% and 33% in the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively.

BCR-ABL mutations

According to mutation status, major HR and MCyR rates with dasatinib were broadly similar between treatment groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responses by baseline BCR-ABL mutation

| 140 mg once daily, n = 158 | 70 mg twice daily, n = 159 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. response/total | % response | No. response/total | % response | |

| MaHR | ||||

| No BCR-ABL mutation* | 51/75 | 68 | 56/81 | 69 |

| Any BCR-ABL mutation | 43/66 | 65 | 46/70 | 66 |

| Excluding T315I mutation | 41/55 | 75 | 44/61 | 72 |

| MCyR | ||||

| No BCR-ABL mutation* | 33/75 | 44 | 33/81 | 41 |

| Any BCR-ABL mutation | 18/66 | 27 | 29/70 | 41 |

| Excluding T315I mutation | 18/55 | 33 | 29/61 | 48 |

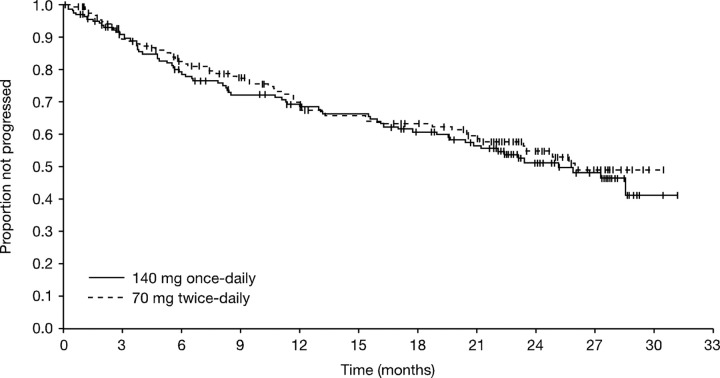

PFS

The treatment groups were comparable in terms of the proportion of patients sustaining a PFS during follow-up (Figure 3). The median PFS was 25.1 and 26.0 months for the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively. Estimated PFS rates were 68% (95% CI, 61%-76%) and 69% (95% CI, 61%-77%) at 12 months, and 51% (95% CI, 42%-60%) and 55% (95% CI, 46%-64%) (P = .566) at 24 months for the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively. Excluding patients with a T315I mutation, 24-month PFS rates were 52% (95% CI, 43%-61%) and 57% (95% CI, 48%-66%). Excluding patients who were in CHR at baseline, 24-month PFS rates were and 45% (95% CI, 36%-55%) and 52% (95% CI, 42%-62%) for the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival (all randomized patients).

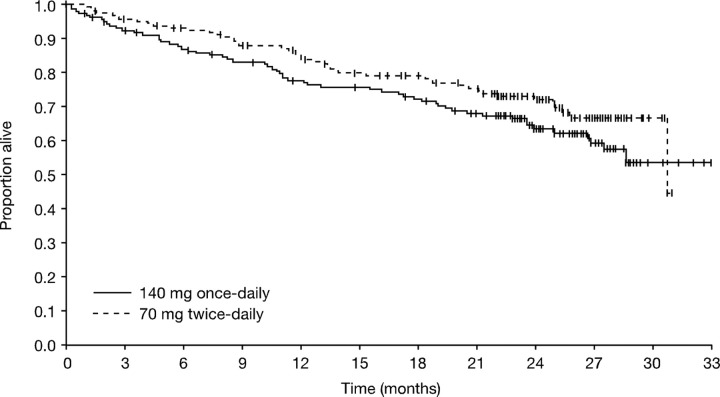

OS

The median OS was not reached for the once-daily group and 30.7 months for the twice-daily group (Figure 4). For the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively, estimated OS rates were 78% (95% CI, 71%-84%) and 84% (95% CI, 79%-90%) at 12 months, and 63% (95% CI, 56%-71%) and 72% (95% CI, 65%-79%) at 24 months (P = .140). Among patients who died during the study, a similar number of patients died of progressive disease in the 2 treatment groups (52% vs 43%, respectively; P = .435). Other reasons for death in the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively, assigned by study investigators, were: cardiovascular disease (2% vs 11%; P = .085), fatal bleeding (7% vs 9%), infection (22% vs 24%), other (9% [including a combination of disease plus sepsis, cardiac arrest, acute respiratory failure, sudden death, and acute respiratory distress syndrome] vs 11% [including 2 cases of graft-versus-host disease after transplant, cerebrovascular accident, status epilepticus, and respiratory arrest]), study drug toxicity (2% vs 0%), and unknown (7% vs < 2%).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (all randomized patients).

At 24 months, the estimated OS rate in the once- and twice-daily groups was 64% and 76% for those patients with no BCR-ABL mutation, 64% and 73% for those patients with any mutation excluding T315I, and 62% and 67% for those with any mutation including T315I.

Safety and tolerability

Both dasatinib schedules were relatively well tolerated during the course of the study. Nonhematologic adverse events were generally mild to moderate (grades 1 or 2). The incidence of individual grade 3 to 4 events was less than or equal to 8% (Table 4). Diarrhea, fluid retention, nausea, headache, and fatigue were the most common all-grade nonhematologic adverse events. Rates of nonhematologic adverse events were similar between the 2 groups, although a trend was observed for a lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding with once-daily versus twice-daily treatment (all grades, 8% vs 13%, respectively P = .2036). Compared with 70 mg twice daily, 140 mg once daily was associated with a lower incidence of all-grade fluid retention–related events. In particular patients, receiving once-daily treatment had significantly fewer pleural effusions (all grades, 20% vs 39%, P < .001; Table 4). Pleural effusions were manageable and led to treatment discontinuation in only 4% (once-daily group) and 9% (twice-daily group) of patients. Pericardial effusions occurred slightly more frequently in the twice-daily group (once-daily vs twice-daily: all grades, 3% vs 7%; grade 3 to 4, 1% vs 3%). The incidence of congestive heart failure or cardiac dysfunction was 0% and 3% in the once- and twice-daily groups, respectively. As would be expected for patients with advanced-stage disease, the incidence of all-grade cytopenia was high and was comparable between the 2 groups.

Table 4.

Adverse events associated with dasatinib (all treated patients)

| 140 mg once daily (N = 157) | 70 mg twice daily (N = 159) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade 3 or 4 | All grades | Grade 3 or 4 | |

| Nonhematologic adverse events,* n (%) | ||||

| Diarrhea | 49 (31) | 4 (3) | 50 (31) | 5 (3) |

| Fluid retention | 53 (34) | 12 (8) | 77 (48) | 17 (11) |

| Pleural effusion† | 31 (20) | 11 (7) | 62 (39) | 10 (6) |

| Superficial edema | 28 (18) | 1 (1) | 32 (20) | 0 |

| Other fluid retention | 7 (4) | 2 (1) | 24 (15) | 8 (5) |

| Nausea | 30 (19) | 1 (1) | 28 (18) | 3 (2) |

| Headache | 43 (27) | 2 (1) | 37 (23) | 1 (1) |

| Fatigue | 30 (19) | 3 (2) | 32 (20) | 5 (3) |

| Vomiting | 18 (11) | 1 (1) | 24 (15) | 2 (1) |

| Pyrexia | 18 (11) | 3 (2) | 18 (11) | 2 (1) |

| Dyspnea | 32 (20) | 5 (3) | 37 (23) | 11 (7) |

| Hemorrhage | 41 (26) | 13 (8) | 48 (30) | 11 (7) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 13 (8) | 9 (6) | 21 (13) | 10 (6) |

| Other | 30 (19) | 3 (2) | 33 (21) | 2 (1) |

| Cough | 12 (8) | 0 | 18 (11) | 0 |

| Rash | 23 (15) | 0 | 29 (18) | 1 (1) |

| Myalgia | 11 (7) | 1 (1) | 21 (13) | 3 (2) |

| Arthralgia | 15 (10) | 0 | 13 (8) | 2 (1) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 18 (11) | 0 | 23 (14) | 3 (2) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 16 (10) | 16 (10) |

| Infection‡ | 16 (10) | 9 (6) | 17 (11) | 3 (2) |

| Cytopenia | ||||

| Anemia | 154/155 (99) | 74/155 (48) | 158/159 (99) | 68/159 (43) |

| Leukopenia | 127/155 (82) | 69/155 (45) | 136/159 (86) | 65/159 (41) |

| Neutropenia | 130/155 (84) | 91/155 (59) | 141/159 (89) | 109/159 (69) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 137/155 (88) | 99/155 (64) | 148/159 (93) | 107/159 (67) |

Dose adjustments and treatment discontinuations

The once-daily group required fewer dose reductions (38% vs 50%) and interruptions (64% vs 74%) than the twice-daily group (Table 5). For both schedules, nonhematologic toxicity was the main reason for dose interruption and/or reduction. Dasatinib dose was escalated in a higher proportion of once-daily recipients (33% vs 25%).

Table 5.

Dose adjustments and treatment discontinuations

| 140 mg once daily (N = 157) | 70 mg twice daily (N = 159) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median daily dose, mg (range) | 138.0 (20.0-216.0) | 110.0 (20.0-178.0) |

| Interruption, n (%) | ||

| Hematologic toxicity | 40 (25) | 47 (30) |

| Nonhematologic toxicity | 48 (31) | 61 (38) |

| Reduction, n (%) | ||

| Hematologic toxicity | 29 (18) | 30 (19) |

| Nonhematologic toxicity | 27 (17) | 44 (28) |

| Escalation, n (%) | 52 (33) | 39 (25) |

| Still on therapy, n (%) | 54 (34) | 56 (35) |

| Discontinued therapy, n (%) | ||

| Disease progression | 39 (25) | 32 (20) |

| Study drug toxicity | 32 (20) | 39 (25) |

| Adverse event unrelated to study drug | 9 (6) | 7 (4) |

| Investigator request | 6 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Patient request | 4 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Proceeding to stem cell transplantation | 2 (1) | 9 (6) |

| Lack or loss of response | 6 (4) | 2 (1) |

| Anemia/thrombocytopenia | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

| Death | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

| Development of mutation | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Protocol violation | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

| Poor compliance | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

| Pregnancy | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) |

At the time of analysis, 34% of patients in the once-daily group and 35% of patients in the twice-daily group remained on study, with a median duration of therapy of 23 months in both treatment arms.

Discussion

In the current study, dasatinib 140 mg once daily was associated with comparable hematologic and cytogenetic response rates to the standard 70-mg twice-daily regimen. A similar proportion of patients in both groups had sustained a durable response at 24 months. The PFS rate was also similar between both groups. Estimated OS rates showed that 60% to 70% of patients were alive with 15 months of follow-up. Compared with the earlier analysis of data from 6.5 months of follow up,23 response rates were increased (once daily vs twice daily: major HR from 63% to 66% vs 66% to 68%; CCyR from 27% to 32% vs 27% to 33%).

Although dasatinib was generally well tolerated with both dose schedules, once-daily treatment was associated with an improved safety profile compared with twice-daily treatment. The proportions of patients remaining on study at last follow-up were similar in each treatment group. Adverse events of special interest that have been previously described with dasatinib and other Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors include cytopenia, fluid retention, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Compared with twice-daily treatment, once-daily dasatinib therapy was associated with a significantly lower incidence of pleural effusion (P < .001). A trend was also seen toward lower rates of all-grade gastrointestinal bleeding in the once-daily group. In a recent phase 3 dose- and schedule-optimization study conducted in patients with CML-CP a tolerability benefit in favor of once-daily dosing was also reported.24

The results presented here are consistent with longer-term results from the phase 2 study of dasatinib 70 mg twice daily in 174 patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant CML-AP (median follow-up, 14.1 months).25 A total of 64% of patients achieved a major HR, and 39% and 32% of patients achieved an MCyR and CCyR, respectively.

Sustained efficacy and improved tolerability for a once-daily compared with a twice-daily dasatinib regimen have also been reported among patients with CML-CP resistant or intolerant to imatinib.24 The authors speculated that the noncontinuous target inhibition with once-daily dosing may explain these observations. After administration, dasatinib is extensively metabolized, with an elimination half-life of less than 4 hours.26 In a study of patients enrolled in a phase 1 trial, levels of phosphorylated CrkL, a marker for Bcr-Abl activity, decreased in a dose-dependent manner 4 hours after an initial dose of dasatinib.27 As dasatinib serum levels declined, CrkL phosphorylation was restored, indicating that once-daily dosing resulted in transient Bcr-Abl inhibition.27 In vitro studies showed that transient inhibition of CrkL phosphorylation, induced by dasatinib at clinically relevant concentrations, resulted in the rapid death of CML cells.27 These data suggest that continuous Bcr-Abl exposure may not be required for efficacy. The safety benefits of once-daily dasatinib treatment have been examined in a recent pharmacokinetic analysis in patients with CML-CP.28 Dasatinib administered as 140 mg once daily or 70 mg twice daily resulted in similar plasma steady-state average concentrations, but the plasma steady-state trough concentration (Cmin) was lower with 140 mg once daily. Importantly, Cmin levels correlated with dasatinib safety parameters.

The efficacy of another Bcr-Abl inhibitor, nilotinib (Tasigna, Novartis), has recently been evaluated in CML-AP.29 In an open-label, phase 2 study among 136 patients (median treatment duration, 210 days), a confirmed HR was achieved in 54% (69 of 129) with 34 patients (26%) achieving a CHR. Major CyR was achieved by 40 patients (31%) with 24 patients (19%) achieving a CCyR. At 12 months, the estimated PFS and OS rates were 57% and 81%, respectively. The most common grade 3 or 4 hematologic adverse events were thrombocytopenia (41%), neutropenia (39%), anemia (25%), and elevated serum lipase (16%). Although dasatinib has been shown to be 16-fold more potent than nilotinib at inhibiting unmutated BCR-ABL in vitro,30 no direct comparisons between these agents in the CML setting have so far been reported.

In conclusion, the extended follow-up from this study demonstrates that dasatinib 140 mg once daily has similar efficacy to dasatinib 70 mg twice daily but with an improved safety profile. For patients with CML-AP who are resistant or intolerant to imatinib, a dasatinib dose of 140 mg once daily is recommended.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Editorial and writing support was provided by Gardiner-Caldwell US, funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

In addition to the authors, the following primary investigators also participated in this trial: Argentina: E. O. Bullorsky; Australia: C. Arthur, A. Grigg, R. Herrmann, T. Hughes, K. Taylor; Austria: P. Valent; Belgium: M. Andre, A. Bosly, D. Bron, J. Van Droogenbroeck, G. Verhoef; Brazil: N. Hamerschlak, A. Moellmann, A. Souza; Canada: D. Forrest, C. Gambacorti-Passerini, A.R. Turner; Czech Republic: H. Klamova, J. Mayer; Denmark: I. Dufva, H. Hasselbalch, J. Nielsen; Finland: K. Porkka; France: J. Cahn, A. Charbonnier, C. Cordonnier, H. Dombret, T. Facon, F. Guilhot-Gaudeffroy, J. Harrousseau, M. Leporrier, F. Maloisel, G. Marit, M. Michalet, J. Reiffers, P. Rousselot; Germany: C. Bokemeyer, G. Ehninger, T. Fischer, A. Hochhaus, D. Niederwieser, E. Nikiforakis, O. Ottmann; Hungary: T. Masszi; Ireland: E. Conneally; Israel: A. Nagler; Italy: E. Abruzzese, S. Amadori, M. Baccarani, F. Ferrara, V. Liso, E. Pogliani, B. Rotoli, G. Saglio; The Netherlands: J. Cornelissen; Norway: H. Hjorth-Hansen; Peru: L. Chong, J. Navarro; Philippines: P. Caguioa; Poland: A. Dmoszynska, A. Hellmann, J. Holowiecki, W. Jedrzejczak, T. Robak, A. Skotnicki; Republic of Korea: H.-J. Kim, K.-H. Lee, S.-S. Yoon; Russian Federation: A. Zaritsky; Singapore: Y.-T. Goh; South Africa: J. Lombard, V. Louw, N. Novitzky, P. Ruff; Spain: F. Cervantes, J. Odriozola, M. Sanz, J. Steegmann; Sweden: M. Ekblom, B. Markevarn, B. Simonsson, L. Stenke; Switzerland: A. Gratwohl; Taiwan: P.-M. Chen, L. Shih, J. Tang; Thailand: S. Jooter; United Kingdom: J. Apperley, R. Clark, T. Holyoake, S. O'Brien; United States: J. Catlett, M. Devetten, B. Druker, P. Emanuel, H. Fernandez, S. Goldberg, F. A. Greco, M. Kalaycio, R. Larson, M. Lilly, J. Lister, K. McDonagh, R. L. Paquette, S. Petersdorf, A. Rapoport, C. Schiffer, J. Schwartz, N. P. Shah, T. Shea, R. T. Silver, R.M. Stone, R. Strair, M. Talpaz, S. Tarantolo.

Footnotes

Presented at the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 6-9, 2008. A previous abstract presented data from the same study with a shorter duration of follow-up.31

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: H.K. designed and performed research, wrote the manuscript, and analyzed and interpreted data; J.C. reviewed the manuscript, analyzed and interpreted data, and performed research; D.-W.K. and M.S.T. performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; P.D.-L. performed research and analyzed the manuscript; R.P. collected data, interpreted and analyzed the data, and provided suggestions for the manuscript; J.D.P. performed research and collected data; M.C.M. contributed analytical tools and collected data; J.P.R. designed and performed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; H.J.K. interpreted data, contributed patients, and had significant input to the manuscript; N.K. performed research; M.B.B.-G. analyzed and interpreted data; and C.Z. analyzed and interpreted data and performed statistical analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.K. has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. J.C. has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Wyeth. D.-W.K. has provided consultancy for Novartis, Wyeth, and Merck, and has received research funding from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Wyeth; he has received honoraria from Novartis and Wyeth. R.P. has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. J.D.P. has received honoraria from Genzyme. M.C.M. has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb. J.P.R. has provided consultancy for Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck, and has received research funding from Novartis and Bristol-Myers Squibb; he has received honoraria from Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck, and has membership with Nativis (unpaid). H.J.K. has provided consultancy for Bristol-Myers Squibb. N.K. is a clinical trials investigator and member of the Expert Panel of Hematological Research. M.B.B.-G. and C.Z. are employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. M.S.T. and P.D.-L. declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hagop Kantarjian, Department of Leukemia, Unit 428, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, PO Box 301402, Houston, TX 77030-1402; e-mail: hkantarj@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Advanced-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2003;40:79–86. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Giles F, et al. New insights into the pathophysiology of chronic myeloid leukemia and imatinib resistance. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:913–923. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, et al. Chronic myelogenous leukemia: biology and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:207–219. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mughal TI, Goldman JM. Chronic myeloid leukemia: why does it evolve from chronic phase to blast transformation? Front Biosci. 2006;11:198–208. doi: 10.2741/1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lionberger JM, Wilson MB, Smithgall TE. Transformation of myeloid leukemia cells to cytokine independence by Bcr-Abl is suppressed by kinase-defective Hck. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18581–18585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radich JP, Dai H, Mao M, et al. Gene expression changes associated with progression and response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talpaz M, Silver RT, Druker BJ, et al. Imatinib induces durable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2002;99:1928–1937. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, et al. Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: results of a phase II study. Blood. 2002;99:3530–3539. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottmann OG, Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, et al. A phase 2 study of imatinib in patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoid leukemias. Blood. 2002;100:1965–1971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochhaus A, La Rosee P. Imatinib therapy in chronic myelogenous leukemia: strategies to avoid and overcome resistance. Leukemia. 2004;18:1321–1331. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Talpaz M, et al. Outcome of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia post-imatinib mesylate failure. Cancer. 2007;109:1556–1560. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Hare T, Walters DK, Stroffregen EP, et al. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistance Abl kinase domain mutations. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500–4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam S, Kim D, Cheng JQ, et al. Action of the Src family kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (BMS-354825), on human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9185–9189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombardo LJ, Lee FY, Chen P, et al. Discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methyl-phenyl)-2-(6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazin-1-yl)-2-mehtylpyrimidin-4-ylamino)thiazole-5-carboxamide (BMS-354825), a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical assays. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6658–6661. doi: 10.1021/jm049486a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochhaus A, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, et al. Dasatinib induces notable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of imatinib therapy. Blood. 2007;109:2303–2309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Hamerschlak N, et al. Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of first-line imatinib: a randomized phase 2 trial. Blood. 2007;109:5143–5150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guilhot F, Apperley J, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib induces significant hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase. Blood. 2007;109:4143–4150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes J, Rousselot P, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib induces complete hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis. Blood. 2007;109:3207–3213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ottmann O, Dombret H, Martinello G, et al. Dasatinib induces rapid hematologic and cytogenetic responses in adults patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: interim results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2007;110:2309–2315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clopper C, Pearson E. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dombret H, Ottmann OG, Goh Y, et al. Dasatinib 140 mg QD vs 70 mg bid in advanced-phase CML or Ph(+) ALL resistant or intolerant to imatinib: results from a randomized, phase III trial (CA180035). Haematologica. 2007;92(suppl 2):319. Abstract 859. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah NP, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, et al. Intermittent target inhibition with dasatinib 100 mg once daily preserves efficacy and improved tolerability in imatinib-resistant and -intolerant chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3204–3212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apperley JF, Cortes JM, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase after imatinib failure: 14-month median follow-up of all patients enrolled in the START A trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jun 1; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3339. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christopher LJ, Cui D, Wu C, et al. Metabolism and disposition of dasatinib after oral administration to humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1357–1364. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah NP, Kasap C, Weier C, et al. Transient potent BCR-ABL inhibition is sufficient to commit chronic myeloid leukemia cells irreversibly to apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Hochhaus A, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib pharmacokinetics and exposure-response (E-R): relationship to safety and efficacy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:175S. Abstract 3590. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Coutre P, Giles FJ, Apperley J, et al. Nilotinib in accelerated phase chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML-AP) patients with imatinib-resistance or -intolerance: update of a phase II study [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:384S. Abstract 7050. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, et al. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305:399–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1099480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dombret H, Ottoman O, Goh Y, et al. Dasatinib 140 mg QD vs 70 mg BID in advanced phase CML or Ph+ ALL resistant or intolerant to imatinib: results from a randomized, phase-III trial (CA180035) [abstract 0859]. Haematologica (EHA Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2007;92(suppl 1):319. [Google Scholar]