Mortality Among Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Denmark (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2016 Oct 27.

Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Several mental disorders have consistently been found to be associated with decreased life expectancy, but little is known about whether this is also the case for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether persons who receive a diagnosis of OCD are at increased risk of death.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Using data from Danish registers, we conducted a nationwide prospective cohort study with 30 million person-years of follow-up. The data were collected from Danish longitudinal registers. A total of 3 million people born between 1955 and 2006 were followed up from January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2011. During this period, 27 236 people died. The data were analyzed primarily in June 2015.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

We estimated mortality rate ratios (MRRs), adjusted for calendar year, age, sex, maternal and paternal age, place of residence at birth, and somatic comorbidities, to compare persons with OCT with persons without OCD.

RESULTS

Of 10 155 persons with OCD (5935 women and 4220 men with a mean [SD] age of 29.1 [11.3] years who contributed a total of 54 937 person-years of observation), 110 (1.1%) died during the average follow-up of 9.7 years. The risk of death by natural or unnatural causes was significantly higher among persons with OCD (MRR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.31–2.12] for natural causes; MRR, 2.61 [95% CI, 1.91–3.47] for unnatural causes) than among the general population. After the exclusion of persons with comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, or substance use disorders, OCD was still associated with increased mortality risk (MRR, 1.88 [95% CI, 1.27–2.67]).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

The presence of OCD was associated with a significantly increased mortality risk. Comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, or substance use disorders further increased the risk. However, after adjusting for these and somatic comorbidities, we found that the mortality risk remained significantly increased among persons with OCD.

Several mental disorders have consistently been found to be associated with a shortened life expectancy, but little is known about whether this association can also be observed for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which is a major mental health condition accompanied by severe distress, high levels of disability, and disruption of a person’s social and occupational functioning.1,2 The World Health Organization has ranked OCD as one of the 10 most disabling medical conditions worldwide.2 The prevalence rates of psychiatric comorbidities in persons with OCD are strikingly high (up to 80%)3–5 and are considered one of the most important factors that can worsen the outcome for persons with OCD. Persons with the disorder still have long delays in accessing effective treatments; if untreated, OCD generally persists and becomes chronic.6,7

Thus, many reasons exist to believe that OCD is associated with an increased health burden and an increased risk of mortality. However, to the best of our knowledge, only 1 study8 has compared the mortality of persons who received a diagnosis of OCD with the mortality of controls from the general population. This population-based study8 was of limited sample size (N = 389), and its results highly depended on the statistical models used to analyze the data. Whether OCD is associated with increased mortality, therefore, remained unclear.

To compare rare events, such as premature death, among persons with OCD and healthy controls, large sample sizes are needed. The longitudinal Danish registers offer such a unique opportunity. We conducted a population-based study to investigate the prevalence and risks of premature mortality among 10 155 persons who received a diagnosis of OCD. We compared persons who received a diagnosis of OCD with persons from the general population and unaffected siblings (ie, controls). In addition, we examined the added effects of psychiatric and physical comorbidities on mortality rates among persons with OCD. This study design will enable us to adjust for potential confounding factors in an unprecedented manner, thus advancing our understanding of the underlying causes of premature mortality among persons with OCD.

Method

Study Setting

Using data from Danish registers, we conducted a nationwide prospective cohort study. The main exposure variable was defined as the first psychiatric inpatient or outpatient contact for OCD. The outcome variable was defined as death by any natural cause (disease or medical condition) or unnatural cause (suicide, accident, or homicide) within the follow-up period. The cohort consisted of people born in Denmark between January 1, 1955, and November 31, 2006. The follow-up period started on the participants first birthday or January 1, 2002, whichever came later. The follow-up period ended on the date of emigration from Denmark, the date of death, or December 31, 2011, whichever came first. This information provided us with a maximum follow-up period of 10 years and a maximum age of 57 years for the cohort members. We focused on this 10-year period because during this period, the causes of death were grouped based on the same coding procedure. We particularly focused on young age groups, to avoid dilution of the findings by large mortality effects among older people. Data on cohort members were collected by linking 4 Danish population registers (see the eAppendix in the Supplement). All residents of Denmark, including immigrants, get a unique personal identification number that is used in all national registers, which enables us to link data across these registers. Our study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The investigators were blind to the identity of study members, and because the study did not result in any contact with the participants, no written informed consent was required according to Danish law.

Exposure Variables

The main exposure variable was defined as first contact due to OCD. Using the Danish Psychiatric Central Register9 and the Danish National Patient Register,10 we identified all patients who received a diagnosis of OCD based on the ICD-8 (code 300.39) and the ICD-10 (code F42). These registers comprehensively represent psychiatric hospital admissions to inpatient and outpatient facilities because private psychiatric hospitals do not exist in Denmark. The date of onset was defined as the day of the first contact for the diagnosis in question.

Outcome Variables

The outcome of interest was time to death. The date and cause of death were identified from the Danish Register of Causes of Death.11 All-cause mortality was defined using ICD-10 codes A00 through Y98 and was categorized into the following groups: deaths from diseases and physical conditions (natural death; ICD-10 codes A00-R99) and deaths from external causes (unnatural death; ICD-10 codes V01-Y98). Unnatural causes of death comprised suicides (ICD-10 codes X60-X84 and Y87.0), homicides (ICD-10 codes X85-Y09 and Y87.1), and accidents (ICD-10 codes V01-X59, Y10-Y86, Y87.2, and Y88-Y89). Natural causes included death by cancer (ICD-10 codes C00-D48), cardiac diseases (ICD-10 codes I00-I99), respiratory diseases (ICD-10 codes J00-J99), digestive conditions (ICD-10 codes K00-K93), and remaining causes (ie, deaths by other somatic illnesses such as infections and nervous disorders, but also unknown causes).

Covariates

Data on age, sex, calendar period, maternal and paternal age at time of birth, and place of residence at time of birth were derived from the Danish Civil Registration System.11 Somatic comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which refers to a sum score built on 19 severe chronic diseases weighted from 1 to 6 corresponding to the severity of the disease.12 We further assessed the most common psychiatric comorbidities in persons with OCD and derived information on anxiety disorders (ICD-10 codes F40.00-F40.20, F41.00-F41.10, and F43.00-F43.10), depression (ICD-8 codes 296.x9, 298.09, 298.19, 300.49, and 301.19 and ICD-10 codes F32.00-F33.99, F34.10-F34.90, and F38.00-F39.99), and substance use disorders (ICD-8 codes 291.xx, 303.xx, 304.xx, 571.09, and 571.1x and ICD-10 codes F10-F16, F18, F19, I85, and K70) from the Danish Psychiatric Central Register9 and the Danish National Patient Register.10

Sibling Control Studies

We performed additional analyses that used unaffected full siblings of patients as controls to account for possible familial confounding. In these analyses, we identified as cases those persons with OCD who also had full siblings without OCD, and we compared those persons with their unaffected full siblings using logistic regression for matched design. Comparisons of siblings raised in the same family will automatically match on many unmeasured shared factors, including cultural background, parental characteristics, child-rearing practices, and— particularly for monozygotic twins—genetics.13

Data Analyses

Mortality rate ratios (MRRs) were calculated for all causes, as well as for natural and unnatural causes of death separately. We fitted 2 statistical models to these outcomes, using the log-linear Poisson regression with the GENMOD procedure in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc). In the first model, we adjusted for demographic characteristics; in the second model, we adjusted additionally for somatic comorbidity. We also aimed to disentangle the effects of pure OCD and comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use disorders on mortality risk. In our sensitivity analyses, we assessed differences in the association of mortality with OCD by sex, age at death, and time since diagnosis. A more detailed description can be found in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Results

From January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2011, a total of 3 270 650 persons were included in the study cohort contributing 31 213 252 person-years at risk. For 51 373 cohort members (1.6%), follow-up was ended before the end of the study; 50 521 emigrated from Denmark, and 852 were lost to follow-up. The mean follow-up time for the cohort members was 9.7 years. A total of 27 236 persons in our cohort died during the follow-up period, corresponding to a mortality rate of 8.7 deaths per 10 000 person-years.

Within this cohort, we identified 10 155 persons with OCD, 40 439 with anxiety disorders, 76 202 with depression, and 134 787 with substance use disorders. Persons who received a diagnosis of OCD (5935 females and 4220 males with a mean [SD] age of 29.1 [11.3] years) contributed a total of 54 937 person-years of observation. Of the 10 155 persons with OCD, 1810 (17.8%) received a comorbid diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, 2682 (26.4%) received a comorbid diagnosis of depression, and 1362 (13.4%) received a comorbid diagnosis of a substance use disorder. A total of 110 persons with OCD (1.1%) died during the follow-up period, including 82 persons (1.5%) with comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, or substance use disorders. Table 1 shows the details of the mortality rates for a priori selected covariates.

Table 1.

General Description of the Study Cohort

| Covariate | No. of Deaths | Person-Years | Rate per 1000 Person-Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calendar year | |||

| 2002–2005 | 8928 | 12 022 230 | 7.4262 |

| 2006–2010 | 14 915 | 15 994 350 | 9.3252 |

| 2011 | 3393 | 3 196 672 | 10.6142 |

| Age, y | |||

| <20 | 1877 | 11 466 668 | 1.6369 |

| 20–29 | 2564 | 5 517 319 | 4.6472 |

| 30–39 | 5342 | 6 735 067 | 7.9316 |

| 40–50 | 12 546 | 6 289 005 | 19.9491 |

| >50 | 4907 | 1 205 193 | 40.7155 |

| Maternal age, y | |||

| <25 | 12 088 | 10 335 691 | 11.6954 |

| 25–29 | 7915 | 11 089 582 | 7.1373 |

| 30–34 | 4600 | 6 858 201 | 6.7073 |

| 35–40 | 646 | 215 264 | 300.096 |

| >40 | 1987 | 2 714 514 | 73.199 |

| Paternal age, y | |||

| <35 | 21 054 | 24 428 081 | 8.6188 |

| 35–39 | 1117 | 394 972 | 28.2805 |

| 40–44 | 4773 | 6 306 711 | 7.5681 |

| 45–49 | 192 | 57 139 | 33.6023 |

| 50–55 | 69 | 180 255 | 37.7971 |

| >55 | 31 | 8094 | 38.3014 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 9138 | 15 169 221 | 6.0240 |

| Male | 18 098 | 16 044 031 | 11.2802 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Capital | 5284 | 4 731 846 | 11.1669 |

| Capital suburb | 2344 | 3 444 079 | 6.8059 |

| Provincial city | 3368 | 3 931 412 | 8.5669 |

| Provincial town | 8990 | 10 087 298 | 8.9122 |

| Rural area | 7250 | 9 018 616 | 8.0389 |

| Somatic comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 10 414 | 27 083 415 | 3.845 |

| 1 | 3663 | 2 831 430 | 12.937 |

| 2 | 3638 | 801 920 | 45.366 |

| 3 | 1908 | 246 314 | 77.462 |

| ≥4 | 7613 | 250 173 | 304.310 |

| Anxiety disorders | |||

| Yes | 979 | 246 508 | 39.7147 |

| No | 26 257 | 30 966 744 | 8.4791 |

| Depression | |||

| Yes | 2290 | 437 423 | 52.3521 |

| No | 24 946 | 30 775 829 | 8.1057 |

| Substance abuse | |||

| Yes | 8747 | 947 062 | 92.3593 |

| No | 18 489 | 30 266 189 | 6.1088 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | |||

| Yes | 110 | 54 936 | 20.0234 |

| No | 27 126 | 31 158 316 | 8.7059 |

All-Cause Mortality Rates Among Persons With OCD

Adjusted for sociodemographic variables, the all-cause MRR for persons with OCD was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.76–2.57) compared with persons from the general population without this diagnosis (Table 2). Additional adjustment for somatic comorbidity reduced the MRR to 2.00 (95% CI, 1.65–2.40). Although diagnoses of OCD were consistently associated with higher mortality rates, time since first diagnosis did not have a significant effect (eTable in the Supplement). The interaction between sex and OCD, although clinically relevant, was not statistically significant (P = .63). The fully adjusted MRR for women with OCD (1.63 [95% CI, 1.26–2.06]) was only marginally lower than the MRR for men (1.75 [95% CI, 1.30–2.31]) (Table 2). Restricting the cohort to persons younger or older than 45 years of age resulted in MRRs similar to those obtained from the overall cohort.

Table 2.

Mortality Rate Ratios of Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (2002–2011)

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | Mortality Rate Ratio (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Causes | Unnatural Causes | Natural Causes | |

| General population | 2.00 (1.65–2.40) | 2.61 (1.91–3.47) | 1.68 (1.31–2.12) |

| Men | 1.75 (1.30–2.31) | 2.23 (1.49–3.20) | 1.69 (1.19–2.30) |

| Women | 1.63 (1.26–2.06) | 3.15 (1.87–4.94) | 1.37 (0.94–1.93) |

Causes of Death Among Persons With OCD

Of the 110 persons with OCD who died during the follow-up period, 66 (60.0%) died of natural causes, and 44 (40.0%) of unnatural causes. Among persons with OCD, the MRRs were 1.88 (95% CI, 1.46–2.37) for natural causes and 2.64 (95% CI, 1.93–3.52) for unnatural causes of death compared with persons without OCD and were adjusted for sociodemographic variables (Table 2). Taking somatic comorbidities into account reduced the MRRs among persons with OCD to 1.68 (95% CI, 1.31–2.12) for natural causes and 2.61 (95% CI, 1.91–3.47) for unnatural causes of death compared with persons without OCD (Table 2). The MRRs for natural causes were only significantly elevated among men (1.69 [95% CI, 1.19–2.30]) compared with women (1.37 [95% CI, 0.94–1.93]). In contrast, the MRRs for unnatural causes of death were slightly higher among women (3.15 [95% CI, 1.87–4.94]) than men (2.23 [95% CI, 1.49–3.20]) (Table 2). The cause-specific MRRs were highest for suicides (3.02 [95% CI, 1.85–4.63]) and accidents (2.09 [95% CI, 1.31–3.13]) among persons with OCD.

To account for familial effects, we compared patients with OCD and their unaffected siblings (n = 14 834) with regard to all-cause mortality (MRR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.07–3.27]), natural causes (MRR, 1.91 [95% CI, 1.08–3.36]), and unnatural causes of death (MRR, 3.81 [95% CI, 1.13–12.78]). We found no evidence of familial confounding for causes of death (because the risk estimates were significant and of the same magnitude as those for the controls from the general population) (Table 3).

Table 3.

MRRs of Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Compared With Population and Sibling Controls (2002–2011)

| Cause of Mortality | Population Controls | Sibling Controls, OR (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRR(95% CI)a | MRR(95% CI)b | ||

| All | 2.14 (1.76–2.57) | 2.00 (1.65–2.40) | 1.87 (1.07–3.27) |

| Unnatural | 2.64 (1.93–3.52) | 2.61 (1.91–3.47) | 3.81 (1.13–12.78) |

| Natural | 1.88 (1.46–2.37) | 1.68 (1.31–2.12) | 1.91 (1.08–3.36) |

Influence of Comorbid Anxiety Disorders, Depression, and Substance Use Disorders

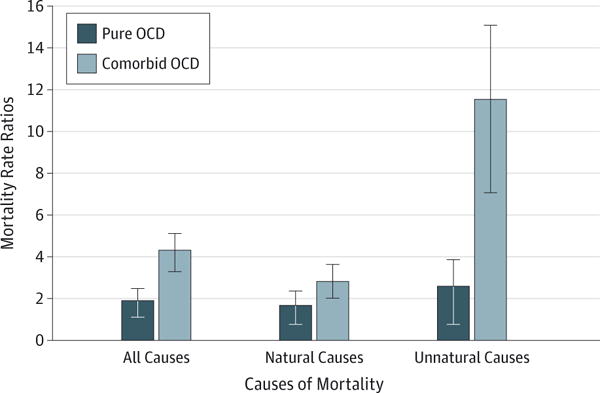

Comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, and substance use disorders had a significant effect on the mortality among persons with OCD (Table 4). The MRRs of persons with OCD and a comorbid diagnosis of anxiety disorders or depression (2.47 [95% CI, 1.57–3.65]) and of persons with OCD and a comorbid diagnosis of substance use disorder (6.32 [95% CI, 4.26–8.97]) were higher than those of persons with only OCD (1.88 [95% CI, 1.27–2.67]). Persons with OCD and several comorbidities (ie, OCD with substance use disorder and either anxiety disorder or depression) further had an increased risk for premature mortality (MRR, 5.47 [95% CI, 3.78–7.60]). Persons with OCD and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression (MRR, 2.04 [95% CI, 1.18–3.26] for natural causes of death; MRR, 4.12 [95% CI, 1.77–7.99] for unnatural causes of death), persons with OCD and a comorbid diagnosis of substance use disorder (MRR, 4.73 [95% CI, 2.91–7.20] for natural causes of death; MRR, 15.29 [95% CI, 7.34–27.61] for unnatural causes of death), and persons with OCD and both comorbidities (MRR, 2.51 [95% CI, 1.45–4.01] for natural causes of death; MRR, 29.38 [95% CI, 17.51–45.74] for unnatural causes of death) also had higher MRRs for natural and unnatural causes of death than those persons with only OCD (MRR, 1.66 [95% CI, 0.99–2.58] for natural causes of death; MRR, 2.61 [95% CI, 1.35–4.47] for unnatural causes of death). The additional exclusion of common comorbidities such as schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or conduct disorder still resulted in an increased MRR among persons with only OCD (1.71 [95% CI, 1.10–2.51]) (Figure).

Table 4.

Mortality Rate Ratio of Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Stratified by Comorbidities (2002–2011)

| Diagnosis | Mortality Rate Ratio (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Causes | Unnatural Causes | Natural Causes | |

| OCD | 1.88(1.27–2.67) | 2.61(1.35–4.47) | 1.66(0.99–2.58) |

| Substance use disorders | 4.92(4.77–5.07) | 11.57(10.92–12.26) | 3.66(3.53–3.79) |

| Anxiety disorders or depression | 2.36(2.22–2.51) | 6.95(6.28–7.67) | 1.49(1.37–1.62) |

| Substance use disorders and anxiety disorders or depression | 5.89(5.59–6.30) | 25.51(23.39–27.77) | 3.49(3.27–3.72) |

| Anxiety disorders or depression and OCD | 2.47(1.57–3.65) | 4.12(1.77–7.99) | 2.04(1.18–3.26) |

| Substance use disorders and OCD | 6.32(4.26–8.97) | 15.29(7.34–27.61) | 4.73(2.91–7.20) |

| Substance use disorders, OCD, and anxiety disorders or depression | 5.47(3.78–7.60) | 29.38(17.51–45.74) | 2.51(1.45–4.01) |

Figure. Mortality Rate Ratios of Persons With Pure or Comorbid OCD (2002–2011).

Mortality rate ratios were adjusted for calendar year, age, sex, maternal and paternal age, place of residence at time of birth, somatic comorbidity, and the interaction of age and sex. “Pure” obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) indicates OCD without comorbidities. Comorbidities include anxiety disorders, depression, and substance abuse disorders.

Discussion

In this nationwide prospective cohort study, the risk of premature death among persons with OCD was doubled compared with the general population. Around 40% of all deaths among persons with OCD were attributed to unnatural causes, with increased mortality rates observed for both suicides and accidents among persons with OCD. The estimates seemed not to be confounded by factors shared by the siblings because the risk estimates remained significantly elevated in between-siblings analyses. These findings present new information on long-term outcomes of OCD, which should be taken into account in the clinical management of OCD in psychiatry and primary care services.

Our results also showed that comorbid anxiety disorders or depression, as well as substance use disorders, had a strong influence on the risk of premature death among persons with OCD. In particular, comorbid substance use disorders were observed to increase mortality risk to a large extent. However, the excess mortality observed to be associated with OCD was only partly explained by these comorbid conditions. The mortality rate was still increased by almost 90% among persons with OCD only compared with those persons without OCD (MRR, 1.88), when we excluded persons who received a comorbid diagnosis of anxiety disorder, depression, or substance use disorder.

Among persons with OCD, the highest MRRs were observed for deaths due to unnatural causes (ie, accidents, homicides, and suicides). This pattern of high mortality due to unnatural causes is comparable to that among persons with other severe mental disorders.14–17 A recent meta-analysis18 revealed a significant association of OCD and suicidality with an effect size of 0.66. However, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis18 focused on suicidal ideation/behavior and not on actually completed suicides. In our study, the risk of committing suicide was tripled among persons with OCD. The risk of suicide among psychiatric patients has been studied before,19–22 whereas less attention has been given to the risk and prevention of accidental deaths, even though the latter is more common. Interestingly, we observed that the risk of death by accidents was doubled among persons with OCD. Ours is the first study pinpointing an increased risk for serious accidents among persons with OCD because we are unaware of any prior studies examining the risk of accidents among persons with OCD. The reason for a higher risk of accidents could be due to the notion that patients with OCD may have problems controlling their impulsivity,23 or that engaging in obsessions and compulsions may evoke problems of attention, documented in neuropsychological examinations.24 Interestingly, the risk for unnatural deaths among persons with OCD remained significantly elevated after the exclusion of cases with comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, or substance use disorders.

With regard to absolute numbers, most persons with OCD (ie, 66 of 110 [60.0%]) died of natural causes of death. Thus, the escalation of deaths from diseases and medical conditions among persons with OCD is an important component of the observed excess mortality risk. Interestingly, the effects of comorbid anxiety disorders, depression, or substance use disorders on mortality risk due to natural causes among persons with OCD were less pronounced, despite the fact that most persons with these comorbidities died of natural causes. Severe psychiatric disorders have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of somatic comorbidity,25,26 and psychiatric patients might be underdiagnosed and undertreated for medical conditions.27 Physical complications and health problems have been described in relation to severe enduring OCD, as well as milder forms of the disorder.28–30 Other hazardous unhealthy lifestyles such as physical inactivity,31 increased smoking,32 unhealthy eating patterns,29,33 as well as stress and biological dysregulation,34–36 might have further contributed to the observed excess mortality among persons with OCD. In some cases, the compulsive thoughts and rituals themselves might become harmful.29 We also cannot entirely exclude the possibility that the medication used to treat OCD, such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, have contributed to higher mortality rates.

Importantly, the all-cause mortality risk among persons with OCD in our study lies within the range reported for mental disorders in a recent meta-analysis.37 Mortality rates among persons with OCD seemed to be lower than among persons with psychoses37–39 or substance use disorders,40,41 but the MRRs were of the same magnitude as those observed among persons with mood and anxiety disorders37,42,43 or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,44 which indicates that a general psychopathological factor may be underlying the increased mortality risk of mental disorders. The present findings, therefore, make an important contribution to the literature by showing that the mortality risk of OCD is highly comparable to that of more commonly examined mental disorders, which marks the need for more prevention and medical care for persons with OCD.

We studied a nationwide population-based cohort that included all persons born in Denmark between 1955 and 2006, with almost complete follow-up data for up to 57 years. Thus, our findings are unlikely to be explained by biases in the selection of the study population or nondifferentiated attrition during follow-up. However, there are 2 main limitations in this study. First, we used patient registers to identify persons with OCD because it was necessary to use routinely collected data to provide precision for the fairly rare outcomes investigated. Despite a generally acceptable accuracy of diagnoses for mental disorders in the registers,45–51 the included persons treated at hospitals probably have more severe symptoms and greater impairment than do those treated by psychiatrists and pediatricians in private practices. Thus, although our data on OCD diagnoses are of good quality50 and were obtained independently of the outcome, our findings might not be representative of the entire spectrum of OCD but of only those persons with more severe OCD. Second, some of the causes of death may be prone to misclassification. It is possible that some accidental deaths, in fact, were suicides, whereas most deaths classified as suicides reflect true suicides. This potential misclassification might lead to an underestimation of the cases of suicide in our cohort and thereby might have resulted in an underestimation of the observed MRRs for suicide.

Conclusions

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a common mental disorder known to cause severe impairment across a person’s life span. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting an increased mortality risk among persons with OCD. We have found an increased risk of death by both natural and unnatural causes among persons with OCD. The co-occurrence of anxiety disorders or depression and substance use disorders resulted in a further increased risk of death. We found no familial confounding in mortality among persons with OCD, strengthening the hypothesis that OCD lies on the causal pathway to premature death. These findings represent an important first step toward identifying the underlying mechanisms for the risk of premature death among persons with OCD and stress the importance of using a thorough diagnostic process to identify comorbidities and accompanying problems. Moreover, our results emphasize that a focused effort on improving long-term outcomes among persons with OCD, including targeted treatment and suicide prevention, is essential.

Supplementary Material

Supplement

At a Glance.

- We conducted a large-scale prospective cohort study to examine the mortality risk among persons who received a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Persons with OCD had double the risk of premature death compared with the general population.

- Around 40% of all deaths among persons with OCD were attributed to unnatural causes, with increased mortality rates observed for both suicides and accidents among persons with OCD.

- Sibling-control analyses revealed no familial confounding for causes of death because risk estimates remained significantly elevated among siblings.

- These findings present new information on long-term outcomes of OCD, which might help to improve the clinical management of OCD in psychiatry and primary care services.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, within the context of the Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research and Mental Health in Primary Care. Dr Meier received further funding from the Mental Health Services, Capital Region, Copenhagen, Denmark, and Dr Mortensen received funding from the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Meier had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Meier, Plessen.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Meier.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mattheisen, Mors, Schendel, Mortensen, Plessen.

Statistical analysis: Meier.

Obtained funding: Mattheisen, Mortensen, Plessen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Schendel.

Study supervision: Mattheisen, Mors, Plessen.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Crino R, Slade T, Andrews G. The changing prevalence and severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder criteria from DSM-III to DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):876–882. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veale D, Roberts A. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMJ. 2014;348:g2183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive severity spectrum in the community: prevalence, comorbidity, and course. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254(3):156–164. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy HC, McLean CP, Yadin E, Foa EB. Characteristics of individuals seeking treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lochner C, Fineberg NA, Zohar J, et al. Comorbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): a report from the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollander E, Stein DJ, Kwon JH, et al. Psychosocial functions and economic costs of obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectrums. 1997;2(10):16–25. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900011068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skoog G, Skoog I. A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(2):121–127. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton WW, Roth KB, Bruce M, et al. The relationship of mental and behavioral disorders to all-cause mortality in a 27-year follow-up of 4 epidemiologic catchment area samples. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(9):1366–1377. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jørgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen JH. The Danish National Hospital Register: a valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull. 1999;46(3):263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 suppl):26–29. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Onofrio BM, Lahey BB, Turkheimer E, Lichtenstein P. Critical need for family-based, quasi-experimental designs in integrating genetic and social science research. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 1):S46–S55. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Mental disorders and vulnerability to homicidal death: Swedish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Mental disorders and risk of accidental death. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(3):297–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.123992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):64–70. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angelakis I, Gooding P, Tarrier N, Panagioti M. Suicidality in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balci V, Sevincok L. Suicidal ideation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1–2):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres AR, Ramos-Cerqueira AT, Ferrão YA, Fontenelle LF, do Rosário MC, Miguel EC. Suicidality in obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and relation to symptom dimensions and comorbid conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(1):17–26. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05651blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso P, Segalàs C, Real E, et al. Suicide in patients treated for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(3):300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollander E, Greenwald S, Neville D, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Weissman MM. Uncomplicated and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder in an epidemiologic sample. Depress Anxiety. 4(3):1996–1997. 111–119. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:3<111::AID-DA3>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ettelt S, Ruhrmann S, Barnow S, et al. Impulsiveness in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from a family study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(1):41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abramovitch A, Abramowitz JS, Mittelman A. The neuropsychology of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campayo A, de Jonge P, Roy JF, et al. ZARADEMP Project Depressive disorder and incident diabetes mellitus: the effect of characteristics of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):580–588. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Bingham SA, Khaw KT. Depression and ischemic heart disease mortality: evidence from the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):515–523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07061018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Agerbo E, Gasse C, Mortensen PB. Somatic hospital contacts, invasive cardiac procedures, and mortality from heart disease in patients with severe mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):713–720. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albert U, Aguglia A, Chiarle A, Bogetto F, Maina G. Metabolic syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a naturalistic Italian study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonsson U, Bohman H, von Knorring L, Olsson G, Paaren A, von Knorring AL. Mental health outcome of long-term and episodic adolescent depression: 15-year follow-up of a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(3):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witthauer C, Gloster AT, Meyer AH, Lieb R. Physical diseases among persons with obsessive compulsive symptoms and disorder: a general population study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(12):2013–2022. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0895-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Cho MJ, Cho SJ, et al. Relationship between physical activity and mental health in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaisoorya TS, Janardhan Reddy YC, Thennarasu K, Beena KV, Beena M, Jose DC. An epidemological study of obsessive compulsive disorder in adolescents from India. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;61:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramaniam M, Picco L, He V, et al. Body mass index and risk of mental disorders in the general population: results from the Singapore Mental Health Study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faravelli C, Lo Sauro C, Godini L, et al. Childhood stressful events, HPA axis and anxiety disorders. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(1):13–25. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kluge M, Schüssler P, Künzel HE, Dresler M, Yassouridis A, Steiger A. Increased nocturnal secretion of ACTH and cortisol in obsessive compulsive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(11):928–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray SM, Bloch MH. Systematic review of proinflammatory cytokines in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(3):220–228. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):324–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westman J, Wahlbeck K, Laursen TM, et al. Mortality and life expectancy of people with alcohol use disorder in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(4):297–306. doi: 10.1111/acps.12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaridze D, Brennan P, Boreham J, et al. Alcohol and cause-specific mortality in Russia: a retrospective case-control study of 48,557 adult deaths. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2201–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuijpers P, Vogelzangs N, Twisk J, Kleiboer A, Li J, Penninx BW. Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):453–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markkula N, Härkänen T, Perälä J, et al. Mortality in people with depressive, anxiety and alcohol use disorders in Finland. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):143–149. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.094904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, Pedersen MG. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573–581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrne N, Regan C, Howard L. Administrative registers in psychiatric research: a systematic review of validity studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(6):409–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60(2):A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lauritsen MB, Jørgensen M, Madsen KM, et al. Validity of childhood autism in the Danish Psychiatric Central Register: findings from a cohort sample born 1990–1999. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(2):139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bock C, Bukh JD, Vinberg M, Gether U, Kessing LV. Validity of the diagnosis of a single depressive episode in a case register. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meier SM, Petersen L, Mattheisen M, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Laursen TM. Secondary depression in severe anxiety disorders: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(6):515–523. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00092-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessing L. Validity of diagnoses and other clinical register data in patients with affective disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(8):392–398. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(99)80685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement