INTEGRATE-neo: a pipeline for personalized gene fusion neoantigen discovery (original) (raw)

Abstract

Motivation

While high-throughput sequencing (HTS) has been used successfully to discover tumor-specific mutant peptides (neoantigens) from somatic missense mutations, the field currently lacks a method for identifying which gene fusions may generate neoantigens.

Results

We demonstrate the application of our gene fusion neoantigen discovery pipeline, called INTEGRATE-Neo, by identifying gene fusions in prostate cancers that may produce neoantigens.

Availability and Implementation

INTEGRATE-Neo is implemented in C ++ and Python. Full source code and installation instructions are freely available from https://github.com/ChrisMaherLab/INTEGRATE-Neo.

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

The mutational landscape of cancer genomes results in the production of tumor specific peptides recognizable by immune molecules. These so-called neoantigens can be exploited for personalized cancer immunotherapy (Heemskerk et al., 2013). To date, multiple studies have successfully used Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) to discover tumor specific neoantigens (Carreno et al., 2015; Gubin et al., 2014; Matsushita et al., 2012). These analyses have relied on somatic missense mutation-based neoantigen discovery workflows like pVAC-Seq (Hundal et al., 2016). Despite these successes, such methods do not consider gene fusions, which occur when two genes are rearranged in the genome to encode an aberrant transcript that may translate into a novel immunogenic peptide. To address this critical gap, we developed the first open source pipeline, called INTEGRATE-Neo, for gene fusion neoantigen discovery using NGS data. INTEGRATE-Neo expands the functionality of our highly accurate gene fusion discovery tool, INTEGRATE (Zhang et al., 2016). Here, we apply INTEGRATE-Neo to the TCGA prostate cohort data (PRAD) to demonstrate its utility for identifying gene fusion neoantigens that may serve as personalized cancer immunotherapy targets.

2 The INTEGRATE-neo pipeline

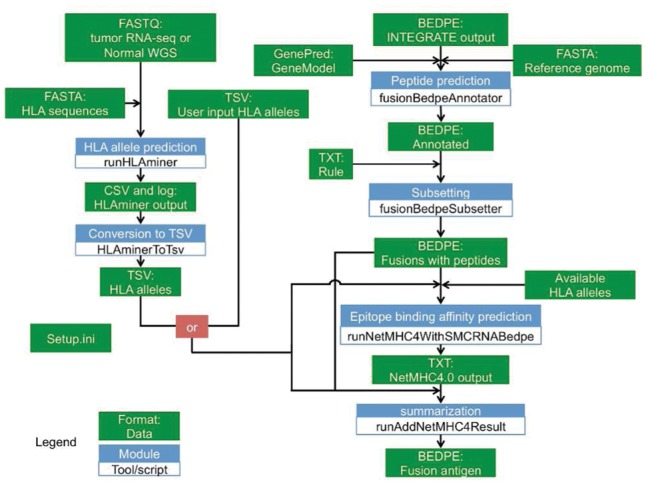

The gene fusion neoantigen discovery pipeline, INTEGRATE-Neo, is comprised of the following steps: (1) gene fusion peptide prediction, (2) HLA allele prediction and (3) gene fusion neoantigen discovery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of INTEGRATE-Neo. Green box is data, and blue box is a module

The first step takes (1) the human reference genome in FASTA format, (2) gene models in GenePred format and (3) gene fusions in BEDPE format predicted by INTEGRATE as input to predict gene fusion peptides. The BEDPE follows the standards provided by The ICGC-TCGA DREAM Somatic Mutation Calling-RNA Challenge (SMC-RNA). This step annotates the gene fusion predictions with information such as gene fusion exonic boundaries, open reading frames (ORF), and the predicted peptide at the fusion junction. Each codon within the 5′ gene partner is inferred according to the starting position of the 5′ ORF. The amino acids spanning the fusion junction are determined by the codons that result from merging the sequences of both the 5′ and 3′ gene partners. The 3′ reading frames, which may have shifted, are then calculated for the remaining portion of the gene fusion transcript downstream of the fusion junction until a stop codon is encountered. These annotations are appended as user defined columns to the BEDPE file. Gene fusions that do not produce a predicted fusion peptide are subsequently filtered.

The second step takes (1) high-throughput sequencing reads in FASTQ format and (2) reference HLA alleles in FASTA format as input to predict HLA alleles. It performs alignment using BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) and predicts the HLA alleles using HLAminer v 1.3 (Warren et al., 2012). This module outputs a Tab-separated value (TSV) file for the predicted HLA alleles that includes the four-digit HLA allele names, scoring metrics from HLAminer (score, e-value and confidence), and the prediction source. To increase the flexibility of INTEGRATE-Neo, a user has the option to upload their own HLA alleles in case they use another method, such as sequence-specific oligonucleotide probe hybridization and serotyping techniques, or already have algorithmic predicted results for their dataset.

The third neoantigen discovery step takes in (1) a TSV file for the predicted HLA alleles, (2) an annotated BEDPE file for the predicted gene fusion peptides and (3) a file of the list of HLA alleles supported by NetMHC v 4.0 (Andreatta and Nielsen, 2016). The epitope lengths supplied are 8–11 by default but can be defined by the user. For each epitope length, a FASTA file is prepared with peptides of 2_n_ − 1 amino acids, where n is the epitope length set by ‘−l’. The single amino acid in the middle spans the fusion junction. If the 5′ junction is at a full codon, then a peptide of 2_n_ − 2 amino acids is used. If a non-coding region (UTR) is encountered, the peptide sequence can be shorter than 2_n_ − 1 (or 2_n_ − 2). The summarization module keeps the epitope with the highest predicted binding affinity (nM) passed a user-defined threshold (default: 500) for each neoantigen. The final result is a BEDPE file with gene fusion neoantigen predictions. The summarization module appends the epitope sequences, binding affinities, HLA alleles and metrics of the HLA alleles, as user defined columns, to the output BEDPE file.

To ensure user-friendliness, all of the modules within INTEGRATE-Neo are designed as standalone tools with their own optional parameters. This enables users to incorporate INTEGRATE-Neo functions within their existing pipelines. INTEGRATE-Neo also ensures that all the modules are running the same version of the software. The paths to software and databases can be set in setup.ini.

3 Application to TCGA PRAD cohort

RNA-seq reads of 333 TCGA PRAD tumor samples were used to discover gene fusions and gene fusion neoantigens using INTEGRATE and INTEGRATE-Neo (Supplementary Methods). We discovered 1761 gene fusions in the 333 prostate cancer samples that generate 2707 fusion transcript isoforms (Supplementary Table S1). 2369 (87.5%) of the 2707 fusion transcripts have canonical exon boundaries, and 338 (12.5%) have junctions in other (non-exonic or truncated exonic) regions. 61 (3.5%) of the 1761 gene fusions are recurrent (occur in ≥ 2 patients; Supplementary Table S2; Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2) and 1700 (96.5%) are singletons (occur in 1 patient). INTEGRATE-Neo predicted 1600 (1300 singleton and 300 recurrent) fusion junction peptides for the 2,707 gene fusion transcripts. Of these, 240 (15%) (Supplementary Fig. S3a and Table S3) have epitopes with binding affinity scores ≤ 500 nM. The epitopes encompassed all epitope lengths as follows: 2.7%, 60.8%, 33.7% and 2.7% for 8, 9, 10 and 11 amino acids, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Interestingly, binding affinity scores skewed towards 1 rather than 500, with smaller scores indicating better binding affinities (Supplementary Fig. S3c). This pattern was consistent across all epitope lengths (Supplementary Fig. S3d). The most frequent gene fusion neoantigen from _TMPRSS2_-ERG is shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Epitope affinities in different HLA alleles and in recurrent gene fusions are shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

Analysis of the TCGA PRAD data with the aforementioned parameters on our servers with 2.50 GHz Intel Xeon processors had an average runtime of 75.1 ± 29.2 seconds and average memory usage of 1.88 ± 0.90 GB per patient using single thread highlighting the efficiency of INTEGRATE-Neo (Supplementary Fig. S6).

4 Discussion

Here, we described the first automated gene fusion neoantigen discovery pipeline, INTEGRATE-Neo, and demonstrated that it can efficiently process the TCGA prostate cancer patient cohort. This revealed predicted gene fusions neoantigens across a distribution of epitope binding affinities. Overall, INTEGRATE-Neo provides a valuable resource to the cancer community by complementing existing somatic missense mutation-based neoantigen discovery methods to ensure that no potential neoantigen is missed in the search for personalized immunotherapy targets.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Funding

This work was supported by an NIH National Cancer Institute R21CA185983-01 (to C.A.M.), NIH National Cancer Institute R00CA149182 (to C.A.M.) and a Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Andreatta M., Nielsen M. (2016) Gapped sequence alignment using artificial neural networks: application to the MHC class I system. Bioinformatics, 32, 511–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno B.M. et al. (2015) Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science, 348, 803–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubin M.M. et al. (2014) Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature, 515, 577–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk B. et al. (2013) The cancer antigenome. EMBO J., 32, 194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundal J. et al. (2016) pVAC-Seq: A genome-guided in silico approach to identifying tumor neoantigens. Genome Med., 8, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25, 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita H. et al. (2012) Cancer exome analysis reveals a T-cell-dependent mechanism of cancer immunoediting. Nature, 482, 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren R.L. et al. (2012) Derivation of HLA types from shotgun sequence datasets. Genome Med., 4, 95.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. (2016) INTEGRATE: gene fusion discovery using whole genome and transcriptome data. Genome Res., 26, 108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data