Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Promotes Endometrial Stromal Cells Migration and Invasion by Upregulating Autophagy in Endometriosis (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 Jun 1.

Published in final edited form as: Reproduction. 2017 Mar 27;153(6):809–820. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0643

Abstract

Endometriosis is a benign gynaecological disease which shares some characteristics with malignancy like migration and invasion. It has been reported that both Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) and autophagy were upregulated in ectopic endometrium of patients with ovarian endometriosis. However, the crosstalk between HIF-1α and autophagy in the pathogenesis of endometriosis remains to be clarified. Accordingly, we investigated whether autophagy was regulated by HIF-1α, as well as whether the effect of HIF-1α on cell migration and invasion is mediated through autophagy upregulation. Here, we found that ectopic endometrium from patients with endometriosis highly expressed HIF-1α and autophagy related protein LC3. In cultured human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs), autophagy was induced by hypoxia in a time dependent manner and autophagy activation was dependent on HIF-1α. In addition, migration and invasion ability of HESCs were enhanced by hypoxia treatment, whereas knockdown of HIF-1α attenuated this effect. Furthermore, inhibiting autophagy with specific inhibitors and Beclin1 siRNA attenuated hypoxia triggered migration and invasion of HESCs. Taken together, these results suggest that HIF-1α promotes HESCs invasion and metastasis by upregulating autophagy. Thus autophagy may be involved in the pathogenesis of endometriosis and inhibition of autophagy might be a novel therapeutic approach to the treatment of endometriosis.

Keywords: hypoxia, HIF-1α, autophagy, invasion, endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis, a common contributor for infertility and chronic pelvic pain, is characterized by the extra-uterine growth of endometrial glands and stroma (Giudice and Kao 2004). Among the numerous theories regarding the pathogenesis of endometriosis, the most commonly accepted one is Sampson’s hypothesis of retrograde menstruation, which states that the endometrial tissues shed from uterine cavity during menses exit the uterus through fallopian tubes (Sampson 1927). Although endometriosis is generally assumed to be a benign disease, it has the similar malignant biological behavior like cancer, such as aggressive migration and invasion (Bassi, et al. 2009a), which is crucial for the development of endometriosis.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that hypoxia played important roles in endometriosis (Hsiao, et al. 2014, Lin, et al. 2012). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1, a heterodimeric transcriptional factor mediating the cellular response to hypoxia, is made up of α and β subunits (Majmundar, et al. 2010). Unlike the constitutively expressed HIF-1β, HIF-1α is highly regulated by cellular oxygen tension. Under normoxic conditions, the HIF-1α subunit is rapidly degraded; whereas under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α is stabilized and translocated to the nucleus where it heterodimerized with HIF-1β to cause target gene transcription (Semenza 2009). HIF-modulated genes have been identified to contribute to invasion, angiogenesis and autophagy of different types of tumor cells (Cheng, et al. 2013, Zhao, et al. 2010). Moreover, the expression level of HIF-1α in serum and ectopic endometrium of patients with endometriosis was elevated (Karakus, et al. 2016, Wu, et al. 2007).

Autophagy is an evolutionary conserved process responsible for the bulk degradation of cytoplasmic components, such as long-lived proteins and damaged organelles (Hale, et al. 2013). During autophagy, double-membrane vesicles surround and deliver the cytoplasmic material to lysosomes for degradation (Yang and Klionsky 2010). Autophagosomes formation requires two ubiquitin-like protein conjugation pathways: autophagy-related gene (Atg)12-Atg5 conjugation system and the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 beta (LC3) - lipid phosphotidylethanolamine (PE) conjugation system (Ohsumi and Mizushima 2004). LC3, a mammalian homolog of yeast Atg8, is known to be present on autophagosomes, and the conversion of LC3 I to LC3 II is a widely used marker to monitor this process (Mizushima, et al. 2010). Beclin1 (also named ATG6) is another key regulator, which play essential roles in autophagy activation (Kang, et al. 2011). It is now generally accepted that autophagy is a protective mechanism for cells adaptation to stress conditions like hypoxia (Bhogal, et al. 2012, Hu, et al. 2012). Interestingly, autophagy upregulation was observed in ectopic endometrium of patients with ovarian endometriosis (Allavena, et al. 2015). However, it is still unclear whether autophagy was activated in human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs) under hypoxia environment and few studies have elucidated the correlation between HIF-1α and autophagy in the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to investigate: (a) whether expression levels of HIF-1α and autophagy were changed in ectopic endometrium; (b) the molecular mechanism of autophagy activation by hypoxia in human endometrial stromal cells (HESCs); (c) the possible role of autophagy in HIF-1α induced migration and invasion of HESCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval

The tissue samples were obtained with full and informed patient consent. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the local Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science (IORG No: IORG0003571).

Patients and tissue collection

The patients recruited for the study were non-pregnant women of childbearing age (22–48 years) attending the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology between October 2013 and October 2015. All patients had regular menstrual cycles and were not taking any combination hormonal contraception for at least six months prior to surgery. The endometrial samples were collected during the proliferative stage, which was confirmed based on clinical or histologic criteria.

As controls, eleven cases of normal endometrium were obtained from patients with tubal infertility. Ten cases of eutopic endometrium (from another group of women with ovarian endometriosis) and ten cases of ectopic endometrium (from ovarian endometriotic cysts) were obtained from patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery or hysterectomy. All of the ectopic endometrium were classified as revised American Fertility Society stage III or IV (1997). The collected endometrial tissues was divided into two parts: the first part was used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis according to the criteria of Noyes et al (Noyes, et al. 1975), and the second part was used for western blot analysis. Besides, another thirty cases of eutopic endometrium of patients with endometriosis were collected for isolation and cultivation of endometrial stromal cells. The endometrial tissues were collected using the Nowak’s curette just before the surgical procedure, and immediately transported to the laboratory.

Immunohistochemistry

All fresh surgical specimens were fixed in 10 % formaldehyde for 24 hours, then embedded in paraffin blocks. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded endometrial tissues were sectioned at 5 μm and mounted on alcohol-cleaned glass slides. The sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated by passing through a graded series of alcohol to water, and antigen retrieval was performed by heating sections in citrate buffer at pH 6.0. Endogenous non-specific peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the section in 50% ethanol solution containing 3% H2O2 for 30 min. The sections were sequentially blocked with protein block for 30 minutes followed by blocking in bovine serum albumin for 30 min and then incubated with primary antibodies against HIF-1α (1:1000; Affinity, USA) and LC3B (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS, the sections were incubated with peroxidase-labelled anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Wuhan Boster Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) for 30 min. Finally, all slides were incubated with DAB-Substrate (Beyotime, China) and counterstained in haematoxylin before dehydrated and mounted. After the immunohistochemical analysis, IPP software (image-pro plus 6.0) was used to analyze the optical density of the representative images (see Supplemental Table. 1).

Isolation and culture of human endometrial stromal Cells (HESCs)

The collected tissues were washed with PBS for three times, then minced into 1mm pieces with a sterile surgical scissors and digested in PBS containing 2 mg/mL of type II collagenase (0.1%, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 45–60 minutes with constant agitation. Stromal cells were isolated from the epithelial cells and debris by use of 150 and 37.4μm sieves, and the filtered stromal cells were plated in T25 flasks. After overnight culture, the stromal cells attached, and the contaminated blood cells and debris that were suspended in the culture medium were removed by aspiration, and the stromal cells were washed with PBS. The stromal cells were subsequently cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s/F12 medium (DMEM/F12; HyClone) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (HyClone) in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The purity of isolated stromal cells was >95% and stromal cells were contaminated by less than 1% of epithelial cells, as determined by diffuse and strong cytoplasmic immunostaining for vimentin (diluted 1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and negative cellular staining for E-cadherin (diluted 1:150; Cell Signaling Technology, USA) in immunocytochemistry (see Supplemental Fig. 1). Endometrial stromal cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium with the addition of either 10 mM 3-methyladenine (3-MA) or 500 μM Chloroquine to inhibit autophagy.

Hypoxia treatment

Upon reaching confluence, the endometrial stromal cells (4 × 105) were seeded in 60 mm culture dishes and fresh medium was used to keep the cells healthy by providing fresh nutrients before hypoxia treatment. The culture dishes were incubated in a modular incubator chamber (Thermo Scientific, USA) containing humidified hypoxic air (1% O2, 5% CO2, 94% N2) for 0, 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours at 37 °C. Stromal cells cultured under normoxic condition (20% O2, 5% CO2 and 75% N2) were used as controls.

Hypoxia treated cells were collected at the indicated time points and prepared for Western blot analysis. After cultured under hypoxic conditions for 24 hours, monodansylcadaverine (MDC) staining and acridine orange (AO) staining was performed to detect the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles. In addition, the ultrastructure of autophagosomes in hypoxia treated cells was observed by transmission electron microscopy.

Immunocytochemical staining of HESCs

The immunocytochemistry were performed to detect mesenchymal marker vimentin and epithelial marker E-cadherin. HESCs were plated into a 6-well plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and grown until approximately 80% confluent. The medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times in PBS. After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 15 min, the cells were soaked in 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma, Belgium) for 15 min to increase their permeability to antibodies. For blocking unspecific binding site of antigens, the cells were rinsed with 10% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 60 min, and incubated overnight at 4°Cwith the primary antibodies that mentioned previously. The cells were then washed three times in PBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for two hours, followed by washing in PBS. Images were collected using an Eclipse TE2000-S microscope system (Nikon UK Ltd, Surrey) and Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics UK, Berkshire).

Protein extraction and Western Blot analysis

Collected endometrial tissues and cultured HESCs were washed three times with ice cold PBS and lysed in radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) containing protease inhibitors (Sigma, USA). The cells were scraped in this lysis buffer, kept on ice for at least 30 minutes, centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes, and diluted in 5x sample buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, China) was used to determine the protein concentrations. Equal amounts of proteins (30ug) were mixed with the sample buffer (4% SDS, 10% beta-mercaptoethanol, and 20% glycerol in 0.125 M Tris, pH 6.8) containing bromophenol blue, and were boiled for10 minutes at 95°C. The samples were loaded and separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels (PAGE) with running buffer. The proteins separated by SDSPAGE were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P transfer membrane). The membranes were incubated with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 hours, and were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: HIF-1α (diluted 1:1000; Affinity, USA), LC3B (diluted 1:1000,Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Beclin1 (diluted 1:1,000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and GAPDH (diluted 1:1000; Affinity, USA). The membranes were washed three times with TBST for 15 minutes, and then incubated with an HRP-labeled secondary Ab at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were washed again and treated with ECL-Western blot detecting reagent (Millipore. USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The protein bands intensity were observed by imaging system (Gel Doc 2000; Bio-Rad, USA) and analysis with Image J software (NIH) (version 1.5, USA).

Acridine Orange (AO) staining assay

Acridine orange (AO) is a fluorescent cationic dye used to detect acidic vesicular organelles (lysosomes) within cells. It can interact with DNA emitting green fluorescence or accumulate in acidic organelles in which it becomes protonated forming aggregates that emit bright yellow-to-orange fluorescence (Pierzynska-Mach, et al. 2014). The cytoplasm and nucleus showed bright green fluorescent signal, while the acidic vesicular organelles showed bright yellow-to-orange fluorescent signal. Briefly, 5 × 104 cells were stained with 1 μg/mL acridine orange (AO) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in the dark. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS for three times and immediately observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX51, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The autophagy was measured by quantification of the rate of AO positive stained vacuoles in five random fields (a field containing at least 40 cells) for each experimental condition.

Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) staining assay

To detect autophagic vacuoles, monodansylcadaverine (MDC), a fluorescent dye known as specific marker for autophagic vacuoles, was used. 5 × 104 cells were grown on coverslips in 6-well plate, and cultured under hypoxic conditions for the indicated time, followed by washing three times with PBS and fixed in 10% formalin solution for 10 min. Then cells were stained with 0.05 mM MDC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 15 minutes at 37°C in the dark. The following procedures were the same as AO staining. The autophagy was measured by quantification of the rate of MDC positive stained vacuoles in five random fields (a field containing at least 40 cells) for each experimental condition.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To identify autophagosomes at the ultrastructural level, HESCs were cultured under hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 24h. After the indicated treatment, HESCs were washed three times with PBS and incubated with trypsin for 2 min. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets were suspended and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight, and then washed in 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) twice for 15 min each and post-fixed with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 3 hours. After being washed by 0.1 M Na-phosphate buffer, the cells were then dehydrated at 25°C with a graded series of ethanol and gradually infiltrated with epoxy resin mixture (812 resin embedding kit). The samples were sequentially polymerized at 37°C for 12h, 45°C for 12 h, and 60°C for 24 h. Ultrathin sections (50–70 nm) were cut by using LKB microtome and mounted on single-slot copper grids. THE sections were subjected to double staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a transmission electron microscope (Philips CM-120).

Cell transfection assay

HIF-1α siRNA, Beclin1 siRNA and scrambled negative control siRNA were purchased from Shanghai GenePharma (China). The siRNA sequences included HIF-1α siRNA (sense, 5′-GCUGGAGACAAUCAUAUTT-3′, antisense, 5′-AUAUGAUUGUGUCUCCAGCTT-3′), Beclin1 siRNA (sense, 5′-CGGGAAUACAGUGAAUUUATT-3′, antisense, 5′-UAAAUUCACUGUAUUCCCGTT-3′) and scrambled negative control siRNA (sense, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′; antisense, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′). HIF-1α overexpression plasmid (pG/CMV/HIF-1α/IRES/EGFP) and negative control (NC) plasmid were purchased from Gemma Pharmaceutical Technology (China). For knockdown, HESCs (2x105 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to 60–80% confluence, followed by transfected with the above plasmids or siRNA using lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transfection mixture was replaced 6 hours later with DMEM/F-12 with 20% FBS. Then HESCs were incubated in normoxic or hypoxic conditions for another 24 hours and subjected to western blot analysis and GFP-LC3 adenoviral vector transfection.

Autophagy detection using GFP –LC3 adenoviral vector

The indicated cells were seeded on coverslips in a 24-well plates and allowed to reach 50% – 70% confluence at the time of transfection. GFP-LC3 adenoviral vectors were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Adenoviral infection was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HESCs were incubated in growth medium with the adenoviruses at a MOI of 50 for 24 h at 37 °C. The cells in the control group and HIF-1α overexpression group were cultured under normoxic condition for another 24 h; the cells in the siHIF-1α and hypoxia groups were cultured under hypoxic condition for another 24h. After treatment, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS for three times and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS and cover slips were mounted on the slides. Autophagy was observed immediately observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA). Autophagic level was determined by evaluating the number of GFP –LC3 puncta (puncta/cell were counted).

Immunofluorescence assay

The indicated cells were seeded and grown on coverslips in a 6-well plates. The cells in the control group and HIF-1α overexpression group were cultured under normoxic condition for 24 h; the cells in the siHIF-1α and hypoxia groups were cultured under hypoxic condition for 24h. After treatment, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Then cells were incubated with 5% BSA (bovine serum albumin) for 1 hour to block non-specific binding at room temperature and incubated with a LC3B antibody (1:300; Abcam, USA) at 4°C overnight. The next day, the cells were incubated with goat FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 2 hours at dark room and then incubated with 4′, 6-diamidino-2 phenylindole (DAPI) for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the cells were washed three times with PBS, and immediately observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc, Center Valley, PA).

Transwell migration and invasion assays

Migration and invasion assays were performed using transwell 24-well plates with 8-μm diameter filters (Corning Costar, Tewksbury, MA, USA). For invasion assay, microfilters were precoated with 40 μl of working matrigel (1:3 diluted with FBS-free DMEM) (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) and were matained at 37°C for at least 5 h. The following procedures were the same for migration and invasion assays. Approximately 2x105cells in 200μl of serum-free medium containing 500 μM chloroquine or 10 mM 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) were loaded in the upper matrigel coated chamber and 500μl of medium containing contain 20% fetal bovine serum was placed in the lower chamber. The cells cultured in normoxic condition were used as the control groups. The cells cultured under hypoxic condition with or without 500 μM chloroquine or 10 mM 3-MA were used as experimental groups. To evaluate the migration potential, cells were allowed to migrate towards medium over a period of 24h. For the invasion assay, after seeded, cells were allowed to invade for 48h. After the indicated treatment, cells were fixed in methanol for 20 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for another 20 min. Then the cells on the upper surface of the filters were wiped off with cotton swabs, and the filters were washed three times with PBS. The cells on the underside of the filters were observed and counted under an inverted microscope at x200 magnification. Duplicate wells per condition were tested in three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis software Graphpad Prism (version 6.01; GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA) was used to carry out the statistical analyses. The Kruskal–Wallis test were used for statistical significance of differences in variables with non-normal distribution. The Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test were used to measure comparisons between groups in normal distribution. All data sets were shown as mean ± standard deviations (SD) from at least three independent experiments. Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

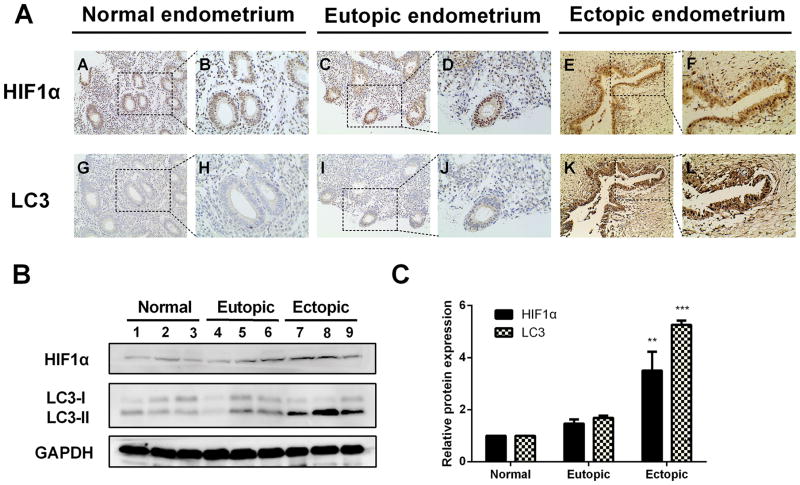

The expression levels of HIF1α and LC3 protein were elevated in ectopic endometrium of endometriosis patients

To determine the autophagy activity in endometriosis tissues and its relationship with HIF-1α, immunohistochemical staining was performed to detect the expression of HIF-1α and autophagy marker LC3. Representative staining examples are shown in Figure 1 and immunostaining score are depicted in Supplemental Table 1. As shown inFigure. 1A, HIF-1α was expressed in the nuclei of epithelial and stromal cells, while LC3 was localized within the cytoplasm of both cells. The expression levels of HIF-1α and LC3 in the ectopic endometrium were significantly greater than those in normal endometrium and eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis. HIF-1α expression levels in ectopic endometrium significantly correlated with the levels of LC3 (Supplemental Tab.1). Moreover, western blot analysis revealed the similar trend for HIF-1α and LC3-II proteins expression (Fig. 1B and 1C). However, no significant difference was observed between normal endometrium and eutopic endometrium from the patients with endometriosis (Fig. 1B and 1C). Taken together, these results suggested that autophagy is upregulated in ectopic endometrium and HIF-1α may play a vital role in this event.

Figure 1. The expression levels of HIF1α and LC3 protein were elevated in ectopic endometrium of endometriosis patients.

(A) Representative immunohistochemical images of HIF-1α and LC3 protein localization in normal endometrium (A, B, G, H), eutopic endometrium (C, D, I, J) and ectopic endometrium (E, F, K, L). Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200× (left panels) and 400× (right panels) respectively. (B) Representative western blots of HIF-1α and LC3 protein from normal endometrium, eutopic endometrium and ectopic endometrium. (C) The protein expression levels were quantified by the fold difference using Image J software and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by Student’s t-test).

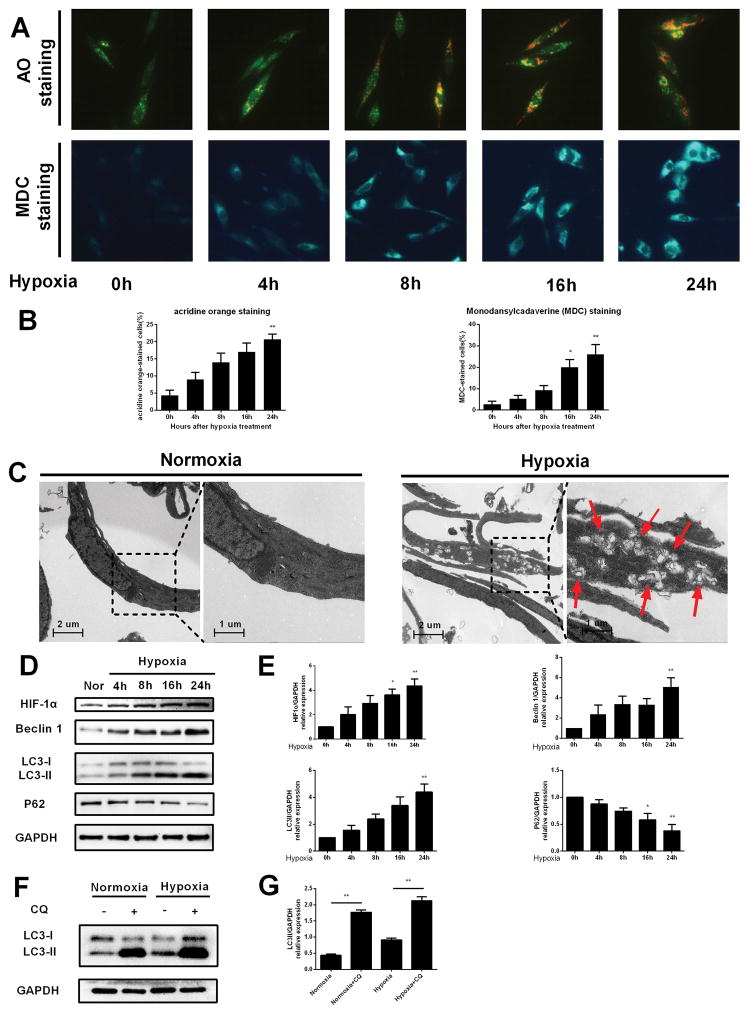

Hypoxia induced autophagy in HESCs

To determine whether autophagy is activated by hypoxia stress, we performed a series of investigations to evaluate it. At first, acridine orange (AO) and monodansylcadaverine (MDC) staining were used to detect acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs), which reflecting autophagosomes. As shown in Figure. 2A and 2B, exposure of HESCs to hypoxic conditions resulted in accumulation of autophagic vacuoles in a time dependent manner. Electron microscopy remains to be one of the most accurate methods to detect autophagy and quantify autophagic accumulation (Swanlund, et al. 2010). The ultrastructural results showed that numerous cytoplasmic phagolysosomes were present after hypoxia treatment (Fig. 2C, right panel). However, few phagolysosomes was observed in the control group (Fig. 2C, left panel). Furthermore, western blot analysis displayed that the protein expression levels of HIF-1α, Beclin 1 and LC3-II and were increased in a time dependent manner after hypoxia treatment (Figure. 2D and 2E). As the elevation of LC3 protein level could be resulted from increased autophagosomes formation or decreased autophagosome degradation (Mizushima and Yoshimori 2007), autophagy flux was evaluated in the presence and absence of lysosomal degradation inhibitor chloroquine. As shown in Figure. 2F and 2G, a blockade of the autophagosome-lysosome fusion by using chloroquine significantly increased the accumulation of endogenous LC3-II protein, and hypoxia apparently augmented this effect, indicating that hypoxia-induced elevation of LC3-II is due to autophagy activation, rather than blockage of lysosomal degradation. Altogether, these results demonstrate that hypoxia is able to induce autophagy in HESCs.

FIGURE 2. Hypoxia induced autophagy in HESCs.

(A) Representative images of HESCs treated with hypoxia for 0, 4, 8, 16 and 24 h, respectively and then cells were stained with acridine orange and MDC. (B) The percentage of cells stained for acridine orange or MDC in (A) were quantified. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by the Kruskal–Wallis test).(C) Representative images of transmission electron microscopy performed on HESCs receiving hypoxic treatment as described in the materials and methods. Transmission electron Microscopy photographs of HESCs cultured under normoxic conditions for 24 hours (left panel) or hypoxiac conditions for24 hours (right panel). The red arrows point to autophagosomes (scale bar, 1 μm).(D) HESCs were incubated under hypoxic conditions for 0, 4, 8, 16 and 24 hours and then lysed and analyzed by Western blots to determine the expression levels of HIF-1α, Beclin1 and LC3. (E) The quantitative comparison of the fold difference in the expression of HIF-1α, Beclin1 and LC3 protein. Total protein levels were normalized to GAPDH levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by the Kruskal–Wallis test).(F) Representative Western blots of LC3 protein under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, in the presence or absence of Chloroquine.(G) The expression levels of LC3 protein were quantified by Image J software and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by the Kruskal–Wallis test).

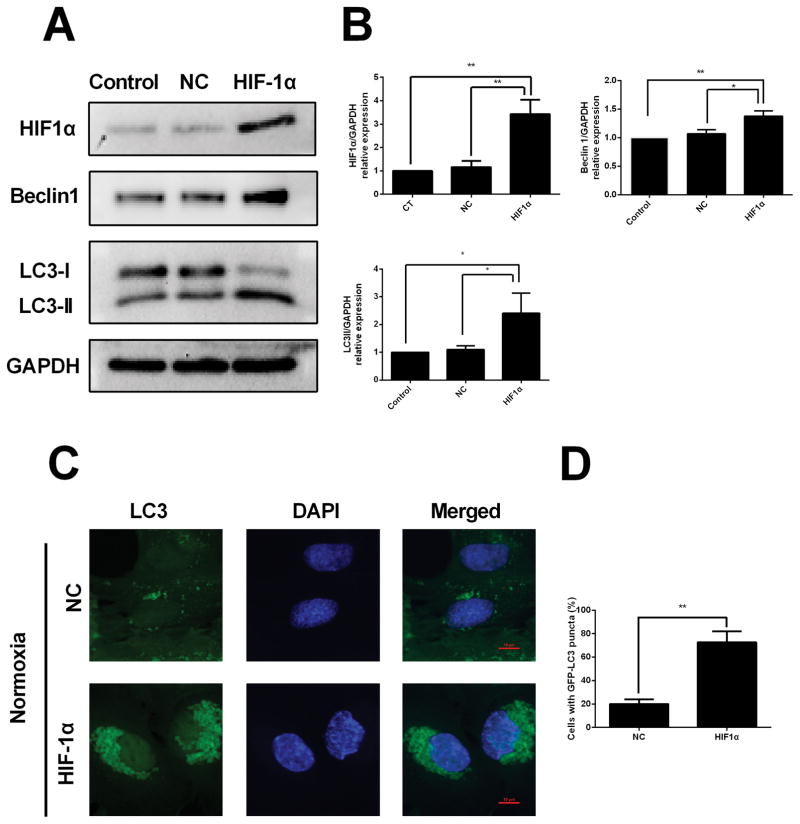

HIF-1α overexpression induces autophagy under normoxiac condition

To examine whether HIF-1α has an effect on autophagy, HESCs were transfected with a HIF-1α expression plasmid under normoxia conditions. Western blot results showed that HIF-1α overexpression caused increased expression levels of HIF-1α and Beclin1 and LC3, (Fig. 3A and 3B). In addition, we found that compared with the negative control group, the HESCs transfected with HIF-1α overexpression plasmid showed typically dense accumulation of GFP-LC3 puncta in the perinuclear region under normoxia condition (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3. HIF-1α overexpression induces autophagy under normoxic conditions.

(A) Representative western blots of HIF-1α, Beclin1 and LC3 protein in HESCs transfected with negative control (NC) plasmid or HIF-1α expression plasmid under normoxic condition. (B) The protein expression levels were quantified by Image J software and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). **(C)**Detection of GFP-LC3 puncta indicative of autophagy in HESCs transfected with negative control (NC) plasmid or HIF-1α expression plasmid under normoxic condition for 24 hours. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Photographs were taken at magnifications of 1600×. (D) Quantification of the percentage of cells displaying punctate GFP-LC3 using ImageJ. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by Student’s t test).

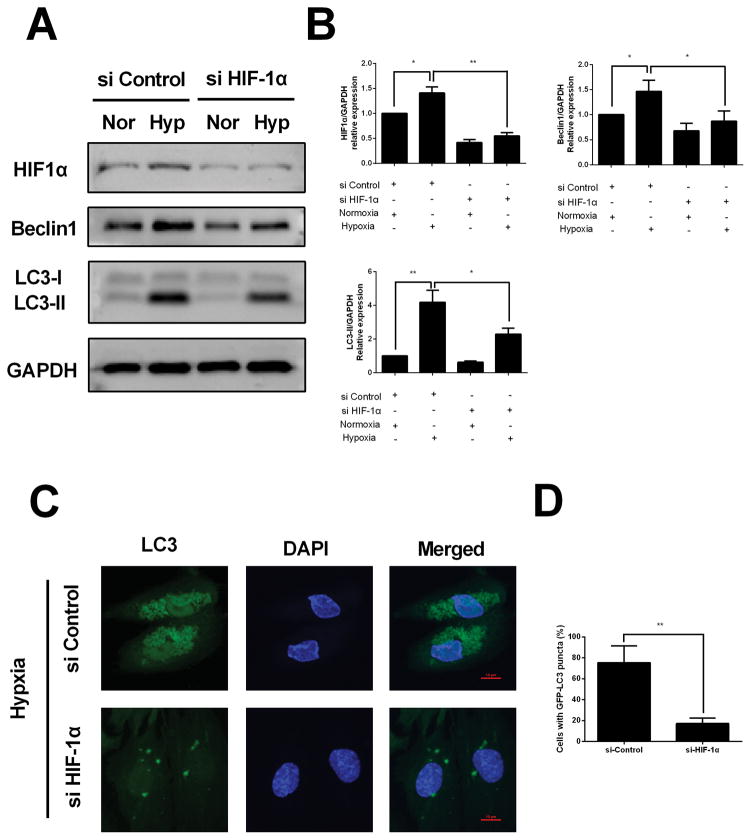

Knockdown of HIF-1α interferes with hypoxia-induced autophagy in HESCs

To further corroborate the role of HIF-1α in hypoxia induced autophagy, HESCs were transfected with specific siRNA targeting HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions. Compared with HESCs transfected with control siRNA, decreased expression of HIF-1α and Beclin1 and LC3 were observed in HESCs transfected with HIF-1α siRNA under hypoxia condition (Fig. 4A and 4B). Moreover, GFP-LC3 puncta accumulation was significant decreased in HESCs transfected with HIF-1α siRNA compared to that of negative control group under hypoxia condition (Fig. 4C). These, together with the above results, suggest that autophagy upregulation under hypoxic condition was dependent on the status of HIF-1α.

FIGURE 4. Knockdown of HIF-1α interferes with hypoxia-induced autophagy in HESCs.

(A) Representative western blots of HIF-1α, Beclin1 and LC3 protein in HESCs transfected with scrambled control siRNA or HIF-1α specific siRNA in the presence or absence of hypoxia. (B) The protein expression levels were quantified by Image J software and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). (C)Detection of GFP-LC3 puncta indicative of autophagy in HESCs transfected with scrambled control siRNA or HIF-1α specific siRNA under hypoxia condition for 24 hours. Photographs were taken at magnifications of 1600×.(D) Quantification of the percentage of cells displaying punctate GFP-LC3 using ImageJ. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by Student’s t test).

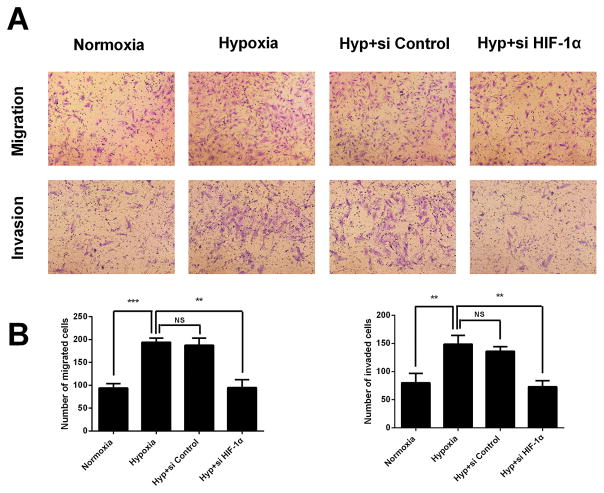

Hypoxia enhances the migration and invasion of the HESCs in a HIF-1α dependent manner

To explore the effect of hypoxia on cellular motility, transwell migration and invasion assays were conducted. Treatment with hypoxia significantly enhanced the migration and invasion ability of HESCs, when compared with the untreated control cells (Figure. 5A and 5B). On the contrary, the hypoxia triggered invasive ability could be attenuated by HIF-1α siRNA. The number of cells that crossed the lower chamber decreased upon HIF-1α siRNA treatment (Figure. 5A and 5B). These results demonstrated hypoxia can augment the ability migration and invasion of HESCs in vitro, and this event was dependent on HIF-1α.

FIGURE 5. Hypoxia enhances the migration and invasion of the HESCs via HIF-1α.

(A) Representative photographs of migration and invasion of hypoxia treated, hypoxia with si-control cotreated or hypoxia with si-HIF-1α cotreated HESCs. (B) Quantitative assessment of the number of HESCs migrated and invaded to the lower chamber. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200×.

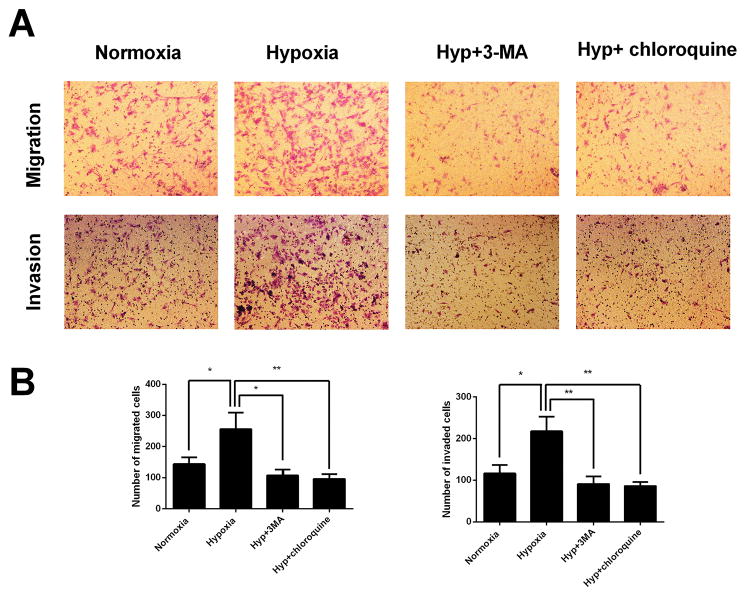

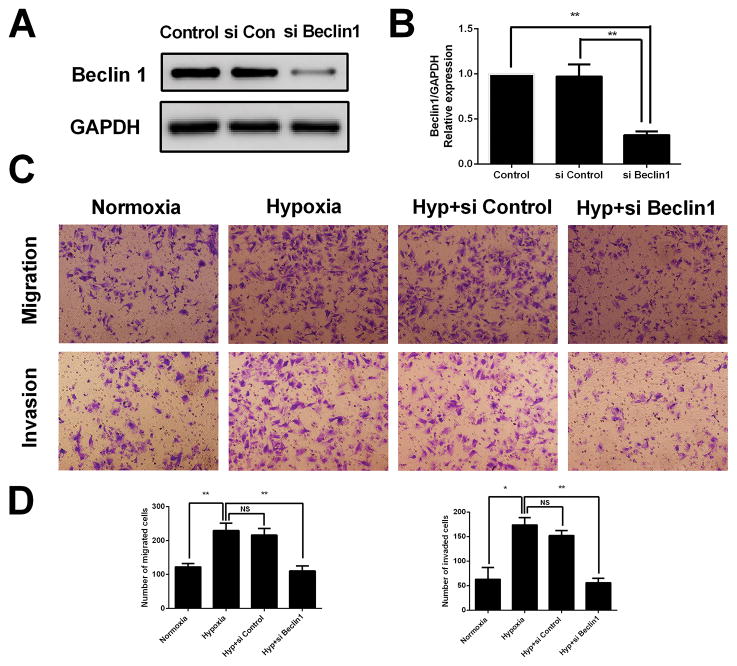

Hypoxia-induced HESCs migration and invasion is attenuated by autophagy inhibition

To examine whether autophagy has an effect on migration and invasion of HESCs under hypoxia condition, transwell migration and invasion assays were conducted. Here, two types of autophagy inhibitors, 3-MA and Chloroquine, were used to inhibit autophagy. 3-MA inhibits autophagy at early stage by blocking autophagosome formation via the inhibition of type III Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases, involved in the initiation of autophagosome formation (Wu, et al. 2010). Chloroquine inhibits autophagy at late stage by inhibiting lysosomal proteases and preventing autophagosome-lysosome fusion (Geng, et al. 2010). Our data revealed that HESCs treated with hypoxia displayed significantly increased migration and invasion abilities comparison to those untreated, which was nevertheless markedly reversed by the addition of 3-MA or chloroquine (Fig 6A and 6B). The pro-invasion role of autophagy in HESCs was further validated by genetically impairing the autophagy pathway using siRNA to Beclin1. As shown in Fig 7A and 7B, the Beclin1 siRNA suppressed expression of the Beclin1 protein. Similar to autophagy inhibition by 3-MA and Chloroquine, the genetic inhibition of autophagy by Beclin1 siRNA also attenuated HESCs migration and invasion abilities under hypoxia condition (Fig 7C and 7D). Collectively, these results demonstrated that autophagy facilitates the hypoxia triggered migration and invasion of HESCs in vitro.

FIGURE 6. Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA and Chloroquine attenuates hypoxia induced HESCs migration and invasion.

(A) Representative photographs of migration and invasion of control, hypoxia treated, hypoxia with 3-MA cotreated or hypoxia with Chloroquine cotreated HESCs. (B) Quantitative assessment of the number of HESCs migrated and invaded to the lower chamber. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200×.

FIGURE 7. Genetic inhibition of autophagy attenuates hypoxia induced HESCs migration and invasion.

(A) Representative western blots of Beclin1 protein in HESCs transfected with scrambled control siRNA or Beclin1 specific siRNA.(B) The protein expression levels were quantified by Image J software and normalized to GAPDH protein levels. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). **(C)**Representative photographs of migration and invasion of control, hypoxia treated, hypoxia with si-control cotreated or hypoxia with si-Beclin1 cotreated HESCs. (D) Quantitative assessment of the number of HESCs migrated and invaded to the lower chamber. The data are presented as the means ± SD from at least three independent experiments (*p<0.05;**p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by one-way ANOVA). Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200×.

Discussion

Although endometriosis is recognized as a benign disease, its behavior is characterized by certain biological features that also are seen in malignancy (Bassi, et al. 2009b). The migration, invasion and angiogenesis of viable endometrial tissues outside the uterine cavity is a crucial step for the progression of endometriosis (Moggio, et al. 2012). Sampson’s retrograde menstruation hypothesis is the most widely accepted theory. However, this theory does not fully explain why most women suffer from retrograde menstruation but only 10 percent of them finally develop endometriosis. Researchers have found that other factors like local hypoxia microenvironment may contributes to the development of endometriosis. When shed endometrial tissue fragments retrogrades to the pelvic cavity, the first stress faced is the local altered hypoxic microenvironment. Accumulating evidence reported that HIF-1α was upregulated in ectopic endometrium and possibly involved in the invasion process of HESCs (Filippi, et al. 2016, Lu, et al. 2014, Zhan, et al. 2016). Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of HIF-1α regulated endometrial cells migration and invasion is helpful for treatment of this disease.

Autophagy is important in keeping cellular homeostasis, and its dysregulation is closely linked to numerous human pathophysiological processes, including cancer, myopathy, neurodegeneration disease (Levine and Kroemer 2008). Stressful conditions, like hypoxia, can trigger the activation of autophagy (Wu, et al. 2015b). Recently, regulation of autophagy by HIF-1α has been reported. Hypoxia leads to HIF-1α stabilization, which subsequently activate the downstream gene BNIP3 that competes with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL for interaction with Beclin to trigger autophagy (Bellot,et al. 2009). Autophagy is generally considered as a mechanism of cellular protection. In addition, autophagy has also been shown to be involved in modulating cancer cell motility and invasion (Mowers, et al. 2016). For example, autophagy could facilitates TLR3 and TLR4-triggered invasion of lung cancer cells (Zhan, et al. 2014) and contributes to salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cells invasion under hypoxia environment (Wu, et al. 2015a). In recent years increasing research efforts have investigated the possible regulatory mechanism of autophagy in hypoxia triggered cell migration. Autophagy induction during intermittent hypoxia could facilitates the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cell through activation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Zhu, et al. 2014). Moreover, autophagy upregulated by HIF-1α overexpression could supports extra villous trophoblasts invasion by supplementation of cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Yamanaka-Tatematsu, et al. 2013). Interestingly, autophagy activation in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in attenuated invasiveness through HIF-1α degradation by autophagic pathway (Indelicato, et al. 2010). These apparently disparate conclusions in the field suggests that autophagy may play more complicated roles in tumor invasion, which will be an interesting area for future study.

Previous study indicated that autophagy is upregulated in ovarian endometriosis and possibly contributes to survival of endometriotic cells and to lesion maintenance in ectopic sites (Allavena,et al. 2015). However, there have been controversial results regarding the expression level of autophagy in endometriosis. JongYeob Choi_et al._ reported that autophagy level was decreased in ectopic endometrium together with activation of p70S6K phosphorylation (signature of mTOR activation) (Choi, et al. 2014). These contrasting results may be explained by the fact that a complex signaling networks involved in the regulation of autophagy. The study have found that akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling was activated in ovarian endometriosis (Leconte, et al. 2011, Yagyu, et al. 2006). As a negative regulator of autophagy, mTOR activation may resulted in autophagy inhibition in endometriosis. In fact, besides the canonical PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling (Wu,et al. 2009), autophagy can be also induced through non-canonical signaling like ammonia pathway (Polletta, et al. 2015) and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent pathways (Bellot, et al. 2009). Based on the abovementioned correlations between HIF-1α, autophagy and endometriosis, we hypothesized that autophagy upregulation in endometriosis may due to local hypoxia and autophagy play a role in HIF-1α induced HESCs migration and invasion. To elucidate these questions, we designed and conducted a series of investigations.

In our present study, our results from immunohistochemical staining and western blots showed that both HIF-1α and autophagy related protein LC3 expression level were elevated in ectopic endometrium compared with normal and eutopic endometrium of endometriosis patients, which indicated that autophagy was upregulated and HIF-1α may correlated with this event. After hypoxia treatment for different time points, the protein expression level of HIF-1α, Beclin1 and LC3 were upregulated. Meanwhile, increased autophagic vacuoles and autophagosome accumulation were observed under hypoxic conditions. To elucidate the regulatory role of HIF-1α on autophagy, we transfected HESCs with HIF-1α overexpression plasmid or HIF-1α siRNA. The results showed that overexpression of HIF-1α resulted in upregulated autophagy under normoxic condition and HIF-1α siRNA abrogated hypoxia induced autophagy. Furthermore, in order to investigate the effect of HIF-1α and autophagy on cell migration and invasion, transwell assays were performed. We observed that hypoxia was able to enhance migration and invasion of HESCs, while transfected with HIF-1α siRNA reversed this effect, suggesting that hypoxia promotes HESCs cell migration and invasion through HIF-1α. Furthermore, the application of autophagy inhibitors and specific Beclin1 siRNA significantly reversed the hypoxia-stimulated migration and invasion of HESCs.

There are three limitations in the present study: (a) the sample size is relatively small; (b) the expression of autophagy has not been detected in different phases of the menstrual cycle; and (c) the exact molecular mechanisms underlying autophagy in HESCs invasion under hypoxia environment remains to be established. Thus, future research is needed to gain deeper insight into these questions.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in this study that HIF-1α is able to enhance the migration and invasion of HESCs through upregulating autophagy. It is worth noting that autophagy inhibitor Chloroquine has been applied to a series of clinical trials targeting malignant diseases like melanoma (Rangwala, et al. 2014) and lung cancer (Goldberg, et al. 2012). Moreover, a study using murine endometriosis model revealed that inhibition of autophagy by hydroxychloroquine effectively promotes apoptosis of human endometriotic cells and decreases the number of endometriotic lesions (Ruiz, et al. 2016). Taken together, these findings reinforce the view that inhibition of autophagy might act as a therapeutic tool in the prevention and treatment of endometriosis.

Supplementary Material

01. SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1.

Immunocytochemistry microscopy staining of (A) E-cadherin and (B) Vimentin. Blue signal represent nuclear DNA staining by DAPI.

02. SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 2.

Representative immunofluorescence image of LC3 in HESCs transfected with negative control (NC) plasmid or HIF-1α expression plasmid under normoxic condition for 24 hours. Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200× (left panels) and 800× (right panels) respectively. Blue signal represent nuclear DNA staining by DAPI.

03. SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1.

Immunostaining score for HIF-1α and autophagy marker LC3. All data are expressed as mean±SD. Statistical significance (One way ANOVA analysis).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81471439 to Y Liu.) and the NIH Award (Grant NIH HD076257 to ZB Zhang).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- 1997 Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 67:817–821. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allavena G, Carrarelli P, Del Bello B, Luisi S, Petraglia F, Maellaro E. Autophagy is upregulated in ovarian endometriosis: a possible interplay with p53 and heme oxygenase-1. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1244–1251.e1241. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi MA, Podgaec S, Dias JA, Júnior, Sobrado CW, Abrão MS. Bowel endometriosis: a benign disease? Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009a;55:611–616. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302009000500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi MA, Podgaec S, Dias JA, Junior, Sobrado CW DAF N. Bowel endometriosis: a benign disease? Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2009b;55:611–616. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302009000500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2570–2581. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00166-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogal RH, Weston CJ, Curbishley SM, Adams DH, Afford SC. Autophagy a cyto-protective mechanism which prevents primary human hepatocyte apoptosis during oxidative stress. Autophagy. 2012;8:545–558. doi: 10.4161/auto.19012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JC, Klausen C, Leung PC. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha mediates epidermal growth factor-induced down-regulation of E-cadherin expression and cell invasion in human ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;329:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Jo M, Lee E, Kim HJ, Choi D. Differential induction of autophagy by mTOR is associated with abnormal apoptosis in ovarian endometriotic cysts. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:309–317. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi I, Carrarelli P, Luisi S, Batteux F, Chapron C, Naldini A, Petraglia F. Different Expression of Hypoxic and Angiogenic Factors in Human Endometriotic Lesions. Reprod Sci. 2016;23:492–497. doi: 10.1177/1933719115607978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y, Kohli L, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Chloroquine-induced autophagic vacuole accumulation and cell death in glioma cells is p53 independent. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:473–481. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. The Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Supko JG, Neal JW, Muzikansky A, Digumarthy S, Fidias P, Temel JS, Heist RS, Shaw AT, McCarthy PO, Lynch TJ, Sharma S, Settleman JE, Sequist LV. A phase I study of erlotinib and hydroxychloroquine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1602–1608. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318262de4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale AN, Ledbetter DJ, Gawriluk TR, Rucker EB., 3rd Autophagy regulation and role in development. Autophagy. 2013;9:951–972. doi: 10.4161/auto.24273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao KY, Chang N, Lin SC, Li YH, Wu MH. Inhibition of dual specificity phosphatase-2 by hypoxia promotes interleukin-8-mediated angiogenesis in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2747–2755. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YL, Jahangiri A, De Lay M, Aghi MK. Hypoxia-induced tumor cell autophagy mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Autophagy. 2012;8:979–981. doi: 10.4161/auto.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indelicato M, Pucci B, Schito L, Reali V, Aventaggiato M, Mazzarino MC, Stivala F, Fini M, Russo MA, Tafani M. Role of hypoxia and autophagy in MDA-MB-231 invasiveness. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:359–368. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakus S, Sancakdar E, Akkar O, Yildiz C, Demirpence O, Cetin A. Elevated Serum CD95/FAS and HIF-1alpha Levels, but Not Tie-2 Levels, May Be Biomarkers in Patients With Severe Endometriosis: A Preliminary Report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leconte M, Nicco C, Ngo C, Chereau C, Chouzenoux S, Marut W, Guibourdenche J, Arkwright S, Weill B, Chapron C, Dousset B, Batteux F. The mTOR/AKT inhibitor temsirolimus prevents deep infiltrating endometriosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:880–889. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Wang CC, Wu MH, Yang SH, Li YH, Tsai SJ. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-20a expression increases ERK phosphorylation and angiogenic gene expression in endometriotic stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1515–1523. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Zhang W, Jiang S, Zou J, Li Y. Effect of oxygen tensions on the proliferation and angiogenesis of endometriosis heterograft in severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggio A, Pittatore G, Cassoni P, Marchino GL, Revelli A, Bussolati B. Sorafenib inhibits growth, migration, and angiogenic potential of ectopic endometrial mesenchymal stem cells derived from patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1521–1530.e1522. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowers EE, Sharifi MN, Macleod KF. Autophagy in cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2016 doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrial biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;122:262–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi Y, Mizushima N. Two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems essential for autophagy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierzynska-Mach A, Janowski PA, Dobrucki JW. Evaluation of acridine orange, LysoTracker Red, and quinacrine as fluorescent probes for long-term tracking of acidic vesicles. Cytometry A. 2014;85:729–737. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta L, Vernucci E, Carnevale I, Arcangeli T, Rotili D, Palmerio S, Steegborn C, Nowak T, Schutkowski M, Pellegrini L, Sansone L, Villanova L, Runci A, Pucci B, Morgante E, Fini M, Mai A, Russo MA, Tafani M. SIRT5 regulation of ammonia-induced autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2015;11:253–270. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1009778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala R, Chang YC, Hu J, Algazy KM, Evans TL, Fecher LA, Schuchter LM, Torigian DA, Panosian JT, Troxel AB, Tan KS, Heitjan DF, DeMichele AM, Vaughn DJ, Redlinger M, Alavi A, Kaiser J, Pontiggia L, Davis LE, O’Dwyer PJ, Amaravadi RK. Combined MTOR and autophagy inhibition: phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine and temsirolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy. 2014;10:1391–1402. doi: 10.4161/auto.29119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Rockfield S, Taran N, Haller E, Engelman RW, Flores I, Panina-Bordignon P, Nanjundan M. Effect of hydroxychloroquine and characterization of autophagy in a mouse model of endometriosis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2059. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422–469. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Regulation of oxygen homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:97–106. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanlund JM, Kregel KC, Oberley TD. Investigating autophagy: quantitative morphometric analysis using electron microscopy. Autophagy. 2010;6:270–277. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.2.10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Huang S, Chen Z, Liu W, Zhou X, Zhang D. Hypoxia-induced autophagy contributes to the invasion of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma through the HIF-1alpha/BNIP3 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2015a doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HM, Jiang ZF, Ding PS, Shao LJ, Liu RY. Hypoxia-induced autophagy mediates cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015b;5:12291. doi: 10.1038/srep12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MH, Chen KF, Lin SC, Lgu CW, Tsai SJ. Aberrant expression of leptin in human endometriotic stromal cells is induced by elevated levels of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:590–598. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YT, Tan HL, Huang Q, Ong CN, Shen HM. Activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway promotes necrotic cell death via suppression of autophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:824–834. doi: 10.4161/auto.9099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, Bauvy C, Huang Q, Wenk MR, Ong CN, Codogno P, Shen HM. Dual role of 3-methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10850–10861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagyu T, Tsuji Y, Haruta S, Kitanaka T, Yamada Y, Kawaguchi R, Kanayama S, Tanase Y, Kurita N, Kobayashi H. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin in postmenopausal ovarian endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1545–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka-Tatematsu M, Nakashima A, Fujita N, Shima T, Yoshimori T, Saito S. Autophagy induced by HIF1alpha overexpression supports trophoblast invasion by supplying cellular energy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan L, Wang W, Zhang Y, Song E, Fan Y, Wei B. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: A promising therapeutic target in endometriosis. Biochimie. 2016;123:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Z, Xie X, Cao H, Zhou X, Zhang XD, Fan H, Liu Z. Autophagy facilitates TLR4- and TLR3-triggered migration and invasion of lung cancer cells through the promotion of TRAF6 ubiquitination. Autophagy. 2014;10:257–268. doi: 10.4161/auto.27162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Chen TT, Xia L, Guo M, Xu Y, Yue F, Jiang Y, Chen GQ, Zhao KW. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 mediates expression of galectin-1: the potential role in migration/invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1367–1375. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wang D, Zhang L, Xie X, Wu Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Su Z. Upregulation of autophagy by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha promotes EMT and metastatic ability of CD133+ pancreatic cancer stem-like cells during intermittent hypoxia. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:935–94. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

01. SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 1.

Immunocytochemistry microscopy staining of (A) E-cadherin and (B) Vimentin. Blue signal represent nuclear DNA staining by DAPI.

02. SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE 2.

Representative immunofluorescence image of LC3 in HESCs transfected with negative control (NC) plasmid or HIF-1α expression plasmid under normoxic condition for 24 hours. Photographs were taken at magnifications of 200× (left panels) and 800× (right panels) respectively. Blue signal represent nuclear DNA staining by DAPI.

03. SUPPLEMENTAL TABLE 1.

Immunostaining score for HIF-1α and autophagy marker LC3. All data are expressed as mean±SD. Statistical significance (One way ANOVA analysis).