Donor CD19-CAR T Cells Exert Potent Graft-versus-Lymphoma Activity With Diminished Graft-versus-Host Activity (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Jul 26.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2017 Jan 9;23(2):242–249. doi: 10.1038/nm.4258

Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a potentially curative therapy for hematological malignancies. However, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and relapse after allo-HSCT remain major impediments. Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) direct tumor cell recognition of adoptively transferred T cells.1–5 CD19 is an attractive CAR target, expressed in most B cell malignancies as well as normal B cells.6,7 Clinical trails using autologous CD19-targeted T cells have shown remarkable outcomes in various B cell malignancies8–15. The use of allogeneic CAR T cells poses a concern of increased GVHD, which however has not been reported in selected patients infused with donor-derived CD19-CAR T cells after allo-HSCT.16,17 To understand the mechanism whereby allogeneic CD19-CAR T cells may mediate anti-lymphoma activity without significant GVHD, we studied donor-derived CD19-CAR T cells in allo-HSCT and lymphoma models in mice. We demonstrate that alloreactive T cells expressing CD28-costimulated CD19-CARs experienced enhanced T cell stimulation, resulting in progressive loss of effector function and proliferative potential, clonal deletion, and significantly decreased GVHD. Concurrently, other CAR T cells present in bulk donor T cell populations retained their anti-lymphoma activity consistent with the requirement for engaging both the TCR and the CAR to accelerate T cell exhaustion. In contrast, first generation and 4-1BB-costimulated CARs increased GVHD. These findings could explain reduced risk of GVHD with cumulative TCR and CAR signaling.

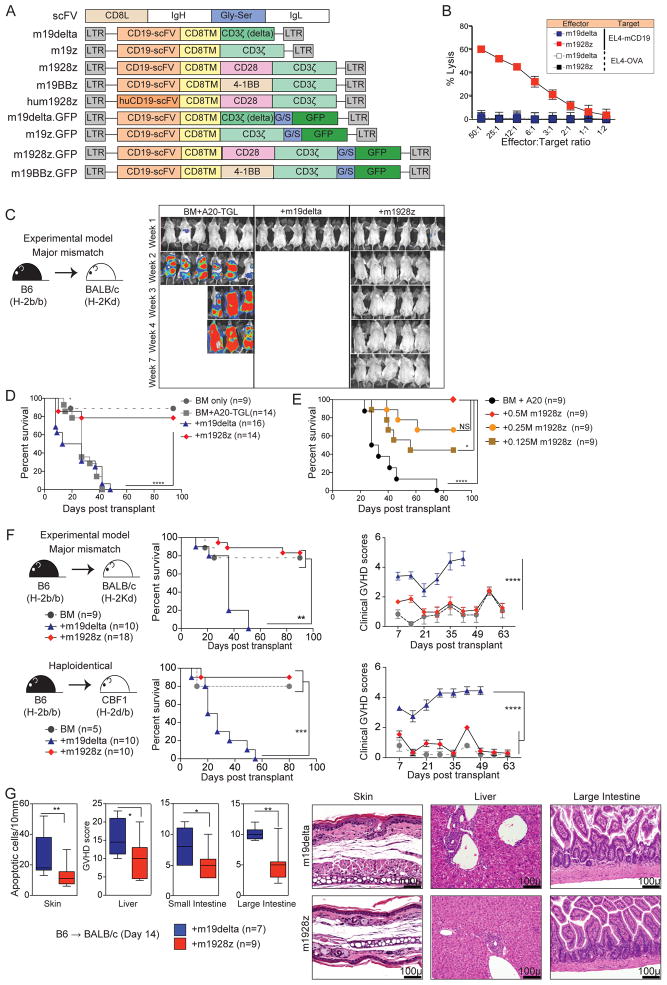

To evaluate the impact of CAR signaling on anti-lymphoma and GVHD activity of allogeneic T cells, we constructed a panel of retroviral vectors encoding CARs targeting mouse-CD19 (Figure 1A). The mouse-1928z (m1928z) CAR encodes murine CD28 linked to CD3-zeta endodomains and is specific for mouse-CD1918. m19delta lacks the CD3-zeta signaling domain, serving as a non-signaling control CAR. m19z lacks a costimulatory signal. m19BBz encodes murine 4-1BB and CD3-zeta endodomains. hum1928z contains a human-CD19-specific scFv and does not cross-react with mouse-CD19. m19delta.GFP and m1928z.GFP are GFP fusion proteins13. CAR expression was verified by flow cytometry (Suppl Figure 1) and m1928z, but not m19delta, T cells specifically lysed CD19-expressing syngeneic targets (Figure 1B). In an MHC-disparate model of allo-HSCT (B6→BALB/c) m1928z and m19delta T cells were compared in mice inoculated with A20-TGL B cell lymphoma to model lymphoma relapse. Recipients of allogeneic m19delta T cells developed lethal acute GVHD, while recipients of only T cell depleted BM allografts died of lymphoma. Strikingly, recipients of m1928z T cells demonstrated reduced tumor growth and mortality due to GVHD, resulting in significantly improved overall survival compared to those treated with m19delta T cells and untreated controls (p<0.0001, Figure 1C and 1D, Suppl Figure 2). We identified a dose-dependent increase in the survival of BALB/c recipients of B6 BM infused with A20 cells when treated with varying doses of m1928z T cells (Figure 1E), demonstrating increasing anti-lymphoma activity without increased GVHD in 0.125–0.5×106/mouse T cell dose range. Transfer of at least 0.5×106 m1928z T cells was required to promote anti-lymphoma activity beyond that conferred by the alloreactive GVL effect mediated by m19delta T cells (Suppl Figure 3).

Figure 1. m1928z T cells eliminate CD19-expressing lymphoma while exerting significantly less GVHD activity.

(A) CD8L = mouse CD8 leader, CD8TM= mouse CD8 transmembrane region, Gly-Ser = glycine-serine linker. Representation of murine CD19-CAR constructs: m19delta (mouse-specific CAR lacking non-functional zeta-chain); m19z (mouse-specific functional CAR, no costimulation); m1928z (mouse-specific functional CAR, CD28-stimulation); m19BBz (mouse-specific functional CAR, 4-1BB costimulation); hum1928z (human-specific functional CAR, mouse CD28 costimulation); m19delta.GFP and m1928z.GFP (CARs with GFP reporter). (B) In vitro cytotoxicity assay using m19delta and m1928z CAR T cells as effectors and EL4-CD19 or EL4-OVA (control). (C, D) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells and inoculated with A20-TGL lymphoma cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta or m1928z T cells per mouse. Tumor growth was monitored by in vivo bioluminescence and images from one of multiple independent experiments are depicted. The BLI images are depicted from one of two experiments (C). Survival was monitored for up to 100 days. Data are representative of two independent experiments (D). (E) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells and inoculated with A20-TGL lymphoma cells. Designated groups were treated with 0.5×106, 0.25×106, or 0.125×106 B6 m19delta or m1928z T cells per mouse. Survival was monitored. The mice treated with B6 m19delta T cells are depicted in Suppl Figure 3 for simplicity. (F) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients (upper panel) and CBF1 recipients (lower panel) were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta or m1928z T cells. Survival and weekly clinical GVHD scores were monitored. Results are pooled from two independent experiments. (G) Skin, liver, small intestine and large intestine were harvested from the recipients on day 14 post-transplant. H&E sections were analyzed for GVHD in a blinded fashion. Results pooled from 2 independent experiments and representative micrographs are shown. Black bar on micrographs indicate a field length of 100 microns. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

The diminished GVHD activity of m1928z T cells in allo-HSCT recipients was confirmed by evaluating the survival and clinical GVHD scores in the absence of tumor (Figure 1F). We performed experiments in acute GVHD models comprising MHC-disparate (B6→BALB/c)19 and haploidentical (B6→CBF1)20 combinations to determine if the inhibition of GVHD by the m1928z T cells was consistent in mice on different genetic backgrounds with heterogeneous alloreactive TCR antigen specificities. Histopathological analyses revealed significantly lower GVHD scores in major GVHD target organs (skin, liver, small and large intestines) of allo-HSCT recipients of m1928z vs. m19delta T in both transplant models (Figure 1G). However, at very high doses of T cells (107 cells), we noted increased mortality in both m1928z and m19delta T cell recipients (Suppl Figure 4), indicating that transfer of large numbers of non-transduced T cells was sufficient to promote comparable GVHD in recipients of m1928z and m19delta T cells. Our findings suggest that GVHD in m1928z T cell recipients may occur as a result of either (1) a high number of non-transduced cells mediating GVHD or (2) excess alloreactive m1928z T cells that direct effector function towards GVHD target organs in the setting of limited numbers of B cells. Importantly, this argues against a mechanism in which alteration of the host environment, for example by B cell depletion by m1928z T cells, dominantly inhibits GVHD. These data are of significance because the current CAR T clinical protocols do not involve post-transduction sorting, and in addition to cytokine release syndrome seen with high doses of CAR T cells, there is an increased risk of GVHD when transferring greater numbers of transferred non-transduced cells21.

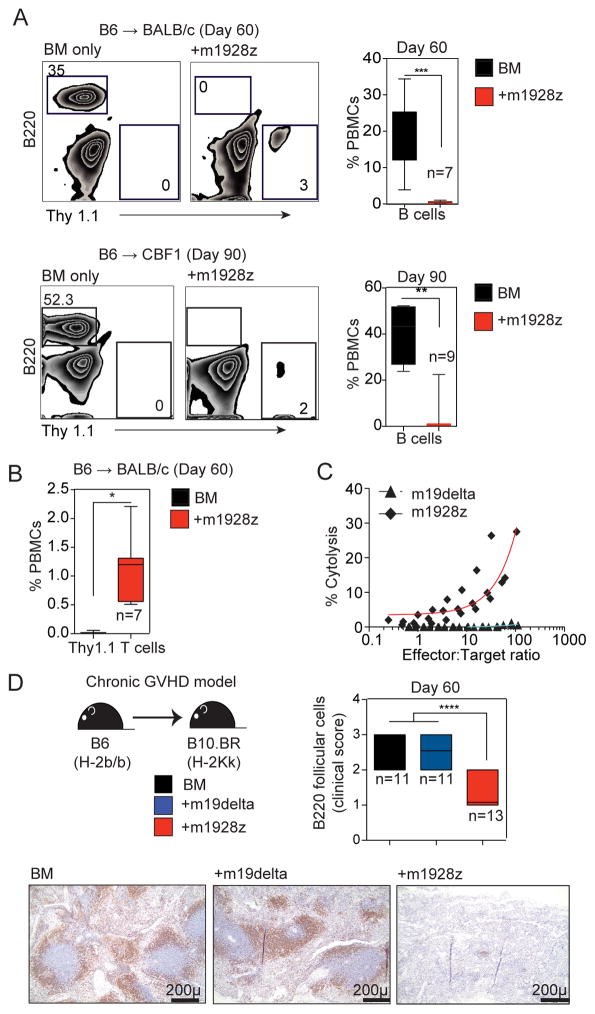

Despite decreased GVHD, the bulk m1928z T cell population maintained anti-CD19 activity in vivo as demonstrated by persistent B cell aplasia in allo-HSCT recipients of m1928z T cells (Figure 2A) and m1928z T cells were seen at least 60 days after HSCT (Figure 2B). Additionally, harvested m1928z T cells mediated ex vivo anti-CD19 lytic activity (Figure 2C). To study alloreactive CD19-CAR T cell activity over a more prolonged time-frame, we analyzed m1928z T cell activity against normal B cells in a chronic GVHD model (B6→B10.BR) that results in reduced intestinal pathology and attenuated lethality (Suppl Figure 5A) compared with acute GVHD models22. m1928z T cells again promoted reduced GVHD in this model, but mediated severe B cell aplasia compared with m19delta T cells that produced GVHD and concomitant mild alloreactivity-related B cell depletion in peripheral blood (Suppl Figure 5B). Histopathological analyses demonstrated loss of B cell follicles as well as loss of B220+ follicular B cells in recipients of m1928z T cells compared to m19delta T cells or BM only (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Allogeneic m1928z T cells mediate persistent B cell hypoplasia.

(A–C) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta and m1928z Thy1.1+B6 T cells. (A) Peripheral blood was drawn at day 60 or day 90 and CD45-gated events analyzed for B220+B cells by flow cytometry. (B) CD45+Thy1.1+T cells were detected in peripheral blood. (C) Splenocytes were harvested at day 14 and used as effectors, and labeled EL4-CD19 were used as targets in Cr-51 release in vitro cytotoxicity assay. The proportions of donor T cells in spleens were determined by flow cytometry and the effective effector-to-target ratios are depicted. A representative of two independent experiments with similar results is shown (n=4, with lysis set up in triplicates). (D) B10.BR recipients were conditioned with cyclophosphamide on days −3 and −2 and TBI (7.5 Gy) on day −1 and reconstituted with 10 × 106 lin-depleted BM cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta or m1928z T cells. The size of B220+ splenic follicles were scored after IHC staining. Pooled data from two independent experiments are depicted in the right panel and representative micrographs are shown in the lower panel. Black bar on micrographs indicate a field length of 200 microns. ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

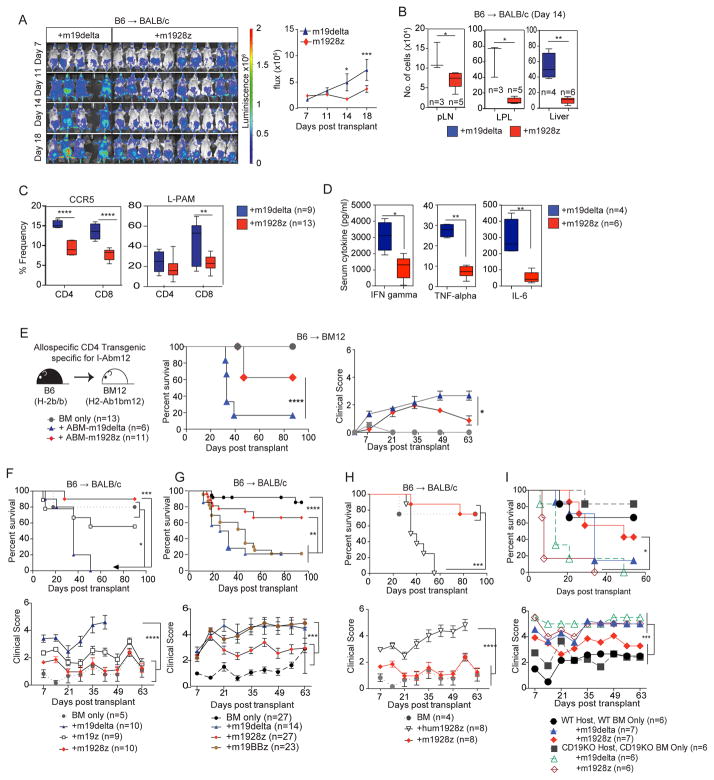

We hypothesized that the decreased GVHD potential of m1928z T cells resulted from cumulative CAR and alloreactive TCR signaling leading to exhaustion and eventual deletion of alloreactive CAR+ T cells, while non-alloreactive CAR+ T cells retained activity against CD19+ targets. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed the in vivo expansion and distribution of m1928z T cells by infusing luciferase-expressing B6 m1928z or m19delta T cells into B6→BALB/c recipients. Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) revealed significantly reduced expansion of m1928z T cells compared to m19delta T cells (Figure 3A). Additionally, there were fewer splenic donor CD8+ T cells in recipients of m1928z T cells vs. m19delta T cells at day-7 post-HSCT (Suppl Figure 6A). GVHD target organs and lymph nodes also revealed fewer Thy1.1+ donor m1928z T cells compared to m19delta T cells (Figure 3B). Splenocytes isolated at day-14 displayed reduced frequency of Thy1.1+ donor T cells expressing the gut homing markers CCR5 and LPAM in recipients of m1928z T cells vs. m19delta T cells (Figure 3C). Further T cell immunophenotypic analyses revealed significantly fewer activated and effector-memory CD8+ T cells in spleens of mice receiving m1928z vs. m19delta T cells 7 days post-transplant (Suppl Figure 6B). No differences in T cell polarization were identified in the expression of transcription factors for Th1 (T-bet), Th2 (GATA-3) or T-regulatory (Foxp3) cells in splenocytes (Suppl Figure 6C). We also found significantly lower levels of IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha and IL-6 in sera from B6→BALB/c recipients of m1928z vs. m19delta T cells at day-7 (Figure 3D). We investigated if a high burden of malignant CD19+ cells might enhance m1928z T cell cytokine production and activation, which could phenocopy cytokine release syndrome and exacerbate GVHD. In a modification of the B6→BALB/c model that included pre-transplant, established A20 lymphoma we identified lower serum levels of GM-CSF, IFN-gamma, IL-6, and TNF-alpha in recipients of m1928z vs. m19delta T cells (Suppl Figure 7). These data suggest that the reduced proliferation (Figure 3A) and ex vivo recovery (Figure 3B and Suppl Figure 6A) of m1928z T cells compared with m19delta T cells result in fewer functional T cells to elaborate cytokines in response to lymphoma cells in vivo. Importantly, our data are in disagreement with a model in which enhanced cytokine secretion by m1928z CAR T cells in response to lymphoma cells promotes GVHD or cytokine release-mediated lethality as was seen in the recent murine study23. Possible reasons for this difference include intrinsic structural differences in the CAR constructs which can influence the survival and activity of CAR T cells In response to antigen challenge24.

Figure 3. Allogeneic m1928z T cells exhibit decreased alloreactive proliferation and GVHD target organ infiltration.

(A) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with luciferase+Thy1.1+B6 1×106 m19delta, or m1928z T cells. Bioluminescence imaging of the transplanted mice was performed weekly and flux was measured. Animals from one representative experiment and flux pooled from two independent experiments are shown. (B–D) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta, or m1928z T cells. Data from two independent experiments are depicted. (B) Tissues were harvested at day 14, homogenized and counted, and single cell suspensions analyzed by flow cytometry. The calculated numbers of donor Thy1.1+T cells in pLN, LPL and liver are shown. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments. (C) Splenocytes were harvested and frequencies of CCR5 and L-PAM determined by flow cytometry. Data from two independent experiments are depicted. (D) Cytokine expression in the serum was assessed at day 7 with Luminex multiplex assay. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments. (E) Lethally irradiated BM12 recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 2×105 ABM m19delta or m1928z T cells and survival and GVHD were monitored. (F–H) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells and designated groups were treated with B6 1×106 m19delta, m1928z, m19z, m19BBz and hum1928z T cells. Survival and weekly clinical GVHD scores were monitored. Results are pooled from two independent experiments. (I) Lethally irradiated recipients (BALB/c or BALB/c CD19KO) were reconstituted with B6 or B6 CD19KO lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×106 B6 m19delta or m1928z T cells. Survival and weekly clinical GVHD scores were monitored. Results are depicted from one of two independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

To assess the contribution of the alloreactive TCR in decreased GVHD, we took advantage of a monoclonal TCR transgenic GVHD model in which donor ABM-TCR-transgenic RAG1 knockout (KO) donor T cells target the allelic MHC class II molecule I-Abm12 expressed by B6.C-H2bm12 (BM12) recipients. Transfer of ABM T cells is sufficient to cause GVHD in BM12 recipients, as well as BM12 allo-HSC graft rejection in immunodeficient mice25. We again observed significantly less GVHD in allo-HSCT BM12 recipients of ABM m1928z vs. m19delta T cells (Figure 3E). Combined with the results above demonstrating reduced proliferation and cytokine production by m1928z vs. m19delta T cells, this result further compounds a model where m1928z T cells develop functional exhaustion in allogeneic hosts.

To investigate the role of costimulatory signals in CAR-mediated protection from GVHD, we compared first generation m19z T cells lacking enforced costimulation with. CD28-costimulated m1928z T cells (Figure 1A) in the B6→BALB/c GVHD model (Figure 3F). m19z T cells produced significantly more GVHD mortality than m1928z T cells (even though less severe than m19delta T cells), suggesting that enforced costimulation affects the strength of protection from GVHD. As 4-1BB based CARs have been shown to attenuate development of exhaustion in response to repetitive CAR signaling26,27, we compared m19BBz T cells with m1928z T cells (Figure 1A and Figure 3G). Donor m19BBz B6 T cells mediated significantly more lethal GVHD than m1928z T cells, similar to m19delta T cells. Finally, we assessed if the autonomous signaling from the CD28z cytoplasmic domain in the absence of antigen triggering was sufficient to protect against GVHD by comparing GVHD in recipients of hum1928z (Figure 1A) vs. m1928z T cells. Donor hum1928z T cells mediated significantly more lethal GVHD vs. m1928z T cells indicating that antigen-triggered signaling through the m1928z CAR was required for suppression of GVHD (Figure 3H).

To demonstrate the requirement of m1928z signaling in protection from GVHD, we utilized Ighmtm1Cgn (mu-deficient) mice (which lack mature B cells) as bone marrow donors and RAG2KO BALB/c mice (which lack mature T and B cell population) as recipients (Suppl Figure 8). m1928z B6 T cells mediated significantly more GVHD mortality in RAG2KO BALB/c recipients of mu-deficient BM vs. RAG2KO BALB/c recipients of B6 wildtype BM, suggesting that reduction of B cell number in hosts prevented m1928z signaling-mediated protection from GVHD. We hypothesized that the mu-deficient reconstituted RAG2KO mice could still promote activation of m1928z signaling due to the presence of CD19+ pre-B cells in these mice28. We therefore used B6 CD19KO donors to reconstitute BALB/c CD19KO recipients, which lack the cognate antigen of the CD19-CAR29. CD19-deficient allo-HSCT recipients of CD19-deficient BM infused with B6 m1928z T cells demonstrated similar lethal GVHD as those infused with B6 m19delta T cells (Figure 3I). These data indicate that m1928z signaling in response to normal B cells is necessary for inhibition of GVH responses.

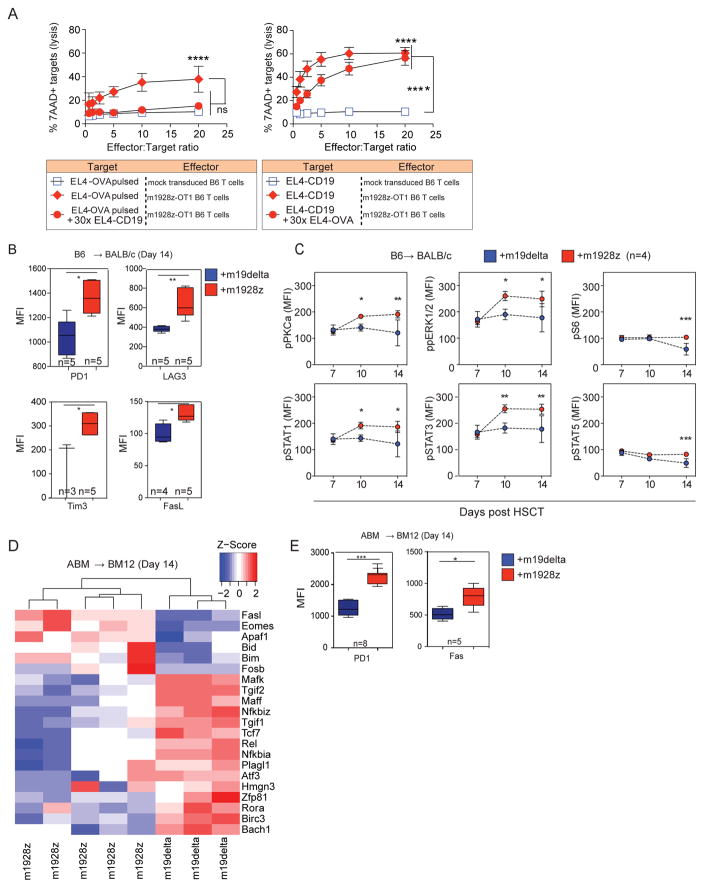

GVHD is mediated by alloreactive TCR activation, and CAR-expressing alloreactive T cells likely experience concurrent stimulation via both the CAR and the TCR in response to allogeneic B cells. To study the effect of CAR stimulation on TCR-directed killing, we generated a novel tri-cistronic vector, m1928z-OT-1, which promotes coordinated expression of m1928z and the OT-1 (OVA-specific) TCR (Suppl Figure 9). Polyclonal B6 m1928z-OT-1 T cells were tested as effectors against EL4 targets pulsed with OVA peptide (EL4-OVA) in the presence or absence of excess EL4-mCD19 targets. Unlabeled and unpulsed EL4-CD19 (CAR-directed distractor) cells were added at 30x-excess relative to CFSE-labeled EL4-OVA primary targets (TCR target). Presence of EL4-CD19 target cells resulted in a significant reduction in cytolysis of EL4-OVA targets mediated through the OT-1 TCR (Figure 4A left panel). TCR-stimulation by excess ova-pulsed targets also inhibited killing of targets mediated by CAR signaling (Figure 4A right panel). This demonstrates that both a CAR and TCR can remain functional when simultaneously expressed, and activation of a T cell through one receptor can impair lytic activity mediated by the other.

Figure 4. Alloreactive m1928z T cells are hyperactive, exhausted and undergo deletion.

(A) m1928z-OT-1 TCR T cells or untransduced T cells were used as effectors. Left panel: CFSE labeled EL4-cells pulsed with OVA peptide (10 μM SIINFEKL) were used as targets with or without non-labeled EL4-CD19 cells as distractor. Right panel: CFSE labeled EL4-CD19 cells were used as targets with or without non-labeled EL4 cells pulsed with OVA peptide (10 μM SIINFEKL) as a distractor. Lysis at 5 hours was estimated as the percentage of 7AAD+ CSFE+ targets divided by total CSFE+ targets. Combined data from three experiments are shown (n = 9 replicates/data point). Each data point reflects the average + SEM. Two-tailed paired t-tests were performed for selected comparisons as depicted. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. (B, C) Lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with Thy1.1+B6 1×106 m19-delta.GFP or m1928z.GFP T cells. (B) Splenocytes harvested at day 14 post-HSCT were counted and surface expression of exhaustion markers was measured on Thy1.1+GFP+ gated cells. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments. (C) Splenocytes harvested on designated days post-HSCT were harvested and phosphorylation status evaluated on Thy1.1+GFP+ gated cells. (D, E) Lethally irradiated BM12 recipients were reconstituted with B6 lin-depleted bone marrow cells. Designated groups were treated with 1×105 ABM m19delta.GFP or m1928z.GFP T cells. Splenocytes harvested at day 14 post-HSCT. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments. (D) Global transcriptional profiles of FACS sorted GFP+CAR T cells, (E) Splenocytes were counted and surface expression of exhaustion markers measured on GFP+CAR T gated cells. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments.

Chronic, repetitive activation of T cells via the endogenous TCR has been shown to result in anergy, exhaustion, and AICD in chronic viral infection and tumor/self-antigen pre-clinical models30. Mouse models of dual-TCR expressing T cells have demonstrated that T cells can be tolerized by chronic exposure to antigen leading to chronic exhaustion31,32. More recently, an exhaustion signature has been demonstrated in autonomously signaling GD2-CAR T cells signaling through CD28 but not 4-1BB costimulatory domains27. We studied the immunophenotypic markers of exhaustion in the m1928z T cells post-transplant and found a significantly higher expression of PD-1, LAG3 and Tim3 in splenic m1928z T cells of allo-HSCT recipients on day 14 (Figure 4B). While our findings suggest an exhaustion phenotype, these markers are also expressed in response to strong and chronic T cell activation. We therefore assessed the signal transduction pathways of B6 m1928z T cells obtained from BALB/c transplant recipients on days 7, 10 and 14 post-HSCT, by analyzing TCR signaling using Phosflow analysis (Figure 4C). We noted significantly higher levels of phosphorylated PKCa, pERK1/2, pS6, pSTAT1, pSTAT3, and pSTAT5 in donor m1928z T cells compared to m19delta T cells. These results suggest enhanced T cell stimulation in m1928z T cells as a consequence of stimulation via both the CAR and the alloreactive TCR.

We next performed experiments to determine if this enhanced T cell signal transduction produces a gene expression profile consistent with exhaustion or AICD. We adoptively transferred ABM T cells transduced with either the m19delta.GFP or m1928z.GFP (Figure 1A) into BM12 recipients of B6 BM and performed transcriptome profiling on day-14-sorted splenic GFP+ CAR T cells from allo-HSCT recipients, an approach that ensured that only cells capable of receiving signals through both the TCR and CAR were included in the analysis (Figure 4D). Microarray data were consistent with a population of T cells undergoing exhaustion and deletion as evidenced by upregulation of Bim, Bid, FasL, Apaf1 and Eomes, as well as down-regulation of Tcf7, which is associated with progressive T cell differentiation and loss of self-renewal function33,34. Pathway analysis showed that the greatest differences between m1928z vs. m19delta T cells were in apoptosis pathways, especially pathways related to programmed cell death, caspase activation, and FasL signaling. We validated the array data by flow cytometry of GFP+ CAR T cells, confirming increased surface expression of Fas, along with the previously observed increase in PD-1 expression (Figure 4E). These data suggest that alloreactive m1928z cells receive increased cumulative T cell signaling in response to CD19 and allo-antigens leading to chronic activation and eventual functional exhaustion and programmed cell death.

Recent clinical studies have reported minimal incidence of GVHD in recipients of donor CD19-CAR T cells for treatment of B cell malignancies, which had progressed after allo-HSCT17,16. The donor 1928z T cells were infused in the post-transplant setting without lymphodepletion prior to T cell infusion. Consistent with our data, one study also reported increased expression of PD-1 on donor-derived allogeneic CAR T cells16. Our data demonstrate that alloreactive CAR T cells undergo hyperactivation, exhaustion, and subsequent deletion mediated by CD28 costimulation and CD3-zeta signaling in multiple GVHD models characterized by different MHC disparities and alloreactive T cells. We also show that concurrent activation of the CD19-specific CAR and TCR can promote acute lytic exhaustion of dual-specific T cells. Together, these results suggest that both acute and chronic stimulation of T cells via the m1928z can negatively affect the responsiveness of T cells to antigen presented to the TCR, independent of the TCR specificity.

These findings may explain results showing impaired activity of virus-specific CD19-CAR T cells, which would be expected to receive dual stimulation through their CAR and TCR in vivo35. Phase 1 data suggest that while donor-derived CD19-CAR-modified virus-specific T cells maintained activity against CD19+ targets when administered in the post-transplant setting to patients with relapsed B cell malignancies, there was a suggestion of an inverse correlation between T cell persistence and CD19+ cell counts (both ALL/CLL and normal B cells)7. In this setting, T cell survival could be negatively affected by recurrent CAR activation by CD19 and allo-antigens that were not eliminated by pre-infusion chemotherapeutic lymphodepletion.

We show that the presence of CD19 antigen, either in mature B cells or tumor cells, is critical to protection from GVHD. When intended for management of minimal residual disease (MRD), adoptive transfer of 1928z T cells should thus be performed after a timeframe of B cell recovery, which is transplant dependent36.

In summary, our data provide mechanistic insight into recent clinical trial results demonstrating that allogeneic donor CD19-specific CD28z CAR T cells promote anti-lymphoma activity, with minimal GVHD. Our results support a model in which alloreactive T cells expressing CD19-specific CD28z CARs undergo progressive activation in response to dual TCR and CAR signaling, resulting in loss of function and possible deletion. These findings caution about the complexity of relying on multiple antigen receptors in clonal T cells. Our findings further demonstrate a requirement for the presence of CD19+ targets to mediate the inhibition of the GHVD potential of m1928z T cells and indicate that infusion of donor 1928z T cells in the post-transplant setting will produce the lowest incidence of GVHD when infused after B cell recovery.

Online Materials and Methodology

Mouse HSCT, GVHD and GVL models

We obtained C57BL/6 (B6), C57BL/7.Thy1.1 (Thy1.1+B6), CBF1, B10.BR, BALB/c and BM12 mice from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). ABM transgenic mice1 were provided by M. Sayegh (Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA) and had been backcrossed onto a B6 background for at least 20 generations These mice were then crossed on a RAG1KO background derived from the Jackson Laboratory, which had been previously backcrossed to B6 background for ten generations. Mice used for experiments were 6–9 weeks old. They were co-housed in three to five mice/cage in all experiments. Mouse HSCT experiments with a MHC disparate model (B6 → BALB/c) and a haploidentical model (B6 → CBF1) have been used extensively by others as well as by us2,3. The chronic GVHD model (B6 → B10.BR) has been described in detail previously4. The T cells were generated from splenocytes, as outlined, and injected via tail vein at the time of the allograft injection. The recipients were monitored daily for survival and scored weekly on a 10-point scale in a blinded fashion for signs of clinical GVHD as described previously5. Animals with scores greater than five were euthanized. Blinded histopathological assessment of GVHD in liver, small intestine, and large intestine was performed at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts, USA), and University of Florida (Gainesville, Florida, USA) as previously described2.

In A20 lymphoma experiments, animals received 0.5×106/mouse tumor cells on day 0 in a separate injection or 10×106/mouse on day −7 intravenously, where indicated. All studies were approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under protocol 99-07-025.

CAR constructs and CAR T cell production

The CAR constructs and T cell production have been described previously6. The constructs include a single-chain fragment variable (scFv), composed of a mouse CD8 signal peptide, IgH rearrangement, glycine-serine linker, and IgL rearrangement. The scFv was fused to the mouse CD8 hinge and transmembrane region and mouse stimulatory domains including mouse CD28 and/or mouse CD3ζ. The CAR construct was cloned into the vector backbone SFG, which is a Moloney murine leukemia-based retroviral vector.7 The m1928z-OT-1 TCR tricistronic retroviral construct was generated using standard cloning techniques. pENTR1A no ccDB (w48-1) was a gift from Eric Campeau (Addgene plasmid # 17398). Murine TCR OTI-2A.pMIG II was a gift from Dario Vignali (Addgene plasmid # 52111). The m1928z construct was cloned into pENTR1A in frame followed by the E2A self-cleaving peptide. The OT-I TCR alpha and beta chains were separated by the T2A self cleaving peptide. The tricistronic construct was recombined into the LZRS-Rfa vector using Gateway LR Clonase II Enzyme mix (Invitrogen). LZRS-Rfa was a gift from Paul Khavari (Addgene plasmid # 31601). For retrovirus production, Phoenix-E packaging cells were transfected with the retroviral vectors using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) and viral supernatant used for transduction. For CAR T cell generation, splenic T cells were activated with CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Invitrogen) and IL-2 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Spinoculations were done twice with the viral supernatant.8

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

A20-TGL and T cells from luciferase-expressing mice (a gift from Robert Negrin, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA) were visualized using in vivo bioluminescence imaging systems (Caliper Life Sciences)2. The bioluminescent flux was analyzed using Living Image software, version 4.3 (Caliper Life Sciences).

In vitro cytolysis

In vitro cytolysis of targets were determined by measuring chromium-51 (51Cr) release from labeled target cells as described previously3. For cold target inhibition assay polyclonal B6 m1928z-OT-1 TCR T cells were added at varying effector:target ratios to targets with or without secondary “cold” targets. Primary targets – EL4-CD19 or EL4 pulsed with 10 μM SIINFEKL (OVA) peptide (Invivogen) – were labeled with 0.5 μM CSFE (Molecular Probes) and added to 96-well plates at 104 targets/well. In cold target wells, a 30× excess of non-CFSE labeled secondary target was added. Target lysis was assessed by flow cytometry at 5 hours as the percentage of 7AAD+ targets (Molecular Probes).

Flow cytometry

Antibody staining of cultured T cells or tissues obtained from sacrificed mice was performed at 4°C with mouse Fc-block (Ebioscience) in 1% FBS in PBS. Stained cells were washed once with 1% FBS in PBS before being processed through a 5-laser BD LSRII (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry of blood cells was performed with a lyse-no wash preparation. Briefly, 25 μL of retro-orbital or cheek blood was incubated with antibodies for 25 minutes at 4°C. Afterwards, FACs Lysing Solution was added (BD Biosciences) and the cells were evaluated. All flow cytometry data files were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Protein L, an immunoglobulin-binding protein that binds to variable light chains of immunoglobulin without interfering with the antigen-binding site, was used to detect expression of the CAR9. To detect m1928z-OT1 TCR, T cells were stained with CD19-His (Sinobiological) followed by anti-His-PE staining (Miltenyi) to demonstrate CD19-CAR expression, and then stained with anti-Vα2-APC (clone B20.1, Pharmingen) and anti-Vβ5.1/5/2-FITC (clone MR9-4, Pharmingen) to detect OT-1 TCR chains.

For Phosflow cytometry, transplanted mice receiving m19delta or m1928z CAR T-cells were harvested at day 7, 10 and 14 post-transplantation. Immediately after euthanasia, spleens were harvested and homogenized over a 70 uM cell-strainer. Cells were rinsed through the strainer with pre-warmed RPMI-1640 containing 2% paraformaldehde (PFA). After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 - 2% PFA and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Subsequently cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in ice-cold methanol and kept at −20°C for 1 hour. After washing with PBS, permeabilized cells were finally stained with CD90.1 and the following phospho-specific antibodies: pPKCa-pT497, ppERK1/2-pT202/pY204, pS6-pS235/pS236, pSTAT1-pS727, pSTAT3-pY705, pSTAT5-pY694 (BD). CAR T-cell phosphorylation status was evaluated in CD90.1/GFP double positive cells.

Microarray

Spleens were harvested on day 14 and FACS-sorted on GFP-expressing CAR T cells. The sorted T cells were placed in Trizol and RNA was isolated. Microarray was performed with Affymetrix MOE 430A 2.0. Microarray data was processed using the standard R/Bioconductor packages: gcRMA (based on Robust Multi-Array Average method) for quantitation and normalization and LIMMA empirical Bayes method for differential expression10,11. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the R hclust function with the Euclidean distance measure. A heatmap was generated using the heatmap.2 function from the gplots R package. All generated microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession code GSE85397 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=qnehygkqljmtjop&acc=GSE85397).

Cytokine Detection

Retro-orbital blood was collected from mice and serum prepared by centrifugation after clotting of blood. Serum was incubated with a Milliplex multi-analyte panel for mouse cytokines (EMD Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts) and analyzed on a Luminex 100 system.

Statistics

Survival curves were analyzed with a Mantel-Cox (Log rank) test, and grouped comparisons were made using a Mann-Whitney U test or 2-way ANOVA. Calculations were performed using Excel (Microsoft) and Prism software (GraphPad Software). Data represent the means ± SEM. In box whisker diagrams, median is shown with a horizontal line, the box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles and the whiskers extend from the smallest value and up to the largest. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figures

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health award numbers R01-HL069929 (M.R.M. van den Brink), R01-AI101406 (M.R.M. van den Brink), P01-CA023766 (M.R.M. van den Brink) and R01–AI100288 (M.R.M. van den Brink). The Lymphoma Foundation, The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, MSKCC Cycle for Survival, and P30 CA008748 MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant. A. Ghosh is a fellow of the Lymphoma Research Foundation. M. Smith received funding from a NIH Diversity Supplement (PA-16-288) under R01 AI100288-08S1, the M. J. Lacher Research Fellowship (The Lymphoma Foundation), and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation New Investigator Award. M. Smith and S. James are supported under an NIH T32 grant (T32-CA009207). S. James is also a Young Investigator Awardee from the Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO. M.L. Davila is supported by an ASH-AMFDP career development award, Damon Runyon Fund and K08 CA148821 (NCI). J.L. Zakrzewski is supported by LLS TRP grant 6465-15 and K08 CA160659 (NCI). A.Z. Tuckett is supported by a grant from the Imaging and Radiation Sciences (IMRAS) Program of MSKCC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. We are thankful to R. Negrin, Stanford for the A20-TGL cell line, E Campeau, UMASS for pENTR1A, D Vignali, UPMC for murine TCR OTI-2A.pMIG II and P. Khavari, Stanford for LZRS-Rfa plasmid. We appreciate the help of J. White, LCP, RARC, flow cytometry core facility, integrative genomics core and computational biology core, MSKCC. We also appreciate the help of H. Poeck for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

AG and MLD conceived the project. AG, MeS, SEJ and MLD contributed to the design of the experiments, supervised and conducted the experiments, generated the manuscript figures and wrote the manuscript. EV and KVA conducted the experiments and generated the manuscript figures. FP contributed to the conduct and interpretation of microarray analyses. ACFM, GFM and CL contributed to the conduct and interpretation of histological analyses. GG, FMK, ERL, SL, HJ, AZT, LT, LFY and KT assisted in conducting experiments. JLZ, JAD, RRJ, AMH and AS contributed to the design of the experiments and their analyses. MiS and MRMvdB supervised the project, contributed to the design of the experiments and their analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interest

M. Sadelain is a scientific cofounder of Juno Therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ho WY, Blattman JN, Dossett ML, Yee C, Greenberg PD. Adoptive immunotherapy: engineering T cell responses as biologic weapons for tumor mass destruction. Cancer cell. 2003;3:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadelain M, Riviere I, Brentjens R. Targeting tumours with genetically enhanced T lymphocytes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:35–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill S, June CH. Going viral: chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for hematological malignancies. Immunological reviews. 2015;263:68–89. doi: 10.1111/imr.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Riviere I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer discovery. 2013;3:388–398. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James SE, et al. Antibody-mediated B-cell depletion before adoptive immunotherapy with T cells expressing CD20-specific chimeric T-cell receptors facilitates eradication of leukemia in immunocompetent mice. Blood. 2009;114:5454–5463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-232967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brentjens RJ, et al. Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes co-stimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat Med. 2003;9:279–286. doi: 10.1038/nm827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadelain M. CAR therapy: the CD19 paradigm. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3392–3400. doi: 10.1172/JCI80010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kochenderfer JN, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:540–549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalos M, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brentjens RJ, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2011;118:4817–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brentjens RJ, et al. CD19-Targeted T Cells Rapidly Induce Molecular Remissions in Adults with Chemotherapy-Refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5:177ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grupp SA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davila ML, et al. Efficacy and Toxicity Management of 19–28z CAR T Cell Therapy in B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra225. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DW, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maude SL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brudno JN, et al. Allogeneic T Cells That Express an Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Induce Remissions of B-Cell Malignancies That Progress After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation Without Causing Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1112–1121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochenderfer JN, et al. Donor-derived CD19-targeted T cells cause regression of malignancy persisting after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;122:4129–4139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davila ML, Kloss CC, Gunset G, Sadelain M. CD19 CAR-targeted T cells induce long-term remission and B Cell Aplasia in an immunocompetent mouse model of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PloS one. 2013;8:e61338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh A, et al. PLZF Confers Effector Functions to Donor T Cells That Preserve Graft-versus-Tumor Effects while Attenuating GVHD. Cancer research. 2013;73:4687–4696. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh A, et al. Adoptively transferred TRAIL+ T cells suppress GVHD and augment antitumor activity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2654–2662. doi: 10.1172/JCI66301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bar M, et al. Donor lymphocyte infusion for relapsed hematological malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: prognostic relevance of the initial CD3+ T cell dose. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19:949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivasan M, et al. Donor B-cell alloantibody deposition and germinal center formation are required for the development of murine chronic GVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood. 2012;119:1570–1580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacoby E, et al. Murine allogeneic CD19 CAR T cells harbor potent antileukemic activity but have the potential to mediate lethal GVHD. Blood. 2016;127:1361–1370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-664250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochenderfer JN, Yu Z, Frasheri D, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive transfer of syngeneic T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor that recognizes murine CD19 can eradicate lymphoma and normal B cells. Blood. 2010;116:3875–3886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenq RR, et al. Regulation of intestinal inflammation by microbiota following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:903–911. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Z, et al. Structural Design of Engineered Costimulation Determines Tumor Rejection Kinetics and Persistence of CAR T Cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long AH, et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nature medicine. 2015;21:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nm.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan M, Polic B, Bralic M, Jonjic S, Rajewsky K. Incomplete block of B cell development and immunoglobulin production in mice carrying the muMT mutation on the BALB/c background. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3463–3471. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3463::AID-IMMU3463>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1317–1318. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teague RM, et al. Peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance to self-proteins is regulated proximally at the T cell receptor. Immunity. 2008;28:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schietinger A, Delrow JJ, Basom RS, Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. Rescued tolerant CD8 T cells are preprogrammed to reestablish the tolerant state. Science. 2012;335:723–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1214277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paley MA, et al. Progenitor and terminal subsets of CD8+ T cells cooperate to contain chronic viral infection. Science. 2012;338:1220–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1229620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gattinoni L, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz CR, et al. Infusion of donor-derived CD19-redirected virus-specific T cells for B-cell malignancies relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant: a phase 1 study. Blood. 2013;122:2965–2973. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Small TN, Robinson WH, Miklos DB. B cells and transplantation: an educational resource. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Sayegh MH, et al. Allograft rejection in a new allospecific CD4+ TCR transgenic mouse. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:381–389. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh A, et al. PLZF Confers Effector Functions to Donor T Cells That Preserve Graft-versus-Tumor Effects while Attenuating GVHD. Cancer research. 2013;73:4687–4696. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh A, et al. Adoptively transferred TRAIL+ T cells suppress GVHD and augment antitumor activity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2654–2662. doi: 10.1172/JCI66301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan M, et al. Donor B-cell alloantibody deposition and germinal center formation are required for the development of murine chronic GVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood. 2012;119:1570–1580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmaltz C, et al. T cells require TRAIL for optimal graft-versus-tumor activity. Nat Med. 2002;8:1433–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila ML, Kloss CC, Gunset G, Sadelain M. CD19 CAR-targeted T cells induce long-term remission and B Cell Aplasia in an immunocompetent mouse model of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PloS one. 2013;8:e61338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riviere I, Brose K, Mulligan RC. Effects of retroviral vector design on expression of human adenosine deaminase in murine bone marrow transplant recipients engrafted with genetically modified cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:6733–6737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Sadelain M, Brentjens R. Retroviral transduction of murine primary T lymphocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;506:83–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-409-4_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Z, Chinnasamy N, Morgan RA. Protein L: a novel reagent for the detection of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) expression by flow cytometry. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figures