Trends and Predictors of Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation Following Acute Myocardial Infarction: Data From the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Participation in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) after acute myocardial infarction has been proven to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality. Historically, participation rates have been low, and although recent efforts have increased referral rates, current data on CR participation are limited.

Methods and Results

Utilizing data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System conducted by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we performed a population‐based, cross‐sectional analysis of CR post‐acute myocardial infarction. Unadjusted participation from 2005 to 2015 was evaluated by univariable logistic regression. Multivariable logistic regression was performed with patient characteristic variables to determine adjusted trends and associations with participation in CR in more recent years from 2011 to 2015. Among the 32 792 survey respondents between 2005 and 2015, participation ranged from 35% in 2005 to 39% in 2009 (_P_=0.005) and from 38% in 2011 to 32% in 2015 (_P_=0.066). Between 2011 and 2015, participants were less likely to be female (odds ratio [OR] 0.763, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.646‐0.903), black (OR 0.700, 95% CI 0.526‐0.931), uninsured (OR 0.528, 95% CI 0.372‐0.751), less educated (OR 0.471, 95% CI 0.367‐0.605), current smokers (OR 0.758, 95% CI 0.576‐0.999), and were more likely to be retired or self‐employed (OR 1.393, 95% CI 1.124‐1.726).

Conclusions

Only one third of patients participate in CR following acute myocardial infarction despite the known health benefits. Participants are less likely to be female, black, and uneducated. Future studies should focus on methods to maximize the proportion of CR referrals converted into CR participation.

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, morbidity, mortality, myocardial infarction

Subject Categories: Exercise, Lifestyle, Secondary Prevention

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

- Only one third of patients participate in cardiac rehabilitation following acute myocardial infarction despite its known health benefits.

- Participation levels in cardiac rehabilitation have remained relatively flat over the past decade despite increases in referral rates.

- Women, blacks, and uneducated patients are less likely to participate in cardiac rehabilitation.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

- Encouraging cardiac rehabilitation participation is important for all patients following acute myocardial infarction, particularly in vulnerable populations.

- Because higher referral rates to cardiac rehabilitation do not necessarily translate into increased participation, other measures such as optimizing insurance coverage and improving access may help to increase participation.

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) incorporates graduated cardiovascular exercise, risk factor modification, education, and social support services.1 Participation in CR after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a safe and effective intervention that is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality.2, 3, 4, 5 Specifically, participation in CR has been correlated with lower unplanned readmissions, higher quality‐of‐life metrics, healthy lifestyle behavioral choices, and improved exercise capacity.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Despite these proven benefits, CR is not routinely prescribed following AMI. Moreover, even when prescribed, rates of patient participation in CR have been historically low due to limited access, lack of insurance coverage, and out‐of‐pocket cost for co‐pays.8, 9, 10 Although data from the 1990s and early 2000s have demonstrated the effect of demographic and socioeconomic factors on CR referral and participation,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 current data are lacking. The goal of this study was to assess the current trends in CR participation after AMI in the United States and to identify predictors of participation.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for the purpose of reproducing the results because these data are already available in the public domain on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.16

Study Population

We performed a population‐based, cross‐sectional study, using data from the BRFSS (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) conducted by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.16 We acknowledge that the Centers for Disease Control's BRFSS is the original source of the data. Institutional review board approval was not obtained because this is a public use data set, and the data available are not individually identifiable. Data from BRFSS surveys obtained between 2005 and 2015 were collected, and survey‐weighted CR participations post‐AMI were calculated. The survey question was phrased as 1 of the following: After you left the hospital following your heart attack did you go to any kind of outpatient rehabilitation? (2005) After you left the hospital following your heart attack did you go to any kind of outpatient rehabilitation? This is sometimes called “rehab.” (2007) Following your heart attack, did you go to any kind of outpatient rehabilitation? This is sometimes called “rehab.” (2009‐2015) The survey question was not limited to the year in which the survey was conducted; therefore, it represents lifetime participation in CR post‐AMI (ie, survey year 2005 represented CR participation in all years up to and including 2005). Patients responding “Don't Know/Not Sure” or who declined to answer the survey question regarding CR were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

To assess for unadjusted trends in participation, univariable logistic regression was performed with CR as the outcome and survey years (2005‐2015) as the categorical predictor. The BRFSS survey methodology changed between 2009 and 2011 by allowing addition of data collection by cellular telephones; therefore, analyses were performed using the 2005‐2009 and the 2011‐2015 data sets separately. Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients who did and did not participate in CR were compared by survey‐weighted Rao‐Scott chi‐squared tests. Comorbidities were determined by BRFSS survey questions in which participants responded if they had ever been told by a health professional that they had a certain condition (eg, “high cholesterol,” “high blood pressure”). Current smokers were defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in the participant's life and currently smoking cigarettes “every day” or “some days.” Former smokers were defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in the participant's life and currently not smoking cigarettes.

To assess for adjusted trends and associations with participation in CR in more recent years (2011‐2015), multivariable logistic regression was performed with CR as the outcome and patient characteristic variables and survey year as predictor variables. Variables were selected based on findings from prior studies and physiologic rationale for potential association with CR nonparticipation. These independent variables included sex, race, insurance status, employment status, education level, marital status, smoking status, region, and survey year. For the survey years included, regions included the following states: Northeast (Connecticut), Southeast (Arkansas, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Puerto Rico), Midwest (Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin), and West (Arizona, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, Washington). Age was not included in the multivariable regression because a participant's age at the time of the survey did not necessarily correlate with his or her age at the time of the AMI and the CR participation decision. In order to investigate the possible influence of age despite this limitation, a separate univariable analysis was performed with the following groups: ages 18 to 64 and ages 65 years and older. Comorbidities were also excluded from the multivariable analysis due to missing data (ie, unanswered survey questions). Several categories sum to less than the total sample size responding to the CR survey question (11 773); this reflects that some participants were not asked, did not respond, or responded “Don't Know” to these questions, which represents less than 1% for every category except for race (3%), employment (21%), hypertension (25%), hyperlipidemia (5%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (22%). Analyses were performed with Statistical Analysis System software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at a _P_‐value of <0.05.

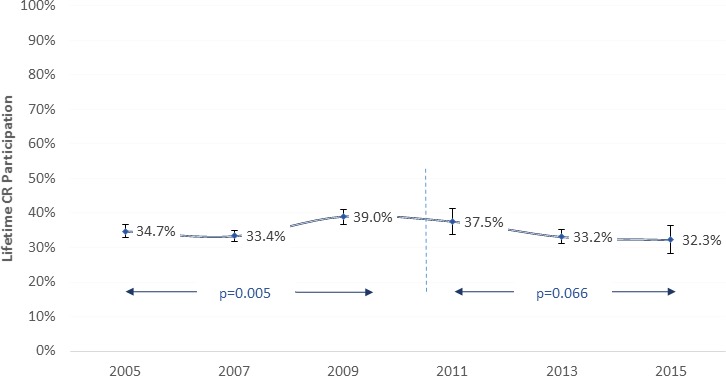

Results

From 2005 to 2015, 32 792 patients responded to the BRFSS survey question regarding CR. Of note, fewer than 1% of patients responded “Don't Know/Not Sure” each year except in 2005 (1.02%) and 2013 (1.58%). Additionally, fewer than 1% of patients declined the question regarding cardiac rehabilitation each year except from 2009 (1.08%) and 2013 (2.2%). Trends in participation in CR ranged from 32% to 39% (Figure, Table 1). There was a significant increase in participation from 2005 to 2009 (_P_=0.005) and a nonsignificant decrease between 2011 and 2015 (_P_=0.066). Baseline demographics of those who did and did not participate in CR from 2011 to 2015 are shown in Table 2. Patients who did not participate in CR were more likely to be younger, female, black/Hispanic/multiracial, unmarried, uninsured, unemployed or employed for wages (compared with self‐employed/student/retired), and to have less education. Nonparticipants were also significantly more likely to be current smokers and were less likely to have diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia. In the multivariable model, patients who participated in CR remained significantly less likely to be female, black, uninsured, current smokers, have less education, and were less likely to be employed for wages (or unemployed) compared with self‐employed/student/retired participants (Table 3). There was also significant regional variation with respondents from the Southeast and West regions being significantly less likely to participate in CR compared with those from the Midwest and Northeast (Tables 2 and 3). Additionally, patients aged 65 years and over were more likely to participate in CR compared with patients aged 18 to 54 (OR 1.787, 95% confidence interval 1.540‐2.074, P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Trends in lifetime cardiac rehabilitation participation following acute myocardial infarction from 2005 to 2015.

Table 1.

Trends in Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation—2005‐2015

| Survey Year | Survey Respondents | Lifetime CR Participants | Lifetime CR Participation | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 6650 | 2308 | 34.7% | 32.8 to 36.7 | Ref |

| 2007 | 9324 | 3114 | 33.4% | 31.8 to 35.0 | 0.283 |

| 2009 | 5045 | 1968 | 39.0% | 36.8 to 41.1 | 0.005 |

| 2011 | 2481 | 930 | 37.5% | 33.8 to 41.2 | Ref |

| 2013 | 8297 | 2755 | 33.2% | 31.2 to 35.2 | 0.041 |

| 2015 | 995 | 321 | 32.3% | 28.2 to 36.4 | 0.066 |

Table 2.

Participant Demographics and Comorbidities—2011‐2015

| Cardiac Rehabilitation | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=4237) | No (n=7536) | ||

| Age, y | |||

| 18 to 44 | 69 (4%) | 312 (10%) | <0.0001 |

| 45 to 64 | 1145 (34%) | 2484 (42%) | |

| 65+ | 3023 (62%) | 4740 (48%) | |

| Sex—female | 2587 (32%) | 3681 (40%) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 3511 (81%) | 5656 (70%) | <0.0001 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 276 (7%) | 764 (12%) | |

| Hispanic | 174 (8%) | 417 (12%) | |

| Othera | 196 (4%) | 532 (6%) | |

| Marital status—married | 2200 (59%) | 3198 (50%) | <0.0001 |

| Education | |||

| College graduate | 1164 (20%) | 1398 (12%) | <0.0001 |

| High school graduateb | 2584 (63%) | 4649 (60%) | |

| Less than high school graduate | 480 (17%) | 1469 (29%) | |

| Employment | |||

| Employed for wages | 436 (15%) | 742 (17%) | <0.0001 |

| Self‐employed/retiredc | 2289 (65%) | 3621 (50%) | |

| Unemployedd | 560 (20%) | 1607 (33%) | |

| Insurance status—insured | 4081 (95%) | 6910 (88%) | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker | 581 (16%) | 1646 (25%) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 3226 (99%) | 5629 (99%) | 0.356 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3035 (74%) | 4950 (68%) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1510 (37%) | 2470 (32%) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 1502 (36%) | 2562 (37%) | 0.718 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 473 (11%) | 738 (11%) | 0.780 |

| COPDe | 734 (23%) | 1537 (25%) | 0.128 |

| Depression | 1132 (27%) | 2117 (29%) | 0.313 |

| Region | <0.0001 | ||

| Northeast | 125 (3%) | 148 (2%) | |

| Southeast | 1803 (45%) | 4184 (56%) | |

| Midwest | 1225 (33%) | 1169 (19%) | |

| West | 1084 (20%) | 2035 (23%) |

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model for CR Participation—2011‐2015

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (ref: male) | 0.763 (0.646‐0.903) | 0.002 |

| Insurance status (ref: insured) | 0.528 (0.372‐0.751) | 0.0004 |

| Education (ref: college graduate) | ||

| High school graduatea | 0.688 (0.585‐0.810) | <0.0001 |

| Less than high school graduate | 0.471 (0.367‐0.605) | <0.0001 |

| Marital status (ref: married) | 0.862 (0.730‐1.018) | 0.080 |

| Employment (ref: wage employed) | ||

| Self‐employed/retiredb | 1.393 (1.124‐1.726) | 0.003 |

| Unemployedc | 1.041 (0.799‐1.355) | 0.767 |

| Smoking (ref: never smoker) | ||

| Former smoker | 1.148 (0.974‐1.353) | 0.100 |

| Current smoker | 0.758 (0.576‐0.999) | 0.049 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: white) | ||

| Black | 0.700 (0.526‐0.931) | 0.014 |

| Hispanic | 0.798 (0.498‐1.279) | 0.349 |

| Other | 0.710 (0.475‐1.062) | 0.095 |

| Region (ref: Midwest) | ||

| Southeast | 0.497 (0.416‐0.594) | <0.0001 |

| Northeast | 0.912 (0.602‐1.383) | 0.665 |

| West | 0.468 (0.379‐0.578) | <0.0001 |

| Survey year (ref: 2011) | ||

| 2013 | 0.993 (0.812‐1.215) | 0.949 |

| 2015 | 1.016 (0.764‐1.353) | 0.911 |

Discussion

Because higher referral rates to CR may translate into higher participation rates,17, 18 efforts to increase utilization of post‐AMI CR have focused primarily on improving physician referral rates. Data from the American Heart Association's Get With The Guidelines program demonstrated a nationwide average referral rate of 56% following admission for AMI, percutaneous coronary revascularization, and surgical revascularization between 2000 and 2007.19 More recently, an analysis from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry showed an increase in the rates of referral for post‐AMI CR from 72.9% of eligible patients in 2007 to 80.7% in 2012.20 The underlying problem, however, is that only one third to one half of patients referred to CR actually participate, and there is no evidence that this proportion has improved over the past several decades.10, 14 In fact, 1 study, albeit geographically limited (Mayo Clinic in Olmsted County, MN), reported no temporal increase in CR participation rates over a period of 23 years (from 1987 to 2010).4

Using the BRFSS data, we found that only one third of patients participated in CR following AMI over the past decade and that participation levels remained relatively flat over this time period despite increases in referral rates. Of note, the slight variation in CR participation demonstrated by the 2005‐2009 and 2011‐2015 data sets is driven, at least in part, by variations in states sampled throughout the survey years (the BRFSS weighting formula aims to adjust for these factors). For example, the 2013 survey included 6 of the top 10 lowest‐performing states (Hawaii, District of Columbia, Arkansas, Mississippi, Georgia, Tennessee) as compared with the 2009 survey, which included only 4 of these low‐performing states. While one‐third participation is higher than participation in the late 1990s,8, 9, 10 it is still strikingly low considering its proven beneficial effects in this patient population. Patient participation in CR is a focus of the Million Hearts Cardiac Rehabilitation Collaborative, supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services, which has set the goal of CR participation to 70% by 2022.21 Our results and the Mayo Clinic's data4 regarding CR participation should be interpreted in the setting of increasing CR referral rates over the past decade20 in that higher referral rates do not necessarily translate into increased participation. Several studies have shown that a more in‐depth discussion (either through telephone calls, home visits, or letters) and encouragement of enrollment by medical personnel result in higher CR participation rates.22, 23, 24, 25

Our study represents 1 of the largest analyses to date focused on CR participation following AMI. Prior studies have often been limited to data from single or several hospitals or a focus on the Medicare population.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Similar to these studies, we found a strong association between CR nonparticipation and female sex, nonwhite race, lack of insurance, tobacco use, and lower education levels. We also found that those who were self‐employed, homemakers, or retired were more likely to participate in CR, presumably because of schedule flexibility. In addition to health insurance coverage and ability to attend CR, insufficient access to CR programs remains an important limiting factor as demonstrated by studies that have found geographical proximity to appropriate CR facilities to be 1 of the strongest predictors of CR participation following AMI and coronary artery bypass surgery.11, 26 To overcome these barriers, some experts have suggested the development of home‐based CR programs27 or financial incentives for patients who participate.28

Our study has several limitations. First, it carries the inherent limitations of a cross‐sectional study—namely, the limited ability to clearly establish temporality of associations and the inability to define associations of causality. Second, these data consist of self‐reported CR participation, and although a correlation with actual participation is logical, this has not been rigorously established in the literature. Additionally, these data represent trends in lifetime CR participation, not annual participation rates. Given these characteristics, annual increases or decreases in the rate of CR participation may be partially blunted by the proportion of participants reporting CR from years before the survey. This concern is mitigated by the inclusion of data over a full decade; with such longitudinal data, even a subtle steady increase in participation would likely have been identifiable, if present. Further, the trend actually appears to reflect lower participation in recent years. Another limitation is that it is possible that some of the “predictors” of CR participation may have arisen later in the participant's life, although this is only a concern for the factors of insurance status and employment status (as compared with sex, race, and education status). Still, this limitation is not likely to have substantially altered the conclusions given the strength of the study's findings.

In conclusion, only one third of patients participate in CR following AMI despite its known health benefits. Nonparticipants are more likely to be female, black, and to have lesser degrees of education. Stressing the importance of CR participation is crucial for all post‐AMI patients, particularly these vulnerable socioeconomic populations. Increasing referral rates is only 1 part of the solution. Optimizing insurance coverage and improving access to CR programs should help to increase participation, as should optimizing referral techniques in order to maximize conversion of CR referrals to CR participation.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by American Heart Association grant 16IRG27180006 to Keeley.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007664 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007664.)

References

- 1.McMahon SR, Ades PA, Thompson PD. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2017;27:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawler PR, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Efficacy of exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation post‐myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, Taylor RS. Exercise‐based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlay SM, Pack QR, Thomas RJ, Killian JM, Roger VL. Participation in cardiac rehabilitation, readmissions, and death after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2014;127:538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doll JA, Hellkamp A, Thomas L, Ho PM, Kontos MC, Whooley MA, Boyden TF, Peterson ED, Wang TY. Effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation among older patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2015;170:855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zullo MD, Dolansky MA, Jackson LW. Cardiac rehabilitation, health behaviors, and body mass index post‐myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee BJ, Go JY, Kim AR, Chun SM, Park M, Yang DH, Park HS, Jung TD. Quality of life and physical ability changes after hospital‐based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with myocardial infarction. Ann Rehabil Med. 2017;41:121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suaya A, Shepard S, Normand T, Ades A, Prottas J, Stason B. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyden T, Rubenfire M, Franklin B. Will increasing referral to cardiac rehabilitation improve participation? Prev Cardiol. 2010;13:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzini MJ, Stevens GR, Whalen D, Ozonoff A, Balady GJ. Effect of an American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines program–based clinical pathway on referral and enrollment into cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1084–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaalema DE, Higgins ST, Shepard DS, Suaya JA, Savage PD, Ades PA. State‐by‐state variations in cardiac rehabilitation participation are associated with educational attainment, income, and program availability. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2014;34:248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mochari H, Lee JR, Kligfield P, Mosca L. Ethnic differences in barriers and referral to cardiac rehabilitation among women hospitalized with coronary heart disease. Prev Cardiol. 2006;9:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Sobolev M, Piña IL, Prince DZ, Taub CC. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation initiation and adherence in a multiracial urban population. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2017;37:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parashar S, Spertus JA, Tang F, Bishop KL, Vaccarino V, Jackson CF, Boyden TF, Sperling L. Predictors of early and late enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation, among those referred, after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:1587–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince DZ, Sobolev M, Gao J, Taub CC. Racial disparities in cardiac rehabilitation initiation and the effect on survival. PM R. 2014;6:486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005‐2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_data.htm. Accessed November 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roblin D, Diseker RA III, Orenstein D, Wilder M, Eley M. Delivery of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in a managed care organization. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravely‐Witte S, Leung YW, Nariani R, Tamim H, Oh P, Chan VM, Grace SL. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation referral strategies on referral and enrollment rates. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown TM, Hernandez AF, Bittner V, Cannon CP, Ellrodt G, Liang L, Peterson ED, Piña IL, Safford MM, Fonarow GC; American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines Investigators . Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients. findings from the American Heart Association's Get With The Guidelines Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beatty AL, Li S, Thomas L, Amsterdam EA, Alexander KP, Whooley MA. Trends in referral to cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction: data from the national cardiovascular data registry 2007 to 2012. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2582–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ades PA, Keteyian SJ, Wright JS, Hamm LF, Lui K, Newlin K, Shepard DS, Thomas RJ. Increasing cardiac rehabilitation participation from 20% to 70%: a road map from the Million Hearts Cardiac Rehabilitation Collaborative. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Thompson S, Kinmonth AL, Mant D. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction and angina: final results of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). The SHIP Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1999;318:706–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyer SJ, Earll L, Joseph S, Harrison J, Giles M, Johnston M. Increasing attendance at a cardiac rehabilitation programme: an intervention study using the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Coron Health Care. 2001;5:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grace SL, Gravely‐Witte S, Brual J, Monette G, Suskin N, Higginson L, Alter DA, Stewart DE. Contribution of patient and physician factors to cardiac rehabilitation rehabilitation enrollment: a prospective multi‐level study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsui CK‐Y, Shanmugasegaram S, Jamnik V, Wu G, Grace SL. Variation in patient perceptions of healthcare provider endorsement of cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012; 32:192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith KM, Harkness K, Arthur HM. Predicting cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: the role of automatic physician referral. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curnier DY, Savage PD, Ades PA. Geographic distribution of cardiac rehabilitation programs in the United States. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2005;25:80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaalema DE, Savage PD, Rengo JL, Cutler AY, Higgins ST, Ades PA. Financial incentives to promote cardiac rehabilitation participation and adherence among Medicaid patients. Prev Med. 2016;92:47–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]