Trends in seizures of powders and pills containing illicit fentanyl in the United States, 2018 through 2021 (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2023 May 1.

Abstract

Background:

Prevalence of fentanyl-laced counterfeit prescription pills has been increasing in the US, possibly placing a wider population at risk for unintentional exposure. We aimed to determine whether there have been shifts in the number of fentanyl seizures and in the form of fentanyl seized in the US.

Methods:

We examined quarterly national seizure data from High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas to determine the number of drug seizures in the US containing fentanyl from January 2018 through December 2021. Generalized additive models were used to estimate trends in the number and weight of pill and powder seizures containing fentanyl.

Results:

There was an increase both in the number of fentanyl-containing powder seizures (from 424 in 2018 Quarter 1 [Q1] to 1539 in 2021 Quarter 4 [Q4], β = 0.94, p < 0.001) and in the number of pill seizures (from 68 to 635, β = 0.96, p < 0.01). The proportion of pills to total seizures more than doubled from 13.8% in 2018 Q1 to 29.2% in 2021 Q4 (β = 0.92, p < 0.001). Weight of powder fentanyl seizures increased from 298.2 kg in 2018 Q1 to 2416.0 kg in 2021 Q4 (β = 1.12, p = 0.01); the number of pills seized increased from 42,202 in 2018 Q1 to 2,089,186 in 2021 Q4 (β = 0.90, p < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Seizures of drugs containing fentanyl have been increasing in the US. Given that over a quarter of fentanyl seizures are now in pill form, people who obtain counterfeit pills such as those disguised as oxycodone or alprazolam are at risk for unintentional exposure to fentanyl.

Keywords: Fentanyl, Counterfeit pills, Drug seizures

1. Introduction

There were over 115,000 overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl and its analogs) in the US between 2016 and 2019 (Hedegaard et al., 2020), and provisional counts from 2021 suggest that the number of deaths has continued to increase (Ahmad et al., 2021). Fentanyl, which is 30–50-times more potent than heroin, is a common adulterant in or substitute for powder forms of heroin (Ciccarone, 2019). However, availability of fentanyl-laced counterfeit prescription pills appears to have been increasing (US DEA Drug Enforcement Administration, 2017, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2022), possibly placing a wider population at risk for unintentional exposure. Further research is urgently needed to determine the extent to which fentanyl is appearing in pill form in particular in order to inform prevention and harm reduction efforts regarding people who are at risk for exposure.

Through January 2020, 49 US states identified the presence of fentanyl in confiscated pills with deaths attributed to use in 38 states (US DEA, 2021a). In August and September 2021, working with federal, state, and local law enforcement, the DEA seized 1.8 million fentanyl-laced pills and 712 kg of fentanyl powder (US DEA, 2021b). Fentanyl powder has been a common adulterant in drugs sold as heroin since 2014 (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Olives et al., 2017; Slavova et al., 2017), and this potent opioid has also been detected in non-opioid street drugs such as cocaine (DiSalvo et al., 2020; US DEA, 2017). What is particularly concerning is that fentanyl is now often pressed into counterfeit pills which resemble oxycodone (e.g., blue “M30′′ pills), hydrocodone, or benzodiazepines such as alprazolam (Arens et al., 2016; Armenian et al., 2017; Joynt and Wang, 2021; Sutter et al., 2017; US DEA, 2021a). This is alarming because a large portion of people who misuse psychoactive prescription pills such as opioids or benzodiazepines obtain them from nonmedical sources (McCabe et al., 2018), thus increasing the likelihood of users unintentionally ingesting fentanyl through counterfeit pills.

Further research is needed to determine the availability of illicit fentanyl in pills and powders to determine the extent of this public health threat. The DEA National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) reports significant increases in fentanyl seizures in the US between 2018 and 2020 (US DEA, 2021c), but these reports do not distinguish between pills and powders. Further, publication of NFLIS data tends to be lagged, so 2021 data are currently not available to the public. It is important to examine up-to-date trends in fentanyl seizures, as the number of fentanyl seizures, which reflect availability (US DEA, 2021a), is strongly associated with rates of synthetic opioid-involved deaths (Gladden et al., 2016; Zibbell et al., 2019). As such, we examined data collected from the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program. While a limitation of HIDTA is that detection of any fentanyl or fentanyl analog in seized drug product is coded as a fentanyl seizure, given that exposure to even small amounts of fentanyl can lead to overdose (with 2 mg being an estimated lethal dose) (US DEA, 2022; US Sentencing Commission, 2017), detection of any fentanyl in a seized drug product is an important indicator for overdose risk. This is the first study to examine trends in the form of fentanyl – pill versus powder – seizures in the US between 2018 and 2021.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

Congress created the HIDTA program to assist federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies within areas determined to be critical drug trafficking regions in the US. There are 33 HIDTAs in 50 states and the District of Columbia (HIDTA, 2019). HIDTAs collect data on drug seizures made by participating agencies. The HIDTA Performance Management Process collects data quarterly from all HIDTAs. Through a collaboration between HIDTA and the National Drug Early Warning System (Cottler et al., 2020), data were examined from seizures of fentanyl and its analogs collected from January 2018 through December 2021.

2.2. Statistical analyses

Generalized additive models testing linear, quadratic, and cubic basis functions were used to fit regression splines with automated selection of knots to visually capture nonlinear quarterly trends, plotted with 95% confidence intervals for model predictions. We then tested polynomial terms up to cubic for each outcome and chose the best fitting model for each trend. This secondary data analysis did not involve human subjects and was exempt from review by the NYU Langone Medical Center institutional review board.

3. Results

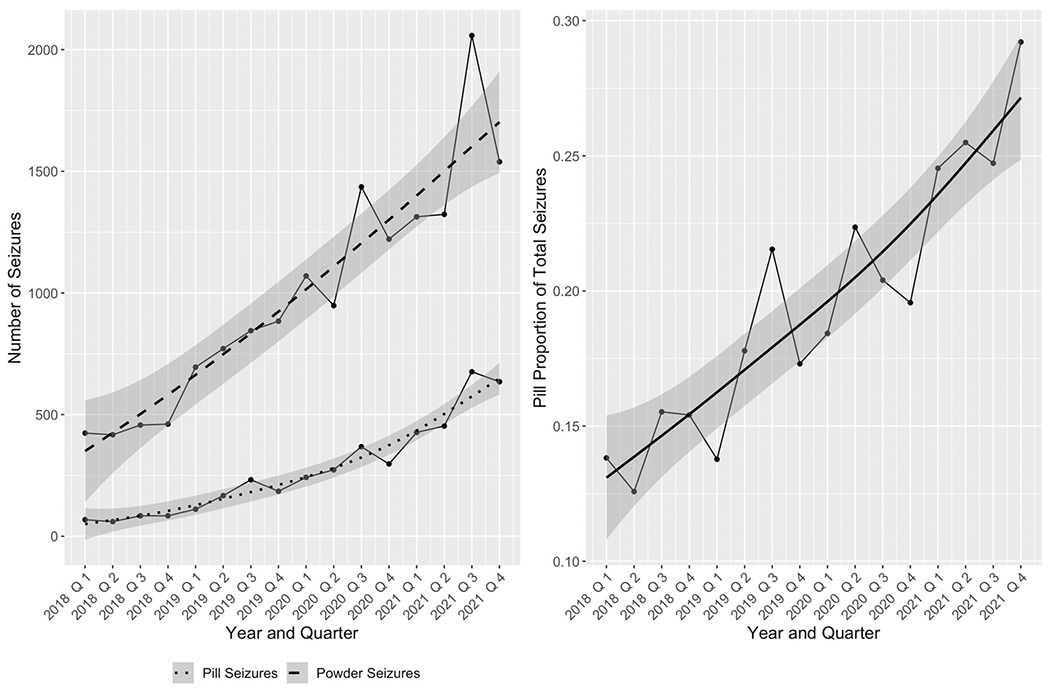

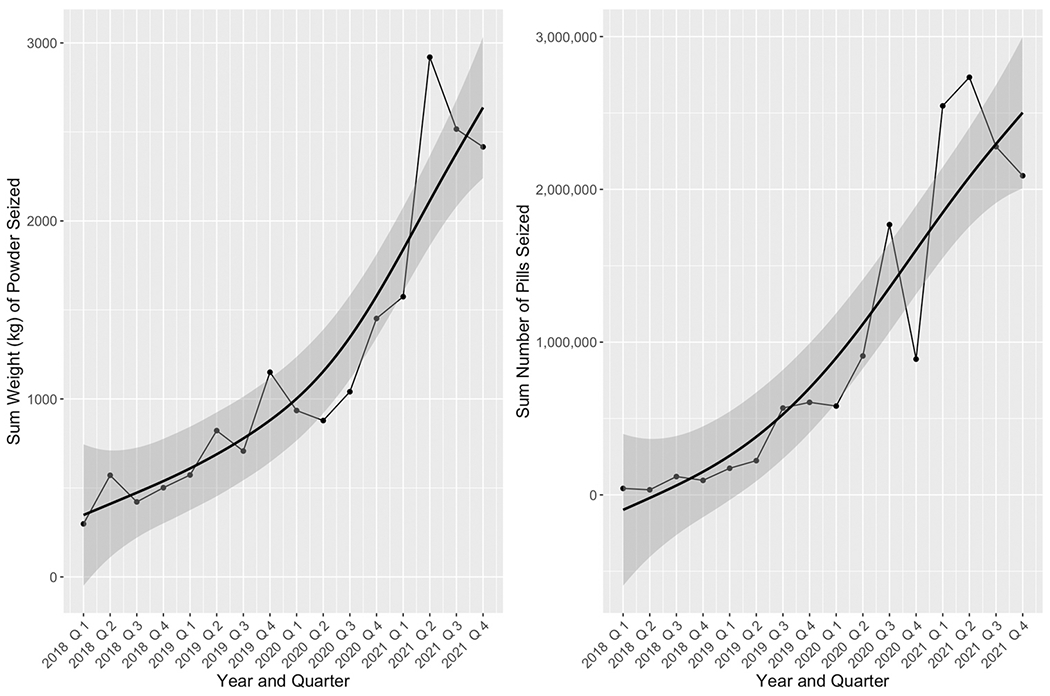

There was a linear increase in the number of fentanyl-containing powder seizures (from 424 in 2018 Quarter 1 [Q1, January through March] to 1539 in 2021 Quarter 4 [Q4, October through December], β = 0.94, standard error [SE]= 0.09, p < 0.001, a 263.0% increase) and a quadratic increase in the number of pill seizures (from 68 to 635, β = 0.96, SE=0.24, p < 0.01, a 833.8% increase) (Fig. 1). The proportion of pills to total seizures more than doubled from 13.8% in 2018 Q1 to 29.2% in 2021 Q4 (β = 0.92, SE=0.10, p < 0.001, an 111.6% relative increase). With respect to weight of seizures (Fig. 2), weight of powder fentanyl seizures increased in a quadratic manner from 298.2 kg in 2018 Q1 to 2416.0 kg in 2021 Q4 (β = 1.12, SE=0.38, p = 0.01, an 710.2% increase); the number of pills seized increased from 42,202 in 2018 Q1 to 2,089,186 in 2021 Q4 in a linear manner (β = 0.90, SE=0.12, p < 0.001, a 4850.4% increase).

Fig. 1. :

Trends in number of seizures involving fentanyl powders and pills and trend in proportion of pills seized out of all fentanyl seizures, 2018 through 2021.

Fig. 2. :

Trends in weight of fentanyl powder seized and number of fentanyl-containing pills seized, 2018 through 2021.

4. Discussion

Fentanyl-related deaths have continued to increase in the US (Ahmad et al., 2021) so more timely national indicators, especially regarding supply, are sorely needed to help with targeted prevention and harm reduction efforts. More research focusing on fentanyl seizures in particular has been needed as this can help determine the extent of illicit fentanyl availability in the population. We estimated trends in seizures of pills and powders in the US containing fentanyl between 2018 and 2021. Results suggest that there was an increase both in the number of fentanyl-containing powder seizures and in the number of pill seizures, with the proportion of pills to total seizures more than doubling within this time period.

Seizures of both pills and powders containing fentanyl have been increasing in the US. What is particularly alarming is that as of 2021, over a quarter of illicit fentanyl seizures were in pill form. Fentanyl can be present in counterfeit versions of common drugs such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and alprazolam (Arens et al., 2016; Armenian et al., 2017; Joynt and Wang, 2021; Sutter et al., 2017; US DEA, 2021a); therefore, people who purchase such purported drugs are at risk for unintentional exposure to fentanyl. Unintentional exposure to fentanyl increases risk for overdose death (Hempstead and Phillips, 2019), and exposure is particularly risky among opioid-naïve individuals who consume counterfeit benzodiazepines as such users may face the combined risk of low tolerance to opioids as well as synergistic effects from two sedative classes (Aldy et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2012; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2021).

Our results corroborate NFLIS data (US DEA, 2021) and a previous smaller study which found that while cannabis and methamphetamine seizures initially dropped during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and then rebounded, fentanyl seizures continued to increase across the pandemic without such a dip (Palamar et al., 2021a). As such, fentanyl availability did not appear to be greatly impacted during COVID-19; in fact, it increased consistently. Ongoing surveillance of fentanyl seizures is important as this can guide public health response.

In this analysis, we used seizure data to indicate level of fentanyl availability. This, in some respects may seem counterintuitive as seizures are actually intended to disrupt drug supply and thus decrease availability. However, studies have shown mixed results regarding seizures and drug availability. While some seizure efforts have been found to be associated with drug droughts along with increased prices and/or decreased purity, other studies have shown little effect of seizures themselves on actual availability (Pardo, 2020). Given that we detected increases in seizures coincide with increasing synthetic opioid-related death rates (Ahmad et al., 2021), and given increasing illicit production, the perceived abundance of fentanyl, and ease of transport to and within the US (US DEA, 2021a), it is more than plausible that while seizures may lead to immediate local decreases in availability, they more so highlight greater overall availability in the US.

Public education about the risk of non-pharmacy-sourced pills containing fentanyl needs to be more widespread. A recent study of nightclub and dance festival attendees—a population at high risk for illicit substance use—estimated that in 2019, 52.9% agreed that pharmaceutical pills from non-pharmacy sources can contain fentanyl (Palamar et al., 2021b). Agreement was lowest among gay/lesbian (35.4%) and Hispanic participants (44.0%), and highest among those who had engaged in nonmedical use of benzodiazepines (65.7%) or opioids (65.0%) in the past year or engaged in past-year use of cocaine (65.7%) or ecstasy (55.3%). These findings suggest that a substantial portion of people who use illegal drugs appear to be aware that non-pharmacy-sourced pills can contain fentanyl, but less experienced people who may be at risk for use require more education. Both public and peer education are needed, not only regarding potential risk of unintentional exposure to fentanyl, but also regarding how to reduce harm and how to respond to related overdoses (Latkin et al., 2019). An important part of such response would likely be increased access to naloxone.

At the individual-level, drug checking in particular (e.g., via fentanyl test strips) can help people who use drugs detect the presence of fentanyl in their drug product and help them decide whether or not a drug may be particularly unsafe to use (Dasgupta and Figgatt, 2021; Palamar et al., 2020; Peiper et al., 2018). In the US, the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act (also known as the “RAVE Act”) has served as a deterrent against drug checking services at nightlife venues since its enactment in 2002 (Palamar et al., 2019). Syringe exchange programs have been a leading method of fentanyl test strip distribution (Park et al., 2021a); however, as of 2021, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) began to allow federal funding to cover the costs of fentanyl test strips (SAMHSA, 2021). Further, many local departments of health have begun promoting use of test strips. As such, these recent shifts suggest both wider availability and acceptability of such tests. The US, however, lacks systematic drug checking at the national level. Semi-systematic drug checking is more common in European countries—some by which individuals can drop off or send their drug samples to be analyzed (Brunt et al., 2016) and others in which checking has become more standard at dance festivals (Measham, 2019). The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) has also began presenting aggregated drug checking findings from various agencies in their recent annual reports (EMCDDA, 2021). More systematic research—particularly real-time monitoring—focusing on drug checking results in the US could better inform public health at the population level.

Finally, real-time drug surveillance can inform the public as new drug trends are rapidly introduced (Ciccarone et al., 2017), and utilizing crime lab data for this purpose, examining vicissitudes in type and combination of substances in circulation, holds promise as an early warning system in overdose prevention (Rosenblum et al., 2020). Monitoring a combination of drug seizures, drug checking results, self-reported use, as well as poisonings and deaths related to use can help provide the most complete picture of the epidemiology of fentanyl use during this time of increasing availability.

4.1. Limitations

Data are not available on what confiscated drugs were purported to be when seized, and data only show whether or not fentanyl was detected in seized products. As such, we could not differentiate seized drugs by purity or co-occurrence of other substances. For example, our data could not differentiate whether seizures were solely fentanyl or of fentanyl combined with another drug such as cocaine (Park et al., 2021b). However, even small amounts can be fatal, and according to the US DEA, 42% of pills they tested contained at least 2 mg, which is thought to be a fatal dose (US DEA, 2022). As such, while many pills may only contain trace amounts of fentanyl, a sizeable portion can have fatal effects if ingested–particularly by opioid-naïve users. Fentanyl analog seizures were also coded by HIDTAs as fentanyl seizures so we could not differentiate regarding which drugs seized contained fentanyl versus fentanyl analogs. Many fentanyl analogs are as potent or more potent than fentanyl, but some, however, are not as potent (Suzuki and El-Haddad, 2017). Finally, we could not acquire data regarding what seized pills containing fentanyl were pressed to represent (e.g., oxycodone, alprazolam). Expanding technical analysis of drug seizures to include purity, co-occurrence of other substances, markings or brandings, as well as making available these data to researchers and policy makers would aid in public health surveillance and intervention.

4.2. Conclusions

Seizures of drug products containing fentanyl have been increasing in the US. Given that over a quarter of fentanyl seizures are now in pill form, people who obtain counterfeit pills such as those disguised as prescription opioids or benzodiazepines in particular are at risk for unintentional exposure to fentanyl. Prevention and harm reduction efforts are needed to help prevent unintentional overdose among those at risk for fentanyl exposure through counterfeit pills.

Acknowledgments

J. Palamar is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01DA044207), as is L. Cottler (U01DA051126), and D. Ciccarone (R01DA054190).

Role of funding source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U01DA051126, R01DA044207, and R01DA054190. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Palamar has consulted for Alkermes. Dr. Ciccarone reports personal fees from Celero Systems and Motley Rice LLP outside the submitted work. Dr. Keyes reports personal fees related to expert work in litigation. The authors have no other potential conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors are responsible for this reported research. J. Palamar conceptualized and designed the study. C. Rutherford conducted the statistical analyses under mentorship from K. Keyes. All authors interpreted results, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. The authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P, 2021, Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: ⟨https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm#citation⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Aldy K, Mustaquim D, Campleman S, Meyn A, Abston S, Krotulski A, Logan B, Gladden MR, Hughes A, Amaducci A, Shulman J, Schwarz E, Wax P, Brent J, Manini A, 2021. Notes from the field: Illicit benzodiazepines detected in patients evaluated in emergency departments for suspected opioid overdose - four states, October 6, 2020-March 9, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep 70 (34), 1177–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arens AM, van Wijk XM, Vo KT, Lynch KL, Wu AH, Smollin CG, 2016. Adverse effects from counterfeit alprazolam tablets. JAMA Intern Med 176 (10), 1554–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenian P, Olson A, Anaya A, Kurtz A, Ruegner R, Gerona RR, 2017. Fentanyl and a novel synthetic opioid U-47700 masquerading as street “Norco” in Central California: A case report. Ann. Emerg. Med 69 (1), 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt TM, Nagy C, Bucheli A, Martins D, Ugarte M, Beduwe C, Ventura Vilamala M, 2016. Drug Testing in Europe: Monitoring Results of the Trans European Drug Information (TEDI) Project. Drug Test. Anal 9 (2), 188–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, 2019. The triple wave epidemic: Supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. Int. J. Drug Policy 71, 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, Mars SG, 2017. Heroin uncertainties: Exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin’. Int J. Drug Policy 46, 146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Goldberger BA, Nixon SJ, Striley CW, Barenholtz E, Fitzgerald ND, Taylor SM, Palamar JJ, 2020. Introducing NIDA’s New National Drug Early Warning System. Drug Alcohol Depend. 217, 108286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Figgatt MC, 2021. Drug checking for novel insights into the unregulated drug supply. Am. J. Epidemiol 191 (2), 248–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSalvo P, Cooper G, Tsao J, Romeo M, Laskowski LK, Chesney G, Su MK, 2020. Fentanyl-contaminated cocaine outbreak with laboratory confirmation in New York City in 2019. Am. J. Emerg. Med 40, 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2021, European Drug Report 2021: Trends and Developments. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Available at: ⟨https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2021_en⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P, 2016. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep 65 (33), 837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M, 2020. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 394, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead K, Phillips J, 2019. divergence in recent trends in deaths from intentional and unintentional poisoning. Health Aff. 38 (1), 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, 2019, Annual report 2019. Available at: ⟨https://www.hidta.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AnnualReport_2019_final.pdf⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD, 2012. Polydrug abuse: A review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 125 (1–2), 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joynt PY, Wang GS, 2021. Fentanyl contaminated “M30” pill overdoses in pediatric patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med 50, 811 e3–811.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Dayton L, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE, 2019. Fentanyl and drug overdose: Perceptions of fentanyl risk, overdose risk behaviors, and opportunities for intervention among people who use opioids in Baltimore, USA. Subst. Use Misuse 54 (6), 998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ, Wilens TE, Schepis TS, 2018. Sources of prescription medication misuse among young adults in the United States: The role of educational status. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79 (2), 17m11958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measham FC, 2019. Drug safety testing, disposals and dealing in an English field: Exploring the operational and behavioural outcomes of the UK’s first onsite ‘drug checking’ service. Int J. Drug Policy 67, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2021, Benzodiazepines and Opioids. Available at: ⟨https://nida.nih.gov/drug-topics/opioids/benzodiazepines-opioids⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Olives TD, Arens AM, Kloss JS, Apple FS, Cole JB, 2017. The new face of heroin. Am. J. Emerg. Med 35 (12), 1978–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Acosta P, Sutherland R, Shedlin MG, Barratt MJ, 2019. Adulterants and altruism: A qualitative investigation of “drug checkers” in North America. Int. J. Drug Policy 74, 160–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Fitzgerald ND, Cottler LB, 2021b. Shifting awareness among electronic dance music party attendees that drugs may contain fentanyl or other adulterants. Int J. Drug Policy 97, 103353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Le A, Carr TH, Cottler LB, 2021a. Shifts in drug seizures in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 221, 108580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Salomone A, Barratt MJ, 2020. Drug checking to detect fentanyl and new psychoactive substances. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 33 (4), 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, 2020, Considering the harms drug supply indicators. RAND Working Paper. RAND Drug Policy Research Center. Available at: ⟨https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR1339.html⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Frankel S, Morris M, Dieni O, Fahey-Morrison L, Luta M, Hunt D, Long J, Sherman SG, 2021a. Evaluation of fentanyl test strip distribution in two Mid-Atlantic syringe services programs. Int J. Drug Policy 94, 103196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Rashidi E, Foti K, Zoorob M, Sherman S, Alexander GC, 2021b. Fentanyl and fentanyl analogs in the illicit stimulant supply: Results from U.S. drug seizure data, 2011-2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 218, 108416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE, 2018. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 63, 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum D, Unick J, Ciccarone D, 2020. The rapidly changing US illicit drug market and the potential for an improved early warning system: Evidence from Ohio drug crime labs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 208, 107779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavova S, Costich JF, Bunn TL, Luu H, Singleton M, Hargrove SL, Triplett JS, Quesinberry D, Ralston W, Ingram V, 2017. Heroin and fentanyl overdoses in Kentucky: Epidemiology and surveillance. Int J. Drug Policy 46, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021, Federal grantees may now use funds to purchase fentanyl test strips. Available at: ⟨https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/202104070200⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Sutter ME, Gerona RR, Davis MT, Roche BM, Colby DK, Chenoweth JA, Adams AJ, Owen KP, Ford JB, Black HB, Albertson TE, 2017. Fatal fentanyl: One pill can kill. Acad. Emerg. Med 24 (1), 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, El-Haddad S, 2017. A review: Fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 171, 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2017, Deadly Contaminated Cocaine Widespread in Florida, DEA-MIA-BUL-039–18. Available at: ⟨https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/ffles/2018–07/BUL-039–18.pdf⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2021c, National Forensic Laboratory Information System: NFLIS-Drug 2020 Annual Report. Springfield, VA. Available at: ⟨https://www.nflis.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/publicationsRedesign.xhtml⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022). [Google Scholar]

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2021a, 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment, DEA DCT-DIR-008–21. Available at: ⟨https://www.dea.gov/documents/2021/03/02/2020-national-drug-threat-assessment⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2021b, DEA seizes historic amounts of deadly fentanyl-laced fake pills in public safety surge to protect U.S. communities. Available at: ⟨https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2021/09/30/dea-seizes-historic-amounts-deadly-fentanyl-laced-fake-pills-public⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- US Drug Enforcement Administration, 2022, Facts about Fentanyl. Available at: ⟨https://www.dea.gov/resources/facts-about-fentanyl⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- US Sentencing Commission, 2017, Statement of Srihari R. Telia, Ph.D, Unit Chief, Drug and Chemical Control Unit Drug and Chemical Evaluation Section, Diversion Control Division Drug Enforcement Administration before the United States Sentencing Commission for a public hearing on fentanyl and synthetic cannabinoids. Available at: ⟨https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/amendment-process/public-hearings-and-meetings/20171205/Tella.pdf⟩ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Zibbell JE, Aldridge AP, Cauchon D, DeFiore-Hyrmer J, Conway KP, 2019. Association of law enforcement seizures of heroin, fentanyl, and carfentanil with opioid overdose deaths in Ohio, 2014-2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2 (11), e1914666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]