Salmonella Host Cell Invasion Emerged by Acquisition of a Mosaic of Separate Genetic Elements, Including Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 (SPI1), SPI5, and sopE2 (original) (raw)

Abstract

Salmonella spp. possess a conserved type III secretion system encoded within the pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1; centisome 63), which mediates translocation of effector proteins into the host cell cytosol to trigger responses such as bacterial internalization. Several translocated effector proteins are encoded in other regions of the Salmonella chromosome. It remains unclear how this complex chromosomal arrangement of genes for the type III apparatus and the effector proteins emerged and how the different effector proteins cooperate to mediate virulence. By Southern blotting, PCR, and phylogenetic analyses of highly diverse Salmonella spp., we show here that effector protein genes located in the core of SPI1 are present in all Salmonella lineages. Surprisingly, the same holds true for several effector protein genes located in distant regions of the Salmonella chromosome, namely, sopB (SPI5, centisome 20), sopD (centisome 64), and sopE2 (centisomes 40 to 42). Our data demonstrate that sopB, sopD, and sopE2, along with SPI1, were already present in the last common ancestor of all contemporary Salmonella spp. Analysis of Salmonella mutants revealed that host cell invasion is mediated by SopB, SopE2, and, in the case of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344, by SopE: a sopB sopE _sopE2_-deficient triple mutant was incapable of inducing membrane ruffling and was >100-fold attenuated in host cell invasion. We conclude that host cell invasion emerged early during evolution by acquisition of a mosaic of genetic elements (SPI1 itself, SPI5 [_sopB_], and sopE2) and that the last common ancestor of all contemporary Salmonella spp. was probably already invasive.

Salmonella spp. are enteropathogenic bacteria that cause diseases that range from a mild gastroenteritis to systemic infections. The type of disease is determined by the virulence characteristics of the Salmonella strain as well as by the host species. Detailed phylogenetic analysis by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and DNA sequencing has demonstrated that the genus Salmonella includes the two species Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica (46). S. enterica has been further subdivided into seven distinct “subspecies” (3).

Salmonellae diverged from Escherichia coli about 100 to 160 million years ago (9, 45); the different Salmonella lineages diverged about 50 million years ago (33). Data from DNA hybridization experiments indicate that Salmonella spp. harbor about 400 to 800 kb of DNA that is absent from the E. coli genome (47). Much of this additional DNA has played a role in the evolution of Salmonella as a pathogen.

Acquisition of the type III secretion system encoded in Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) is considered as a “quantum leap” in the evolution of Salmonella as a pathogen (16). This type III system allowed the bacteria for the first time to translocate effector proteins into the cytosol and to modulate signal transduction pathways within host cells (14). The SPI1 type III secretion system plays a role in the penetration of the host's ileal mucosa and the induction of diarrhea in the bovine ileum (13, 51, 53). In tissue culture experiments, the SPI1 type III secretion system facilitates induction of apoptosis in macrophages (5, 23, 38), chloride secretion (15, 42), interleukin 8 production (6, 24), membrane ruffling, and invasion into nonphagocytic host cells (14). These responses are thought to be triggered by the effector proteins, which are translocated into the host cells via the SPI1 type III secretion system. Tissue culture cell infection experiments have identified at least nine different effector proteins that are translocated into host cells via this route (1, 8, 11, 15, 18, 30, 36, 50, 54, 56). However, disruption of a single gene for a translocated effector protein has often resulted only in minor virulence defects. It has been speculated that this might be due to functional redundancy between different translocated effector proteins. According to this theory, it would be necessary to delete all redundant effector proteins mediating a certain virulence function (i.e., host cell invasiveness) in order to obtain virulence defects comparable to those observed with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mutants with a defective type III secretion apparatus. Such mutants have not been described so far. Therefore, it has been difficult to unequivocally assign virulence functions to most of the translocated effector proteins.

Phylogenetic analyses have demonstrated that the SPI1 genes encoding essential components of the type III secretion apparatus were acquired very early on when Salmonella spp. diverged from other enterobacteria (4, 35). These genes are present in S. bongori and all subspecies of S. enterica, and phylogenetic trees constructed on the basis of sequence polymorphisms detected within these genes are similar to the phylogenetic tree that had been constructed on the basis of polymorphisms in “housekeeping” proteins (4, 33, 35).

However, the translocated proteins are the actual mediators of the virulence phenotypes associated with the SPI1 type III secretion system. Therefore, acquisition of this secretion system would only be beneficial if it was accompanied by the acquisition of effector proteins mediating some basic virulence function(s). Phylogenetically old effector proteins present in all Salmonella spp. would therefore be prime candidates as mediators of central virulence functions associated with the SPI1 type III secretion system. However, the conservation of effector protein genes between diverse Salmonella lineages has not yet been analyzed.

In the present study, we have analyzed the distribution of genes for SPI1-dependent translocated effector proteins located within and outside of SPI1. The genes for translocated proteins with putative effector function located within SPI1 were present in all Salmonella spp. tested, including S. bongori and all subspecies of Salmonella enterica. The hypervariable gene avrA (18) was the only exception. Interestingly, the effector protein genes sopB, sopD, and sopE2, which are located in different regions of the Salmonella chromosome, were present in all Salmonella lineages, suggesting that these effector proteins may serve central virulence functions. Analysis of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium mutants revealed that two of these proteins are actually the mediators of invasion into nonphagocytic host cells. These data are discussed in the context of the evolution of Salmonella spp. as a pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains of the Salmonella reference collection C (SARC) (3), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 sopE+ sopE2+ sopB+ sopD+ (25), the enteropathogenic E. coli strain E 2348/69 (29), and Yersinia enterocolitica WA-C(pYV08) (22) have been described previously. Strain SARC14 did not grow and was omitted from this investigation. Shigella flexneri S1227 is a clinical isolate from a patient of the Institut für Hygiene und Mikrobiologie (Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany). S. enterica serovar Typhi X3744 was provided by J. E. Galán (Yale University, New Haven, Conn.).

All recombinant Typhimurium strains used in this study are derivatives of S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 (25). Strains carrying mutations in sopE (SB856 sopE sopE2+ sopB+ sopD+) (20) or invG (SB161 sopE+ sopE2+ sopB+ sopD+) (31) were generously provided by J. E. Galán. Strains M200 sopE+ sopE2 sopB+ sopD+ and M202 sopE sopE2 sopB+ sopD+ have been described previously (50). M201 sopE+ sopE2 sopB+ sopD+ was constructed by integration of the suicide vector pGP704 (Ampr), carrying the internal fragment bp 17 to 655 of sopE2 from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 into the chromosome of strain SL1344 (S. Stender and W.-D. Hardt, unpublished observations).

To disrupt the sopD gene, the suicide vector pM506 (Tetr) was integrated into the chromosome of SL1344 by single recombination, yielding M500 sopE+ sopE2+ sopB+ sopD. To obtain an in-frame deletion of sopB, the suicide vector pM508 (Tetr) was integrated into the chromosome of SL1344 by single recombination, followed by a second recombination forced by selection on sucrose plates, yielding M509 sopE+ sopE2+ sopB sopD+. The strain M516 sopE sopE2 sopB sopD+ was constructed by repeated phage P22-mediated transduction of the sopE::aphT allele of SB856 (20) and the _sopE2::_pM218 allele (Tetr) of M200 (50) into M509 (described above). M511 sopE sopE2 sopB sopD was constructed by sequential phage P22-mediated transduction of the sopE::aphT allele of SB856 (20), the _sopE2::_pM219 allele (Ampr) of M201 (Stender and Hardt, unpublished), and the _sopD::_pM506 allele of M500 (described above) into M509 sopE+ sopE2+ sopB sopD+ (described above).

The gene disruptions and deletions were confirmed by Western blot analyses with polyclonal antisera directed against SopE (37), SopB (this study), or SopE2 (50); by PCR; and by Southern blot analyses.

For all functional assays, bacteria were grown for 12 h in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 0.3 M NaCl, diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and grown for another 4 h under mild aeration to reach an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.9.

Southern blot hybridization.

Chromosomal DNA of bacterial strains was prepared by standard protocols with the QIAamp DNA Mini kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). The chromosomal DNA was digested with _Eco_RV (unless stated otherwise), run on 0.8% agarose gels, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) by capillary blotting according to standard protocols (49). The DNA probes used for hybridization were random-prime labeled with exonuclease-free Klenow polymerase and fluorescein-modified dUTP as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham/Pharmacia). Hybridization was performed at 56°C (unless stated otherwise) in a buffer containing 0.75 M NaCl, 75 mM sodium citrate (pH 7), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% dextran sulfate, and 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The hybridization signals were detected with an α-fluorescein–horseradish peroxidase conjugate and a chemiluminescent substrate according to protocols provided by the manufacturer (Amersham/Pharmacia).

The following DNA probes were prepared by PCR as described in Table 1, with chromosomal DNA from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 or S. enterica serovar Typhi X3744 as a template. The following temperature cycles were used: sopB, sipC, and sipB, 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; sipA, sptP, and sopD, 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 51°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min; cysI, p120, and hpaB, 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min; and probe a (Fig. 1D) and probe b (Fig. 1D), 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min.

TABLE 1.

DNA probes for Southern blot hybridizations

| Probe | Size | Organism | PCR primera or cloned DNA fragment | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sipC | 1.2 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ATGTTAATTAGTAATGTGGGA | This study |

| TTAAGCGCGAATATTGCCTGC | ||||

| sipBc | 1.4 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | CTAAAAACGGCGGAGACA | This study |

| AATCGTTTCGCCCATCA | ||||

| sipA | 1.8 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | CCGCAGTCAGAGCAAAGT | This study |

| TGCAATCTCAGCCAGTTTT | ||||

| sptP | 1.5 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | AGTATTAACCTGGCTTGGAAAA | This study |

| CAAACTGTGAGGCGTCTTCC | ||||

| avrA | 1 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | _Eco_RV fragment of pSB1136 | Hardt and Galán, unpublished |

| sopBb | 1.7 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | TGCTCTAGACATGCAAATACAGAGCTTCTATCA | This study |

| AAGCTTGGCATAAAGGGACAGCACA | ||||

| sopD | 1 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhi | TAAGCTTCGGTAATCATCAAA | This study |

| TGCACCCATCTTTACCAAT | ||||

| sopE | 723 bp | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | _Acc_65I-_Xba_I fragment of pSB1167 | Hardt and Galán, unpublished |

| sopE2 | 723 bp | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | _Eco_RI-_Xba_I fragment of plasmid pM202 | 50 |

| cysI | 1.35 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | GGGCGGGGTGATTACTA | This study |

| CCGCTTCACGCTCTTTC | ||||

| p120 | 1.3 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhi | GGACGCCTTTCTGACACA | This study |

| ATCGGTTGATGCTGGAAA | ||||

| hpaB | 1.35 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | TTAACGGGCGAAGAGTATT | This study |

| TGGCTGCCCGAGTAGTT | ||||

| Probe a | 1 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhi | GTTCGGCGCTCAGTCC | This study |

| AACGGCGAAAGCAAGAT | ||||

| Probe b | 1.3 kb | S. enterica serovar Typhi | TCGTACCCAGGAGTCACATA | This study |

| CCCTGGCCTGAGAGAATC |

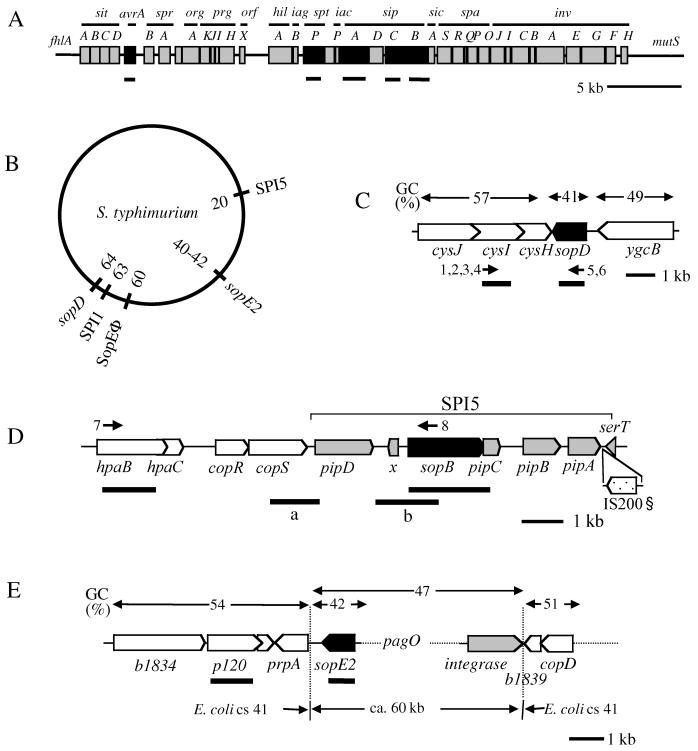

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal loci encoding effector proteins translocated via the SPI1 type III secretion system. Genes encoding known translocated effector proteins are shown in black, other genes in the loci (islands) are shaded gray, and adjacent genes with strong similarity to genes from E. coli are shown in white. Positions of primers (black arrows) and probes (black bars) used for mapping the loci are indicated (Table 1). (A) SPI1. (B) Chromosomal map of S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium showing the locations of SPI1 and several effector protein genes located outside of SPI1. SopEΦ, the lysogenic bacteriophage encoding SopE, is integrated into the chromosome of several Typhimurium strains at the indicated site (37). SopB is encoded within SPI5 (55). (C) Map of the sopD region as derived from reference 30 and from the S. enterica serovar Typhi genome sequence (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/st). (D) Map of SPI5, which encodes the translocated effector protein SopB. § indicates the position of an IS_200_ insertion element present in the SPI5 sequence of S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhi (information from the Sequencing Project at the Sanger Center; figure adapted from reference 55), but absent from SPI5 from serovar Dublin (accession no. AF060858). (E) Map of the sopE2 region as inferred from the S. enterica serovar Typhi genome sequence (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/st). sopE2 (black) forms the left border of a ca. 60-kb inserted region with little similarity to E. coli sequences. An ORF (gray) with sequence similarity to integrases from lambdoid phages is located at the right border of this inserted region. ORFs with sequence similarity to genes from the centisome 41.2 to 41.6 region of the E. coli chromosome are shown in white.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Cloning of DNA fragments was performed according to standard protocols (49). Coding regions of sopB genes from Salmonella strains SARC7, SARC10, and SARC11 were retrieved by PCR with primers designed on the basis of the Dublin sopB sequence (accession no. AF060858; 5′-TGCTCTAGACATGCAAATACAGAGCTTCTATCA and 5′-AAGCTTGGCATAAAGGGACAGCACA; 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min) and cloned into the _Eco_RV site of pMOSBlue (Amersham/Pharmacia), yielding pM53 (SARC7), pM52 (SARC10), and pM62 (SARC11).

PCR primers to amplify sopD were designed on the basis of the Dublin sequence (accession no. AF060858; 5′-CGGGATCCAGCGCAGATAAAGAAAAAGC and 5′-GCTCTAGAAAGCGAGTCCTGCCATTC; 34 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 51°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min). PCR products were cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen), yielding the vectors pM56 (SARC7), pM57 (SARC10), and pM58 (SARC11).

sopE2 primers were designed on the basis of the Typhimurium sequence (accession no. AF217274; 5′-CTCTTTCATAACGATTTTCTCAGC and 5′-GGATATCAAAGGTAATGCGAGTAA; 34 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min). PCR products were cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector, yielding the vectors pM59 (SARC7), pM60 (SARC10), pM61 (SARC11), and pM63 (SARC12). The sequences were determined by using three independent clones, the Ready Reactions Dye Deoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), and an Applied Biosystems model 377XL automated sequencer.

PCR analysis of the sopD region (Fig. 1C) was done with the following primers: primer 1, 5′-GGGCGGGGTGATTACTA; primer 2, 5′-GCGACCACCGATGAAGA; primer 3, 5′-CGGCGGATAACACGATT; primer 4, 5′-CCGCCAGACCTTCCAG; primer 5, 5′-CGGGATCCAGCGCAGATAAAGAAAAAGC; and primer 6, 5′-CAGCGCAGATAAAGAAAAAG. The primer combinations were as follows: primers 1 and 5 (ca. 3.3-kb product), SARC1, SARC2, SARC7, SARC8, SARC9, SARC10, SARC13, SARC15, and SARC16; primers 2 and 5 (ca. 2.3-kb product), SARC3 and SARC4; primers 3 and 6 (ca. 2.4-kb product), SARC5; and primers 4 and 6 (ca. 3-kb product), SARC11 and SARC12 (with 34 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 51°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 5 min). PCR analysis of the SopB/SPI5 locus (Fig. 1D) was performed with the following primers: primer 7, 5′-TTAACGGGCGAAGAGTATT; and primer 8, 5′-TTCCGGCTTTATTTTTACC (with 34 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 11 min). The PCR products were 8.5 kb for strains SARC1, SARC2, SARC5, SARC6, SARC7, SARC8, SARC9, SARC10, SARC11, SARC15, and SARC16 and 6 kb for strain SARC13. For construction of the suicide vector pM506, an internal fragment (bp 73 to 604) of sopD from Typhimurium SL1344 was obtained by PCR (primers 5′-CGGGATCCAGCGCAGATAAAGAAAAAGC and 5′-GCTCTAGAAAGCGAGTCCTGCCATTC; 33 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 20 s) and cloned into the suicide vector pSB377 (Tetr oriR6K) (31).

A chromosomal DNA fragment from Typhimurium SL1344 harboring the open reading frames (ORFs) of sopB and pipC, including 368 bp located upstream of sopB and 814 bp downstream of pipC, was amplified by PCR (primers 5′-CCCAAGCTTTCGTCACGGTCTTACTTGTCC and 5′-GCGGCCGCCCGTTGACATCCTCCAGAA; 33 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min) and cloned into pACYC184 (NEB), yielding the low-copy SopB expression vector pM515. The construct was verified by DNA sequence analysis.

To construct a suicide vector for deletion of sopB, we amplified the sequences located directly upstream (primers 5′-CGGGATCCGCGTTACGCAATCACTATC and 5′-GCTCTAGAAGCCTCCTGGGTTTTTAGTGA; 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 3 min) or downstream of sopB (primers 5′-GCTCTAGAAAAAATTTATCGCCAGAGGTG and 5′-GCGGCCGCCCGTTGACATCCTCCAGAA; 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 3 min) by PCR and cloned the PCR products into pBluescript SKII+ (Stratagene), yielding pM502 and pM503. The inserts of both vectors were verified by DNA sequence analysis. The insert of pM502 was cloned into pM503, yielding pM505, and the resulting insert was subcloned into the _Bam_HI and _Not_I sites of the suicide vector pSB890 (a derivative of pGP704; oriR6K Tetr sacAB) (W.-D. Hardt and J. E. Galán, unpublished observations), yielding the suicide vector pM508 used for deletion of sopB.

Gentamicin protection assay.

COS7 tissue culture cells were grown for 2 days in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in 24-well dishes to reach 80% confluency. The culture medium was removed, and 500 μl of Hanks' buffered salt solution (HBSS) was added 3 min before addition of the bacteria. Bacteria were grown for 12 h in LB medium supplemented with 0.3 M NaCl, diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and grown for another 4 h under mild aeration to reach an OD600 of 0.9. The number of CFU per milliliter was determined by plating appropriate dilutions on LB agar. To start the assay, bacteria were added to COS7 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 and incubated for 50 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were washed three times with HBSS and incubated in a mixture of 500 μl of DMEM, 5% FBS, and 400 μg of gentamicin per ml for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were washed three times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed in 1× PBS–0.1% Na-deoxycholate, and the number of intracellular bacteria (CFU) was determined by plating on LB agar. To allow direct comparison, the CFU were corrected for the number of the bacteria of the inoculum. The invasiveness of the wild-type strain was set equivalent to 100%, and the invasiveness of the mutant strains was calculated as a percentage of that of the wild type. The numbers given were determined in at least six independent experiments for each strain.

Macrophage cytotoxicity assay.

J774 tissue culture cells were grown on glass coverslips for 2 days in DMEM–10% FBS in 24-well dishes to reach 80 to 90% confluency. Culture medium was replaced with 500 μl of HBSS 3 min before addition of the bacteria. Bacteria were grown for 12 h in LB medium supplemented with 0.3 M NaCl, diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and grown for another 4 h under mild aeration to reach an OD600 of 0.9. To start the assay, J774 cells were infected at an MOI of 10 and incubated for 45 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were washed three times with HBSS and stained with ethidium homodimer (Molecular Probes [2 μM in HBSS]) for 25 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Afterwards, the cells were washed twice with HBSS and examined for nuclear staining by fluorescence microscopy. In three independent experiments, at least 300 cells were evaluated for each bacterial strain. The cytotoxicity of the wild-type strain (number of ethidium homodimer-stained cells/total number of cells evaluated) was normalized to 100%, and the cytotoxicity of the mutant strains was calculated as a percentage of that of the wild type.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the sopE2, sopD, and sopB genes analyzed have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: sopE2, AF323070 (SARC7), AF323071 (SARC10), AF323072 (SARC11), and AF323073 (SARC12); sopD, AF323074 (SARC7), AF323075 (SARC10), and AF323076 (SARC11); and sopB, AF323077 (SARC7), AF323078 (SARC10), and AF323079 (SARC11).

RESULTS

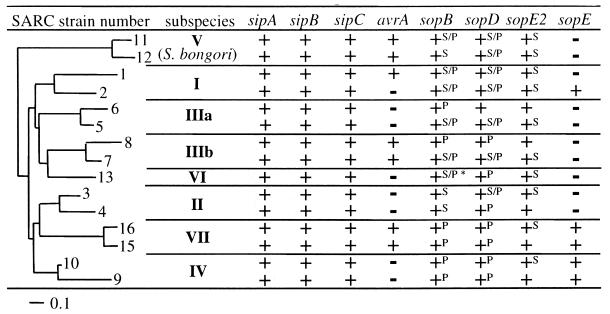

Except for avrA, all effector protein genes located within SPI1 are present in all Salmonella spp.

SPI1 encodes a type III translocation system, as well as several proteins (including AvrA, SptP, SipA, SipD, SipC, and SipB), which are secreted and/or translocated into the host cell (Fig. 1A). SipB, SipC, and SipD are necessary for efficient delivery of effector proteins into host cells (8). In addition, SipB may also have some effector function that induces cell death in host cells (23, 39). SipC has also been suggested to have an effector function related to the invasion process (21 [however, see below]). SipA is capable of stabilizing polymerized actin structures and supporting bacterial entry (56). SptP has a tyrosine phosphatase and GTPase activation domain thought to be involved in the deactivation of host cell Rho GTPases during later stages of the invasion process (12, 32).

In earlier studies, the genes (invH, invE, invA, spaM/invI, spaN/invJ, spaO, spaP, and spaQ) encoding functional components of the secretion apparatus located in the right half of SPI1 were shown to be highly conserved among all Salmonella spp. (4, 35, 44). However, it has remained unclear whether the effector proteins encoded within this island are also conserved. Therefore, we have analyzed the distribution of these translocated effector proteins in the SARC collection, which includes 15 Salmonella strains of the subspecies I (includes the animal-pathogenic serovars Typhimurium and Typhi), II, IIIa, IIIb, IV, V (S. bongori), VI, and VII (3) (Table 2). The phylogenetic relationship between these strains is well established (3). Chromosomal DNA of the Salmonella strains of the SARC collection was digested with _Eco_RV and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with probes corresponding to the ORFs of sipA, sipB, sipC, and sptP (Fig. 1A and Table 1). Although we have detected restriction fragment length polymorphisms (data not shown), each strain of the SARC collection yielded hybridization signals of similar strength with each of the four probes (Table 2). Chromosomal DNA from Yersinia enterocolitica WA-C(pYVO8), Shigella flexneri S1227, and the enteropathogenic E. coli strain 2348/69, which also contain type III translocation systems, did not yield any detectable hybridization signals. Therefore, the genes for the effector proteins encoded within SPI1 are highly conserved between all Salmonella strains, but are much less similar or absent in other enteropathogenic bacteria.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of genes for SPI1-dependent effector proteinsa

We also analyzed the distribution of the avrA gene. This gene is located at the left border of SPI1 and is flanked by genes for two regulatory proteins on one side and a gene cluster encoding a putative iron transport system on the other side (10, 28, 57). AvrA encodes a translocated protein with putative effector function that is similar to AvrRxv (accession no. L20423) and AvrBsT (accession no. AF156163) from Xanthomonas campestris pathovar Vesicatoria and the apoptosis-inducing effector proteins YopP and YopJ from Yersinia spp. (accession no. L33833, AF023202, and AF074612). Southern hybridization with an avrA probe demonstrated that avrA is present in isolates from subspecies I, IIIb, and VII, while it is absent in the other strains tested (Table 2). There was no obvious correlation between the patterns of distribution of avrA among these strains and their phylogenetic relationship (Table 2). This is in line with an earlier study which had revealed that avrA is present in only some strains of S. enterica subspecies I, while it was absent from others (18). These data provide further evidence to support the hypothesis that avrA was acquired (by horizontal gene transfer) and/or deleted by some Salmonella strains well after divergence of Salmonella spp. from their last common ancestor. In contrast, the effector protein genes located in the core of SPI1 are highly conserved and were probably acquired early on before the divergence of the different Salmonella lineages.

Analysis of the distribution of Sop effector proteins among diverse Salmonella spp.

During the past 4 years, a number of effector proteins have been identified that are translocated by the SPI1 type III secretion system, but which are encoded in distant regions of the Salmonella chromosome (Fig. 1B) (1, 15, 20, 30, 36, 50, 52, 54). For most of these effector protein genes, it remains unclear when they were acquired during evolution and how well they are conserved among highly diverse Salmonella spp. Therefore, we analyzed the presence of sopB, sopD, sopE, and sopE2 and their chromosomal localization in the strains of the Salmonella SARC collection.

sopB is located at equivalent chromosomal regions in all Salmonella lineages.

sopB is located within SPI5 in the centisome 20 region of the Salmonella chromosome (55) (Fig. 1B and D). sopB encodes a 62-kDa translocated effector protein with phosphatidylinositol phosphatase activity (42), which has been implicated in host cell invasion (26) and the induction of chloride ion secretion and diarrhea (42, 55). We have determined by Southern blot hybridization with a probe corresponding to the sopB coding sequence (Table 1) that this gene is present in every single isolate of the SARC collection (Table 2).

The chromosomal location of the sopB genes (SPI5) was analyzed by PCR (primers 7 and 8; see Materials and Methods and Fig. 1D) and Southern blotting with probes specific for sopB and hpaB as well as probes a and b (Fig. 1D and Table 1). The results are summarized in Table 2 and demonstrate that sopB is located in the same chromosomal region in all strains tested (ca. 7.5 kb downstream of hpaB) (Table 2) (data not shown). However, in strain SARC13, we detected a 2.5-kb deletion between the left border of SPI5 and hpaB (data not shown). In conclusion, our data show that sopB was already present in the last common ancestor of all contemporary Salmonella spp.

sopD is located at equivalent chromosomal regions in all Salmonella lineages.

sopD encodes a 40-kDa protein translocated into host cells via the SPI1 type III system (30). SopD has been proposed to act in concert with SopB to induce diarrhea in bovine infections (30). Earlier studies had shown that sopD is present in several isolates belonging to Salmonella enterica subspecies I (30). By Southern blot analysis with a probe derived from the sopD coding sequence from S. enterica subspecies I serovar Dublin (Table 1), we have shown here that sopD is conserved not only within subspecies I, but also between all subspecies of S. enterica and the S. bongori isolates from the SARC collection (Table 2). In contrast, other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae did not yield hybridization signals (data not shown).

As judged from the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi genome sequence, sopD is located at centisome 64 of the Salmonella chromosome about 40 kb from the right border of SPI1 (Fig. 1B and C). sopD has a significantly lower GC content than the flanking regions, and it is inserted between two ORFs with sequence similarity to cysH (30) and ygcB, two genes located directly adjacent to each other in the E. coli K-12 chromosome (2).

The chromosomal location of the sopD locus was analyzed by Southern blotting (probes corresponding to cysI and sopD; Table 1 and Fig. 1C) and PCR (primers 1 to 6; see Fig. 1C and Materials and Methods). Our results (Table 2) demonstrate that sopD is located at the same chromosomal location about 1 kb downstream of cysI in all Salmonella strains of the SARC collection tested. Therefore, sopD and sopB must have been present already in the last common ancestor of all contemporary Salmonella spp.

sopE is highly variable, whereas the sopE2 locus is present in all Salmonella lineages.

In S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium, SopE is encoded by a temperate bacteriophage of the P2 family integrated at centisome 60 of the chromosome (20, 37). Upon translocation, SopE binds to the small G proteins Cdc42 and Rac1 and mediates cytoskeletal rearrangements that are sufficient to facilitate bacterial invasion (19, 48). Interestingly, sopE was detected only in some strains of Salmonella enterica subspecies I, and the few Typhimurium isolates carrying sopE belong to a strain responsible for a major epidemic in the 1970s and 1980s (37). However, how sopE is distributed among highly diverse Salmonella spp. remained unclear. Southern blot analysis with a sopE probe revealed that this gene was present in strains belonging to subspecies I, IV, and VII (Table 2). No hybridization signals were obtained with chromosomal DNA from other enterobacteria harboring type III secretion systems (data not shown).

SopE2 is a 25-kDa translocated effector protein about 70% identical to the G nucleotide exchange factor SopE (1, 50). It is involved in the recruitment of the Arp2-3 complex and the induction of membrane ruffling, and it is sufficient to mediate bacterial invasion (50). In contrast to sopE, sopE2 has been identified in all S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium strains analyzed (50). sopE2 has a much lower GC content than the adjacent chromosomal region (Fig. 1E). It is encoded at centisome 40 at the left border of a ca. 60-kb chromosomal region with little similarity to E. coli sequences (Fig. 1E). The distribution of sopE2 among Salmonella enterica subspecies and Salmonella bongori isolates had previously been unknown.

By Southern blot hybridization with a probe corresponding to the sopE2 coding sequence, we show here that sopE2 is present in every isolate of the SARC collection (Table 2). Hybridization conditions were sufficiently stringent to avoid detection of sopE genes present in some of the strains tested (see Materials and Methods). In addition, no hybridization signals were observed with chromosomal DNAs from other enterobacteria (data not shown).

The chromosomal location of sopE2 in the different Salmonella spp. was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with sopE2 and p120 probes (Fig. 1E). The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 2. The results demonstrate that sopE2 (and possibly the entire 60-kb inserted DNA region) is present and located at equivalent chromosomal positions (i.e., the centisome 40 to 42 region) in all Salmonella spp. Our data suggest that sopE2, like sopB and sopD, was already present in the last common ancestor of all contemporary Salmonella lineages. In contrast, sopE must have been transferred horizontally in multiple cases well after divergence of the contemporary Salmonella lineages.

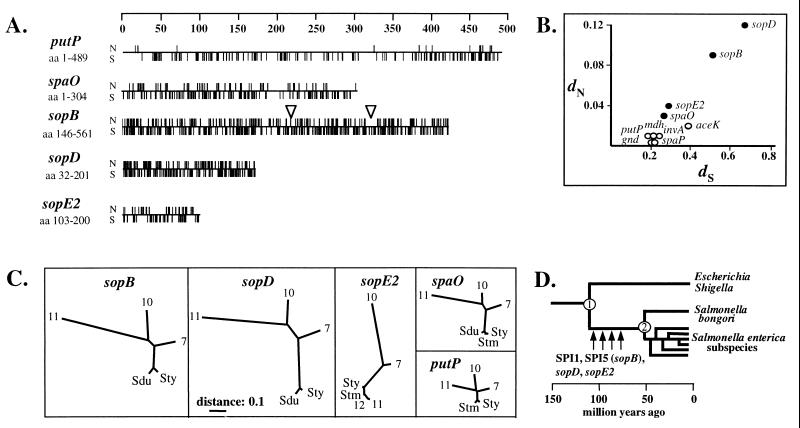

Phylogenetic analysis of sopB, sopE2, and sopD

A phylogenetic analysis was performed to investigate the process of adaptation by acquisition of additional translocated effector protein genes in more detail. We have determined the DNA sequence of parts of the coding regions of sopB (nucleotides [nt] 434 to 1686), sopE2 (nt 306 to 599), and sopD (nt 93 to 603) from Salmonella strains SARC7 (S. enterica subspecies IIIb), SARC10 (S. enterica subspecies IV), and SARC11 (S. bongori; see Materials and Methods). These sequences were compared to the sopB, sopE2, and sopD sequences from the S. enterica subspecies I serovars Typhimurium, Typhi, and Dublin (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of genes encoding effector proteins translocated via the SPI1 type III secretion system of Salmonella spp. Sequences (see Materials and Methods) were aligned and analyzed for nucleotide exchanges at synonymous and nonsynonymous sites by using the SNAP package (40). (A) Linear plot showing the positions of polymorphic nucleotides at synonymous (S) and nonsynonymous (N) sites. (B) Estimated pairwise numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous nucleotide site (_d_S) and nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (_d_N) for sopB, sopD, and sopE2 sequences. For comparison, we have also included the data for the SPI1 type III machinery genes spaO, invA, and spaP, as well as the data for several housekeeping genes (putP, gnd, mdh, and aceK) (35). (C) Unrooted phylogenetic trees. Trees were constructed based on the synonymous nucleotide exchanges with the SNAP and Phylip program packages. The scales have been adjusted to allow direct comparison of the phylogenetic data for the different genes. For comparison, we have redrawn the phylogenetic trees for spaO and putP, which had been published before (35), by the same procedure. (D) Schematic representation of the evolution of host cell invasion by Salmonella spp. (adapted from reference 43). The published sequences have the following accession numbers: sopB sequences, Salmonella enterica subspecies I (Typhimurium, AF021817; Dublin, U90203); putP sequences, SARC1 (Typhimurium), L01135; SARC2 (Typhi), L01134; SARC7, L01146; SARC10, L01143; SARC11, L01148; spaO sequences, Salmonella enterica subspecies I (Typhimurium, U29364; Dublin, U29345; Typhi, U29363), SARC7, U29348; SARC10, U29358; SARC11, U29359. For other sequences, see Materials and Methods.

The most notable feature is a high incidence of nonsynonymous nucleotide exchanges (i.e., polymorphic amino acid positions) in sopB (33.1%), sopD (39.4%), and, to a lesser extent, sopE2 (23.7%) (Fig. 2A) compared to the level in housekeeping genes like putP (2.66%). Accordingly, the _d_N (mean number of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions per nonsynonymous site) is much higher for sopB (_d_N = 0.09), sopD (_d_N = 0.12), and sopE2 (_d_N = 0.04) than for housekeeping genes (_d_N ≤ 0.02 for putP, gnd, mdh, and aceK) and genes encoding components of the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus (invA and spaP (Fig. 2B). The _d_N for sopB, sopD, and sopE2 is even higher than that for spaO (_d_N = 0.03), which encodes a protein detectable in Salmonella culture supernatants and which serves some essential function in the type III secretion mechanism (7, 35). Increased nucleotide exchange rates at nonsynonymous positions (leading to alterations in the amino acid sequence) are often observed for genes of pathogenic bacteria that encode proteins that are under strong diversification selection (i.e., by the hosts' immune system or by functional requirements concerning the specificity for certain targets in host cellular signaling cascades; see reference 35 for a discussion).

Despite the considerable sequence variation among the sopB genes from diverse Salmonella spp., two inositol phosphate 4-phosphatase consensus motifs (42) were strictly conserved in all sequences analyzed. These consensus motifs are important for the biological function of SopB from S. enterica subspecies I serovar Dublin (42). This argues that the basic molecular function of SopB has remained unchanged after the divergence of the contemporary Salmonella lineages.

In comparison to housekeeping genes or genes located within SPI1, the overall number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous nucleotide site (_d_S) is somewhat increased for the sequenced parts of sopB (_d_S = 0.51) and sopD (_d_S = 0.68) (Fig. 2B). However, it is unclear whether these differences are significant, because the sequenced fragments (especially of sopD) are fairly short, and regions with similar _d_S values are also found in the other genes analyzed (codons 50 to 170 of spaO; codons 380 to 480 of putP).

Unrooted phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the observed synonymous (silent) nucleotide exchanges in the coding sequences (Fig. 2C). For comparison, we have also included the unrooted trees for spaO (35) and the housekeeping gene putP (41). Overall, the topology of the unrooted phylogenetic trees obtained for the translocated effector protein genes is strikingly similar to that for the housekeeping gene putP and for the SPI1 gene spaO (Fig. 2C), indicating that no horizontal transfer of these genes between the different Salmonella lineages had occurred after diversification into S. bongori and the different S. enterica subspecies. The sopE2 gene from S. bongori (SARC11 and SARC12) is the only exception: it is very similar to the sopE2 genes from S. enterica subspecies I strains. Therefore, sopE2 must have recently been transferred between S. enterica subspecies I strains and S. bongori.

Overall, our data confirm that sopB, sopD, and sopE2, along with SPI1, were acquired during the early phase of Salmonella evolution after divergence from E. coli (about 100 to 160 million years ago) (9, 45) (Fig. 2D), but before the divergence of S. bongori from the S. enterica lineages (some 50 million years ago) (33) (Fig. 2D).

SopB, SopE, and SopE2 are crucial for host cell invasion.

Analysis of the E. coli genome sequence has demonstrated that genes are acquired and lost at a rate of about 31 kb per million years and that the average introduced gene persists for only 14.4 million years (33, 34). Our data presented above demonstrate that sopB, sopD, and sopE2 have persisted for at least 50 million years and are still present in all contemporary Salmonella lineages. This indicates that sopB, sopD, and sopE2 may have been stabilized in the Salmonella chromosome by providing some key virulence function. However, Salmonella strains carrying single mutations in either sopB, sopD, or sopE2 (or sopE) were only mildly attenuated in tissue culture virulence assays or experimental animal infections (1, 20, 26, 30, 50, 54, 55). These mild defects were generally much weaker than the defects observed with Salmonella mutants harboring an inactivated SPI1 type III translocation apparatus. Interestingly, Salmonella double mutants with disrupted sopB and sopD genes or with disrupted sopE and sopE2 genes had a stronger virulence defect than either of the single mutants (30, 50). This led us to speculate that there might be considerable functional redundancy between several translocated effector proteins encoded outside of SPI1. According to this hypothesis, it would be necessary to inactivate all redundant effector proteins in order to analyze a certain virulence function (i.e., host cell invasion) mediated by the SPI1 type III secretion system. To test this hypothesis, we have disrupted the genes encoding SopB, SopD, and SopE2 in the same Typhimurium strain (see Materials and Methods). These experiments were performed in a _sopE_-negative genetic background (SB856 = Typhimurium SL1344, sopE::aphT) (20), because it is known that sopE alone is sufficient to mediate tissue culture cell invasion (19).

In accordance with earlier results, disruption of sopB, sopD, sopE, or sopE2 alone had little effect on the ability of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium to invade tissue culture cells, as measured by a gentamicin protection assay. (Table 3) (1, 20, 26, 30, 50, 54, 55; data not shown). Inactivation of sopE and sopE2 (M202) resulted in a threefold-reduced ability to invade tissue culture cells. However, a triple mutant with inactivated sopE, sopE2, and sopB genes (M516) was 100-fold less invasive than the isogenic wild-type strain. This invasion defect was almost as severe as the invasion defect (600-fold attenuation) of a Typhimurium mutant with a disrupted SPI1 type III secretion apparatus (i.e., SB161 [_ΔinvG_]) (Table 3). The invasion defect was complemented by transformation with SopE2 (pM149) and SopE (pSB1130) expression vectors and, to a lesser extent, with a SopB expression vector (pM515) (Table 3). The slight differences in the levels of complementation with the SopE and the SopE2 expression vectors might be due to subtle differences in the amounts of protein expressed or translocated from both plasmids. The low complementation efficiency of the SopB vector is probably due to improper expression or translocation, as indicated by the experiments described below. Inefficient complementation with SopB expression vectors has been described before (15). In conclusion, three effector proteins encoded outside of SPI1 jointly mediate host cell invasion.

TABLE 3.

Several effector proteins cooperate to mediate host cell invasion

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Invasiveness (%)a | Macrophage cytotoxicity (%)b | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL1344 | Wild type | 100 | 100 | 25 |

| SB856 | sopE | 53.3 ± 29 | 94 | 19, 20 |

| M202 | sopE sopE2 | 28.4 ± 3.9 | 86 | 50 |

| M516 | sopE sopE2 sopB | 0.95 ± 1.0 | 90 | This study |

| M511 | sopE sopE2 sopB sopD | 0.93 ± 0.4 | 85 | This study |

| M516(pM149) | sopE sopE2 sopB (p_sopE2_) | 80.8 ± 31 | 87 | This study; 50 |

| M516(pSB1130 | sopE sopE2 sopE (p_sopE_) | 213.0 ± 81 | 90 | This study; 19, 20 |

| M516(pM515) | sopE sopE2 sopB (p_sopB_) | 12.2 ± 1.2 | 17 | This study |

| SB161 | invG | 0.17 ± 0.1 | 3 | 31 |

A quadruple mutant of Typhimurium with inactivated sopE, sopE2, sopB, and sopD genes_,_ M511, was as deficient in tissue culture cell invasion as the triple mutant strain M516. In line with previous results (30), sopD does not seem to affect tissue culture cell invasion.

Absence of SopB, SopD, SopE, and SopE2 does not affect macrophage cytotoxicity.

Typhimurium strains induce rapid cell death in macrophages in an SPI1-dependent manner (5, 23, 38). Effector proteins translocated via the SPI1 secretion system are thought to mediate this effect, and the translocated effector protein SipB has been shown to play a key role in this process (23). Therefore, the macrophage cytotoxicity assay can provide a sensitive tool to verify whether a certain Typhimurium mutant is still capable of efficiently translocating effector proteins (i.e., SipB) into host cells. None of the Typhimurium strains carrying mutations in sopB, sopD, sopE2, and/or sopE showed any significant defect in macrophage cytotoxicity (Table 3). Low levels of macrophage cytotoxicity were only observed when M516 was complemented with a SopB expression vector (pM515), suggesting that the presence of this vector may interfere with efficient translocation of other effector proteins (Table 3). Disruption of invG, which encodes an integral component of the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus, completely alleviated macrophage cytotoxicity. These data indicate that the function of the SPI1 type III secretion system is not impaired even by the introduction of mutiple mutations in genes encoding translocated effector proteins. Furthermore, we have shown by Western blot analysis that expression and secretion of the effector protein SipC into Salmonella culture supernatants are not affected in any of the effector protein-deficient mutants (data not shown). Therefore, the invasion defect observed with the sopE sopE2 sopB triple mutant M516 is solely attributable to the absence of SopB, SopE, and SopE2.

DISCUSSION

Acquisition of the type III secretion system encoded within SPI1 has been considered as a key step during the evolution of Salmonella spp. as pathogens (17), and the genes encoding essential components of the SPI1 type III secretion apparatus are highly conserved among all Salmonella lineages (35). However, it had remained unclear whether genes for effector proteins that directly mediate key virulence funtions are conserved to a similar extent.

We have found that two groups of genes encoding SPI1-dependent effector proteins are present in all Salmonella lineages. The first group of effector protein genes is located in the core region of SPI1 and includes sipA, sipB, sipC, and sptP. Surprisingly, several effector protein genes located outside of SPI1 are also present in all Salmonella lineages. This second group of genes includes sopB, sopD, and sopE2. They are located in chromosomal regions that are absent from the E. coli genome (30, 55; this paper) (reviewed in reference 27). The GC content of these effector protein genes and their flanking regions is always significantly lower than the overall GC content of the Salmonella chromosome. This low GC content is generally viewed as an indicator for genes that have been acquired from other species by horizontal gene transfer. Southern hybridization, PCR, and sequence analyses showed that the genes of the effectors SopB, SopD, and SopE2 map to identical positions of the chromosome in all Salmonella spp. and that sopB, sopD, and sopE2 must have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer in the period after divergence of Salmonella from E. coli (100 to 160 million years ago) (9, 45) and before the divergence of the contemporary Salmonella lineages (ca. 50 million years ago) (33).

These “old” effectors encoded outside of SPI1 may have coevolved with the type III secretion system and with the effectors encoded within SPI1. Therefore, the “old” effectors may actually mediate central virulence functions ascribed to the SPI1 type III secretion system. Indeed, mutation analysis demonstrated that SopB and SopE2 are the mediators of Salmonella invasion into host cells. In the Typhimurium strain SL1344, which was used in these studies, the sopE gene was also involved. A triple mutant (M516) was more than 100-fold less invasive than the wild-type strain. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that the type III secretion system encoded within SPI1, the two conserved effector proteins SopB and SopE2, and (in the case of S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344) the variable effector protein SopE form a functional unit that mediates host cell invasion and that may be described as an “invasion virulon.”

The data presented above indicated that the SPI1 SopB SopE2 invasion virulon is conserved among all Salmonella lineages. Therefore, it was surprising to find frameshift mutations in the sopE2 genes from both S. enterica subspecies 1 serovar Typhi strains analyzed (50). However, both of these strains belong to the few Salmonella spp. that harbor functional sopE genes (50; unpublished results). SopE and SopE2 are both G-nucleotide exchange factors for Cdc42 of the host cells, and transfection experiments have shown that each of these two effectors is sufficient to mediate bacterial invasion (19, 50). Therefore, it is conceivable that the presence of the sopE gene may have alleviated the need for a functional sopE2 gene in serovar Typhi. In conclusion, originally, host cell invasion was mediated largely by the effector proteins SopB and SopE2, and both effectors are still involved in this process in “modern” Salmonella spp. In some instances, however, other effectors with redundant function have been added or even replaced one of these “old” effector proteins.

What is the evidence for horizontal transfer of effector protein genes between different Salmonella lineages? In accordance with earlier data (18, 20, 37), we found that two of the effector protein genes analyzed (avrA and sopE) were present in only some Salmonella strains of the SARC collection, while absent from others. Because homologs of avrA have been identified in a number of gram-negative bacteria, including animal and plant pathogens, it seems reasonable to assume that avrA had been acquired by horizontal gene transfer from some other bacterial species. SopE, on the other hand, does not show any appreciable sequence similarity to any other protein, except for SopE2 from Salmonella spp. Based on this observation, it has been proposed that sopE was derived from Salmonella sopE2 by gene duplication (1). Because avrA and sopE genes were detected in several distantly related Salmonella spp., both genes must have been transferred in multiple cases well after the divergence of the different Salmonella lineages.

Are there additional effector proteins involved in Typhimurium host cell invasion? The triple mutant strain M516 is still about sixfold more invasive in COS7 tissue culture cells than a mutant with a disrupted SPI1 type III secretion system (SB161 = SL1344, ΔinvG) (Table 3). This suggests that S. enterica subspecies I serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 may still express one or more additional effector proteins involved in host cell invasion. It is unclear whether any of the effector proteins encoded within SPI1 or maybe additional effector proteins encoded at distant locations of the chromosome may be involved. Two translocated effector proteins encoded within SPI1 have already been implicated in the modulation of the host cell cytoskeleton: the actin binding effector SipA has been shown to play a role in stabilizing and modulating the bundling of F-actin filaments (56, 57). However, induction of cytoskeletal rearrangements by SipA alone has not been demonstrated. A recent report has described de novo actin polymerization and dramatic rearrangements of the host cellular architecture by microinjection of purified SipC protein (21). Our work shows that this in vitro activity of SipC may contribute little to Salmonella invasion into tissue culture cells. The triple mutant M516 still translocates SipC into host cells, but it is completely deficient at inducing cytoskeletal rearrangements, and it is attenuated more than 100-fold in host cell invasion. However, we cannot exclude that some effector function of SipC may account for the residual invasiveness of the triple mutant M516.

In conclusion, host cell invasion by Salmonella spp. is mediated by a functional unit formed by the SPI1 type III secretion system and several effector proteins encoded in distant regions of the chromosome. Originally, internalization was mediated by the effector proteins SopB and SopE2. During divergence of the Salmonella spp. and the adaptations to new hosts, the effector protein repertoire mediating host cell invasion has changed occasionally via gene disruption by frameshift mutations, gene duplications, or acquisition of additional effector proteins with redundant function through horizontal gene transfer. The modular design of virulence functions, including the “core” SPI1 type III secretion system and a whole range of effector protein genes that mediate the actual effects by providing modules to address certain signaling pathways within host cells, provides much flexibility. This flexibility may have allowed Salmonella spp. to adapt quickly to a wide variety of different host species and may also play a role during the emergence of new epidemic strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S. Mirold and K. Ehrbar contributed equally to the experimental work described in this paper. We are grateful to Michael Hensel for critical review of the manuscript and J. Heesemann and J. E. Galán for support and scientific advice.

This work was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie to W.-D. Hardt.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakshi C S, Singh V P, Wood M W, Jones P W, Wallis T S, Galyov E E. Identification of SopE2, a Salmonella secreted protein which is highly homologous to SopE and involved in bacterial invasion of epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2341–2344. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2341-2344.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd E F, Wang F-S, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Molecular genetic relationship of the salmonellae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:804–808. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.804-808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd E F, Li J, Ochman H, Selander R K. Comparative genetics of the inv-spa invasion gene complex of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1985–1991. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1985-1991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L M, Kaniga K, Galán J E. Salmonella spp. are cytotoxic for cultured macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1101–1115. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.471410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L M, Bagrodia S, Cerione R A, Galán J E. Requirement of p21-activated kinase (PAK) for Salmonella typhimurium-induced nuclear responses. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1479–1488. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collazo C M, Galán J E. Requirement for exported proteins in secretion through the invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3524–3531. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3524-3531.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collazo C M, Galán J E. The invasion-associated type III system of Salmonella typhimurium directs the translocation of Sip proteins into the host cell. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:747–756. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3781740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doolittle R F, Feng D F, Tsang S, Cho G, Little E. Determining the divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science. 1996;271:470–477. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichelberg K, Hardt W-D, Galán J E. Characterization of SprA, an AraC-like transcriptional regulator encoded within the Salmonella typhimurium pathogenicity island 1. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:139–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, Galán J E. The Salmonella typhimurium tyrosine phosphatase SptP is translocated into host cells and disrupts the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:359–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Galán J E. A Salmonella protein antagonizes Rac-1 and Cdc42 to mediate host cell recovery after bacterial invasion. Nature. 1999;401:293–297. doi: 10.1038/45829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galán J E, Curtiss R., III Cloning and molecular characterization of genes whose products allow Salmonella typhimurium to penetrate tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6383–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galán J E. Interaction of Salmonella with host cells through the centisome 63 type III secretion system. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galyov E E, Wood M W, Rosqvist R, Mullan P B, Watson P R, Hedges S, Wallis T S. A secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin is translocated into eukaryotic cells and mediates inflammation and fluid secretion in infected ileal mucosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groisman E A, Ochman H. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell. 1996;87:791–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groisman E A, Ochman H. How Salmonella became a pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardt W-D, Galán J E. A secreted Salmonella protein with homology to an avirulence determinant of plant pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9887–9892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardt W-D, Chen L-M, Schuebel K E, Bustelo X R, Galán J E. S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell. 1998;93:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardt W-D, Urlaub H, Galán J E. A substrate of the centisome 63 type III protein secretion system of Salmonella typhimurium is encoded by a cryptic bacteriophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2574–2579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayward R D, Koronakis V. Direct nucleation and bundling of actin by the SipC protein of invasive Salmonella. EMBO J. 1999;18:4926–4934. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heesemann J. Chromosomal-encoded siderophores are required for mouse virulence of enteropathogenic Yersinia species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hersh D, Monack D M, Smith M R, Ghori N, Falkow S, Zychlinsky A. The Salmonella invasin SipB induces macrophage apoptosis by binding to caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2396–2401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hobbie S, Chen L M, Davis R J, Galán J E. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in the nuclear responses and cytokine production induced by Salmonella typhimurium in cultured intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:5550–5559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong K H, Miller V L. Identification of a novel Salmonella invasion locus homologous to Shigella ipgDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1793–1802. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1793-1802.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hueck C J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janakiraman A, Slauch J M. The putative iron transport system SitABCD encoded on SPI1 is required for full virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1146–1155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarvis K G, Giron J A, Jerse A E, McDaniel T K, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones M A, Wood M W, Mullan P B, Watson P R, Wallis T S, Galyov E E. Secreted effector proteins of Salmonella dublin act in concert to induce enteritis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5799–5804. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5799-5804.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaniga K, Bossio J C, Galán J E. The Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes invF and invG encode homologues of the AraC and PulD family of proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:555–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaniga K, Uralil J, Bliska J B, Galán J E. A secreted protein tyrosine phosphatase with modular effector domains in the bacterial pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1996;3:633–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Amelioration of bacterial genomes: rates of change and exchange. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:383–397. doi: 10.1007/pl00006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. The molecular archaeology of bacterial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9413–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Ochman H, Groisman E A, Boyd E F, Solomon F, Nelson K, Selander R K. Relationship between evolutionary rate and cellular location among the Inv/Spa invasion proteins of Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7252–7256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao E A, Scherer C A, Tsolis R M, Kingsley R A, Adams L G, Bäumler A J, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium leucine-rich repeat proteins are targeted to the SPI1 and SPI2 type III secretion systems. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:850–864. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirold S, Rabsch W, Rohde M, Stender S, Tschäpe H, Rüssmann H, Igwe E, Hardt W-D. Isolation of a temperate bacteriophage encoding the type III effector protein SopE from an epidemic Salmonella typhimurium strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9845–9850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monack D M, Raupach B, Hromockyi A E, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimurium invasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9833–9838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monack D M, Hersh D, Ghori N, Bouley D, Zychlinsky A, Falkow S. Salmonella exploits caspase-1 to colonize Peyer's patches in a murine typhoid model. J Exp Med. 2000;192:249–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;5:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson K, Selander R K. Evolutionary genetics of the proline permease gene (putP) and the control region of the proline utilization operon in populations of Salmonella and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6886–6895. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6886-6895.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norris F A, Wilson M P, Wallis T S, Galyov E E, Majerus P W. SopB, a protein required for virulence of Salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14057–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ochman H, Groisman E A. The evolution of invasion by enteric bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:555–561. doi: 10.1139/m95-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ochman H, Groisman E A. Distribution of pathogenicity islands in Salmonella spp. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5410–5412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5410-5412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ochman H, Wilson A C. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J Mol Evol. 1987;26:74–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02111283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Plikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley M, Anilionis A. Evolution of the bacterial genome. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1978;32:519–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.32.100178.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudolph M G, Weise C, Mirold S, Hillenbrand B, Baders B, Wittinghofer A, Hardt W-D. Biochemical analysis of SopE from Salmonella typhimurium, a highly efficient guanosine nucleotide exchange factor for RhoGTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30501–30509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stender S, Friebel A, Linder S, Rohde M, Mirold S, Hardt W-D. Identification of SopE2 from Salmonella typhimurium, a conserved guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Cdc42 of the host cell. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1206–1221. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsolis R M, Adams L G, Ficht T A, Bäumler A J. Contribution of Salmonella typhimurium virulence factors to diarrheal disease in calves. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4879–4885. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4879-4885.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsolis R M, Townsend S M, Miao E A, Miller S I, Ficht T A, Adams L G, Bäumler A J. Identification of a putative Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium host range factor with homology to IpaH and YopM by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6385–6393. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6385-6393.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson P R, Galyov E E, Paulin S M, Jones P W, Wallis T S. Mutation of invH, but not stn, reduces Salmonella-induced enteritis in cattle. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1432–1438. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1432-1438.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood M W, Rosqvist R, Mullan P B, Edwards M H, Galyov E E. SopE, a secreted protein of Salmonella dublin, is translocated into the target eukaryotic cell via a sip-dependent mechanism and promotes bacterial entry. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:327–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood M W, Jones M A, Watson P R, Hedges S, Wallis T S, Galyov E E. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella enteropathogenicity. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:883–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou D, Mooseker M S, Galán J E. Role of the S. typhimurium actin-binding protein SipA in bacterial internalization. Science. 1999;283:2092–2095. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou D, Mooseker M S, Galán J E. An invasion-associated Salmonella protein modulates the actin-bundling activity of plastin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10176–10181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]