Update on male erectile dysfunction (original) (raw)

Male erectile dysfunction—defined as “the inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for sexual intercourse”—is one of the most common sexual dysfunctions in men.1 Although erectile dysfunction can be primarily psychogenic in origin, most patients have an organic disorder, commonly with some psychogenic overlay.1 Some men assume that erectile failure is a natural part of the aging process and tolerate it; for others it is devastating. Withdrawal from sexual intimacy because of fear of failure can damage relationships and have a profound effect on overall wellbeing for the couple.2 Since erectile dysfunction often accompanies chronic illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, and a variety of neurological diseases, physicians from many medical disciplines will see patients with this disorder.3

Summary points

- Although around 10% of men aged 40 to 70 years have complete erectile dysfunction, only a few seek medical help

- As erectile dysfunction is frequently associated with a number of systemic illnesses and surgical treatments, a wide range of doctors must be aware of the condition in their patients

- Current effective treatments include psychosexual counselling, vacuum erection devices, intracavernosal and transurethral drug delivery, and penile prostheses

- Promising oral treatments are currently being investigated

- Both doctors and the public need to be better informed about erectile dysfunction and its treatment

Methods

The publications comprising this review were selected from a formal search of the full Medline database (using the terms erectile dysfunction, impotence, and penile erection). Articles from the authors’ personal collections are also included.

Prevalence

The Massachusetts male aging study measured several health related variables in 1290 men aged 40 to 70 years.3 Erectile dysfunction was very common. Fifty two per cent of the men reported some degree of impotence—mild in 17.1%, moderate in 25.2%, and complete in 9.6%.3 Complete impotence was reported by 5% of men at 40 years of age and 15% at 70 years of age; however, a higher prevalence of complete impotence was seen in men with concomitant illnesses. Erectile dysfunction is more common with advancing age, and since the aged population will increase, its prevalence will continue to rise.4,5

Anatomy

The penis is made up of three corpora—the ventral corpus spongiosum and the two dorsal corpora cavernosa—surrounded by the tunica albuginea. The blood supply is provided by the cavernosal arteries, which are branches of the penile artery. Branches of the cavernosal artery, the helicine arteries, open directly into the cavernous spaces. Blood drains from here into post cavernous venules, which coalesce to form larger veins that pierce the tunica albuginea before joining the deep dorsal vein, or the cavernosal and crural veins.

The penile blood vessels and trabecular smooth muscle have both motor sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation from fibres arising in the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral regions. The striated muscles outside the tunica albuginea are innervated by lumbosacral somatic nerves. Sympathetic, parasympathetic, and somatic systems act in a coordinated way. Interruption of any of these pathways, particularly the parasympathetic nerves, may preclude normal erections.6

Physiology

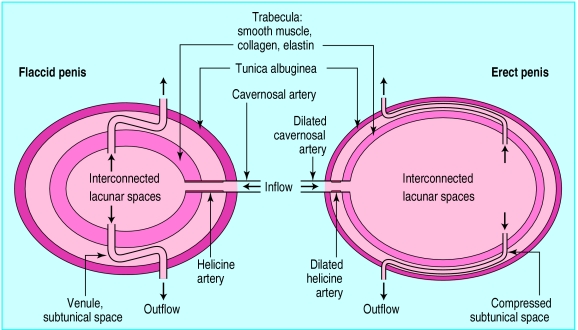

In the flaccid state, the smooth muscle cells of the penile arteries and the corpora cavernosa are in a state of tone (contraction). Relaxation of the smooth muscle (arterial and cavernosal) causes increased inflow of blood into the lacunar spaces of the corpora cavernosa (fig 1).6 The arterial pressure expands the relaxed trabecular walls, thus expanding the tunica albuginea with subsequent elongation and compression of the draining venules. This mechanism of veno-occlusion restricts the outflow of blood through these channels. After ejaculation or cessation of the erotic stimuli, the smooth muscle surrounding the arteries and the lacunar spaces contracts. The inflow of blood is reduced and the venous drainage of the corporeal spaces is opened, returning the penis to the flaccid state. Erection of the penis is thus a haemodynamic event under the control of the autonomic nervous system.7 Coordination of the neuronal activity from psychogenic stimuli occurs in the hypothalamus while reflexogenic erection involves a polysynaptic coordination in the sacral parasympathetic centres.8

Figure 1.

Hypothetical mechanism of penile erection, adapted from Krane et al2

Several neurotransmitters are involved in penile erection. A principal neural mediator of penile smooth muscle relaxation, and therefore of erection, is nitric oxide.9 Nitric oxide accounts for the biological activity of endothelial derived relaxing factor.10 It is formed from its precursor, l-arginine, by nitric oxide synthase. Nitric oxide activates guanil cyclase to form intracellular guanosine monophosphate, a potent second messenger molecule for smooth muscle relaxation. The importance of this pathway is shown by the clinical finding that selective inhibitors of phosphodiesterase-5 (which breaks down cyclic guanosine monophosphate) facilitate erection.11

Nitric oxide synthase is present in abundance in the pelvic plexus, the cavernous nerves, the dorsal penile nerves, and nerve plexuses in the cavernosal arteries and helicine arteries.12 A different isoform of nitric oxide synthase located in endothelial cells may be responsible for the relaxation of the corpus cavernosum by nitric oxide in response to haemodynamic sheer stress or bradykinin stimulation.13 Cyclic adenosine monophosphate formation is stimulated by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and prostanoids (prostaglandin I2, prostaglandin E), which also contribute to penile smooth muscle relaxation.

Aetiology of erectile dysfunction

Normal erectile function requires the coordination of psychological, hormonal, neurological, vascular, and cavernosal factors. Alteration in any one of these factors is sufficient to cause erectile dysfunction. Not uncommonly, a combination of factors is involved.2

Chronic systemic illness

Diabetes mellitus, heart disease, and hypertension are all commonly associated with erectile dysfunction.3 Results from the Massachusetts male aging study showed that the age adjusted prevalence of complete impotence was 28% in treated diabetic patients, 39% in those with treated heart disease, and 15% in men taking antihypertensive treatment. The prevalence in the whole study population was 9.6%. Complete impotence has also been observed to increase with the severity of depression; almost 90% of severely depressed men report complete impotence.3 Peripheral vascular disease leading to insufficient arterial blood supply is another common cause.14 In addition, an association between low plasma concentrations of high density lipoprotein and erectile dysfunction has been found. Other diseases such as peptic ulcer, arthritis, and allergy are also associated with an increased prevalence of erectile dysfunction.

Hormonal factors

The role of testosterone in erectile dysfunction is not clear.14 Some men continue to achieve erection even after castration.15 The fall in free serum testosterone and increases in concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin with aging may be associated with loss of libido and reduced frequency of erection, but restoration of normal testosterone concentrations does not usually improve sexual function.16 Patients with hyperprolactinaemia, frequently associated with low testosterone values, can develop low libido and erectile dysfunction by unknown mechanisms. Testosterone replacement treatment, without correction of concurrent hyperprolactinaemia, does not resolve erectile dysfunction associated with hyperprolactinaemia.14

Local conditions

Poor blood supply as a result of congenital malformations or trauma is a less common cause of erectile dysfunction that can affect the young male.14 Peyronie’s disease is a specific condition of the penis in which the development of fibrous plaques in the tunica albuginea, sometimes extending into the erectile tissue, may cause pain (in the early inflammatory stage) and penile deviation, making coitus impossible. Inability to retain pressurised blood in the corpus cavernosum follows disruption of the veno-occlusive mechanism, which can be caused by Peyronie’s disease, congenital, or the result of trauma or surgery.

Drug induced erectile dysfunction

Around 25% of erectile failure seen in clinic patients is caused by medication.17 Erectile dysfunction may affect 10-20% of patients taking thiazide diuretics, and to a lesser extent, patients who are using β blocking drugs.18 This may be a result of reduced perfusion pressure, as blood pressure falls in response to the medication, or probably a direct (but unknown) effect on smooth muscle. Further support for this mechanism comes from the observation that treatment of hypertension with the α adrenergic receptor blockers is not associated with erectile failure, and possibly even enhances pre-existing poor sexual function, despite lowering arterial blood pressure.19

Erectile dysfunction commonly complicates antidepressant treatment with both monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.17 Benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been reported to cause erectile failure, decreased libido, or ejaculatory problems.17,20 Cimetidine, digoxin, and metoclopramide cause erectile dysfunction, as do anabolic steroids, either through a direct effect on penile tissues or through suppression of normal androgen production.21

Up to 75% of patients in alcohol rehabilitation programmes have erectile dysfunction.17 In chronic alcohol abusers erectile failure may be the result of a combination of psychogenic and organic factors (for example, neuropathy).22

Psychogenic causes

Psychogenic influences are the most likely causes of intermittent erectile failure in young men. Anxiety about “performance” may result in inhibitory sympathetic nervous system activity, and anticipatory anxiety can make the condition self perpetuating.16 A psychogenic component is often present in older men, secondary to an organic cause.2 Underlying relationship problems are a common cause of erectile failure and this possibility should be explored in men of all ages.

Evaluation

A goal directed approach has been successfully used by workers such as Lue for the management of patients with erectile dysfunction.23 The patient’s medical and sexual history should be taken, and details of any concomitant medication, tobacco and alcohol consumption, and the presence of risk factors for erectile dysfunction (for example, vascular or surgical) should be noted. Preservation of nocturnal and early morning erections generally means that there is no organic basis for erectile dysfunction.16 The quality of erections during sleep can be assessed with portable home devices (such as Rigiscan) that measure changes in penile girth and rigidity, or in a sleep laboratory.

Measurement of blood pressure, palpation of peripheral pulses, and a neurological examination should be undertaken, including the bulbocavernous reflex and anal sphincter tone. The secondary sexual characteristics should be examined for signs of hypogonadism and any local abnormality in the external genitalia should be noted. The penis should be palpated for Peyronie’s plaques and the testes examined for size and consistency. Further investigations are likely to be guided by the clinical findings, but should include measurement of free testosterone and prolactin concentrations.

Vascular evaluation of the penis

A complete diagnostic investigation, and therefore a full vascular assessment, may not be important for most patients, since only a few will be treated surgically.24 The best minimally invasive method currently available for studying arterial blood supply to the penis is colour duplex Doppler ultrasound,25 which assesses the integrity of the arterial supply to the penis and provides some useful information on the veno-occlusive mechanism. More precise assessment of this mechanism requires specialised invasive tests—cavernosometry and cavernosography—which are performed if surgery is contemplated.24

Treatment options

Psychosexual counselling

Patients who have a sizeable psychogenic component may be helped by psychosexual counselling. Since the recognition that an organic element is present in most patients, this approach is increasingly being used in conjunction with pharmacological treatment.

Hormonal therapy

Testosterone may improve erectile dysfunction in some patients with diagnosed hypogonadism.2 Testosterone should not be used in eugonadal men with erectile dysfunction as it may enhance prostatic hyperplasia or promote the growth of occult prostate cancer.16 New transdermal formulations of testosterone and dihydro-testosterone, as well as oral formulations without associated liver toxicity, have been developed. Hyperprolactinaemia is usually managed with bromocryptine or similar drugs. Less commonly, surgery is used to remove tumours secreting prolactin.

Drug treatment

Drugs that are currently available have limited effectiveness. Trazodone, given as a single agent, has been effective in some studies,26 but not others.27 Side effects such as sleepiness and gastrointestinal discomfort are common and limit its use. Trazodone combined with yohimbine has been recommended, although little scientific proof of a synergistic effect exists.28 Yohimbine has a modest effect on psychogenic,29 but not on organic,28 erectile dysfunction.

New drugs, such as inhibitors of phosphodiesterase-5 that affect the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, look very promising. They are thought to work by enhancing nitric oxide mediated relaxation of the corpus cavernosal smooth muscle.30 Trials of one such drug, sildenafil, have shown a response rate of around 90% in men with erectile dysfunction of no known organic cause.31–36 In diabetic subjects with clear organic erectile dysfunction, sidenafil showed a 50% response rate.37 This drug is generally well tolerated, and has no appreciable effect on pulse rate or blood pressure.38

The dopaminergic agonist, apomorphine, produced a 60% response rate after subcutaneous injection in men with psychogenic erectile dysfunction. However, patients reported a large number of side effects. Recent formulations (a sublingual, sustained release tablet), minimise these side effects.39 Phentolamine, widely used for intracavernosal injection treatment, has been tried orally. A buccal preparation with a shorter onset of action has also been used with a success rate of 30-40%.40

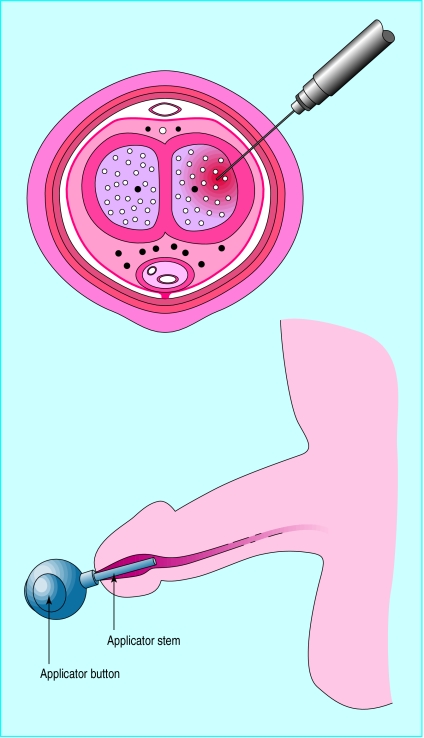

The most common treatment is self injection of prostaglandin E1 into the corpora cavernosa (fig 2). This treatment is highly effective—approximately 80% of impotent men benefit from it. It is relatively safe, with only a small risk of priapism and formation of painless penile fibrotic lesions (8-9% after two years).16 Alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) has also been administered into the urethra in men with erectile dysfunction from several causes (fig 2).41 Erection sufficient to allow intercourse was achieved by more than 40% of men, and home treatment reports indicate a good safety profile. This treatment will probably be tried as an initial step, and those who fail will then be managed with intracavernosal injections.

Figure 2.

Vasoactive drugs such as alprostadil can be injected into the penis or administered by applicator

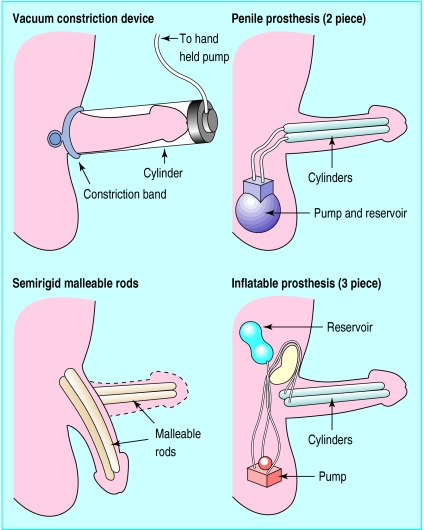

Mechanical devices

The simplest and least expensive treatment is a vacuum constriction device shown in figure 3. Air is pumped out of the cylinder with the hand held pump to create a vacuum and cause an erection. The constriction band is then pulled off the cylinder onto the base of the erect penis and the cylinder is removed. This treatment is reliable and has few adverse effects when used properly It is often accepted by older patients in a longstanding relationship, whereas younger patients may prefer to try other treatments.21 Penile prostheses are surgically implanted devices that provide penile rigidity (fig 3).16 With the two piece inflatable prosthesis, the pump and reservoir are in the scrotum and are used to inflate the cylinders into the erect position. The cylinders are then deflated by pressing a valve at the base of the pump to return the fluid to the reservoir. In a three piece inflatable prosthesis, the pump is in the scrotum and the reservoir is in the abdomen. Penile prostheses are usually recommended when other treatments fail. Semirigid, malleable rods can also be inserted into the penis to provide penile erection.

Figure 3.

Devices and prostheses to produce penile erection

Vascular surgery

Arterial reconstructive surgery is sometimes indicated in men with arterial occlusive disease, but careful selection of patients is required. The best results are obtained in young patients with isolated arterial lesions following trauma. Venous surgery, with extensive ligation of the veins that drain the corpora cavernosa, is sometimes used as the last resort before the implantation of a penile prosthesis in young men with veno-occlusive disease. The results are generally poor as only 30% of patients report long term improvement.

Conclusions

Although the ideal treatment for erectile dysfunction has not yet been found, important advances have been made. Greater openness in society has stimulated research and made it easier for patients to seek help. However, doctors are generally reluctant to discuss the topic with their patients. Training in the management of sexual dysfunction needs to improve at both undergraduate and postgraduate level. The public too requires better information about the availability of treatment.

References

- 1.Korenman SG. Advances in the understanding and management of erectile dysfunction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;60:1985–1988. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.7.7608245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krane RJ, Goldstein I, Saenz de Tejada I. Impotence. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1648–1649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912143212406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts male ageing study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zemel P. Sexual dysfunction in the diabetic patient with hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91102-2. H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin A, Babbot D. Impotence and diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1958;168:498. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.03000050010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson K-E, Wagner G. Physiology of penile erection. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:191–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christ GJ. The penis as a vascular organ. The importance of corporal smooth muscle tone in the control of erection. Urol Clin N Am. 1995;22:727–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Groat WC, Booth AM. Neural control of penile erection. In: Maggi CA, editor. The autonomic nervous system. Nervous control of the urogenital system. Vol. 6. London: Harwood; 1993. pp. 465–513. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnett AL. Role of nitric oxide in the physiology of erection. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:485–489. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer RMJ, Ferrige AJ, Moncada S. Nitric oxide accounts for the biological activitiy of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ignarro LJ, Bush PA, Buga GM, Wood KS, Fukoto JM, Rajfer J. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP formation upon electrical field stimulation cause relaxation of corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170:843–850. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett AL, Hillman SL, Chang TSK, Epstein JI, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, et al. Immunohistochemical localisation of nitric oxide synthase in the autonomic innervation of the human penis. J Urol. 1993;150:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saenz de Tejada I, Blanco R, Goldstein I, Azadzoi K, de las Morenas A, Krane RJ, et al. Cholinergic neurotransmission in human corpus cavernosum. I. Responses of isolated tissue. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H459–H467. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.3.H459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrier S, Zvara P, Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 1994;23:773–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenstein A, Plymate SR, Katz PG. Visually stimulated erection in castrated men. J Urol. 1995;153:650–652. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199503000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirby RS, Impotence: diagnosis and management of male erectile dysfunction. BMJ 1994;308:957-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.O’Keefe M, Hunt DK. Assessment and treatment of impotence. Med Clin N Am. 1995;79:415–434. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buffum J. Pharmacosexuology update: prescription drugs and sexual function. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1986;18:97–106. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1986.10471390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.TOMHS research group. Incidence and disappearance of erectile problems in men treated for stage I hypertension: the treatment of mild hypertension study (TOMHS) Eur Urol. 1996;30(suppl 2):38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balon R, Yeragani VK, Pohl R, Ramesh C. Sexual dysfunction during antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guay AT. Erectile dysfunction—are you prepared to discuss it? Postgrad Med. 1995;97:127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner G, Jensen SB. Alcohol and erectile failure. In: Wagner G. Green R, eds. Impotence: physiological, psychological, surgical diagnosis and treatment. New York: Plenum, 1981.

- 23.Lue TF. Impotence: a patient’s goal-directed approach to treatment. World J Urol. 1990;8:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li MK, Lau KO. Clinical evaluation of impotence. Ann Acad Med. 1995;24:741–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis RW, Mayda J., II Diagnosis and treatment of vasculogenic impotence. Acta Chir Hung. 1994;34:231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurt U, Ozkarde SH, Altug U, Germiyanoglu C, Gurdal M, Erol D. The efficacy of anti-serotonergic agents in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 1994;152:407–409. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32750-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meinhardt W, Kropman RF, de la Fuerte RF, Lycklama A, Nijeholt GAB, Zwartendijk J. Oral treatment of impotence, trazodone versus placebo [abstract] Int J Impotence Res. 1996;8:116. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morales A, Heaton JPW, Johnston B, Adams M. Oral and topical treatment of erectile dysfunction—present and future. Urol Clin N Am. 1995;165:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid K, Surridge DHC, Morales A, Condra M, Harris C, Owen J, et al. Double-blind trial of yohimbine in the treatment of psychogenic impotence. Lancet. 1987;ii:421–423. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90958-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boolell M, Gepi-Attee S, Gingell JC, Allen MJ. Sildenafil, a novel effective oral therapy for male erectile dysfunction. Br J Urol. 1996;78:257–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.10220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gingell C, Jardin A, Giuliano FA, Olsson AM, Dinsmore WW, Osterloh IH, et al. The efficacy of sildenafil (Viagra), a new oral treatment for erectile dysfunction, demonstrated by four different methods in a double-blind placebo-controlled, multinational clinical trial [abstract] Eur Urol. 1996;30(suppl 2):353. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eardley I, Morgan R, Dinsmore W, Pearson J, Wulff M, Boolell M. Evaluation of the efficacy of sildenafil (Pfizer UK-92,480), a new oral treatment for male erectile dysfunction (MED) in a double-blind, placebo controlled study [abstract] Eur Urol. 1996;30(suppl 2):355. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buvat JS, Gingell CJ, Jardin A, Olsson AM, Dinsmore WW, Kirkpatrick J, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra), an oral treatment for erectile dysfunction: a 1-year open-label, extension study. J Urol. 1997;157(suppl):204. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derry F, Gardner BP, Glass C, Farser M, Dinsmore WW, Muirhead G, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, single dose, two-way cross-over study in men with erectile dysfunction caused by traumatic spinal cord injury. J Urol. 1997;157(suppl):181. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lue TF Sildenafil Study Group. A study of sildenafil (Viagra), a new oral agent for the treatment of male erectile dysfucntion. J Urol. 1997;157(suppl):181. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derry F, Glass C, Dinsmore WW, Fraser M, Gardner BP, Mayton M, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra): an oral treatment for men with erectile dysfunction caused by traumatic spinal cord injury—a 28-day, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group dose-response study [abstract] Neurology. 1997;48(suppl 2):215. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boolell M, Pearson J, Gingell JC, Gepi-Attee S, Wareham K, Price D. Sildenafil (Viagra) is an efficacious oral therapy in diabetic patients with erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1996;8:186. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boolell M, Allen MJ, Ballard SA, Gepi-Attee S, Muirhead GJ, Naylor AM, et al. An orally active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int J Impotence Res. 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heaton JPW, Morales A, Adams MA, Johnston B. Recovery of erectile function by the oral administration of apomorphine. Urology. 1995;45:200–206. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(95)80005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner G, Lacy S, Lewis R. Buccal phentolamine. A pilot trial for male erectile dysfunction at three separate clinics. Int J Impotence Res. 1994;6(suppl 1):D78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padma-Nathan H, Hellstrom WJ, Kaiser FE, Labasky RF, Lue TF, Nolten WE, et al. Treatment of men with erectile dysfunction with transurethral alprostadil. Medicated urethral system for erection (MUSE) study group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701023360101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]