Low Testosterone Levels and the Risk of Anemia in Older Men and Women (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Feb 20.

Published in final edited form as: Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1380–1388. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1380

Abstract

Background

Anemia is a frequent feature of male hypogonadism and anti-androgenic treatment. We hypothesized that the presence of low testosterone levels in older persons is a risk factor for anemia.

Methods

Testosterone and hemoglobin levels were measured in a representative sample of 905 persons 65 years or older without cancer, renal insufficiency, or anti-androgenic treatments. Hemoglobin levels were reassessed after 3 years.

Results

At baseline, 31 men and 57 women had anemia. Adjusting for confounders, we found that total and bioavailable testosterone levels were associated with hemoglobin levels in women (_P_=.001 and _P_=.02, respectively) and in men (P<.001 and _P_=.03, respectively). Men and women in the lowest quartile of total and bioavailable testosterone were more likely than those in the highest to have anemia (men, 14/99 vs 3/100; odds ratio [OR], 5.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–21.8 for total and 16/99 vs 1/99; OR, 13.1; 95% CI, 1.5–116.9 for bioavailable testosterone; women, 21/129 vs 12/127; OR, 2.1; 95% CI, 0.9–5.0 for total and 24/127 vs 6/127; OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.2–9.4 for bioavailable testosterone). Among nonanemic participants and independent of confounders, men and women with low vs normal total and bioavailable testosterone levels had a significantly higher risk of developing anemia at 3-year follow-up (21/167 vs 28/444; relative risk, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.1 for total and 26/143 vs 23/468; relative risk, 3.9; 95% CI, 1.9–7.8 for bioavailable testosterone).

Conclusion

Older men and women with low testosterone levels have a higher risk of anemia.

There is evidence that testosterone influences erythropoiesis during male puberty.1 Hemoglobin levels are similar in prepubertal boys and girls but increase in boys after age 13 years, mirroring changes in testosterone concentrations. Interestingly, boys with delayed puberty have hemoglobin levels similar to those of prepubertal boys and girls, and treatment with testosterone normalizes hemoglobin levels to those observed in the late male puberty.2,3 These data suggest that testosterone contributes to the 1- to 2-g/dL difference in hemoglobin concentration between adult men and women. If testosterone stimulates erythropoiesis in adults, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a decline in testosterone levels with aging may negatively affect erythropoiesis. Accordingly, men with hypogonadism or those taking anti-androgenic drugs frequently have anemia.4–8 Conversely, diseases characterized by high testosterone levels and testosterone replacement therapy often produce a rise in hemoglobin levels that sometimes reaches the level of erythrocytosis.9–14 However, whether older men and women with low testosterone levels are at higher risk for anemia has never been fully investigated.

Using data from a population-based sample, we tested the hypothesis that older men and women with low testosterone levels are more likely to be affected by anemia and to develop anemia over a 3-year follow-up period than women with normal testosterone levels. Understanding the causes of anemia in older persons is important because anemia in older persons is frequently unexplained15 and is associated with a high risk of disability and accelerated decline of physical function.16–18

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

The InCHIANTI study19 is an epidemiologic study conducted on a representative sample of the population living in the Tuscany region of Italy. Of 1270 persons 65 years or older randomly selected from the population registry, 1155 agreed to participate, 1055 provided a blood sample, and 1036 (82% of those originally sampled eligible) had complete data for the analysis presented herein. Another 110 participants with a history or clinical evidence of cancer or gastric diseases, and 5 undergoing anti-androgen therapy, were excluded from the analysis. Finally, since our research team has demonstrated that renal insufficiency is associated with anemia only for levels of creatinine clearance lower than 30 mL/min (0.5 mL/s),20 16 participants with creatinine clearance below that level were also excluded. The study population for the cross-sectional analyses included 905 subjects (396 men and 509 women). Of these, 88 had anemia at the baseline evaluation, 126 died before the 3-year follow-up visit, and 80 refused to be reevaluated. Thus, the study population for the longitudinal analysis included 274 men and 337 women who were not anemic at baseline and were reevaluated after 3 years.

The Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging institutional review board ratified the study protocol. Participants consented to participate and to have their blood samples analyzed for scientific purposes.

BIOLOGICAL SAMPLES

At an initial home interview, participants were provided a plastic container and received detailed instructions for 24-hour urine collection. Blood samples were obtained from participants after a 12-hour fast, and after a 15-minute rest. Aliquots of serum and 24-hour urine were stored at −80 C° and were not thawed until analyzed.

HORMONE MEASUREMENT

Total testosterone level was measured using a radioimmunologic assay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, Tex), with a minimum detection limit of 0.86 ng/dL (0.03 nmol/L). In our research laboratory, intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) assessed for 3 different concentrations were 9.6%, 8.1%, and 7.8%, and 8.6%, 9.1%, and 8.4%, respectively. Sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, Calif), which has a sensitivity of 0.04 nmol/L. In our laboratory, interassay and intra-assay CVs for 3 concentrations (10.8 nmol/L, 64 nmol/L, and 116 nmol/L) were 3.1%, 5.3%, and 6.9% and 2.8%, 3.0%, and 3.6%, respectively. The serum albumin level was measured with a commercial enzymatic test (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Bioavailable testosterone values (serum free and albumin-bound testosterone but not SHBG-bound testosterone) were calculated using the Vermeulen formula.21

ANEMIA-RELATED MEASURES

Hemoglobin levels were analyzed within 4 hours of blood drawing using the autoanalyzer SYSMEX SE-9000 (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Anemia was defined according to the World Health Organization criteria22 as hemoglobin levels lower than 12 g/dL for women and 13 g/dL for men.

Erythropoietin (EPO) was measured in duplicate by Quest Laboratories (Baltimore, Md) using the Advantage EPO chemiluminescence immunoassay (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Clemente, Calif), which has a sensitivity of 1.2 mU/mL, and a CV of lower than 6%. The mean of the 2 assays was used in the analysis.

Folic acid and cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) levels were measured by a radioimmunologic assay (ICN Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY). The minimum detectable concentrations were 0.6 ng/mL for folic acid and 25 pg/mL for vitamin B12; the interassay CV was 7.1% for folic acid and 12.3% for vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 deficiency was defined as a concentration lower than 200 pg/mL; folate deficiency, as a concentration lower than 2.2 ng/mL.23

Serum ferritin and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfr) levels were measured in duplicate using chemiluminescent immunoassays (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, Ill, and Nichols Institute Diagnostics). The minimum detectable concentrations for these methods were 5 ng/mL for ferritin and 0.1 nmol/L for sTfr, with a CV of lower than 7% for both methods. The circulating iron level was assessed by a colorimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim), with a sensitivity of 5 μg/dL and a CV lower than 3%. A serum sTfr/log (ferritin) ratio above 1.5 indicated iron deficiency.24

Serum interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels were measured in duplicate by high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (BIOSOURCE, Camarillo, Calif). The lowest detectable concentration was 0.1 pg/mL, and the interassay CV was 4.5%.

COMORBID CONDITIONS

A clinician ascertained coronary heart disease (angina and myocardial infarction), congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to preestablished criteria that combined information from physician diagnoses, pharmacologic treatment, medical records, clinical examinations, and blood test results.25 Serum and 24-hour urinary creatinine levels were measured using a modified Jaffe method and were then used to calculate creatinine clearance. Body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, was based on objective measures. Smoking was coded as “ever smoked” vs “never smoked” based on self-report.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are reported as mean±SD values, medians, and interquartile ranges or percentages. Because of skewed distributions, log-transformed values for EPO and IL-6 levels were used in regression analyses. Comparisons across subgroups were performed using age-adjusted linear or logistic regression models. The relationships of total and bioavailable testosterone levels with hemoglobin levels is depicted in scatterplots using age-adjusted hemoglobin values, summarized by locally weighted polynomial regression smoothers,26 and tested in sex-specific linear regression models adjusted for multiple confounders. “Age×testosterone” and “BMI×testosterone” interaction terms were introduced in these linear models to test the hypothesis that the relationship between testosterone and hemoglobin levels is different in different age and BMI groups. Since we found no statistical evidence for such interactions, they were removed from the presented models.

The prevalence of anemia across total and bioavailable testosterone quartiles was compared by sex-specific logistic regression models, adjusted for age and multiple confounders. To capture linear and nonlinear effects, testosterone quartiles were inserted in these models both as dummy (using the upper quartile as reference) and ordinal variables (tests for trend). We hypothesized that a low testosterone level would be more strongly associated with anemia without a clear clinical cause (unexplained anemia) than with anemia accompanied by 1 or more potential causes. Thus, all cross-sectional analyses were conducted in the entire eligible population and in a “restricted” group of participants free of major causes of anemia, namely, participants with a normal circulating iron level (>60 μg/dL [10.7 μmol/L]) and no deficiency in iron ([Tfr/log (ferritin)] ratio ≤1.5), folate (<2.2 ng/mL), vitamin B12 (<200 pg/mL).15

For the longitudinal analysis, the number of “new anemia” events was too small to conduct a full analysis across quartiles. Therefore, logistic regression models were used to estimate the relative risk of developing anemia associated with total and bioavailable testosterone levels in the lowest quartile (“low” testosterone level) compared with the other 3 quartiles (“normal” testosterone level), after adjusting for age, baseline hemoglobin level, and multiple potential confounders.

All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

CROSS-SECTIONAL ASSOCIATION BETWEEN TESTOSTERONE AND HEMOGLOBIN LEVELS

Of the 396 men in the study population, 31 (7.8%) had anemia at baseline, and 20 of these had no evident causes of anemia. Of the 509 women, 57 (11.2%) had anemia, and 26 of these had no evident cause for anemia. Compared with participants with normal hemoglobin levels, men and women with anemia and especially those with “unexplained” anemia had lower total and bioavailable testosterone levels, were more likely to have a stroke history, and had higher IL-6 levels. Women with unexplained anemia also had a lower BMI than those without anemia (Table 1). In both men and women, the bioavailable testosterone level was negatively correlated with age (men, _r_=−0.34; P<.001; women, _r_=−0.11; _P_=.01) and positively correlated with BMI (men, _r_=−0.15; _P_=.003; women, _r_=−0.25; P<.001).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population*

| Men (n = 396) | Women (n = 509) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No Anemia (n = 365) | Explained Anemia (n = 11) | Unexplained Anemia† (n = 20) | No Anemia (n = 452) | Explained Anemia (n = 31) | Unexplained Anemia† (n = 26) |

| Total testosterone, ng/dL | 438 ± 119 | 355 ± 135‡ | 332 ± 121§ | 64 ± 30 | 54 ± 28 | 52 ± 27‡ |

| Bioavailable testosterone, ng/dL | 96 ± 39 | 62 ± 31[| | ](#TFN7) | 61 ± 25§ | 12 ± 9 | 9 ± 9 |

| Age, y | 73.8 ± 6.3 | 78.2 ± 6.7 | 81.4 ± 8.6 | 75.1 ± 7.0 | 81.9 ± 7.8 | 84.9 ± 9.3 |

| BMI | 27.3 ± 3.2 | 26.7 ± 2.3 | 26.3 ± 2.4 | 27.9 ± 4.4 | 26.9 ± 4.1 | 25.3 ± 3.0[| |

| Smokers | 76 (20.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (25) | 40 (8.8) | 3 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stroke | 17 (4.7) | 3 (27.3)[| | ](#TFN7) | 6 (30.0)§ | 14 (3.1) | 4 (12.9)‡ |

| Hypertension | 209 (57.3) | 7 (63.6) | 12 (60.0) | 288 (63.7) | 23 (74.2) | 18 (69.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 45 (12.3) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (15.0) | 40 (8.8) | 2 (6.4) | 2 (7.7) |

| CHD | 37 (10.1) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (15.0) | 22 (4.9) | 2 (6.4) | 2 (7.7) |

| CHF | 18 (4.9) | 18 (4.9) | 2 (10.0) | 20 (4.4) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (7.7) |

| COPD | 55 (15.1) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) |

| IL-6 median (interquartile range), pg/mL | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.2 (2.0) | 2.6 (1.9)§ | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.9 (2.6)[| |

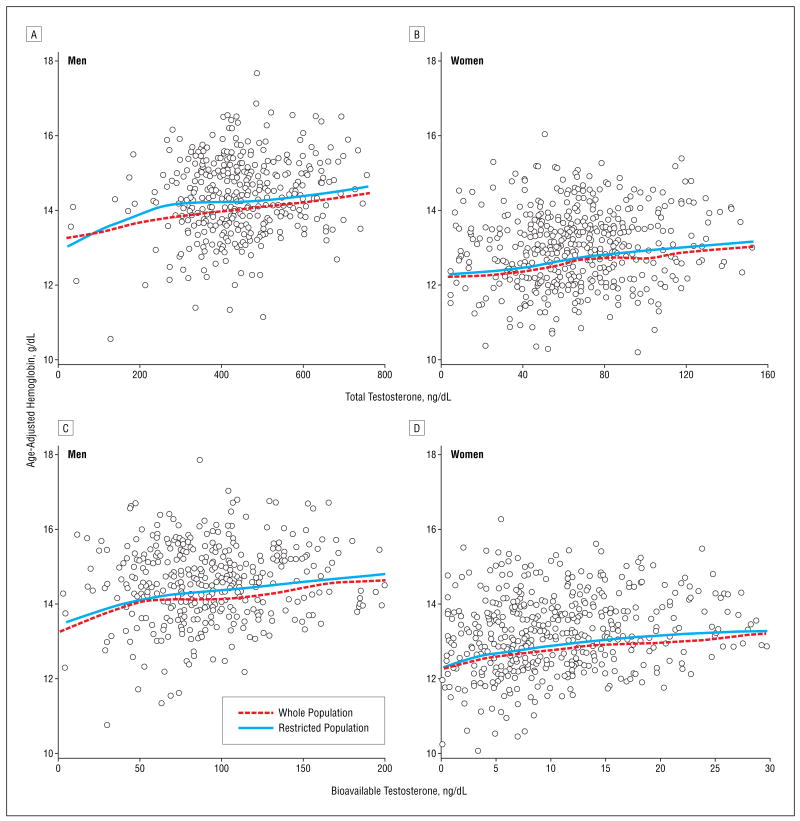

Independent of age, total and bioavailable testosterone levels were linearly correlated with hemoglobin levels (Figure 1). The regression coefficients relating serum total and bioavailable testosterone levels with hemoglobin level were larger in women than in men (Table 2), and there were significant “sex×testosterone” interactions (_P_=.03 for total and _P_=.05 for bioavailable testosterone). However, standardized regression coefficients, which estimate the average difference in hemoglobin associated with a 1-SD change in total and bio-available testosterone levels, were almost identical in the 2 sexes (Table 2). These findings were substantially unchanged after adjusting for age, BMI, smoking, creatinine clearance, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and IL-6 and EPO levels, and after restricting the analysis to 256 male and 336 female participants with normal serum iron levels and no deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, or folate.

Figure 1.

Relationship of total and bioavailable testosterone levels with hemoglobin level in all InCHIANTI19 participants and restricted to those with normal serum iron levels and no deficiencies of iron, cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12), or folate. Hemoglobin values are age adjusted. The relationships are summarized using locally weighted regression smoothers. To convert testosterone to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 0.0347.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Models for the Relationship of Testosterone Levels With Hemoglobin Levels

| Adjusted for Age | Fully Adjusted* | Fully Adjusted* and Restricted† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone Level, ng/mL | β± SE | Standardized β‡ | P Value | β± SE | Standardized β‡ | P Value | β± SE | Standardized β‡ | P Value |

| Men | |||||||||

| Total | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.14 | .002 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.17 | <.001 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.17 | .004 |

| Bioavailable | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0.12 | .02 | 0.34 ± 0.15 | 0.11 | .03 | 0.37 ± 0.17 | 0.13 | .03 |

| Women | |||||||||

| Total | 0.51 ± 0.16 | 0.14 | .001 | 0.50 ± 0.15 | 0.15 | .001 | 0.62 ± 0.19 | 0.17 | .002 |

| Bioavailable | 1.53 ± 0.50 | 0.12 | .002 | 1.21 ± 0.50 | 0.10 | .02 | 0.90 ± 0.58 | 0.10 | .13 |

CROSS-SECTIONAL ASSOCIATION BETWEEN TESTOSTERONE LEVEL AND ANEMIA

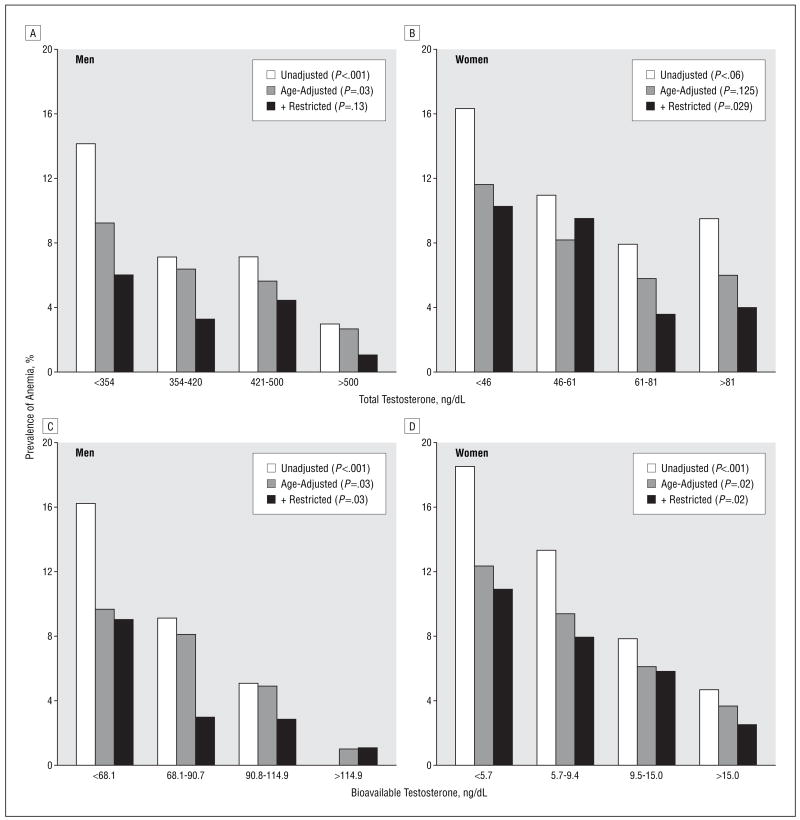

Independent of age, the prevalence of anemia was progressively higher from the highest to the lowest quartiles of total and bioavailable testosterone levels (Figure 2 and Table 3), and tests for linear trend were statistically significant, except for total testosterone level in women (_P_=.05). After adjusting for multiple confounders, we found that men in the lowest total and bioavailable testosterone level quartiles, compared with men in the highest quartile, were, respectively, 5.4 (14/99 vs 3/100; 95% CI, 1.4–21.8) and 13.1 (16/99 vs 1/99; 95% CI, 1.5–116.8) times more likely to be anemic (Table 3). Analogously, women in the lowest bioavailable testosterone level quartile were 3.4 (24/127 vs 6/127; 95% CI, 1.2–9.4) times more likely to have anemia than women in the highest quartile. In women, there was a nonsignificant trend for higher anemia prevalence from the highest to the lowest total testosterone level quartiles (from quartile 1 to quartile 4: 16.3%, 11.0%, 7.9%, and 9.5%; _P_=.12).

Figure 2.

Crude and age-adjusted prevalence of anemia according to total and bioavailable testosterone level quartiles in all InCHIANTI19 participants and restricted to cases of unexplained anemia (ie, normal serum iron levels and no deficiencies of iron, cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12), or folate. To convert testosterone to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 0.0347.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for the Likelihood of Anemia

| Adjusted for Age | Fully Adjusted* | Fully Adjusted* and Restricted† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone Level, ng/dL | OR (95% CI) | P Value for Trend | OR (95% CI) | P Value for Trend | OR (95% CI) | P Value for Trend |

| Men | ||||||

| Total | .03 | .01 | .05 | |||

| <354 | 3.7 (1.0–13.7) | 5.4 (1.4–21.8) | 6.7 (0.7–68.1) | |||

| 354–420 | 2.5 (0.6–10.0) | 2.5 (0.6–11.0) | 2.4 (0.17–32.6) | |||

| 421–500 | 2.1 (0.5–8.7) | 2.4 (0.5–10.5) | 5.1 (0.5–57.0) | |||

| >500 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Bioavailable | .01 | .01 | .01 | |||

| <68.1 | 9.7 (1.2–78.0) | 13.1 (1.5–116.9) | 5.1 (0.1–20.2) | |||

| 68.1–90.7 | 7.9 (1.0–64.6) | 12.9 (1.4–119.4) | 2.2 (0.2–27.7) | |||

| 90.7–114.9 | 4.6 (0.5–41.0) | 6.0 (0.6–58.5) | 1.7 (0.5–51.6) | |||

| >114.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0‡ | |||

| Women | ||||||

| Total | .05 | .06 | .01 | |||

| <46 | 2.0 (0.9–4.6) | 2.1 (0.9–5.0) | 4.1 (1.1–14.7) | |||

| 46–61 | 1.4 (0.6–3.4) | 1.5 (0.6–3.7) | 4.0 (1.1–15.0) | |||

| 61–81 | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 1.4 (0.3–15.8) | |||

| >81 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Bioavailable | .004 | .01 | .002 | |||

| <5.7 | 3.7 (1.4–9.8) | 3.4 (1.2–9.4) | 6.5 (1.4–29.3) | |||

| 5.7–9.4 | 2.7 (1.0–7.4) | 2.6 (0.9–7.4) | 4.6 (1.0–20.6) | |||

| 9.4–15.0 | 1.7 (0.6–5.1) | 1.7 (0.6–5.2) | 3.0 (0.6–14.0) | |||

| >15.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

In adjusted analysis on the restricted sample, the significant trend of higher anemia prevalence across total and bioavailable testosterone level quartiles was still statistically significant for both men and women. Women in the first and second testosterone level quartiles were at least 4 times (significantly) more likely to be affected by anemia than those in the highest quartiles. In spite of the significant test for trend, men in the first, second, and third total and bioavailable testosterone level quartiles were not significantly more likely to be anemic compared with those in the highest quartiles, probably because of the small sample size (Table 3). Since none of the men in the highest quartile of bioavailable testosterone level was anemic, to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) for this specific analysis, we randomly assigned the diagnosis of anemia to 1 male participant in this group. Therefore, the statistic reported in Table 3 represents a conservative estimate of the true association.

In sex-stratified logistic regression models predicting anemia and adjusted for age and levels of vitamin B12, folic acid, log(ferritin), creatinine, and log(EPO), a 1-SD higher total testosterone level was associated with 35% lower likelihood of anemia in men (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46–0.90) and 73% lower risk of anemia in women (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14–0.96). Similar findings were obtained for the bioavailable testosterone level (data not shown).

LONGITUDINAL ASSOCIATION OF LOW TESTOSTERONE LEVEL WITH ANEMIA RISK

The longitudinal analysis was conducted in 274 male and 337 female participants free of anemia at baseline who were reevaluated after 3 years. Of these, 23 men (8.3%) and 26 women (7.7%) developed anemia. Adjusting for multiple confounders, we found that men and women in the lowest total testosterone level quartile were, respectively, 1.4 (95% CI, 0.4–4.7) and 2.5 (95% CI, 1.0–6.3) times more likely to develop anemia than those in the other 3 quartiles, although in both cases the excess risk associated with a low testosterone level was not statistically significant. The risk of developing anemia associated with a low testosterone level became statistically significant (relative risk, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.1) when men and women were combined in the same analysis (Table 4). The association between low testosterone level and anemia was more robust and highly significant for the bioavailable testosterone level. After adjusting for multiple confounders, we found that men and women in the lowest bioavailable testosterone level quartile were, respectively, 4.7 (95% CI, 1.3–16.8) and 4.4 (95% CI, 1.7–11.2) times more likely to develop anemia than those in the other 3 quartiles.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models For the Risk of Developing Anemia Associated With Low Testosterone Level in Participants Free of Anemia at Baseline

| Unadjusted | Fully Adjusted* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone Level, ng/dL | 3-Year Incidence of Anemia | RR (95% CI) | P Value | RR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Men | |||||

| Total | |||||

| <354 | 9/61 (14.8) | 2.5 (1.0–6.0) | .05 | 1.4 (0.4–4.7) | .62 |

| ≥354 | 14/213 (6.6) | ||||

| Bioavailable | |||||

| <68.1 | 13/62 (21.0) | 5.4 (2.2–12.9) | <.001 | 4.7 (1.3–16.8) | .02 |

| ≥68.1 | 10/212 (4.7) | ||||

| Women | |||||

| Total | |||||

| <46 | 12/106 (11.3) | 2.0 (0.9–4.4) | .10 | 2.5 (1.0–6.3) | .06 |

| ≥46 | 14/231 (6.1) | ||||

| Bioavailable | |||||

| <5.7 | 13/81 (16.1) | 3.6 (1.6–8.1) | .002 | 4.4 (1.7–11.2) | .002 |

| ≥5.7 | 13/256 (3.9) | ||||

| Whole Sample† | |||||

| Total | |||||

| Low‡ | 21/167 (12.6) | 2.1 (1.2–3.9) | .01 | 2.1 (1.1–4.1) | .03 |

| Normal | 28/444 (6.3) | ||||

| Bioavailable | |||||

| Low‡ | 26/143 (18.2) | 4.3 (2.4–7.8) | <.001 | 3.9 (1.9–7.8) | <.001 |

| Normal | 23/468 (4.9) |

COMMENT

We found that older persons with low testosterone levels tend to have lower hemoglobin levels, are more likely to have anemia, and have a higher risk of developing anemia over a 3-year follow-up period. The risk of anemia associated with a low testosterone level and anemia was similar in the whole study population and in participants with normal serum iron levels and no deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, or folate. Both the cross-sectional and the longitudinal associations of testosterone level with anemia were stronger for bioavailable than for total testosterone level.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that directly addresses the hypothesis that a low testosterone level is a risk factor for anemia in older persons. Our findings are consistent with the frequent development of anemia in patients affected by hypogonadism or those taking anti-androgen drugs4–7 and with the fact that androgen treatment helps correct anemia in patients undergoing hemodialysis and may enhance erythropoiesis even in hypoproliferative anemia where EPO is relatively ineffective.27,28

Although the association between low testosterone level and lowered hemoglobin level was statistically significant, many participants with low testosterone levels were not anemic, and many of those who were anemic had normal testosterone levels. These findings suggest that a low testosterone level increases the susceptibility to anemia but may not be a sufficient causal factor for anemia, probably because the effect can be counteracted by alternative mechanisms. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that the testosterone level was a similar predictor of anemia in the whole study population and in participants free of potential causes of anemia, and there is evidence in the literature that anemia in older persons is multifactorial.29

The somewhat stronger association of anemia with a bioavailable rather than with total testosterone level is not surprising. In fact, SHBG and albumin levels, which considerably affect the portion of total testosterone level that is bioactive, are highly variable in older persons.21,30

The mechanism through which testosterone stimulates erythropoiesis is unclear. Testosterone enhances the proliferation of erythroid burst–forming units and colony-forming units by stimulating specific nuclear receptors, and this effect is completely abolished by pretreating marrow cells with cyproterone and flutamide, which selectively block androgen binding to nuclear androgen receptors.31 Moreover, androgens cause a sustained expansion of human female but not male erythroid progenitors.32 This is consistent with our finding that the testosterone-anemia association is stronger in women than in men. Noteworthy, using standardized regression coefficients, we found the effect of testosterone levels on hemoglobin values in men and women to be almost identical, suggesting that the testosterone-signaling pathway has different settings in men and women. Therefore, enhancements of erythropoiesis of the same magnitude require changes in testosterone levels approximately 3-fold higher in men than in women (standard deviation for total testosterone, 121 ng/dL [4.2 nmol/L] in men and 39 ng/dL [1.4 nmol/L] in women; standard deviation for bioavailable testosterone, 30 ng/dL [1.0 nmol/L] in men and 9 ng/dL [0.3 nmol/L] in women).

Also, it has been suggested that testosterone may exert its erythropoietic activity by stimulating EPO.33–35 In our analysis, a low testosterone level remained a strong significant risk factor for anemia even with adjustment for EPO levels. This is consistent with previous findings showing that the erythropoietic activity of androgens is relatively erythropoietin independent.36,37 Parallel, relatively independent mechanisms for the erythropoietic effect of androgens and EPO may explain why studies conducted in men undergoing hemodialysis found that concurrent androgen therapy greatly augmented the effectiveness of EPO treatment and reduced the EPO minimal necessary dose to maintain a satisfactory hemoglobin level.38

The main limitation of this study is that the testosterone level was measured only once. Changes in testosterone levels over the 3-year follow-up period may have considerably affected the anemia risk. Information on reticulocytes was also not available, and therefore, whether a low testosterone level is associated with reduced erythropoiesis remains unknown. Additionally, transient anemia events that occurred and reversed before the 3-year follow-up evaluation were not considered. Finally, we used the World Health Organization definition22 of anemia to make our study comparable to other studies in the literature, but the validity of using such a definition in older persons has been recently challenged.18 Our study also has strengths. We collected information on testosterone levels and other measures that, in the absence of direct assessment of bone marrow, are considered the gold standard for determining the pathophysiologic characteristics of anemia.

The results of this study have opened new questions about the pathophysiologic characteristics of anemia in older patients. We suggest that low testosterone levels could be a susceptibility factor for anemia that has been generally neglected. We suggest that low testosterone levels should be considered a potential cause or cocause of anemia in older men and women, especially when other plausible causes have been excluded, and in patients with nutritional deficiencies in whom nutritional supplementation of iron and vitamins has been ineffective. However, our findings should be confirmed in larger populations and in other clinical settings before they can be considered for clinical applications. In particular, the interplay between testosterone level and EPO in modulating erythropoiesis in older persons should be better characterized.

Recent studies have established a strong and independent relationship between hemoglobin level and many of the potential targets of testosterone supplementation, including muscle strength, muscle fatty infiltration, bone mineral density, physical performance, and cognition.16,17,39–41 The findings of the present study raise the possibility that some of the effects of testosterone supplementation may be mediated by the increased hemoglobin levels. This possibility should be carefully considered in evaluating the results of trials of androgen replacement therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The InCHIANTI study was supported as a “targeted project” (ICS 110.1\RS97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health and in part by the US National Institute on Aging (Contracts N01-AG-916413 and N01-AG-821336) and an unrestricted grant from Ortho Biotech and by the US National Institute on Aging (Contracts 263 MD 9164 13 and 263 MD 821336).

Role of the Sponsor: The granting institutions did not interfere in any way with the collection, analysis, presentation, or interpretation of the data reported in this article.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed substantially to this work. Drs Ferrucci, Maggio, Bandinelli, Valenti, Guralnik, and Longo conceived, designed, and performed the analysis and directly contributed in the writing of this article. Dr Basaria participated in the study design and critically reviewed the manuscript, providing essential endocrinologic expertise. Drs Lauretani, Ble, and Ershler participated in the interpretation of the main findings of this analysis and critically revised the manuscripts several times.

Financial Disclosure: Drs Ferrucci and Guralnik sereved as consultants for Ortho Biotech Clinical Affairs, Bridgewater, NJ, during 2003 and 2004.

References

- 1.Shahidi NT. Androgens and erythropoiesis. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:72–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197307122890205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krabbe S, Christensen T, Worm J, Christiansen C, Transbol I. Relationship between haemoglobin and serum testosterone in normal children and adolescents and in boys with delayed puberty. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1978;67:655–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1978.tb17818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hero M, Wickman S, Hanhijarvi R, Siimes MA, Dunkel L. Pubertal upregulation of erythropoiesis in boys is determined primarily by androgen. J Pediatr. 2005;146:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonseca R, Rajkumar SV, White WL, Tefferi A, Hoagland HC. Anemia after orchiectomy. Am J Hematol. 1998;59:230–233. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199811)59:3<230::aid-ajh8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ornstein DK, Beiser JA, Andriole GL. Anaemia in men receiving combined finasteride and flutamide therapy for advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 1999;83:43–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strum SB, McDermed JE, Scholz MC, Johnson H, Tisman G. Anaemia associated with androgen deprivation in patients with prostate cancer receiving combined hormone blockade. Br J Urol. 1997;79:933–941. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber JP, Walsh PC, Peters CA, Spivak JL. Effect of reversible androgen deprivation on hemoglobin and serum immunoreactive erythropoietin in men. Am J Hematol. 1991;36:190–194. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhoden EL, Morgentaler A. Risks of testosterone-replacement therapy and recommendations for monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:482–492. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold AP, Michael AF., Jr Congenital adrenal hyperplasia associated with polycythemia. Pediatrics. 1959;23:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albareda MM, Rodriguez-Espinosa J, Remacha A, Prat N, Webb SM. Polycythemia in a patient with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Haematologica. 2000;85(Eletters):E08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, et al. Older men are as responsive as young men to the anabolic effects of graded doses of testosterone on the skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:678–688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobs AS, Meikle AW, Arver S, Sanders SW, Caramelli KE, Mazer NA. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of a permeation-enhanced testosterone transdermal system in comparison with bi-weekly injections of testosterone enanthate for the treatment of hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3469–3478. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Berlin JA, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2670–2677. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Swedloff RS, Iranmanesh A, et al. Testosterone Gel Study Group. Transdermal testosterone gel improves sexual function, mood, muscle strength, and body composition parameters in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2839–2853. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104:2263–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Onder G, Ferrucci L, Wallace RB, Pahor M. Anemia and decline in physical performance among older persons. Am J Med. 2003;115:104–110. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penninx BW, Pahor M, Cesari M, et al. Anemia is associated with disability and decreased physical performance and muscle strength in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:719–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaves PH, Ashar B, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Looking at the relationship between hemoglobin concentration and prevalent mobility difficulty in older women. Should the criteria currently used to define anemia in older people be reevaluated? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1257–1264. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ble A, Fink JC, Woodman RC, et al. Renal function, erythropoietin, and anemia of older persons: the InCHIANTI study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2222–2227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.19.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nutritional anaemias: report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1968;405:5–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratz A, Lewandrowski KB. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Normal reference laboratory values. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1063–1072. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baillie FJ, Morrison AE, Fergus I. Soluble transferrin receptor: a discriminating assay for iron deficiency. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:353–357. doi: 10.1046/j.0141-9854.2003.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Lafferty MD. The Women’s Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women With Disability. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Aging; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleveland WS. Visualizing Data. Summit, NJ: Hobart Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarro JF, Mora C, Macia M, Garcia J. Randomized prospective comparison between erythropoietin and androgens in CAPD patients. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1537–1544. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cervantes F. Modern management of myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:583–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balducci L. Epidemiology of anemia in the elderly: information on diagnostic evaluation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(3 Suppl):S2–S9. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.3s.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermeulen A. Reflections concerning biochemical parameters of androgenicity. Aging Male. 2004;7:280–289. doi: 10.1080/13685530400016615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malgor LA, Valsecia M, Verges E, De Markowsky EE. Blockade of the in vitro effects of testosterone and erythropoietin on Cfu-E and Bfu-E proliferation by pre-treatment of the donor rats with cyproterone and flutamide. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Ther Latinoam. 1998;48:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leberbauer C, Boulme F, Unfried G, Huber J, Beug H, Mullner EW. Different steroids co-regulate long-term expansion versus terminal differentiation in primary human erythroid progenitors. Blood. 2005;105:85–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried W, Gurney CW. The erythropoietic-stimulating effects of androgens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;149:356–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb15169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fried W, Gurney CW. The erythropoietic response to testosterone in male and female mice. J Lab Clin Med. 1966;67:420–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rishpon-Meyerstein N, Kilbridge T, Simone J, Fried W. The effect of testosterone on erythropoietin levels in anemic patients. Blood. 1968;31:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naets JP, Wittek M. The mechanism of action of androgens on erythropoiesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;149:366–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb15170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naets JP, Wittek M. Erythropoiesis in anephric man. Lancet. 1968;1:941–943. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90901-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballal SH, Domoto DT, Polack DC, Marciulonis P, Martin KJ. Androgens potentiate the effects of erythropoietin in the treatment of anemia of end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;17:29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cesari M, Pahor M, Lauretani F, et al. Bone density and hemoglobin levels in older persons: results from the InCHIANTI study. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:691–699. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Lauretani F, et al. Hemoglobin levels and skeletal muscle: results from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:249–254. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atti AR, Palmer K, Volpato S, Zuliani G, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Anaemia increases the risk of dementia in cognitively intact elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]