Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: epistaxis and hemoptysis (original) (raw)

A 51-year-old woman with a 30-year history of recurrent epistaxis presented to the emergency department with a nosebleed. Her nosebleeds were initially mild but had gradually progressed in severity and frequency, and she had been admitted to hospital several times for cauterization. She also reported having very heavy menstrual periods in her 20s, for which she had had a hysterectomy at age 35.

The patient reported having first noticed red spots on the mucosa of her lips, oral cavity and nose in her 30s. At the same time, she began having hemoptysis. Blood transfusions had been required because of substantial bleeding. The patient had a partial right lower lobectomy and a partial lingular resection because of massive pulmonary hemorrhage. Her mother and sister both had facial telangiectasias and recurrent nosebleeds.

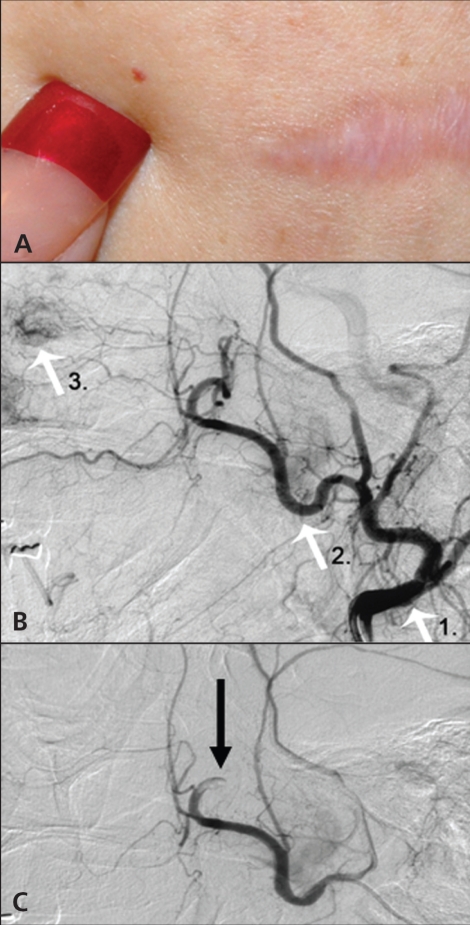

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia was diagnosed based on the Curaçao criteria,1 which include recurrent epistaxis, multiple facial telangiectasias (Figure 1A), visceral bleeding and having first-degree relatives with the same conditions.

Figure 1.

(A) Cutaneous telangiectasias on the patient’s chest. The scar is from a lung resection. (B) Angiography showing telangiectasias involving the nasal septum mucosa and its supplying arteries. White arrows point to the external carotid artery (1), the maxillary artery (2) and septal telangiectasias (3). (C) Nasal septal telangiectasias successfully treated by coil embolism. The arrow points to the coil position.

Angiography showed telangiectasias involving the nasal mucosa and its supplying arteries (Figure 1B) and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. These vascular lesions were successfully treated by coil embolization (Figure 1C ).

Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging and an abdominal computed tomography scan ruled out other arteriovenous malformations and telangiectasias. Her annual physical examination now includes careful inspection for new telangiectasias, a complete blood count to identify anemia and examination of a stool sample to identify occult blood. Her long-term follow-up plan includes a chest computed tomography scan every 5 years to detect new pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. A subsequent nosebleed was controlled by cauterization, and her hemoptysis has not recurred. The patient’s mother and sister do not have arteriovenous malformations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Betsy Toole and Anne Kemp, Media Services, St. Luke’s Hospital, Bethlehem, USA.

Footnotes

See primer by Grand’Maison, page 833, case by Manawadu and colleagues, page 836, and clinical image by Irani and Kasmani, page 839

REFERENCES

- 1.Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu–Osler–Weber syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:66–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<66::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]