Mutational Analysis of the Bunyamwera Orthobunyavirus Nucleocapsid Protein Gene (original) (raw)

Abstract

The bunyavirus nucleocapsid protein, N, is a multifunctional protein that encapsidates each of the three negative-sense genome segments to form ribonucleoprotein complexes that are the functional templates for viral transcription and replication. In addition, N protein molecules interact with themselves to form oligomers, with the viral L (RNA polymerase) protein, with the carboxy-terminal regions of either or both of the virion glycoproteins, and probably also with host cell proteins. Bunyamwera virus (BUNV), the prototype bunyavirus, encodes an N protein of 233 amino acids in length. To learn more about the roles of individual amino acids in the different interactions of N, we performed a wide-scale mutagenic analysis of the protein, and 110 single-point mutants were obtained. When the mutants were employed in a minireplicon assay to examine their effects on viral RNA synthesis, a wide range of activities compared to those of wild-type N protein were observed; changes at nine amino acid positions resulted in severely impaired RNA synthesis. Seventy-seven mutant clones were selected for use in the bunyavirus reverse genetics system, and 57 viable recombinant viruses were recovered. The recombinant viruses displayed a range of plaque sizes and titers in cell culture (from approximately 103 to 108 PFU/ml), and a number of viruses were shown to be temperature sensitive. Different assays were applied to determine why 20 mutant N proteins could not be recovered into infectious virus. Based on these results, a preliminary domain map of the BUNV N protein is proposed.

The template for both transcription and replication by negative-strand RNA viruses is not naked RNA but rather RNA encapsidated by the viral nucleocapsid (N) protein (or nucleoprotein) in the form of ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs). Both genomic (negative-sense) and antigenomic (positive-sense, also known as viral complementary or replicative intermediate) RNAs are found only in the form of RNP, indicating that encapsidation of the nascent RNA is cotranscriptional. In contrast, viral mRNAs are not encapsidated by N protein to allow ribosomal access for protein translation (10). The N protein is also suggested to play a part in regulating the switch from transcription to replication activities of the viral polymerase. Viral N proteins make many interactions: with their cognate viral RNA, with themselves to form multimers, with their cognate viral polymerase, with other viral proteins such as matrix and/or glycoproteins, and presumably with cellular proteins during the course of the replication cycle (discussed in references 10 and 22). Mapping domains or individual amino acid residues within viral N proteins responsible for these interactions is therefore necessary to facilitate an understanding of the role of N in the different facets of viral replication.

The Bunyaviridae are the largest family of negative-strand viruses, containing more than 350 named members. Bunyaviruses are characterized by a tripartite RNA genome. The family is divided into five genera (Orthobunyavirus, Hantavirus, Nairovirus, Plebovirus and Tospovirus), the members of which are distinguished by biochemical and serological criteria. All viruses share the same four structural proteins, L (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), Gn and Gc (envelope glycoproteins), and N. The N protein varies in size from about 25 kDa (orthobunyaviruses) to 50 kDa (hantaviruses and nairoviruses) (9, 12, 28, 34).

Bunyamwera virus (BUNV) is the prototype of both the Orthobunyavirus genus and the family as a whole, and its N protein is 233 amino acids (aa) in length. The BUNV N protein forms multimers in infected cells, and chemical cross-linking studies of deletion mutants indicated that both N- and C-terminal amino acids are involved in self-interaction, suggesting that head-to-head and head-to-tail interactions occur (20). BUNV N has a preference for binding to the 5′ end of genomic RNA (30), and the N protein of Jamestown Canyon orthobunyavirus shows a similar preference (29), though no mapping of the interacting domain(s) within N has been reported.

Orthobunyaviruses can be subdivided into 18 serogroups on the basis of serological relatedness of complement-fixing antibodies (mediated by the N protein) and hemagglutinating and neutralizing antibodies (mediated by the glycoproteins) (7). The N protein sequences of 51 viruses in the Bunyamwera, California, group C, and Simbu serogroups have been reported, and the sequences can be readily aligned (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). N proteins of viruses within a serogroup are the same length (233, 234, or 235 residues) and display high conservation of amino acids. When the strict criterion of absolute identity is applied across the 51 viruses, 46 positions are conserved, while a further 14 are conserved in at least 45 (90%) of the N protein sequences (Fig. 1). These residues are presumably critical for N protein function.

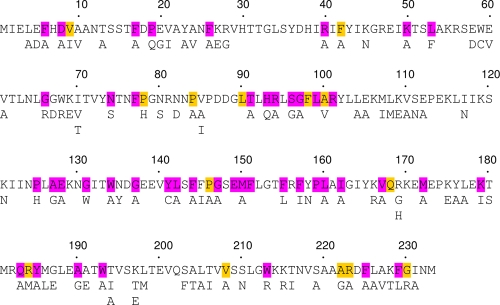

FIG. 1.

Amino acids targeted for mutagenesis in the Bunyamwera virus N protein. The sequence of the BUNV N protein is shown with the 46 residues conserved between 51 viruses in the Bunyamwera, California, group C, and Simbu serogroups highlighted in purple, while residues conserved in >90% of the viruses are shown in yellow. Below are shown the individual amino acid substitutions made.

To provide more information about the structure-function relationships of the BUNV N protein, we undertook a mutagenic study and made single-amino-acid substitutions at 110 positions. The mutant N proteins were expressed in the BUNV minireplicon system (41) to assess their activity in viral RNA synthesis. Fifty-seven recombinant viruses were recovered from selected clones by a reverse genetics procedure (25), and their phenotypes were investigated. Four temperature-sensitive viruses were characterized with respect to their defects in viral RNA synthesis. Twenty mutant N genes failed to generate infectious virus, and various assays were employed to investigate the cause. Based on these results, a preliminary domain map of the N protein is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero E6 (ATCC C1008), BHK-21, and BSR-T7/5 (6) cells were maintained as described previously (35). Working stocks of wild-type (wt) and recombinant BUNV were grown in BHK-21 cells, and titers were determined by plaque assay as detailed before (40). Recombinant vaccinia virus vTF7-3, which expresses T7 RNA polymerase (13), was propagated as described previously (17).

Plasmids and mutagenesis.

Plasmids that generate full-length antigenomic RNA transcripts [pT7riboBUNL(+), pT7riboBUNM(+), and pT7riboBUNN(+)] or express BUNV proteins under the control of an internal ribosome entry sequence (pTM1-BUNL, pTM1-BUNM, and pTM1-BUNN) have been described previously (4, 5), as have the BUNV-derived minireplicon-expressing construct, pT7riboBUNMREN(−), which contains the Renilla luciferase gene in the negative sense, and the control plasmid pTM1-FF-Luc, which expresses firefly luciferase (42).

Mutagenesis of the N open reading frame (ORF) was achieved in either a random or a specific manner using pT7riboBUNN(+) DNA as template. For random mutagenesis, the GeneMorph II kit (Stratagene) was used according to the manufacturer's directions for low-frequency mutation with modifications. pT7riboBUNN(+) DNA was linearized by digestion with HindIII, and 100 ng was amplified using 30 PCR cycles (95°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final 10-min extension at 72°C) in a 50-μl reaction mixture volume containing 125 ng each of primers Fw (GACCATGATTACGAATTC; complementary to a sequence just upstream of the T7 promoter in the plasmid) and Rv (CGATTAAAAATGCATCCC; representing bases 791 to 808 of the BUNV S segment, downstream of the N stop codon). The primers contain EcoRI and NsiI restriction enzyme sites (underlined) to facilitate cloning of the PCR product DNA into pT7riboBUNN(+) digested with the same enzymes. This approach minimized introduction of mutations into the 3′ noncoding sequence of the BUNV S segment. The inserts were subjected to nucleotide sequencing to confirm the presence of mutations. For specific site-directed mutagenesis, the QuikChange system (Stratagene) was employed, using two oligonucleotides per mutation site as detailed previously (36, 37). Primer sequences are available from the authors on request.

BUNV minireplicon assay.

The BUNV minireplicon assay was performed as previously described (18, 42) with minor modifications. Briefly, BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.2 μg each of pT7riboBUNL(+), pT7riboBUNN(+) or one of the mutated N clones, and the minireplicon plasmid pT7riboBUNMREN(−) and 0.1 μg pTM1-FF-Luc (internal transfection control). At 24 h posttransfection, Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were measured using the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Minireplicon packaging assay.

Packaging of the minireplicon RNA into viruslike particles (VLPs) basically followed the protocol described by Shi et al. (38) with modifications: BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with five plasmids, pT7riboBUNL(+) (0.2 μg), pT7riboBUNM(+) (0.1 μg), pT7riboBUNN(+) or mutant N clone (0.2 μg), pT7riboBUNMREN(−) (0.2 μg), and pTM1-FF-Luc (0.1 μg) as internal control. At 24 h posttransfection, Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were measured in cell lysates. The supernatant, containing VLPs, was used to infect monolayers of BHK-21 cells, and Renilla luciferase activity was measured after 24 h of incubation.

Metabolic radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation.

Metabolic radiolabeling and immunoprecipitation of BUNV proteins were performed as described previously (20, 35). Briefly, infected or plasmid-transfected cells, grown in 35-mm-diameter dishes, were labeled with [35S]methionine (40 μCi/ml; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and lysed on ice with 300 μl of nondenaturing RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche). BUNV proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-N antibodies that had been conjugated to protein A-agarose (Sigma). The beads were washed with RIPA buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the bound proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions.

Chemical cross-linking of N protein.

Subconfluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells grown in 35-mm dishes were infected with vaccinia virus vTF7-3 (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1) for 1 h at 37°C. The virus was then removed, and cells were transfected with 2 μg of pT7riboBUNN or mutant N clone. The following day, the cells were washed once with 0.5 ml PBS and treated with 200 μl of PBS containing 1 mM dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP; Pierce) cross-linking agent for 20 min as described previously (20). The samples were then incubated for 5 min at room temperature before 5 μl 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was added to stop the reaction. Cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-BUNV N antibodies as described previously (20).

Analysis of viral RNA.

Total RNA was extracted from Vero E6 cells infected with mutant viruses or from BSR-T7/5 cells transfected with plasmids according to the virus rescue protocol (see below) and then fractionated by agarose electrophoresis using TAE buffer (26). Following transfer to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche), viral RNAs were detected by strand-specific hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes as previously described (23).

Virus rescue by reverse genetics.

Rescue experiments were performed as described previously (25). Briefly, BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with a mixture of three plasmids, 1.0 μg each of pT7riboBUNL(+), pT7riboBUNM(+), and either pT7riboBUNN(+) or one of the pT7riboBUNN(+)-derived mutants. At 6 h posttransfection, cells were supplemented with 4 ml of growth medium and incubation continued for (usually) 5 days. Transfectant viruses were isolated by plaque formation on Vero E6 cells.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of the BUNV N ORF.

The BUNV S segment encodes two proteins, N and a nonstructural protein termed NSs, in overlapping reading frames; these proteins are translated from the same mRNA as a result of alternate AUG initiation codon usage (11). Previously, we showed that NSs was not essential for virus growth in tissue culture but that viruses lacking NSs were attenuated in cells having a competent interferon system (5, 15, 39, 41). In order to assess the effects of mutations on the functions of N protein, we used the NSs-deleted version of the S segment (5) for these studies. This approach would ensure that any phenotypic differences observed could be ascribed to N protein itself rather than the overlapping NSs protein.

Our aim was to produce a panel of N protein mutants across the entire protein covering both strictly conserved and less conserved amino acids. Using the random mutagenesis protocol (as described in Materials and Methods), 72 single-amino-acid-changing mutations in the N protein ORF were obtained out of 328 individual plasmid clones that were sequenced. A further 43 positions were mutated to alanine or glycine by the specific mutagenesis protocol. Of the 115 mutants obtained, 110 were at unique positions; 40 occurred at globally conserved sites, 14 occurred at residues conserved among at least 40 orthobunyaviruses, 11 occurred at residues conserved among at least 30 viruses, 15 occurred at positions conserved among at least 20 viruses, and 30 mutations were at nonconserved residues (Fig. 1; Table 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic analyses of Bunyamwera virus N protein mutants

Activity of mutant N proteins in the BUNV minireplicon system.

Previously, we described a minireplicon system that is dependent on transiently expressed BUNV L and N proteins to transcribe (and replicate) a BUNV-like RNA that expresses Renilla luciferase (42). The mutant N protein-expressing plasmids were introduced into this system, and their activities were compared to that of wt N protein. As summarized in Table 1, the N protein mutants showed a range of activities, from activities similar to, or even higher than, that of wt N protein to almost no activity. Seventy-nine mutants showed activity of >70% that of wt BUNV N, and interestingly, half of these had amino acid changes at globally conserved residues (shown as ++++ in Table 1). Of the nine mutants displaying <10% of wt BUNV activity, eight had substitutions at globally conserved amino acids (R94A, W134A, Y141C, L160A, K179I, Y185A, W193A, and F225A) and one (L177A) had a substitution at a leucine residue conserved among Bunymawera, California, and group C viruses that is a methionine in Aino serogroup viruses. In addition, mutation of residue 118 (I118N), which is A, F, I, M, or V in the different N proteins, resulted in a mutant N protein showing only 11% of wt BUNV activity.

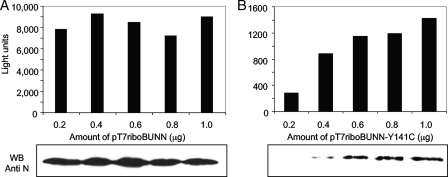

The minireplicon experiments were performed using the standard conditions optimized for use with wt protein-expressing plasmids, i.e., 0.2 μg of each plasmid (Materials and Methods). To investigate whether increasing the amount of mutant N protein-expressing plasmid might have an effect, a titration of the plasmid encoding mutant Y141C was carried out; this mutant showed 2% activity under the standard conditions. The amounts of BUNV L and minireplicon-expressing plasmids were kept constant at 0.2 μg, whereas the N protein-expressing plasmid was varied from 0.2 to 1.0 μg per dish. There was little variation in minireplicon activity or level of N protein expressed with wt BUNV N plasmid over this range (Fig. 2A). In contrast, increasing the amount of Y141C plasmid resulted in increased minireplicon activity, and this correlated with an increase in N protein as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). However, even with fivefold-more N protein-expressing plasmid in the system, the activity of Y141C was still only about 15% of that of wt BUNV N protein and the amount of N protein detected reached a plateau at a lower level than that of wt N protein. Hence, some of the low minireplicon activities shown by the mutant clones could be due to lower protein expression levels and/or poor stability of the protein, but this has not been investigated systematically.

FIG. 2.

Effect of changing the amount of BUNV N protein-expressing plasmid in the minireplicon assay. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNL, 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNMREN(−), and various amounts of pT7riboBUNN (A) or pT7riboBUNN Y141C (B) plasmid as indicated. The graphs show Renilla luciferase activity as a measure of minireplicon activity. Below are Western blots of aliquots of the same cell lysates probed with anti-BUNV antibodies to show relative N protein expression levels.

Rescue of mutant N proteins into recombinant viruses.

We previously reported a reverse genetics system to recover infectious BUNV from transfected pT7ribo-derived plasmids expressing full-length positive-sense, L, M, and S segment cDNAs without the need for helper plasmids expressing viral proteins (25). It appeared that, although they were neither capped nor polyadenylated, the cytoplasmically transcribed positive-sense RNAs could act as mRNAs for viral protein translation and also as templates for RNP formation and RNA replication (25). The system was subsequently adopted to rescue La Crosse orthobunyavirus (3) and Rift Valley fever phlebovirus (1, 2, 14, 16). Hence, the above-described pT7ribo-based plasmids expressing mutant BUNV N proteins could be used directly in attempts to recover infectious viruses. Therefore, 77 mutant N protein clones that covered the full range of activity in the minireplicon system were selected for use in the virus rescue protocol; 74 of these contained mutations at conserved residues, and three contained mutations at nonconserved amino acids (Table 1). Fifty-seven recombinant viruses were rescued (Table 1), whereas 20 mutant N genes were repeatedly (in at least three attempts) nonrescuable (shown in purple in Table 1). This suggests that these residues (F17, F26, R94, I118, P125, G131, W134, Y141, F144, Y158, L160, Y176, L177, K179, Y185, W193, W213, F225, L226, and I231) are critical at some stage in the virus life cycle.

The efficiency of recovery of the mutant viruses, as estimated by the dilution of supernatant of the transfected cell from which plaques could be picked, varied greatly. Some mutants were recovered at the same efficiency as was rBUNdelNSs (i.e., plaques obtained from a 10−7 dilution, e.g., V85A), whereas others were recovered only from undiluted supernatant (K50A, G66R, and W68R). On two occasions, plaques were recovered at low yield from cells transfected with N mutants G137A and F157I after prolonged incubation (>12 days); in both instances, sequence analysis of the S segment of the recovered virus showed that the sequence was the same as that of the wt N gene, suggesting that reversion had occurred.

An individual plaque isolate of each recombinant virus was grown up, and the complete sequence of the S segment was verified following reverse transcription-PCR amplification. The majority of recombinant viruses carried only the input mutation in the N protein. Five mutant viruses were found to carry the input mutation plus a second mutation, and two viruses contained two additional mutations (Table 2). Notably, the additional mutation in recombinant viruses D8A, E20G, and W68R occurred at the same nonconserved residue and resulted in the same substitution, K109E. The significance of these additional amino acid substitutions requires further investigation. In none of the recombinant viruses was the NSs ORF recreated.

TABLE 2.

Additional mutations in the N proteins of seven recombinant viruses

| Recombinant virus | Input mutation | Additional mutation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| D8A | D8A | K109E |

| E20G | E20G | K109E |

| R40A | R40A | T71S |

| G66R | G66R | R28H |

| W68R | W68R | K109E |

| E112A | E112A | K27E, T62A |

| R184M | R184M | D8G, F97S |

Characterization of mutant viruses.

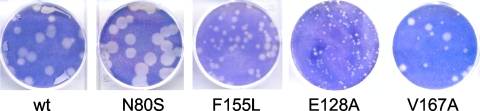

There are a number of ways in which the mutant viruses could be classified. Here we have grouped them according to their degree of attenuation in Vero E6 cells at 33°C. Hence, viruses in group 1 (40 viruses, shown in yellow in Table 1) grew to within 2 log units of rBUNdelNSs, which encodes wt N protein; mutants in group 2 (11 mutants, shown in blue) were moderately attenuated and grew 2 to 4 log units lower than did rBUNdelNSs; and mutants in group 3 (five mutants, A100V, G147A, M150A, 162A, and V208A, shown in green) were severely attenuated and gave yields more than 4 log units lower than that of rBUNdelNSs. At 33°C, three size classes of plaque on Vero E6 cells could be distinguished: large, 4 to 5 mm in diameter, as produced by rBUNdelNSs; medium, approximately 2 mm in diameter; and small, about 1 mm in diameter (Fig. 3; Table 1). A few recombinant viruses produced plaques of mixed sizes. There was no correlation between plaque size and degree of attenuation: for instance, some mutants in group 1 (e.g., E128A) gave small plaques while the severely attenuated mutant A100V produced large plaques.

FIG. 3.

Plaque phenotypes of recombinant BUNV expressing mutant N proteins. Vero E6 cells were infected with the different viruses and incubated at 33°C for 6 days. Cells were then fixed with 5% formaldehyde and stained with Giemsa stain. Examples are shown of large (N80S), medium (F155L), small (E128A), and mixed (V167A) plaques.

The rescue of mutant viruses was performed at 33°C to increase the probability of recovering viruses that grew less well at higher temperatures. The titers of stocks of the different mutants were compared by plaque assay in Vero E6 cells at 33°C, 37°C, and 38°C. BUNdelNSs virus behaved similarly at the three temperatures, producing similar-sized plaques and only a 0.2-log-unit difference in titer (Table 1); the efficiency of plating (EOP; calculated as titer at 38°C/titer at 33°C) was therefore 0.5. The majority of N mutant viruses showed up to a 10-fold drop in titer at higher temperatures and EOP values of 0.1 to 0.3, whereas some showed much larger decreases in titer and had EOP values of less than 0.01. Three mutant viruses (F6A, G147A, and V208A) grew poorly at 33°C, giving small plaques and low titers (103 to 104 PFU/ml), and did not form plaques at 37°C or 38°C. Four other viruses (L104A, M150A, I162A, and M172A) formed plaques only at 33°C and 37°C.

Based on these observations, a number of mutants could be considered temperature sensitive. We selected four mutants (N74S, S96G, K228T, and G230R) that grew to high titers at 33°C (and formed large plaques) and had an EOP of <0.009 for further characterization. K228T and G230R produced small plaques at 38°C but normal-sized plaques at 37°C, whereas the plaque size of N74S and G96S was only slightly affected at higher temperatures. Although mutant viruses F6A, K50A, L104A, G147A, M150A, I162A, M172A, and V208A all showed EOPs of <0.008, they grew to low titers at 33°C and thus would be more difficult to study.

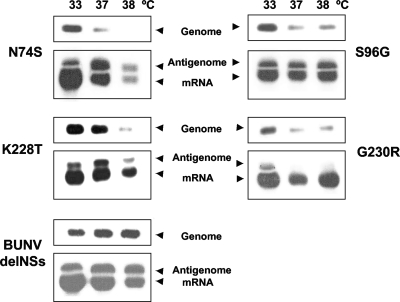

Characterization of temperature-sensitive viruses.

The RNA synthesis phenotypes of the four selected viruses were analyzed at the different temperatures by Northern blotting. Strand-specific hybridization probes can be used to distinguish genome and antigenome RNAs, but only S segment mRNA is sufficiently different in size from antigenome RNA to be resolved by gel electrophoresis (24). Therefore, analysis of the S segment RNA species was undertaken on total RNA extracted from infected Vero E6 cells (16 h postinfection, MOI of 1; Fig. 4). No difference in intensity of the signal for S genome RNA was seen for rBUNdelNSs virus at the different temperatures. The S mRNA signal was slightly greater at 33°C than at the higher temperatures, but the antigenome signals were similar. For mutant virus N74S, there was a loss of S genome signal at higher temperatures and an overall decrease in signal for both antigenome and mRNA at 38°C. Mutant S96G also showed a decrease in genome RNA at higher temperatures, but no difference was observed for either positive-sense RNA species. Therefore, these mutants, which have amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal third of the N protein, have a temperature-sensitive defect in genome replication. Mutant K228T showed a decrease in signal of both genome and antigenome at 38°C but not of mRNA. Similarly, mRNA production was not affected by increasing temperature in mutant G230R-infected cells, whereas genome and antigenome synthesis was decreased at both 37°C and 38°C. Therefore, these mutants, which have mutations near the C terminus of the N protein, have a defect in antigenome synthesis, and G230R is more temperature sensitive.

FIG. 4.

RNA analysis of recombinant BUNV expressing mutant N proteins. Vero E6 cells (three dishes per virus) were infected with rBUNdelNSs or mutant viruses at an MOI of 1 and incubated overnight at 33°C, 37°C, or 38°C. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent and separated on 1.2% agarose gels, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were hybridized with strand-specific digoxigenin-labeled probes to detect S segment genomic RNA or S segment antigenomic RNA and mRNA as indicated.

Characterization of nonrescuable N protein genes.

Twenty mutant N genes carrying single-point mutations were unable to generate plaque-forming infectious virus (Table 1). Assays were developed to investigate which function of the different mutants that might have prevented infectious virus production was disrupted. Experimental data are shown for representative mutants in the different assays; full results are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Summary of nonrescuable mutant N proteins

| N mutant | Minigenome activity (%)a | Genomic RNA synthesisb | N-L interaction (%)c | Ability to form multimersd | Minireplicon packaging activity (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F17A | 12 | − | NTf | NT | NT |

| F26A | 30 | + | NT | NT | NT |

| R94A | <1 | − | 90 | − | − |

| I118N | 11 | + | 63 | − | − |

| P125H | 66 | + | NT | + | 29 |

| G131W | 40 | + | NT | + | 42 |

| W134A | 2 | − | 48 | − | − |

| Y141C | 2 | − | 36 | − | − |

| F144A | 29 | + | NT | NT | NT |

| Y158N | 30 | + | NT | + | 12 |

| L160A | 3 | − | NT | NT | NT |

| Y176A | 53 | + | NT | + | 36 |

| L177A | 10 | − | NT | − | − |

| K179I | 4 | − | 91 | − | − |

| Y185A | <1 | − | NT | NT | NT |

| W193A | 3 | − | 96 | + | − |

| W213R | 28 | + | NT | + | 12 |

| F225A | <1 | − | NT | NT | NT |

| L226A | 26 | + | NT | + | 66 |

| I231A | 95 | + | NT | + | 12 |

RNA synthesis.

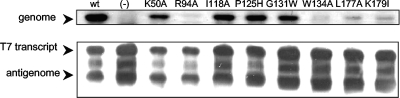

The nonrescuable mutant N genes showed a range of activities in the minireplicon experiments, ranging from essentially no activity to wt levels (Table 1). This assay measures the result of encapsidation of the minireplicon RNA by N protein, followed by both replication and transcription of the RNA (25, 42), and thus, mutations in N could have effects at a number of stages. To investigate whether mutant N proteins had a defect in their ability to support genomic RNA synthesis, Northern blot analysis was performed on transfected cells. In the BUNV rescue system, the pT7riboBUNN, -M, and -L constructs are transcribed by the T7 polymerase to produce positive-sense RNA transcripts. The transcripts contain a hepatitis δ virus ribozyme sequence which promotes self-cleavage to produce the full-length antigenomic viral RNAs. The latter are encapsidated by the N protein and are used as templates to produce full-length genomic RNAs. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.2 μg each of pT7riboBUNN or mutant N clone, pT7riboBUNM, and pT7riboBUNL DNA as described in Materials and Methods, and after 16 h of incubation at 33°C, total RNA was extracted. Duplicate RNA blots were hybridized with positive- or negative-sense probes (Fig. 5.).

FIG. 5.

RNA synthesis by nonrescuable mutant N proteins. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNN(+) or mutant N protein-expressing plasmid, 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNM(+), and 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNL(+). After overnight incubation at 33°C, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent and separated on 1.2% agarose gels, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were hybridized with strand-specific digoxigenin-labeled probes to detect BUNV S segment genomic RNA or S segment antigenomic RNA. The unprocessed positive-sense RNA transcribed from the transfected plasmid is designated T7 transcript.

All constructs produced both the unprocessed T7 transcript and the processed antigenome RNA. An additional RNA species was detected in all samples by the negative-sense probe between the unprocessed transcript and the full-length antigenomic RNA; the origin of this band is unknown (Fig. 5). No authentic BUNV mRNA species was detected in the cells at this relatively early time posttransfection; mRNA would have to be transcribed from viral RNA, and this would occur later once virus-polymerase-driven replication was under way. When hybridized with the positive-sense probe, S segment genome RNA was detected in cells transfected with wt constructs. Detection of this RNA was dependent on the coexpressed BUNV L protein, as no signal was evident in the negative-control sample in which the BUNV L protein-expressing plasmid was omitted. Mutant K50A, which was rescued into virus, was included as another positive control and showed a pattern similar to that of wt N. Of the tested nonrescuable N mutants shown, I118N, P125H, and G131W supported RNA synthesis, whereas R94A, W134A, L177A, and K179I were impaired in their ability to replicate the S segment. In fact, all nonrescuable mutant N proteins that gave low activity in the minireplicon assay were defective in their ability to support genomic RNA synthesis (Table 3).

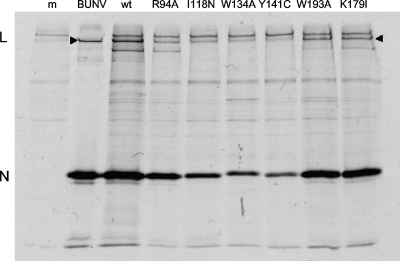

N-L interaction.

To examine whether there was a defect in interaction of mutant N proteins with L protein, a coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed. BSR-T7/5 cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing BUNV L and N proteins (pTM1-derived constructs were used to increase expression levels as the target gene is under the control of an internal ribosome entry sequence), and then radiolabeled cell lysates were reacted with a monospecific anti-N antibody. As can be seen in Fig. 6, the L protein was coprecipitated with N protein both in virus-infected cells and in cells cotransfected with plasmids expressing wt proteins. Note that there is a band above the L protein that is derived from BSR-T7/5 cells (also seen in mock-transfected cells) that is not seen in the BUNV-infected Vero E6 cell marker track. Mutant N proteins W193A and K179I also clearly interacted with L protein. Mutants R94A, I118N, W134A, and Y141C were expressed at lower levels than was wt N, and hence, less L protein was coprecipitated. Therefore, densitometry was used to estimate the relative amounts of N and L protein bands and to normalize the amount of L with respect to N. While the amount of L coprecipitated with R94A was similar to that observed with wt N, less L was coprecipitated with the other mutants (from 36 to 63%; Table 3).

FIG. 6.

Interaction of BUNV L protein with mutant N proteins. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with 0.1 μg pTM1-BUNN or mutant N protein-expressing plasmid (as indicated), 0.1 μg of pTM1-BUNL, and 0.2 μg of pT7riboBUNMREN(−) or left untransfected (m) and were incubated overnight at 33°C. The culture medium was then replaced with methionine-deficient medium containing 40 μCi/ml [35S] methionine, and incubation continued for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and reacted with anti-BUNV N protein antibodies, and immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The positions of BUNV L and N proteins are shown. Immunoprecipitated proteins from BUNV-infected Vero E6 cells (BUNV) were used as markers. The band above L is a protein derived from BSR-T7/5 cells.

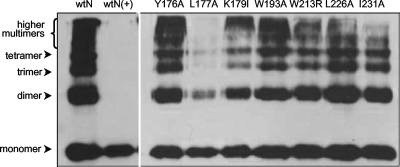

N-N interaction.

The ability of individual N molecules to form multimers was tested in a chemical cross-linking experiment as detailed previously (20), where N-N interaction was shown to be independent of the presence of RNA. Vero E6 cells were infected with vaccinia virus vTF7-3 to express T7 RNA polymerase and then transfected with the different plasmids. The cells were treated with 1 mM DSP, a cross-linking agent that creates a disulfide bridge between two reactive primary amines. As the bridge contains thiol-thiol interactions, it can be broken by the addition of β-mercaptoethanol to loading buffer. As shown in Fig. 7, wt BUNV N protein produced a ladder of protein bands, characterized as monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers, and higher multimers toward the top of the gel, with molecular masses corresponding to multiples of 25 kDa, as described previously (20). Treatment with β-mercaptoethanol, in the lane labeled wtN(+), destroyed the cross-linked multimers. Of the tested mutant N proteins shown, L177A was deficient in its ability to form multimers and K179I appeared compromised in its ability to form trimers and higher multimers. These mutants showed relatively low activity (10% and 4%, respectively) in the minireplicon assay. The other examples shown in the figure appeared not to be affected in multimerization. Interestingly, W193A showed only 3% activity in the minireplicon assay, whereas all the other mutants that formed multimers showed at least moderate activity in the minireplicon experiments.

FIG. 7.

Cross-linking of nonrescuable mutant N proteins. Vero E6 cells were infected with recombinant vaccinia virus vTF7-3 (which expresses T7 RNA polymerase) and transfected with 2 μg pT7riboBUNN or mutant N protein-expressing plasmid as indicated. N proteins were cross-linked using 1 mM DSP, and the samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-BUNV antibodies. The positions of BUNV N protein and its multimers are indicated. β-Mercaptoethanol was added to the protein loading buffer to destroy cross-links in the lane labeled wtN(+).

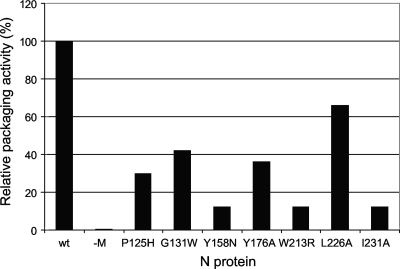

Minireplicon packaging.

A BUNV minireplicon packaging assay was described previously, in which VLPs were produced in cells transfected with plasmids that express BUNV proteins and the Renilla luciferase-containing minireplicon. The VLPs could be used to infect new cells, expressing BUNV N and L proteins either by BUNV infection or by prior transfection with appropriate expression plasmids, resulting in passage of Renilla activity (19, 38). Further development of the system showed first that there was no need to express N and L protein in the cells to be infected with VLPs and second that by use of pT7ribo-based plasmids infectious virus carrying the Renilla minireplicon could also be produced (data not shown). Thus, BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with three pT7ribo-based plasmids encoding L, M, and N viral proteins; the BUNV minireplicon plasmid; and pT7-FF-Luc as an internal transfection control. After 24 h of incubation at 33°C, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. The culture medium was cleared of cellular debris and used to infect naive BHK-21 cells, which were incubated overnight at 33°C and then assayed for Renilla luciferase activity.

Only the mutant N proteins that were functional in the BUNV minireplicon system (P125H, G131W, Y158N, Y176A, W213R, L226A, and I231A) were used to test their ability to form infectious VLPs. Packaging activity of the wt N protein (determined by measuring passaged Renilla luciferase activity relative to normalized minireplicon activity) was taken as 100%; omission of the M-segment plasmid, expressing the viral glycoproteins and NSm protein, did not produce infectious virus and hence no Renilla luciferase activity (Fig. 8). Packaging activity of the mutants was calculated similarly and expressed as a percentage of that of wt N. Mutant N proteins Y158N, W213R, and I231A were all impaired in packaging, showing only about 12% activity compared to wt N protein. Mutant N proteins P125H, G131W, Y176A, and L226A displayed higher packaging activities of 29%, 42%, 36%, and 66%, respectively.

FIG. 8.

BUNV minireplicon packaging activity. BSR-T7/5 cells were transfected with five plasmids, 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNL(+), 0.1 μg pT7riboBUNM(+), 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNN(+) or mutant N protein-expressing plasmid as indicated, 0.2 μg pT7riboBUNMREN(−) (which expresses the minireplicon), and 0.1 μg pTM1-FF-Luc as internal control. As negative control, pT7riboBUNM(+) was omitted and replaced with empty vector (−M). After incubation for 5 h at 37°C, the transfection mixtures were removed and replaced with fresh medium, and incubation continued overnight at 33°C. The supernatants were then collected, clarified by centrifugation, and transferred to monolayers of BHK-21 cells. After incubation for a further 24 h, luciferase assays were performed on cell lysates. Transferred Renilla luciferase activity was taken as a measure of packaging activity and was normalized with respect to minireplicon activity measured in the initially transfected cells. Packaging activity with wt protein-expressing plasmids was taken as 100%.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the importance of both conserved and nonconserved amino acids in the orthobunyavirus N protein in the viral life cycle. Previously, we demonstrated by analysis of deletion mutants that the N-terminal 10 residues and the C-terminal 17 residues of the prototypic BUNV N protein are important for N molecule multimerization (20). Here we applied wide-scale mutagenic analyses to examine single substitutions of other residues, both residues that were globally conserved among 51 orthobunyaviruses (and hence more likely to be of functional significance) and nonconserved residues that could act as internal controls (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As the BUNV S segment encodes N and NSs in overlapping reading frames, we used an NSs-deleted form of the cDNA as template. This would allow the phenotypes of mutants to be ascribed to the mutation in N protein alone, though it has the disadvantage that any mutant viruses created would not express NSs and hence would be attenuated in interferon-competent cells (41). Ideally, we would have preferred to express the NSs protein from an independent cistron, but so far this has not proved possible. As there was a lack of any information on the domain structure of BUNV N protein, we chose a random mutagenesis approach to make many single substitutions across the N ORF in a time- and cost-effective manner, followed by site-directed mutagenesis to target particular residues. We consider this strategy to have been moderately successful, in that we obtained 72 single-point mutants by the random approach (representing substitution at 30% of the N protein residues) from 328 plasmids sequenced. Forty-three conserved positions were then changed to alanine or glycine by the site-directed protocol. By creating mutations in pT7riboBUNN(+), both minireplicon activity and virus rescue could be investigated from the same plasmid.

The BUNV minireplicon system was exploited to assay the effects of the point mutations in the N protein on RNA synthesis. Others have applied analogous minireplicon systems to investigate mutations in influenza A virus and vesicular stomatitis virus N proteins (21, 27). However, it should be noted that this assay measures the result of (i) N-RNA interaction to assemble the RNP, (ii) recognition of the RNP by L protein, (iii) transcription (and probably replication [8, 42]) of the minireplicon, and (iv) translation of mRNA to yield measurable reporter activity. Therefore, while the minireplicon system provides a useful starting point to analyze N protein mutants, it provides only limited information, and other functional assays are required to gain a fuller understanding of N protein function.

Both high and low activities of mutant N proteins (compared to that of the wt) in the minireplicon assay need to be interpreted with caution. For instance, while most mutants that gave high activity could be rescued into infectious virus (Table 1), a few could not (e.g., P125H and I231A), and these mutant N proteins probably have a defect in RNP packaging or virion assembly. On the other hand, some mutants might show low activity because the N protein is unstable or poorly expressed from the plasmid under standard conditions (e.g., Y141C), rather than because the mutants have a specific defect that affects a particular aspect of N′s activity. Although this could be investigated further by varying the experimental conditions of the minireplicon assay, it would, however, be very laborious to titrate optimal plasmid amounts when analyzing >100 mutants. Mutation at some globally conserved residues apparently had no effect on virus replication, e.g., N74S and S96G, while others gave rise to viruses that replicated to high titers but formed small plaques, e.g., E128A (Table 1). Conversely, mutations at some poorly conserved residues, e.g., I118N and Y176A, were apparently lethal in that infectious virus containing these amino acid substitutions could not be recovered.

The ability to create recombinant viruses expressing defined mutations is a powerful tool to investigate gene function, but careful characterization of transfectant viruses is required. Attempts to rescue mutant N proteins G137A and F157I resulted in infectious virus detection after prolonged incubation (12 days) of the transfected cells, and subsequent nucleotide sequence analysis showed that both viruses expressed N proteins of wt sequence. In addition, other transfectant viruses carried additional mutations that were not present in the plasmids used in the rescue protocol (Table 2). These data highlight the importance of sequencing the genomes of viruses recovered by reverse genetics.

Some recombinant viruses yielded plaques of mixed sizes, e.g., G67D and A222G (Table 1). Where tested, these viruses continued to show a mixed plaque phenotype after individual plaques were picked. It would be of interest to determine the error frequency of the viral polymerase in these viruses to determine whether polymerase fidelity can be influenced by mutations in the N protein; however, this is outside the scope of the present work.

The characterization of four temperature-sensitive mutations in the N protein is noteworthy, as previously only a single orthobunyavirus temperature-sensitive mutant mapping to the S genome segment, from over 210 temperature-sensitive mutants reported (31), had been described, namely, Maguari virus ts23 (MAGts23) (31, 32). Maguari virus is closely related to BUNV in the Bunyamwera serogroup, and MAGts23 showed an EOP of 0.001. Analysis of the RNAs synthesized at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures by using strand-specific hybridization probes to the S segment revealed that the four BUNV mutants could be divided into two groups, those that were defective in antigenome synthesis but not mRNA transcription (K228T and G230R) and those that were replication defective but transcription competent (N74S and S96G). This suggests that distinct regions of the N protein are involved in these different RNA synthetic events. In agreement with these results, the amino acid change in the N protein of MAGts23 is a V-to-A change at residue 85, and this mutant is also defective in replication at nonpermissive temperature (unpublished results of the work of D. C. Pritlove and R. M. Elliott, quoted in reference 31). However, in this case, there is also an amino acid change at residue 16 in NSs that could have an effect. Two mutations at V85 in BUNV N were made, and two mutant viruses were recovered, V85A and V85I; neither of these mutants was as temperature sensitive as was MAGts23, showing EOPs of 0.04 and 0.2, respectively (Table 1).

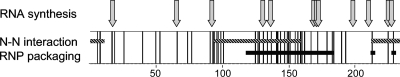

Recent mutagenic studies of conserved amino acids in the N proteins of influenza A and vesicular stomatitis viruses (21, 27) have correlated function directly to the three-dimensional structure of the respective proteins. In advance of its three-dimensional structure determination, we propose a putative linear domain map of BUNV N protein (Fig. 9) based on data from the work of Leonard et al. (20) and the information reported herein. Residues in the N-terminal region (aa 1 to 10), in the middle region (aa 94 to 158), and in the C-terminal region (aa 216 to 233) appear to be involved in N-N interactions. Residues F17, F144, L160, Y176, L177, K179, Y185, W193, W213, and F226 are involved in RNA synthesis, while amino acids P125, G131, Y158, and I231 are involved in RNP packaging. The BUNV N protein has been crystallized, and preliminary X-ray diffraction data have been obtained (33); it will be highly instructive to see how the residues identified by our functional analyses map onto the fully folded N protein once its structure is resolved.

FIG. 9.

Preliminary domain map of BUNV N protein. Vertical lines represent the positions of conserved amino acids in the BUNV N protein, and domains or individual amino acid positions that affect the indicated functions of N protein are shown.

Supplementary Material

[Supplemental material]

Acknowledgments

S.A.E. was supported by a scholarship from King Saud University, and work in the laboratory of R.M.E. was funded by grants from the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

▿

Published ahead of print on 26 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Billecocq, A., N. Gauliard, N. Le May, R. M. Elliott, R. Flick, and M. Bouloy. 2008. RNA polymerase I-mediated expression of viral RNA for the rescue of infectious virulent and avirulent Rift Valley fever viruses. Virology 378**:**377-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird, B. H., C. G. Albariño, and S. T. Nichol. 2007. Rift Valley fever virus lacking NSm proteins retains high virulence in vivo and may provide a model of human delayed onset neurologic disease. Virology 362**:**10-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakqori, G., and F. Weber. 2005. Efficient cDNA-based rescue of La Crosse bunyaviruses expressing or lacking the nonstructural protein NSs. J. Virol. 79**:**10420-10428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridgen, A., and R. M. Elliott. 1996. Rescue of a segmented negative-strand RNA virus entirely from cloned complementary DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93**:**15400-15404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridgen, A., F. Weber, J. K. Fazakerley, and R. M. Elliott. 2001. Bunyamwera bunyavirus nonstructural protein NSs is a nonessential gene product that contributes to viral pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98**:**664-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz, U. J., S. Finke, and K. K. Conzelmann. 1999. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J. Virol. 73**:**251-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calisher, C. H. 1996. History, classification and taxonomy of viruses in the family Bunyaviridae, p. 1-17. In R. M. Elliott (ed.), The Bunyaviridae. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 8.Dunn, E. F., D. C. Pritlove, H. Jin, and R. M. Elliott. 1995. Transcription of a recombinant bunyavirus RNA template by transiently expressed bunyavirus proteins. Virology 211**:**133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott, R. M. 2008. Bunyaviruses: general features, p. 390-399. In B. W. J. Mahy and M. H. V. van Regenmortel (ed.), Encyclopedia of virology, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 10.Elliott, R. M. 2005. Negative strand RNA virus replication, p. 127-134. In B. Mahy and V. ter Meulen (ed.), Topley and Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections: virology, 10th ed., vol. 1. Hodder Arnold, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott, R. M. 1989. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the small (S) RNA segment of Bunyamwera virus, the prototype of the family Bunyaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 70**:**1281-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott, R. M. (ed.). 1996. The Bunyaviridae. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 13.Fuerst, T. R., E. G. Niles, F. W. Studier, and B. Moss. 1986. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83**:**8122-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habjan, M., N. Penski, M. Spiegel, and F. Weber. 2008. T7 RNA polymerase-dependent and -independent systems for cDNA-based rescue of Rift Valley fever virus. J. Gen. Virol. 89**:**2157-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart, T. J., A. Kohl, and R. M. Elliott. 2009. Role of the NSs protein in the zoonotic capacity of Orthobunyaviruses. Zoonoses Public Health 56**:**285-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikegami, T., S. Won, C. J. Peters, and S. Makino. 2006. Rescue of infectious Rift Valley fever virus entirely from cDNA, analysis of virus lacking the NSs gene, and expression of a foreign gene. J. Virol. 80**:**2933-2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin, H., and R. M. Elliott. 1992. Mutagenesis of the L protein encoded by Bunyamwera virus and production of monospecific antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 73**:**2235-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohl, A., T. J. Hart, C. Noonan, E. Royall, L. O. Roberts, and R. M. Elliott. 2004. A Bunyamwera virus minireplicon system in mosquito cells. J. Virol. 78**:**5679-5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohl, A., A. C. Lowen, V. H. J. Leonard, and R. M. Elliott. 2006. Genetic elements regulating packaging of the Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 87**:**177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard, V. H., A. Kohl, J. C. Osborne, A. McLees, and R. M. Elliott. 2005. Homotypic interaction of Bunyamwera virus nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 79**:**13166-13172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, Z., T. Watanabe, M. Hatta, S. Watanabe, A. Nanbo, M. Ozawa, S. Kakugawa, M. Shimojima, S. Yamada, G. Neumann, and Y. Kawaoka. 2009. Mutational analysis of conserved amino acids in the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 83**:**4153-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longhi, S. 2009. Nucleocapsid structure and function. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 329**:**103-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowen, A. C., A. Boyd, J. K. Fazakerley, and R. M. Elliott. 2005. Attenuation of bunyavirus replication by rearrangement of viral coding and noncoding sequences. J. Virol. 79**:**6940-6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowen, A. C., and R. M. Elliott. 2005. Mutational analyses of the nonconserved sequences in the Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus S segment untranslated regions. J. Virol. 79**:**12861-12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowen, A. C., C. Noonan, A. McLees, and R. M. Elliott. 2004. Efficient bunyavirus rescue from cloned cDNA. Virology 330**:**493-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masek, T., V. Vopalensky, P. Suchomelova, and M. Pospisek. 2005. Denaturing RNA electrophoresis in TAE agarose gels. Anal. Biochem. 336**:**46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nayak, D., D. Panda, S. C. Das, M. Luo, and A. K. Pattnaik. 2009. Single-amino-acid alterations in a highly conserved central region of vesicular stomatitis virus N protein differentially affect the viral nucleocapsid template functions. J. Virol. 83**:**5525-5534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichol, S. T., B. J. Beaty, R. M. Elliott, R. Goldbach, A. Plyusnin, C. S. Schmaljohn, and R. B. Tesh. 2005. Bunyaviridae, p. 695-716. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 29.Ogg, M. M., and J. L. Patterson. 2007. RNA binding domain of Jamestown Canyon virus S segment RNAs. J. Virol. 81**:**13754-13760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osborne, J. C., and R. M. Elliott. 2000. RNA binding properties of Bunyamwera virus nucleocapsid protein and selective binding to an element in the 5′ terminus of the negative-sense S segment. J. Virol. 74**:**9946-9952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pringle, C. R. 1996. Genetics and genome segment reassortment, p. 189-226. In R. M. Elliott (ed.), The Bunyaviridae. Plenum Press, New York, NY.

- 32.Pringle, C. R., and C. U. Iroegbu. 1982. Mutant identifying a third recombination group in a bunyavirus. J. Virol. 42**:**873-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodgers, J. W., Q. Zhou, T. J. Green, J. N. Barr, and M. Luo. 2006. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the nucleocapsid protein of Bunyamwera virus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 62**:**361-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmaljohn, C. S., and J. W. Hooper. 2001. Bunyaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1581-1602. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 35.Shi, X., K. Brauburger, and R. M. Elliott. 2005. Role of N-linked glycans on Bunyamwera virus glycoproteins in intracellular trafficking, protein folding, and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 79**:**13725-13734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi, X., and R. M. Elliott. 2004. Analysis of N-linked glycosylation of Hantaan virus glycoproteins and the role of oligosaccharide side chains in protein folding and intracellular trafficking. J. Virol. 78**:**5414-5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi, X., and R. M. Elliott. 2002. Golgi localization of Hantaan virus glycoproteins requires coexpression of G1 and G2. Virology 300**:**31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi, X., A. Kohl, P. Li, and R. M. Elliott. 2007. Role of the cytoplasmic tail domains of Bunyamwera orthobunyavirus glycoproteins Gn and Gc in virus assembly and morphogenesis. J. Virol. 81**:**10151-10160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Streitenfeld, H., A. Boyd, J. K. Fazakerley, A. Bridgen, R. M. Elliott, and F. Weber. 2003. Activation of PKR by Bunyamwera virus is independent of the viral interferon antagonist NSs. J. Virol. 77**:**5507-5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watret, G. E., C. R. Pringle, and R. M. Elliott. 1985. Synthesis of bunyavirus-specific proteins in a continuous cell line (XTC-2) derived from Xenopus laevis. J. Gen. Virol. 66**:**473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber, F., A. Bridgen, J. K. Fazakerley, H. Streitenfeld, N. Kessler, R. E. Randall, and R. M. Elliott. 2002. Bunyamwera bunyavirus nonstructural protein NSs counteracts the induction of alpha/beta interferon. J. Virol. 76**:**7949-7955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber, F., E. F. Dunn, A. Bridgen, and R. M. Elliott. 2001. The Bunyamwera virus nonstructural protein NSs inhibits viral RNA synthesis in a minireplicon system. Virology 281**:**67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[Supplemental material]