Mouse Models of Fragile X-Associated Tremor Ataxia (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Dec 1.

Abstract

Objective

To describe the development of mouse models of Fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia (FXTAS) and the behavioral, histological and molecular characteristics of these mice.

Method

This paper compares the pathophysiology and neuropsychological features of FXTAS in humans to the major mouse models of FXTAS. Specifically, the development of a transgenic mouse line carrying an expanded CGG trinucleotide repeat in the 5′untranslated regions of the Fmr1 gene is described along with a description of the characteristic intranuclear ubiquitin positive inclusions and the behavioral sequella observed in these mice.

Results

CGG KI mice model many of the important features of FXTAS, although some aspects are not well modeled in mice. Aspects of FXTAS that are modeled well include elevated levels of Fmr1 mRNA, reduced levels of Fmrp, the presence of intranuclear inclusions that develop with age and show similar distributions within neurons, and neuropsychological and cognitive deficits, including poor motor function, impaired memory and evidence of increased anxiety. Features of FXTAS that are not well modeled in these mice include intentional tremors that are observed in some FXTAS patients but have not been reported in CGG KI mice. In addition, while intranuclear inclusions in astrocytes are very prominent in FXTAS, there are relatively few observed in CGG KI mice. A number of additional features of FXTAS have not been systematically examined in mouse models yet, including white matter disease, hyperintensities in T2-weighted MRI, and brain atrophy, although these are currently under investigation in our laboratories.

Conclusion

The available mouse model has provided valuable insights into the molecular biology and pathophysiology of FXTAS, and will be particularly useful for developing and testing new therapeutic treatments in the future.

Keywords: FXTAS, mouse models, Fmr1, Fmrp, Fragile X, ubiquitin, neurodegenerative disorder

Introduction

The Fragile X mental retardation 1 gene (FMR1) is located on the long-arm of the X-chromosome at Xq27.3 and codes for the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) which is necessary for normal brain development and synaptic plasticity1. In normal individuals the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) has sequence of between 10-55 tandem CGG trinucleotide repeats. Expansion of the repeat sequence to greater than 200 CGG's results in methylation of the adjacent CpG islands, gene silencing and an absence of FMRP. This is referred to as the full-mutation and results in Fragile X syndrome (FXS). In the Fragile X premutation, CGG repeat expansions are between 55 and 200. Premutation carriers were previously thought to be otherwise healthy, but recent evidence demonstrated that the premutation may result in the Fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia syndrome (FXTAS).1, 2 In FXTAS there is a progressive late onset tremor/ataxia, white matter disease, intranuclear ubiquitin-positive inclusions, neuropsychological problems, and in some patients brain atrophy and dementia.3

The study of FXS and FXTAS has been greatly facilitated by the development of animal models that mimic much of the pathology associated with these disorders (see Table 1).4, 5

Table 1. Comparison of FXTAS with the CGG KI Mouse.

- CGG Expansions

- Elevated FMR1 mRNA

- FMRP

- Motor Impairment

- Cognitive Impairment

- Intranuclear Ubituitin-positive Inclusions

Specifically, reverse genetics has been used to create knock-in mice carrying expanded (CGG)98 trinucleotide repeats in the 5′UTR of Fmr1 as a model of FXTAS, referred to hereafter as CGG KI mice. Knock-out (KI) mice lacking the Fmr1 gene and therefore the Fmrp protein have also been generated as a model of FXS. The focus of this review will be on the development and characterization of CGG KI mice to study FXTAS and the insights that have been gained from their study. It is notable that transgenic mouse models expressing expanded-CGG repeat tracts were available long before the discovery of FXTAS. These genetically modified mice with CGG repeat expansions were initially generated to study the CGG repeat instability that occurs in FXS, rather than to model what is now recognized as the neurodegenerative disease FXTAS.

Repeat instability

The first transgenic mouse models created expressed 81 CGGs repeat units in the human FMR1 promoter and included two interruptions (AGG and CAG) with a pure (CGG)60 tract.16 Unlike in humans where CGG repeat instability occurs, often as a dynamic expansion upon transmission to the next generation, CGG inheritance in these CGG transgenic mice was stable under all mitosis and meiosis conditions examined. Similar results were obtained in transgenic mice expressing either an interrupted (CGG)86 repeat tract or a pure (CGG)97 repeat tract in the human FMR1 promoter.17, 18 Several transgenic mouse lines carrying CGG repeats were subsequently generated using yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs). YACs allow the inclusion of large flanking sequences and other regulatory elements, and YAC transgenic mice expressing CGG repeats of varying lengths show CGG expansion-dependent intergenerational instability, although only small expansions and contractions have been detected, and not the dynamic mutations observed in Fragile X syndrome. More recently a knock-in mouse model has been generated in which the murine (CGG)8 repeat within the endogenous Fmr1 gene was replaced by a human (CGG)98 repeat using a homologous recombination technique in embryonic stem (ES) cells.19 Importantly, minimal changes to the murine Fmr1 promoter were made when the targeting construct containing the human (CGG)98 repeat was generated. These CGG KI mice show moderate instability upon paternal and maternal transmission, and both expansions and contractions have been observed.20 Subsequently CGG KI mice were bred over several generations to establish transgenic lines with expanded alleles up to 230 CGG repeats.19 Although expected, no methylation of the Fmr1 gene has been found even with these longer CGG repeat expansions. Additional studies also demonstrated small (less that 10 CGG repeats) somatic instability in these CGG KI mice.21 Recently a similar knock-in mouse has been described with an initial (CGG)118 tract.22 These mice also show some repeat instability with a bias towards expansions.

Molecular findings

The observation that the premutation CGG expansion of between 55-200 trinucleotide repeats was associated with a neurodegenerative syndrome in elderly males, now known as FXTAS,23 led to renewed interest in both (CGG)98 and (CGG)118 knock-in mice,. The brains of these CGG KI mice show elevated Fmr1 mRNA levels and reduced Fmrp expression, and this is consistent with what has been reported in FXTAS.3 Importantly, a average 2-fold elevation in Fmr1 mRNA levels was detected as early as 1 week of age in (CGG)98 KI mice that persisted throughout development.21 This early elevation in Fmr1 mRNA indicates the potential for an as yet undocumented developmental phenotype in human FXTAS. The increase in Fmr1 mRNA levels in the CGG KI mice was not correlated with the length of the CGG repeat, and this is in contrast to the linear correlation between FMR1 mRNA levels and repeat size reported in human FXTAS.24-26 However, these human data were obtained from RNA isolated from peripheral blood or EBV-transformed lymphoblasts and not from brain homogenates, and brain Fmr1 mRNA levels are reported to be higher than in blood (Tassone, et al, 2004). Entezam and colleagues were able to show a direct relationship between repeat size and Fmr1 mRNA levels in brains of their exCGG mice, however, the number of mice studied for the different repeat sizes were limited.22

Both CGG KI mouse strains show an inverse correlation between CGG repeat length and Fmrp expression in brain by Western blot analysis.11, 22, 27 That is, reduced Fmrp expression occurs in spite of elevated levels of Fmr1 mRNA. One possibility to explain this paradox is that the exCGG expansion in the 5′ UTR of the transcript hampers the initiation of translation at the ribosome, possibly through the formation of quadruplex CGG secondary structures.28 The cellular mechanisms that result in enhanced transcription of Fmr1 are unknown at present. Changes in the levels of Fmrp in the brain also appears to be brain region-specific with significant reductions in many region of the brain, while expression remains relatively high in the hippocampus.22, 29

Neuropathology

As a further parallel between human FXTAS and the CGG KI mice, both show the presence of ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in many regions of the brain. The presence of these inclusions is a key neuropathological feature of FXTAS in humans.21, 22 Inclusions have now been identified in many brain regions, including cerebral cortex, olfactory nucleus, parafascicular thalamic nucleus, medial mammillary nucleus and colliculus inferior, cerebellum, amygdala and pontine nucleus at 72 weeks of age.21, 27 In addition, the size of the inclusions correlated significantly with the age of CGG KI mice, with small inclusions found in younger mice. Interestingly, the gradual increase in the size of the inclusions and the percent of ubiquitin-positive neurons appears to parallel the progressive development of the neurological phenotype of FXTAS in humans.30 In addition, brain regions showing the presence of intranuclear inclusions correlate with the clinical features in symptomatic FXTAS patients. Systematic analysis of these inclusions using immunohistochemistry shows the presence of ubiquitin, molecular chaperone Hsp40, 20S proteasome complex and DNA repair-ubiquitin-associated HR23B.21, 31 Notably, Fmrp was not detected in the inclusions.

Another neuropathological finding in human FXTAS is the presence of Purkinje cell degeneration.32 However, this has only been observed in one of the CGG KI mouse lines.22 It is notable that in contrast to FXTAS in humans where inclusions are common in astrocytes,15, 32 the existing CGG KI mouse lines show relatively few, if any inclusions in astrocytes. However, recent data have demonstrated the presence of inclusions in GFAP-positive astrocytes as well, although still at low levels (R. Berman; unpublished data)

Behavioral phenotype

Late-onset ataxia and memory impairments are key features of FXTAS. Similar behavioral impairments have also been found in CGG KI mice. Specifically, motor performance measured on the rotarod has been found to deline with age in CGG KI mice,33 and this impairment may be related to the progressive gait and ataxia characteristics of FXTAS patients.23 Spatial learning and memory in the Morris water maze is also impaired in CGG KI tested at 52 weeks of age.33 More recent studies in these mice indicate that there are also deficits in spatial pattern separation and spatial object recognition using behavioral tests developed to assess these cognitive functions in rodents.34 These deficits appear to parallel the impairments in memory and executive function in FXTAS patients, some of whom eventually develop dementia.3, 35, 36

Psychopathology

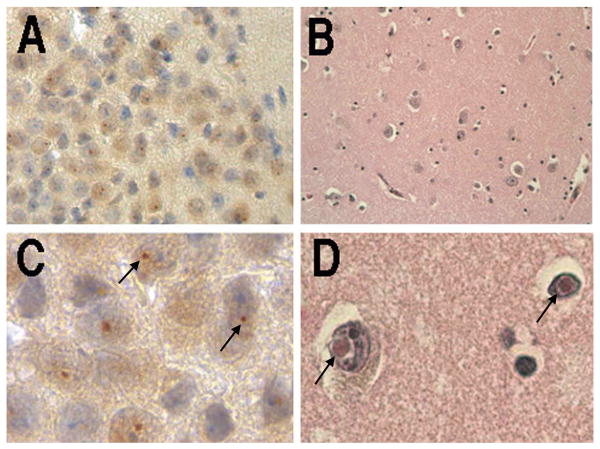

Recent studies have reported that elevated FMR1 mRNA levels were associated with increased psychopathology, including anxiety, depression and irritability in adult premutation carriers, with or without symptoms of FXTAS.30, 35, 37-40 These symptoms may reflect an elevated stress response, and this is supported by the finding of ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in the pituitary gland of autopsy brain material from patients with FXTAS.41, 42 This suggests that abnormal functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) may contribute to the pathophysiology of FXTAS. Studies in CGG KI mice at 72 weeks of age also show intranuclear ubiquitin-positive inclusions in both the pituitary and adrenal gland of 100-week-old mice.27 These mice also show evidence of increased anxiety in open field behaviour,33 and dramatically elevated corticosterone levels in serum in response to a mild stressor43. In addition, high percentages of intranuclear ubiquitin-positive inclusions are found in the amygdale in FXTAS and in CGG KI mice, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A,C) Ubiquitin positive intranuclear inclusions in the amygdale of a 72 week old KI mouse with 100 CGG trinucleotide repeats (low and high magnification). (B,D) Intranuclear inclusions in the amygdale of a FXTAS patient with 105 CGG trinucleotide repeats (low and high magnification). Arrows indicate inclusions.

Thus the altered regulation of the HPA axis and the evidence of histopathology in the amygdale may explain some of the psychopathology seen in male premutation carriers. A possibly related finding is that fMRI studies have reported reduced amygdala activation in male FXTAS premutation carriers in response to fearful faces, and this may also be related to the impaired social cognition in these patients.44 These results from the CGG KI mice indicate that further studies on the function of the HPA axis, stress response and cortisol levels will be important in order to better understand the neuropsychological symptoms of FXTAS.

Therapeutic implications

No effective therapy is currently available for FXTAS as existing treatments are limited to treating the symptoms. As a result, several important questions remain to be answered concerning the potential for future development of therapeutic interventions for FXTAS, and these questions can be directly addressed using appropriate mouse models. For example, identification of neurochemical abnormalities in CGG KI mice should lead to the development of rational pharmacotherapies for FXTAS. The development of inducible transgenic mouse models of FXTAS that allow for experimental control of gene expression, should define critical periods during development when pharmacotherapies are likely to be maximally effective and when genetic manipulations can halt or possible reverse disease progression in FXTAS. This information will be critical for the development of both pharmacotherapies and gene-targeted therapies (e.g., antisense oligonucleotides targeting the expanded CGG mutation). Although two different exCGG KI mouse lines are available, which exhibit at much of the symptomology observed in humans with FXTAS, they do not model human FXTAS in all aspects, including few inclusions in mouse astrocytes and absence of a significant degenerative neuropathology. Therefore, new transgenic mouse models need to be developed with conditional and inducible CGG repeat expression in neurons and/or astrocytes. These will allow testing for sufficiency, necessity (which cell types) and timing of reversibility of neuropathology (critical periods) for agents targeted to halt or reduce exCGG transcript expression (critical period). Such new transgenic mice could be engineered to show earlier onset, a more severe phenotype, or CGG expansion and expression restricted to specific cell types or brain regions. These developments should allow for future studies that provide greater insight into FXTAS, insight that could be applied to other repeat expansion diseases.

Conclusion

The development of mouse models of FXTAS has enabled studies to be carried out on the underlying molecular basis of FXTAS. Such research has provided critical information about the cellular events that occur with the onset and progression of the syndrome, including a greater understanding of the role of RNA toxicity in the pathophysiology of FXTAS. These contributions are important because of the difficulties in carrying out the necessary research in humans. In addition, the mouse CGG KI model offers new opportunities to explore the relationship between the number of CGG trinucleotide repeats and disease progression, and for understanding the role of toxic RNA gain-of-function in the pathogenesis of FXTAS. While the mouse model is not perfect, it does allow for the careful study of most of the key features of FXTAS. Future research using these models should provide important insights to into FXTAS that will be needed for the development and evaluation of effective therapeutics.

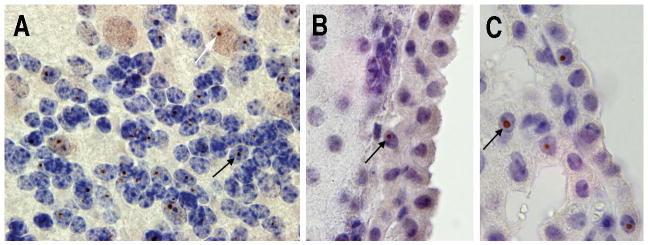

Figure 1.

(A). Ubituitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in cerebellar Purkinje neurons (white arrow) and granule cells (black arrow) in 100 week old CGG KI mouse. Ubiquitin-positive inclusions (black arrows) in ependymal cells in a 72 week old CGG KI mousse (B) and a 91 week old CGG KI Mouse (C).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH-NINDS grants NS062411 and RR024922, NIH Roadmap Initiative UL1 1 DE019583-02, NIDCR, and NCRR R13 RR023236.

References

- 1.Hagerman RJ, Ono MY, Hagerman PJ. Recent advances in fragile X: a model for autism and neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:490–496. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000179485.39520.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagerman RJ, Leavitt BR, Farzin F, et al. Fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) in females with the FMR1 premutation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1051–1056. doi: 10.1086/420700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS) Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:25–30. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bontekoe CJ, de Graaff E, Nieuwenhuizen IM, et al. FMR1 premutation allele (CGG)81 is stable in mice. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willemsen R, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Reis S, et al. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bontekoe CJ, Bakker CE, Nieuwenhuizen IM, et al. Instability of a (CGG)98 repeat in the Fmr1 promoter. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1693–1699. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hessl D, Tassone F, Loesch DZ, et al. Abnormal elevation of FMR1 mRNA is associated with psychological symptoms in individuals with the fragile X premutation. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Chamberlain WD, et al. Transcription of the FMR1 gene in individuals with fragile X syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. 2000;97:195–203. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<195::AID-AJMG1037>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, et al. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenneson A, Zhang F, Hagedorn CH, et al. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouwer JR, Huizer K, Severijnen LA, et al. CGG-repeat length and neuropathological and molecular correlates in a mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1671–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, et al. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Dam D, Errijgers V, Kooy RF, et al. Cognitive decline, neuromotor and behavioural disturbances in a mouse model for fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Behav Brain Res. 2005;162:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hessl D, Rivera S, Koldeewyn K, et al. Amygdala dysfunction in men with the fragile X premutation. Brain. 2006 doi: 10.1093/brain/awl338. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greco CM, Berman RF, Martin RM, et al. Neuropathology of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Brain. 2006;129:243–255. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bontekoe CJM, de Graaff E, Nieuwenhuizen IM, et al. FMR1 premutation allele is stable in mice. Eur J Hum Genet. 1997;5:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavedan CN, Garrett L, Nussbaum RL. Trinucleotide repeats (CGG)22TGG(CGG)43TGG(CGG)21 from the fragile X gene remain stable in transgenic mice. Hum Genet. 1997;100:407–414. doi: 10.1007/s004390050525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavedan C, Grabczyk E, Usdin K, et al. Long uninterrupted CGG repeats within the first exon of the human FMR1 gene are not intrinsically unstable in transgenic mice. Genomics. 1998;50:229–240. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bontekoe CJ, Bakker CE, Nieuwenhuizen IM, et al. Instability of a (CGG)(98) repeat in the Fmr1 promoter. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1693–1699. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouwer JR, Mientjes EJ, Bakker CE, et al. Elevated Fmr1 mRNA levels and reduced protein expression in a mouse model with an unmethylated Fragile X full mutation. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willemsen R, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Reis S, et al. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Entezam A, Biacsi R, Orrison B, et al. Regional FMRP deficits and large repeat expansions into the full mutation range in a new Fragile X premutation mouse model. Gene. 2007;395:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, et al. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenneson A, Zhang F, Hagedorn CH, et al. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen EG, He W, Yadav-Shah M, et al. A study of the distributional characteristics of FMR1 transcript levels in 238 individuals. Hum Genet. 2004;114:439–447. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Primerano B, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, et al. Reduced FMR1 mRNA translation efficiency in Fragile X patients with premutations. RNA. 2002;8:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brouwer JR, Severijnen E, de Jong FH, et al. Altered hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis regulation in the expanded CGG-repeat mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ofer N, Weisman-Shomer P, Shklover J, et al. The quadruplex r(CGG)n destabilizing cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 cooperates with hnRNPs to increase the translation efficiency of fragile X premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brouwer JR, Mientjes EJ, Bakker CE, et al. Elevated Fmr1 mRNA levels and reduced protein expression in a mouse model with an unmethylated Fragile X full mutation. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacquemont S, Farzin F, Hall D, et al. Aging in individuals with the FMR1 mutation. Am J Ment Retard. 2004;109:154–164. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<154:AIIWTF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergink S, Severijnen LA, Wijgers N, et al. The DNA repair-ubiquitin-associated HR23 proteins are constituents of neuronal inclusions in specific neurodegenerative disorders without hampering DNA repair. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greco CM, Hagerman RJ, Tassone F, et al. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain. 2002;125:1760–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Dam D, Errijgers V, Kooy RF, et al. Cognitive decline, neuromotor and behavioural disturbances in a mouse model for Fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;162:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunsaker MR, Rosenberg JS, Kesner RP. The role of the dentate gyrus, CA3a,b, and CA3c for detecting spatial and environmental novelty. Hippocampus. 2008;18:1064–1073. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grigsby J, Brega AG, Engle K, et al. Cognitive profile of fragile X premutation carriers with and without fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:48–60. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornish KM, Li L, Kogan CS, et al. Age-dependent cognitive changes in carriers of the fragile X syndrome. Cortex. 2008;44:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hessl D, Tassone F, Loesch DZ, et al. Abnormal elevation of FMR1 mRNA is associated with psychological symptoms in individuals with the fragile X premutation. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139B:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacalman S, Farzin F, Bourgeois JA, et al. Psychiatric Phenotype of the Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS) in Males: Newly Described Fronto-Subcortical Dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:87–94. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourgeois JA, Cogswell JB, Hessl D, et al. Cognitive, anxiety and mood disorders in the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter JE, Allen EG, Abramowitz A, et al. Investigation of Phenotypes Associated with Mood and Anxiety Among Male and Female Fragile X Premutation Carriers. Behav Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9214-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Louis E, Moskowitz C, Friez M, et al. Parkinsonism, dysautonomia, and intranuclear inclusions in a fragile X carrier: A clinical-pathological study. Mov Disord. 2006;27:193–201. doi: 10.1002/mds.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greco CM, Soontrapornchai K, Wirojanan J, et al. Testicular and pituitary inclusion formation in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:1434–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brouwer JR, Severijnen E, de Jong FH, et al. Altered hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis regulation in the expanded CGG-repeat mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hessl D, Rivera S, Koldewyn K, et al. Amygdala dysfunction in men with the fragile X premutation. Brain. 2006 doi: 10.1093/brain/awl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]