Down-Regulation of Hypothalamic Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Messenger Ribonucleic Acid (mRNA) Precedes Early-Life Experience-Induced Changes in Hippocampal Glucocorticoid Receptor mRNA (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 May 24.

Published in final edited form as: Endocrinology. 2001 Jan;142(1):89–97. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7917

Abstract

Early-life experiences, including maternal interaction, profoundly influence hormonal stress responses during adulthood. In rats, daily handling during a critical neonatal period leads to a significant and permanent modulation of key molecules that govern hormonal secretion in response to stress. Thus, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression is increased, whereas hypothalamic CRH-messenger RNA (mRNA) levels and stress-induced glucocorticoid release are reduced in adult rats handled early in life. Recent studies have highlighted the role of augmented maternal sensory input to handled rats as a key determinant of these changes. However, the molecular mechanisms, and particularly the critical, early events leading from enhanced sensory experience to long-lasting modulation of GR and CRH gene expression, remain largely unresolved.

To elucidate the critical primary genes governing this molecular cascade, we determined the sequence of changes in GR-mRNA levels and in hypothalamic and amygdala CRH-mRNA expression at three developmental ages, and the temporal relationship between each of these changes and the emergence of reduced hormonal stress-responses.

Down-regulation of hypothalamic CRH-mRNA levels in daily-handled rats was evident already by postnatal day 9, and was sustained through postnatal days 23 and 45, i.e. beyond puberty. In contrast, handling-related up-regulation of hippocampal GR-mRNA expression emerged subsequent to the 23rd postnatal day, i.e. much later than changes in hypothalamic CRH expression. The hormonal stress response of handled rats was reduced starting before postnatal day 23. These findings indicate that early, rapid, and persistent changes of hypothalamic CRH gene expression may play a critical role in the mechanism(s) by which early-life experience influences the hormonal stress-response long-term.

EARLY-LIFE EXPERIENCE influences both hormonal and behavioral responses to stress throughout life (1–5). In the human, early-life experiences may modulate stress-responses and coping, with long-term implications for emotional health and cognitive function (5). In rats, daily handling during a critical neonatal period leads to a significantly reduced stress response (compared with animals raised without any disturbance) that persists throughout life (1–2, 4). More recently, the effects of early-life handling were shown to result from increased maternal licking and grooming upon returning handled pups to their home cages (6–8). However, the molecular basis of the profound changes of pup hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis tone induced by altered maternal sensory input, changes that distinguish adult rats raised undisturbed from those experiencing early-life-handling, have remained unclear (4, 7, 9). Specifically, the mechanism(s) by which these neonatal events influence the expression and function of key HPA neuromodulators, and the nature of critical, early stages of this chain of events remain largely unresolved.

In adult rats that were handled early in life, increased expression of GR in hippocampus and frontal cortex and reduced expression of the hypothalamic stress-mediating neuropeptide, CRH, have been considered to underlie their attenuated stress response compared with that of rats raised undisturbed (10, 11). It is generally recognized that complex sensory and integrative pathways must be involved in transducing altered maternal-derived sensory input into permanent modulation of the stress response (12). However, within the immature rat HPA, an early, critical effect of this sensory input on hippocampal neuronal plasticity, manifesting as increased GR expression, has been proposed (4, 6–8). These increased GR levels, in turn, more efficiently transmit negative glucocorticoid feedback to the HPA axis (13), down-regulating hypothalamic CRH and the subsequent responses to stress.

It may be reasoned that if a primary effect of handling/maternal input on the immature rat HPA axis involves up-regulation of GR-messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in hippocampus, then this enhancement of GR-mRNA levels should precede modulation of hypothalamic CRH-mRNA. Thus, there should be a period, during the early evolution of handling effects on the hippocampal-HPA axis, when these neuroplastic hippocampal changes are already apparent, whereas the consequent functional alterations of hypothalamic CRH expression have not yet emerged. Alternatively, other genes governing the extent and magnitude of the hormonal stress response may be involved in mechanism for the long-lasting effects of early-life handling. For example, modulation of hypothalamic CRH expression, found to result from several early life experiences (14–16), may be considered. If the effects of handling/maternal input on long-term HPA function involve early down-regulation of CRH-mRNA levels in hypothalamus, then these changes in CRH gene expression should precede alterations in GR-mRNA levels. Thus, this study aimed to gain insight about the mechanisms for the effect of early-life experience on immature rat HPA axis by determining the precise timing and sequence of handling-induced alterations of CRH-mRNA and GR-mRNA expression in specific brain regions involved in hippocampal-HPA axis regulation.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

The overall strategy was to determine the magnitude, time of onset, and sequence of the molecular cascade induced by subjecting neonatal rats to handling/alteration of maternal input. Because the goal of this study was to discern early molecular changes resulting from the handling experience, and because it has been documented that daily handling during the first 5 or 7 postnatal days is required and sufficient to influence the HPA-axis and the stress response permanently (1–2, 17), rats were handled on days 2–8 of life. Parameters investigated included GR-mRNA expression in hippocampal formation and in frontal cortex, and CRH-mRNA levels in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and amygdaloid central nucleus (ACe). The relationship of these molecular changes to the onset of handling-induced alteration in the stress-response was established.

Expression of CRH and of GR was evaluated on postnatal days 9, 23, and 45 in rats handled daily during postnatal days 2–8, compared with those left undisturbed. The first time-point was chosen to coincide with the end of the daily handling regimen. Day 23 was chosen as a prepubertal time-point that is comfortably beyond the established critical period for neuroplasticity induced by the handling experience (1, 17), i.e. a time-point when the effects of early-life experience should be stably ingrained. Day 45 was chosen as a postpubertal time-point, allowing evaluation of potential changes in GR-mRNA or CRH-mRNA expression that may emerge with puberty. In addition, the magnitude of the hormonal stress-response to age-appropriate stressful stimuli was determined on the same developmental days in handled and in undisturbed rat groups.

Animals

Immature rats were offspring of timed-pregnancy Sprague Dawley rats (Zivic-Miller Laboratories, Inc., Zelienople, PA), and maintained in NIH approved, uncrowded, temperature-controlled animal facilities, on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with unlimited access to lab chow and water. Cages were inspected for presence of pups at 12-h intervals, and the date of birth was considered day 0. All experimental manipulations were conducted at 0800–0900, to minimize potential diurnal variability in HPA-associated gene expression and responses to stress (18, 19). All experiments were carried out according to the NIH guidelines for the care of experimental animals with approval by the Institutional Animal Care Committee. Group size (n) was 6–10 rats per treatment per time-point. Both genders were evaluated on day 9, and males only were used at the 23 and 45-day time-points.

Early-life manipulations

- Daily handling was performed on days 2–8 (the rationale for this relatively short handling paradigm is provided in the experimental design, above). Handling consisted of removing the mother followed by the pups from their home cages, and placing the pups in a cage lined with bedding for 15 min. Pups were returned to their home cage first, followed by the mother (10, 20, 21). 2) Undisturbed rats were inspected once on the first day of life. During postnatal days 2–8, litters were completely undisturbed in a quiet corner of the animal facility, without bedding changes. Water and food were gently applied to the top of the cage. Starting on postnatal day 9, all surviving experimental groups were housed under routine lab conditions, including cage changes twice a week and weaning on day 21.

Methods of age-appropriate stress

Restraint, a powerful stress in adult rats, is a poor stress for neonatal rats who are accustomed to confinement by their mother's body. In contrast, cold is a poor stress for furred adults with fully developed metabolic responses. Therefore, cold was chosen for 9- day-old rats and restraint for older ages.

For all experiments, time 0 was considered the onset of age-appropriate stressors, and these were imposed rapidly after removing rats from home cages. For 9-day-old rats, cold stress, extensively characterized previously (14, 16, 22), was used. Briefly, rats were placed in individual glass jars containing ice, in a cold-room (4 C) for 12 min. Following cold stress, pups were placed on a euthermic pad (33–34 C) and killed by decapitation at 30 or 60 min following the onset of cold stress. Older rats were subjected to restraint stress for 20 min (10) and were killed at the time points coinciding with those chosen by these authors: before stress (time 0 here), at the termination of restraint (20 min here) and 1 h after the end of restraint (80 min here). For 23-day-old rats, restrainers were fashioned via saran-wrapping the animals inside the larger containers; for 45-day-old rats, tubular plastic restrainers were used.

Tissue handling and hormonal assays

Brains were rapidly dissected onto powdered dry ice and stored at −80 C. Coronal sections (20 μm) spanning prefrontal cortex to ventral hippocampus (23) were cut using a cryotome. Sections were sorted into matched series for in situ hybridization histochemistry as described in detail previously (14, 16, 22, 24). Trunk blood was collected for analysis of plasma ACTH and corticosterone (CORT) using commercial RIA kits (INCSTAR Corp., Stillwater, MN, and ICN, Irvine, CA) as previously described (25). Assay sensitivities were 15 pg/ml for ACTH and 0.5 mg/dl for CORT; interassay variabilities averaged 5–10%.

In situ hybridization histochemistry (ISH) and probe preparation

ISH and probe labeling were performed as described previously for oligonucleotide probes (14, 16, 22) or complementary RNA probes (25, 26). Briefly, for CRH-mRNA analysis, sections were brought to room temperature, air dried, and fixed in fresh 4% buffered paraformaldehyde for 20 min, followed by dehydration and rehydration through graded ethanols. Sections were exposed to 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 m triethanolamine (pH 8) for 8 min and were dehydrated through graded ethanols. Prehybridization and hybridization steps were performed in a humidified chamber at 40 C in a solution of 50% formamide, 5× SET, 0.2% SDS, 5× Denhardt's, 0.5 mg/ml salmon sperm DNA, 0.25 mg/ml yeast transfer RNA, 100 mm dithiothreitol, and 10% Dextran sulfate. Following a 1-h prehybridization, sections were hybridized overnight with 0.5 3 106 cpm of 35S-labeled oligonucleotide probe. Post hybridization, sections were washed, most stringently at 0.3 × SSC. For detection of GR-mRNA, sections were hybridized overnight at 55 C with 1 × 106 cpm of 35S labeled ribonucleotide probe. After hybridization, the sections were washed in 2 × SSC for 5 min at room temperature and were digested with RNase (200 μg/ml RNase A; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in a 10 M Tris HCl (pH = 8)/NaCl for 30 min at 37 C. Sections underwent serial washes of increasing stringency at 55 C, the most stringent being at 0.03 × SSC for 1 h. For both procedures, sections were then dehydrated through 100% ethanol, air dried and apposed to film (Hyperfilm β-Max, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Arlington Heights, IL) for 7–14 days. Representative sections were also dipped in NTB-2 nuclear emulsion (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY) and exposed for 4 – 6 weeks.

Acquisition and quantitative analysis of ISH signal, and statistical considerations

Semiquantitative analyses of CRH-mRNA and GR-mRNA were performed following in situ hybridization without knowledge of treatment, as described in detail previously (16, 24, 25). Digitized images of each brain section were analyzed using the ImageTool software program (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX). Densities were calibrated using 14C standards and are expressed in nCi/g, after correcting for background by subtracting the density of the hybridization signal over the corpus callosum. Hippocampal formation sections were analyzed at coronal levels corresponding to 2.0–2.9 mm, 2.6–3.5 mm, and 3.2–4.1 mm anterior to bregma in 9-, 23-, and 45-day-old rats, respectively.

In hippocampus of the 9-day-old rat, GR-mRNA signal was analyzed only in the CA1 region (see Fig. 3B), based on the established distribution of GR-mRNA in the developing rat hippocampus (26, 27). At older age-groups, GR-mRNA was also measured over the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus (DG; 13, 27). Hypothalamic PVN was sampled at levels including the dorsomedial parvocellular cell group expressing CRH and GR-mRNA (3.5–3.8, 4.4–5.0, and 5.0–4.4 mm anterior to bregma for 9-, 23-, and 45-day-old rats, respectively). Frontal cortex sections were analyzed at coronal levels corresponding to 2.3–3.2 mm anterior to the bregma in the 9-day-old rat, 2.6–4.4 mm in the 23-day-old rat, and 3.2–5.6 in the 45-dayold rat. ACe was analyzed at levels corresponding to 2.3–3.2 mm, 3.8–5.0, and 4.4–5.6 mm anterior to bregma for 9-, 23-, and 45-day-old rats, respectively. Optical densities from three optimal sections were averaged to generate an expression value for each region. These values were then used to calculate group means (n = animal number). Statistical significance (P < 0.05) of observed quantitative differences among experimental groups at each time-point and brain region was evaluated using unpaired Student's t test, with Welch's correction for unequal variance when indicated (16, 24). Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of early-life experience and of stress on plasma ACTH levels.

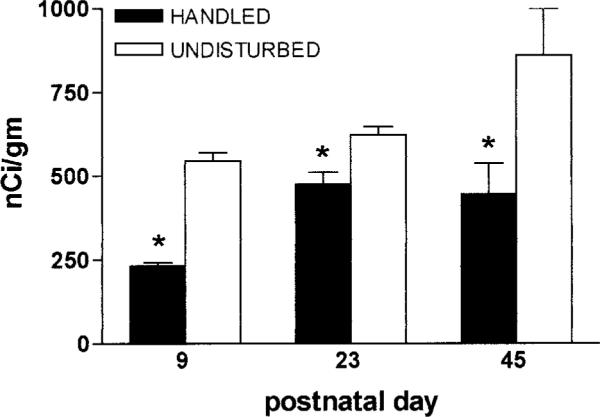

FIG. 3.

CRH expression in the PVN is persistently down-regulated after the handling/altered maternal input experience. Analysis of in situ hybridizations of sections from 9-, 23-, and 45-day-old rats reveals significantly (*) lower CRH-mRNA signal compared with rats left undisturbed. Optical densities from three sections were averaged (n = 6–10 animals per time-point). Values are expressed as means ± SEM.

Results

CRH gene expression in hypothalamic PVN is down-regulated by daily handling as early as the 9th postnatal day

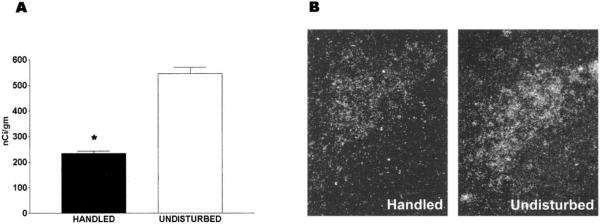

As shown in Fig. 1A, CRH-mRNA levels in PVN of the 9-day-old, daily-handled rats were significantly lower (233.3 ± 8.8 nCi/g) than those of undisturbed pups (545.0 ± 25.0 nCi/g, P < 0.01). Decreased CRH-mRNA signal over PVN is evident in a dark-field photomicrograph derived from a handled rat, compared with a matched section from an undisturbed animal (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

CRH-mRNA expression in paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of 9-day-old rats experiencing daily handling on postnatal days 2–8 is reduced compared with that of undisturbed immature rats. A, Semiquantitative analysis of signal over PVN was achieved after in situ hybridization of matched coronal sections. Optical densities from three sections were averaged to generate the mRNA level for each animal, which was then used to calculate group means (n = 6–10 pups). Values are expressed as means ± SEM; *, P < 0.05. B, Decreased CRH-mRNA signal over PVN is evident in a dark-field photomicrograph derived from a 9-day-old handled rat, compared with a matched section from an undisturbed animal.

GR gene expression in hippocampal CA1 is not yet altered in handled 9-day-old rats

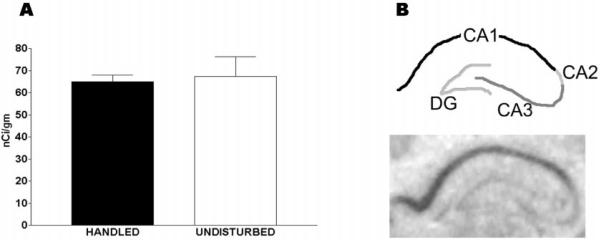

Figure 2A shows that, on postnatal day 9, GR-mRNA levels in hippocampal CA1 did not differ between rats that were handled daily on postnatal days 2–8 and those raised undisturbed (65.0 ± 2.9 nCi/g vs. 67.3 ± 8.96 nCi/g). Figure 2B demonstrates robust GR-mRNA signal in CA1 at this age, but (in contrast to older animals) little GR expression in the dentate gyrus granule cell layer.

FIG. 2.

Glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-mRNA levels in hippocampal CA1 of 9-day-old rats experiencing daily handling on postnatal days 2–8 do not differ from those of undisturbed pups. A, Semiquantitative analysis of signal over hippocampal CA1 was achieved after in situ hybridization of matched coronal sections. Optical densities from three sections per animal were averaged (n = 6–10 pups). No significant difference between groups was observed. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (Note: the same data are depicted also in Fig. 4A). B, A coronal brain section from an hippocampal formation of a 9-day-old rat demonstrates that robust GR-mRNA expression at that age is confined primarily to CA1.

Modulation of CRH expression in PVN upon handling is sustained beyond the first three weeks of life and is not accompanied by changes in CRH-mRNA levels in amygdala

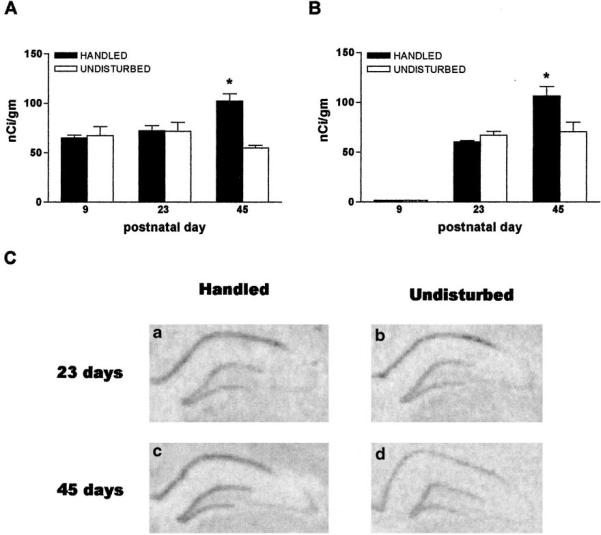

To further clarify the evolution of CRH-mRNA expression as a consequence of early-life experience, two additional ages were examined. As shown in Fig. 3, CRH-mRNA levels in PVN were persistently reduced in handled rats, when measured on post-natal day 23 (475.8 ± 35.4 nCi/g handled vs. 622.5 ± 24.8 nCi/g in undisturbed animals) and on day 45 (446.0 ± 92.0 nCi/g vs. 860.0 ± 140.0 nCi/g). In contrast, analysis of CRH-mRNA levels in ACe did not reveal significant effects of early-life handling. Thus, CRH-mRNA levels in ACe in handled and undisturbed rats averaged 69.0 ± 5.2 nCi/g and 57.1 ± 9.1 nCi/g, respectively on postnatal day 23. By day 45, CRH-mRNA levels averaged 82.5 ± 7.5 nCi/g in handled pups, and 76.7 ± 3.3 nCi/g in the undisturbed cohort.

GR gene expression in hippocampal CA1 of rats subjected to early-life handling is up-regulated on the 45th, but not on the 23rd postnatal day

To better resolve the timing of GR up-regulation, two additional ages were examined. Figure 4A shows that GR-mRNA levels in hippocampal CA1 did not differ between daily-handled and undisturbed rats immediately following the handling paradigm (day 9) or 2 weeks later (for day 23: 72.1 ± 5.3 nCi/g in handled vs. 71.8 ± 8.9 nCi/g in undisturbed rats). However, by the 45th postnatal day, following puberty, GR-mRNA levels were higher in rats experiencing early-life handling (102.3 ± 7.4 nCi/g vs. 54.7 ± 2.8 nCi/g, P < 0.01). In the 9-day-old rat, little GR-gene expression was found over the DG granule cell layer (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the early effects of the experimental manipulations described here on this transcript's expression could not be determined. Comparison of GR-mRNA signal over DG in 23- and 45-day old rats revealed an up-regulation of GR expression on the 45th postnatal day in the handled group (Fig. 4B, 106.7 ± 9.5 nCi/g vs. 70.7 ± 9.4 nCi/g), as shown also in Fig. 4C. This figure depicts coronal brain sections at the level of the dorsal hippocampus, following in situ hybridization for GR-mRNA. Similar expression magnitude and pattern in handled (A) and undisturbed (B) rats are evident on postnatal day 23. By postnatal day 45, GR signal is enhanced in a rat subjected to early-life handling (C) compared with one raised undisturbed (D).

FIG. 4.

Time-course of the effects of early-life experience on glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-mRNA expression in the hippocampal formation. A, Significant (*) up-regulation of GR-mRNA levels in hippocampal CA1 of daily handled rats emerges starting at the 45-day time-point (but not on postnatal days (P) 9 or 23). B, In the dentate gyrus granule cell layer, little GR-mRNA signal is apparent in either group on P9 (see Fig. 2). Enhanced GR-mRNA expression is evident on P45 in the handled group. Semiquantitative analysis was achieved as described in Figs. 2–5; n = 6–10 animals per group per time-point. C, In situ hybridization for GR-mRNA demonstrates similar expression patterns and magnitude in handled (a) and undisturbed (b) rats on P23. By P45, GR signal is enhanced in a rat subjected to early-life handling (c) compared with one raised undisturbed (d).

Early-life handling experience does not influence GR-mRNA levels in hypothalamic PVN and frontal cortex

Analysis of GR-mRNA levels in PVN and in frontal cortex failed to demonstrate effects of early-life handling. Thus, GR-mRNA levels in PVN of handled and undisturbed rats averaged 72.3 ± 7.9 nCi/g and 63.0 ± 13.0 nCi/g, respectively, on postnatal day 9; corresponding values were 71.7 ± 4.4 nCi/g and 75.3 ± 4.5 nCi/g on postnatal day 23. Finally, on postnatal day 45, GR-mRNA levels in PVN averaged 70.0 ± 20.0 and 54.3 ± 6.7 nCi/g, respectively. In frontal cortex, levels of GR-mRNA were 46.0 ± 5.6 in handled rats and 46.7 ± 2.4 nCi/g in undisturbed rats on postnatal day 9. In 23-day-old rats GR-mRNA levels averaged 25.1 ± 2.2 and 27.7 ± 1.7 nCi/g in handled and undisturbed rats, respectively, and no differences were observed also on postnatal day 45 (52.0 ± 10.5 nCi/g and 49.0 ± 2.1 nCi/g, respectively in handled and undisturbed groups).

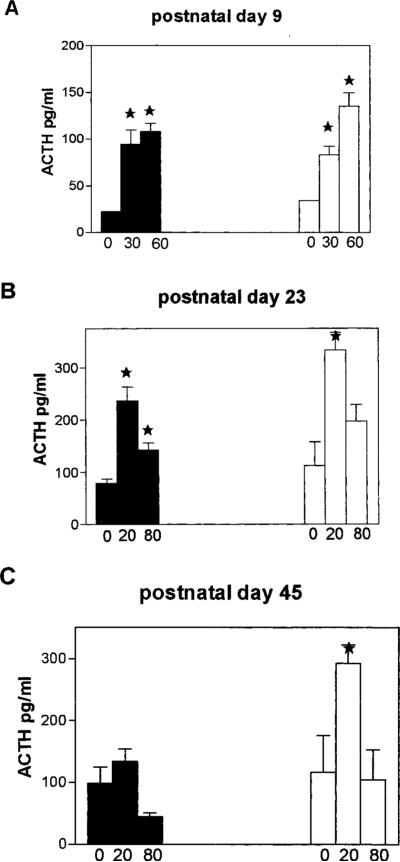

Early-life experiences influence the hormonal stress response by the 23rd and 45th postnatal days, but not on postnatal day 9

Analyses of the hormonal stress responses of rats handled early in life compared with the undisturbed groups were carried out on postnatal days 9, 23, and 45. On day 9, robust elevations of both plasma ACTH and CORT in response to age-appropriate stress were observed. Figure 5A shows significant increases of plasma ACTH at both time points after stress onset. Whereas a robust effect of stress was noted (F2,15 = 11; P = 0.0016), no effect of the early life experience was revealed by two-way ANOVA (P = 0.59). CORT levels were in line with ACTH values: basal AM levels were 0.99 ± 0.12 and 1.14 ± 0.15 mg/dl in the handled and undisturbed groups, respectively. In response to stress, CORT levels of both groups rose, to 2.67 ± 0.41 and 2.59 ± 0.35 mg/dl at the 20 min time-point and 4.49 ± 0.40 and 3.51 ± 0.26 μg/dl at 60 min. Two-way ANOVA revealed a robust effect of stress (F2,30 547.68; P < 0.0001), but not of the early-life experience (F1,30 = 1.54; P = 0.22). By the 23rd day of life, (i.e. before alteration of hippocampal GR-mRNA) significant effects of the early-life handling experience on plasma ACTH and CORT responses to stress were evident. Figure 5B demonstrates a diminished induction of plasma ACTH by stress in the handled group: two-way ANOVA revealed both an effect of stress (F2,35 = 20.30 P < 0.001) and a robust effect of the early life treatment (F = 6.32; P = 0.017). Plasma CORT response to stress and early-life treatment was similar, showing significant effects of stress (F2,16 = 29.55) and of handling (F1,16 = 12.77). As shown in Fig. 5C, this effect of early life treatment on the hormonal stress response persisted at least to postnatal day 45 when, in addition to robust effects of stress (P = 0.0046), two-way ANOVA showed a strong handling effect (F = 7.7; P = 0.018). As evident from the figure, basal AM levels of ACTH were not significantly different in handled and undisturbed groups at all three ages. Similarly, for CORT (see 9 day levels, above) basal values were 2.39 ± 0.44 and 4.42 ± 0.44 μg/dl on postnatal day 23, and 3.496±0.86 vs. 4.81 ± 0.41 μg/dl on postnatal day 45.

FIG. 5.

Basal and stress-induced plasma ACTH as a function of age and early-life experience. A, On P9, plasma ACTH levels increase significantly (*) after age-appropriate stress, but do not differ in handled vs. undisturbed animals (P = 0.59, effect of handling, two-way ANOVA). B, By P23, rats handled early in life demonstrate lower ACTH output, compared with undisturbed groups (effect of handling, two-way ANOVA: F1,35 = 6.32; P = 0.017). It should be noted that at this age, hippocampal GR expression does not distinguish between handled and undisturbed groups, whereas hypothalamic CRH-mRNA levels are lower in handled pups. C, Reduced neuroendocrine stress response persists in 45-day-old rats that were handled on P2-P8 (effect of handling, F = 7.7; P = 0.018). Robust effects of stress on ACTH levels is evident at all ages (note different y-axis scale on P9; two-way ANOVA, F2,13 = 11 at P9; F2,35 = 20 at P23; F2,24 = 5 at P45. P < 0.02 for all). Bars in each group denote mean ± SEM of ACTH levels before stress, and at the two time points (in minutes) after its onset as noted in the graphs (see Materials and Methods for detailed description). Error bars are not shown for P9 basal ACTH values because samples were pooled.

Discussion

The principal findings of the current study are: 1) down-regulation of CRH-mRNA levels by the early-life daily handling experience occurs rapidly and is evident by the 9th postnatal day. In addition, this modulation of hypothalamic CRH expression persists at least beyond puberty; 2) handling-related up-regulation of hippocampal GR-mRNA expression arises subsequent to the 23rd postnatal day, significantly later than changes in hypothalamic CRH expression; 3) reduced magnitude of the hormonal stress response of handled rats emerges between the 9th and 23rd days, i.e. subsequent to alteration of CRH-mRNA expression, but before significant changes in GR-mRNA levels. Taken together, these finding support the notion that diminished hypothalamic CRH expression is required for handling-induced reduction in stress responses. The latter, in turn may influence hippocampal GR expression.

Early-life experience influences the stress response profoundly and permanently

Modulation of early-life experience of the neonatal rat may permanently influence the expression of stress-mediating molecules and the hormonal responses to stress (1, 8). Thus, exposure of neonatal rats to age-appropriate physiologic or psychologic stressors (14, 16) or to prolonged or repeated maternal separation (10, 15, 22, 28) has resulted in immediate and/or long-term enhancement of sensitivity to further stress. In contrast, compared with animals raised without any disturbance, daily handling of rat pups during the first 3 weeks of life has led to robust reduction in the stress response that persists throughout the animal's life (1, 4). More recently, changes in maternal behavior (increased grooming and licking), observed on returning pups to their cages, have been implicated in mediating these effects of handling on the neonatal rat (6–8). Sensory input derived from altered maternal behavior is generally believed to influence the pup's HPA-axis at the molecular level, leading eventually to significantly reduced responses to subsequent stress (4, 6). Thus, enhanced GR expression in hippocampus and frontal cortex (29, 30) and decreased levels of hypothalamic CRH expression (10, 11) of adult rats handled early in life have been considered to underlie their diminished stress response compared with that of those raised undisturbed.

The set-point and magnitude of the hormonal responses to stress are under tight and intricate regulation (31–33), and are influenced by both hippocampal GR and hypothalamic CRH function. In both mature and developing rat, CRH is released from hypothalamic peptidergic neurons within seconds of stress onset, to influence pituitary ACTH secretion and release of adrenal glucocorticoids (33–35). These hormones interact with GRs in hippocampus, PVN and pituitary (36–38) to negatively feed back onto the hormonal stress response (39). In addition, glucocorticoids regulate GR expression, thus further influencing the magnitude of HPA axis suppression (40, 41). Because of the known influence of glucocorticoids on hippocampal neuroplasticity—an effect requiring GR activation—alteration of GR expression has been proposed as a key mechanism for the effects of handling-induced changes in maternal-derived sensory input on HPA axis tone (4).

Down-regulation of hypothalamic CRH expression is an early, key consequence of the early-life handling experience, preceding alteration of GR-mRNA expression

The present study demonstrates that modulation of CRH-mRNA levels by neonatal handling occurs relatively rapidly and is detectable already by the 9th postnatal day. These early changes amplify previous data, showing that daily handling during the first 5–7 postnatal days is sufficient to influence the HPA-axis and the stress response permanently (1, 2, 17), data that provided the rationale for using an 8-day handling regimen in the current studies.

The early down-regulation of hypothalamic CRH expression persisted at least through early adulthood In contrast to the rapid modulation of hypothalamic CRH-mRNA expression, early (postnatal day 9) hippocampal GR-mRNA levels were not influenced by early-life handling. This finding is consistent with the notion that modulation of CRH-expression by early-life experience precedes (and is thus not a consequence of) GR-mediated changes in HPA axis tone. The age of onset of altered GR-mRNA levels after daily handling is not fully resolved. Although early (postnatal day 7) changes in hippocampal glucocorticoid binding have been observed (17), binding studies may not fully reflect changes in GR expression (42); indeed, some have failed to demonstrate any alteration of GR binding in adult rats handled as neonates (9). Published GR-mRNA data are limited to studies of adult animals, handled as neonates (29). The current study, focusing on molecular changes at the mRNA level, suggests that regulation of hypothalamic CRH expression may be an early—and thus key—target of the altered maternal-derived sensory input related to the handling maneuver.

How do sensory signals resulting from early-life handling alter CRH expression in PVN permanently?

It is generally established that daily handling during a critical postnatal period in the immature rat leads to augmented maternal sensory input to handled pups. Previous work from this laboratory has pointed to a chemically defined sensory signal-transduction pathway integrating maternal sensory input to modulate the central components of the HPA axis (25). This pathway involves a series of intercommunicating structures that relay and integrate sensory information: somatosensory signals from the spinal cord reach the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). NTS efferents heavily innervate the CRH-rich PVN (43), and via the parabrachial nucleus, the ACe, a key stress integrator (44, 45), thus positioning this pathway as a candidate for mediating HPA activation in response to diverse stimuli (43, 46, 47). Earlier work from this laboratory suggested that, in processing stress-modulating signals, specificity in this sensory-integrative pathway is derived from activation of CRH-expressing neurons signaling via the CRH type 2 receptor (CRF2). Thus, altered maternal sensory input (e.g. licking and grooming) was found to influence CRH-CRF2 signaling in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus (25), a region shown previously to regulate stress-related PVN function (48, 49). Further evidence for modulation of CRH expression in structures comprising this sensory integration pathway (e.g. in parabrachial nucleus) has been emerging (50, 51). Clearly, this proposed, chemically specified (CRH-CRF2) pathway functions within the broader context of neuroanatomical circuits using several neurotransmitters to influence HPA function. For example, direct noradrenergic input from NTS to PVN has been described (52), conveying stress-related signals, and likely stimulating PVN-CRH neurons (53–55). In addition, CRH is expressed in—and interacts with—noradrenergic locus ceruleus neurons (56–58). Indeed, early-life handling has been shown to modulate intercommunicating noradrenergic and CRH-expressing neurons in this circuit (7, 59). Other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, have also been implicated in regulating CRH expression and release both in and outside the hypothalamus (56, 60, 61).

Processing of sensory signals to influence stress-response magnitude and set-points likely involves the ACe, a key amygdaloid stress-integrator (12, 58, 62). This region, highly expressing CRH (50, 63), promotes PVN-mediated stress functions. Therefore, the current study examined for potential down-regulation of CRH expression in ACe following early-life handling. The absence of such changes indicates that if handling influences ACe to decrease positive input to PVN, this effect does not involve alteration of ACe-CRH expression.

Potential mechanisms for enhancement of hippocampal GR expression

The current study demonstrated an early reduction of hypothalamic CRH expression with subsequent changes in the stress response that are followed by increased hippocampal GR-mRNA levels. The mechanisms mediating this chain of events may be divided into two general alternatives: First, reduced hypothalamic CRH may influence hippocampal GRs directly, via a neuroendocrine feedback loop. Thus, diminished CRH release during stress, with consequent reduction of glucocorticoid secretion, disinhibits (up-regulates) hippocampal GR expression (13, 37). This molecular cascade leads to a new steady-state, consisting of the reduced HPA tone observed in adult rats handled during early-life. Alternatively, early-life handling/sensory input may influence as yet unknown targets in the stress-integration circuit, via complex multineurotransmitter mechanisms. This primary modulation would then alter hippocampal GR and hypothalamic CRH with different velocities or at different time-points. The actual interval, days 23–45, when GR-mRNA up-regulation occurs also coincides with puberty. Thus, potential interactions of these processes with sex hormones, or their down-stream effects, may be considered.

Reduced stress response of handled rats arises subsequent to down-regulation of CRH expression, but precedes changes in hippocampal GR-mRNA levels

Although basal ACTH and CORT levels of the two groups did not differ, the magnitude of hormonal stress response of the handled group was smaller than that of the undisturbed one, starting on postnatal day 23. The emergence of this hormonal difference before up-regulation of hippocampal GR expression indicates that the latter is unlikely to play a mechanistic role in handling-related reduction of the stress response. Indeed, the data are consistent with an alternative scenario in which diminished levels of circulating glucocorticoids lead to enhanced, disinhibited hippocampal GR expression. An apparent reduction of the overall magnitude of the stress response of handled rats was observed between days 23 and 45. Whether the restraint challenge was not as powerful a stressor on day 45, or whether the up-regulation of GR-mRNA—present by day 45— contributed to this observation, cannot be resolved in the current study. Baseline ACTH levels during the two ages did not differ and are consistent with levels found using the INCSTAR Corp. assay.

In summary, this study centered on the hypothesis that determination of early and persistent molecular changes following neonatal handling would provide important clues about the mechanism(s) by which neonatal experience influences the hormonal stress-response long-term. The results of this study demonstrate that regulation of CRH expression is an early and sustained event in the molecular cascade resulting from neonatal handling. In addition, these data indicate that CRH regulation may provide an important target for clinically relevant intervention in the processes by which early-life experience modulates adult responses to subsequent stress.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michele Hinojosa for excellent editorial assistance.

This work was supported by NIH Grants NS-28912 and NS-39307.

References

- 1.Levine S, Lewis GW. Critical period for the effects of infantile experience on the maturation of a stress response. Science. 1959;129:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.129.3340.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess JL, Denenberg VH, Zarrow M, Peiffer WD. Modification of the corticosterone response curve as a function of handling in infancy. Physiol Behav. 1969;4:102–109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine S. The psychoendocrinology of stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;697:61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meaney MJ, Diorio J, Francis D, Widdowson J, LaPlante P, Caldji C, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Plotsky PM. Early environmental regulation of forebrain glucocorticoid receptor gene expression: implications for adrenocortical responses to stress. Dev Neurosci. 1996;18:49–72. doi: 10.1159/000111395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heim C, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. Persistent changes in corticotropin-releasing factor systems due to early life stress: relationship to the pathophysiology of major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu D, Diorio j, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress. Science. 1997;277:1659–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldji C, Tannenbaum B, Sharma S, Francis D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5335–5340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis DD, Meaney MJ. Maternal care and the development of stress responses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:128–134. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand M, Sarrieau A, Aguerre S, Mormède P, Chaouloff F. Differential effects of neonatal handling on anxiety, corticosterone response to stress, and hippocampal glucocorticoid and serotonin (5-HT)2A receptors in Lewis rats. Psychoendocrinology. 1998;23:323–335. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Early, postnatal experience alters hypothalamic corticotropin- releasing factor (CRF) mRNA, median eminence CRF content and stress-induced release in adult rats. Mol Brain Res. 1993;18:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90189-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viau V, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to stress in handled and non-handled rats: Differences in stress-induced plasma ACTH secretion are not dependent upon increased corticosterone levels. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1097–1105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01097.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman JP, Patel PD, Akil H, Watson SJ. Localization and regulation of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor messenger RNAs in the hippocampal formation of the rat. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:3072–3082. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-11-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi SJ, Baram TZ. Corticotropin-releasing hormone mediates the response to cold stress in the neonatal rat without compensatory enhancement of the peptide's gene expression. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2364–2368. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MA, Kim SY, Van Oers HJJ, Levine S. Maternal deprivation and stress induce immediate early genes in the infant rat brain. Endocrinology. 1997;128:4622–4628. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatalski CG, Guirguis C, Baram TZ. Corticotropin releasing factor mRNA expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and the central nucleus of the amygdala is modulated by repeated acute stress in the immature rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:663–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meaney MJ, Aitken DH. The effects of early postnatal handling on hippocampal gluco-corticoid receptor concentration: temporal parameters. Dev Brain Res. 1985;22:301–304. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts AG, Swanson LW. Diurnal variation in the content of preprocor-ticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acids in the hypothalamic PVN of rats of both sexes as measured by in situ hybridization. Endocrinology. 1989;125:1734–1738. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-3-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akana SF, Scribner KA, Bradbury MJ, Strack AM, Walker CD, Dallman MF. Feedback sensitivity of the rat hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis and its capacity to adjust to exogenous corticosterone. Endocrinology. 1992;131:585–594. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.2.1322275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meaney MJ, Aitken DH, Sharma S, Viau V, Sarrieau A. Postnatal handling increases hippocampal type II, glucocorticoid receptors and enhances adrenocortical negative-feedback efficacy in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;51:597–604. doi: 10.1159/000125287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avishai-Eliner S, Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Hatalski CG, Schultz L, Baram TZ. Handling induced downregulation of hypothalamic corticotropin releasing factor-mRNA precedes changes in hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor-mRNA. Soc Neurosci Abst. 1997;27:39212. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avishai-Eliner S, Yi SJ, Newth CJL, Baram TZ. Effects of maternal and sibling deprivation on basal and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal components in the infant rat. Neurosci Lett. 1995;192:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11606-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherwood NM, Timiras PS. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Developing Rat Brain. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avishai-Eliner S, Hatalski CG, Tabachnik E, Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Baram TZ. Differential regulation of glucocorticoid receptor messenger RNA by maternal deprivation in immature rat hypothalamus and limbic regions. Dev Brain Res. 1999;114:265–268. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Avishai-Eliner S, Hatalski CG, Baram TZ. Differential regulation of the expression of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 (CRF2) in hypothalamus and amygdala of the immature rat by sensory input and food intake. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3982–3991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03982.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi SJ, Masters JN, Baram TZ. Glucocorticoid receptor mRNA ontogeny in the fetal and postnatal rat forebrain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:385–393. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Eekelen JAM, Bohn MC, De Kloet ER. Postnatal ontogeny of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor gene expression in regions of the rat tel- and diencephalon. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;61:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90111-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vázquez DM. Stress and developing limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:663–667. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Donnell D, Larocque S, Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Postnatal handling alters glucocorticoid, but not mineralocorticoid messenger RNA expression in the hippocampus of adult rats. Mol Brain Res. 1994;26:242–248. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatnagar S, Meaney MJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in chronic intermittently cold-stressed neonatally handled and non-handled rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1995;7:97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker C-D, Dallman MF. Neonatal facilitation of stress-induced adrenocorticotropin secretion by prior stress: evidence for increased central drive to the pituitary. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1101–1107. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.8382596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Merlo Pich E, Britton KT, Koob GF. The role of CRF in behavioral aspects of stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;771:92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivier J, Spiess J, Vale W. Characterization of rat hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4851–4855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baram TZ, Yi SJ, Avishai-Eliner S, Schultz L. Developmental neurobiology of the stress-response: multi-level regulation of corticotropin releasing hormone function. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;814:404–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson LW, Simmons DM. Differential steroid hormone and neural influences on peptide mRNA levels in CRH cells of the paraventricular nucleus: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285:413–435. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peiffer A, Lapointe B, Barden N. Hormonal regulation of type II glucocorticoid receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1991;129:2166–2174. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-4-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spencer RL, Miller AH, Stein M, McEwen BS. Corticosterone regulation of type I and type II adrenal steroid receptors in brain, pituitary, and immune tissue. Brain Res. 1991;549:236–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dallman MF, Akana SF, Cascio CS, Darlington DN, Jacobson L, Levin N. Regulation of ACTH secretion: variations on a theme of B. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1987;43:113–173. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571143-2.50010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herman JP, Schäfer MK, Young EA, Thompson R, Douglass J, Akil H, Watson SJ. Evidence for hippocampal regulation of neuroendocrine neurons of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3072–3082. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-09-03072.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oitzl MS, Van Haarst AD, De Kloet ER. Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses controlled by the concerted action of central mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22:S87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Donnell D, Francis D, Weaver S, Meaney MJ. Effects of adrenalectomy and corticosterone replacement on glucocorticoid receptor levels in rat brain tissue: a comparison between Western blotting and receptor binding assays. Brain Res. 1995;687:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00479-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plotsky PM. Pathways to the secretion of adrenocorticotropin: a view from the portal. J Neuroendocrinol. 1991;3:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1991.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitkänen A, Savander V, LeDoux JE. Organization of intra-amygdaloid circuitries in the rat: an emerging framework for understanding functions of the amygdala. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:517–523. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrovich GD, Swanson LW. Projections from the lateral part of the central amygdalar nucleus to the postulated fear conditioning circuit. Brain Res. 1997;763:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia HG, Rao ZR, Shi JW. An indirect projection from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the central nucleus of the amygdala via the parabrachial nucleus in the rat: a light and electron microscopic study. Brain Res. 1994;663:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhatnagar S, Dallman M. Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience. 1998;84:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Organization of the projections from the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a Phaseolus vulgarisleucoagglutinin study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348:41–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suemaru S, Darlington DN, Akana SF, Cascio CS, Dallman MF. Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions inhibit corticosteroid feedback regulation of basal ACTH during the trough of the circadian rhythm. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:453–463. doi: 10.1159/000126868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;35:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss JM, Stout JC, Aaron MF, Quan N, Owens MJ, Butler PD, Nemeroff CB. Depression and anxiety: role of the locus coeruleus and corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35:561–572. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunningham ET, Sawchenko PE. Anatomical specificity of noradrenergic inputs to the para-ventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the rat hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1988;274:60–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.902740107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plotsky PM, Cunningham ET, Widmaier EP. Catecholaminergic modulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:437–458. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-4-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itoi K, Seasholtz AF, Watson SJ. Cellular and extracellular regulatory mechanisms of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocr J. 1998;45:13–33. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.45.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Day HE, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Expression of α1b adrenoreceptor mRNA in corticotropin-releasing hormone-containing cells of the rat hypothalamus and its regulation by corticosterone. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10098–10106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10098.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:425–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalin NH, Takahashi LK, Chen FL. Restraint stress increases corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA content in the amygdala and paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res. 1994;656:182–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu D, Caldji C, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Influence of neonatal rearing conditions on stress-Induced adrenocorticotropin responses and norepinephrine release in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibbs DM, Vale W. Effect of the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine on corticotropin-releasing factor and vasopressin secretion into hypophysial portal blood. Brain Res. 1983;280:176–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kageyama K, Tozawa F, Horiba N, Watanobe H, Suda T. Serotonin stimulates corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of conscious rats. Neurosci lett. 1998;243:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beaulieu S, Pelletier G, Vaudry H, Barden N. Influence of the central nucleus of the amygdala on the content of corticotropin-releasing factor in the median eminence. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;49:255–261. doi: 10.1159/000125125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gray TS, Bingaman EW. The amygdala: corticotropin-releasing factor, steroids, and stress. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:155–168. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]