Transcriptional regulation by the numbers: models (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Oct 27.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005 Apr;15(2):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.02.007

Abstract

The expression of genes is regularly characterized with respect to how much, how fast, when and where. Such quantitative data demands quantitative models. Thermodynamic models are based on the assumption that the level of gene expression is proportional to the equilibrium probability that RNA polymerase (RNAP) is bound to the promoter of interest. Statistical mechanics provides a framework for computing these probabilities. Within this framework, interactions of activators, repressors, helper molecules and RNAP are described by a single function, the ‘regulation factor’. This analysis culminates in an expression for the probability of RNA polymerase binding at the promoter of interest as a function of the number of regulatory proteins in the cell.

Introduction

The biological literature on the regulation and expression of genes is, with increasing frequency, couched in the language of numbers. Four key ways in which gene expression is characterized quantitatively are through measurement of: (i) the level of expression relative to some reference value; (ii) how fast a given gene is expressed after induction; (iii) the precise relative timing of expression of different genes; and (iv) the spatial location of expression. In the first section of this review we revisit particular examples of such measurements in the bacterial setting. These provide the motivation for the models that form the main substance of this and the companion article [1••]. Through much of these reviews we call attention to particular revealing case studies rather that giving a thorough coverage of the literature.

How much, when and where?

One class of particularly well-characterized examples of gene expression levels includes cases associated with bacterial metabolism and the infection of bacteria by phage [2••,3]. This group will serve as the centerpiece of this and the companion article. In the classic case of the lac operon, several beautiful measurements have been taken. These characterize the extent to which the genes are repressed as a function of the strength of the operators, their spacing and the number of repressor molecules [4–6]. Similar measurements have been made for other genes implicated in bacterial metabolism, in addition to those tied to the decision between the lytic and lysogenic pathways after infection of Escherichia coli by phage lambda [7–11]. A second way by which the regulatory status of a given system is quantified is by measuring when genes of interest are being expressed. The list of examples is long and inspiring, and several representative case studies can be found in the literature [12–14]. A third way in which an increasingly quantitative picture of gene expression is emerging is based on the ability to make precise statements about the spatial location of the expression of different genes. Here, too, the number of different examples that can be mustered to prove the general point is staggering [15–17]. The key point of these examples is to note the growing pressure head of quantitative in vivo data, which calls for more than a cartoon-level description of expression.

The physicochemical modeling of the type of quantitative data described above is still in its infancy. One class of models, which will serve as the basis of this article, comprises the so-called ‘thermodynamic models’ [18–20]. The conceptual basis of this class of models is the idea that the expression level of the gene of interest can be deduced by examining the equilibrium probabilities that the DNA associated with that gene is occupied by various molecules — these include RNAP and a battery of transcription factors (TFs) such as repressors and activators. There is a long-standing tradition of using these ideas to unravel the dynamics of gene expression systems — particularly important examples being associated with the famed lac operon and phage lambda systems [18,21–26]. Importantly, the thermodynamic models can serve as input to more general chemical kinetic models.

The key aim of this and the accompanying article [1••] is to show how the thermodynamic models yield a general conceptual picture of regulation using what we call the ‘regulation factor’ (see Glossary). Such arguments are useful because they enable direct comparison with quantitative experiments, such as those discussed above. The purpose of models is not just to ‘fit the data’ (although such fits can reveal which mechanisms are operative) but also to provide a conceptual scheme for understanding measurements and, more importantly, for suggesting new experiments. It is also worth noting that when such models fall short it provides an opportunity to find out why and learn something new.

This article is, to a large extent, pedagogical and aims to demonstrate how a microscopic picture of the various states of the gene of interest can be mathematized using statistical mechanics. The companion article [1••] is built around the analysis of case-studies in bacterial transcription and centers specifically on how the activity of a given promoter is altered (the ‘fold-change’ [see Glossary] in promoter activity) by the presence of transcription factors.

Thermodynamic models of gene regulation: the regulation factor

The fundamental tenet of the thermodynamic models for gene regulation is that we can replace the difficult task of computing the level of gene expression, as measured by the concentration of gene product ([protein]), with the more tractable question of the probability (_p_bound) that RNAP occupies the promoter of interest. More precisely, these models are founded on the idea that the instantaneous disposition of the gene of interest can be established from the probability that various molecules —RNAP, activators, repressors and inducers — are bound to their relevant targets.

Such models are based on a variety of different assumptions, all of which can and should be evaluated critically. Perhaps the most glaring assumption is that of equilibrium itself. This assumption can be examined quantitatively on the basis of the relative rates of transcription factor binding, RNAP binding, open complex formation, transcript formation and translation itself. For example, if the rate for open complex formation is much smaller than the rates for RNAP binding and unbinding from the promoter, then the probability of finding the polymerase on the promoter will be given by its equilibrium value. A second key assumption of this class of models is the idea that the probability of promoter occupancy by RNAP is simply proportional to the level of expression of a given gene. The difficulty lies in the fact that there are several different mechanisms that can intervene between RNAP binding and the existence of a functional gene product. Despite these caveats, we argue that this class of models is both instructive and predictive and, in those cases where the models are found wanting, provides an opportunity to learn something.

In this review, we first analyse the probability that RNAP will be bound at the promoter of interest in the absence of any activators or repressors. This is followed by cases of increasing complexity that involve batteries of transcription factors. Although our preliminary discussion is focused on the statistical mechanics of polymerase binding, the framework is the same for generic protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions. For the purposes of this review, we make the simplified assumption that the key molecular players (RNAP and TFs) are bound to the DNA either specifically or non-specifically. This question has been addressed in the context of the λ switch [27], for the lac repressor [21,28] and for RNAP [29]. Stated differently, as a simplification, we will ignore the contribution of ‘free’ polymerase in the cytoplasm, in addition to those RNAP molecules that are engaged in transcription on other promoters. Relaxing this assumption has no effect on the framework developed below. Hence, to evaluate the probability of promoter occupancy in this simple model, the reservoir of RNAPs will be the non-specifically bound molecules (as shown in Figure 1a).

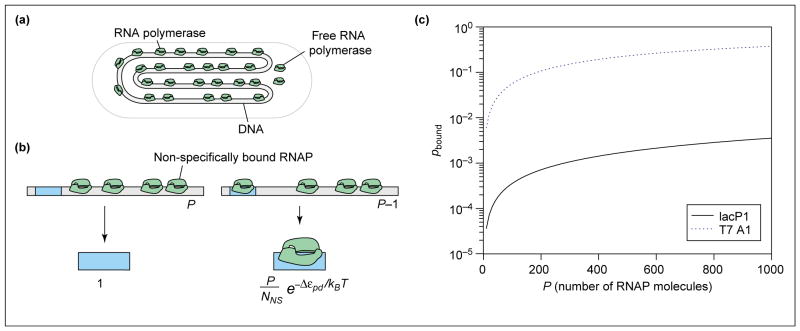

Figure 1.

Probability of promoter occupancy (a) Schematic showing how, in the simple model, the DNA molecule serves as a reservoir for the RNAP molecules, almost all of which are bound to DNA. (b) Illustration of the states of the promoter – either with RNAP not bound or bound and the remaining polymerase molecules distributed among the non-specific sites. The statistical weights associated with these different states of promoter occupancy are also shown. (c) Probability of binding of RNAP to promoter as a function of the number of RNAP molecules for two different promoters. We assume the number of non-specific sites is NNS = 5 × 106, and calculate the binding energy difference using the simple relation Δεpd=kBTln(KpdS/KpdNS), where the equilibrium dissociation constants for specific binding (KpdS) and non-specific binding (KpdNS) are taken from in vitro measurements. In particular, making the simplest assumption that the genomic background for RNAP is given only by the non-specific binding of RNAP with DNA, we take KpdNS=10000nM [37], for the lac promoter KpdS=550nM [38] and for the T7 promoter, KpdS=3nM [39]. For the lac promoter, this results in Δ_εpd_ = −2.9_kBT_ and for the T7 promoter, Δ_εpd_ = −8.1_kBT_.

To evaluate the probability of polymerase binding (pbound) we must sum the Boltzmann weights (see Glossary) over all possible states of P polymerase molecules on DNA [30••,31••]. P is the effective number of RNAP molecules available for binding to the promoter. Estimating this number in vivo is fraught with difficulty because many RNAPs are engaged in transcription at any given time and, as such, are not available for binding. Fortunately, this problem is avoided when calculating the fold-change for all the cases of interest, as we do in the accompanying paper [1••]. This is because, in these cases, the absence of activators results in a very small pbound value and so P drops out of the problem.

We calculate pbound by considering the distribution of P RNAP on the non-specific sites (NNS), which make up the genome itself, and a single promoter. Then we distinguish two classes of outcomes (shown in Figure 1b): all P RNAP molecules bound non-specifically, or one RNAP bound to the promoter and P_−1 RNAP bound non-specifically. Next, we count the number of different ways that these outcomes can be realized. Once these states have been enumerated, we weight each of them according to the Boltzmann law: if ε is the energy of a state, its statistical weight is exp(−ε/kBT_). Finally, to compute the probability of promoter occupancy, we construct the ratio of the sum of the weights for the favorable outcome (i.e. promoter occupied) to the sum over all of the weights.

As noted above, this simple model includes two broad classes of microscopic outcomes: (i) those in which all P polymerase molecules are distributed among the non-specific sites, and (ii) those in which the promoter is occupied and the remaining _P_−1 polymerase molecules are distributed among the non-specific sites. To evaluate the probabilities of these two eventualities we need to know the number of different ways that each outcome can be realized. The statistical question of how many ways there are to distribute P polymerase molecules among NNS non-specific sites on the DNA is a classic problem in combinatorics, and the result is

The overall statistical weight of these states is based not just on how many of them there are but also on their Boltzmann weights according to

| Z(P)︸statisticalweight-promoterunoccupied=NNS!P!(NNS-P)!︸numberofarrangements×e-PεpdNS/kBT︸Boltzmannweight, | (1) |

|---|

where εpdNS is an energy that represents the average binding energy of RNAP to the genomic background. The correct treatment of the genomic background requires explicit consideration of the distribution of binding energies of RNAP, and TFs, to different sites — both specific and non-specific — on the DNA. The question of how to treat this problem more generally than the simpleminded treatment given here can be found in [32,33]. The total statistical weight can now be written as

| Ztot(P)︸totalstatisticalweight=Z(P)︸promoterunoccupied+Z(P-1)e-εpdS/kBT︸RNAPonpromoter, | (2) |

|---|

where εpdS is the binding energy for RNAP on the promoter (the S stands for ‘specific’). The states and corresponding weights, normalized by the weight of the promoter-unoccupied states, Z(P), are shown in Figure 1b.

To find the probability of RNAP being bound to the promoter of interest, we calculate

| pbound=Z(P-1)e-εpdS/kBTZtot(P). | (3) |

|---|

Note that the numerator in this case is the statistical weight of all microscopic states in which the promoter is occupied, and the denominator is the statistical weight of all microscopic states. If we now divide top and bottom by Z(P-1)e-εpdS/kBT and use the functional form given in Equation 1, the probability of promoter occupancy is given by the simple form

| pbound=11+NNSPeΔεpd/kBT, | (4) |

|---|

where we have introduced the notation Δεpd=εpdS-εpdNS [34]. To obtain the last equation we made the simplifying assumption that P ≪ NNS. The results computed above can be depicted in graphical form (as shown in Figure 1c) by plotting the probability of promoter occupancy as a function of the number of RNAP molecules for two different promoters. For this particular case we have used several rough estimates, explained in the figure legend, concerning the binding energies of RNAP molecules to specific and non-specific sites on the DNA in a typical bacterial cell. One interesting speculation is that the high probability of RNAP occupancy for the T7 promoter, even in the absence of transcription factors, could be related to the infection mechanism of T7 phage [35]. In contrast, it is also interesting to note the very low probability of occupancy of the lac promoter in this simple model in the absence of activation. We view Equation 4 as characterizing the ‘basal’ transcription rate in this simple model. In light of this result, the key conceptual outcome of the remainder of this review is the idea that the presence of transcription factors (activators and repressors, etc.) has the effect of altering Equation 4 to the simple form

| pbound=11+NNSPFregeΔεpd/kBT, | (5) |

|---|

where we introduce the regulation factor, Freg. The regulation factor should be seen as describing an effective increase (for Freg > 1) or decrease (for Freg < 1) of the number of RNAP molecules that are available to bind the promoter.

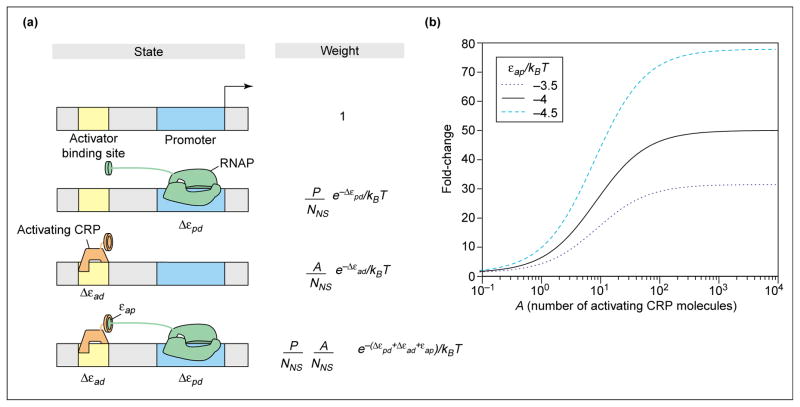

To illustrate precisely the idea of the regulation factor, we show how activators recruit [3] RNAP to the promoter of interest. The recruitment concept is illustrated in schematic form in Figure 2a, where it is seen that the activator molecule recruits the polymerase through favorable contacts characterized by an adhesive energy, εap The point of the schematic is to show how the various states of occupancy of the promoter and activator binding site can be assigned Boltzmann weights, which can then be used to compute their probabilities.

Figure 2.

Statistical mechanics of recruitment (a) Schematic showing the relationship between the various states of the promoter and its regulatory region, and their corresponding weights within the statistical mechanics framework. (b) Fold-change in promoter activity as a function of the number of activated (inducer-bound) CRP molecules, according to Equations 5 and 8, for different values of the adhesive interaction energy between activator and RNAP. As in Figure 1, Δεad=kBTln(KadS/KadNS), with KadNS=10000nM [40] and KadS=0.02nM [41]. These in vitro numbers are chosen as a representative example to provide intuition for the action of activators. Applications to in vivo experiments are given in the accompanying paper [1••]. Several different representative values of the adhesive interaction _ε_ad that are consistent with measured activation are chosen to illustrate how activation depends upon this parameter.

Once again, the first step in our analysis is to determine the total statistical weight. This is obtained by summing the Boltzmann weights of all of the eventualities associated with the activators and polymerase molecules being distributed on the DNA (both non-specific sites and the promoter). As seen in Figure 2a, there are four classes of outcomes: (i) both the activator site and promoter unoccupied; (ii) just the promoter occupied by polymerase; (iii) just the activator site occupied by activator; and (iv) both of the specific sites occupied. This is represented mathematically as

| Ztot(P,A)=Z(P,A)︸emptysites+Z(P-1,A)e-εpdS/kBT︸RNAPonpromoter+Z(P,A-1)e-εadS/kBT︸activatoronspecificsite+Z(P-1,A-1)e-(εpdS+εadS+εpd)/kBT︸RNAPandactivatorboundspecifically, | (6) |

|---|

where the statistical weight for P polymerase molecules and A activator molecules distributed among NNS non-specific sites is given by

| Z(P,A)=NNS!P!A!(NNS-P-A)!︸numberofarrangements×e-PεpdNS/kBTe-AεadNS/kBT︸weightofeachstate | (7) |

|---|

In Figure 2a the weights of the four states are normalized by the weight of the empty state Z(P,A). In Equation 7 we use the notation εxd to characterize the binding energy of molecule X to DNA, and superscripts S and NS to signify specific or non-specific binding, respectively. Δεxd=εxdS-εxdNS is the difference between the two. For the purposes of this simple model we have assumed that the reservoir for the activator molecules is the genomic DNA, although there is strong evidence that, in the case of the lac operon, many of the activators (cAMP receptor proteins; CRPs) are actually in the cytoplasm [36]. In contrast, as will be seen in the following paper [1••], in our actual applications of thermodynamic models to real operons, the question of whether the reservoir is non-specific DNA or the cytoplasm never arises.

As usual, to compute the probability of interest, we construct the ratio of the sum of weights for all those outcomes that are favorable (i.e. polymerase bound to the promoter) to the sum of weights over the total set of outcomes Ztot(P,A). This results in a value of _p_bound that adopts precisely the form described in Equation 5. The regulation factor, Freg (A), is given by

| Freg(A)=1+ANNSe-Δεad/kBTe-εap/kBT1+ANNSe-Δεad/kBT, | (8) |

|---|

where we have made the additional assumption that NNS ≫ P, A. Note that if the adhesive interaction between polymerase and activator goes to zero, the regulation factor itself goes to unity. Furthermore, for negative values of this adhesive interaction (i.e. activator and polymerase like to be near each other) the regulation factor is greater than one, which translates into an apparent increase in the number of polymerase molecules available for binding to the promoter. This claim can be seen more clearly if we define the fold-change in promoter activity as the ratio of the probability that RNAP is bound in the presence of transcription factors to the probability that it is bound in the absence of transcription factors: fold-change = pbound(P, A)/pbound(P, A = 0). The fold-change is plotted in Figure 2b for typical values of the adhesive interaction εap and the other binding parameters, for the simple model in which the reservoir for CRP is assumed to be non-specific DNA.

Similar arguments can be made for the action of repressor molecules. Consider repression by R repressor molecules that can bind to an operator (with energy εrdS) that overlaps with the promoter. By enumerating the different states with their associated weights in a way similar to that used in Figure 2a and noting that the state where both the repressor and RNAP bind to their sites is not allowed, we can again derive the form for promoter occupation, Equation 5, but this time with the regulation factor,

| Freg(R)=11+RNNSe-Δεrd/kBT. | (9) |

|---|

The above scheme can be extended further to describe co-regulation by two or more activators and/or repressors. For example, in the case of activation considered above, if the binding of the activator to its operator site is assisted itself by a helper protein, which might bind to an adjacent site [1••], then the regulation factor still has the form given in Equation 8 but with the number of activators, A, replaced by an effective number of activators

| A′=A1+HNNSe-Δεhd/kBTe-εha/kBT1+HNNSe-Δεhd/kBT. | (10) |

|---|

Note that the multiplicative factor in Equation 10 has the same form as in Equation 8 except that now the number of helper molecules, H, appears in the expression, and the interaction energy εha refers to that between the helper molecules and activators. In fact, this is the generic expression describing the recruitment of one DNA-binding protein by another, and it is not limited to activator–RNAP recruitment.

The introduction of the regulation factor enables a discussion of various regulatory motifs in a unified way, as made explicit by Table 1. These examples will be discussed in the context of particular bacterial gene-regulatory systems in the ensuing paper. The main point captured by this table is that the conceptual picture of thermodynamic models is identical regardless of regulatory motif and involves summing all of the relevant states. It culminates in the regulation factor which, as will be shown in the companion [1••], is equal to the measurable fold-change of promoter activity.

Table 1.

Regulation factors for several different regulatory motifs.

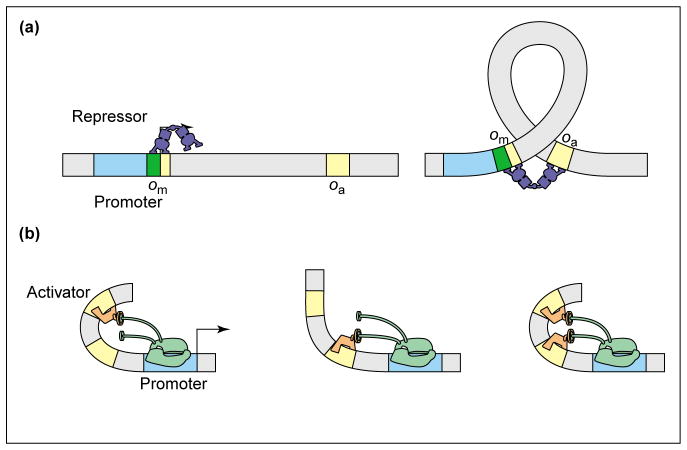

As a final example, we consider the way in which DNA looping can play a role in dictating the regulation factor. Indeed, recent work by Vilar and Leibler [31••] and Vilar and Saiz [42••] and others [25,43] has shown how the thermodynamic models can be applied to regulatory control by looping. In the accompanying paper [1••], we apply these ideas to the particular question of how such regulation depends upon the distance between the two binding sites, but content ourselves here with a discussion of the conceptual basis. Two distinct looping scenarios are shown in Figure 3. In case (a), a repressor molecule, which can bind to two distinct regions on the DNA, loops out the intervening region. The classic example of this mode of action is the Lac repressor. In case (b), one protein, such as CRP, favorably bends the DNA so that a second activator can contact RNAP, although paying a lower free energy cost than it would if it were acting alone. In both cases, the free energy cost associated with making a DNA loop is outweighed by the benefit of additional binding energy between the repressor and DNA [case (a)] and between the activator and RNAP [case (b)].

Figure 3.

DNA bending in transcription regulation. (a) DNA looping enables Lac repressor to bind to the main and the auxiliary operators simultaneously, thereby increasing the weight of the states in which the promoter is unoccupied. This leads to stronger repression than in the single operator case. (b) DNA bending by the activator leads to cooperative binding of the two activators because the free energy cost of bending is paid only once. This leads to a boost in activation above that provided by independent binding of the two activators [45].

In summary, the statistical mechanical framework described here can be used to consider several different regulatory motifs [11,26,30••,32,33,44], as showcased in Table 1. In each of the cases considered in the table, the probability of promoter occupancy is given by Equation 5, with the sole change from one case to the next being the form adopted by the regulation factor itself.

Conclusions and future prospects

We argue that as a result of the increasingly quantitative character of data on gene expression there is a corresponding need for predictive models. We have reviewed a series of general arguments about the way in which batteries of transcription factors work in generic ways to mediate transcriptional regulation. The models described here result in several important classes of predictions. The application of these ideas to particular bacterial scenarios forms the substance of the second article [1••].

Though ideas like those presented here have the potential to serve as a quantitative framework for thinking about transcriptional regulation, there are several outstanding issues. Some especially troubling features of these models are: (i) what are the precise conditions under which equilibrium assumptions are acceptable? (ii) When can the probability of RNAP binding at a promoter serve as a surrogate for gene expression itself? (iii) What is the role of fluctuations? (iv) These models pretend that the basal transcription apparatus is a single molecule that interacts with transcription factors, whereas the transcription apparatus is a complex that is itself probably subject to recruitment for its assembly. Despite these concerns, our view is that thermodynamic models have long demonstrated their utility and it will be of great interest to carefully explore their consequences experimentally. Case studies using the thermodynamic models are reviewed in the accompanying paper [1••].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to several people for explaining their work and that of others to us, including Michael Welte, Jon Widom, Mark Ptashne, Phil Nelson, Jeff Gelles, Ann Hochschild, Mitch Lewis, Bob Schleif, Michael Elowitz, Paul Wiggins, Mandar Inamdar, Scott Fraser, Richard Ebright, Eric Davidson and Titus Brown. Of course, any errors in interpretation are our own. We are also thankful to Nigel Orme for his extensive contributions to the figures in this paper. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the NIH Director’s Pioneer Award (RP), NSF through a NIRT award (RP), DMR9984471 (JK) and DMR0403997 (JK). JK is a Cottrell Scholar of Research Corporation. UG acknowledges an ‘Emmy Noether’ research grant from the DFG. TH is grateful to financial support by the NSF through grants 0211308, 0216576 and 0225630.

Glossary

Boltzmann factor

For a given state of a thermal system, the Boltzmann factor is the exponential of minus its energy, measured in units of kBT. The ratio of equilibrium probabilities for any two states is given by the ratio of their Boltzmann factors

Partition function

The sum of the Boltzmann factors for all the states available to a thermal system. The equilibrium probability of observing a state of the system is its Boltzmann factor divided by the partition function

Regulation factor

The effective change of the number of RNA polymerases available for binding to the promoter, resulting from the action of transcription factors. The regulation factor is a function of transcription factor concentrations, operator distances, protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions. It is smaller than one for repression, and larger than one for activation

Fold-change

The ratio of gene expression (e.g. transcription rate) in the presence and absence of transcription factors. Within the thermodynamic model, this fold-change is given by the ratio of occupation probability of the promoter of interest by the RNA polymerase holoenzyme, in the presence and absence of transcription factors. For weak promoters that control the transcription of typical bacterial genes, the fold-change in gene expression is given approximately by the regulation factor

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1••.Bintu L, Buchler NE, Garcia HG, Gerland U, Hwa T, Kondev J, Kuhlman T, Phillips R. Transcriptional regulation by the numbers: applications. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.02.006. The companion paper to this article applies the thermodynamic models to a host of different promoters in bacteria and shows the regulation factor in action. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Ptashne M. A Genetic Switch. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2004. This book is a reprinting of Ptashne’s classic, with a special additional chapter that examines recent developments concerning regulation of the life cycle of phage lambda. One of the key recent developments is an appreciation of the role of DNA looping in this system. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ptashne M, Gann A. Genes and Signals. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellomy GR, Mossing MC, Record MT. Physical properties of DNA in vivo as probed by the length dependence of the lac operator looping process. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3900–3906. doi: 10.1021/bi00411a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oehler S, Amouyal M, Kolkhof P, von Wilcken-Bergmann B, Müller-Hill B. Quality and position of the three lac operators of E. coli define efficiency of repression. EMBO J. 1994;13:3348–3355. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller J, Oehler S, Müller-Hill B. Repression of lac promoter as a function of distance, phase and quality of an auxiliary lac operator. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:21–29. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D-H, Schleif RF. In vivo DNA loops in araCBAD size limits and helical repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:476–480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis DEA, Adhya S. In vitro repression of the gal promoters by GalR and HU depends on the proper helical phasing of the two operators. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2498–2504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochschild A, Ptashne M. Interaction at a distance between λ repressors disrupts gene activation. Nature. 1988;336:353–357. doi: 10.1038/336353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joung JK, Koepp DM, Hochschild A. Synergistic activation of transcription by bacteriophage λ cI protein and E. coli cAMP receptor protein. Science. 1994;265:1863–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.8091212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setty Y, Mayo AE, Surette MG, Alon U. Detailed map of a cis-regulatory input function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7702–7707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalir S, McCluer J, Pabbaraju K, Southward C, Ronen M, Leibler S, Surette MG, Alon U. Ordering genes in a flagella pathway by analysis of expression kinetics from living bacteria. Science. 2001;292:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1058758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laub MT, McAdams HH, Feldblyum T, Fraser CM, Shapiro L. Global analysis of the genetic network controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Science. 2000;290:2144–2148. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbeitman JN, Furlong EEM, Imam F, Johnson E, Null BH, Baker BS, Krasnow MA, Scott MP, Davis RW, White KP. Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2002;297:2270–2275. doi: 10.1126/science.1072152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson EH. Genomic Regulatory Systems. Academic Press; San Diego, California: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carroll SB, Grenier JK, Weatherbee SD. From DNA to Diversity. Blackwell Science; Malden, Massachusetts: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Small S, Blair A, Levine M. Regulation of even-skipped stripe 2 in the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1992;11:4047–4057. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackers GK, Johnson AD, Shea MA. Quantitative model for gene regulation by λ phage repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1129–1133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shea MA, Ackers GK. The OR control system of bacteriophage lambda, a physical-chemical model for gene regulation. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:211–230. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill TL. Cooperativity Theory in Biochemistry. Springer-Verlag; New York, New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Hippel PH, Revzin A, Gross CA, Wang AC. Non-specific DNA binding of genome regulating proteins as a biological control mechanism: 1. The lac operon: equilibrium aspects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4808–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.12.4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law SM, Bellomy GR, Schlax PJ, Record MT. In vivo thermodynamic analysis of repression with and without looping in lac constructs. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:161–173. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ben-Naim A. Cooperativity in binding of proteins to DNA. J Chem Phys. 1997;107:10242–10252. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Naim A. Cooperativity in binding of proteins to DNA. II. Binding of bacteriophage λ repressor to the left and right operators. J Chem Phys. 1998;108:6937–6946. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodd IB, Shearwin KE, Perkins AJ, Burr T, Hochschild A, Egan JB. Cooperativity in the long-range gene regulation by the λ cI repressor. Genes Dev. 2004;18:344–354. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakk A, Metzler R, Sneppen K. Sensitivity of OR in phage λ. Biophys J. 2004;86:58–66. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74083-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakk A, Metzler R. In vivo non-specific binding of λ CI and Cro repressors is significant. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:66–68. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kao-Huang Y, Revzin A, Butler AP, O’Conner P, Noble DW, von Hippel PH. Nonspecific DNA binding of genome-regulating proteins as a biological control mechanism: measurement of DNA-bound Escherichia coli lac repressor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4228–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rünzi W, Matzura H. In vivo distribution of ribonucleic acid polymerase between cytoplasm and nucleoid in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:1237–1239. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.1237-1239.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Buchler NE, Gerland U, Hwa T. On schemes of combinatorial transcription logic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5136–5141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930314100. The supporting text of this paper shows how to implement models like those described here in statistical mechanics language and applies it to construct various logical states. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31••.Vilar JMG, Leibler S. DNA looping and physical constraints on transcriptional regulation. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:981–989. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00764-2. The authors provide an explicit calculation of repression in the lac operon and show that this results in a consistent definition of the looping free energy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerland U, Moroz JD, Hwa T. Physical constraints and functional characteristics of transcription factor–DNA interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12015–12020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192693599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sengupta AM, Djordjevic M, Shraiman BI. Specificity and robustness in transcription control networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2072–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022388499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruinsma RF. Physics of Protein–DNA Interaction. In: Flyvbjerg H, Julicher F, Ormos P, David F, editors. Physics of Bio-molecules and Cells. Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molineux IJ. No syringes please, ejection of phage T7 DNA from the virion is enzyme driven. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook DI, Revzin A. Intracellular localization of catabolite activator protein of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1980;141:1279–1283. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.3.1279-1283.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Record MT, Reznikoff WS, Craig ML, McQuade KL, Schlax PJ. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (σ70) promoters and the kinetics of the steps of transcription initiation. In: Neidhardt FC, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press; Washington DC: 1996. pp. 792–821. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu M, Gupte G, Roy S, Bandwar RP, Patel SS, Garges S. Kinetics of transcription initiation at lacP1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39755–39761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dayton CJ, Prosen DE, Parker KL, Cech CL. Kinetic measurement of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase association with bacteriophage T7 early promoters. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1616–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fried MG, Crothers DM. Equilibrium studies of the cyclic-amp receptor protein-DNA interaction. J Mol Biol. 1984;172:241–262. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong P, Gladney S, Keasling JD. Mathematical model of the lac operon: inducer exclusion, catabolite repression, and diauxic growth on glucose and lactose. Biotechnol Prog. 1997;13:132–143. doi: 10.1021/bp970003o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42 ••.Vilar JMG, Saiz L. DNA looping in gene regulation: from the assembly of macromolecular complexes to the control of transcriptional noise. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.02.005. in press. The authors give a physical explanation of the role of DNA looping in transcriptional regulation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seabold RR, Schleif RF. Apo-AraC actively seeks to loop. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:529–538. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aurell E, Brown S, Johanson J, Sneppen K. Stability puzzles in phage λ. Phys Rev. 2002;E65:05194. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.051914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joung JK, Le LU, Hochschild A. Synergistic activation of transcription by Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3083–3087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]