Upper gastrointestinal function and glycemic control in diabetes mellitus (original) (raw)

Abstract

Recent evidence has highlighted the impact of glycemic control on the incidence and progression of diabetic micro- and macrovascular complications, and on cardiovascular risk in the non-diabetic population. Postprandial blood glucose concentrations make a major contribution to overall glycemic control, and are determined in part by upper gastrointestinal function. Conversely, poor glycemic control has an acute, reversible effect on gastrointestinal motility. Insights into the mechanisms by which the gut contributes to glycemia have given rise to a number of novel dietary and pharmacological strategies designed to lower postprandial blood glucose concentrations.

Keywords: Blood glucose, Diabetes mellitus, Gastric Emptying, Gastrointestinal motility, Hyperglycemia

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes and its long-term complications, which include cardiovascular, renal, neurologic, and ophthalmic disease, represent a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world[1]. The prevalence of both type 1 (insulin-dependant) and type 2 (non insulin-dependant) diabetes is increasing, the latter as a consequence of obesity. In the US, 29 million people and 14% of adults have diabetes or impaired fasting glucose, of whom about a third are undiagnosed[2]. Similar figures are evident throughout the developed world[3].

Hyperglycemia is central to the pathogenesis of diabetic micro- and macrovascular complications[4]. There is increasing evidence that postprandial hyperglycemia is the major determinant of “average” glycemic control, and represents an independent risk factor for macrovascular disease, even in people without diabetes[5]. While the relative importance of individual determinants of the blood glucose response to a meal remain to be clarified precisely, it is clear that upper gastrointestinal motility has a major impact that has generally been overlooked. Moreover, postprandial glycemic control in turn has a profound effect on the motor function of the upper gut. Hence, blood glucose concentration is determined by, as well as a determinant of, gastric and small intestinal motility[6].

The aims of this review are to examine (1) evidence relating to the importance of postprandial, as opposed to fasting, glycemia in the development and progression of diabetic complications, (2) the contribution of upper gastrointestinal function to postprandial blood glucose concentrations, (3) the impact of variations in glycemia on gastric and small intestinal motility, and (4) the therapeutic strategies suggested by these insights.

IMPACT OF POSTPRANDIAL GLYCEMIA ON COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES

The DCCT/EDIC and UKPDS trials established that the onset and progression of microvascular, and probably macrovascular complications of diabetes, are related to “average” glycemic control, as assessed by glycated hemoglobin[4,7,8]. This provides a rationale for the widespread use of intensive therapy directed at the normalisation of glycemia. In the recently reported DCCT/EDIC study, a period of intensive, as opposed to conventional, therapy for a period of 6.5 years between 1983 and 1993 was shown to be associated with a reduction in the risk of a subsequent cardiovascular event by 42%[4]. Glycated hemoglobin is potentially influenced by both fasting and postprandial blood glucose concentrations. However, given that the stomach empties ingested nutrients at a closely regulated overall rate of 2-3 kcal per minute[9,10] and humans ingest around 2500 kcal daily, it is clear that most individuals spend the majority of each day in either the postprandial or post-absorptive phase with a limited duration of true “fasting” for perhaps three or four hours before breakfast[11]. Hence, the traditional focus on the control of “fasting” blood glucose in diabetes management appears inappropriate.

It is well established that postprandial hyperglycemia precedes elevation of fasting blood glucose in the evolution of diabetes[12]. Furthermore, it appears to be the better predictor of coronary artery[13] and cerebrovas-cular[14] complications, and predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, even in the general population without known diabetes[15]. Blood glucose values at two hours during an oral glucose tolerance test are a better predictor of mortality than fasting blood glucose[16], and reduction in cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with control of postprandial, as opposed to fasting, glycemia[17]. For example, patients with impaired glucose tolerance who were treated with the α-glucosidase inhibitor acarbose, to reduce postprandial glycemia, experienced a reduction in cardiovascular risk of about a third compared to placebo during a mean of three years follow-up[18]. Postprandial blood glucose concentrations correlate well with glycated hemoglobin in the setting of mild to moderate hyperglycemia[19], with fasting blood glucose only assuming greater importance at higher HbA1c values[20]. There is also evidence that therapy directed towards lowering postprandial blood glucose concentrations may have a greater impact on HbA1c than attention to fasting blood glucose[21].

Hyperglycemia potentially has diverse effects on blood vessels. In the short term, hyperglycemia is associated with activation of protein kinase C, which affects endothelial permeability, cell adhesion, and proliferation in the vessel wall. Over the longer term, non-enzymatic glycosylation of proteins results in atherosclerosis[22]. Elevated postprandial blood glucose concentrations are associated with an increase in plasma biochemical markers of oxidative stress[23,24]. However, to what degree hyperglycemia per se accounts for this effect, as opposed to concurrent elevations of non-esterified fatty acids and triglycerides, remains to be elucidated[25].

CONTRIBUTION OF UPPER GASTROINTE-STINAL FUNCTION TO POSTPRANDIAL GLYCEMIA

Postprandial blood glucose levels are potentially affected by a number of factors, including pre-prandial blood glucose concentration, food properties such as viscosity, fibre content, and quantity and type of carbohydrate, gastric emptying, small intestinal delivery and absorption of nutrients, insulin secretion, hepatic glucose metabolism, and peripheral insulin sensitivity[26]. The relative importance of these factors is likely to vary with time after a meal, and between healthy subjects and patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. While it is logical that the gastrointestinal tract, which controls the rate at which ingested carbohydrate is absorbed and releases peptides that stimulate insulin secretion, should have a major impact on postprandial glycemia, its role has frequently been overlooked and generally underestimated in the past. The rate of gastric emptying is now established as a major contributor to variations in glycemia, while the influence of small intestinal motor function represents a current research focus.

Gastric emptying

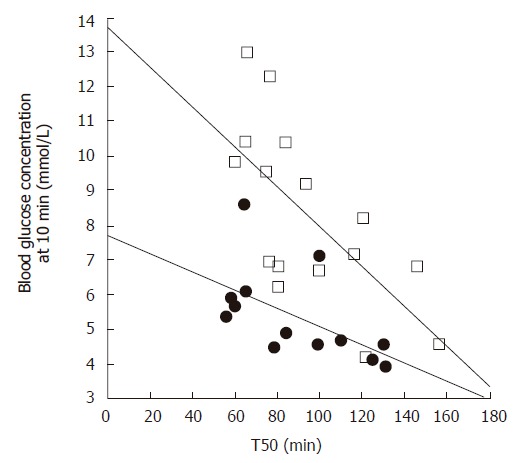

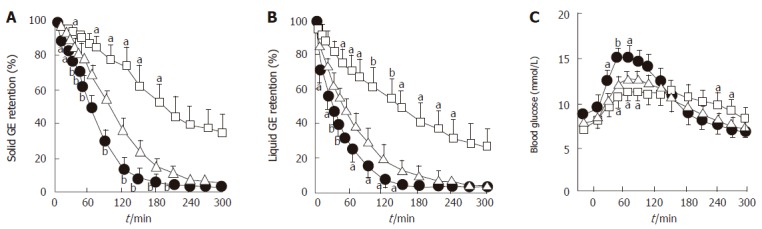

Gastric emptying accounts for at least 35% of the variance in the initial rise as well as the peak blood glucose levels after an oral glucose load in both healthy individuals[27] and patients with type 2 diabetes[28] (Figure 1). Pharmacological slowing of gastric emptying by morphine reduces the postprandial glycemic response to a mixed meal in type 2 patients, whilst acceleration of gastric emptying by erythromycin (a motilin agonist) increases postprandial blood glucose concentrations (Figure 2). Here, differences in peak blood glucose values are more marked than those in the area under the blood glucose curve[29]. In type 1 patients the glycemic response to a meal, and therefore the requirement for exogenous insulin, is also critically dependent on the rate of gastric emptying. Here, when emptying is slower, the insulin requirement to achieve euglycemia is less[30].

Figure 1.

Relationship between the blood glucose concentration 10 min after consuming 75 g glucose in 300 mL water, and the gastric half-emptying time (T50) in patients with type 2 diabetes (open squares, r = -0.67, P < 0.005) and healthy subjects (filled circles, r = -0.56, P < 0.05). Adapted from Jones et al 1996[28].

Figure 2.

Effects of erythromycin (200 mg iv, filled circles) and morphine (8 mg iv, open squares) compared to placebo (open triangles) on (A) solid and (B) liquid gastric emptying and (C) blood glucose concentration in 9 patients with type 2 diabetes. a_P_ < 0.05, b_P_ < 0.01 vs placebo. Adapted from Gonlachanvit et al 2003[29].

In health, gastric emptying is modulated by feedback arising from the interaction of nutrients with the small intestine, so that the overall rate of gastric emptying is closely regulated at about 2-3 kcal per minute[9]. Infusion of a caloric load directly into the small intestine slows gastric emptying by a mechanism that includes relaxation of the gastric fundus, suppression of antral motility, and stimulation of phasic and tonic pressures in the pylorus[31,32]; the latter acts as a brake to gastric outflow. The length of small intestine exposed to nutrient appears to be the primary determinant of the magnitude of the feedback response[33,34]. Both transection of duodenal intramural nerves[35], and suppression of the release of small intestinal peptides by the somatostatin agonist, octreotide[36], accelerate the emptying of nutrient liquids, indicating the involvement of both neural and humoral mechanisms in mediating feedback from the small intestine. Glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which suppresses antral and duodenal motility and stimulates pyloric contractions[37-39], probably represents one such humoral mediator, and the slowing of gastric emptying by this peptide appears likely to be the major mechanism by which its administration improves postprandial glycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes[40]. While the contribution of endogenous GLP-1 in regulating gastric emptying remains to be clarified (i.e. the “physiological” as opposed to “pharmacological” action), a recent study using the GLP-1 antagonist, exendin (9-39) amide, confirmed that endogenous GLP-1 mediates the suppression of antral motility and stimulation of pyloric pressures induced by the presence of glucose in the small intestine[38].

It has long been recognised that oral or enteral administration of glucose results in a much greater insulin response than an equivalent intravenous glucose load[41-44], a phenomenon referred to as the “incretin” effect. The putative incretin peptides, GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), are released from the small intestine in response to nutrients[45], apparently in a load-dependent fashion[46]. Therefore, the rate of delivery of carbohydrate from the stomach into the small intestine is likely to be critical in determining not only the rate of glucose absorption, but also the incretin response. Although GIP is the more potent of the two hormones in healthy individuals[47], the insulinotropic effect of GIP appears to be markedly diminished in patients with type 2 diabetes, while the insulin response to GLP-1 is retained[45]. This forms a rationale for the therapeutic use of GLP-1 and its analogs in the management of type 2 diabetes (to be discussed). There is limited evidence that type 2 diabetes is associated with an impaired GLP-1 response to oral glucose[48], but to what degree delayed gastric emptying, which occurs frequently in type 2 patients[49], accounts for this decrease in GLP-1 has not been evaluated.

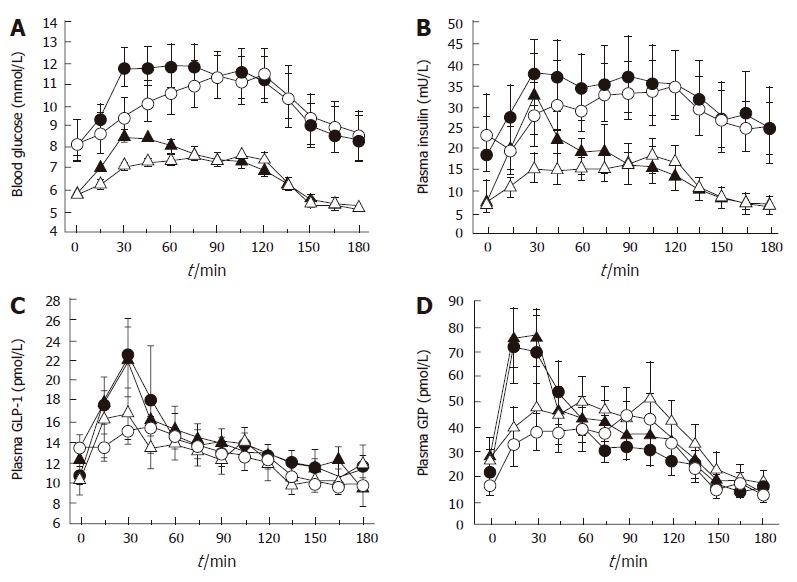

In considering the potential impact of gastric emptying on postprandial glycemia, the initial rate of glucose entry into the small intestine (“early phase” of gastric emptying) may be particularly important[50]. Type 2 diabetes is characterised by a reduced “early”, and frequently increased “late”, postprandial insulin response. Studies in rodents have established the importance of “early” insulin release as a determinant of postprandial glucose excursions, in that a small “early” increase in portal vein/ peripheral blood insulin is more effective than a larger, “later” increase at reducing blood glucose levels[51]. A recent study involving both healthy subjects and type 2 patients, established that modest physiological variations in the initial rate of small intestinal glucose entry have major effects on the subsequent glycemic, insulin and incretin responses (Figure 3)[52]. Nevertheless, while initially rapid, and subsequently slower, duodenal glucose delivery can boost incretin and insulin responses when compared to constant delivery of an identical glucose load, the overall glycemic excursion is, if anything, greater[52], and certainly not improved[53]. This evidence adds to the rationale for the use of dietary and pharmacological strategies designed to reduce postprandial glycemic excursions by slowing gastric emptying, rather than initially accelerating it. However, the “dose-response” relationship between duodenal glucose delivery and glycemia remains to be clearly determined.

Figure 3.

Effect of initially more rapid intraduodenal glucose infusion (3 kcal/min between t = 0 and 15 min and 0.71 kcal/min between t = 15 and 120 min) (closed symbols) compared to constant infusion (1 kcal/min between t = 0 and 120 min) (open symbols) in healthy subjects (triangles) and patients with type 2 diabetes (circles) on (A) blood glucose, (B) plasma insulin, (C) plasma GLP-1, and (D) plasma GIP. Each pair of curves differs between 0 and 30 min for variable vs constant intraduodenal infusion (P < 0.05). Adapted from O’Donovan et al 2004[52].

Small intestinal glucose absorption

The gut lumen is the site of absorption of glucose from the external environment into the body, as well as being the source of the incretin peptides that drive much of the postprandial insulin response. Thus, it is logical that variations in small intestinal function should be a major determinant of postprandial glycemia. Nevertheless, there is little information about the impact of small intestinal motility and absorptive function on glycemia, at least in part because of the technical demands in studying this region of gastrointestinal tract[6,54].

The large surface area of the small intestine is well suited to absorption of water and solutes. Perfusion studies in healthy humans have established that the proximal jejunum has a maximal absorptive capacity for glucose of approximately 0.5 g per minute per 30 cm[55-57]. Small intestinal mucosal hypertrophy occurs in animal models of diabetes, with concomitant increases in glucose absorption, but this is rapidly reversed by insulin treatment[58]. However, acute hyperglycemia does result in transient increases in intestinal glucose absorption in rodents[59-61]. The few studies performed in humans with type 1[62] “insulin-requiring”[63], or type 2[64] diabetes have not demonstrated increased small intestinal glucose absorption, other than one report of increased absorption at high luminal glucose concentrations[65]. Attention was paid to maintaining euglycemia in at least one of these studies[63]. However, there is a recent report of increased expression of monosaccharide transporters in humans with type 2 diabetes[66], the clinical significance of which remains to be clarified. One human study failed to demonstrate an effect of marked hyperglycemia (14 mmol/L) on jejunal glucose absorption in healthy subjects[63], although a relationship has been observed between more physiological postprandial blood glucose concentrations (less than 10 mmol/L) and the absorption of the glucose analog, 3-O-methylglucose, in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes[67]. Hence, the effect of transient hyperglycemia on small intestinal glucose absorption remains uncertain.

Given that an upper limit exists for absorption of glucose across the small intestinal mucosa, it is logical that patterns of intestinal motility which serve to spread luminal glucose over a large surface area could promote glucose absorption. Furthermore, certain motor patterns could facilitate mixing of complex carbohydrates with digestive enzymes, and their exposure to brush border disaccharidases. Thus, when glucose is infused directly into the duodenum, its rate of absorption increases with the number of duodenal pressure waves and propagated pressure wave sequences[54,67]. Further insights into the effects of luminal flow on glucose absorption are likely to require additional techniques, such as intraluminal impedance measurement, in which inferences can be made regarding movement of fluid boluses by measuring changes in electrical impedance between sequential pairs of intraluminal electrodes. A preliminary study in healthy humans using this technique indicates that pharmacological suppression of intraduodenal flow with an anticholinergic agent is associated with delayed absorption of luminal glucose[68]. These observations are likely to be of relevance to patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, who demonstrate an increased frequency of small intestinal pressure waves in the postprandial state[67].

The region of small intestine that is exposed to carbohydrate is also likely to be a determinant of the glycemic response. GLP-1 is released from intestinal L cells, whose concentration is greatest is the distal jejunum, with fewer L cells located in the proximal jejunum, ileum, and colon[69]. In humans, it is unclear whether nutrients must interact directly with L cells to stimulate GLP-1 release. A neural or endocrine loop between the duodenum and the more distal small bowel has been postulated[70], but remains unproven. The lack of a GLP-1 response when glucose is infused into the duodenum below a certain dose (1.4 kcal/min)[71] would be consistent with the concept of complete absorption of the glucose load high in the small intestine, precluding significant interaction with L cells, although other investigators have reported a GLP-1 response even with 1 kcal/min intraduodenal glucose infusion[52]. Nevertheless, GLP-1 responses to meals are enhanced following intestinal bypass procedures that promote access of nutrients to more distal small intestine[72-75], while inhibition of sucrose digestion in the proximal small intestine with acarbose increases the GLP-1 response[76], presumably by facilitating more distal interaction of the intestine with glucose. It follows that dietary modifications that favor exposure of more distal small intestinal segments to glucose could reduce glycemic excursions by stimulating GLP-1 release. Furthermore, a major action of both GLP-1 and peptide YY, which is also released from L cells, is to retard gastric emptying, thus slowing any further entry of carbohydrate to the small intestine[77].

IMPACT OF VARIATIONS IN GLYCEMIA ON UPPER GUT MOTILITY

Acute changes in the blood glucose concentration are now recognised to have a major, reversible impact on the motor function of every region of the gastrointestinal tract. This may in part account for the poor correlation of upper gastrointestinal dysfunction in diabetes with evidence of irreversible autonomic neuropathy, to which it has traditionally been attributed[78]. When compared to euglycemia (4-6 mmol/L), gut motility is modulated through the range of blood glucose concentrations from marked hyperglycemia (greater than 12 mmol/L), through “physiological” blood glucose elevation (8-10 mmol/L), to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (less than 2.5 mmol/L), and effects are observed rapidly (within minutes), although the thresholds of response may differ between gut regions[6]. The mechanisms mediating the effects of acute changes in the blood glucose concentration are poorly defined, and the potential impact of chronic, as opposed to acute, variations in glycemia on gastrointestinal motility has hitherto received little attention. Nevertheless, it is clear that gut motor function and postprandial glycemia are highly interdependent variables.

Gastric motility

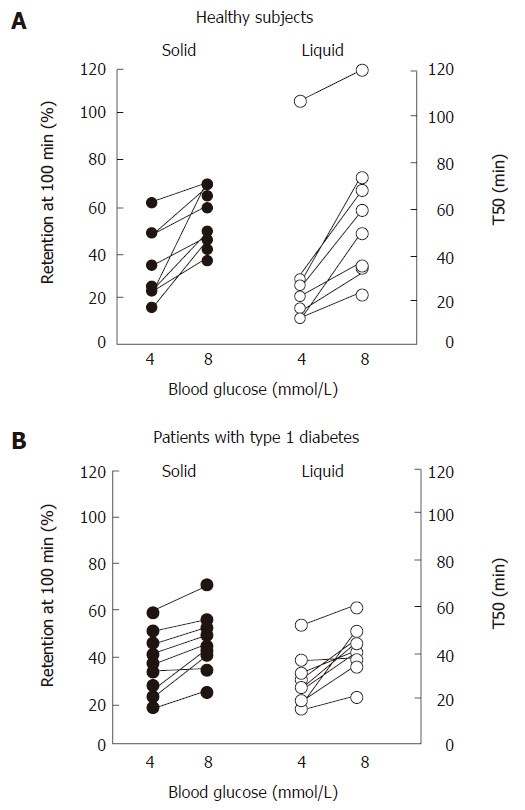

Marked hyperglycemia (16-20 mmol/L) slows both solid and nutrient liquid emptying in patients with type 1 diabetes when compared to euglycemia (5-8 mmol/L)[79]; in type 2 patients, cross-sectional data also indicate an inverse relationship between the blood glucose concentration and the rate of gastric emptying[49]. Conversely, gastric emptying is accelerated by acute hypoglycemia induced by insulin (2.6 mmol/L) in healthy subjects[80] and type 1 patients, even when emptying is slower than normal during euglycemia[81]. In type 1 diabetes, as well as healthy volunteers, elevation of blood glucose to “physiological” postprandial levels (8 mmol/L) also slows gastric emptying when compared to euglycemia (4 mmol/L)[82] (Figure 4). The magnitude of the effects of glycemia on the rate of gastric emptying is substantial, and has implications for absorption of orally administered medications, including oral hypoglycemic agents[83], as well as impacting on carbohydrate absorption.

Figure 4.

Solid and liquid gastric emptying in (A) healthy subjects and (B) patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus during euglycemia (blood glucose 4 mmol/L) and “physiological” hyperglycemia (blood glucose 8 mmol/L). Adapted from Schvarcz et al 1997[82].

The rate of gastric emptying is determined by the coordinated activity of various regions of the stomach and proximal small intestine[84]. The proximal stomach acts as a reservoir for solids and generates tonic pressure to facilitate liquid emptying. The distal stomach grinds and sieves solids and pumps chyme across the pylorus, predominantly in a pulsatile manner, while phasic and tonic pyloric pressures, and duodenal contractile activity act as a break to gastric outflow. The timing of antral contractions is controlled by an electrical slow wave, with a frequency of about 3 per minute, generated by the interstitial cells of Cajal[85]. During fasting, cyclical activity of gastric motility is observed, with a periodicity of about 90 min, characterised by irregular contractions of increasing frequency (phase II), and a brief (5-10 min) period of regular contractions at the rate of 3 per minute (phase III) during which indigestible solids empty from the stomach, followed by motor quiescence (phaseI). Acute hyperglycemia is associated with diminished proximal gastric tone[86-88], suppression of both the frequency and propagation of antral pressure waves[89-92], and stimulation of pyloric contractions[93] -a motor pattern associated with slowing of gastric emptying. The frequency of the gastric slow wave is also disturbed[94]. The suppression of antral motility is observed at blood glucose concentrations as low as 8 mmol/L[89,91]; the threshold appears higher in the proximal stomach[95]. Hyperglycemia also attenuates the prokinetic effects of erythromycin in both healthy subjects and type 1 patients[96,97], at least in part by inhibiting the stimulation of antral waves and coordinated antroduodenal pressure sequences[98]. This effect is of considerable importance, since the action of other prokinetic drugs is also likely to be impaired during hyperglycemia, although this issue has not been specifically examined.

Small intestinal motility

As in the stomach, fasting small intestinal motility is cyclical, and characterised by phasesIto III, the latter with a frequency of 9 to 12 per minute. This “migrating motor complex” (MMC) propagates aborally along the small intestine, and serves to “sweep” the lumen of indigestible debris. After a meal, the MMC is interrupted by irregular contractions propagated over short distances, which facilitate digestion and absorption of nutrients.

In healthy subjects during hyperglycemia (10 mmol/L), the duodenum becomes less compliant (more “stiff”) to balloon distension, while distension stimulates a greater number of phasic pressure waves, when compared to euglycemia[99]. Both phenomena could contribute to a duodenal “brake” to gastric emptying. More marked hyperglycemia (12-15 mmol/L) reduces the cycle length of the MMC[100], the frequency of duodenal and jejunal pressure waves, and the duration of the postprandial period (early return of phase III activity), and slows small intestinal transit[101]. These alterations in function could have implications for absorption of nutrients and medications, alteration in bowel habit, and the occurrence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in diabetes[102]. However, other than suppression of proximal duodenal wave frequency[103], there is limited information about the effects of hyperglycemia on small intestinal motor function in patients, as opposed to healthy volunteers.

Mechanisms mediating the effects of hyperglycemia on gastric and small intestinal motility

Most information about the etiology of gastrointestinal dysfunction in diabetes relates to the effects of longstanding diabetes rather than acute, reversible changes that could relate to transient hyperglycemia[104]. Rodent models of diabetes have demonstrated marked apoptosis of enteric neurons[105], affecting nitrergic (inhibitory) neurons in particular[106], and loss of interstitial cells of Cajal[107]. The latter are also deficient in humans with diabetes and severe gut symptoms[108]. Hyperglycemia appears to be responsible for apoptosis of enteric neurons[109], but the latter would seem unlikely to mediate changes that are evident within minutes, rather than days or weeks. Enteric neurons sensitive to changes in glucose have been identified[110], although their responsiveness to systemic, as opposed to luminal glucose remains unclear. Vagal nerve function is reversibly inhibited by acute hyperglycemia[111,112], and this may account for some of the observed phenomena. Hyperinsulinemia is unlikely to explain the observed effects, particularly as they are seen in type 1 (insulin deficient) as well as type 2 and healthy subjects. Studies are indicated to determine whether reversible changes in nitrergic or serotonergic neurotransmission occur with variations in glycemia.

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES DIRECTED AT MINIMISING POSTPRANDIAL GLYCEMIA

The major impact of gastrointestinal function on the glycemic response to meals, as outlined above, suggests a number of logical, and in many cases complimentary, strategies to lower postprandial blood glucose concentrations (Table 1). These include (1) minimising the carbohydrate content, or substituting low- for high-glycemic index foods in meals, (2) slowing gastric emptying, even in individuals with modest delays in emptying provided they remain free of symptoms, (3) inhibiting the absorption of carbohydrate from the small intestine, or delaying its absorption to more distal small intestinal segments, and (4) augmenting the incretin response. Many approaches fulfill a number of these aims concurrently. Most studies relating elevated postprandial glycemia with cardiovascular risk have evaluated blood glucose 2 h after a meal[113], suggesting that lowering peak blood glucose may be an appropriate target. Nevertheless, the glycated hemoglobin relates closely to the integrated mean blood glucose (i.e. area under the curve) over 24 h, albeit with a curvilinear rather then linear relationship[114], so reducing the total area under the blood glucose excursion over several hours after a meal may also be an important goal. It should be noted that strategies for individuals with impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes managed without exogenous insulin, particularly those involving slowing of gastric emptying, may not be applicable to type 1 and insulin-requiring type 2 patients, in whom the goal should be to coordinate the absorption of carbohydrate with the action of exogenous insulin, which in some cases may involve accelerating gastric emptying, if it is already delayed[115].

Table 1.

Therapeutic strategies directed at minimizing postprandial glycemia

| Strategy | Examples |

|---|---|

| Alter carbohydrate in diet | Low-carbohydrate diets |

| Low glycemic index carbohydrates | |

| Slow gastric emptying | High fiber diets |

| Fat “preloads” | |

| Low glycemic index carbohydrates | |

| Acarbose | |

| GLP-1 analogs and DPP-IV inhibitors | |

| Pramlintide | |

| Inhibit small intestinal carbohydrate absorption | Acarbose |

| High fiber diets | |

| Low glycemic index carbohydrates | |

| Augment the incretin response | GLP-1 analogs and DPP-IV inhibitors |

| Acarbose | |

| Fat “preloads” | |

| ? Low glycemic index carbohydrates |

Carbohydrate content and glycemic index

Low-carbohydrate diets were the mainstay of treatment for diabetes in the pre-insulin era[116]. The outcome of the Nurses’ Health Study is indicative of a relationship between both cardiovascular risk and the incidence of diabetes with dietary glycemic load[117]. Short-term studies indicate the potential for low-carbohydrate diets to improve 24 h glycemia and glycated hemoglobin in patients with type 2 diabetes[118], including those failing conventional treatment with diet and a sulfonylurea[119]. In medium- to long-term studies, substituting protein for carbohydrate improved glycemia in overweight hyperinsulinemic subjects[120], while a low-carbohydrate diet improved fasting glucose over 6 mo in type 2 patients, with glycemic benefits maintained at 1 year, when compared to a low-fat diet[121,122]. The magnitude of the decrease in glycated hemoglobin was small (mean 0.6% in the latter study), but likely to be clinically significant. In addition to the reduction in carbohydrate load, protein itself might improve glycemia by stimulating insulin release[123], although this phenomenon is less apparent in medium- versus short-term studies[124].

Rather than trading carbohydrates for alternative macronutrients, another approach is to substitute low- for high-glycemic index carbohydrates. The glycemic index (GI) compares the blood glucose response of a test food with that of a standard carbohydrate, either glucose or white bread[125]. Foods may be low GI by virtue of a relative delay in gastric emptying and/or small intestinal glucose absorption[126,127]. For example, spaghetti (low GI) empties from the stomach much slower than potato (high GI) from about 60 min after the meal, although their glycemic profiles diverge earlier[128], indicating that slowing of small intestinal glucose absorption is important. Both the physical properties of the carbohydrate (such as enclosed kernels) and its chemical composition (such as a high amylose:amylopectin ratio) influence small intestinal carbohydrate digestion and absorption[127,129]. Glycemic index tends to vary inversely with the content of dietary fiber in meals[130]; dietary fiber per se potentially slows gastric emptying[131] and small intestinal carbohydrate absorption[132], the latter by a mechanism that includes modification of small intestinal motility from a stationary (favoring mixing), to a propulsive pattern. The beneficial effect on the glycemic response of adding guar gum to an oral glucose load appears to be achieved mainly by slowing gastric emptying[133,134]. Nevertheless, guar also slows small intestinal glucose absorption, probably by inhibiting diffusion of glucose out of the luminal contents[135]; this is reflected in the observation that both GLP-1 and insulin responses are less than with guar-free glucose[136].

Low GI foods may also stimulate insulin release through the incretin effect, or other mechanisms[137]. Furthermore, they may enhance satiety and reduce energy intake at a subsequent meal[138,139]. Additional information about the potential for these beneficial effects from different classes of low GI foods is needed. Fructose has been advocated as a low GI substitute for glucose in the diabetic diet, since it results in a much lower glycemic excursion than an equivalent glucose load[140], while retaining the capacity to stimulate insulin secretion[141]. In addition, some investigators have found that fructose ingestion suppresses food intake more than glucose[140,142], although this issue is controversial[141], and probably depends on the load and timing of fructose ingestion in relation to the subsequent meal.

Most medium- to long-term studies of low GI diets indicate a benefit for glycemic control[143]; typically the effect is modest[144], but is still likely to be clinically meaningful, and in many cases is of similar magnitude to the improvement in glycemic control achieved by pharmacological agents[145].

Slowing gastric emptying

Given the relationship between the degree of postprandial glycemia and the rate of gastric emptying in both healthy subjects[27] and type 2 patients[28], it is logical that dietary and/or pharmacological interventions which slow gastric emptying should be effective in lowering postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes. In addition to the effects of dietary fiber in retarding gastric emptying, slowing of emptying by either an oral proteinase inhibitor[146], adding a solid non-carbohydrate meal to an oral glucose load[147], or combining fat (the most potent macronutrient for slowing gastric emptying[148]) with carbohydrate[149], all reduce postprandial blood glucose and insulin responses. The underlying concept is that the presence of nutrients in the small intestine both delays gastric emptying and stimulates GLP-1 and GIP. Hence, consumption of oil as a “preload” before a mashed potato meal markedly delays the subsequent rise in blood glucose, and stimulates GLP-1 release in patients with type 2 diabetes[150]. This approach requires further refinement to determine the optimum load, timing, and macronutrient content of the “preload”, but has the potential advantage of simplicity when compared to pharmacological strategies, which also appear to act predominantly by slowing gastric emptying. For example, the improvement in postprandial glycemia associated with GLP-1 and its analogs is related to slowing of gastric emptying rather than enhancement of insulin secretion[40]; the latter is in fact reduced due to a decrease in the rate of entry of carbohydrate into the small intestine. The amylin analog, pramlintide, also slows gastric emptying[151], and its use is associated with an improvement in overall glycemic control, as assessed by glycated hemoglobin, with medium-term use in type 1 and type 2 patients[152-155]. Pramlintide has the additional advantage of promoting weight loss, probably by suppressing appetite[156].

Inhibiting absorption of glucose

The α-glucosidase inhibitors, including acarbose, delay absorption of carbohydrates in the proximal small intestine[157]. The resultant exposure of more distal intestinal segments to glucose results in enhanced and prolonged GLP-1 secretion in healthy subjects[76,158], with subsequent slowing of gastric emptying[159]. The magnitude of these affects is likely to depend on meal content (ie. disaccharide load). Moreover, acarbose fails to stimulate GLP-1 release or delay gastric emptying in patients with type 2 diabetes, although it is still beneficial for reducing postprandial glycemia in this group[160], presumably by impairing carbohydrate absorption. Inhibition of glucose entry into enterocytes might represent an additional mode of action of acarbose[161]. Again, it is clear that the mechanisms by which postprandial glycemia is improved frequently overlap. For example, slowed absorption of glucose, as discussed, is also a feature of low GI and high fiber diets.

Augmenting the incretin response

The effect on GLP-1 concentrations of the dietary strategies already discussed, and the observed potentiation of GLP-1 secretion and associated improvement in glycemic control after bariatric surgery[162], point to the value of augmenting the incretin response in optimising postprandial glycemia. GLP-1 is metabolised rapidly by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV), and therefore is not a suitable agent for therapeutic administration. Instead, longer lasting agonists have been developed, including both albumin-bound analogs of GLP-1, and exendin-4, a peptide derived from the saliva of the Gila monster lizard, which is structurally similar to GLP-1 and shares several biological properties, but may be a more potent insulinotropic agent than GLP-1[26]. Subcutaneous administration has been shown to reduce postprandial glycemia in type 2 patients[163]. Resistant analogs of GLP-1, along with DPP-IV inhibitors, appear to have a promising role in the therapy of diabetes[164].

CONCLUSION

Upper gastrointestinal function plays a major, though often overlooked, role in determining postprandial glycemia. Recent insights into the mechanisms by which variations in gut function alter the blood glucose concentration have suggested a number of potential therapeutic strategies that require further evaluation for their utility in achieving good glycemic control.

Footnotes

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Lalor PF E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Nelson DE, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F, Marks JS. Diabetes trends in the U.S.: 1990-1998. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1278–1283. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults--United States, 1999-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunstan DW, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, De Courten MP, Cameron AJ, Sicree RA, Dwyer T, Colagiuri S, Jolley D, Knuiman M, et al. The rising prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:829–834. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, Raskin P, Zinman B. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Prato S. In search of normoglycaemia in diabetes: controlling postprandial glucose. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26 Suppl 3:S9–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rayner CK, Samsom M, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Relationships of upper gastrointestinal motor and sensory function with glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:371–381. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brener W, Hendrix TR, McHugh PR. Regulation of the gastric emptying of glucose. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt JN, Smith JL, Jiang CL. Effect of meal volume and energy density on the gastric emptying of carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1326–1330. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monnier L. Is postprandial glucose a neglected cardiovascular risk factor in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30 Suppl 2:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebovitz HE. Postprandial hyperglycaemic state: importance and consequences. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;40 Suppl:S27–S28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkau B, Shipley M, Jarrett RJ, Pyörälä K, Pyörälä M, Forhan A, Eschwège E. High blood glucose concentration is a risk factor for mortality in middle-aged nondiabetic men. 20-year follow-up in the Whitehall Study, the Paris Prospective Study, and the Helsinki Policemen Study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:360–367. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki Y, Kawamori R, Matsushima H, Nishizawa H, Kodama M, Kubota M, Kajimoto Y, Kamada T. Asymptomatic hyperglycaemia is associated with increased intimal plus medial thickness of the carotid artery. Diabetologia. 1995;38:585–591. doi: 10.1007/BF00400728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Ruhé HG, Stehouwer CD, Nijpels G, Bouter LM, Heine RJ. Hyperglycaemia is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the Hoorn population: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 1999;42:926–931. doi: 10.1007/s001250051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria. The DECODE study group. European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative analysis Of Diagnostic criteria in Europe. Lancet. 1999;354:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanefeld M, Fischer S, Julius U, Schulze J, Schwanebeck U, Schmechel H, Ziegelasch HJ, Lindner J. Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly detected NIDDM: the Diabetes Intervention Study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1577–1583. doi: 10.1007/s001250050617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M. Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP-NIDDM trial. JAMA. 2003;290:486–494. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Kebbi IM, Ziemer DC, Cook CB, Gallina DL, Barnes CS, Phillips LS. Utility of casual postprandial glucose levels in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:335–339. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c) Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–885. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastyr EJ 3rd, Stuart CA, Brodows RG, Schwartz S, Graf CJ, Zagar A, Robertson KE. Therapy focused on lowering postprandial glucose, not fasting glucose, may be superior for lowering HbA1c. IOEZ Study Group. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1236–1241. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haller H. The clinical importance of postprandial glucose. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;40 Suppl:S43–S49. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(98)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceriello A. Acute hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress generation. Diabet Med. 1997;14 Suppl 3:S45–S49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9136(199708)14:3+s45::aid-dia4443.3.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceriello A. The emerging role of post-prandial hyperglycaemic spikes in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabet Med. 1998;15:188–193. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199803)15:3<188::AID-DIA545>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heine RJ, Dekker JM. Beyond postprandial hyperglycaemia: metabolic factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia. 2002;45:461–475. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz M, O'Donovan D, Jones KL, Feinle C, Rayner CK, Samsom M. Gastric emptying in diabetes: clinical significance and treatment. Diabet Med. 2002;19:177–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horowitz M, Edelbroek MA, Wishart JM, Straathof JW. Relationship between oral glucose tolerance and gastric emptying in normal healthy subjects. Diabetologia. 1993;36:857–862. doi: 10.1007/BF00400362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones KL, Horowitz M, Carney BI, Wishart JM, Guha S, Green L. Gastric emptying in early noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1643–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonlachanvit S, Hsu CW, Boden GH, Knight LC, Maurer AH, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Effect of altering gastric emptying on postprandial plasma glucose concentrations following a physiologic meal in type-II diabetic patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:488–497. doi: 10.1023/a:1022528414264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishii M, Nakamura T, Kasai F, Onuma T, Baba T, Takebe K. Altered postprandial insulin requirement in IDDM patients with gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:901–903. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.8.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heddle R, Collins PJ, Dent J, Horowitz M, Read NW, Chatterton B, Houghton LA. Motor mechanisms associated with slowing of the gastric emptying of a solid meal by an intraduodenal lipid infusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:437–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1989.tb01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heddle R, Miedema BW, Kelly KA. Integration of canine proximal gastric, antral, pyloric, and proximal duodenal motility during fasting and after a liquid meal. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:856–869. doi: 10.1007/BF01295912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin HC, Doty JE, Reedy TJ, Meyer JH. Inhibition of gastric emptying by glucose depends on length of intestine exposed to nutrient. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:G404–G411. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.256.2.G404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin HC, Doty JE, Reedy TJ, Meyer JH. Inhibition of gastric emptying by sodium oleate depends on length of intestine exposed to nutrient. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G1031–G1036. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.6.G1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treacy PJ, Jamieson GG, Dent J, Devitt PG, Heddle R. Duodenal intramural nerves in control of pyloric motility and gastric emptying. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:G1–G5. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM, Akkermans LM, Jansen JB, Gouma DJ. The effect of octreotide on gastric emptying at a dosage used to prevent complications after pancreatic surgery: a randomised, placebo controlled study in volunteers. Gut. 1997;41:758–762. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schirra J, Houck P, Wank U, Arnold R, Göke B, Katschinski M. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide on antro-pyloro-duodenal motility in the interdigestive state and with duodenal lipid perfusion in humans. Gut. 2000;46:622–631. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.5.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schirra J, Nicolaus M, Roggel R, Katschinski M, Storr M, Woerle HJ, Göke B. Endogenous glucagon-like peptide 1 controls endocrine pancreatic secretion and antro-pyloro-duodenal motility in humans. Gut. 2006;55:243–251. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.059741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horowitz M, Nauck MA. To be or not to be--an incretin or enterogastrone. Gut. 2006;55:148–150. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.071787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nauck MA, Niedereichholz U, Ettler R, Holst JJ, Orskov C, Ritzel R, Schmiegel WH. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibition of gastric emptying outweighs its insulinotropic effects in healthy humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E981–E988. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.5.E981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ELRICK H, STIMMLER L, HLAD CJ, ARAI Y. PLASMA INSULIN RESPONSE TO ORAL AND INTRAVENOUS GLUCOSE ADMINISTRATION. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1964;24:1076–1082. doi: 10.1210/jcem-24-10-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIntyre N, Holdsworth CD, Turner DS. Intestinal factors in the control of insulin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1965;25:1317–1324. doi: 10.1210/jcem-25-10-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perley MJ, Kipnis DM. Plasma insulin responses to oral and intravenous glucose: studies in normal and diabetic sujbjects. J Clin Invest. 1967;46:1954–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI105685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Creutzfeldt W. The incretin concept today. Diabetologia. 1979;16:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01225454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holst JJ, Gromada J. Role of incretin hormones in the regulation of insulin secretion in diabetic and nondiabetic humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E199–E206. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00545.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schirra J, Katschinski M, Weidmann C, Schäfer T, Wank U, Arnold R, Göke B. Gastric emptying and release of incretin hormones after glucose ingestion in humans. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:92–103. doi: 10.1172/JCI118411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meier JJ, Nauck MA, Schmidt WE, Gallwitz B. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide: the neglected incretin revisited. Regul Pept. 2002;107:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toft-Nielsen MB, Damholt MB, Madsbad S, Hilsted LM, Hughes TE, Michelsen BK, Holst JJ. Determinants of the impaired secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3717–3723. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horowitz M, Harding PE, Maddox AF, Wishart JM, Akkermans LM, Chatterton BE, Shearman DJ. Gastric and oesophageal emptying in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1989;32:151–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00265086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Donovan D, Hausken T, Lei Y, Russo A, Keogh J, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Effect of aging on transpyloric flow, gastric emptying, and intragastric distribution in healthy humans--impact on glycemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Souza CJ, Gagen K, Chen W, Dragonas N. Early insulin release effectively improves glucose tolerance: studies in two rodent models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2001;3:85–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Donovan DG, Doran S, Feinle-Bisset C, Jones KL, Meyer JH, Wishart JM, Morris HA, Horowitz M. Effect of variations in small intestinal glucose delivery on plasma glucose, insulin, and incretin hormones in healthy subjects and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3431–3435. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaikomin R, Doran S, Jones KL, Feinle-Bisset C, O'Donovan D, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Initially more rapid small intestinal glucose delivery increases plasma insulin, GIP, and GLP-1 but does not improve overall glycemia in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E504–E507. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00099.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz MP, Samsom M, Renooij W, van Steenderen LW, Benninga MA, van Geenen EJ, van Herwaarden MA, de Smet MB, Smout AJ. Small bowel motility affects glucose absorption in a healthy man. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1857–1861. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.HOLDSWORTH CD, DAWSON AM. THE ABSORPTION OF MONOSACCHARIDES IN MAN. Clin Sci. 1964;27:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Modigliani R, Bernier JJ. Absorption of glucose, sodium, and water by the human jejunum studied by intestinal perfusion with a proximal occluding balloon and at variable flow rates. Gut. 1971;12:184–193. doi: 10.1136/gut.12.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duchman SM, Ryan AJ, Schedl HP, Summers RW, Bleiler TL, Gisolfi CV. Upper limit for intestinal absorption of a dilute glucose solution in men at rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:482–488. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomson AB, Wild G. Adaptation of intestinal nutrient transport in health and disease. Part II. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:470–488. doi: 10.1023/a:1018874404762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Csáky TZ, Fischer E. Induction of an intestinal epithelial sugar transport system by high blood sugar. Experientia. 1977;33:223–224. doi: 10.1007/BF02124079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Csáky TZ, Fischer E. Intestinal sugar transport in experimental diabetes. Diabetes. 1981;30:568–574. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.7.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer E, Lauterbach F. Effect of hyperglycaemia on sugar transport in the isolated mucosa of guinea-pig small intestine. J Physiol. 1984;355:567–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gottesbüren H, Schmidt E, Menge H, Bloch R, Lorenz-Meyer H, Riecken EO. The effect of diabetes mellitus and insulin on the absorption of glucose, water and electrolytes by the small intestine in man. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh) 1973;173:130. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.072s130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costrini NV, Ganeshappa KP, Wu W, Whalen GE, Soergel KH. Effect of insulin, glucose, and controlled diabetes mellitus on human jejunal function. Am J Physiol. 1977;233:E181–E187. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1977.233.3.E181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gulliford MC, Bicknell EJ, Pover GG, Scarpello JH. Intestinal glucose and amino acid absorption in healthy volunteers and noninsulin-dependent diabetic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1247–1251. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vinnik IE, Kern F, Sussman KE. The effect of diabetes and insulin on glucose absorption by the small intestine. J Lab Clin Med. 1967;66:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dyer J, Wood IS, Palejwala A, Ellis A, Shirazi-Beechey SP. Expression of monosaccharide transporters in intestine of diabetic humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G241–G248. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00310.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rayner CK, Schwartz MP, van Dam PS, Renooij W, de Smet M, Horowitz M, Smout AJ, Samsom M. Small intestinal glucose absorption and duodenal motility in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3123–3130. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaikomin R, Wu K-L, Doran S, Smout A, Horowitz M, Rayner C. Evaluation of the effects of hyoscine on duodenal motor function using concurrent multiple intraluminal impedance and manometry (Abstract) Gastroenterology. 2005;128:A672–A673. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eissele R, Göke R, Willemer S, Harthus HP, Vermeer H, Arnold R, Göke B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 cells in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas of rat, pig and man. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holst JJ. Glucagonlike peptide 1: a newly discovered gastrointestinal hormone. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1848–1855. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schirra J, Kuwert P, Wank U, Leicht P, Arnold R, Göke B, Katschinski M. Differential effects of subcutaneous GLP-1 on gastric emptying, antroduodenal motility, and pancreatic function in men. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1997;109:84–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lauritsen KB, Christensen KC, Stokholm KH. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) release and incretin effect after oral glucose in obesity and after jejunoileal bypass. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1980;15:489–495. doi: 10.3109/00365528009181506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andrews NJ, Irving MH. Human gut hormone profiles in patients with short bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:729–732. doi: 10.1007/BF01296430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mason EE. Ileal [correction of ilial] transposition and enteroglucagon/GLP-1 in obesity (and diabetic) surgery. Obes Surg. 1999;9:223–228. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jeppesen PB, Hartmann B, Thulesen J, Hansen BS, Holst JJ, Poulsen SS, Mortensen PB. Elevated plasma glucagon-like peptide 1 and 2 concentrations in ileum resected short bowel patients with a preserved colon. Gut. 2000;47:370–376. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gentilcore D, Bryant B, Wishart JM, Morris HA, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Acarbose attenuates the hypotensive response to sucrose and slows gastric emptying in the elderly. Am J Med. 2005;118:1289. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wen J, Phillips SF, Sarr MG, Kost LJ, Holst JJ. PYY and GLP-1 contribute to feedback inhibition from the canine ileum and colon. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G945–G952. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.6.G945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Wishart JM, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Shearman DJ. Relationships between oesophageal transit and solid and liquid gastric emptying in diabetes mellitus. Eur J Nucl Med. 1991;18:229–234. doi: 10.1007/BF00186645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33:675–680. doi: 10.1007/BF00400569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schvarcz E, Palmér M, Aman J, Berne C. Hypoglycemia increases the gastric emptying rate in healthy subjects. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:674–676. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Russo A, Stevens JE, Chen R, Gentilcore D, Burnet R, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia accelerates gastric emptying of solids and liquids in long-standing type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4489–4495. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schvarcz E, Palmér M, Aman J, Horowitz M, Stridsberg M, Berne C. Physiological hyperglycemia slows gastric emptying in normal subjects and patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:60–66. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Groop LC, Luzi L, DeFronzo RA, Melander A. Hyperglycaemia and absorption of sulphonylurea drugs. Lancet. 1989;2:129–130. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horowitz M, Dent J. Disordered gastric emptying: mechanical basis, assessment and treatment. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;5:371–407. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(91)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanders KM. A case for interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:492–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hebbard GS, Samsom M, Sun WM, Dent J, Horowitz M. Hyperglycemia affects proximal gastric motor and sensory function during small intestinal triglyceride infusion. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G814–G819. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.5.G814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hebbard GS, Sun WM, Dent J, Horowitz M. Hyperglycaemia affects proximal gastric motor and sensory function in normal subjects. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:211–217. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rayner CK, Verhagen MA, Hebbard GS, DiMatteo AC, Doran SM, Horowitz M. Proximal gastric compliance and perception of distension in type 1 diabetes mellitus: effects of hyperglycemia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barnett JL, Owyang C. Serum glucose concentration as a modulator of interdigestive gastric motility. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:739–744. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Björnsson ES, Urbanavicius V, Eliasson B, Attvall S, Smith U, Abrahamsson H. Effects of hyperglycemia on interdigestive gastrointestinal motility in humans. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:1096–1104. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hasler WL, Soudah HC, Dulai G, Owyang C. Mediation of hyperglycemia-evoked gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias by endogenous prostaglandins. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:727–736. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90445-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Samsom M, Smout AJ. Abnormal gastric and small intestinal motor function in diabetes mellitus. Dig Dis. 1997;15:263–274. doi: 10.1159/000171603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fraser R, Horowitz M, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia stimulates pyloric motility in normal subjects. Gut. 1991;32:475–478. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.5.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hebbard GS, Samson M, Andrews JM, Carman D, Tansell B, Sun WM, Dent J, Horowitz M. Hyperglycemia affects gastric electrical rhythm and nausea during intraduodenal triglyceride infusion. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:568–575. doi: 10.1023/a:1018851227051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Verhagen MA, Rayner CK, Andrews JM, Hebbard GS, Doran SM, Samsom M, Horowitz M. Physiological changes in blood glucose do not affect gastric compliance and perception in normal subjects. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G761–G766. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jones KL, Berry M, Kong MF, Kwiatek MA, Samsom M, Horowitz M. Hyperglycemia attenuates the gastrokinetic effect of erythromycin and affects the perception of postprandial hunger in normal subjects. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:339–344. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Petrakis IE, Vrachassotakis N, Sciacca V, Vassilakis SI, Chalkiadakis G. Hyperglycaemia attenuates erythromycin-induced acceleration of solid-phase gastric emptying in idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:396–403. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rayner CK, Su YC, Doran SM, Jones KL, Malbert CH, Horowitz M. The stimulation of antral motility by erythromycin is attenuated by hyperglycemia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2233–2241. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lingenfelser T, Sun W, Hebbard GS, Dent J, Horowitz M. Effects of duodenal distension on antropyloroduodenal pressures and perception are modified by hyperglycemia. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G711–G718. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oster-Jørgensen E, Qvist N, Pedersen SA, Rasmussen L, Hovendal CP. The influence of induced hyperglycaemia on the characteristics of intestinal motility and bile kinetics in healthy men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:285–288. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Russo A, Fraser R, Horowitz M. The effect of acute hyperglycaemia on small intestinal motility in normal subjects. Diabetologia. 1996;39:984–989. doi: 10.1007/BF00403919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Virally-Monod M, Tielmans D, Kevorkian JP, Bouhnik Y, Flourie B, Porokhov B, Ajzenberg C, Warnet A, Guillausseau PJ. Chronic diarrhoea and diabetes mellitus: prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Diabetes Metab. 1998;24:530–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Samsom M, Akkermans LM, Jebbink RJ, van Isselt H, vanBerge-Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Gastrointestinal motor mechanisms in hyperglycaemia induced delayed gastric emptying in type I diabetes mellitus. Gut. 1997;40:641–646. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.5.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Gastrointestinal motility and glycemic control in diabetes: the chicken and the egg revisited. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:299–302. doi: 10.1172/JCI27758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fregonesi CE, Miranda-Neto MH, Molinari SL, Zanoni JN. Quantitative study of the myenteric plexus of the stomach of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59:50–53. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2001000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Watkins CC, Sawa A, Jaffrey S, Blackshaw S, Barrow RK, Snyder SH, Ferris CD. Insulin restores neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression and function that is lost in diabetic gastropathy. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:373–384. doi: 10.1172/JCI8273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ordög T, Takayama I, Cheung WK, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Remodeling of networks of interstitial cells of Cajal in a murine model of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes. 2000;49:1731–1739. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.10.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Forster J, Damjanov I, Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Wetzel P, McCallum RW. Absence of the interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with gastroparesis and correlation with clinical findings. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Anitha M, Gondha C, Sutliff R, Parsadanian A, Mwangi S, Sitaraman SV, Srinivasan S. GDNF rescues hyperglycemia-induced diabetic enteric neuropathy through activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:344–356. doi: 10.1172/JCI26295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu M, Seino S, Kirchgessner AL. Identification and characterization of glucoresponsive neurons in the enteric nervous system. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10305–10317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10305.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lam WF, Masclee AA, de Boer SY, Lamers CB. Hyperglycemia reduces gastric secretory and plasma pancreatic polypeptide responses to modified sham feeding in humans. Digestion. 1993;54:48–53. doi: 10.1159/000201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yeap BB, Russo A, Fraser RJ, Wittert GA, Horowitz M. Hyperglycemia affects cardiovascular autonomic nerve function in normal subjects. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:880–882. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.8.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ceriello A, Hanefeld M, Leiter L, Monnier L, Moses A, Owens D, Tajima N, Tuomilehto J. Postprandial glucose regulation and diabetic complications. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2090–2095. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hassan Y, Johnson B, Nader N, Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. The relationship between 24-hour integrated glucose concentrations and % glycohemoglobin. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ishii M, Nakamura T, Kasai F, Baba T, Takebe K. Erythromycin derivative improves gastric emptying and insulin requirement in diabetic patients with gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1134–1137. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Humphreys M. Dietary treatment of diabetes mellitus in the pre-insulin era (1914-1922) Perspect Biol Med. 2006;49:77–83. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2006.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu S, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Franz M, Sampson L, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. A prospective study of dietary glycemic load, carbohydrate intake, and risk of coronary heart disease in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1455–1461. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Stein TP. Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:403–411. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-6-200503150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gutierrez M, Akhavan M, Jovanovic L, Peterson CM. Utility of a short-term 25% carbohydrate diet on improving glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17:595–600. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Farnsworth E, Luscombe ND, Noakes M, Wittert G, Argyiou E, Clifton PM. Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:31–39. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, Williams T, Williams M, Gracely EJ, Stern L. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2074–2081. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stern L, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, Williams M, Gracely EJ, Samaha FF. The effects of low-carbohydrate versus conventional weight loss diets in severely obese adults: one-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:778–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ, Neil BJ, Westphal SA. The insulin and glucose responses to meals of glucose plus various proteins in type II diabetic subjects. Metabolism. 1988;37:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ, Saeed A, Jordan K, Hoover H. An increase in dietary protein improves the blood glucose response in persons with type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:734–741. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wolever TM. The glycemic index. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1990;62:120–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2414–2423. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Björck I, Elmståhl HL. The glycaemic index: importance of dietary fibre and other food properties. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:201–206. doi: 10.1079/pns2002239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mourot J, Thouvenot P, Couet C, Antoine JM, Krobicka A, Debry G. Relationship between the rate of gastric emptying and glucose and insulin responses to starchy foods in young healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:1035–1040. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.4.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hallfrisch J, Facn KM. Mechanisms of the effects of grains on insulin and glucose responses. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19:320S–325S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wolever TM. Relationship between dietary fiber content and composition in foods and the glycemic index. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:72–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Benini L, Castellani G, Brighenti F, Heaton KW, Brentegani MT, Casiraghi MC, Sembenini C, Pellegrini N, Fioretta A, Minniti G. Gastric emptying of a solid meal is accelerated by the removal of dietary fibre naturally present in food. Gut. 1995;36:825–830. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cherbut C, Bruley des Varannes S, Schnee M, Rival M, Galmiche JP, Delort-Laval J. Involvement of small intestinal motility in blood glucose response to dietary fibre in man. Br J Nutr. 1994;71:675–685. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Leclère CJ, Champ M, Boillot J, Guille G, Lecannu G, Molis C, Bornet F, Krempf M, Delort-Laval J, Galmiche JP. Role of viscous guar gums in lowering the glycemic response after a solid meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:914–921. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jones KL, MacIntosh C, Su YC, Wells F, Chapman IM, Tonkin A, Horowitz M. Guar gum reduces postprandial hypotension in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:162–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Blackburn NA, Redfern JS, Jarjis H, Holgate AM, Hanning I, Scarpello JH, Johnson IT, Read NW. The mechanism of action of guar gum in improving glucose tolerance in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1984;66:329–336. doi: 10.1042/cs0660329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.O'Donovan D, Feinle-Bisset C, Chong C, Cameron A, Tonkin A, Wishart J, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Intraduodenal guar attenuates the fall in blood pressure induced by glucose in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:940–946. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.7.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nilsson M, Stenberg M, Frid AH, Holst JJ, Björck IM. Glycemia and insulinemia in healthy subjects after lactose-equivalent meals of milk and other food proteins: the role of plasma amino acids and incretins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1246–1253. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Anderson GH, Woodend D. Effect of glycemic carbohydrates on short-term satiety and food intake. Nutr Rev. 2003;61:S17–S26. doi: 10.1301/nr.2003.may.S17-S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Roberts SB. Glycemic index and satiety. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Uusitupa MI. Fructose in the diabetic diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:753S–757S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.3.753S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Vozzo R, Baker B, Wittert GA, Wishart JM, Morris H, Horowitz M, Chapman I. Glycemic, hormone, and appetite responses to monosaccharide ingestion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2002;51:949–957. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Rayner CK, Park HS, Wishart JM, Kong M, Doran SM, Horowitz M. Effects of intraduodenal glucose and fructose on antropyloric motility and appetite in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R360–R366. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Miller JC. Importance of glycemic index in diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:747S–752S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.3.747S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Heilbronn LK, Noakes M, Clifton PM. The effect of high- and low-glycemic index energy restricted diets on plasma lipid and glucose profiles in type 2 diabetic subjects with varying glycemic control. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:120–127. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Brand-Miller J, Hayne S, Petocz P, Colagiuri S. Low-glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2261–2267. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Schwartz JG, Guan D, Green GM, Phillips WT. Treatment with an oral proteinase inhibitor slows gastric emptying and acutely reduces glucose and insulin levels after a liquid meal in type II diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:255–262. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Berry MK, Russo A, Wishart JM, Tonkin A, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Effect of solid meal on gastric emptying of, and glycemic and cardiovascular responses to, liquid glucose in older subjects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G655–G662. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00163.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Horowitz M, Jones K, Edelbroek MA, Smout AJ, Read NW. The effect of posture on gastric emptying and intragastric distribution of oil and aqueous meal components and appetite. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:382–390. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90711-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Cunningham KM, Read NW. The effect of incorporating fat into different components of a meal on gastric emptying and postprandial blood glucose and insulin responses. Br J Nutr. 1989;61:285–290. doi: 10.1079/bjn19890116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Gentilcore D, Chaikomin R, Jones KL, Russo A, Feinle-Bisset C, Wishart JM, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2062–2067. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Samsom M, Szarka LA, Camilleri M, Vella A, Zinsmeister AR, Rizza RA. Pramlintide, an amylin analog, selectively delays gastric emptying: potential role of vagal inhibition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G946–G951. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.6.G946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Thompson RG, Pearson L, Kolterman OG. Effects of 4 weeks' administration of pramlintide, a human amylin analogue, on glycaemia control in patients with IDDM: effects on plasma glucose profiles and serum fructosamine concentrations. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1278–1285. doi: 10.1007/s001250050821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Thompson RG, Pearson L, Schoenfeld SL, Kolterman OG. Pramlintide, a synthetic analog of human amylin, improves the metabolic profile of patients with type 2 diabetes using insulin. The Pramlintide in Type 2 Diabetes Group. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:987–993. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ratner RE, Dickey R, Fineman M, Maggs DG, Shen L, Strobel SA, Weyer C, Kolterman OG. Amylin replacement with pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycaemic and weight control in Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year, randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2004;21:1204–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Hollander PA, Levy P, Fineman MS, Maggs DG, Shen LZ, Strobel SA, Weyer C, Kolterman OG. Pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy improves long-term glycemic and weight control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:784–790. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chapman I, Parker B, Doran S, Feinle-Bisset C, Wishart J, Strobel S, Wang Y, Burns C, Lush C, Weyer C, et al. Effect of pramlintide on satiety and food intake in obese subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48:838–848. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1732-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Bischoff H. Pharmacology of alpha-glucosidase inhibition. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24 Suppl 3:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Seifarth C, Bergmann J, Holst JJ, Ritzel R, Schmiegel W, Nauck MA. Prolonged and enhanced secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 (7-36 amide) after oral sucrose due to alpha-glucosidase inhibition (acarbose) in Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1998;15:485–491. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199806)15:6<485::AID-DIA610>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Ranganath L, Norris F, Morgan L, Wright J, Marks V. Delayed gastric emptying occurs following acarbose administration and is a further mechanism for its anti-hyperglycaemic effect. Diabet Med. 1998;15:120–124. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199802)15:2<120::AID-DIA529>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hücking K, Kostic Z, Pox C, Ritzel R, Holst JJ, Schmiegel W, Nauck MA. alpha-Glucosidase inhibition (acarbose) fails to enhance secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 (7-36 amide) and to delay gastric emptying in Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2005;22:470–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]