Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s in an APOE3-Christchurch homozygote: a case report (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2020 May 4.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Med. 2019 Nov 4;25(11):1680–1683. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0611-3

Abstract

We identified a PSEN1 mutation carrier from the world’s largest autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease kindred who did not develop mild cognitive impairment until her seventies, three decades after the expected age of clinical onset. She had two copies of the APOE3 Christchurch (R136S) mutation, unusually high brain amyloid, and limited tau/tangle and neurodegenerative measurements. Our findings have implications for APOE’s role in the pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-causing mutation carriers who remain cognitively unimpaired until older ages could help in the discovery of risk-reducing genes. We have identified about 1,200 Colombian Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) E280A mutation carriers from the world’s largest known autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD) kindred1. While there is some variability in the age at clinical onset and disease course, as reported for other ADAD pedigrees,2–5 the kindred’s carriers develop mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia at the respective median ages of 44 (95% CI, 43–45) and 49 (95% CI, 49–50) years6. One mutation carrier did not develop MCI until her seventies, nearly three decades after the typical age of onset. Here, we describe her clinical and biomarker findings, identify a potentially protective gene variant, and consider implications for the understanding, treatment and prevention of AD.

The subject’s pedigree is shown in Extended Data 1. Exact age and other identifying information are omitted to protect her anonymity. She was confirmed to have the amyloid-β42 (Aβ42)-overproducing PSEN1 E280A mutation, described by family informants to be cognitively unimpaired until her seventies, and subsequently met criteria for MCI. Her memory deficits were limited to recent events and her neurological exams were normal. The Supplementary Table 1 shows relative stability in cognitive performance during a 24-month assessment period. Due to our partial reliance on informant reports, it is not possible to confirm whether her resistance to AD dementia is due to delayed MCI onset, prolonged MCI duration, or a combination of both.

Whole exome sequencing corroborated her PSEN1 E280A mutation and discovered that she had two copies of the rare Christchurch (APOEch)7 mutation (an arginine-to-serine substitution at amino acid 136, corresponding to codon 154) in APOE3. Sanger DNA sequencing confirmed the latter finding (Extended Data 2). Whole genome sequencing and a Genomizer8 analysis were used to comprehensibly identify and rank all potentially significant rare and common variants, confirm the PSEN1 E280A mutation as her primary risk factor, and identify APOE3ch homozygosity as her most likely genetic modifier. Single cell RNA sequencing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells confirmed allele-specific expression of her PSEN1 E280A mutation (Supplementary Table 2 & Supplementary Table 3). We were unable to identify any additional homozygote carriers of the ApoE3ch that also carry the PSEN1 E280A variant. In a post hoc analysis of 117 kindred members,9 6% had one copy of this otherwise rare APOE3ch mutation (all closely related individuals), including four PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers who progressed to MCI at the mean age of 45. We thus postulate that APOE3ch homozygosity is required to postpone the clinical onset of ADAD.

APOE, the major susceptibility gene for late-onset AD, has three common alleles (APOE2, 3, and 4). Compared to the most common APOE3/3 genotype, which is considered neutral with regard to AD risk, APOE2 is associated with a lower AD risk and older age at dementia onset, and each additional copy of APOE4 is associated with a higher risk and younger age at onset.10 Carriers of APOEch and other rare mutations in APOE’s low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) binding region commonly have hyperlipoproteinemia type III (HLP-III), similar to that observed in 5–10% of APOE2 homozygotes11. The subject had a history of dyslipidemia treated with atorvastatin 40 mgs per day. While not previously diagnosed, the participant was confirmed to have HLP-III, including APOEch and elevated triglyceride and total cholesterol levels (Supplementary Table 4). Upon diagnosis, the atorvastatin dose was raised to 80 mgs per day and ezetimibe 10 mgs per day was prescribed.

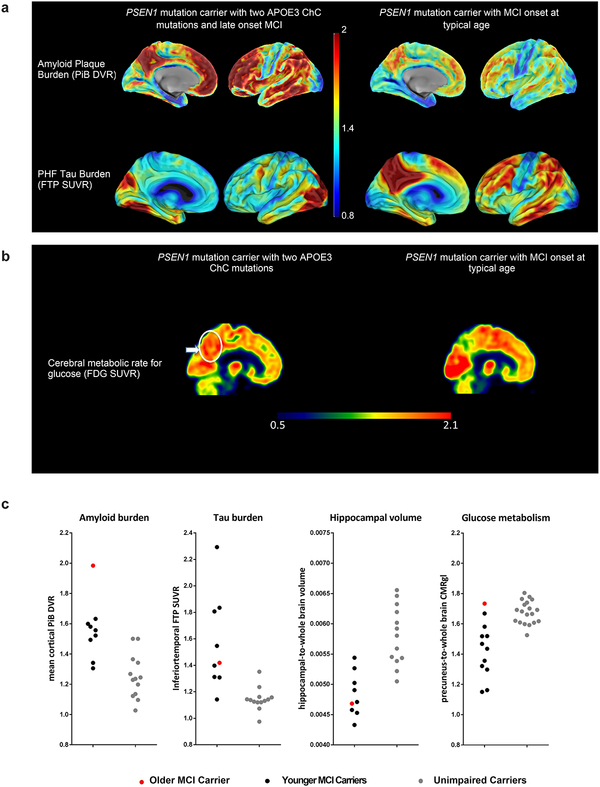

Neuroimaging measurements were used to clarify whether the participant’s resistance to clinical onset of AD was associated with relatively little fibrillar Aβ plaque burden despite more than seventy years of Aβ42 overproduction or with relatively high Aβ plaque burden but limited downstream measurements of paired helical filament (PHF) tau (neurofibrillary tangle burden) and neurodegeneration. The participant’s neuroimaging findings are shown in Figure 1. She had unusually high positron emission tomography (PET) measurements of Aβ plaque burden, as indicated by a higher mean cortical-to-cerebellar Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) distribution volume ratio (DVR=1.96) than in PSEN1 E280A carriers who developed MCI in their forties (DVRs 1.49–1.60). Despite her high Aβ plaque burden, the magnitude and/or spatial extent of her PHF tau burden and neurodegeneration were relatively limited, particularly for her older age: Her flortaucipir (tau) PET measurements were restricted to medial temporal and occipital regions with relative sparing of other regions that are characteristically affected in the clinical stages of AD (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Brain imaging shows limited tau pathology and neurodegeneration despite high amyloid-β plaque burden in an individual homozygous for APOE3ch.

A, PET measurements of amyloid plaque burden (top row, PiB DVRs) and PHF tau (bottom row, flortaucipir standard uptake value ratios (FTP SUVRs). PET images are superimposed onto the medial and lateral surfaces of the left hemisphere. Color-coded scale bar indicates PiB DVR or FTP SUVR values; blue represents lowest binding and red represents highest binding, ranging from 0.8 to 2.0. The APOE3ch homozygote (left panels) had greater amyloid-β plaque burden and relatively limited PHF tau burden, particularly for her age, compared to PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers with MCI at the kindred’s typical age of 44 years. In line with institutional review board regulations, PET imaging measurements were not repeated within short time intervals. B, 18F-fludeoxyglucose (FDG) PET precuneus cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRgl) images are shown. Color-coded scale bar indicates FDG SUVR values; blue represents lowest values and red represents highest values, ranging of 0.5 to 2.1. The arrow and circle indicate that the individual homozygous for APOE3ch had relatively preserved CMRgl in a precuneus/posterior cingulate region known to be preferentially affected by Alzheimer’s disease. ChC, Christchurch. C, Brain imaging measurements of mean cortical amyloid plaque burden, inferior temporal cortex PHF tau burden, hippocampal volume, and precuneus glucose metabolism in the PSEN1 E280A mutation carrier with two APOE3ch alleles and exceptionally late onset of MCI (red dots), PSEN1 mutation carriers with MCI onset at the kindred’s typical, younger age (black dots) and PSEN1 mutation carriers who have not yet developed MCI (gray dots). Amyloid plaque burden is expressed as mean cortical-to-cerebellar distribution volume ratios (DVRs). Paired helical filament (PHF) tau burden is expressed as inferior temporal-to-cerebellar FTP SUVRs. Hippocampal volumes are expressed as hippocampal-to-whole brain volume ratios. Cerebral glucose metabolism is reflected as precuneus-to-whole-brain CMRgl ratios. While the PSEN1 E280A mutation carrier with two APOE3ch alleles had by far the highest amyloid plaque burden, she did not have comparably severe PHF tau burden or hippocampal atrophy, and she had no evidence of precuneus glucose hypometabolism.

The subject’s fluorodeoxyglucose PET measurements of the cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRgl, Figure 1b) were preserved in brain regions that are known to be preferentially affected by AD, including higher precuneus-to-whole brain glucose metabolism than PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers who developed MCI at younger ages. Her MRI-based hippocampal-to-whole brain volume, an atrophy measurement that can be affected by AD and/or normal aging, was within the range of mutation carriers who developed MCI in their forties (Figure 1c). She also had relatively low plasma neurofilament light chain (NfL) measurements (20.24 pg/mL), a blood marker of axonal injury and neurodegeneration12 related to familial AD, particularly for her older age (her result and the mean and standard deviation of non-mutation carriers in the same age range, data not shown). Our findings suggest that this APOE3ch homozygote’s resistance to the clinical onset of AD is mediated through a mechanism that limits tau pathology and neurodegeneration even in the face of high Aβ plaque burden.

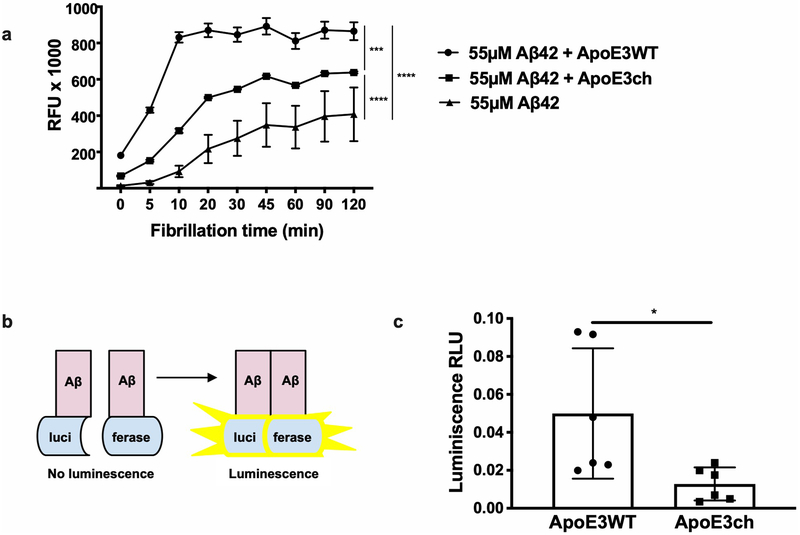

To study the APOE3ch variant’s functional consequences, we compared Aβ42 aggregation in vitro in the presence of human recombinant ApoE3 protein, presence of ApoE3ch protein, and absence of ApoE. Aβ42 aggregation was highest in the presence of human ApoE3 protein (C-terminus domain), lower in the presence of human ApoE3ch (similar to that observed in the presence of ApoE213), and lowest in the absence of any ApoE (Extended Data 3). This finding was confirmed using a split-luciferase complementation assay sensitive to the characterization of potentially neurotoxic Aβ42 oligomers13. These in vitro results showing lower ability of the ApoE3ch to trigger Aβ42 aggregation suggest that the subject may have had even greater Aβ plaque deposition had she survived to her seventies without the APOE3ch/3ch genotype.

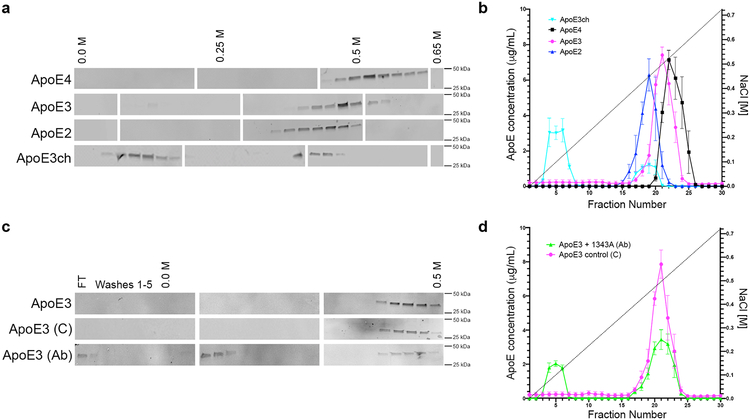

The R136S mutation is located in a region of APOE known to play a role in binding to lipoprotein receptors and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG)11. Previous reports showed that compared to ApoE3, ApoE2 and ApoE3ch are associate with a 98% and 60% reductions in LDLR binding, respectively11,14. HSPG has been suggested to promote Aβ aggregation and neuronal uptake of extracellular tau; and ApoE-binding may be necessary for some of these effects15,16. Our analyses of heparin binding showed that ApoE4 had higher affinity for heparin compared to ApoE3 and ApoE217. We also found that compared to other ApoE isoforms, ApoE3ch displayed the lowest heparin binding ability (Figure 2). We then raised a monoclonal antibody (1343A) against ApoE amino acids 130–143 (including R136S) and demonstrated its ability to reduce wild type ApoE3 heparin binding to that associated with the ApoE3ch protein in vitro (Figure 2). These studies suggest that antibodies or other molecules binding to this ApoE region or modulating ApoE-HSPG interactions could reproduce this potentially protective effect of ApoE3ch.

Figure 2. The Christchurch mutation impairs ApoE’s heparin binding.

(A, C) We used western blotting to detect ApoE in protein fractions eluted from heparin columns using an increasing NaCl gradient. Individual blots were cropped between 25 to 50 kDa. Blank spaces separate individual blots that are representative of n = 2 independent experiments. FT = flow through. (B, D) We used ELISA to quantify differences in the NaCl elution pattern of different ApoE isoforms from heparin columns. N = 3 columns per isoform in independent experiments were analyzed side-by-side twice on different days to quantify differences. Error bars depict standard error of mean. In (B) ApoE2 is depicted in blue; ApoE3, magenta; ApoE4, black; and, ApoE3ch, cyan. In (D) wild type ApoE3 in the presence of an ApoE-specific antibody (1343A) is depicted in green whereas control is shown in magenta. ApoE3ch was eluted from the heparin column with the lowest NaCl concentration revealing impaired heparin binding compared to other ApoE isoforms (A, C). Wild type ApoE3 was also eluted with low NaCl concentrations when incubated with an antibody specific for an HSPG-binding domain of ApoE (B, D).

We describe a homozygous APOE3ch subject remarkably resistant to the clinical onset of ADAD dementia. Our data support a model in which APOE variants differ in the extent of their pathogenic functions (APOE3ch and APOE2<3<4) and APOE3ch and APOE2 are associated with greatest functional loss. We postulate that APOE3ch exerts beneficial effects on downstream tau pathology and neurodegeneration, even in the face of high Aβ plaque burden, and that the beneficial effect is related, in part, to altered affinity for HSPG or other ApoE receptors. While this mutation may not be deterministic, our data strongly suggest that APOE3ch is not neutral to the AD phenotype as it would be expected for the wild type APOE3. APOE3ch is the best candidate that we can clearly identify as a genetic modifier in this subject and fully recognize that other factors could have played a role to achieve such strong resistance phenotype. We postulate that interventions that safely and sufficiently edit APOE, lower its expression, or modulate its pathogenic functions related to HSPG interactions could have a profound impact on the treatment and prevention of AD.

Methods

Clinical assessments

Institutional review boards from the University of Antioquia, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Schepens Eye Research Institute of Massachusetts Eye and Ear approved this study. Like all of the research participants, the proband case provided her informed consent. Clinical ratings and neuropsychological tests were performed as noted in Supplementary Table 1.

All clinical measures were undertaken at the University of Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia) and were conducted in Spanish by physicians and psychologists trained in assessment. Neurocognitive testing included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), and a Spanish version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease battery, which have been adapted to this Colombian population18. Additional testing consisted of the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale and the Functional Assessment Staging test, which were done before imaging.

Additional studies were conducted after the PSEN1 E280A mutation carrier was discovered to have two copies of the APOE3ch variant. A fasting serum lipid panel was performed to explore the possibility of hyperliproteinemia type III (Supplementary table 4), a condition found in 5–10% of persons homozygous for the relatively AD protective APOE2 allele and in most but not all APOE3ch carriers19. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Whole exome sequencing

Whole-exome capture and sequencing were performed using Illumina chemistry for variant discovery; rare variants with less than 1% frequency in genes previously associated with AD were considered in the search for candidate risk modifiers. Specifically, we identified rare DNA variants (minor allele frequency <1%) within exonic regions and splice-site junctions (5 bp into introns) of genes using bioinformatics tools. We constructed and sequenced whole exome libraries on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer with the use of 151 bp paired-end reads. Library construction was performed using a previously described protocol20 modified as follows. Genomic DNA input was reduced from 3 μg to 50 ng in 10 μL of solution and enzymatically sheared. Dual-indexed Illumina paired end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8 base index sequences embedded within the adapter and added to each end for adapter ligation. We performed in-solution hybrid selection using the Illumina Rapid Capture Exome enrichment kit with 38Mb target territory (29Mb baited). The targeted region included 98.3% of the intervals in the Refseq exome database. Dual-indexed libraries were pooled into groups of up to 96 samples prior to hybridization. The enriched library pools were quantified via PicoGreen after elution from streptavadin beads and then normalized. For cluster amplification and sequencing, the libraries prepared using forked, indexed adapters were quantified using quantitative PCR (KAPA biosystems), normalized to 2 nM using Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system, and pooled with equal volume using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system. Pools were then denatured in 0.1 N NaOH. Denatured samples were diluted into strip tubes using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system. Cluster amplification of the templates was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina) using the Illumina cBot. Flowcells were sequenced on HiSeq 4000 Sequencing-by-Synthesis Kits, then analyzed using RTA2.7.3

Exome sequencing data was processed and analyzed with the bioinformatics pipeline of the Center’s Clinical Exome Sequencing of the Center for Personalized Medicine (CPM) Clinical Genomics Laboratory and the Translational Genomics Research Institute. Briefly, we used Edico Genome’s Dragen Genome Pipeline with default parameters to perform sequence alignment and variant calling. We used the open source software samtools and bcftools (https://samtools.github.io/) along with a set of custom scripts to perform coverage determination and initial variant filtering based on ExAC (Exome Aggregation Consortium, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) allele frequencies. Sequence alignment was done against the Human hs37d5 decoy genome. To identify the potential modifier variants, a primary gene list of 15 genes was generated based on two HPO terms: HP:0002511, Alzheimer disease; HP:0003584, Late onset. These genes were AAGAB, ABCC8, AKT2, APOE, APP, BEAN1, GATA1, GCK, HMGA1, HNF1B, HNF4A, LDB3, PAX4, PSEN1, and PSEN2. Rare DNA variants (minor allele frequency <1%) within exonic regions and splice-site junctions (5 bp into introns) of these genes were further annotated and analyzed using a commercial tool (Cartagenia v5.0). Sequence alterations were reported according to the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS v2.0) nomenclature guidelines. The subject did not have other mutations in PSEN1, amyloid precursor protein (APP), tau genes or in the chemokine gene cluster suggested to be associated with an older onset age in this kindred19. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Whole genome sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and a Genomizer analysis (v 10.1.0) were used to conduct a comprehensive and unbiased ranking of other potential genetic risk modifiers, including those associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer’s dementia, helping to exclude other potentially protective genetic factors10. For processing the WGS data, the same dragen pipeline described above was used. The data was aligned to the GRCh37 decoy genome (hs37d5). Variants that were called at a depth of <10X were filtered out and then were annotated using Ensembl’s Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) tool. The version of VEP using was v93. The filtered and annotated set of variants was then compiled for Genomizer analysis. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

APOE Genotyping by Sanger sequencing

Reaction mixture for the amplification process was performed in a 50 μL volume that included the following components: 1xPfuUltra II Hostart Master Mix, 1μL of each primer (10 μmol/L)(Forward primer: 5’- AGCCCTTCTCCCCGCCTCCCACTGT-3’ and Reverse primer: 5’- CTCC GCCACCTGCTCCTTCACCTCG-3’), 5% DMSO and 1μL of genomic DNA (100 ng/μL)21. PCR cycling was run with initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 40 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction kit from Qiagen and sequenced by MGH CCIB DNA core using the 3730xl sequencer from Applied Biosystems. To avoid errors in sampling the blood sample used for Sanger sequencing was different from the sample used for the WGS analysis. Genotyping of four descendants of the case were confirmed to be heterozygote carriers of the ApoE3ch as expected when one parent is homozygote (Extended data 2). Data is representative of n = 2 independent experiments and further validated independently with whole exome and whole genome sequencing. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

MRI and PET imaging

Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB), flortaucipir (FTP) positron emission tomography (PET) and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements were acquired at Massachusetts General Hospital and analyzed at Massachusetts General Hospital and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute as previously described2. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET images were acquired at the University of Antioquia, Colombia, and analyzed as previously described22. Imaging data from the case were compared to those from younger PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers who developed MCI at the kindred’s expected age at clinical onset, and from mutation carriers who were cognitively unimpaired.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on a 3 Tesla Tim Trio (Siemens) and included a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) processed with Freesurfer (FS) to identify grey white and pial surfaces to permit regions of interest (ROI) parcellation as follows: cerebellar grey, hippocampus, and the following Braak Stage related cortices: entorhinal, parahippocampal, inferior temporal, fusiform, posterior cingulate, as described previously23–26.

18F-Flortaucipir (FTP) for positron emission tomography (PET) was prepared at MGH with a radiochemical yield of 14±3% and specific activity of 216±60 GBq/μmol at the end of synthesis (60 min), and validated for human use27. 18F-FTP PET was acquired from 80–100 minutes after a 9.0 to 11.0 mCi bolus injection in 4 × 5-minute frames. 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B (11C PiB) PET images were prepared and images acquired as previously described23 using a Siemens/CTI (Knoxville, TN) ECAT HR+ scanner (3D mode; 63 image planes; 15.2cm axial field of view; 5.6mm transaxial resolution and 2.4mm slice interval. 11C PiB PET was acquired with a 8.5 to 15 mCi bolus injection followed immediately by a 60-minute dynamic acquisition in 69 frames (12×15 seconds, 57×60 seconds). PET images were reconstructed and attenuation-corrected, and each frame was evaluated to verify adequate count statistics and absence of head motion.

18F FTP specific binding was expressed in FS ROIs as the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) to cerebellum, similar to a previous report26, using the FS cerebellar grey ROI as reference. For voxelwise analyses, each subject’s MPRAGE was registered to the template MR in SPM8 (SPM), and the spatially transformed SUVR PET data was smoothed with a 8 mm Gaussian kernel to account for individual anatomic differences28. To account for possible 18F FTP off-target binding in choroid plexus, which may confound hippocampal signal, we used a linear regression to regress the choroid plexus, as previously reported29.

11C PiB PET data were expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR) with cerebellar grey as reference tissue; regional time-activity curves were used to compute regional DVRs for each ROI using the Logan graphical method applied to data from 40 to 60 minutes after injection23,30. 11C PiB retention was assessed using a large cortical ROI aggregate that included frontal, lateral temporal and retrosplenial cortices (FLR) as described previously31,32.

18F-fludeoxyglucose PET was performed on a 64-section PET/computed tomography imaging system (Biograph mCT; Siemens) using intravenous administration of 5 mCi (185 million Bq) of 18F-fludeoxyglucose after a 30-minute radiotracer uptake period when resting in a darkened room, followed by a 30-minute dynamic emission scan (six 5-minute frames). Images were reconstructed with computed tomographic attenuation correction.

Precuneus to whole-brain cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRgl) ratios were characterized from a bilateral region of interest (ROI) in each participant’s 18F-fludeoxyglucose PET image using an automated brain mapping algorithm (SPM8; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8). Hippocampal to total intracranial volume ratios were characterized from bilateral ROIs in each participant’s T1-weighted MR image using FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). All images were visually inspected to verify ROI characterization. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Plasma NfL assay

For NfL analysis, plasma was shipped on dry ice to the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden. NfL concentration was measured using an in house Single molecule array (Simoa) assay, as previously described in detail33. The measurements were performed by board-certified laboratory technicians who were masked to clinical and genetic data. For a quality control (QC) sample with a concentration 11.7 pg/mL, repeatability was 8.02% and intermediate precision was 20.2%. For a QC sample with a concentration 182 pg/mL, repeatability was 5.74% and intermediate precision was 8.34%.

Amyloid aggregation studies

Recombinant human ApoE3 protein fragments (including the carboxyl-terminus domain plus a histidine tag; MLGQSTEELRVRLASHLRKLRKRLLRDADDLQKRLAVYQAGAREGAERGLSAIRERLGPLVEQGRVRAATVGSLAGQPLQERAQAWGERLRARMEEMGSRTRDRLDEVKEQVAEVRAKLEEQAQQIRLQAEAFQARLKSWFELPVEDMQRQWAGLVEKVQAAVGTSAAPVPSDNHHHHHH) with and without the Christchurch mutation were produced in bacteria, purified (Innovagen), and used to assess the differential effects of these proteins on Aβ42 aggregation in vitro using Thioflavin T (SensoLyte® ThT β-Amyloid (1–42) Aggregation kit, cat. # AS-72214). 55 μM of Aβ42 was added to solutions of either 10μM wild type ApoE3 or ApoEch (136Arg→Ser) proteins in a transparent, no-binding 96-well plate. Samples were then mixed with 2 mM Thioflavin T dye and fluorescence was read at Ex/Em = 440/484 nm at intermittent time intervals over 2 hours. The plate was kept at 37°C with 15 seconds shaking between reads.

Full-length ApoE3 proteins with and without the Christchurch mutation were also expressed in Flp-In™ T-REx™ 293 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) mammalian cells via transient transfection to confirm the impact of these proteins on Aβ42 aggregation using a previously published split-luciferase complementation assay34 and based on the known toxicity of the oligomeric intermediates of Aβ35. The latter analysis was conducted using the human APOE3 expression from Addgene (Plasmid #8708636) as the WT or APOE3 with the Christchurch variant introduced via site-directed mutagenesis. Reagents for luciferase assay were purchased from Promega. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Heparin-sepharose affinity chromatography

The heparin binding affinity of human full-length, histidine tagged ApoE2, ApoE3 and ApoE4 protein isoforms37 produced in bacteria were compared to ApoE3ch using 1 mL heparin columns (BioVision- 6554-1). The columns were acclimatized to room temperature for 1-hour prior use and washed with 5 mL of 20 mM TRIS-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). 1 mL sample containing 50 μg/mL of recombinant ApoE protein in 20 mM TRIS-HCl (pH7.5) was then recycled through the column 5 times. The column was then washed for 5 times using the same buffer. An increasing gradient of NaCl in 20 mM TRIS-HCl (0.025–1 M, 1 mL per each gradient step) was passed through the column and 1 mL fractions were collected and subsequently analyzed using western blotting and ELISA. We conducted n = 3 independent experiments.

Western blotting (WB)

We used WB to detect ApoE positive fractions collected from the heparin binding columns. Fractions were diluted in 10 μL RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology), 4 μL DTT (1 M, Sigma Aldrich) and 10 μl Laemmli buffer (Boston Bioproducts) to a final volume of 40 μl and denatured 5 min. at 60°C. Samples were separated electrophoretically for 1h at 70 V using 4–20% pre-cast gradient gels (Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™, Bio-Rad) and SDS-Tris-Glycine buffer. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (VWR; 27376–991) for 1 hour at 70 V. Membranes were blocked 1 hour with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE), and probed either 1 h room temperature (R.T.) or over-night at 4°C with anti-his tag antibody (rb, 1:5000, Novus biologicals), and 1 hour R.T. with IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit (1:10000, LI-COR Biosciences) antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System and visualized on the Image Studio version 2.1 (LI-COR Biosciences). A composite of individual gels was used to generate Figure 2. All western blotting reported in Figure 2 are representative of two independent experiments.

ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were carried out using Ni-NTA HisSorb Plates (Qiagen, 35061) to measure ApoE protein isoforms (ApoE2, ApoE3, ApoE3ch and ApoE4) eluted from heparin columns. The fractions were diluted (1:4) in reagent diluent (DY008, R&D Systems) in a final volume of 200 μL. The plates were incubated for 2 hours. The plate was washed five times with wash buffer (DY008, R&D Systems) and incubated with Anti-His tag antibody (1:10,000; Novus biologicals; NBP2–61482) overnight at 4°C. The plate was washed five times with wash buffer (DY008) to ensure removal of unbound primary antibody and incubated with donkey anti-rabbit-HRP (1:10000; NA934V ECL) for 45 minutes. The plate was then washed five times to ensure removal of secondary antibody. We used tetramethylbenzidine (100 μL/well; Millipore) to initiate the colorimetric reaction and sulfuric acid (25 μL/well; DY008 R&D Systems) to terminate the reaction after 5 minutes incubation at room temperature and away from light. The absorbance of samples was then read at 450 nm using the Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments. Inc) and data processed and analyzed using Gen5 1.11 software and GraphPad Prism respectively. N = 3 columns per isoform in independent experiments. Representative data is expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Generation of monoclonal antibodies against ApoE3

We generated monoclonal antibodies against a peptide including the ApoE3ch mutation: KLH-CTEELRVSLASHLRK-CONH2 as fee-for-service from Innovagen (Sweden). A cysteine residue was added at the N-terminus to facilitate conjugation of the peptides. Cell fusions were obtained from positive clones and cell supernatants tested for activity against the wild type and mutant peptides and full-length proteins using ELISA. Antibodies designed against the peptide were tested for their affinity to ApoE3 and ApoEch mutant recombinant proteins using ELISA. The Ni-NTA HisSorb ELISA Plates (Qiagen) were used using the same protocol as previously described on plates coated with 0.5 μg/mL recombinant protein and with the variation of using Anti-ApoE (ms monoclonal; Innovagen; 1:1,000 to 1:32,000 serial dilutions) and secondary antibody rabbit anti mouse-HRP (Abcam; ab97046, 1:10,000) for 45 minutes.

Antibody competition assay

A monoclonal antibody was identified as capable of detecting both the wild type and Christchurch mutant ApoE3 (1343A). The identify of the 1343A antibody was confirmed by RapidNovor (Canada) as fee-for-service. This antibody was incubated with an ApoE3 wild type recombinant protein (50 μg/mL in 20 mM Tris-HCl) at a 1:10 ratio and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature. A negative control containing the cell culture supernatant media only, and a positive control containing the recombinant protein ApoE3 alone were used. The antibody/ApoE3 recombinant protein solution and controls were eluted through heparin columns as previously described. Fractions were collected and analyzed by ELISA and WB.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

PBMCs were isolated from fresh blood in a Ficoll gradient using standard protocols. Concentration and viability of cell samples were measured via hemocytometer using trypan blue (1:2 dilution) exclusion to identify live cells (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Cell concentration ranged from 7 – 12 × 105 cells/mL with 90–95% viability. Sample single cell suspensions were processed using 10× Genomics’ Single Cell 3′ v3 kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions for a targeted recovery of 3,000 cells (10× Genomics, USA). Size distribution and molarity of resulting cDNA libraries were assessed via the Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Assay (Agilent Technologies, USA). All cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 instrument according to Illumina and 10× Genomics guidelines with 1.4–1.5 pM input and 1% PhiX control library spike-in (Illumina, USA) generating over 40M reads per cell. Sequencing basecall data were de-multiplexed and aligned to the hg19 or GRCh37 human reference and transcripts identified were quantified using the Cell Ranger 3.0 software package with default parameters (10X Genomics, USA).

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis

Raw sequencing data from n = 2 runs was processed using the Cell Ranger software suite v3.0.2 in order to perform demultiplexing, barcode processing, transcript counting and clustering analysis. Specifically, we generated gene-barcode matrices per each case’s sequencing data in MEX format, and, subsequently, we performed an aggregated analysis to produce an aggregated gene-barcode matrix (n = 6 cases) using the same software. The raw and filtered gene-barcode (cell) matrices with count data were used as input for Seurat R-package to conduct down-stream analysis. Clustering was performed using Cell Ranger and viewed using Loupe Cell Browser. Cell Ranger secondary analysis and clustering analyses was done on both per case and aggregate data. The per case estimated number of cells ranged from 2,495 to 3,716 for most cases, except for JA_98 (1,179 cells), the total number from all cases is 16,373 cells. The mean reads per cell ranged from 43,470 to 82,240 (Supplementary Table 2). Secondary analysis was carried out using R with Seurat R package38 and other R packages. The feature-barcode matrices were loaded into R using Seurat to enable a wide variety of custom analyses. The gene-cell count data was normalized and scaled with SCTransform algorithm in Seurat R package. RunUMAP was used to perform non-linear dimensional reduction with the UMAP algorithm, to cluster the cells. Each cluster cell type was inferred by checking their marker genes expression profile against know gold standard single cell PBMC blood cell type labels in known PBMC dataset. The per case data was merged together as a whole for joint analysis in R. Further information can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com) and considering a p value less than 0.05 and a α of 0.05 as statistically significant. We used 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test on n = 2 independent experiments (n = 3 technical replicates; F (2, 16) = 76.05; DF = 2; ****p = 0.00000797 for 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3WT vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3ch; ****p = 0.0000000042 for 55 μM Aβ42 vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3WT; ***p = 0.00022 for 55 μM Aβ42 vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3ch) for the statistical analysis of the fibrillation assay (Extended Data 3a). We used the 2-tailed unpaired T-test to analyze data obtained by the split-luciferase Assay (n = 2 independent experiments performed with n = 3 technical replicates; t = 2.758, DF = 1; p = 0.0202; Extended Data 3c). All representative data is presented as mean ± SEM (Figure 2 and Extended Data 3).

Data Availability

Anonymized clinical, genetic, and imaging data are available upon request, subject to an internal review by J.F.A.-V., Y.T.Q., E.M.R., and F.L. to ensure that the participants’ anonymity, confidentiality, and PSEN1 E280A carrier or non-carrier status are protected, completion of a data sharing agreement, and in accordance with University of Antioquia’s and Massachusetts General Hospital’s IRB and institutional guidelines. Experimental data is available upon request, subject to Massachusetts General Hospital and Schepens Eye Research Institute of Mass Eye and Ear institutional guidelines. Material requests and data requests will be considered based on a proposal review, completion of a material transfer agreement and/or a data use agreement, and in accordance with the Massachusetts General Hospital and Schepens Eye Research Institute of Mass Eye and Ear institutional guidelines. Please submit requests for participant-related clinical, genetic, and imaging data and samples to Y.T.Q. (yquiroz@mgh.harvard.edu) and requests for experimental data, DNA and single-cell RNA sequencing data, and antibodies to J.F.A.-V. (joseph_arboleda@meei.harvard.edu).

Extended Data

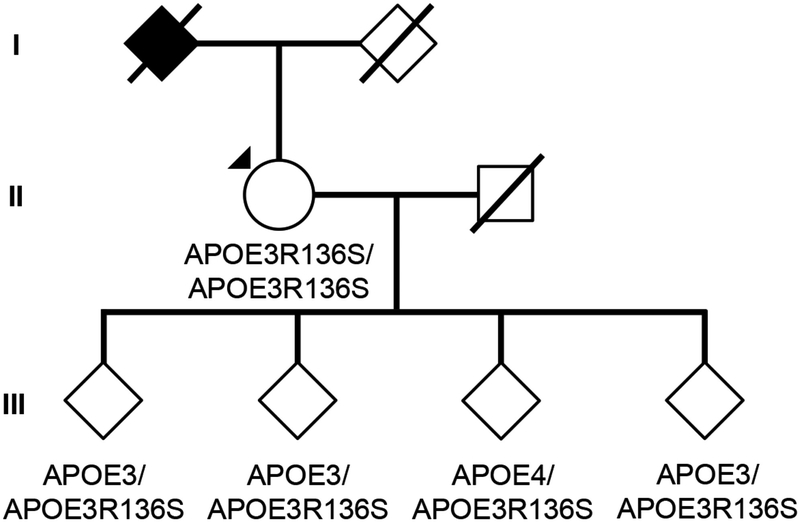

Fig. 1. Subject’s genealogy.

Circles represent females, squares represent males, diamonds represent individuals whose gender has been masked for privacy, arrowhead depicts proband individual with MCI, and shading indicates individual with history of dementia. Deceased individuals are marked with a crossed bar. APOE genotypes are indicated as appropriate to preserve anonymity. Family links were verified by three family informants. Genotypes of relatives of the R136S homozygote individual were determined by Sanger sequencing (Extended Data Figure 2).

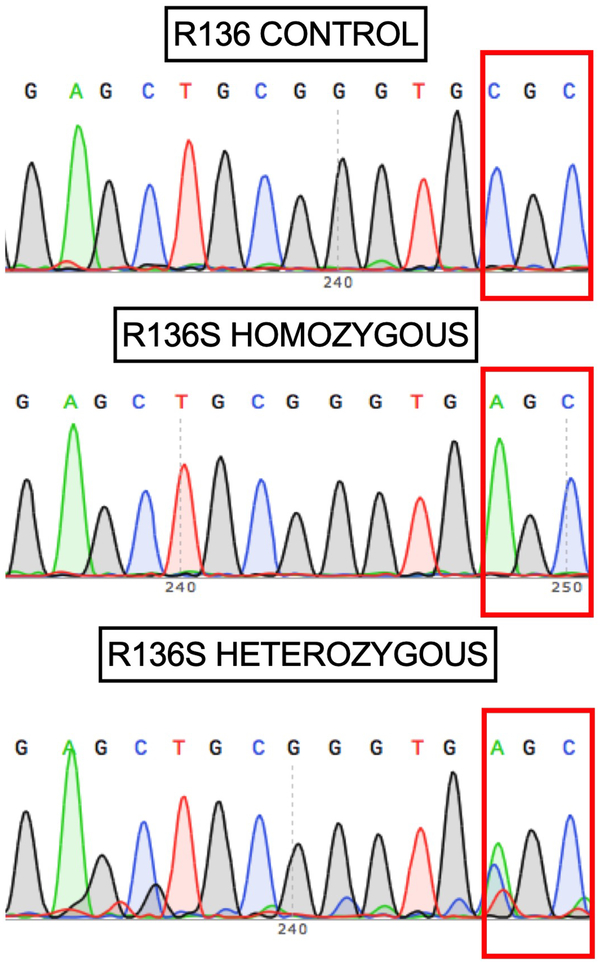

Fig. 2. Sanger DNA sequencing of homozygous ApoEch carrier individual.

Representative direct sequencing results of amplicon in APOE gene from control, proband, and descendants’ samples. R136 homozygous sequence is shown in upper panel from a control individual. In the middle panel, proband case is shown. R136S homozygous mutation can be observed. In bottom panel a R136S heterozygous mutation from a descendant is identified. Data representative of n=2 independent experiments and further validated independently with whole exome and whole genome sequencing.

Fig. 3. ApoE3ch modulates Aβ aggregation.

(A) Rate of Aβ42 fibril formation in the presence of C-terminus fragments of ApoE3 wild-type (WT), APOE3ch, or in the absence of ApoE as detected by Thioflavin T fluorescence. Changes in relative fluorescence units (RFU) were plotted for time in minutes (min). Aβ42 fibrillation rate was lower in the presence of ApoE3ch compared to ApoE3 WT (****p = 0.00000797 for 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3WT vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3ch; ****p = 0.0000000042 for 55 μM Aβ42 vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3WT; ***p = 0.00022 for 55 μM Aβ42 vs. 55 μM Aβ42 + ApoE3ch, 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n=3 represended as mean ± SEM.). (B) Schematic representation of the split-luciferase complementation triggered by amyloid oligomerization in vitro. (C) Percentage of luminescence expressed as relative luminescence units (RLU) was obtained by split-luciferase complementation assay after 24 hours in culture media from 293T cells transfected with full-length ApoE3ch or ApoE3WT cDNA. Luciferase luminescence by oligomer formation is significantly reduced in ApoE3ch compared to ApoE3 WT indicating lower aggregation. (*p = 0.0202, 2-tailed unpaired T-test, n=6). Representative data presented as individual values ± SEM of n=3 independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

1

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Colombian families with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s Disease for making this work possible. This study was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of the Director grant DP5 OD019833 and US National Institute on Aging grant R01 AG054671, Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research, Physician/ Scientist Development Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital, and Alzheimer’s Association Research Grant to Y.T.Q.; US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and National Institute on Aging co-funded grants UH3 NS100121 and RF1 NS110048 to J.F.A.-V.; Grimshaw-Gudewicz Charitable Foundation grant to J.F.A.-V., J.B.M., and L.A.K.; Banner Alzheimer’s Foundation and Nomis Foundation grants to E.M.R. and P.N.T.; Anonymous Foundation grant to E.M.R.; US National Institute on Aging grants R01 AG031581 and P30 AG19610 to E.M.R.; US National Institute on Aging grant RF01 AG057519 to G.R.J.; and State of Arizona grant to E.M.R. We also thank A. Koutoulas for technical support with DNA sequencing, B. Hyman from Massachusetts General Hospital for providing expression plasmids for the split-luciferase complementation assay, and Y. Alekseyev, A. LeClerc, M.J. Mistretta, J. Horvath and J. Campbell from the Boston University Department of Medicine Single Cell Sequencing Core and Boston University Microarray and Sequencing Resource Core Facilities for reagents and technical support for single cell RNA sequencing.

Footnotes

Competing interests

P.N.T. has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on scientific advisory boards, or other activities with AbbVie, AC Immune, Acadia, Auspex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chase Pharmaceuticals, Corium, Eisai, GliaCure, INSYS Therapeutics, Pfizer, T3D, AstraZeneca, Avanir, Biogen, Eli Lilly, H. Lundbeck A/S, Merck and Company, and Roche; holds a provisional patent on “Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease” at the University of Rochester; holds stock options in Adamas; received research support from AstraZeneca, Avanir, Biogen, Eli Lilly, H. Lundbeck A/S, Merck and Company, Roche, Amgen, Avid, Functional Neuromodulation, GE Healthcare, Genentech, Novartis, Takeda, Targacept, the National Institute on Aging, and the Arizona Department of Health Services. H.Z. has served at scientific advisory boards for Roche Diagnostics, Wave, Samumed and CogRx, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Biogen and Alzecure, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg (outside submitted work). R.A.S. has received personal compensation from AC Immune, Eisai, Roche, and Takeda, and research grant support from Eli Lilly and Janssen. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References:

- 1.Quiroz YT, et al. Association Between Amyloid and Tau Accumulation in Young Adults With Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 75, 548–556 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llado A, et al. A novel PSEN1 mutation (K239N) associated with Alzheimer’s disease with wide range age of onset and slow progression. Eur J Neurol 17, 994–996 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thordardottir S, et al. Reduced penetrance of the PSEN1 H163Y autosomal dominant Alzheimer mutation: a 22-year follow-up study. Alzheimers Res Ther 10, 45 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight WD, et al. Pure progressive amnesia and the APPV717G mutation. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23, 410–414 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velez JI, et al. APOE*E2 allele delays age of onset in PSEN1 E280A Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry 21, 916–924 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acosta-Baena N, et al. Pre-dementia clinical stages in presenilin 1 E280A familial early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 10, 213–220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wardell MR, Brennan SO, Janus ED, Fraser R & Carrell RW Apolipoprotein E2-Christchurch (136 Arg----Ser). New variant of human apolipoprotein E in a patient with type III hyperlipoproteinemia. J Clin Invest 80, 483–490 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smedley D, et al. A Whole-Genome Analysis Framework for Effective Identification of Pathogenic Regulatory Variants in Mendelian Disease. Am J Hum Genet 99, 595–606 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalli MA, et al. Whole-genome sequencing suggests a chemokine gene cluster that modifies age at onset in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry 20, 1294–1300 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corder EH, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet 7, 180–184 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahley RW, Huang Y & Rall SC Jr. Pathogenesis of type III hyperlipoproteinemia (dysbetalipoproteinemia). Questions, quandaries, and paradoxes. J Lipid Res 40, 1933–1949 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preische O, et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 25, 277–283 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto T, et al. Apolipoprotein E, especially apolipoprotein E4, increases the oligomerization of amyloid beta peptide. J Neurosci 32, 15181–15192 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalazar A, et al. Site-specific mutagenesis of human apolipoprotein E. Receptor binding activity of variants with single amino acid substitutions. J Biol Chem 263, 3542–3545 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauch JN, et al. Tau Internalization is Regulated by 6-O Sulfation on Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs). Sci Rep 8, 6382 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smedley D, et al. A Whole-Genome Analysis Framework for Effective Identification of Pathogenic Regulatory Variants in Mendelian Disease. American Journal of Human Genetics 99, 595–606 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamauchi Y, et al. Role of the N- and C-terminal domains in binding of apolipoprotein E isoforms to heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate: a surface plasmon resonance study. Biochemistry 47, 6702–6710 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguirre-Acevedo DC, et al. Validity and reliability of the CERAD-Col neuropsychological battery. Validez y fiabilidad de la batería neuropsicológica CERAD-Col 45, 655–660 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahley RW, Huang Y & Rall SC Pathogenesis of type III hyperlipoproteinemia (dysbetalipoproteinemia). Questions, quandaries, and paradoxes. Journal of lipid research 40, 1933–1949 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher S, et al. A scalable, fully automated process for construction of sequence-ready human exome targeted capture libraries. Genome Biology 12, R1 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong L, et al. A rapid and cost-effective method for genotyping apolipoprotein e gene polymorphism. Molecular Neurodegeneration 11, 2 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleisher AS, et al. Associations between biomarkers and age in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease kindred: A cross-sectional study. JAMA Neurology 72, 316–324 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker JA, et al. Amyloid-β associated cortical thinning in clinically normal elderly. Annals of Neurology 69, 1032–1042 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braak H & Braak E Diagnostic criteria for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, S85–88 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braak H, Rüb U, Schultz C & Tredici KD Vulnerability of cortical neurons to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 9, 35–44 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson KA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Annals of Neurology 79, 110–119 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoup TM, et al. A concise radiosynthesis of the tau radiopharmaceutical, [18F]T807. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals 56, 736–740 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chien DT, et al. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F18]-T808. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 34, 457–468 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, et al. Evaluation of Tau imaging in staging Alzheimer disease and revealing interactions between β-Amyloid and tauopathy. JAMA Neurology 73, 1070–1077 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logan J Graphical analysis of PET data applied to reversible and irreversible tracers. Nuclear Medicine and Biology (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amariglio RE, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns, amyloid-b, and neurodegeneration in clinically normal elderly. Neurology 85, 56–62 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedden T, et al. Disruption of Functional Connectivity in Clinically Normal Older Adults Harboring Amyloid Burden. Journal of Neuroscience 29, 12686–12694 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gisslén M, et al. Plasma Concentration of the Neurofilament Light Protein (NFL) is a Biomarker of CNS Injury in HIV Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. EBioMedicine 3, 135–140 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto T, et al. Apolipoprotein E, Especially Apolipoprotein E4, Increases the Oligomerization of Amyloid Peptide. Journal of Neuroscience 32, 15181–15192 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudry E, et al. Gene transfer of human Apoe isoforms results in differential modulation of amyloid deposition and neurotoxicity in mouse brain. Sci Transl Med 5, 212ra161 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Futamura M, et al. Two-step mechanism of binding of apolipoprotein E to heparin: Implications for the kinetics of apolipoprotein E-heparan sulfate proteoglycan complex formation on cell surfaces. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280, 5414–5422 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E & Satija R Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature biotechnology 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized clinical, genetic, and imaging data are available upon request, subject to an internal review by J.F.A.-V., Y.T.Q., E.M.R., and F.L. to ensure that the participants’ anonymity, confidentiality, and PSEN1 E280A carrier or non-carrier status are protected, completion of a data sharing agreement, and in accordance with University of Antioquia’s and Massachusetts General Hospital’s IRB and institutional guidelines. Experimental data is available upon request, subject to Massachusetts General Hospital and Schepens Eye Research Institute of Mass Eye and Ear institutional guidelines. Material requests and data requests will be considered based on a proposal review, completion of a material transfer agreement and/or a data use agreement, and in accordance with the Massachusetts General Hospital and Schepens Eye Research Institute of Mass Eye and Ear institutional guidelines. Please submit requests for participant-related clinical, genetic, and imaging data and samples to Y.T.Q. (yquiroz@mgh.harvard.edu) and requests for experimental data, DNA and single-cell RNA sequencing data, and antibodies to J.F.A.-V. (joseph_arboleda@meei.harvard.edu).